Surface tension enables induced pluripotent stem cell culture in commercially available hardware during spaceflight

Introduction

Stem cell research on a variety of stem cell types in low Earth orbit (LEO) has revealed multiple opportunities for understanding fundamental changes to stem cell properties and potentially harnessing these changes for biomanufacturing applications in microgravity1. Investigations into the effects of culturing stem cells in microgravity could identify novel mechanisms capable of improving biomanufacturing of cellular therapeutics on Earth, or serve as a catalyst for future large-scale, on-orbit biomanufacturing of stem cell-derived products2,3.

Experiments in simulated microgravity have shown alterations in the differentiation capacity, viability, and proliferative potential of progenitor cells derived from pluripotent stem cells4,5. Later disease modeling experiments in microgravity have indicated that the unique environment on the International Space Station (ISS) can lead to the identification of novel targets for enhancing the therapeutic benefit of heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes)6, and have demonstrated the feasibility of long-term microgravity culture of human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes7. Neural stem cells, mouse embryonic stem cells, and cardiac progenitor cells have also shown enhanced proliferative capacity in spaceflight experiments8,9,10,11. Another area of discussion is whether a sustained microgravity environment can elicit a beneficial effect on stem cell differentiation. Certain pilot data have demonstrated that microgravity may facilitate the differentiation of specialized cell types from pluripotent stem cells, such as cardiomyocytes12. However, given the limited data and difficulty of reproducing experimental results in LEO, it has yet to be confirmed if the production or differentiation of other cell types from pluripotent stem cells can also be enhanced in a microgravity environment. Indeed, there are several questions of interest regarding the impact of microgravity on fundamental stem cell properties that remain to be addressed via reproducible experiments in LEO.

Environmental stimuli and influences on mechanotransduction can alter stem cell potency, including the ability to self-renew and maintain the expression of key components in the pluripotency network13. Microgravity dramatically alters the gravitational forces experienced by cells and biological tissues, subsequently influencing mechanotransduction and downstream genetic and protein signaling pathways. The role of microgravity should be further investigated for its influence on pluripotency and differentiation capacity. For example, prior results suggest that microgravity may induce bone loss by inhibiting the differentiation capacity and cell cycle activity of osteoblasts, the mechanosensitive canonical progenitor cells that create bone14. The differentiation, morphology, and migration of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are changed in simulated microgravity, which may further be critical to osteoblast function since osteoblasts may be derived from MSCs15,16,17. Mechanistically, differentiation in microgravity could be altered by a reduction in mechanical loading, which can be “sensed” by various mechanotransduction intracellular signaling pathways found with stem cells and their derivatives18. Alternatively, these microgravity-induced alterations in differentiation capacity could be the result of epigenetic shifts in methylation patterns and chromatin structure, which have been seen with rat skeletal myoblasts under simulated microgravity19. Outside of muscle and bone-focused studies, fundamental stem cell culture conditions are reportedly altered in microgravity, such as the reduced requirement of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) for maintaining pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells20. In confirmatory studies, spaceflight was shown to maintain pluripotency and long-term survival of mouse embryonic stem cells10 while inhibiting their capacity to differentiate12. In relation to hematopoietic stem cells, DNA damage repair pathways are inhibited in multipotent human hematopoietic stem cells, which also show impaired immune cell differentiation capacity21.

Over the past 15 years, human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) have experienced a rapid rise to prominence in stem cell biology due to their near-equivalence to the more ethically-controversial embryonic stem cells and their ability to transform into multiple human somatic cell types for disease modeling, drug screening, and cell therapy22. In contrast to other adult stem cell types, the impact of spaceflight on hiPSC production, maintenance, and differentiation has not been well examined. Studies on Earth require that human somatic and pluripotent cells are produced and expanded in order to achieve critical mass for experiments related to disease modeling, drug screening, or cell therapy22. Large-scale stem cell production on Earth can be challenging due to slow growth of the cells or accumulation of genetic changes. Critical properties of fibroblast reprogramming and subsequent hiPSC production are cellular doubling time, karyotypic stability, reprogramming cellular yield, and pluripotency state (e.g., naive or primed)23. Understanding how microgravity affects these key features for both somatic cell and hiPSC proliferation will be critical to understanding whether these cells can be potentially harnessed for biomanufacturing applications in LEO.

The ability to efficiently deliver DNA plasmids into cells for temporary expression without using viral methodologies that could lead to DNA integration events remains an important area of interest for genome editing, delivery of transcription factors to direct cell fate, or reprogramming somatic cells to create hiPSCs24. However, traditional methods using lipofection, where small lipid spheres encapsulate DNA and are endocytosed within cells, remain highly variable and can be inefficient. One study previously showed increased uptake of DNA or siRNA in LEO25. Additionally, altered fluid dynamics in LEO may change the uptake of lipid particles through either prolonged lipid-cell interaction time from surface tension or through elevated autophagic function from increased membrane fluidity26,27. Enhanced lipofection or transfection in LEO could accelerate the hiPSC reprogramming and manufacturing process. This could also potentially enhance direct reprogramming technologies, whereby somatic tissues can be directly transformed from one cell type into another without transitioning through an iPSC intermediate state28. Given the natural complementarity of hiPSC and transfection technologies, as well as the potential for their enhancement in LEO, it is of significant interest to study them in tandem in space.

