Systematic bone tool production at 1.5 million years ago

Main

The incorporation of animal resources into the diet of hominins was a milestone in the evolution of our species7, with recent evidence confirming that, by 2.6 Ma, hominins modified mammal carcases with stone tools to access meat8. As a consequence of the encroachment of technology-driven hominins in the carnivore guild, one of the questions that follow is when the utility of animal skeletal elements expanded to include artefact manufacture in addition to their primary role for consumption4,9. This innovation entailed specific knowledge—technological and also anatomical—to be transmitted through social learning in parallel with lithic technology, opening opportunities for new flexible adaptations that contributed to shaping the evolution of Pleistocene hominin cultures.

The Lower Pleistocene bone tool evidence is sparse; limb shaft fragments and horn cores were used—but not intentionally shaped by knapping—in digging and termite foraging activities at several southern African sites dated between 2.4 and 0.8 Ma3,10,11,12,13. At Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, only a few fossils previously purported as bone tools14 have stood scrutiny4,15,16 and include surface finds (that is, out of their original sedimentary context) and isolated specimens dispersed across a stratigraphic interval spanning over 1 million years14. Konso in Ethiopia has also yielded some scattered knapped bone artefacts, including the discovery of a bone handaxe found on the surface but attributed to 1.4 Ma deposits17.

Bone tools shaped by knapping become more frequent in the Eurasian Middle Pleistocene after 500 thousand years ago (ka)5. Bone bifaces are found at several sites from the Levant at Revadim Quarry18, Central Europe at Vértesszőlős19 and Bilzingsleben20, and southern Europe at Fontana Ranuccio and Castel di Guido5, as well as at the Bashiyi Quarry, Chongqing, China21. Possible expedient bone shaft fragments bearing one or more edges with flake removal scars on the cortical or the medullar surface, some of which have been interpreted as wedges or intermediate tools, are present in Europe as early as marine isotope stage 9 at Gran Dolina, Spain22, Schöningen, Germany23,24, and in Italy5 at Castel di Guido, Bucobello, La Polledrara di Cecanibbio and Rebibbia-Casal de’ Pazzi. In East Asia, similar tools are reported throughout the Pleistocene25. Bone tools shaped with techniques such as scraping, grinding and gouging, which allowed the production of diversified and specialized tool types such as spear and arrow points, barbed points, awls and needles, only appear during the Upper Pleistocene in the African Middle Stone Age after 90 ka26,27,28,29 and in Eurasia after 45 ka30,31,32,33,34.

The sparse nature of the early knapped bone tool record has prevented researchers from identifying behavioural consistencies in their production and use, and establish the role they had in early hominin subsistence and cognition. Here we describe a bone tool assemblage from a single horizon securely dated to 1.5 Ma at Olduvai Gorge Bed II, Tanzania, which precedes other evidence of systematic bone tool production by more than 1 million years and sheds new light on the almost unknown world of early hominin bone technology.

The T69 Complex archaeological site

The T69 Complex is located in the Frida Leakey Korongo (FLK) West Gully at Olduvai Gorge, in northern Tanzania (Extended Data Fig. 1). This site is positioned in the stratigraphic interval between Middle and Upper Bed II, in which early Acheulean assemblages are reported. Radiometric and chronostratigraphic data firmly position the T69 Complex site at 1.5 Ma (Methods).

The T69 Complex includes seven trenches excavated between 2015 and 2022 (Methods; Supplementary Information Videos 1 and 2). The archaeological assemblage that yielded the bone tools was deposited within interlayering silts and sands indicative of an alluvial plain environment with alternating decantation and water flow facies. It contains over 10,900 stone tools that are 2 cm or longer, mostly made on locally available quartzite, and numerous smaller lithic artefacts (more than 41,000). The lithic assemblage includes cores (n = 747) and split cobbles (n = 50), pounded (n = 273) and retouched (n = 230) tools, flakes (n = 2,804) and flake fragments (n = 8,358), and is attributed to the Acheulean35 owing to the presence of large cutting stone tools (LCT; n = 37). The assemblage also contains over 9,419 identifiable vertebrate fossils and 13,413 unidentified bone fragments. Abundant fish, crocodile and hippopotamus remains are consistent with lithological data indicating the proximity of water sources. The large mammal assemblage is dominated by bovids and hippopotamus, the latter represented by relatively complete carcasses. Equids, suidae, elephants, rhinoceros and other taxa are also present. Hippopotamus is the most abundant genus, and bones frequently exhibit evidence of anthropogenic manipulation, suggesting that hominins were attracted to the T69 Complex area by the availability of hippopotamus carcasses (Methods; Supplementary Data 1).

