Synergistic effect of AP/KP composite oxidizers prepared by electrostatic spraying and promotion of aluminum combustion performance

Introduction

Oxidizers with high oxygen content, high density, good thermal properties and no generation of solid products can greatly improve the oxygen content of metal fuels and explosives with negative oxygen balance system1,2,3,4,5,6, and promote the energy release of the composite system7,8. Additionally, the interaction between oxidizers, fuels, and explosive compounds can affect both the energy release rate and the efficiency of the system. Compared with potassium perchlorate (KP)9,10,11, lithium perchlorate (LiP), ammonium nitrate (AN)12,13, and ammonium dinitramide (ADN)14,15, ammonium perchlorate (AP) has several advantages, including good thermochemical stability (thermal decomposition temperature of 290 ℃)16,17,18, favorable ignition properties, and condensed combustion products that are entirely gaseous19, making it widely studied in the field of propellants20,21,22,23. However, AP also has some drawbacks24, including an effective oxygen content of only 34.0%25, which may not meet the oxygen demand of certain systems. Its low theoretical density (1.95 g·cm-3), high hygroscopicity (water absorption rate > 2.5 wt% at 80% relative humidity), high mechanical sensitivity, and low enthalpy of formation (-288 kJ·mol-1) restrict its application in propellants26. The low enthalpy of formation of AP significantly impacts propellant performance. This lower value can reduce energy output and specific impulse, potentially limiting the thrust and overall efficiency of the propellant27.

Composite oxidizers, which combine two or more individual oxidizers, seek to harness the advantages of each oxidizer to improve their overall performance28,29,30,31,32,33. Zi et al.34 prepared different proportions of AN and KP mixed crystalline co-precipitates (MCC) via solvent evaporation to replace AP. The results demonstrated that AN/KP composites exhibited mechanical sensitivity (reduced impact sensitivity from 25 to 15%), explosive performance, and specific impulse equivalent to pure AN, while also possessing the high density, effective oxygen content, and thermal stability of KP (decomposition temperature increased from 170 ℃ to 200 ℃). Cheng et al.35 prepared a series of AP co-crystals with 18-crown-6 (18C6), benzo-18-crown-6 (B18C6), and dibenzo-18-crown-6 (DB18C6) using a solvent/anti-solvent method. They significantly reduced the hygroscopicity of AP by leveraging the hydrophobic properties of phenyl groups in crown ethers, achieving approximately a 30% reduction in water absorption. Additionally, they enhanced its thermal decomposition by lowering the activation energy from 117 kJ·mol-1 to 90 kJ·mol-1.Thus, combining different oxidizers is a promising approach to improving the performance of individual oxidizers.

Electrostatic spraying, as a method for material compounding, allows precise control over preparation process parameters, enabling the production of samples with suitable morphology and size. It is widely used in the preparation of composite energetic materials36,37,38,39,40. The principle of electrostatic spraying involves using electrostatic forces to atomize a solution into fine droplets. When the surface charge of the droplets reaches a certain limit, they disintegrate, precipitating the solute and depositing it41,42,43. Qin et al.44 prepared Boron (B)@polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)/AP composite particles using electrostatic spraying, where AP effectively prevented the hygroscopicity and oxidation of B while improving its ignition and combustion performance. The ignition delay time was shortened from 13.5 milliseconds to 8.5 milliseconds, and the combustion efficiency was increased by 15%. Zhang et al.45 leveraged electrostatic spraying to prepare aluminum (Al)@adhesive (Viton A, F2602)/AP particles. The gaseous decomposition products of AP were utilized to accelerate the combustion of Al powder, resulting in a 25% increase in the combustion rate compared to the mechanically mixed sample. Therefore, electrostatic spraying is an effective technique for optimizing the performance of composite materials.

Compared to other common oxidants, KP boasts a high oxygen content (46.2%), a high density (2.52 g·cm-3), and a large negative enthalpy of formation (-433.1 kJ·mol-1)46,47,48. Introducing KP into AP offers a new strategy for obtaining composite oxidizers with high energy, low mechanical sensitivity, and excellent combustion performance. Additionally, the precise control of the preparation process via electrostatic spraying enables the production of AP/KP composite oxidizers featuring uniform composition, adjustable structures, and high energy density. Through SEM, EDS, XRD, XPS, TG-DSC-FTIR-MS, and sensitivity testing, the morphology, composition, thermal properties, and safety of the AP/KP composite oxidizers were analyzed to evaluate the impact of different preparation methods on oxidizer performance. The samples were incorporated into typical metallic Al powder fuel, and their combustion heat, pressure-time curves, and combustion processes were tested. This study offers both experimental and theoretical insights into improving oxidizer performance using the electrostatic spraying method.