The implementation and use of off-the-shelf hardware in microgravity, such as commercially available 96-well plates, also further aligns research to on-Earth studies for comparison purposes and enhances experimental reproducibility. Traditionally, space-specific cell culture devices are custom-made for the microgravity environment and support both adherent and suspension culture of cells7. These devices are typically sealed, closed-system culture units that require extensive training and non-traditional methods for medium exchange, as traditional pipetting is not feasible. Their custom-built nature necessitates significant labor and meticulous design to comply with safety regulations for biomaterial culture in microgravity. The characteristics of these devices, such as material composition, gas permeability, and whether they use active or static fluid flow, vary based on the study’s requirements. Such devices have been successfully used for years as fully-enclosed, custom built cell culture dishes for microgravity cell culture, but are limited by their low-throughput (max 6-wells) and higher cost, in comparison to commercially available, off-the-shelf hardware such as 96-well plates. Commercially available culture plates, such as those made of polystyrene, offer a cost-effective alternative due to their mass production and standardized design. Polystyrene plates are commonly used for their transparency and ease of use, but they have lower gas permeability compared to some custom-built devices, which might use materials like Teflon membranes that allow better gas exchange. Commercially available plates are much cheaper and can be ordered in bulk, making them more accessible for routine use, whereas custom-built space-specific devices are expensive due to their individual specialized materials, design requirements, and labor-intensive manufacturing and assembly process. However, to use off-the-shelf, high-throughput cell culture hardware such as 96-well plates, it must be demonstrated that cell culture media can be retained in individual wells due to surface tension, and not escape due to microgravity.

Although several pilot studies have been conducted using adult and pluripotent stem cells in microgravity, the data require reproduction and standardization to identify “case scenarios” where stem cell production, differentiation, or maintenance could be enhanced in a low gravity environment in preparation for potential downstream commercial applications in LEO. With the recent acceleration of private spaceflight missions to the ISS, space is now more accessible than ever for biomedical research. We collaborated with Axiom Space, a privately funded space infrastructure developer, and BioServe Space Technologies, a ground-to-space science implementation partner, to determine the role of space microgravity on influencing hiPSC culture and transfection in 96-well plates during the weeklong Axiom Mission 2 (Ax-2) in May 2023 aboard the ISS. By using commercially available cell culture plates in our study, we demonstrate that high-throughput, off-the-shelf cell culture materials can be adapted for space biosciences research, potentially reducing costs and increasing accessibility for future studies. This approach allows for the utilization of standard laboratory equipment and protocols, making the transition to space-based research more feasible and reproducible for a broader range of scientists and institutions aiming to conduct biomedical research in space.

Results

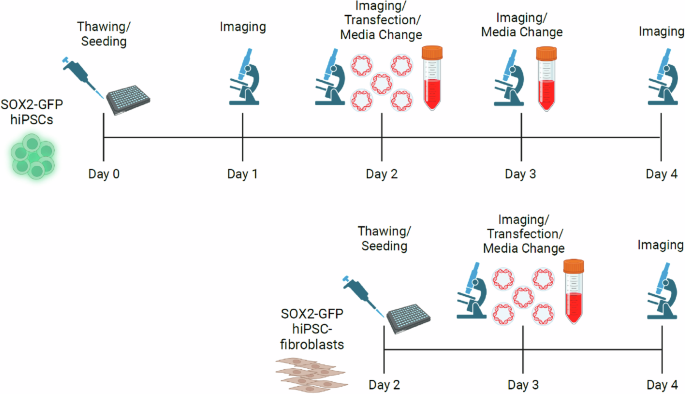

To examine the ability of hiPSCs to undergo culture and transfection in space microgravity, a custom fluorescent reporter SOX2-GFP line was used29. This hiPSC line highly expresses a SOX2-GFP fusion protein in undifferentiated hiPSCs (Supplemental Fig. 1). Similarly, SOX2-GFP hiPSCs were differentiated into fibroblasts using a chemically defined differentiation protocol (Supplemental Fig. 2). These cells are also susceptible to transfection with an RFP plasmid under standard Earth gravity. To examine cell growth and transfection efficiency during the short duration Ax-2 private spaceflight mission, an experimental timeline was devised to condense hiPSC and hiPSC-fibroblast culture, imaging, and transfection into a 5-day experiment, with the day of cell seeding considered as Day 0 (Fig. 1).

Workflow of hiPSC and hiPSC-fibroblast transfection experiment during Ax-2. Figures were created with BioRender software.