The bone tool assemblage

The T69 Complex faunal assemblage, including the bone tools, presents an excellent state of preservation that allows documentation of natural and anthropogenic modifications in detail. Taphonomic and morphometric analyses rule out natural processes to account for the modifications recorded on the 27 specimens identified as bone tools (Methods). Several factors are known to cause flake removals on bone that mimic intentional flaking4, including carnivores gnawing, crocodiles biting, trampling and fracturing to access marrow. Several reasons rule out these factors: carnivore remains amount to less than 1% of the identified specimens. With the exception of two possible tooth marks (Supplementary Data 2), no modifications produced by carnivores are recorded on the T69 Complex bone tools, whereas they are abundant in bone assemblages modified by these agents and yielding fragments bearing flake removals36,37. The fresh appearance of the edges of the tools and the rarity of striations attributable to trampling indicate that this process had minimal effect on the state of preservation of the bone artefacts and cannot be the cause for the numerous invasive flake removals present on them. Experimental breakage of large mammal limb bones for marrow extraction, including elephant bones, has demonstrated that flake removal scars resulting from this activity rarely amount to more than four (Extended Data Fig. 4f–h), they are mostly isolated or, when contiguous, rarely exceed three, and they preferentially occur on the ends rather than the lateral sides of the splinters4,9. T69 Complex faunal fragments display an average of 2.1 flake scars that occur as isolated removals in 84.3% of the specimens (Extended Data Fig. 4b–d), conforming with a pattern typical of limb bone breaking to access marrow. By contrast, the T69 Complex bone tools exhibit an average of 12.9 flake scars per specimen (Extended Data Fig. 4i–k) and are always arranged contiguously and preferentially—but not exclusively—on their lateral edges.

