Subcellular systems follow Onsager reciprocity

Introduction

The mechanistic dogma populates the cell by discrete molecular machines that perform strictly defined roles. Stochastic thermodynamics was leveraged to model realistically single proteins by accounting for random thermal fluctuations at the microscopic level (e.g., refs. 1,2; discussed extensively in ref. 3). However, combining the molecular mechanisms analyzed by this methodology into a macroscopic description of the cell as an integral system is impractical. Alternatively, the cell can be viewed as an ever-changing system consisting of interacting flows that replace constantly the cell’s ingredients yet preserve its overall architecture. The interdependence between the flows is more amenable to a wholistic view of the cell rather than its perception as a grouping of discrete machines. The former premise was invoked to extract interdependence among subcellular systems from proteomic data4, and to account for the role of energy flows in the regulation of cell function5, or material flows in shaping the cytoskeleton6. Theoretical studies addressed the generation of mutual information7 and the conferral of feedback8 between coupled flows in biological systems.

The emphasis on dynamics lends itself to the implementation of thermodynamics, which, aptly, is concerned with the flow of energy. Further, thermodynamics can reduce the challenging complexity of the cell by generalizing its innumerable microstates into macrostates9. Biological systems are considered to be in nonequilibrium steady-state and harbor entropy-producing irreversible dissipative processes that are essential for the emergence and stability of their structure10. Subcellular processes function out of equilibrium, as exemplified by intracellular signal transduction11, molecular motor activity12,13, and the cell cycle14, among others.

One of the early theoretical advances in nonequilibrium thermodynamics was the realization that reciprocal relations observed, among others, between an electric current and a heat flow15, are not coincidental. The reciprocity rests on the time reversibility of the equations of motion (also referred to as detailed balance), which is assumed to hold at the microscopic scale16, as first shown by Onsager17,18. Close to equilibrium, the systems’ generalized forces (X)i and generalized flows (J)i, are assumed to be directly proportional to each other, i.e., conjugated linearly:

where ({L}_{{rm{ij}}}) are phenomenological transport coefficients. By analogy to Kirchhoff’s current law, the flows are equivalent to the electrical current, the forces to voltage gradients, and the coefficients to conductivity9. The reciprocity between the flows requires that the matrix of transport coefficients is symmetric and positive semi-definite, i.e.,: ({L}_{{ij}}={L}_{{ji}}left(i,j=1,ldots ,nright)) and ({rm{d}}{rm{e}}t([{L}_{i,j}])ge 0(i,j=1,2,ldots ,n))16, respectively. Onsager’s formulation, which is essentially reductionist, assumes an instantaneous response between conjugated flows17,18; time-dependence and, therefore, causality, can be introduced by rendering the state variables time-dependent19. The occurrence of reciprocal relationships was demonstrated among numerous artificial flows of inert materials20. Reciprocity was validated on both the theoretical values of the transport coefficients and the experimentally measured phenomenological coefficients21.

The restriction on Onsager reciprocity to the linear regime and the requirement to fulfill microscopic, detailed balance preclude its applicability to live systems, which do not necessarily function under these conditions22. Nevertheless, Onsager reciprocity realistically modeled membrane transport23. Moreover, the aqueous environment of the cell is thought to dampen molecular dynamics to the linear regime24, potentially extending reciprocity further from equilibrium. The generalized version of Onsager reciprocity goes beyond the linear regime and is not bound by microscopic detailed balance25,26,27. Although previous studies tested reciprocity only among directly conjugated flows, the theory does not exclude indirect reciprocity.

The applicability of Onsager reciprocity to the modeling of biological processes had been questioned also because the latter had been thought to be far from equilibrium. However, these processes consist of multiple reactions, each of which can be assumed to be closely linear28. This methodology was extended to metabolic and enzymatic reactions28,29, electron transport in mitochondria30, membrane transport of water and ions31,32, and the relationship between the velocity and fuel consumption rate of a generalized molecular motor33. Similarly, a linear regime is applicable to the thermodynamics of processes at the single protein scale, including a Ca2+ flux through a Ca2+-ATPase transporter34, RNA unfolding35, and molecular motor movement along actin filaments36, under the assumption that distances and time intervals are of the same scale as the protein, i.e., that they are at the mesoscopic level. Flows at this scale, such as the Ca2+ flow and a proton counter-flow, driven by ATP hydrolysis and the proton electrochemical potential difference across the plasma membrane, respectively, are related linearly and maintain Onsager reciprocity theoretically34. Integration over all the stochastic microstates to produce the macroscopic thermodynamic variables results in a transport matrix that is not symmetric and does not conform with Onsager reciprocity37, unless the driving forces are small enough, maintaining the system in the linear regime.