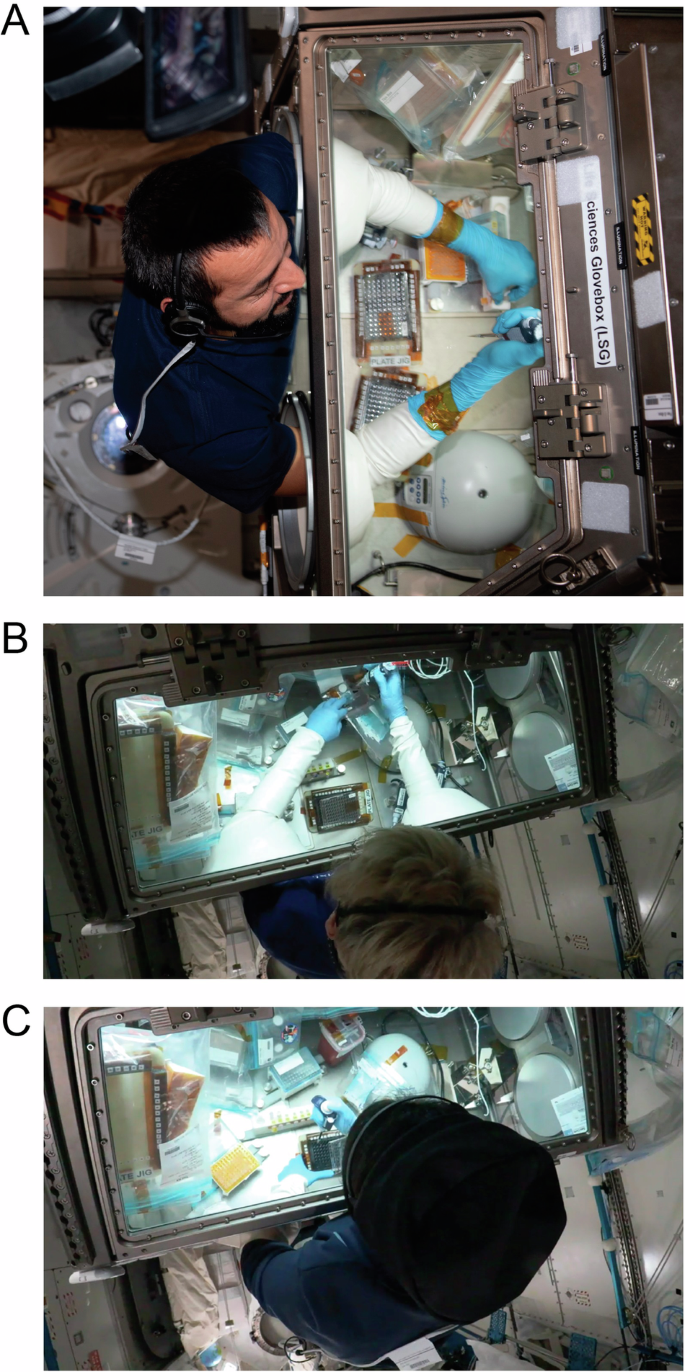

Cells were expanded and prepared on the ground and frozen into cryovials for transport into space. A SpaceX Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket containing frozen vials of hiPSCs, hiPSC-fibroblasts, and other experimental materials was launched as part of the Ax-2 mission on May 21, 2023 at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, USA. One day later, a crewed SpaceX Dragon Capsule containing all experimental materials docked with the ISS. Experimental operations began within 1 week of crew docking with the ISS. The astronaut crew on ISS were closely involved in all hands-on aspects of this experiment, including thawing and seeding cells, media exchanges, imaging, and transfection (Fig. 2). To initiate cell culture, 96-well plates harboring Matrigel extracellular matrix were thawed from -80 °C storage (Supplemental Fig. 3). Both hiPSCs and hiPSC-fibroblasts were seeded into separate plates harboring Matrigel. Importantly, the corresponding cell culture media associated with each cell type was able to remain in the commercially available, standard 96-well plate, even in the presence of microgravity, due to the surface tension forces containing the media within each well (Supplemental Fig. 4). These results indicate that commercially available cell culture hardware can facilitate cell culture even in a space microgravity environment.

Astronauts (A) Sultan Al Neyadi from the United Arab Emirates, (B) Peggy Whitson from the United States and Axiom Space, and (C) Rayyanah Barnawi from Saudi Arabia and Axiom Space conduct experimental operations on 96-well plates containing SOX2-GFP hiPSCs and SOX2-GFP hiPSC-fibroblasts in the Life Sciences Glovebox (LSG) aboard the ISS. Images courtesy of NASA and Sultan Al Neyadi.