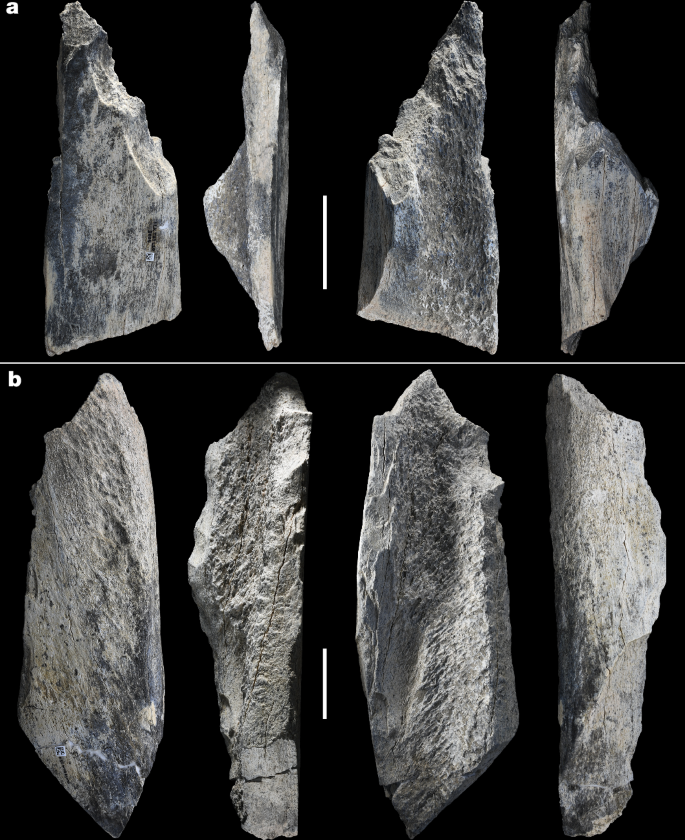

All 27 bone tools were found in situ during excavation (Supplementary Video 3). Eighteen (66.7%) come from bones attributed to mammals heavier than two tonnes (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 2). Among the 16 taxonomically identifiable specimens, eight are from elephant, six are from hippopotamus and two from bovids (Supplementary Data 2). Thus, although the mammal assemblage is dominated by bovids (41.1%), a minimum of 50% of bone tools are made from elephant, which only makes 1.1% of the T69 Complex taxa composition. With the exception of a single proximal portion of a large bovid radius that preserves part of its epiphysis, all tools are exclusively made on limb bone shaft fragments, particularly femora, tibiae and humeri.

a, Indeterminable taxon larger than two tonnes (accession number T69L20-3009). b, Elephant (accession number T79L10-2511). Scale bars, 5 cm. See also Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Videos 4 and 5.

The bone tools display morphological, technological and dimensional characters identifying behavioural patterns previously undocumented at early hominin sites. The surface of flake removals is fresh, which is indicative of the short period of subaerial exposure elapsed between bone tool production and burial. All tools made of hippopotamus limb fragments come from bones broken while they were in a nutritive state. For those made of elephant, both fresh and partially weathered bones were used (Supplementary Data 2), which suggests that hominins accessed fresh carcasses but also defleshed bones. The tools are considerably longer than most of the faunal assemblage and fall within the size range of experimentally broken elephant long bones4 (Extended Data Fig. 4a,e,i). Bone tools made from elephant bones are the largest, ranging between approximately 22 and 38 cm in length, and approximately 8 and 15 cm in width. Tools made from hippo bones are slightly smaller with ranges between approximately 18 and 30 cm in length and approximately 6 and 8 cm in width (Extended Data Fig. 5).

Elephant bone tools bear on average more flake removal scars (µ = 17.3) than those made on hippopotamus bone (µ = 13.3). Among the taxonomically unidentifiable specimens, seven bone tools show sizes and number of flake removal scars that are compatible with those made on elephant or hippopotamus bones. Eight tools are smaller in size and bear on average six flake removal scars. When shaping bone tools, the T69 Complex knappers invested substantial effort in first producing invasive flake removals to shape the tool and, subsequently, regularizing the resulting edges via trimming. These two steps are documented by comparing the breadth of the flake removal scars with the cortical thickness and the shaft fragment size index (Fig. 2a–d). The most invasive flake removal scars on the bone tools are significantly longer (F = 21.17, d.f. = 2 and 461, P < 0.0001) than those on fragments of limb bones fractured experimentally for marrow extraction (Fig. 2a,b). The trimming phase, by contrast, produced numerous small contiguous flake removal scars comparable in size—but not in their arrangement—with those on bone fractured experimentally for marrow extraction, which are generally isolated (Fig. 2c,d). Production of blanks for the largest artefacts required striking heavy and sizeable stone percussors against stationary bones4, whereas morphology of flake removals in all bone tools is compatible with the use of handheld hammerstones during the shaping stage.

a–d, Scatterplot of the breadth for the most invasive (a,b) and all (c,d) removal scars present on the FLK T69 Complex bone tools and on bone fragments produced during experimental (Exp) bone fracturing to expose the marrow of horse9 and elephant4 limb bones compared with the cortical thickness (a,c) and the shaft fragment size index (b,d). The maximum breadth of the largest flake removal scars on the bone tools and on fragments of limb bones fractured for marrow extraction demonstrates that the former are considerably larger irrespective of the cortical thickness or the shaft fragment size index. The difference in trend observed when considering all flake removal scars is probably due to the production of numerous small contiguous retouch flakes to shape the bone tool edges. e,f, Length and width (e) and length and weight (f) comparisons between the T69 Complex bone tools and the lithic assemblage found in the same horizon are shown. Bone tools are more elongated than the LCT, but their current weight falls within the range of variation recorded for the LCT found at the T69 Complex. Trend lines and grey bands indicate the linear regression method and the 90% confidence interval, respectively (a–d), and the ellipses denote the 90% confidence interval (e,f).