As a prelude, the thermodynamic nature of a prototypical cell is defined to be consistent with the homeostasis of its structure despite the incessant replacement of its components. The current methodology differs from previous applications of thermodynamic theory to cell biology by considering published measurements of cellular processes as macroscopic thermodynamic flows and their driving forces. Onsager reciprocity is validated by calculating the ratios between the transposed transport matrix coefficients of the bacterial flagellum and ATP synthase. It is then used as a predictive tool to test if reciprocity occurs between the contractile ring and treadmilling cytoskeleton in prokaryotic binary fission and eukaryotic cytokinesis.

Results

Prototypical thermodynamic profile of the cell

A thermodynamically prototypical cell that conforms with the flow-based premise would maintain its three-dimensional structure despite the incessant replacement of its components. To characterize it temporally, if ΔT is the lifetime of the cell’s structure (e.g., between two consecutive cell divisions) and δt is the average residence of a component (a protein) in the cell’s structure, then ΔT >> δt. This prototype does not specify the fate of the outgoing structural components. They may be broken down into smaller units (e.g., amino acids or peptides) used to generate new components, and/or be removed from the cell. Although the conceptual framework presented here does not specify the molecular components of the cell, they can be assumed to consist of proteins that interact via conventional chemical bonds (covalent, ionic, etc.).

The cell’s homeostasis is assumed to be maintained by autocatalysis. It relies on the sustained transfer of matter (molecules) and energy between the cell and its environment. The proteins that maintain the cell’s structure are replaced by newly synthesized proteins at variable rates as they denature due to thermal fluctuations. The feedback mechanism is posited to be regulated by temperature, i.e., the rates of protein synthesis and replenishment are proportional to the ambient temperature. The prototypical cell is assumed to perform work on its environment and maintain gradients of osmotic pressure, ionic strength, and pH between its interior and its environment. The extent of free energy converted to work on the environment during autocatalysis can be potentially lowered by synergy between cellular components. For example, the free energy of Mg2+ bound to negatively charged RNA is lower than the free energy of the separate reactants38. Consequently, the cell may operate in the linear regime, closer to equilibrium. Under this premise, the occurrence of reciprocity is more likely than appreciated.

The structure of the cell is not stored in its memory module (e.g., nuclear DNA) as such. Rather, it is maintained by uninterrupted propagation through cell divisions. The cell stores information that specifies the amino-acid sequences of its proteins. Copying errors of the stored information during cell proliferation give rise to new protein variants. Some of them modify the structure of the cell. Those that confer higher structural stability are propagated, i.e., the prototypical cell is compatible with Darwinian evolution.

Known exceptions whereby inert materials form stable patterns are special cases of heat convection due to cyclical changes in either liquid buoyancy, or surface tension39, and chemical reactions that generate oscillating patterns due to a feedback loop between the product and reactant concentrations40. Convection patterns occur spontaneously in atmospheric or ocean circulation, albeit at scales that are far removed from cellular dimensions. Chemical oscillations were observed only artificially in the presence of bromide ions. Onsager reciprocity optimizes the feedback among conjugated flows and, therefore, their stability. As such, it is a natural fit to the cell’s postulated capability to maintain its structure though its components are under constant flux.

Validation and testing of Onsager reciprocity on experimental data

Calculating the values of the transport coefficient is straightforward if the number of flow-force data points that can be resolved from experimental results is at least as large as the dimension of the square transport matrix (n), i.e., the total number of coupled flows. Once these points are known, the transport coefficients are calculated by solving n×n linear equations. In all the cases analyzed in this study, n = 2. Symmetry of a 2×2 matrix requires equality of the transposed coefficient, i.e., using in the notation of Eq. (1), that L12/L21 = 1. This ratio does not depend on the diagonal coefficients (L11 and L22), as it is given by:

where a and b denote the two data points of each force and flow. The margins of error of the L12/L21 ratios are calculated here (Table 1) by propagating41 the measurement errors in the referenced studies of the four studied cases.