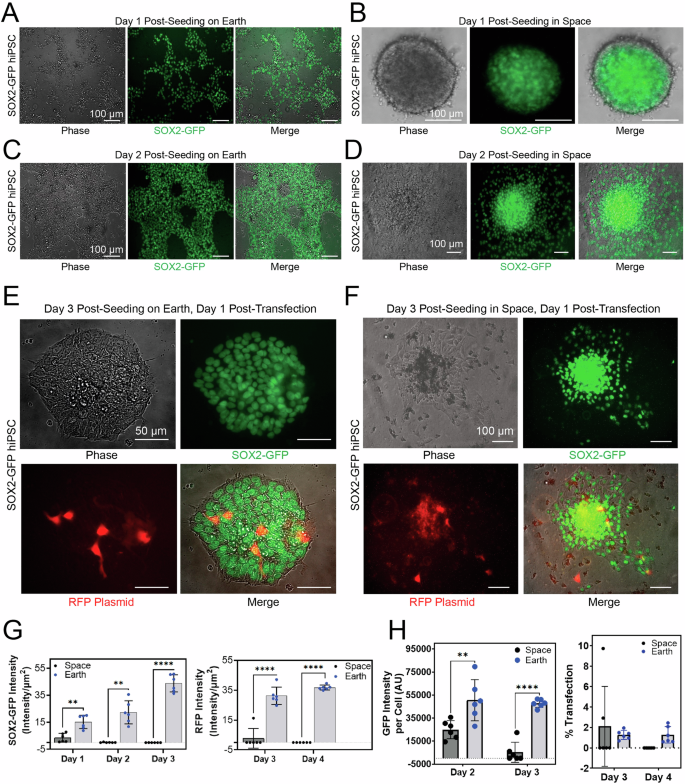

We next sought to examine growth and transfection efficiency of hiPSCs in low Earth orbit. In Earthside controls, two-dimensional (2D) SOX2-GFP hiPSCs adherent to Matrigel were grown (Fig. 3A). In space, 1 day after seeding hiPSCs, we observed the aggregation of hiPSCs into symmetrical spheroids, highly expressing the SOX2-GFP signal (Fig. 3B). These spheroids remained floating in suspension in each 96-well harboring hiPSCs (Supplemental Figs. 5, 6). At 2 days after seeding hiPSCs on Earth, cells continued to grow in 2D adhesion on Matrigel (Fig. 3C). In space, 2 days after seeding hiPSCs, we noticed that some hiPSC spheroids previously in suspension were adhering to the Matrigel (Fig. 3D). We hypothesize that this adhesion could have been facilitated by the presence of a Rho kinase inhibitor found in the cell culture media, as well as an inadvertent sudden movement of the plate harboring the seeded cells so that adhesion to the Matrigel extracellular matrix was facilitated. Fluid dynamics in space are distinct from Earth’s gravity-dominated conditions. In microgravity, the dominance of capillary action and the formation of more spherical fluid shapes due to heightened surface tension is expected, as opposed to the driving force of gravity on Earth. Nonetheless, cells continued to highly express SOX2-GFP signal, suggesting that they were maintaining their pluripotency.

A Fluorescence and phase contrast images of SOX2-GFP hiPSCs cultured in 2D on Earth. B Fluorescence and phase contrast images of hiPSCs aggregated into a spheroid 1 day after seeding hiPSCs in a 96-well plate aboard the ISS. C Fluorescence and phase contrast images of adherent hiPSCs 2 days after seeding hiPSCs in a 96-well plate on Earth. D Fluorescence and phase contrast images of adherent hiPSCs 2 days after seeding hiPSCs in a 96-well plate aboard the ISS. E Fluorescence and phase contrast images of adherent hiPSCs 3 days after seeding hiPSCs and 1 day after lipofectamine-based transfection with an RFP-expressing plasmid in a 96-well plate on Earth. F Fluorescence and phase contrast images of adherent hiPSCs 3 days after seeding hiPSCs and 1 day after lipofectamine-based transfection with an RFP-expressing plasmid in a 96-well plate aboard the ISS. The seeding day is considered as Day 0. G Quantification of SOX2-GFP signal and RFP plasmid signal in SOX2-GFP hiPSCs on Earth and in space. GFP (left) and RFP (right) signal intensity per unit area from different days of operation for SOX2-GFP hiPSCs cultured in space vs. on Earth is shown. Each dot represents an independent well of a 96-well plate. Data (n = 6) is shown as scatter dots ± std. 2-way ANOVA, α < 0.05, 95% CI. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test showed the level of significance for SOX2 signal intensity per well (left) to be P = 0.0032 (**) on Day 2, P = 0.0041 (**) on Day 3, and P < 0.0001 (****) on Day 4. For the RFP signal intensity per well (right) the level of significance was P < 0.0001 (****) for both Days 3 and 4. The seeding day is considered as Day 0. H Quantification of SOX2-GFP intensity per single cell (left) and transfection efficiency difference (right) from different days of operation for SOX2-GFP hiPSCs cultured in space and on Earth (n = 6). Single datapoints are reported as scatter dots ± std. 2-way ANOVA, 95% CI. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test showed the level of significance for pluripotency (left) to be p = 0.0011 (**) for Day 2 and P < 0.0001(****) for Day 3. The difference in percentage of cells transfected in space and on Earth (right) was non-significant.

The hiPSCs were then transfected with an RFP-expressing plasmid 2 days after seeding, and imaging was conducted 1 day after transfection to confirm uptake and expression of the RFP plasmid on Earth (Fig. 3E) and in space (Fig. 3F). RFP and GFP signals were quantified using an automated workflow to reduce bias (Supplemental Fig. 7). At days 1-3 post-seeding, cells were imaged for GFP. Quantification of pluripotency signal from adherent SOX2-GFP hiPSCs per well indicates a decrease in averaged GFP signal intensity across all wells, from day 1 to day 2, for in space samples, as opposed to the increasing signal for on Earth samples (Fig. 3G, left). At days 3 and 4 post-seeding, we also observed a significantly lower RFP signal per well after transfection, for in space samples compared to those on Earth (Fig. 3G, right). Note that these observations are only from adherent colonies of hiPSCs and are not taking the in-suspension culture into consideration. Therefore, we extended our analysis to GFP and RFP signal per single cell instead of per well (Fig. 3H), an advantage of using a genetically-modified, nuclear fluorescence reporter cell line (SOX2-GFP). At days 2 and 3 post-seeding, the SOX2-GFP signal intensity per single cell of each well was averaged across 6 wells for both conditions (Fig. 3H, left). Finally, at days 3 and 4 post-seeding, results showed a slight yet non-significant increase in transfection efficacy of SOX2-GFP hiPSCs in orbit in comparison with ground controls (Fig. 3H, right). These results suggest that hiPSCs can be grown in space microgravity in off-the-shelf 96-well plates, rapidly aggregate into spheroids, adhere to extracellular matrix in microgravity, and are amenable to lipofectamine-based transfection in LEO.