Experimental

Molecular dynamics simulation calculation

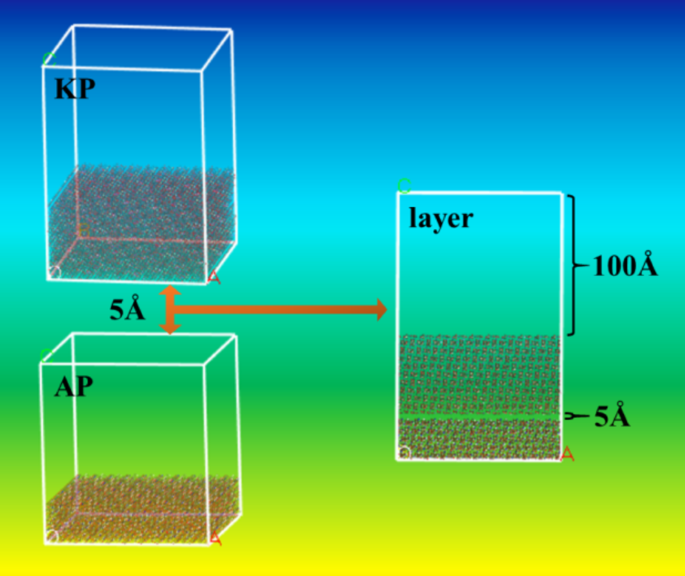

To investigate the feasibility of combining the two oxidants, AP and KP, at the molecular level and to identify their optimal combination ratio, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted to calculate and compare the relevant interfacial parameters. The crystal data of AP and KP were obtained from the Cambridge Structural Database System (CSDS) of the University of Cambridge and subsequently imported into Materials Studio (MS) software. These structures were cleaned, organized, and optimized using the Universal force field with an ultra-fine accuracy setting (5 × 10− 7). The optimized crystal structure is presented in Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of AP and KP. (a) the crystal structure of AP (b) the crystal structure of KP.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted on the optimized AP and KP crystal cells, and their growth morphology was simulated using the Growth Morphology method. The crystal morphology prediction indicated that the (101) crystal planes had the highest proportion in both AP and KP crystal structures, accounting for approximately 50% of the total crystal planes, and exhibited strong interactions with tightly packed molecules. Therefore, the (101) crystal planes were extracted separately from the AP and KP crystal cells. To ensure unit cell size compatibility, 10 × 10 supercells were constructed and placed into a periodic simulation box. The AP thickness was set to five layers, and the KP thickness was determined according to the specified ratio. A 5 Å vacuum layer was introduced between the two systems to mitigate marginal effects on the calculation results. A 100 Å vacuum layer was introduced along the z-direction to accommodate interface systems with varying AP and KP ratios. To ensure statistically reliable simulation results, the number of atoms in all systems ranged from 50,000 to 100,000. The schematic diagram of the AP/KP interface system construction is presented in Fig. 2.

Diagram of AP and KP interface system construction.

The constructed system was first optimized using the Geometry Optimization function in the Forcite module, followed by an Anneal simulation to approximate the structural state of molecules at room temperature. Subsequently, the resulting structure was re-optimized using the Geometry Optimization function. Finally, the Dynamics function was employed to conduct dynamic simulations. A Universal force field was applied throughout these procedures, and an ultra-fine calculation accuracy setting was employed. The energy convergence accuracy was set to 14.184 × 10− 4 kJ·mol− 1, the force convergence accuracy to 0.02092 kJ·mol− 1, and the displacement convergence accuracy to 5 × 10− 5 Å.

In molecular dynamics analyses, intermolecular binding energy represents the amount of work required to overcome intermolecular attraction; hence, it corresponds to the negative value of the interaction energy (i.e., Ebind=-ΔE). A larger binding energy value indicates a more stable AP/KP composite system and a stronger intermolecular interaction between AP and KP. The interaction energy (ΔE) is given by:

In the formula, Etotal is the total energy, kJ·kg− 1; EAP is the partial energy of AP, kJ·kg− 1; EKP is the energy of the KP portion, kJ·kg− 1.

Cohesive energy density (CED) represents the energy required per unit volume to vaporize one mole of a condensed material by overcoming intermolecular forces. It primarily reflects the interactions between functional groups. In general, molecules with more polar functional groups exhibit stronger intermolecular forces and therefore higher cohesive energy densities. The cohesive energy density (CED) is expressed as:

In the formula, CEDtotal is the total cohesive energy density between AP and KP, kJ·cm− 3 Vtotal is the total volume of AP and KP, cm− 3; VAP and VKP represent the volumes of AP and KP, respectively, in cm− 3.

Materials

The raw ammonium perchlorate (AP) was industrial-grade B-type III, supplied by the Liming Chemical Research and Design Institute Co., Ltd. The raw potassium perchlorate (KP) was supplied by Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Fine spherical Al powder (FLQT4), with a particle size of (6 ± 1.5) µm, was provided by Angang Industrial Fine Al Powder Co., Ltd. Acetone and anhydrous ether were purchased from Beijing Tongguang Fine Chemicals Company, and deionized water was prepared in the laboratory. All reagents were of analytical-grade purity and were used as received.

Sample preparation

At room temperature, an anhydrous ether solution was used as a non-solvent. First, 0.4 g of AP and 0.6 g of KP were added to 30 mL of anhydrous ether solution to prepare a suspension, which was ultrasonically dispersed for 20 min. The suspension was then filtered using filter paper and was washed 2–3 times with anhydrous ether solution. Finally, the filtered sample was dried in a 60 °C oven with air circulation for 2 h, resulting in the physically mixed sample labeled AP/KP-1#.

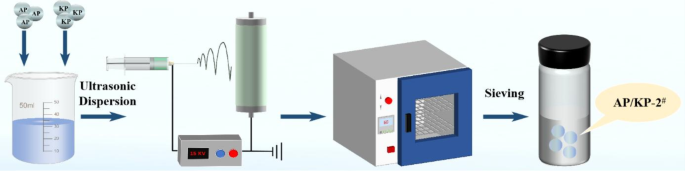

The preparation process of electrostatic spray sample AP/KP is shown in Fig. 3. At 40 °C, an acetone-water solution (acetone: water = 4 mL: 1 mL) was used as the solvent. First, 0.4 g of AP and 0.6 g of KP were added to 30 mL of the acetone-water solution to form a mixed solution, which was ultrasonically dispersed for 20 min to ensure uniform dissolution and even dispersion of the solutes. The prepared solution was then drawn into a 5 mL syringe, with a metal nozzle attached to the syringe tip, and the syringe was pressed to expel air from both the chamber and the nozzle. The syringe was then mounted horizontally on a peristaltic pump, with a layer of Al foil placed on the surface of a metal collector plate for sample collection. The positive voltage was set to 15 kV, the negative voltage to 0 kV, the distance from the nozzle to the collector plate to 15 cm, and the feed rate of the peristaltic pump to 0.3 mm·min− 1. The protective glass was then closed, and the power supply was turned on. Upon completion, the peristaltic pump and power supply were turned off, the Al foil containing the collected sample was removed, and the sample was dried in a 60 °C air-circulating oven for 2 h. Finally, the sample was sieved, yielding the electrostatic spray sample labeled AP/KP-2#.

Schematic illustration of the preparation process of AP/KP-2#.

At room temperature, 0.8 g of oxidant and 0.4 g of Al powder were added to 30 mL of anhydrous ether to prepare a suspension, which was sonicated for 20 min. The suspension was then filtered using filter paper and washed 2–3 times with anhydrous ether. Finally, the sample was dried in a blast drying oven at 60 °C for 2 h, resulting in a mixed sample of oxidant and Al powder, including AP/Al, KP/Al, AP/KP-1#/Al, and AP/KP-2#/Al.

