Sustainable intensification of agriculture: the foundation for universal food security

Introduction

Food security is a human right, embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (1966). The United Nations (UN) Rome Declaration on Global Food Security (1996) provided a comprehensive and robust definition of food security that focused on access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food for all1. This definition inspired the concept of universal food security: healthy diets for all, from sustainable food systems2.

The global food system is failing to deliver universal food security. The UN reported that ~735 million (one in 11) people in 2023 were hungry—as measured by energy (calorie) availability3. Broader indicators of food deprivation, including the prevalence of moderate to severe food insecurity, access to nutritious diets, and incidence of micronutrient deficiency, suggest that around three billion people are unable to meet their nutrition needs3. COVID-19 disruptions, climate change, and conflict have adversely affected food security4. The Ukraine-Russia conflict has highlighted the vulnerability of food supply chains and the impacts of crises on the poorest and marginalized in society5.

With the current state and trajectories of hunger, malnutrition, and dietary change, coupled with land degradation, water resource depletion, biodiversity loss, and climate change, the gap between ambition and reality is steadily growing. The quest for universal food security has stalled. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2 will not be achieved. And this has dire consequences for peace, prosperity, and the environment. In this paper, sustainable intensification (SI) of agriculture is presented as an essential but not sufficient foundation for achieving universal food security.

Green revolutions in Asia and Africa: genesis of SI

In response to predictions of famine in the 1950s and 1960s, governments, international development agencies, and philanthropies turned to new technology (high-yielding varieties and inorganic fertilizer), infrastructure investment (roads and irrigation), and supportive policies (input subsidies, farm credit, and market support) to boost agricultural productivity6. With a major focus on staple crops in Asia, this combination of investments became known as the Green Revolution. The Asian Green Revolution represents one of humanity’s greatest achievements and provided the foundation for reductions in poverty and hunger, as well as broad export-led economic growth across the region7. In addition, improved agricultural productivity slowed land conversion, with one study showing that 18–27 million ha of pastures and forests were saved through the Green Revolution8.

Efforts to implement the same approach to productivity improvement in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have failed for several reasons2. First, 96% of arable land in SSA is rainfed, and much of it is depleted of nutrients9. Second, unlike in Asia, where rice and wheat contributed almost all of the staple calories, agriculture in SSA was diverse and some important staple foods, including root and tuber crops, received less research. In addition, structural adjustment policies during the 1980s led to the dismantling of government support that was so critical in Asia. Poor infrastructure, urban bias, and poor governance and conflict further curtailed efforts to intensify agriculture in SSA through the Green Revolution approach2.

In 2004, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan recognized the vulnerability of African smallholder farmers to climate shocks and declining soil fertility, while acknowledging that the scientific breakthroughs obtained in Asia could not be directly applied to Africa10. Annan drew on the work of the UN Millennium Project Hunger Task Force, and called for a different kind of Green Revolution—a more holistic approach that would include small-scale irrigation, improvements in soil health, and complementary investments in infrastructure and social safety nets11. Annan described this new approach as a “uniquely African Green Revolution,” and it led to greater visibility and investment in African agriculture by governments, donor agencies, and philanthropic agencies12.

The Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), drawing on decades of research by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) and national partners, has championed greater investment in research and development for the major staple crops. The Comprehensive African Agricultural Development Program (CAADP), established by the African Union, has encouraged African governments to invest more in agriculture-led development. The African Development Bank has prioritized agriculture through its Feed Africa initiative.

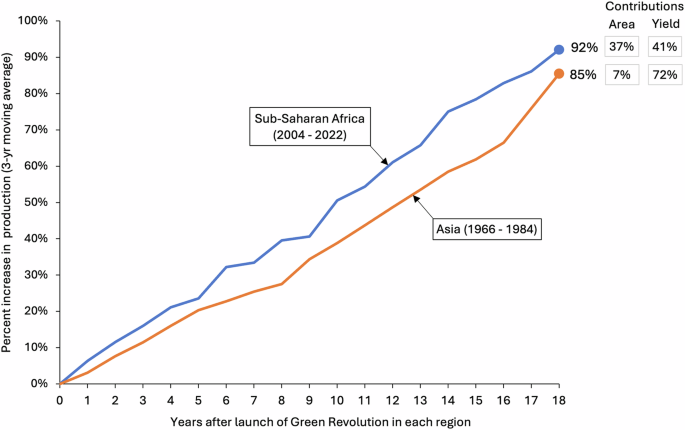

The impact of these and related investments in agricultural productivity improvement in SSA is now apparent in the case of cereal crops. A comparison of SSA and Asia reveals surprising parallels (Fig. 1). Taking a baseline of 2004—the year of Annan’s call for a “uniquely African Green Revolution”—cereal crop production in SSA had increased by 92 percent by 2022. Taking the baseline for Asia’s Green Revolution as 1966—the year the “miracle rice” variety IR8 was released in the Philippines—cereal production across Asia increased by 85 percent over the equivalent period (18 years). While Asia’s increase came almost entirely through higher yield per hectare (72% yield increase, 7% area expansion), the cereal crop production increases in SSA came in almost equal measure from yield increase (41 percent) and area expansion (37 percent).