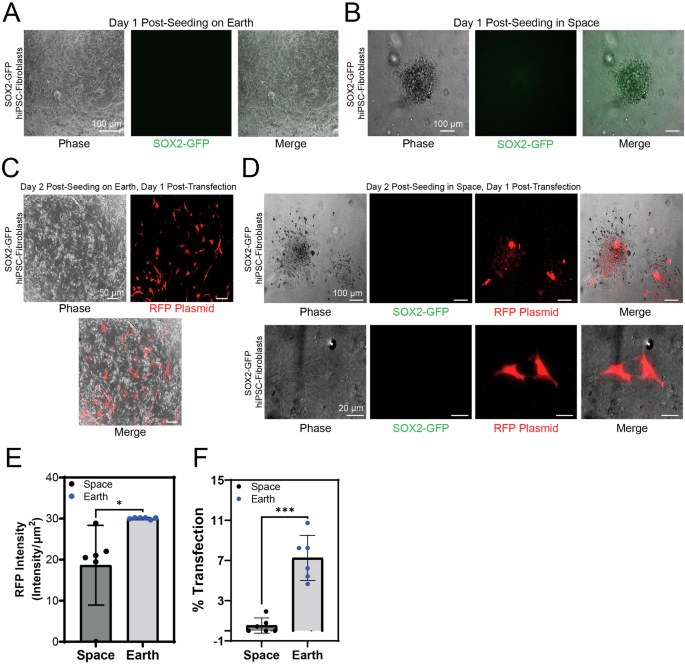

Similarly, we also examined the growth and transfection of hiPSC-derived fibroblasts aboard the ISS. Due to mission constraints, hiPSC-fibroblasts were only cultured for 2 days. The day of cell seeding was day 2. SOX2-GFP hiPSC-fibroblasts were transfected on day 3 and experiment end date was day 4 (Fig. 1). Earthside controls grew in 2D at day 1 post seeding (Fig. 4A). In space, fibroblasts were seeded in a similar fashion to hiPSCs into a 96-well plate with astronaut crew assistance. At 1 day after seeding, we observed a combination of 2D adhered hiPSC-fibroblasts and three-dimensional (3D) spheroids in suspension (Fig. 4B). The SOX2-GFP hiPSC-derived fibroblasts did not express green SOX2-GFP signal since SOX2 is most highly expressed in the undifferentiated hiPSC stage. The fibroblasts were also transfected with RFP plasmid 1 day after seeding and were imaged 1 day after transfection (2 days after seeding). Earthside control cells were susceptible to transfection with RFP plasmid (Fig. 4C). Similar to the hiPSCs, hiPSC-fibroblasts in space also expressed RFP plasmid at 1 day after lipofectamine-based transfection (Fig. 4D). Quantification of transfection signal from SOX2-GFP hiPSC-fibroblasts indicates decreased efficiency for cells transfected on orbit in comparison with ground controls (Fig. 4E, F). However, there was slight deviation from experimental protocol with experimental handling due to a loss of communication signal (LOS) with Earth, which may have affected the outcome. These results suggest that hiPSC-fibroblasts can be grown in space microgravity in off-the-shelf 96-well plates, rapidly aggregate into spheroids, adhere to extracellular matrix in microgravity, and are amenable to lipofectamine-based transfection in LEO.

Representative fluorescence images of SOX2-GFP hiPSC-fibroblasts at day 1 post-seeding (A) on Earth and (B) in space. In space, fluorescence and phase contrast images of hiPSC-fibroblasts aggregated into a spheroid 1 day after seeding in a 96-well plate aboard the ISS. (C) Representative fluorescence and phase contrast images of adherent hiPSC-fibroblasts 2 days after seeding and 1 day after lipofectamine-based transfection with an RFP-expressing plasmid in a 96-well plate on Earth and (D) in space. (E) Quantification of SOX2-GFP hiPSC-fibroblasts RFP signal on Earth and in space at day 1 post-transfection (n = 6). Intensity of RFP signal per unit area is shown. Two-tailed paired t-test showed the level of significance between Earth and space samples to be P = 0.033 (*). (F) Quantification of the difference in transfection efficacy between hiPSC-fibroblasts in space and on Earth at day 1 post-transfection (n = 6). Single datapoints are reported as scatter dots ± std. Welch’s two tailed t-test showed the significant of difference between Earth and space sample to be p = 0.0004 (***), 95% CI.

Discussion

We demonstrate the successful culture and transfection of hiPSCs and hiPSC-fibroblasts in low Earth orbit aboard the ISS. Notably, the hiPSCs and hiPSC-fibroblasts were thawed on orbit and successfully cultured for multiple days in standard, commercially available 96-well culture plates, for the first time. These standard culture plates were able to retain hiPSC and fibroblast cell culture media, even in the presence of microgravity, due to high surface tension in the relatively small well size found in 96-well culture plates. This is important to note from an experimental operations standpoint, since it demonstrates that cell culture can be conducted in LEO without the use of custom hardware, such as fully-enclosed cell culture plates that have been used in the past7. Intriguingly, on day 1 post thawing and seeding homogenously distributed SOX2-GFP hiPSCs in microgravity, we observed aggregation of hiPSCs into spheroids. This aggregation is likely facilitated by microgravity, as has been demonstrated in other cell types in both simulated and space microgravity30,31. These results show that hiPSCs can be grown as floating aggregates in microgravity. It is possible to mimic aggregation on Earth by using suspension culture techniques such as low adhesion plates or a shaker to maintain a spherical structure of cell aggregates, but these Earthside approaches introduce additional force vectors or shear stress32,33,34.