Characterization

The microstructure and elemental composition of AP, KP, AP/KP-1#, and AP/KP-2# were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, SU8020, Japan) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, HORIBA EMAX mics2, Japan). The components of the four samples and their condensed combustion products were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, D8 ADVANCE, Germany) with a scanning range of 5° to 90° and a scanning rate of 6°·min− 1. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet IS10, USA) was used to characterize the composition of the four samples, with a spectral range of 400–4000 cm− 1. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo escalab 250XI, USA) was employed to investigate the elemental energy spectra of the four samples. The thermal decomposition properties of the AP/KP composite oxidizer were tested using a thermal analyzer (TG-DSC-MS-FTIR), with a sample mass of 3 mg, heating rates of 5, 10, and 20 K·min− 1, an argon atmosphere, and a flow rate of 50 mL·min− 1.

The combustion heat of AP, KP, AP/KP-1#, and AP/KP-2# was tested using an oxygen bomb calorimeter (PARR 6200, Parr Instrument Company, Illinois, USA). The sample mass was 200 mg, the atmosphere was oxygen, and the pressure was 3 MPa. Each sample was tested three times under the same conditions, and the average combustion heat was calculated. The pressure-time curves of the four samples were measured using a custom-made closed-bomb apparatus. The sample mass was 50 mg, the atmosphere was oxygen, and the pressure was 2 MPa. The power supply voltage was 24 V, and data were collected at intervals of 0.001 s. The ignition and combustion processes of the four samples were tested in an open environment using a laser ignition testing apparatus, with high-speed camera (i-SPEED 726, iX Cameras, UK) footage captured at 10,000 fps and an exposure time of 50 µs. The oxidizer and Al powder were mixed at a 2:1 mass ratio to ensure complete combustion, with a sample mass of 30 mg. The laser power supply was set to 20 W, and the combustion time was 500 ms.

The mechanical sensitivity of the four oxidizers was tested according to the GJB-772 A-1997 standard using a WL-1 type impact sensitivity apparatus and a WM-1 friction sensitivity tester. For the impact sensitivity test, the drop hammer weight was 10 kg, the sample mass was 50 mg, and sensitivity was determined after 50 trials and expressed as the probability of explosion (%). For the friction sensitivity test, the pendulum weight was 1.5 kg, the swing angle was 90°, the sample mass was 20 mg, and the pressure was 3.92 MPa. The sensitivity was also determined after 50 trials and expressed as the percentage of explosions.

Results and discussion

Analysis of calculation results

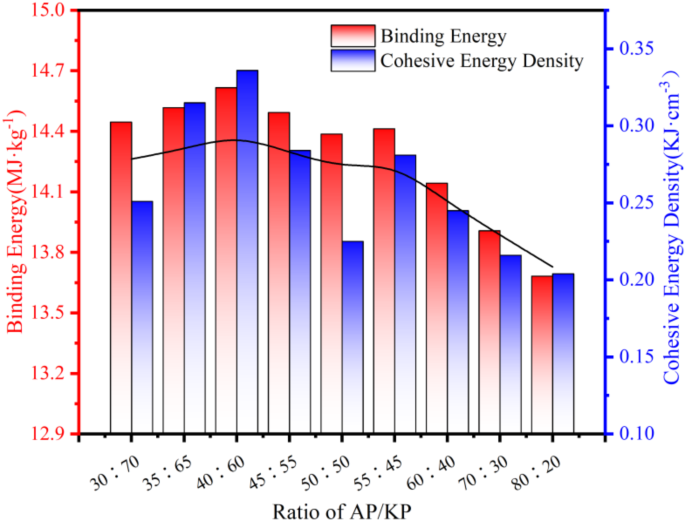

After the AP/KP composite structure achieved equilibrium via the Dynamics module simulation, the Energy and Cohesive Energy Density functions in MS software were employed to calculate the system energy and cohesive energy density based on the final five frames of the trajectory, and the mean values were recorded. The results are presented in Table 1; Fig. 4.

Simulation results of AP/KP composite system.

Generally, higher intermolecular binding energy and cohesive energy densities correspond to greater work required to overcome intermolecular attractions, resulting in more stable intermolecular binding. According to the simulation results in Fig. 4, the binding ability between AP and KP initially increases, then decreases, and subsequently increases again as the AP content rises, exhibiting two peaks at the 40:60 and 55:45 ratios. It is speculated that this trend arises from changes in molecular composition. When KP content is high, the larger relative molecular weight of KP leads to stronger van der Waals forces with AP, increasing the system’s binding energy. Conversely, when the AP content is high, the increased concentration of NH4+ groups in AP provides more H atoms to form hydrogen bonds with O atoms in KP. Therefore, the binding ability between AP and KP follows an increase–decrease–increase pattern as the AP content rises. At an AP/KP ratio of 40:60, both the binding energy and cohesive energy density attain their maximum values. Under these conditions, the intermolecular binding energy is 14.616 MJ·kg− 1 and the cohesive energy density is 0.336 kJ·cm− 3. Hence, based on molecular dynamics parameter comparisons, the optimal AP/KP composite oxidant ratio is 40:60.

Composition and structure analysis

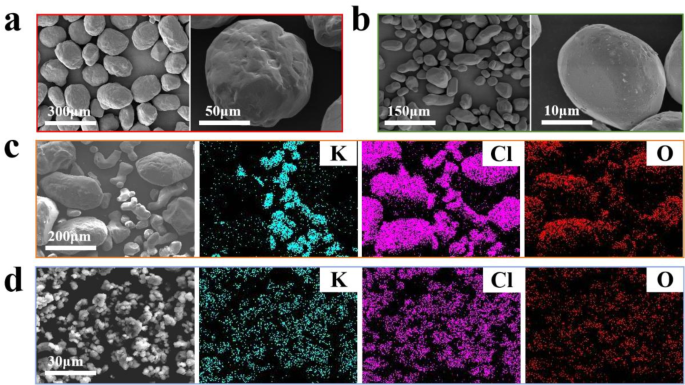

(a) SEM image of AP, (b) KP, (c) AP/KP-1# along with its elemental distribution, and (d) AP/KP-2#.