Six tools made on more than 2-tonne mammal bones show a recurrent modification pattern to produce a particular shape (Fig. 3 and Extended Data Figs. 7 and 9). With an average of 16.8 removals per specimen, they feature one crescent and one pointed end, coupled with a large invasive notch produced by contiguous removals in the mesial part of the object. Most removal scars making the notch are present on the medullar surface. The pointed end of these tools systematically corresponds to the robust mid-portion of the diaphysis, and the rounded end to the metaphysis. The large notch may have facilitated the prehension of the tool while preserving its sturdy shape and heavy weight.

a, Elephant humerus (accession number T79L10-9047). b, Hippopotamus femur (accession number T79L10-18461). Scale bars, 5 cm. See also Extended Data Fig. 7 and Supplementary Videos 6 and 7.

A function as heavy-duty tools for the larger bone artefacts is suggested by comparison with LCT and smaller retouched lithics from the T69 Complex assemblage. The notched bone tools are larger, more elongated and more intensively shaped than the stone tools—LCT average of 10.1 flake scars per artefact—whereas their current weight falls within the range of recorded variation for LCT found at the site (Fig. 2e,f). Furthermore, distal fracture patterns on some of the specimens evoke their use in percussive and compressive activities38,39,40,41 (Methods; Extended Data Fig. 11).

In summary, to produce bone artefacts at the T69 Complex, hominins selected bones from large mammals and preferentially elephant. Precise anatomical knowledge and understanding of bone morphology and structure are suggested by preference given to thick limb bones as tool blanks. Excellent understanding of bone fracture mechanics is shown by the preferential use of large mammal fresh bones and the application of recurrent flaking procedures. Mental templates are suggested by the production of morphologically similar, elongated, pointed and notched bone tools.

Implications for early bone tool technology

Systematic bone tool production from a single horizon dated to 1.5 Ma at the T69 Complex prompts a reconsideration of the emergence and evolution of bone technology among early hominins. Previous evidence on bone tool production in the Early Stone Age concerned either used unmodified bone fragments3,11,12,13, isolated discoveries of possible knapped tools preventing firm conclusions on early hominin behaviours4,14,15,16,17, or bone tools shaped by knapping only occurring after 500 ka5,6,9,18,19,20,21,42. By contrast, the T69 Complex contains, within the same archaeological assemblage, a set of bone tools that share consistent technological features and signal to the existence of a patterned behaviour.

The T69 Complex bone tools demonstrate that, 1 million years before the production of fully formatted bone bifaces, East African hominins complexified their technology by systematically integrating large, knapped bone tools into it. Such integration occurred at a pivotal time in the evolution of African cultural adaptations—namely, the transition between the late Oldowan and the early Acheulean—and may have had a profound effect on the complexification of behavioural repertoires observed in the latter period43, including enhancements in cognition and mental templates44, artefact curation and raw material procurement45. This innovation took place at a moment in which large bifacial stone tools had a minor role in their technical systems46 and had yet to acquire the large size, refined technology and typical symmetrical morphology known for bifaces from subsequent Acheulean assemblages47. Particularly at butchery sites of large mammals where suitable raw material was readily available, large heavy bone tools may have fulfilled functions that were later achieved by large bifacial stone tools, which afforded both heavy weight and effective cutting edges. This hypothesis may explain why after the advent of systematic lithic handaxe production, heavy-duty bone tools such as those found at the T69 Complex, potentially less efficient in cutting tasks, may have become rare. In this view, Middle Pleistocene Acheulean bone handaxes5 could be interpreted as a local transfer to bone of a knapping technology in contexts where scarce availability of optimal lithic raw materials hindered the production of stone LCT.