Each data point on the figure reflects the three-year moving average ending in the designated year. Figure 1 was prepared using Microsoft Excel. Source: FAOSTAT. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

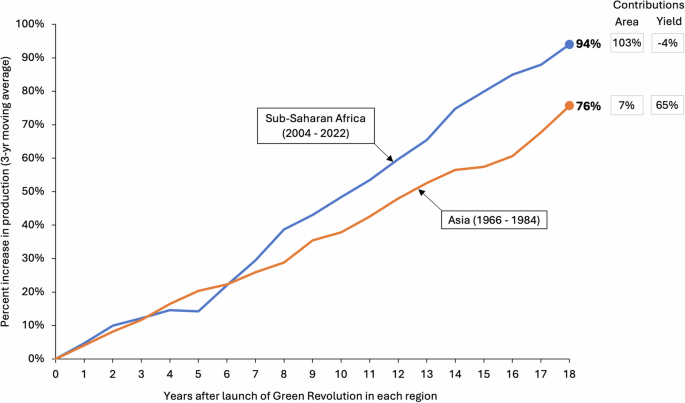

In SSA, root and tuber crops, such as cassava, yams, and sweet potatoes, are important staples. Between 2004 and 2022, production of root and tuber crops in SSA increased by 94%, but entirely through crop area expansion (Fig. 2). In Asia, as in the case of cereals, production gains came mainly through yield increases on existing agricultural land. Thus, the Green Revolution in Asia enabled the intensification of cereals and root and tuber crops, while the African Green Revolution led to both intensification and extensification for cereals but principally extensification for root and tuber crops.

Each data point on the figure reflects the three-year moving average ending in the designated year. Figure 2 was prepared using Microsoft Excel. Source: FAOSTAT. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

Conversion of land to agriculture has been an essential component of human civilization and development for millennia. Land use change, however, has caused land degradation, biodiversity loss, and GHG emissions13. In Asia, agricultural intensification is now the norm, and the scope for conversion of forest land has slowed, though it continues in some pockets, notably in Indonesia associated with palm oil production14. There have been claims of substantial progress toward SI over the past two decades, including in Africa15. However, there is a less optimistic view that SI remains more of a vision than a short-term solution16.

Green Revolution approaches will likely remain the best strategy for improving crop productivity, though with increased emphasis on traditional crops such as millets, sorghum, and cassava17. The challenge is how to intensify crop production more sustainably. Increased use of inorganic fertilizer, incorporating improved agronomic efficiency and integrated soil fertility management principles will be needed to boost the productivity of major staples and non-traditional cereal crops18. Incorporation of trees will likely play an important role in contributing to soil and land rehabilitation, carbon sequestration, and biodiversity19. Further intensification of cropland will also require investments that build resilience to climate change, including investments in irrigation infrastructure, drought-tolerant varieties, locally appropriate information services, and crop insurance17.

The case for SI

SI aims to increase agricultural production while minimizing collateral environmental damage. The concept was initially characterized and interpreted as “regenerative, low‐input agriculture, founded on full farmer participation in all stages of development and extension” supported by “local processes of innovation and adaptation” to reduce dependency on external inputs20. However, emphasizing “low-input agriculture” ignores two fundamentals of the global food system: global food demand is increasing21, and farming is not a closed system22. As food exits the farm environment, increasingly to meet the demand of urban consumers, the nutrients for maintaining productivity must be replenished.

Most academics and development agencies now accept an alternative definition of SI as a strategy for increasing production with more efficient resource use and reduced environmental damage23,24. SI aims to avoid the cultivation of additional land and halt the loss of natural ecosystems and associated environmental services. That does not mean that every field and farm should intensify. Instead, we should see SI as a transformation process in the aggregate, comprising five complementary interventions undertaken in context25:

-

1.

Increasing farm output through increased input use and improved input use efficiency26.

-

2.

Maintaining farm output with a reduced environmental impact, through improved input use efficiency27.

-

3.

Restoring abandoned or neglected arable land, through the strategic use of critical mixed cropping approaches such as agroforestry and strategic use of inorganic fertilizers28.

-

4.

Reducing farm output or exiting crop production altogether by shifting to agricultural systems with less environmental impact or returning land to natural ecosystems, including greater use of indigenous tree systems29.

-

5.

Protecting and valuing natural ecosystems for their environmental services, including carbon storage, biodiversity conservation, and watershed management30.

The net result of applying this portfolio of interventions at global, regional, and national levels is increased food availability with a reduced environmental footprint. It is necessary to build on relevant Green Revolution investments, while drawing on knowledge and experience from mixed farming systems, agroecology, as well as organic and conservation agriculture systems31. Local context and access to markets should drive the extent of external input use15.

Building on the successes and recognizing the limitations of the green revolutions in Asia and SSA, this pragmatic approach to SI implies that additional external inputs—applied strategically through the first three interventions above—will be required to meet anticipated consumer demand. However, this more holistic approach to SI calls for concurrent deintensification of agriculture in settings where resources and inputs are currently being used inefficiently. As a result, by applying this nuanced, contextual approach to SI, we can reduce and even eliminate the need to expand the agricultural frontier through deforestation.