The SEM images of AP, KP, and the two composite oxides are shown in Fig. 5. The AP particles (Fig. 5a) are spherical or nearly spherical, with rough surfaces, uniform in size and distribution, and exhibit good dispersion. The KP particles (Fig. 5b) are smaller in size compared to AP and are rod-shaped or spherical with smooth surfaces. From Fig. 5c, it is observed that there is a noticeable size difference between AP and KP particles in AP/KP-1#, with no change in morphology. In Fig. 5d, the morphology of AP/KP-2# is regular, though some agglomeration occurred, and the particle size is smaller compared to AP/KP-1#. This is likely due to the faster solvent evaporation during the electrostatic spraying process, where the droplets evaporated before reaching the collector. Consequently, the shorter nucleation and growth time of crystals hindered the formation of larger particles, leading to agglomerates on the tin foil. The EDS spectra of elemental K in Fig. 5c and d show a uniform distribution of K on the surface of the KP particles. After electrostatic spraying, elemental K is also uniformly distributed on the surface of the AP/KP-2# samples, indicating successful uniform mixing of AP and KP during the electrostatic spraying process.

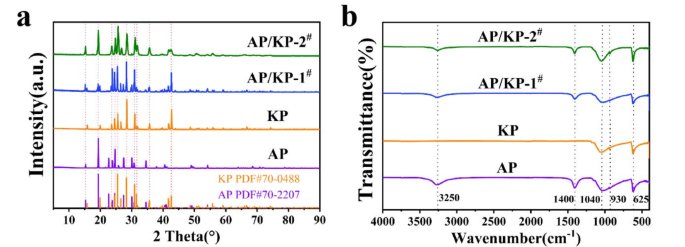

(a) XRD patterns of AP, KP, AP/KP-1# and AP/KP-2# (b) FTIR spectra.

Figure 6a shows the XRD spectra of the four oxidizers. The diffraction peaks of AP/KP-1# and AP/KP-2# at 15.29°, 19.28°, 24.59°, and 30.88° correspond to the characteristic diffraction peaks of AP, while the peaks at 25.55°, 31.56°, 35.56°, and 42.72° match the characteristic diffraction peaks of KP. Additionally, Fig. 6b presents the FTIR spectra of the four oxidizers. The raw AP exhibits absorption peaks at approximately 3250, 1400, 1040, 930, and 625 cm− 1. The peak near 3250 cm− 1 is attributed to the N-H stretching vibration, while the peak around 1400 cm− 1 corresponds to the N-H bending vibration. The absorption peaks at approximately 1040, 930, and 625 cm− 1 are due to the ClO4− stretching vibration. For the raw KP, absorption peaks are observed at 1040, 930, and 625 cm− 1, which are also attributed to the ClO4− stretching vibration. The absorption peaks of the two AP/KP composite oxidizers are essentially a superposition of the peaks of raw AP and KP, with no new absorption peaks observed.

By comparing the XRD and FTIR absorption peaks of AP, KP, and the AP/KP composite oxidizers, it can be concluded that the electrostatic spraying method did not alter the spatial atomic distribution within the crystal structure of the raw materials. The sharp diffraction peaks and high peak intensities indicate that the crystal structure of the electrostatic spray samples remained unchanged, with well-preserved crystallinity.

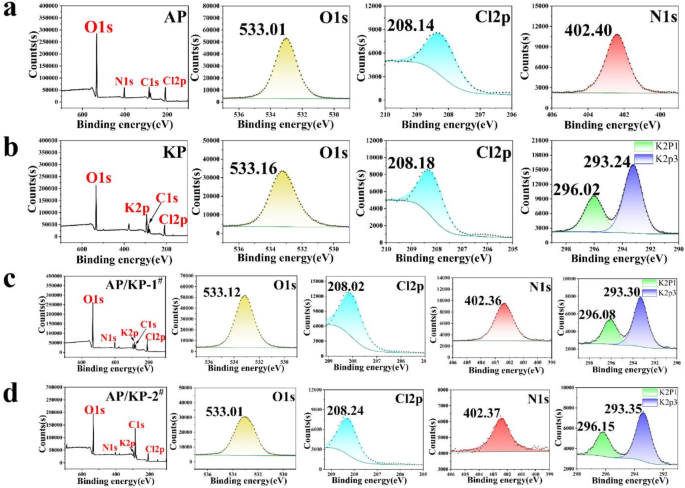

XPS spectra and split-peak fitting spectra of (a) AP, (b) KP, (c) AP/KP-1# and (d) AP/KP-2#.

By comparing the XPS spectra and peak fitting results of raw AP, KP, and the different AP/KP composite oxidizers (Fig. 7a–d), it was found that the main peaks in AP correspond to N1s, Cl2p, and O1s, while the main peaks in KP correspond to K2P, Cl2p, and O1s. The N1s peak near 402.40 eV is attributed to the N in NH₄, the K2P peaks near 292.03 eV and 293.24 eV correspond to K in K-X, the Cl2p peak near 208.14 eV is due to Cl in ClO4− and the O1s peak near 533.01 eV is related to O in Cl-O. After combining AP and KP using the electrostatic spraying method, no significant shifts in the positions of the N1s, K2P, Cl2p, and O1s peaks were observed, indicating that in the AP/KP-2# sample, AP and KP remain physically adsorbed without undergoing chemical reactions to form new substances.

Analysis of safety performance

Mechanical sensitivity test results of AP, KP, AP/KP-1# and AP/KP-2#.

The mechanical sensitivity of raw AP, KP, AP/KP-1#, and AP/KP-2# was tested, and the results are presented in Fig. 8. Compared to raw AP, the impact sensitivity of AP/KP-1# decreased by 24%, and the friction sensitivity decreased by 36%, indicating a reduction in mechanical sensitivity in the mixed system due to the addition of the relatively insensitive KP. Compared to AP/KP-1#, the impact sensitivity of AP/KP-2# decreased by 12%, and the friction sensitivity decreased by 16%. This further reduction in mechanical sensitivity is attributed to the lower sensitivity of KP and the intermolecular interactions between AP and KP formed during the electrostatic spray process.