The alternative scenarios entail that bone technologies appeared and disappeared across more than 1 million years, or were more common in the Early Stone Age than previously thought. In both cases, evidence of such technology is yet to be reported adequately. Preservation bias against organic materials and the limited availability of studies targeting the identification of knapped bone may be masking the widespread and systematic use of osseous technologies, until now thought to appear much later in our evolutionary history. Future research needs to investigate whether similar bone tools were already produced in earlier times, persisted during the Acheulean and eventually evolved into Middle Pleistocene bone bifaces similar in shape, size and technology to their stone counterparts.

Methods

Site context

Location and age

The T69 Complex (WGS84 UTM Zone 36S, x = 760990; y = 9669250) is located in the Frida Leakey Korongo (FLK) West outcrop, within the Main Gorge at Olduvai Gorge, in northern Tanzania. Excavations were conducted annually through eight field seasons between 2015 and 2022. Seven trenches (T69, T71, T74, T75, T77, T78 and T79) were dug at the site, of which three (T71, T74 and T75) yielded no archaeological materials (T71 was placed above and T74–T75 below the fossil-bearing horizons). Separate names were given to the trenches as test pits progressed around the main outcrop, but eventually they were all linked up into one single excavation area (Supplementary Video 1) named T69 Complex, after the first trench we dug at the FLK West locality.

Stratigraphically, the site is positioned in Olduvai Bed II, which overlays Bed I and is capped by Bed III (Extended Data Fig. 1e). The top of Bed I (Tuff IF) is dated to 1.803 ± 0.002 Ma48, whereas the base of Bed III is estimated at 1.14 ± 0.05 Ma49. Within Bed II, the T69 Complex is placed within a sandstone bed in the Tuff IIC stratigraphic interval50 that marks the transition between Middle and Upper Bed II14, and sits 7 m above the Bird Print Tuff and 4 m below Tuff IID35. A tuff located 20 cm below the Bird Print Tuff51 has been dated at 1.664 ± 0.019 Ma52, and an average age of 1.339 ± 0.024 Ma has been estimated for Tuff IID53. The bone tool level in the T69 Complex has been dated at 1.48 ± 0.2 (1σ) Ma using direct cosmogenic nuclide isochron burial dating35, which is consistent with the constraining ages available for Beds I, II and III (Extended Data Fig. 1e).

During the Tuff IIC interval, the Olduvai perennial palaeolake was constrained by the graben between the Fifth and FLK faults. The FLK locality was positioned in the southeastern lake-margin zone, with drainage inputs towards the north-northeast50. The T69 Complex deposits are dominated by the fluvial and lacustrine processes occurring at the eastern margin of the Bed II palaeolake50. The lower interval consists of alluvial massive sands and silty decantation facies (Extended Data Fig. 1d). These deposits were partially eroded by water flows, which led to the sedimentation of the sandstone bed containing the bone tool horizon. This sandstone has a sheet-like geometry and contains mainly tuffaceous facies with a massive or poorly bedded structure. The sandstone bed includes local lenses of augitic cross-laminated facies more abundant towards the base, and discontinuous patches of cemented very fine sandstone towards the top. Thin sections of the sandstone indicate a clay matrix and subrounded to rounded grains, from very coarse to fine in size, that locally include claystone rip-up subrounded clasts (Extended Data Fig. 1f). These sedimentological features suggest that cross-laminated facies were generated by local phases of traction and sedimentation under low regime flow conditions, whereas predominant massive or weakly bedded facies were formed by relatively rapid deposition of suspended load during decreasing flood. The sandy facies were buried by progradation of lacustrine brown clays (Extended Data Fig. 1d).

Excavation and sample preparation

Sedimentary units with no archaeological remains overburdening fossiliferous beds, which in some parts of the outcrop were more than 6 m thick, were removed manually with larger picks. Excavation of archaeological units initiated with small picks, and when remains were found, these were uncovered sequentially with screwdrivers, dental tools and wooden sticks. Each item found in situ, regardless of its size, was given a unique ID, positioned three-dimensionally with a total station, and recorded following the protocols outlined by de la Torre et al.54. Azimuth (dip direction, 0–360°) and dip angle (0–90°) of the major axis of suitable elongated items55 were recorded with compass and clinometer during the excavation process. All sediment collected from the archaeological units was dry-screened with 2-mm-mesh sieves. All items with an individual ID were hand-labelled, and a QR code was attached and added to a geographical information system that integrates all archaeological information for the FLK site.