In this manuscript, we have shown that hiPSC suspension culture and spheroid formation occur naturally in space microgravity. However, we noted that on day 2 after seeding, hiPSC spheroids began adhering to the Matrigel extracellular matrix substrate added to the bottom surface of these 96-well plates. This surface adhesion was likely facilitated by the presence of Rho kinase inhibitor, and potentially by inadvertent sudden movement of the plate leading to hiPSC spheroids contacting and adhering to the matrix. The SOX2-GFP fluorescence reporter was a useful tool to qualitatively and quantitively examine hiPSC health, cell number, morphology, and pluripotency, as well as to rapidly identify hiPSC spheroids and adhered colonies during a very limited microscopy imaging time window. SOX2 is a marker of pluripotency as well as neural epithelial stem cells35,36 and could possibly reflect transition to a neural state. However, for this mission, SOX2 expression likely represents pluripotent cells given that cells were cultured for only 3 days and were maintained in hiPSC culture media. Furthermore, cell morphologies were more like pluripotent cells than neuroepithelium that is generally visualized as SOX2-positive rosette-like structures35. Additionally, SOX2-GFP hiPSCs cultured on Earth for 5 days were stained with the canonical stem cell marker, OCT4, (Supplemental Fig. 1), which indicated pluripotency of hiPSCs based on co-localization of the SOX2 and OCT4 markers. We observed less variability of SOX2-GFP signal per single cell for in space samples (Fig. 3H, left), with one possible reason being a more homogeneous and stable expression of the SOX2 gene in space, although additional data is needed to confirm this possibility. The decrease in GFP intensity per single cell on day 3 for in space samples (Fig. 3H, left), can be due to multiple reasons, few of which are cells being lifted off the surface due to fluid drag force, cell health in 96-well plates in space, or higher uptake of transfection plasmid in space resulting in more cell death compared to on-Earth samples, and hence a decreased total number of cells. We were also able to demonstrate successful lipofectamine-based transfection of an RFP plasmid into SOX2-GFP hiPSCs, which is to our knowledge, the first successful demonstration of pluripotent stem cell transfection in LEO. Our results highlight a slight yet non-significant increase in transfection efficacy of SOX2-GFP hiPSCs on orbit in comparison with ground controls (Fig. 3H, right). This lays the groundwork for future hiPSC reprogramming and genome editing experiments, which both use similar transfection approaches.

Like hiPSCs, SOX2-GFP hiPSC-fibroblasts were successfully thawed on ISS, created spheroids in suspension in the 96-well plate, and subsequently adhered to the bottom of 96-well plates coated with Matrigel in the presence of Rho kinase inhibitor. Interestingly, some adherent fibroblasts were still transfected with the plasmids, showing that this may be an efficient way to generate hiPSCs on orbit – an observation that will shape our upcoming missions attempting to create the first hiPSC lines in LEO. Notably, the SOX2-GFP signal was not expressed in these differentiated fibroblasts since SOX2 is a marker of undifferentiated hiPSCs. In future hiPSC reprogramming experiments, we will examine the re-initiation of SOX2-GFP expression as a sign of successful hiPSC production. Due to time restrictions during mission operations, we were only able to grow hiPSC-fibroblasts for 3 days in active culture. However, on day 1 after seeding, we were able to confirm hiPSC-fibroblast survival, 3D aggregation, and adhesion to Matrigel. This combinatorial 2D/3D culture was likely facilitated by the presence of extracellular matrix provided by Matrigel, and we anticipate that without Matrigel, the fibroblasts and hiPSCs would exclusively form spheroids in space microgravity. On day 1 after thawing and seeding, we transfected the fibroblasts with an RFP plasmid using lipofectamine. On day 2 after transfection, we were able to confirm RFP signal, demonstrating successful fibroblast transfection in LEO.

Despite the short, 5-day time span of this experiment, we were able to demonstrate successful 2D and 3D culture and lipofectamine-based transfection of both hiPSCs and hiPSC-fibroblasts. This experiment also successfully established the groundwork and feasibility of more complex, multi-step, long-term cell culture approaches, given the substantial technical challenges generally associated with conducting cell culture in space. We plan on conducting a full, month-long hiPSC reprogramming experiment in space. This study also demonstrates the feasibility of culturing and transfecting multiple cell types in cost-effective, off-the-shelf cell culture hardware in LEO. Commercially available 96-well culture plates, such as those used here, offer a cost-effective alternative to custom, microgravity-optimized hardware due to their mass production and standardized design. Importantly, we demonstrate that these 96-well plates can retain cell culture media by surface tension within individual wells, counteracting the effects of microgravity. Commercially available plates are much cheaper and can be ordered in bulk, making them more accessible for routine use, whereas custom-built, space-specific devices are expensive due to their individual specialized materials, design requirements, and labor-intensive manufacturing and assembly process. Future experiments will move towards incorporating automation to reduce hands-on astronaut time for experimental manipulations. Additionally, the feasibility of higher throughput experiments will be examined, to promote experimental reproducibility and improve data yield for greater statistical power, which is a limitation of this study and prior space biology studies. Ultimately, we believe that the accelerating frequency of private spaceflights to the ISS and LEO will lead to an exponential growth in stem cell-related experimental data that will inform future in-space biomanufacturing applications.

Methods

Experimental Verification Test (EVT)

To assure the safety of our biomedical research activities on the ISS, BioServe Space Technologies in Colorado, USA facilitated a ground test of Ax-2 experimental material and equipment, conducted at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The EVT included a complete run through of the experimental plan for Ax-2, using the exact equipment and material that was to be used on the ISS. Discussions regarding experiments included precise timings for each event that involved astronaut crew time, the exact equipment required for completing the experiment on orbit, tips for cell culture work on Earth that could be implemented in space, and how the BioServe team would communicate experimental protocols to the astronauts.

hiPSC culture

The SOX2-GFP hiPSC line derived from Coriell and the Allen Institute for Cell Science was maintained on Earth at 37 °C in a Forma Steri-Cycle CO2 incubator (ThermoFisher) with 5% CO2. Cells were routinely maintained in mTeSR Plus medium (STEMCELL Technologies) on a 1:200 dilution (v/v) of 50 μg/mL Matrigel (Corning) and passaged every 3–4 days using 0.5 mM EDTA in PBS. hiPSCs were replenished every other day with 2 mL mTeSR Plus medium and routinely tested for mycoplasma using a MycoAlert Plus Kit (Lonza).