Thermal performance

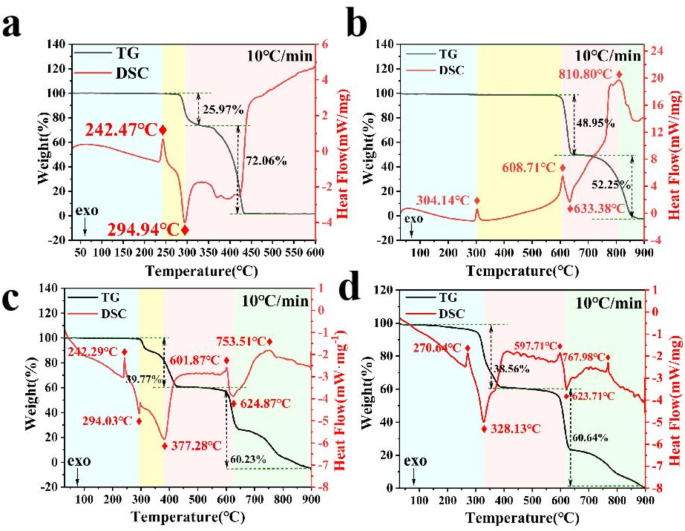

TG-DSC curves of (a) AP, (b) KP, (c) AP/KP-1# and (d) AP/KP-2# at a heating rate of 10 °C-min− 1.

To assess the onset temperature of oxidation and the thermal stability parameters of the samples, TG-DSC curves were measured at a heating rate of 10 °C·min− 1, as shown in Fig. 9a–d. The thermal decomposition curve of AP/KP-1# is essentially a combination of the AP and KP curves, which can be divided into four stages: low-temperature decomposition of AP, high-temperature decomposition of AP, thermal decomposition of KP, and the melting endotherm and evaporation of KCl, a KP decomposition product. In contrast, the thermal decomposition curve of AP/KP-2# only exhibits three decomposition stages: high-temperature decomposition of AP, thermal decomposition of KP, and the melting endotherm and evaporation of KCl.

For AP/KP-1#, the low-temperature decomposition peak of AP shifted from 294.94 °C to 294.03 °C, while the high-temperature decomposition peak of KP shifted from 633.38 °C to 624.87 °C. For AP/KP-2#, the high-temperature decomposition peak of KP shifted from 633.38 °C to 623.71 °C, and the high-temperature decomposition peak of AP was 328.13 °C, which is 49.15 °C lower than that of AP/KP-1#. Compared to AP/KP-1#, the AP/KP-2# composite prepared via the electrostatic spray method achieves molecular-level mixing of AP and KP, producing smaller and more uniform particles. This increases the surface area-to-volume ratio, exposing more decomposition reaction sites and enhancing the interactions between KP and AP, thereby further reducing the energy barrier for KP decomposition. Additionally, the partially agglomerated particles facilitate effective heat and mass transfer between AP and KP during thermal decomposition. The shortened heat transfer distance raises the local temperature of adjacent KP particles during AP decomposition. This preheating effect lowers the energy required to initiate KP decomposition, enabling the heat released by AP to accelerate the KP decomposition process, thereby further reducing the peak temperature of KP’s high-temperature thermal decomposition.

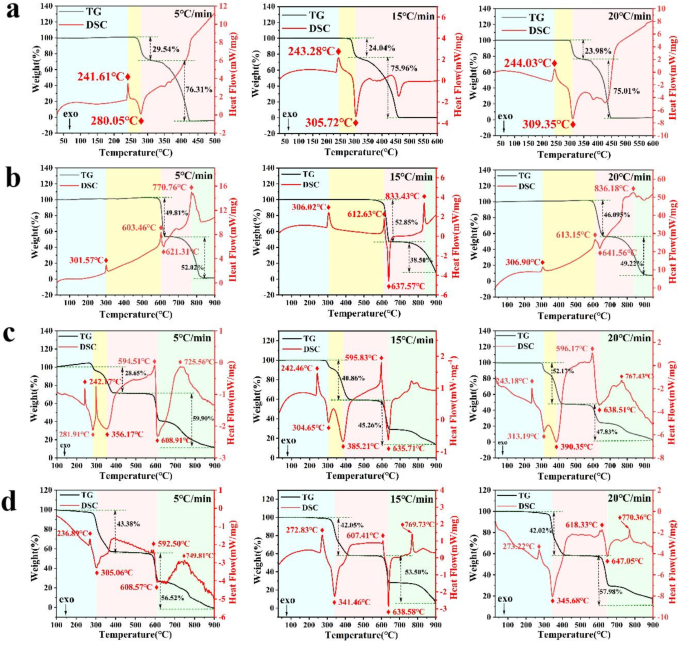

TG-DSC curves of (a) AP, (b) KP, (c) AP/KP-1# and (d) AP/KP-2# at different heating rates.

To obtain the kinetic parameters of the samples under slow heating oxidation, the TG-DSC curves were also measured at heating rates of 5 °C·min− 1, 15 °C·min− 1 and 20 °C·min− 1, as shown in Fig. 10a–d. Using the Kissinger method (Eq. 3) and the Flynn-Wall-Ozawa method (Eq. 4), the linear slopes of ln(β/Tp2) versus 1/Tp and lgβ versus 1/ Tp were calculated by the least squares method. The non-isothermal reaction kinetic parameters of the AP/KP composite oxidizers under slow heating oxidation were then calculated, and the results are shown in Table 2.

In Table 2, Tp1 represents the low-temperature decomposition peak of AP, Tp2 represents the high-temperature decomposition peak of AP, and Tp3 represents the decomposition peak of KP. As shown in Table 2, taking 10 °C·min− 1 as an example, the thermal decomposition activation energy of AP/KP-1# was reduced compared to the raw AP and KP. The low-temperature decomposition activation energy of AP decreased from 112.43 to 115.89 kJ·mol− 1 to 109.97–113.59 kJ·mol− 1, while the activation energy of KP’s decomposition decreased from 448.32 to 440.62 kJ·mol− 1 to 286.34–286.46 kJ·mol− 1, suggesting that physical mixing can lower the energy barrier for thermal decomposition to some extent. In AP/KP-2#, the activation energy for the thermal decomposition of KP decreased from 448.32 to 440.62 kJ/mol− 1 to 222.80–226.11 kJ·mol− 1, showing that the energy required for KP’s thermal decomposition in AP/KP-2# was significantly reduced. Additionally, the calculated results using both the Kissinger and Ozawa methods showed good correlation (greater than 0.99). These high correlation coefficients indicate that the data are highly consistent with the models and that the models fit well, confirming the stability and reliability of the derived kinetic parameters. Moreover, the agreement among dynamic analysis, experimental results, and MD simulation findings further validates the reliability of the current study. For instance, the decrease in KP activation energy (from 448.32 kJ·mol− 1 to 222.80 kJ·mol− 1) and premature thermal decomposition observed in TG-DSC results align with MD simulations, which indicate high binding energy and cohesive energy density.

The reduction in the activation energy of the composite oxidizers’ thermal decomposition suggests that the combustion reaction with the Al powder in an oxygen-free environment is more readily activated, resulting in faster and more complete energy release within the explosive system, thereby increasing the energy utilization efficiency. Therefore, we explored the energy release rate and efficiency of the system by adding Al powder to different oxidizer samples.

Combustion performance

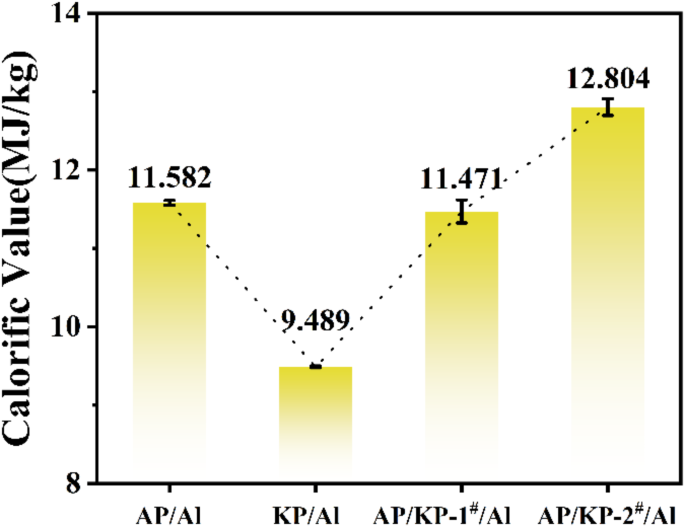

Calorific value of combustion of AP, KP, AP/KP-1# and AP/KP-2# and Al powder.

Figure 11 shows the combustion heat values of different oxidizer samples with Al powder. As illustrated in Fig. 11, AP/KP-2#/Al has the highest combustion heat value, reaching 12.804 MJ·kg− 1, which is an increase of 0.613 MJ·kg− 1 compared to AP/KP-1#/Al. This improvement is attributed to the uniform combination of AP and KP through electrostatic spraying, which shortens the mass transfer distance between the oxidizer and fuel. Moreover, the uniform combination of KP and AP increases the specific surface area, and the high effective oxygen content of KP provides more oxygen during the combustion process. This promotes complete combustion in the constant volume combustion chamber, enhancing the combustion efficiency of Al powder.

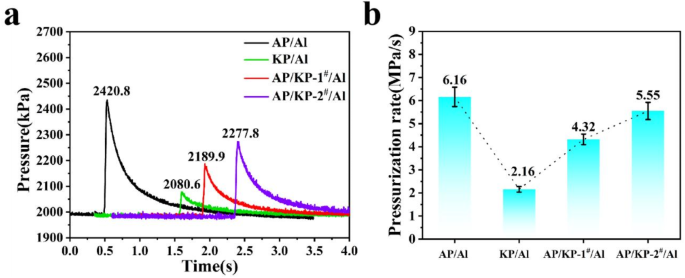

(a) P-t curves of AP, KP, AP/KP-1# and AP/KP-2# and Al powder samples and (b) pressurization rate.

The AP/Al sample exhibits the highest average peak pressure and pressurization rate in a closed environment, followed by AP/KP-1#/Al and AP/KP-2#/Al, with average peak pressures of 2189.9 kPa and 2277.8 kPa, respectively, which exceed that of KP/Al by 109.3 kPa and 197.2 kPa, respectively. According to the ideal gas law, when the volume is constant (as the combustion chamber volume is fixed), the pressure inside the chamber is related to the amount of gas produced and the combustion temperature. As shown in Fig. 12, the combustion heat value of AP/KP-2#/Al is higher than that of AP/Al, but AP/Al generates more gas, which dominates the peak pressure and results in a higher peak pressure.

Furthermore, due to the lower thermal decomposition temperature of AP, the AP in AP/KP-2# reacts first when ignited with Al, releasing a large amount of heat. This heats the surrounding oxidizer and fuel, inducing the combustion of KP, which has a higher effective oxygen content, along with Al, releasing more heat. This accelerates the combustion reaction rate and increases the pressurization rate of the system.

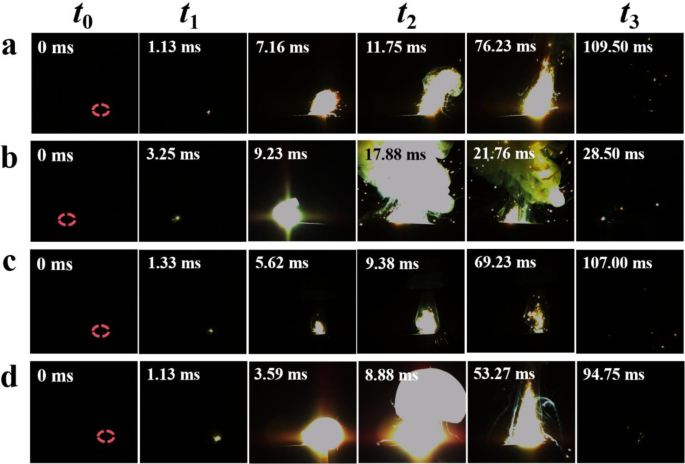

Laser ignition combustion process of (a) AP/Al, (b) KP/Al, (c) AP/KP-1#/Al and (d) AP/KP-2#/Al.

The ignition and combustion photographs of AP, KP, and the different oxidizer samples are displayed in Fig. 13. The ignition delay time, t₁, is defined as the time from when the laser is irradiated on the sample surface at t₀ until the sample absorbs photon energy, accumulates heat, and ignites. The ignition growth time, t₂, is defined as the time from ignition until the flame grows to its maximum size. The combustion time, t₃, is defined as the time from the maximum flame size until the sample continues to burn and almost extinguishes.

The results show that AP/Al has the shortest ignition delay time and a fast ignition growth rate. In visual terms, KP/Al exhibits the most intense combustion, but the flame duration is the shortest, and it takes the longest time to reach the maximum flame height. This is because KP has a high thermal decomposition temperature and requires more energy to ignite, making ignition more difficult.

Additionally, after combustion, a small amount of unreacted solid residue remained visible in the ignition tray of the AP/Al and AP/KP-1#/Al samples. When the laser ignition device was restarted, combustion could still occur, indicating that the combustion reaction between AP and Al in an atmospheric environment was incomplete, and energy release was insufficient.

The combustion start time for AP/KP-2#/Al is the same as for AP/Al, earlier than for KP/Al and AP/KP-1#/Al. Compared to KP/Al, the combustion start time of AP/KP-2#/Al is reduced from 3.25 ms to 1.13 ms, and the flame intensity is second only to KP/Al. The ignition growth time is significantly shortened to 8.88 ms. AP/KP-2#/Al not only maintains a high energy release capability but also significantly reduces the ignition difficulty of KP. This demonstrates that the AP/KP composite oxidizer prepared by electrostatic spraying, when combined with Al powder, exhibits superior combustion and energy release performance compared to mechanically mixed samples.

XRD analysis of condensed combustion products

XRD spectra of laser ignition condensed combustion products of AP/KP composite oxidizer and Al powder.

To further investigate the energy release of the electrostatic spray samples, the condensed combustion products of the composite oxidizer were collected and evaluated using XRD analysis (Fig. 14). The results show that the primary condensed combustion products of the AP/KP composite oxidizer and Al powder is Al2O3. Additionally, trace amounts of AlN were detected, but their peak intensities were too low to be labeled in the figure.

Notably, after combustion, small amounts of unreacted AP, KP, and Al were also present. This may be due to the sample being in powder form, leading to incomplete combustion. From the intensity of the XRD diffraction peaks, it can be inferred that the residual AP and KP content after the combustion of AP/KP-1#/Al exceeds that in AP/KP-2#/Al. This observation aligns with the earlier finding that a small amount of unreacted solid residue was still visible in the ignition tray after the combustion of the AP/KP-1#/Al sample. This confirms that the combustion performance of the electrostatic spray samples combined with Al powder is superior to that of the physically mixed samples.

Reaction mechanism

Slow oxidation reaction mechanism

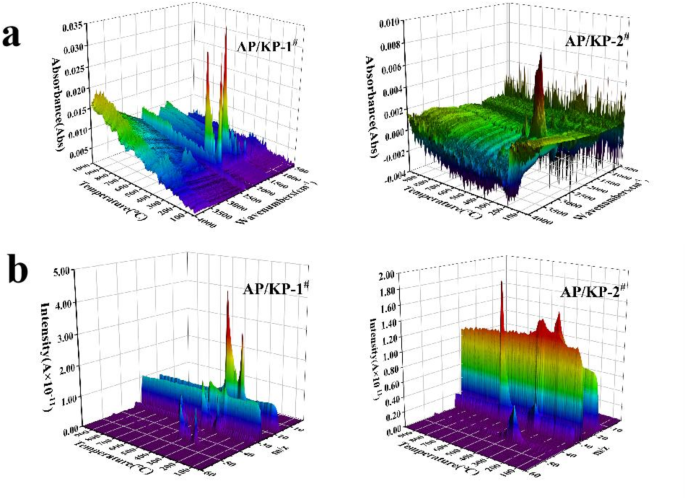

FTIR and MS curves of the thermal decomposition products of (a) AP/KP-1# (b) AP/KP-2#.

The FTIR curves of the decomposition gas products (Fig. 15a) and the MS curves (Fig. 15b) show that the infrared absorption peaks of the decomposition gas products from the AP/KP composite oxidizers predominantly occur within the temperature range of 250–350 °C. This correlates with the weight loss region in the TG curves and the characteristic peak temperatures in the DSC curves. At this point, a large amount of gas is generated as AP undergoes decomposition. As the temperature increases, the decomposition process accelerates, with both the types and quantities of decomposition products increasing and peaking at approximately 350 °C, corresponding to the high-temperature decomposition stage of AP. The possible gas products from AP decomposition include NH3 (1640 and 1600 cm− 1), N2O (2240 and 2200 cm− 1), NO (1900 cm− 1), and HCl (3000 cm− 1), with N2O (2240 and 2200 cm− 1) showing the strongest intensity. Notably, the infrared characteristic peaks of N2O are observed during both the low- and high-temperature decomposition stages of AP.

From the MS curves of the decomposition gas products (Fig. 15b), m/z = 18 and m/z = 32 exhibit intensity at the beginning of the reaction, possibly due to H2O and O2 in the test environment affecting the results. Two peaks of ion fragments appear around 300 °C and 600 °C, which is consistent with the FTIR results and corresponds to the decomposition peak temperatures of AP and KP. The ion fragments around 300 °C include NH3 (m/z = 17), H2O (m/z = 18), NO (m/z = 28), O2 (m/z = 32), and N2O (m/z = 44), which are potential decomposition products of AP. At around 600 °C, only O2 (m/z = 32) is present, with the O2 peak reaching its maximum intensity at this point.

A comparison of the thermal decomposition curves of AP/KP-1# and AP/KP-2# at different heating rates, as presented in Figs. 9 and 10, revealed that, in contrast to AP/KP-1#, only the high-temperature decomposition peak of AP remains in the thermal decomposition curve of AP/KP-2#. In the context of the slow thermal decomposition process of AP at normal pressure, it is generally accepted that the initial decomposition of AP involves the dissociation of protons transferring from NH4+ to ClO4− to generate NH3 and HClO4, with two competing processes of sublimation and decomposition49,50.

Subsequently, a series of complex degradation processes of HClO4 occur in the gas phase, with its products undergoing oxidation reactions with NH3. The potential decomposition steps are as follows51:

Consequently, the primary gas-phase product detected by FTIR in the initial stage of AP decomposition is N2O, along with a small amount of NO. During the high-temperature decomposition stage of AP, the desorption of NH3 intensifies its oxidation by HClO4 degradation products, with exothermic decomposition becoming more dominant. As a result, the increase in HNO (Eq. 10) produced by NH₃ oxidation accelerates Reaction 12, leading to the accumulation of NO, which can be detected by FTIR. Simultaneously, HCl was detected, with its concentration increasing as the temperature rises52. Thus, additional decomposition steps may occur during the high-temperature decomposition stage of AP50,51:

Therefore, it can be inferred that during the decomposition of AP/KP-1#, AP first desorbs NH3 and HClO4. The larger particle size of AP gives it a more regular crystal shape, with only a few small crystal defects on its surface, which weakly adsorb NH3 and HClO4 gases. Desorption and redox reactions occur at relatively low temperatures, resulting in the formation of gas products such as NO2, NO, N2O, O2, and H2O during the low-temperature decomposition stage. HCl produced by the reaction combines with NH₃ to form NH4Cl, which is adsorbed on the surface of AP, marking the end of the low-temperature decomposition stage. However, in AP/KP-2#, the smaller particle size causes natural agglomeration into a fluffy structure with a large specific surface area, allowing it to adsorb higher quantities of NH₃ and HClO4 gases with stronger adsorption forces. Consequently, desorption of NH3 and HClO4 gases and subsequent rapid gas-phase redox reactions only occur at higher temperatures, which explains why only the high-temperature decomposition peak of AP remains in the thermal decomposition curve of AP/KP-2#.

Combustion reaction mechanism

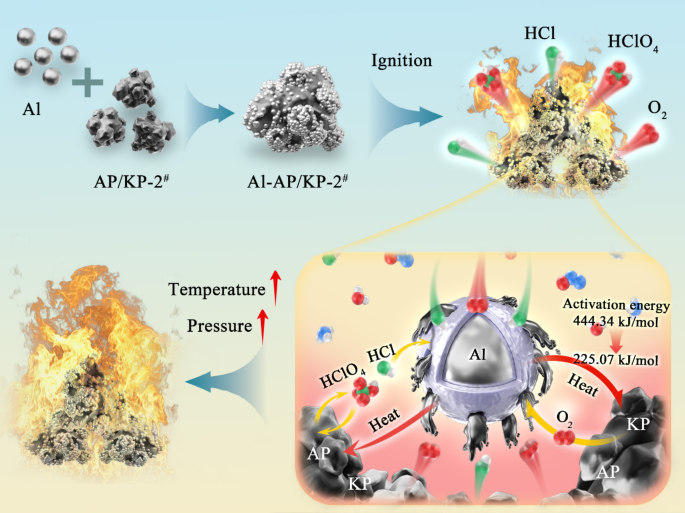

According to the slow oxidation mechanism, at the early stage of ignition, AP in AP/KP-1#/Al and AP/KP-2#/Al ignites first, initiating the reaction. The corrosive gases (HClO4, HCl, etc.) generated during decomposition react with the oxide shell on the aluminum powder surface to form AlCl3, consistent with the phenomenon observed in Fig. 14. AP/KP-2#/Al exhibits a loose and porous structure, with aluminum powder fully mixed and filling the voids, further reducing the mass and heat transfer distance. The gases released during the decomposition of the composite oxidant interact directly with Al particles, facilitating heat release. The decomposition of AP produces significant heat, elevating the local temperature around the Al particles. The corrosive gases etch the inert oxide shell, activating surface reactions and breaking the shell to create more pores. These pores allow external oxygen to enter and form diffusion paths for internal active aluminum. The molten active aluminum reacts with oxygen, releasing significant heat, which increases the system’s temperature and pressure, prompting the release of more gaseous HCl. However, the loose porous structure confines HCl within the system, allowing it to participate in the aluminum powder oxidation reaction rather than escaping, which ultimately accelerates the combustion rate (as shown in Fig. 16). The elevated temperature facilitates the melting of Al, accelerates its reaction with oxygen, and enhances its performance as a high-energy fuel. As shown in Table 1, compared to AP/KP-1#, the activation energy for KP decomposition in AP/KP-2# is significantly reduced from 444.34 to 436.84 kJ/mol− 1 to 225.07–228.28 kJ/mol− 1. This indicates that the energy required for KP decomposition (the reaction threshold) is greatly reduced. The heat released by AP decomposition ignites KP and Al combustion, further enhancing the release of HCl. This heat release results in more complete combustion of the system, giving AP/KP-2#/Al the advantages of shorter ignition time and faster combustion rate.

Reaction mechanism diagram of AP and KP synergistically increasing the combustion efficiency of aluminum powder.

Conclusions

In this study, an AP/KP composite oxidizer was prepared using the electrostatic spraying method to enhance the oxygen content and density of AP while maintaining its energy output. The MD simulation results indicate that the optimal AP to KP ratio is 40:60, where the binding energy and cohesive energy density are the highest. At this ratio, the intermolecular binding energy is 14.616 MJ·kg− 1, and the cohesive energy density is 0.336 kJ·cm− 3. Strong intermolecular interactions enhance the uniformity of AP/KP mixtures, increase the surface area-to-volume ratio, and improve interactions between KP and AP, further lowering the energy barrier for KP decomposition and reducing its activation energy. Furthermore, uniform mixing improves heat and mass transfer between the oxidants (AP/KP) and the fuel (Al), thereby accelerating the combustion reaction rate. These simulation results align closely with the experimental findings. The AP/KP composite oxidizer exhibited a relatively uniform morphology, though some agglomeration occurred, and the K element was uniformly distributed on the particle surfaces. The mechanical sensitivity results showed that the prepared AP/KP composite oxidizer had extremely low mechanical sensitivity, indicating high safety performance. Thermal analysis demonstrated that the homogenous integration of AP and KP in the composite oxidizer shortened the heat transfer distance and significantly promoted the high-temperature decomposition of both AP and KP. During the combustion process with Al powder, the AP/KP composite oxidizer accelerated the combustion reaction rate of the Al powder, resulting in the highest combustion heat value. Laser ignition tests revealed that, compared to AP, KP, and mechanically mixed samples, the AP/KP composite oxidizer exhibited superior combustion and energy release performance. The AP/KP oxidizer prepared by electrostatic spraying addresses the issues of low density, low effective oxygen content, and poor safety in AP, while also enhancing the combustion rate of Al. This study provides both experimental and theoretical references for improving oxidizer performance.

Responses