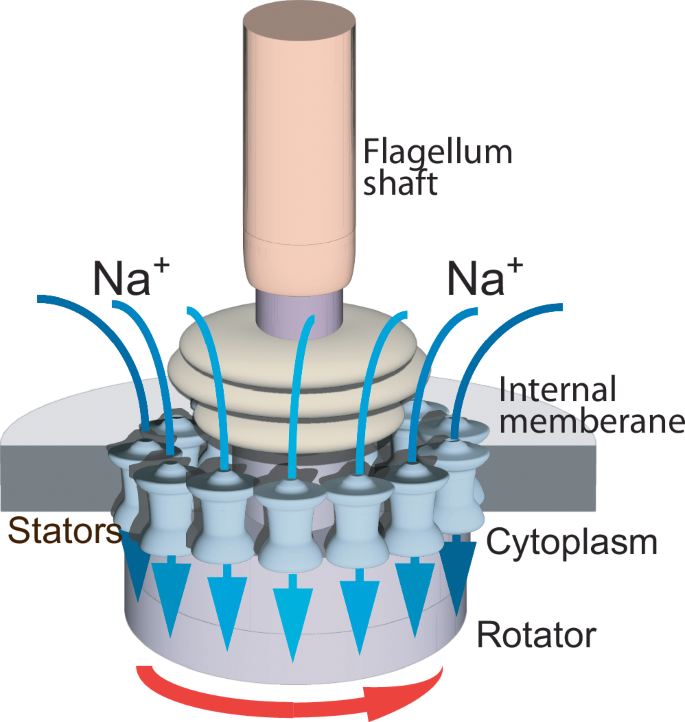

Onsager reciprocity should theoretically apply to cell biological phenomena comprehensively, provided they represent time-dependent changes cast as thermodynamic flows that are expected to affect each other either directly or indirectly. This premise was first validated on the mechanism that propels the rotation of bacterial flagellum. The rotation of the flagellum of the gram-negative marine bacterium Vibrio alginolyticus is driven by sodium ion (Na+) flux, generating a sodium-motive force (SMF)42. The two putatively conjugated thermodynamic flows are the flagellum’s rotation and the inward Na+ flux, driven by the SMF and by the Na+ gradient between the cytoplasm and the cell exterior, respectively43 (Fig. 1).

The rotation of the flagellum of the gram-negative marine bacterium Vibrio alginolyticus is driven by a proton/sodium ion (H+/Na+) inward flux through the stators (blue arrows) that span the bacterial internal membrane76. The flux generates the sodium-motive force that rotates the flagellum’s shaft (red arrow).

Conjugated thermodynamic forces and flows should be chosen so that the force is the partial derivative of the dissipation function with respect to the flow, or, equivalently, the derivative of the rate of entropy generation (multiplied by temperature in isothermal systems) with respect to a thermodynamic variable, while the flow is the time derivative of the same thermodynamic variable44. Accordingly, the SMF, (Delta {varphi }_{{Na}^{+}}), depends on the rate of entropy generation, (Delta S), as a derivative of the sodium ion number, ({n}_{{{Na}}^{+}}):

where (Delta H) is the change in enthalpy and (T) is the absolute temperature. The angular speed of the flagellum, (omega), is proportional to the time derivative

of the same variable, ({n}_{{{Na}}^{+}}):

where (eta) is the flagellar motor efficiency. The second force, the membrane potential, (Delta mu), is a function of the derivative of the free energy, (G), in respect to the net charge across the membrane, (q):

Given the relation between Gibbs free energy and the rate of entropy generation, i.e., (G=H-{TS}), the membrane potential can be expressed as a function of the rate of entropy generation derived by the net charge:

The sodium ion gradient, or flow, is simply a time derivative of the net charge:

This exposition of the thermodynamic force as a derivative of the rate of entropy generation with respect to a thermodynamic variable, and the corresponding thermodynamic flow as a time derivative of the same thermodynamic variable is repeated for all the forces and flows discussed below.