Freezing hiPSCs

hiPSC frozen stocks were prepared on ground from cultures for in-flight experiments. Cells were lifted using 0.5 mM EDTA in PBS, centrifuged at 400 rcf for 5 min, and counted to determine a total number of cells in culture. hiPSCs were then resuspended in CryoStor CS10 solution (STEMCELL Technologies) and transferred to cryogenic vials pre-wrapped in Velcro (ThermoFisher) at a ratio of 500,000 cells in 0.5 mL CryoStor per vial. Cryogenic vials were then transferred into a Styrofoam freezing vessel for 24 h at -80 °C before being stored in a liquid nitrogen cryotank indefinitely prior to spaceflight. Cells were counted and stored according to optimized values from on-Earth preliminary testing of hiPSC transfection.

hiPSC-fibroblast differentiation

hiPSC-fibroblasts were produced from the SOX2-GFP hiPSC culture following a chemically defined protocol as published previously37 with variation of CHIR99021 GSK3-beta inhibitor (Cayman Chemical). Concentrations of CHIR99021 ranging from 8 – 12 µM were added to RPMI 1640 (ThermoFisher) and B27 minus insulin (ThermoFisher) medium for days 0–2 on hiPSCs. From days 2–3, the medium was substituted to just RPMI 1640 and B27 minus insulin, with the addition of 2 µM Wnt-C59 (ThermoFisher) at day 3 for days 3–5. EGM2 media (Lonza) containing 25 ng/mL recombinant human FGF-basic (Peprotech) was then added and changed every 2 days until day 12.

Freezing hiPSC-fibroblasts

hiPSC-fibroblast frozen stocks were prepared on ground from cultures post day 12 of differentiation for in-flight experiments. Cells were lifted using TrypLE Express, centrifuged at 400 rcf for 5 min, and counted to determine a total number of cells in culture. hiPSC-fibroblasts were then resuspended in CryoStor CS10 solution and transferred to cryogenic vials pre-wrapped in Velcro (ThermoFisher) at a ratio of 1,000,000 cells in 0.5 mL CryoStor per vial. Cryogenic vials were then transferred into a Styrofoam freezing vessel for 24 h at -80 °C before being stored in a liquid nitrogen cryotank indefinitely prior to spaceflight. Cells were counted and stored according to optimized values from on-Earth preliminary testing of hiPSC-fibroblast transfection.

Launch kit preparation

Frozen SOX2-GFP hiPSC and hiPSC-fibroblast cryovials along with various media and transfection components were shipped from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center to Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, USA. A total of four cell vials, two for each cell type, were stored and launched at -80 °C. SOX2-GFP-hiPSCs were pre-counted and frozen at 500,000 cells per vial, and SOX2-GFP-hiPSC-Fibroblasts were pre-counted and frozen at one million cells per vial, to streamline astronauts’ operations. One vial per cell type was allocated to seed six wells of two 96-well plates, a total of 12 wells, and the other vial was used as a backup in case the first vial perished due to temperature fluctuations. The 96-well plates utilized in this study were Nunc™ MicroWell™ 96-well flat-bottom black plates (ThermoFisher Scientific, cat. no. 165305), designed for adherent cell culture. At KSC, 3 days prior to launch, imaging-optimized black clear bottom 96-well plates were coated with a 1:200 dilution (v/v) of 50 μg/mL Matrigel in the first 6 wells per plate, with 2 plates per cell type, and stored at -80 °C in vented Bitran bags prior to launch gear turnover. Two frozen cryogenic vials, pre-wrapped in Velcro for stationary stability aboard the ISS, per cell type, were also stored at -80 °C in Bitran bags prior to launch. Syringes and microtubes including the media for seeding, transfection, and media changes per cell type were filled to pre-approved volumes and stored at 4 °C in individual Bitran bags per experiment event prior to launch. Each syringe was filled using a closed-system plunger tool to ensure sterility. All packaged Bitran bags were then transferred into larger Bitran bags that included additional standard lab tools (pipettes, plate holders, pipette tips) as well as tape and Velcro for use in microgravity and turned over to NASA for rocket stowage. The larger Bitran bags accounted for NASA’s 2 level containment of biomatter regulations.