Following conservation protocols detailed elsewhere56, some bone tools were stabilized by temporary consolidation with cyclododecane (a cyclic alkane hydrocarbon) before being lifted from the excavation. Solutions of paraloid B-72 (ethyl methacrylate–methyl acrylate co-polymer) or B-44 (methylmethacrylate–ethylacrylate) on acetone were also used. Mechanical removal of sedimentary accretions avoided contact with bone surfaces. When necessary, excessive consolidant was removed, breaks aligned and further consolidation carried out. Gaps or cracks that undermined structural condition of fossils were filled with B-44 or B-72 mixed with acetone and microscopic glass spheres.

Site formation

The T69 Complex bone horizon spans an average thickness of approximately 50 cm and was excavated across a surface of 295 m2 (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Video 2). Using ArcGIS Pro (v3.3), the horizontal distribution pattern was tested through an average nearest neighbour analysis that compared the actual distance between items to a hypothetical random sample57. The complete assemblage and the lithic and fossil assemblages showed a significantly clustered distribution (P = 0.000; Extended Data Fig. 3-1), whereas the bone tools were randomly distributed across the clusters (P = 0.6785).

Orientation58,59 and fabric analyses55,60 were conducted using Oriana software (v3.13) to investigate potential rearrangements of the assemblage. Orientation angular histograms show a circular-shaped distribution (Extended Data Fig. 3-2a), which becomes more homogeneous when axial values are projected (Extended Data Fig. 3-2b). When considering orientation as axial data (0–180°), statistical tests do not allow rejecting the null hypothesis of uniformity. By contrast, all azimuthal data statistical tests reject the uniform distribution against unimodal and plurimodal distributions, indicating a preferential orientation pattern with a mean vector at N22° E (see statistical results in table 1 in Supplementary Data 1). Stereographic projection of azimuth and dip values showed that most of the data concentrated around the external area and dominated by low dip angles (Extended Data Fig. 3-2c). Fabrics indicate a gridle or planar shape (Extended Data Fig. 3-2d,e), with eigenvector 1 pointing towards N27° E and thus coinciding with the mean vector direction (table 2 in Supplementary Data 1).

In summary, horizontal distribution patterns do not indicate a differential distribution between fossils and lithics, with both groups appearing together in clusters and bone tools scattered randomly across the excavation surface. The planar or girdle fabric with low dip angles suggests that archaeological items were accumulated on a subhorizontal surface and did not experience post-depositional vertical dispersion. Nonetheless, azimuthal data in the horizontal dimension indicate a notable influence of the dip direction, characterized by a mean vector that coincides with the north-northeast palaeo-drainage trend estimated by Hay50 in the lake-margin zone near the FLK locality. This suggests that the archaeological assemblage may have experienced some rearrangements by the alluvial flows depositing the sandstone bed. Given the generally excellent preservation of the archaeological items, the sheer abundance of less than 2 cm lithics, the sedimentological features of the sandstone bed (see the ‘Location and age’ section), and the orientated but scarcely clustered angular pattern, this gentle reorganization would be produced by low-energy flood-sheets with a poor sorting capacity, in which the item direction was determined by the depositional surface.