The ratio between the transposed coefficients of the flow-force transport matrix calculated from published data43 is 0.72 ± 0.24 (Table 1). The effects of all conjugated flows should be reversed once the directions of the flows themselves are reversed, because of the inherent microscopic reversibility of Onsager’s reciprocity. In accordance, the flagella of numerous bacteria rotate in both directions45. This reversal is attributed to a switch in the C-ring on the cytoplasmic side of the flagellar motor46 rather than to reversal of the direction of the sodium gradient, which would be detrimental to the maintenance of osmotic pressure and volume.

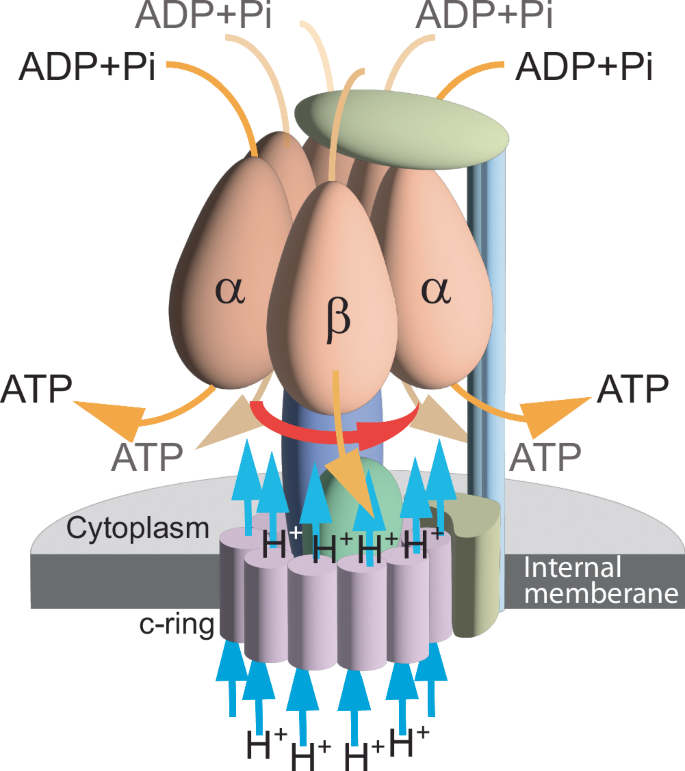

A different torque-driven mechanism underlies the function of the bacterial F0F1 ATP synthase, wherein a proton flux produces torque that drives the synthesis of ATP from ADP and Pi47 (Fig. 2). ATP synthesis and the proton flux are conjugated flows driven by the proton motive force and the energy released by ATP hydrolysis, respectively47. By analogy to the flagellar system, the proton-motive force, (Delta {varphi }_{{H}^{+}}), depends on the rate of entropy generation, ({rm{Delta }}S), as a

ATP is synthesized from ADP and Pi in the bacillus PS3 thermophilic bacterium by an inward proton flux (blue arrows) through inner membrane-spanning twin α helices (the c subunit of the synthase). The axial separation between the proton access and release channels in the c ring generates the electrostatic field in the membrane plane that drives ring rotation (red arrow) and ATP synthesis (orange arrows) by rotary catalysis performed in the 6 interspersed a and b units in the cytoplasm77.

derivative of the proton number, ({n}_{{H}^{+}}):

where (Delta {H}_{{H}^{+}}) is the change in enthalpy associated with the proton flux. ATP synthases maintain varying ratios of protons per synthesized ATP molecule, (n). The rate of ATP catalysis can be expressed, therefore, by the proton flux, i.e., a time derivative of the number of protons, ({n}_{{H}^{+}}), times (n):

The ATP synthase of Bacillus PS3 ATP, on which this analysis is based, maintains a ratio of 3.3 protons per each synthesized ATP molecule47.

The second thermodynamic force, (Delta G), the change in free energy produced by the conversion of ATP hydrolysis, can be expressed similarly to Eq. 9, although the rate of entropy generation is a derivative of the number of hydrolyzed ATP molecules, ({n}_{{ATP}}):

(Delta G) is calculated from the standard state Gibbs free energy, (Delta {G}^{0}), and ({K}_{{ATP}}), the [ATP] to [ADP](cdot)[Pi] ratio47:

where (R) is the gas constant. Given that the same proton to ATP ratio, (n), applies to ATP hydrolysis48, the proton flow is expressed as a time derivative of the number of hydrolyzed ATP molecules:

The coupling between the vectorial proton flux perpendicular to the bacterial inner membrane and the scalar ATP hydrolysis rate, which is an exception to the Curie-Prigogine principle, is permissible because of the membrane’s anisotropy49.

The calculated ratio between the transposed coefficients of the F0F1 ATPase transport matrix of 1.35 ± 0.04 (Table 1) validates the Onsager reciprocity between ATP hydrolysis and the proton flow. The inverse operation of ATP synthase, whereby ATP hydrolysis turns the motor into a proton pump, is well established50. Qualitative reciprocities between either the inward Na+ flux and flagellum rotation43, or between the proton flux and the rate of ATP synthesis, were observed experimentally47. The calculated ratios between the transposed coefficients validate these observations quantitatively and theoretically.

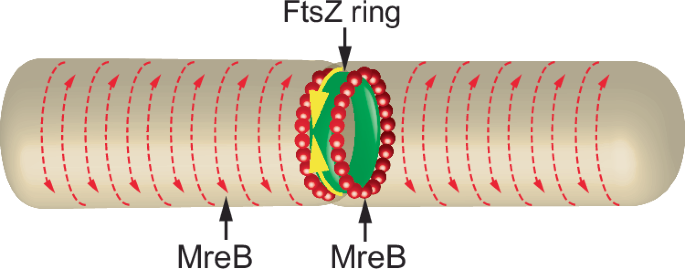

Other instances of conceivable reciprocal relationships do not appear to have been tested. A possible candidate system is bacterial cell division, where a ring consisting of treadmilling polymeric FtsZ, a tubulin homolog, constricts the cell wall, enabling separation between the dividing Escherichia coli cells51 (Fig. 3). Simultaneously, filaments of MreB, an actin homolog, are thought to participate in the elongation of the walls of nascent cells52. FtsZ and MreB bind each other directly, colocalize at the FtsZ ring, and are presumably involved in the coordination of cell division and the elongation of the separating cells53. It is intriguing, therefore, to test if the activities of the two proteins are linked causally by defining the relevant thermodynamic flows and forces and calculating the ratio between the transposed coefficients of the transport matrix. The flows are the treadmilling speed of the FtsZ ring and the speed of the circumferential motion of MreB patches along the cell wall54. The thermodynamic forces that drive each flow are GTP hydrolysis by FtsZ55, and the ATPase activity of MreB, respectively.

Separation of dividing bacteria during fission is facilitated by a contractile ring composed of polymerized FtsZ, a tubulin homolog (yellow arrows). Simultaneously, the separated bacteria elongate in a process that involves the bacterial actin homolog, MreB. Presumably, polymerizing MreB could contribute to bacterial separation by squeezing and lengthening each nascent bacterium (orange arrows).

Nucleoside triphosphate hydrolysis and the treadmilling of filamentous cytoskeleton proteins are the thermodynamic forces and flows common to both prokaryotic fission and eukaryotic cytokinesis. The expression of the force as a partial derivative of the rate of entropy generation multiplied by temperature by a thermodynamic variable, and of the flow as a time derivative of the same variable are applicable, therefore, to all the four pairs of forces and flows that are discussed below. The expression of nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) hydrolysis as a derivative of the rate of entropy generation is identical to that in Eq. 12. Because the rate of polymer treadmilling, ({J}_{{TM}}), whether of FtsZ and MreB or of their eukaryotic homologs, is directly proportional to the rate of nucleoside triphosphate hydrolysis, it can be expressed as:

where ({n}_{{NTP}}) is the number of hydrolyzed nucleoside triphosphates.

The ratio of the transposed coefficients of the transport matrix calculated from published data on the GTPase activity of E. coli binary fission FtsZ55, −0.57 ± 0.39 (Table 1) negates Onsager reciprocity between the FtsZ and MreB flows, or, speculatively, indicates an anti-reciprocal relationship between them. The lack of coordination between the movements of FtsZ and MreB is not surprising despite their mutual binding, considering the observed bidirectional circumferential rather than longitudinal movement of MreB patches56,57. This dynamic is less amenable to coupling with the FtsZ ring. Given this result, the mechanism of prokaryotic binary fission serves as a negative control case of a system that does not observe Onsager reciprocity.

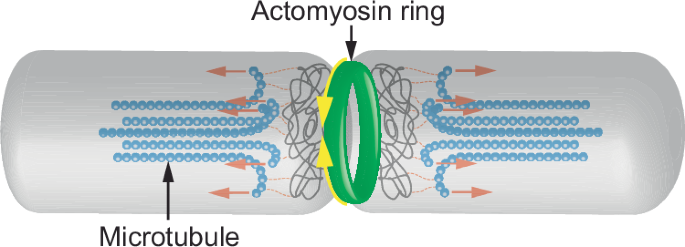

To extend the test of Onsager reciprocity to eukaryotic cytokinesis, the same process addressed in prokaryotes is tested Saccharomyces pombe (fission yeast) cytokinesis. It differs from prokaryotic binary fission in that the contractile ring is composed of actomyosin, whereas longitudinal microtubules segregate each of the two sets of chromosomes into two daughter cells58 (Fig. 4). Outward flaring and depolymerization of tubulin protofilaments following hydrolysis of microtubule-bound GTP generate mitotic poleward forces59. The constriction of the contractile ring and the shortening of the flaring and depolymerizing microtubules would hypothetically constitute reciprocal flows driven by ATP and by GTP hydrolysis, respectively. Calculation of the transposed coefficients of the transport matrix from data on the cytokinetic ring60 and on tubulin GTPase61 yields a ratio of 0.98 ± 0.94 (Table 1). Though marred by a large margin of error, this result indicates that, unlike prokaryotic fission, the shortening of longitudinal microtubules in fission yeast is likely to synergize with the contracting cytokinetic ring. Although there are no experimental data on reverse reciprocity between actomyosin ring contraction and microtubule depolymerization, the present theoretical analysis predicts that it may occur. The relatively large errors in the calculated ratios between the transposed coefficients of the transport matrices of FtsZ-MreB and microtubule-actomyosin dynamics in prokaryotic fission and eukaryotic cytokinesis, respectively, reflect the similarly large errors in the original measurements of filament movement velocities or contraction rates used in the calculations.

The roles of actin and tubulin in yeast cytokinesis differ from those of their bacterial homologs. Rather than polymeric tubulin, the contractile ring (yellow arrows) consists of polymerized actin and myosin-278. Microtubules that are aligned with the axis of the nascent yeast cells mediate the separation of the original and copied chromatin by pulling them apart. Depolymerization at the proximal tips of the microtubules is thought to generate lengthwise tension that facilitates yeast fission (red arrows).

Discussion

Although the above instances of validation or of prediction of Onsager reciprocity address the functions of molecular protein complexes, the underlying methodology is macroscopic, modeling the cell as an integral thermodynamic system. It does not capture the dynamics at the molecular level but rather of the cellular population of each subsystem, whether, for example, the bacterial flagellum, or ATP synthase. The current approach complements that of stochastic thermodynamics, which is suitable for modeling the inherent randomness at the microscopic level.

Analyzing cell dynamics as a network of reciprocally conjugated thermodynamic flows introduces causality and facilitates quantitative analysis of cellular dynamics. These methods differ fundamentally from widely published omics methodologies for investigating genetic62,63 or protein interactions64, which can identify only statistical correlations. The underlying theory is general because it does not depend on the nature of the molecular components of the cell. Once extended to other cellular subsystems, this approach may provide insight into the organizational principles of the cell as an integral system. It is conceivable that prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells harbor a substantial number of conjugated flows. Although their pervasiveness is unknown, candidates for direct and indirect instances of Onsager reciprocity can be readily hypothesized. For example, reciprocity may occur between the translocation of proteins that harbor a nuclear localization signal by importin into the nucleus and the exit of importin-bound Ran GTPase from the nucleus, driven by concentration gradients of imported cargo proteins and an opposite gradient of Ran, respectively65. Indirect reciprocal conjugation could occur between ribosomal protein synthesis and proteasomal protein degradation.

The composition of the sets of reciprocally conjugated flows may be transient, depending on the varying conditions experienced by cells. Unlike the discrete structural and functional protein assemblies of the bacterial flagellum and the F0F1 ATP synthase, within which Onsager reciprocity evidently occurs between two conjugated flows, bacterial fission, and eukaryotic cytokinesis are not self-contained and may employ multiple proteins. Considering one or more additional thermodynamic flows mediated by other proteins aside from, for example, FtsZ and MreB, would alter the composition of the transport matrix and potentially yield ratios closer to unity between the transposed coefficients of the enlarged transport matrix. While there are no known proteins that crosslink FtsZ and MreB during fission, the functional coordination between actin filaments and microtubules during cytokinesis is well documented66. This difference is a likely cause of the absence of reciprocity between FtsZ and MreB, and, conversely, for its occurrence between microtubules and actomyosin.

The ratios measured between the transposed coefficient of artificial flows of inert materials are, as one would expect, generally closer to unity20. Nevertheless, values as large as 1.46 or as small as 0.42 were reported for reciprocal electro-osmotic flows20, or for diffusive flows67, respectively. The ratios calculated here are within a similar numerical range, albeit with larger error margins that emanate from the larger measurement errors in the original experiments on live cells. The indication of previously unknown reciprocity between actomyosin contraction and tubulin depolymerization during yeast cytokinesis suggests that the symmetry of the transport matrix may predict causal relationships among other cellular flows.

The subcellular systems used here for testing Onsager reciprocity are chosen because they are amenable to analysis as putatively conjugated flows. Another essential attribute is the availability of sufficient experimental data to calculate the coefficients of the flow-force transport matrix. The same approach can be used as an unbiased test of coupling between any subcellular biological processes, whether direct or indirect, facilitating the prediction of new causal interactions between subcellular processes. If future experiments are to be more amenable to the testing of thermodynamic reciprocity, they should provide sufficient data for sampling at least as many points as the number of thermodynamic flows under consideration. Optimally, such experiments should be run on single live cells, imaging the subcellular movement of fluorescently tagged proteins, and quantifying simultaneously the rate of nucleoside hydrolysis by genetically encoded sensors. Cellular flows could be generated by perturbing steady state gradients of, for example, caged nucleosides, to elicit their driving forces. Data consisting of ratiometric rather than absolute values are difficult or impossible to use for testing the occurrence of reciprocity. The relatively large measurement errors of intracellular dynamics, such as the treadmilling of cytoskeletal proteins, may be reduced in future experiments by stimulated emission depletion imaging, which has adequate spatial and temporal resolution68. The nature of yet to be discovered reciprocal flows may differ from the currently known ones, requiring other experimental approaches.

As noted, the macroscopic methodology employed here cannot reveal molecular mechanisms or model the stochastic nature of microscopic dynamics. Studies that addressed biomolecular thermodynamics at the mesoscale level considered intermediate states (e.g., of the Ca2+-ATPase transporter37) and invoked internal variables to derive the transport coefficients theoretically. This analysis showed that the ensuing macroscopic transport coefficients are symmetric only for small driving forces. Whereas the subcellular systems addressed here are more complex and not necessarily amenable to full theoretical formulation, the corresponding experimental data afford relatively simplistic modeling. Though inferior to analysis at the mesoscopic scale, it enabled the testing of reciprocity between thermodynamic flows.

The statistical significance of the calculated transport coefficients is determined by the error margin of the experimental data, which varies widely, depending on the nature of the acquisition method, i.e., the measurement errors of intracellular movement tracked by optical imaging of fluorescently conjugated proteins were larger by approximately an order of magnitude than those of chemical or electrochemical kinetics (Table 1). These errors were propagated41 in the calculations, as shown in Table 1. All the flow-force data points used to calculate the ratios between the transposed coefficients of the transport matrix were selected from smooth and monotonous data, reducing the chance that they are anomalous results of erratic outputs. It is premature at this point to determine the overall role of thermodynamic reciprocity versus unconjugated flows in the regulation of cellular dynamics. Earlier studies claimed that biological systems are generally not coupled because reciprocity precludes amplification and oscillations, which are presumably essential for the function of biological systems69. However, this statement was eased in a subsequent letter from the same authors70. A more recent study showed that Onsager reciprocity is a special case of a more general reciprocity that holds far from equilibrium71. Certain generalized reciprocity settings enable the maximum amplification each system can accommodate, negating conflict between the two phenomena.

Responses