hiPSC and hiPSC-fibroblast seeding on orbit

In the Life Sciences Glovebox (LSG) on orbit, hiPSCs and hiPSC-fibroblasts were seeded at roughly 41,000 and 83,000 cells per well, respectively, onto the black 96-well Matrigel plates. hiPSCs were seeded in 6 wells each on 2 plates, S/N1 and S/N2, from 1 vial of frozen cells thawed in mTeSR Plus medium containing 1% Antibiotic Antimycotic (ThermoFisher) and 10 μM Rho kinase inhibitor (Reprocell). We refer to this media as hiPSC feeding medium. hiPSC-fibroblasts were seeded in 6 wells each on 1 plate, S/N4, from 1 vial of frozen cells thawed in Advanced DMEM/F-12 (ThermoFisher) containing 1% Antibiotic Antimycotic, 20% Fetal Bovine Serum (ThermoFisher), 25 ng/mL recombinant human FGF-basic, and 10 μM Rho kinase inhibitor. We refer to this media as the hiPSC-fibroblast feeding medium. Both culture medias were pre-mixed and loaded into 3 mL syringes at KSC, prior to launch. Matrigel plates were initially removed from -80 °C stowage on orbit and placed in the Space Automated Bioproduct Lab (SABL) at 37 °C with 5% CO2 1 day prior to seeding. On day 0, the proper pre-packaged kit for seeding, including the Matrigel plates, were added to the LSG. Within the LSG, cryogenic vials were thawed using a thaw pouch heated to 43 °C and 1 mL of each cell type-specific media was added per vial using the pre-filled syringes to deactivate the CryoStor. hiPSC feeding medium and hiPSC-fibroblast feeding medium were added to frozen SOX2-GFP hiPSCs and SOX2-GFP hiPSC-fibroblasts, respectively. All vials were centrifuged at 400 rcf for 5 min and 1.2 mL of supernatant was extracted from each vial. Using the pre-filled syringes, 1.2 mL of each media type was added back to the respective vials and followed by an additional centrifugation round. The supernatant from each vial was once again removed at 1.2 mL, and a final addition of 1 mL of each media type was added to the respective vials. Each cell type was then seeded at 100 μL from the single cell suspension in their respective vials into each of the 6 wells per plate. A Breathe-Easy sealing film (Sigma-Aldrich) was applied under the lid of each plate as NASA’s Biosafety 2 level containment measure. Seeded plates were then transferred from the LSG back to SABL for incubation.

hiPSC and hiPSC-fibroblast transfection

Due to the fluidity of operation schedules and crew time constraints during spaceflight, hiPSCs were transfected on day 2 post-seeding, while hiPSC-fibroblasts were transfected on day 1 post-seeding on orbit. For both cell types, the first 3 wells on each plate received a full transfection media exchange of 100 μL, while 50 μL of transfection media was added to the last 3 wells to bring each total volume to 150 μL. This approach was selected to preserve some spheroids that formed, such that not all spheroids would be washed away during a full media change for transfection. The plates were transferred to and from SABL pre- and post-session in the LSG and a new Breathe-Easy film was applied to each plate once the transfection media additions were completed. To prepare the transfection media for the first 3 wells on each plate, using the pre-filled tubes, 14 μL Lipofectamine Stem Transfection Reagent (ThermoFisher) and 7 μL MISSION pLKO 1-puro-CMV-TagRFP Positive Control Plasmid DNA were added to 700 μL Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium (ThermoFisher) and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. For the last 3 wells on each plate, the transfection media instead contained 28 μL Lipofectamine Stem Transfection Reagent and 14 μL MISSION pLKO 1-puro-CMV-TagRFP Positive Control Plasmid DNA in 700 μL Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium, to maintain the same concentration of transfection cocktail in all wells.

hiPSC media exchange

hiPSCs received a media exchange on day 2 following transfection on orbit in LSG. The first 3 wells of the plate S/N1 received a full media exchange of 100 μL mTeSR Plus medium and 1% Antibiotic Antimycotic, while the last 3 wells received half a media exchange of 75 μL. The plate was transferred to and from SABL pre- and post-session in the LSG and a new Breathe-Easy film was applied following the media exchange.

hiPSC immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry staining was performed by fixing cells in PBS containing 4% (v/v) paraformaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized in PBS containing 0.2% (v/v) Triton X-100, followed by blocking in PBS containing 3% (w/v) Bovine Serum Albumin. Samples were incubated with a primary antibody to OCT4 (Stemgent) with 1:100 (v/v) dilution in block solution, followed by a secondary antibody and imaged using a Keyence scope (BZ-X810; Keyence).

hiPSC and hiPSC-fibroblast imaging

Both hiPSC plates, S/N1 and S/N2, were imaged day 1 post-seeding, while only 1 hiPSC plate, S/N1, continued to be imaged on day 2, 3, and 4 due to mission timeline restrictions. The hiPSC-fibroblast plate, S/N4, was imaged on day 1 and 2 post-seeding. All plates were imaged on orbit on the Keyence Research Microscope Testbed (KERMIT), harboring a BZ-X810 All-in-One Fluorescence Microscope (Keyence), at 10X and 20X objectives and phase-contrast, GFP, and RFP channels per timepoint. Each plate was transferred to and from SABL pre- and post-imaging session. The existing Breathe-Easy film on each plate remained in place for each imaging session.

Data analysis

The data in this study is presented as qualitative and quantitative intensity variations of GFP and RFP fluorescent signals from hiPSCs and hiPSC-fibroblasts before and after transfection. All fluorescent signal acquired from both channels are normalized based on exposure time, using the images of day 1 post-seeding, as a reference. The final data is reported as fluorescent intensity per μm2 of surface area. To measure cell pluripotency, normalized GFP intensity is quantified per single cell of SOX2-GFP hiPSCs and is compared between groups. Quantified data is reported as the mean ± standard deviation (STD). Statistical analysis was carried out using the non-parametric method of Kruskal-Wallis (i.e., one-way ANOVA) and Welch’s two tailed t-test with a confidence interval of 95% (α < 0.05 versus control).

Image consent

Authors have obtained written consent to publish the details, images, and videos pertaining to in-space astronaut operations, such as those presented in Fig. 2.

Responses