Beyond SI

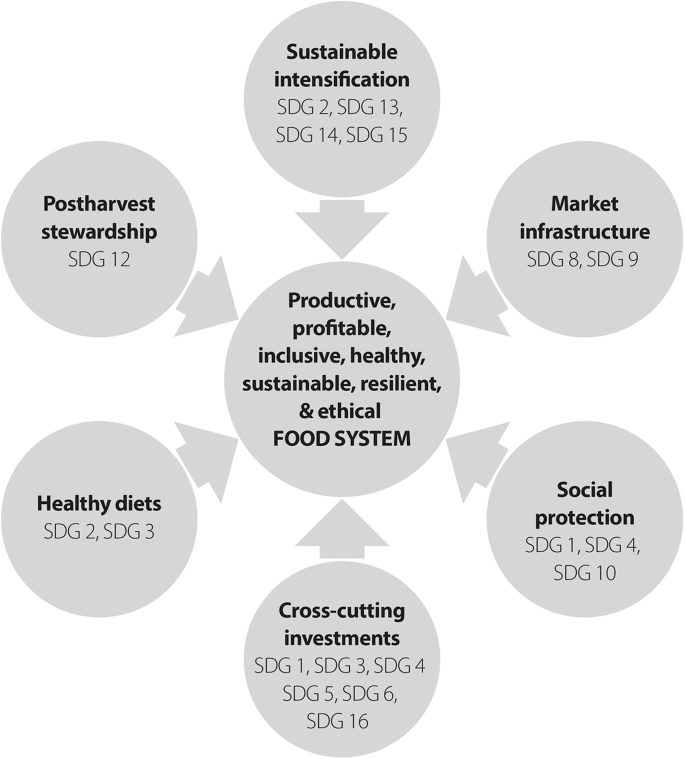

Producing enough food to meet the nutritional needs of 10 billion consumers by 2050 is the cornerstone of universal food security. But investing in SI is just one component of a broader set of investments needed to transform the food system and align with the SDGs (Fig. 3). Complementing SI are four other investment areas2:

Figure 3 was prepared using Adobe Illustrator. (Denning, 2023, reproduced with permission of Columbia University Press).

Market Infrastructure: Food availability must be coupled with food access. Physical infrastructure investment— in roads (and other transport conduits), electrification, and information technology—is necessary for connecting producers and consumers32. Supportive policy environments that enable movement of commodities within and between countries are necessary complementary investments.

Postharvest Stewardship: One-third of all food produced is not consumed33. Postharvest losses and waste represent missed opportunities to improve profits for farmers and reduce the cost of food to consumers. In addition, food losses and waste embody the resources (land, water, fertilizer, energy, and labor) used and the environmental costs of producing this unconsumed food. Establishing SDG 12.3 was a significant step toward improving postharvest stewardship34.

Healthy Diets: Evidence-based policies and interventions are shown to cut undernutrition and show promise in reversing overweight, obesity, and diet-related diseases35. For the undernourished, this means filling in the nutritional gaps without overshooting the requirements with unhealthy outcomes. Turning science into practice for better human nutrition is difficult and requires investment at multiple levels by multiple actors36.

Social Protection: When people are unable to provide for themselves, society can step in to protect and support the most vulnerable through systems, policies, and programs that are collectively described as social protection37. In a food and nutrition context, social protection helps meet the needs of people who face various forms of malnutrition as a result of conflict, natural disasters, poor health, or extreme poverty38.

There are additional cross-sector investments that are not unique to the food system but contribute to better food security outcomes. These include interventions to improve water and sanitation, improved governance, women’s empowerment, and broader improvements in education and health2.

Conclusion

The green revolutions in Asia and SSA have made major contributions to staple food supply and food security in both regions. In Asia, this increase came primarily through intensification, while, more recently, in SSA, increased crop production has come from intensification and extensification. In both settings, there are significant environmental costs. The current state and trends in hunger, malnutrition, and dietary change clearly show that we will not meet SDG 2 by 2030.

A more nuanced and rights-based approach to food security is proposed. The concept of universal food security describes a world where every person enjoys a healthy diet derived from sustainable food systems. Building on the progress and lessons from the green revolutions in Asia and SSA, SI is proposed as an alternative pathway for improving food supply and meeting consumer demands in an environmentally sustainable way. Globally, we should implement SI as a portfolio of investments that, in the aggregate and in the local context, results in more nutritious food and less environmental damage.

SI is necessary but not sufficient for achieving universal food security. The complexity of the food system and the need for complementary and often synergistic investments across multiple sectors present implementation challenges. At the national level, where most policies are designed, and finances are allocated, a whole-of-government, multi-sector approach is needed. Complementing the public sector, businesses bring critical knowledge, skills, and resources to ensure the continued benefits that emerge from innovation and competition. Informed, responsive, and courageous leadership is essential.

Responses