Faunal assemblage

The T69 Complex fossil assemblage (n = 22,832; bones of 2 cm or more = 45.3%; bones of less than 2 cm = 54.7%) contains abundant mammal (more than 11,627), reptile (n = 1,453), fish (n = 1,084) and bird (n = 286) specimens. Mammal bones of 2 cm or more (n = 8,930) were sampled for full zooarchaeological analysis following refs. 56,61,62. This zooarchaeological control sample (ZCS; n = 2,075) included (1) all items identified as bone tools, (2) all proboscidean fossils (given their relevance among the bone tool assemblage, the entire T69 Complex fossil collection was inspected to ensure all elephant specimens were analysed), and (3) a randomly selected sample from all other 2 cm or more mammal bone specimens. Whenever possible, the taxa and skeletal element were recorded. Otherwise, the specimens were attributed to a mammal size class based on their cortical thickness following Bunn63. Fresh and weathered bone fractures were distinguished based on criteria available in the literature64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71.

The ZCS skeletal part profile is dominated by axial bones (ribs and vertebrae), followed by appendicular elements (particularly tibia, femur, humerus and unidentifiable long bone fragments; tables 3 and 4 in Supplementary Data 1). Taxonomically, the ZCS assemblage is dominated by Bovidae (n = 691; 33.3%) and Hippopotamidae (n = 233; 11.2%), with considerably lower proportions of Equidae (n = 49; 2.3%) and Elephantidae (n = 22; 1.1%), and residual presence of other taxa such as Rhinocerotidae (n = 8; 0.4%), Suidae (n = 7; 0.3%) and others (n = 2; less than 0.1%; table 5 in Supplementary Data 1). The assemblage contains at least 16 different individuals from 10 distinct species (table 6 in Supplementary Data 1): Hippopotamus cf. gorgops (minimum number of individuals (MNI) = 4), Equus sp. (MNI = 2), Elephas cf. recki (MNI = 2), Diceros cf. bicornis (MNI = 2), Damaliscus cf. lunatus (MNI = 1), Connochaetes aff. gentryi (MNI = 1), Eudorcas cf. thomsonii (MNI = 1), Hippotragus gigas (MNI = 1), Kobus sp. (MNI = 1) and Tragelaphus aff. imberbis (MNI = 1). Overall, taxonomic composition and animal size distribution (table 7 in Supplementary Data 1) of the T69 Complex site suggests similar ecological conditions to the modern-day Serengeti ecosystem, with open and seasonal grassland habitats dominated by large communities of size 2 and 3 bovids near rivers and at the margin of an alkaline lake that accommodated hippopotamids, fish and crocodilians72,73.

Cut marks (present in more than 5.5% of the ZCS specimens) and percussion marks (more than 3.1%) indicate that early humans butchered carcasses at the site (tables 8 and 9 in Supplementary Data 1). According to the tooth-marked bone proportion (more than 2.4%), carnivores had a lesser role in the formation of the assemblage (table 10 in Supplementary Data 1). A short period of subaerial exposure is documented in 39.8% of specimens, although stage 2 (ref. 74) bones dominate the sample and more weathered bones are also present (table 11 in Supplementary Data 1). All these taphonomic signatures indicate separate assemblage formation episodes and are consistent with the alluvial dynamics that characterize the T69 Complex depositional environment.

Site function

Taxa represented, skeletal part profiles and taphonomic patterns indicate that hominins occupied a floodplain environment where they accessed relatively complete carcasses of hippopotamus. Other mammal body parts that show anthropogenic modifications—including bovids (cut-marked bones) and elephants (flaked bones)—were potentially transported by hominins to the site. Hominins also imported large quantities of quartzite from the nearby hill of Naibor Soit50 to produce stone tools. The input of other biotic as well as abiotic agents to the formation of the assemblage is attested by the presence of tooth-marked bones—indicating carnivore action—birds, reptiles and fish—unrelated to the formation of the anthropogenic assemblage—and the sedimentary evidence—pointing at gentle rearrangements of parts of the deposit.

The large size of both the stone tool and bone assemblages suggests that hominins visited the area repeatedly, probably attracted by the availability of dead hippopotamus. Exploitation of hippopotamus carcasses was not limited to meat procurement, but also to the production of bone tools. Cut marks produced by lithics clearly indicate that stone tools imported from Naibor Soit had a role in the butchery activities, but we argue that hominins were also importing bone raw materials; elephant fossils are rare in the T69 Complex faunal composition, whereas they are overrepresented in the bone tool assemblage. We hypothesize that bone-tool makers accessed elephant limbs elsewhere and shaped large diaphyseal fragments that were then imported to the T69 Complex and used in percussive and compressive activities, potentially related to butchery of the hippopotamus carcasses that attracted hominins to the area.

Bone tools

Taphonomy

Bone tools (n = 27) with most conspicuous technological features were recognized onsite during the excavation process (Supplementary Video 2), whereas others were identified during the inspection of the entire sample of mammal bones of 2 cm or longer. Each specimen was first examined with a magnifying glass with incident light. Anthropogenic modifications were distinguished from natural modifications based on published criteria41,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85, with a particular attention on the natural and anthropogenic processes that could produce flaking scars on faunal remains, such as trampling86,87,88, carnivore alterations36,37,83,89,90 and marrow extraction4,9,91,92,93,94,95 (see below and Supplementary Data 3).

Bone tool analysis and comparison with archaeological and experimental samples

The archaeological material considered in the present study comprised: (1) the 27 bone specimens bearing features, that is, flake scars, impact and morphology, that led us to consider them as bone tools (henceforth, BTS; Figs. 1 and 3 and Extended Data Figs. 6–10). (2) A sample of 4,507 long bone fragments from the same excavation (henceforth, random control sample (RCS)). The RCS was selected to verify whether the bone tools stood out morphologically when compared with the rest of the fauna or instead represented an extreme in size variation, that is, in maximum length, width and thickness of the bone fragments. (3) A subsample of 250 long bone fragments from RCS (henceforth, random control subsample (RCSS)). The RCSS was selected to verify whether the number of flake removal scars observed on the BTS stood out from other specimens in the faunal assemblage or instead represented an extreme in variation.

To establish whether marrow extraction activities could have produced a flaking pattern akin to that observed on the RCSS and BTS, we compared the T69 Complex specimens with two published experimental samples of large mammal long bones fractured to expose marrow. The first, henceforth, experimental sample 1 (ES1), consisted of nine elephant long bones fractured by knapping that produced 107 diaphyseal fragments4. The second, ES2, derives from the fracturing of six horse long bones by knapping, which resulted in 33 diaphyseal fragments and 284 flakes and splinters9. The maximum length, width, thickness and cortical thickness of the specimens included in BTS, ES1 and ES2 were collected using a digital calliper. The following variables were recorded for specimens with flake removal scars: number of scars, the location of each scar (cortical or medullar surface, distal, proximal, right or left lateral edge), their arrangement (isolated, contiguous or series of contiguous flakes) and the breadth of each scar. The contiguous category includes both adjacent and overlapping flake removal scars. Series of contiguous flake scars imply two or more groups of contiguous scars separated by an unmodified edge. The breadth of the flake removal scars was compared with the cortical thickness of the diaphyseal fragment and with the shaft fragment size index, that is, the product of the maximum length and width (in centimetres) divided by two4, to detect anomalously invasive flake removal scars on BTS compared with those recorded for the ES1 and ES2 specimens.

Recurrent patterns in the anthropogenic modification of bone fragments were sought in the frequency, size and arrangement of flake removal scars as well as on fractures resulting from potential use. Technological features were described following conventions proposed by Inizan et al.96 and adapted to bone tools analysis by Pante et al.16. Size comparison was done between the heavy-duty bone tools, that is, a subsample of the BTS, and the lithic LCT and retouched flakes found in the T69 Complex assemblage. Finally, the weight of the heavy-duty bone tools and lithic LCT was also compared.

All bone tools were photographed with a Nikon D7500 camera (Nikon DX 18–140 mm 1:3.5–5.6 and Nikon N 105 mm 1:2.8 lenses), and 3D scanned with an Artec Space Spider 3D scanner. Relevant bone surface modifications were analysed with a Leica DVM6 digital microscope (Planapo FOV 12.55 and 43.75 objectives, up to ×675). The quantitative analyses and graphs were done in R-CRAN (v4.4.1)97.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses