Targeting fucosyltransferase FUT8 as a prospective therapeutic approach for DLBCL

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is globally recognized as the most aggressive subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It is classified into two major molecular subtypes based on gene expression profiling: activated B cell-like (ABC) and germinal center B cell-like (GCB) DLBCL [1]. Crucially, DLBCL genetic subtypes vary in pathogenesis, phenotypic characteristics, oncogenic survival pathways, and treatment responses [2, 3]. The standard first-line chemotherapy for DLBCL is R-CHOP, consisting of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone [4]. Despite high objective response rates (ORRs) to R-CHOP, ~30% of treated patients inevitably develop relapsed/refractory (R/R) DLBCL, which continues to be the primary cause of mortality [5], highlighting the limits of standard cytotoxic therapy [6].

Natural products have demonstrated the ability to simultaneously impact multiple oncogenic signaling pathways by modulating the activity or expression of their molecular targets. They exhibit diverse effects on pathways involved in apoptotic cell death, cell proliferation, and metastasis. Additionally, they have the potential to enhance chemotherapy efficacy in cases of drug-resistant cancer [7]. The escalating expenses associated with traditional medications and the rising incidence of cancer have prompted researchers to investigate alternative approaches that are both cost-effective and environmentally sustainable [8]. In this regard, natural small-molecule compounds are highly advantageous as potent adjuvants in cancer therapy due to their lower toxicity and reduced side effects [9]. Previous studies have shown that natural products possess anticancer activity and selectivity of anti-cancer agents [10].

The plant kingdom is one of the most important sources of natural products. There is an extensive range of phytochemicals with therapeutic activity, including alkaloids, terpenes, essential oils, and flavonoids [11]. Over the past few decades, there has been extensive research conducted on phytochemicals due to their potential anticancer properties. The aim of these studies is to utilize them in cancer treatment approaches, including chemotherapy and targeted therapy [7]. Flavonoids, in particular, offer a diverse range of compounds that may be useful in cancer prevention and/or treatment [12]. Morus alba L. has been traditionally used in Asian countries as a medicinal herb, possesses anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activities [13]. Studies have shown that flavonoids are abundant in Morus alba L., especially in the root barks [14, 15]. Moreover, Morus alba L. root bark extract shows promising potential for anti-cancer effects [16,17,18,19]. Morusinol is a prenylated flavonoid derived from the root bark of Morus alba L. with a molecular weight of 438.5 Da [20]. Previous studies showed that Morusinol exhibits strong anti-cancer effects in various cancers through multiple mechanisms. For example, Morusinol induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in melanoma by inhibiting DNA damage [21]. Besides, Morusinol inhibited cell proliferation and induced autophagy in colorectal cancer through FOXO3a nuclear accumulation-mediated obstruction of cholesterol biosynthesis [22]. However, the anti-DLBCL activity of Morusinol has not yet been reported, and the mechanism of action is elusive.

Therefore, this study endeavors to elucidate the therapeutic efficacy of Morusinol in managing DLBCL, delineate its mechanism of action, and probe innovative combinational therapeutic strategies for this condition.

Materials and methods

Compounds

Morusinol (LEIMEITIAN MEDICINE, DS0101, Chendu, China), Chidamide (selleck, S8567, Houston, TX, USA), KPT-330 (selleck, S7252, Houston, TX, USA), Decitabine (selleck, S1200, Houston, TX, USA), and Ibrutinib (selleck, S2680, Houston, TX, USA).

Cell lines and culture

SU-DHL-8, SU-DHL-2, Farage, HBL-1, and OCI-Ly3 cells were cultured at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and in RPMI-1640 medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cell line authentication was performed by cell line characterization core using short tandem repeat profiling (Genetic Testing Biotechnology Corporation). All experiments were performed with mycoplasma-free cells.

Datasets and data deposition

GSE10846: The retrospective study included 181 clinical samples from CHOP-treated patients and 233 clinical samples from Rituximab-CHOP-treated patients. Gene expression profiling of DLBCL patient samples was performed to investigate, whether molecular gene expression signatures retain their prognostic significance in patients treated with chemotherapy plus Rituximab. GSE32918: A retrospective study of 172 patients, 140 treated with R-CHOP, 32 not treated with curative intent. Gene expression profiling was carried out for RNA extracted from Formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded biopsies for 172 patients with DLBCL using the Illumina DASL platform. Classification into GCB, ABC or Type-III subtypes was carried out revealing a significant relationship between subtype and survival. GEO accession numbers of RNA sequences: GSE229896, GSE242115, and GSE241007.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: F4/80 Antibody (1:200, Zenbio, Cat# 263101, Chengdu, China), CD206 Antibody (1:200, Affinity, Cat# DF4149, New Jersey, USA), CD86 Antibody (1:200, Affinity, Cat# DF6332, New Jersey, USA), CD163 Antibody (1:20, Biolegend, Cat# 326513, CA, USA), CD16 Antibody (1:20, Biolegend, Cat# 302005, CA, USA).

Viability and proliferation assays

DLBCL cells (2 × 104/cells/ml) were seeded into 96-well plates at a volume of 90 µl/well and then treated with 10 µl/well of Morusinol at different concentrations (0, 5, 10, and 50 μM) for 48 h. Cells were treated for an additional 24 and 72 h to explore the time dependence of the drug effects. At the time of the reaction, 10 µL of CCK-8 (Cell Counting Kit-8) was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C in the dark for 2 h. The final absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm with a microplate reader.

Western blotting

Cell total proteins were extracted using lysis buffer, then subjected to centrifugation at 4 °C at 12,000 × g for 5 min. Equal amounts of protein were loaded onto 10–12% SDS-PAGE for electrophoresis, then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, MA, USA). H3 Antibody (1:1000, Abclone, Cat# A2348, Wuhan, China), H3K9ac Antibody (1:1000, Abclone, Cat# A7255, Wuhan, China), H3K18ac Antibody (1:1000, Abclone, Cat# A7257, Wuhan, China), H3K27ac Antibody (1:1000, Abclone, Cat# A7253, Wuhan, China), HDAC5 Antibody (1:1000, Abclone, Cat# A7189, Wuhan, China), GAPDH Antibody (1:1000, Proteintech, Cat# 60004-1-Ig, Chi, USA), and FUT8 Antibody (1:1000, Proteintech, Cat# 66118-1-lg, Chi, USA) were used as primary antibodies. The membranes were exposed to respective secondary antibodies and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) immunoblotting detection reagent (Tanon, Shanghai, China).

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR assays

Total RNA of transfected cells was firstly extracted by TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Following reverse transcriptions of cDNA implemented using PrimeScript RT kit (Takara biomedical Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China), qRT-PCR was performed using the SYBR® Green master mix (Bio-Rad, USA) on an ABI7500 system (Foster City, CA, USA). The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was regarded as endogenous controls. Reaction cycles were as follows: 95 °C for 5 min, 95 °C for 30 s with 40 cycles, 60 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 5 min. All data were analyzed using 2−ΔΔCT method to quantify the relative expression of genes. Each sample was performed with three replicates and every experiment was repeated three times. The primer sequences and small interfering RNA sequences are described in Tables S5, and S6.

Drug affinity–responsive target stabilization assay (DARTS)

Cell lysates were incubated with or without morusinol for 30 min at room temperature, followed by proteinase K (1:50) treatment for 10 min. The lysates were finally denatured and subjected to western blotting analysis. The protective band was visualized by Coomassie bule staining and identified by Liquid Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer (LC-MS).

Cellular protein thermal shift assay (CETSA)

In summary, cells were treated with dimethylsulfoxide as control or Morusinol (IC50) for 12 h. After treatment, the cells were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and the suspension was equally divided into five parts. Each part was then heated to 44, 46, 48, 50, and 52 °C for 3 min, followed by cooling at room temperature for 3 min. Subsequently, the cells underwent three freeze-thaw cycles using liquid nitrogen for lysis. The resulting lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatants were analyzed by western blotting.

Immunofluorescence

Immerse the DLBCL tumor tissue paraffin sections in xylene for 5 min, repeating twice to remove the paraffin completely. Then sequentially immerse the sections in anhydrous ethanol, 95% ethanol, 85% ethanol, 75% ethanol, 65% ethanol, and deionized water for 5 min each to remove xylene. Perform antigen retrieval by placing the dewaxed sections in diluted 1× citrate solution, heating the buffer to boiling, and allowing the buffer to cool to room temperature. Block the sections or coverslips with 5% BSA solution at room temperature for 1 h to block all non-specific binding. Dilute the primary antibody for the target protein in 5% BSA solution to the appropriate concentration and incubate the specimen at 4 °C overnight. Wash with TBST three times, 5 min each. Dilute the corresponding secondary antibody in TBST to the appropriate concentration and incubate at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. Wash with TBST three times, 5 min each. Stain the nuclei with DAPI at room temperature for 5 min. Wash with TBST three times, 5 min each. Drop 5 μL of anti-fade mounting medium onto the slide, and gently place a coverslip on top to avoid bubbles. Store the slide at 4 °C in the dark. After the mounting medium has dried, examine the slide using a laser-scanning confocal microscope.

In vivo tumor xenograft model

NOD-Scid mice and Nude mice were acquired from Gempharmatech Company. The NOD-Scid were injected with SU-DHL-2 cell line in 50% Matrigel subcutaneously on the left flank and were randomly divided into four groups without blinding (n = 5 per group) receiving daily treatments: (1) control group (PBS); (2) chidamide group (5 mg/kg); (3) Morusinol group (30 mg/kg); (4) combination group (3 mg/kg chidamide and 24 mg/kg Morusinol).

The Nude mice were injected with YAC-1 cell line and were randomly divided into 2 groups without blinding (n = 5 per group): (1) control group (PBS); (2) Morusinol group (30 mg/kg). Tumor size and mouse body weight were measured every 2 days to monitor treatment effectiveness. Tumor volume was calculated using the following formula: tumor volume (mm3) = (smallest diameter2 × largest diameter)/2. The research was conducted in accordance with the internationally accepted principles for laboratory animal use. The Soochow University Animal Ethics approved the experiment (Approval No.: 202207A0710).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8, with data presented as means ± standard deviation (SD). Two-tailed Student’s t-test determined intergroup significance, while one-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA assessed significance for multiple comparisons. The prognostic value of FUT8 expression levels was assessed with Kaplan–Meier analysis by using the log-rank test. Statistical significance was evaluated using SPSS v22.0, and ImageJ software quantified cells positive for immunohistochemical staining. P < 0.05 suggests a statistically significant difference.

Results

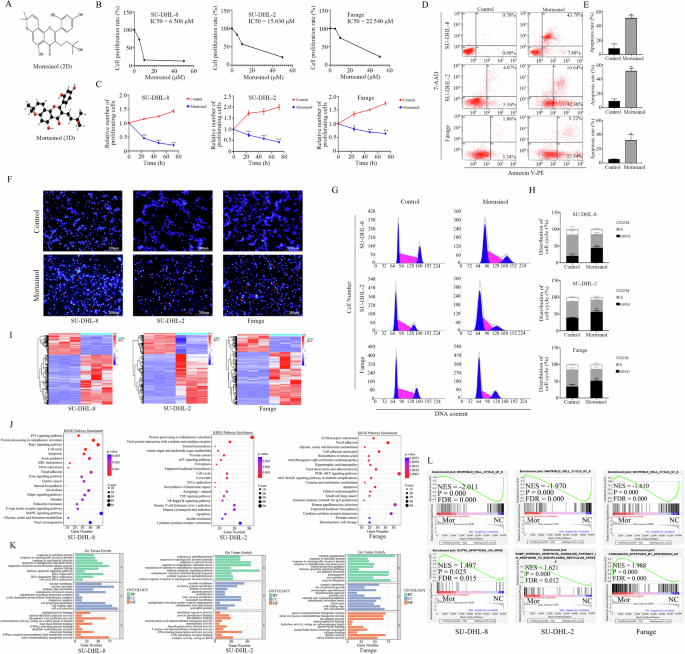

Morusinol exerts antitumor effects on DLBCL

DLBCL is a disease marked by clinical and genetic diversity, categorized into two primary subtypes: activated B-cell (ABC) and germinal center B-cell (GCB), distinguished by their gene expression profiles [2]. For the investigation of Morusinol’s effects on DLBCL, this study focused on one ABC DLBCL cell line (SU-DHL-2) and two GCB DLBCL cell lines (SU-DHL-8, Farage). Cells were treated with escalating concentrations of Morusinol (0, 5, 10, and 50 μM) for 48 h, and the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values were determined as 6.508 μM for SU-DHL-8, 15.030 μM for SU-DHL-2, and 22.540 μM for Farage, respectively (Fig. 1B). Morusinol exerted significant inhibitory effects on these DLBCL cell lines (Fig. 1C). Notably, the IC50 values varied considerably among three cell lines and did not correlate with the ABC and GCB subtypes. 7-AAD/Annexin V-PE double staining analysis revealed an increased proportion of apoptotic DLBCL cells after Morusinol treatment (Fig. 1D, E). Similar results were observed by Hoechst 33258 staining (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 1G, H, treatment with Morusinol caused G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in DLBCL cells.

A Chemical structure and interactive chemical structure of Morusinol. B IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) values of DLBCL cells (SU-DHL-8, SU-DHL-2, and Farage) treated with Morusinol at the indicated concentrations for 48 h. C The proliferation capacity of DLBCL cells (SU-DHL-8, SU-DHL-2, and Farage) treated with Morusinol (IC50) at the indicated times. D SU-DHL-8, SU-DHL-2, and Farage cells were treated with Morusinol (IC50) for 48 h, double stained with 7-AAD and Annexin V-PE, and analyzed by flow cytometry. E Percentages of apoptotic cells are shown in the statistical graph. F Representative morphological images of Morusinol-treated DLBCL cells after Hoechst 33258 staining. G SU-DHL-8, SU-DHL-2, and Farage cells were treated with Morusinol (IC50) for 48 h, stained with PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry. H Percentages of G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases in the cell cycle are shown in the statistical graph. I Heatmap of differentially expressed genes between groups of DLBCL cells. J, K The results of KEGG and GO mapping. L Representative GSEA plots indicated the enrichment of genes involved in negative regulation of CELL CYCLE signaling pathway and positive regulation of APOPTOSIS signaling pathway among the transcripts in the Morusinol-treated group in DLBCL cell lines. The enriched pathway was statistically significant when FDR < 0.25 and P < 0.05. All values represent the mean ± SD of three sets of experimental data. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001.

To comprehensively assess the impact of Morusinol on DLBCL cells, we conducted whole transcriptome analysis (RNA sequencing, RNAseq) on three DLBCL cells treated with either vehicle or Morusinol (Fig. 1I). Further analysis using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis, Gene Ontology (GO) functional annotations, and GSEA demonstrated that genes affected by Morusinol were linked to crucial cellular processes, including the cell cycle and apoptosis signaling pathways, across all three DLBCL cells (Fig. 1J–L, Tables S1, S2). Additionally, Morusinol impacted distinct significant pathways in each cell line; it influenced Hippo, MAPK, Rap1 signaling pathways in SU-DHL-8, TNF, and NF-κB signaling pathway in SU-DHL-2, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in Farage.

The above results demonstrated the significant inhibitory effects of Morusinol on DLBCL cells and its influence on various essential biological processes.

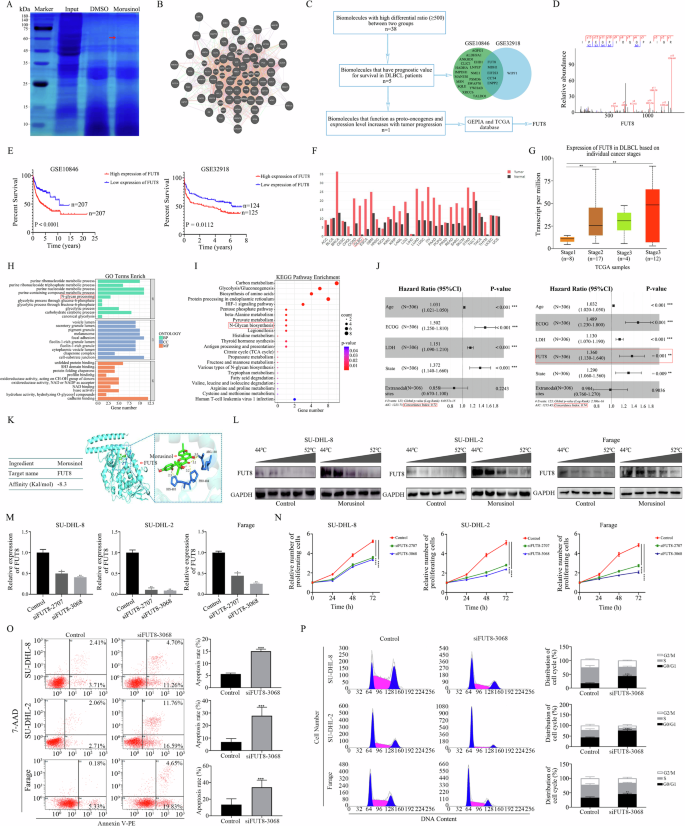

FUT8 is the target of Morusinol in DLBCL

Drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) is a technique for discovering targets, notably effective in identifying small molecule targets without necessitating structural modifications [23]. Thereby, DARTS and Liquid Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer (LC-MS) were applied to determine the potential target of Morusinol. As shown in Fig. 2A, compared with the vehicle-treated group, Morusinol-treated samples showed a band with enhanced intensity between 60 and 75 kD, suggesting that these proteins could bind to Morusinol. The band was subsequently analyzed by LC-MS, resulting in the identification of 60 proteins (Fig. 2B, Table S3). Among these proteins, 38 exhibited a high Mor/DMSO Ratio, indicating that they are potentially more viable targets for Morusinol (Table S3). Protein interaction analysis was then conducted using the Genemania database (Fig. 2B).

A Coomassie bule of the gel after SDS-PAGE of the potential Morusinol binding proteins. Specific bands were excised and analyzed through Liquid Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer (LC-MS). The red arrow indicates gel band unique to Morusinol. The unique gel band was sent for LC-MS protein detection. B Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network derived from the results of differential protein banding analysis using LC-MS. C The process of drug target protein screening. D Single peptide-based protein identification of FUT8. E The survival curve of the DLBCL patients based on FUT8 expression in the GSE10846 and GSE32918. F The expression of FUT8 in a variety of malignancies from the GEPIA database. G The expression of FUT8 in DLBCL cells based on individual tumor stages. H, I The results of GO and KEGG mapping. J C-index values of NCCN-IPI plus FUT8 model and NCCN-IPI model in multiple regression analysis. K The ability of Morusinol to bind to the FUT8 ligand-binding domain by molecular docking. L Cellular thermal shift assay showing FUT8 target engagement by Morusinol in DLBCL cells. DLBCL cells were incubated with Morusinol for 12 h, and cellular thermal shift assay was carried out. M The expression level of FUT8 was detected by qPCR. N CCK-8 assay was performed to detect the cell proliferation after FUT8 interference. O SU-DHL-8, SU-DHL-2, and Farage cells were transfected with siFUT8-3068 for 48 h, double stained with 7-AAD and Annexin V-PE, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of apoptotic cells are shown in the statistical graph. P SU-DHL-8, SU-DHL-2, and Farage cells were transfected with siFUT8-3068 for 48 h, stained with PI, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Percentages of G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases in the cell cycle are shown in the statistical graph. All data are shown as the means ± SD based on triplicate measures. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

To identify the crucial target of Morusinol, we conducted a two-round screening process consecutively, as illustrated in Fig. 2C. The identified 38 proteins mentioned above underwent survival analysis to ascertain their prognostic significance in DLBCL. Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed that five genes exhibited a consistent association with both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in two datasets (Figs. 2E, and S1–4). These five genes, including FUT8, displayed higher expression levels in DLBCL patients compared to healthy donors (Figs. 2F, and S5). Additionally, among these five genes, only FUT8 expression exhibited a progressive increase from stage 1 to stage 4 in DLBCL patients (Figs. 2G, and S6). FUT8 expression was higher in the ABC subtype of DLBCL, which is associated with a poorer prognosis, compared to the GCB subtype, which is linked to a relatively better prognosis (Fig. S7). The above results suggested that FUT8 may be the crucial target of Morusinol in DLBCL.

FUT8, known as α1,6-fucosyltransferase, is an enzyme involved in the process of protein glycosylation, specifically in adding fucose molecules to N-linked glycans. Its involvement in cancer has been extensively studied, particularly in relation to tumor progression, metastasis and immune evasion [24]. Besides, KEGG and Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis were performed on the proteins identified by LC-MS, and N-glycan biosynthesis was enriched (Fig. 2H, I). Understanding the significance of FUT8 in DLBCL might uncover a new therapeutic target for this disease. We furtherly employed Cox survival regression to simultaneously incorporate all the clinical variables captured by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network-International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) and FUT8 expression. Univariate and multivariate analysis revealed that the expression level of FUT8 might act as an independent prognostic factor for DLBCL patients (Fig. 2J, Table S4). Moreover, the integration of the FUT8 signature with NCCN-IPI demonstrated superior predictive capability for overall survival (OS) compared to utilizing NCCN-IPI alone (Fig. 2J).

The secondary spectrum of FUT8 further confirmed the reliability of the drug target (Fig. 2D). In the context of molecular docking, an affinity value of –8.3 Kal/mol indicated a highly favorable interaction between Morusinol and FUT8, suggesting that Morusinol is likely to bind tightly and specifically to the active site or binding pocket of the FUT8 protein (Fig. 2K). Furthermore, the Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) provided additional evidence for the interaction between Morusinol and FUT8. In DMSO-treated cells, FUT8 started to degrade at 46 °C and almost disappeared at 48 °C. However, in Morusinol-treated cells, FUT8 degradation was delayed, with the protein starting to degrade at 48 °C and disappearing at 52 °C (Figs. 2L, S8). These results strongly indicated that Morusinol interacted with FUT8 and stabilizes its structure, making the protein less susceptible to heat-induced denaturation. This stabilization of FUT8 by Morusinol was a clear indication of potential target engagement.

To delve deeper into the role of FUT8 in DLBCL, we conducted loss-of-function analysis by transfecting siRNAs targeting FUT8 into DLBCL cells (Fig. 2M). Interference of FUT8 suppressed cell proliferation, induced apoptosis and caused G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in DLBCL cells (Fig. 2N–P).

Collectively, these results suggested that FUT8 played an oncogenic role in DLBCL, and the targeting of FUT8 by Morusinol held promise as a potential therapeutic approach for the treatment of DLBCL.

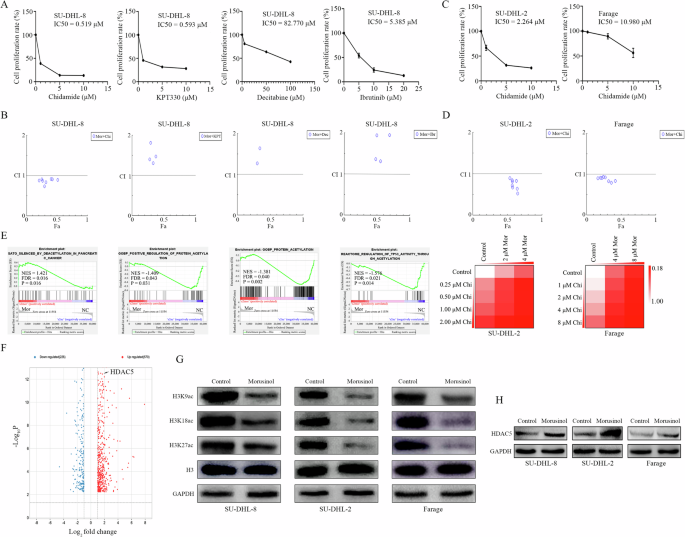

Synergistic cytotoxicity of Morusinol and chidamide in DLBCL

Monotherapies in cancer have demonstrated limited clinical efficacy, while combinatorial therapies with two or more targeted drugs hold promise for enhancing treatment outcome [25]. We proceeded to investigate the synergistic effects of Morusinol in combination with four commonly used hematological disorder drugs (chidamide, KPT-330, decitabine, and ibrutinib), in both preclinical and clinical settings. IC50 values of the drugs on SU-DHL-8 cells were quantified as 0.519 µM, 0.593 µM, 82.770 µM, and 5.385 µM, respectively (Fig. 3A). Treating SU-DHL-8 cells with Morusinol and each agent separately, we observed potent synergistic cytotoxicity with the combination of Morusinol and chidamide, while no synergy was evident with the other three drugs (Figs. 3B, S9, S10). Our investigation was further extended to other two DLBCL cells, SU-DHL-2 and Farage, where chidamide’s IC50 values were determined to be 2.264 µM and 10.980 µM, respectively (Fig. 3C). Encouragingly, synergistic cytotoxicity was also evident when Morusinol was combined with chidamide in other DLBCL cell lines (Figs. 3D, S11).

A IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) values of SU-DHL-8 cell line after being treated with Chidamide, KPT330, Decitabine, and Ibrutinib at the indicated concentrations for 48 h. B CI (combination index) plots in SU-DHL-8 were calculated based on the Chou–Talalay equation using CompuSyn software. Each symbol designated the CI values for each Fa (fraction affected) at different dose points. C DLBCL cell lines (SU-DHL-2, and Farage) were treated with increasing concentrations of chidamide for 48 h and cell viability was measured by CCK8 assay. IC50 values in two cell lines are shown. D CI plots were calculated based on the Chou–Talalay equation using CompuSyn software. Each symbol designated the CI values for each Fa (fraction affected) at eight different dose points. Percentage of cells alive was expressed using heat maps. E Representative GSEA plots indicated the enrichment of genes involved in positive regulation of DEACETYLATION signaling pathway and negative regulation of ACETYLATION signaling pathway among the transcripts in Morusinol-treated group in SU-DHL-2 cell line. The enriched pathway was statistically significant when FDR < 0.25, P < 0.05. F Part of the differential expressed genes (|Log2FC| > 1, p < 0.05) after Morusinol treatment were shown in the volcano plot. HDAC5 is one of the upregulated genes (Log2FC = 1.70, p < 0.0001) by Morusinol treatment. G, H After 48 h of treatment with Morusinol (IC50), the protein extracts from the SU-DHL-8, SU-DHL-2, and Farage cells were analyzed by western blotting to determine the changes in the levels of H3K9ac, H3K18ac, H3K27ac, H3 and HDAC5 proteins.

Subsequently, we conducted RNA sequencing analysis and GSEA to uncover the underlying mechanism of synergy. GSEA analysis revealed a notable distinction in the expression patterns of genes related to DEACETYLATION and ACETYLATION signaling pathways, suggesting that Morusinol increased deacetylation levels while decreasing acetylation levels (Fig. 3E). The volcano plot revealed that HDAC5 (log2FC = 1.70, p < 0.001) was one of the significantly upregulated by Morusinol (Fig. 3F). Subsequent experiments validated that Morusinol effectively reduced histone acetylation levels and increased HDAC5 expression in DLBCL (Fig. 3G, H). Based on these findings, we proposed that the synergy between Morusinol and chidamide was rooted in a complementary pathway. Morusinol’s reduction of histone acetylation levels was a side effect, while chidamide, being a histone deacetylase inhibitor, reversed this effect, thereby enhancing the overall therapeutic outcome.

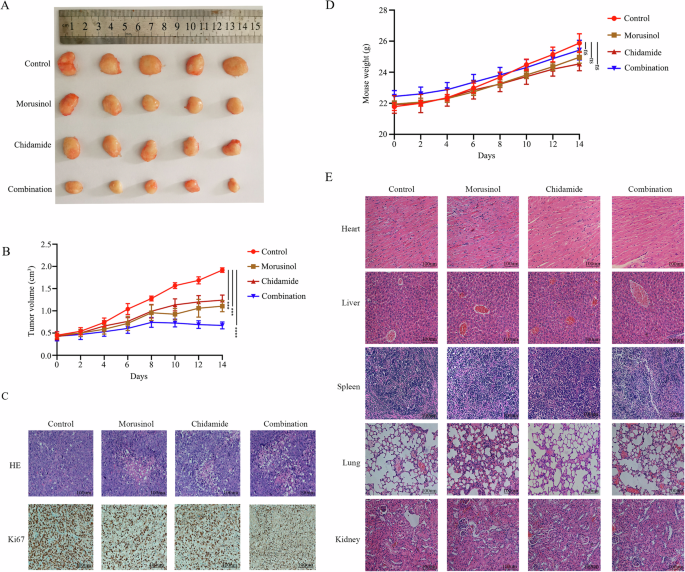

Synergistic effects of Morusinol and chidamide combination in reducing DLBCL burden in vivo

To assess the therapeutic potential of combining Morusinol and chidamide in DLBCL in vivo, we established DLBCL mice models. Tumor-bearing mice were treated with DMSO, Morusinol, chidamide or a combination of Morusinol and chidamide, respectively. Acute toxicity experiment in mice was conducted to confirm the safety of Morusinol (Fig. S12). Morusinol and chidamide individually inhibited tumor growth, while their combination exhibited significantly better inhibitory effects (Fig. 4A–C). Furthermore, an important aspect of any therapeutic approach is its safety profile. Moreover, we closely monitored the mice’s body weight to assess treatment safety. Encouragingly, there were no significant differences in body weight compared to the control group, indicating that the mice tolerated Morusinol well without experiencing any adverse effects (Fig. 4D). To assess potential toxicity, we conducted histological examinations of vital organs, including the heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney tissues. Gratifyingly, no toxicity or significant histological damage was observed in any of these organs in both the Morusinol-treated group and the Morusinol and chidamide combination-treated group (Fig. 4E). These results further supported the safety of the combination therapy.

A Tumor specimens photographed with a high-definition digital camera. B Tumor volume was measured every 2 days. C H&E and Ki67 staining of tumor tissues in the NOD-Scid mice (magnification: ×400). D The weight of the mice was recorded every 2 days. E H&E staining of heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney tissues in the NOD-Scid mice (original magnification: ×400); There were 5 mice in each group. ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001.

The above results suggested that the combination of Morusinol and chidamide holds promise as a synergistic therapeutic approach in reducing DLBCL burden.

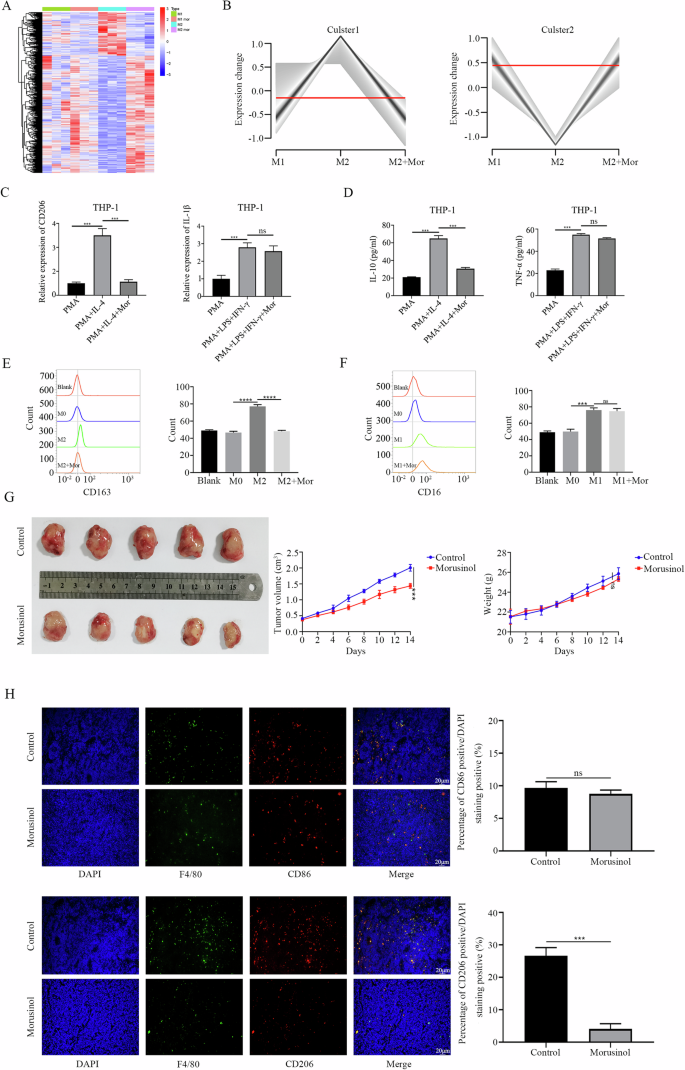

Morusinol efficiently inhibits M2-like polarization of macrophages in vitro and in vivo

In DLBCL, an increasing population of immune-suppressive M2 macrophages is associated with poor prognosis [26, 27]. THP-1 cells were first polarized into M0 macrophages by treatment with PMA, and then M1 and M2 macrophages was induced by treatment with LPS plus IFN-γ and IL-4, respectively. To investigate the effects of Morusinol on macrophage polarization, we conducted RNA sequencing, revealing significant changes in gene expression levels in M2 macrophages, while M1 macrophages remained relatively stable or showed slight changes in response to Morusinol (Fig. 5A). Simultaneously, the Mfuzz clustering analysis indicated a trend of Morusinol reversing macrophage polarization towards M2 phenotype (Fig. 5B). Subsequently, we conducted experiments to validate the above results. Subsequent experiments validated that Morusinol reduced the expression of M2 markers (CD206, IL-4, and CD163) in macrophages, indicating suppression of M2-like polarization. Conversely, there were no significant changes in M1 markers (IL-1β, TNF-α, CD16) (Fig. 5C–F).

A THP-1 cells were exposed to PMA (100 ng/mL) for 24 h, then M1 and M2 polarization was treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) plus IFN-γ (20 ng/mL) and IL-4 (20 ng/mL) respectively, with or without Morusinol (6.508μm/L) for 24 h. Heatmap of differentially expressed genes between groups of macrophages. B Mfuzz clustering analysis of macrophages. C Quantitative real-time PCR was performed to assess the mRNA levels of M1-marker and M2-marker genes. D–F Expressions of specific M1 and M2 signature proteins were assessed using ELISA assay and flow cytometry. G There were 5 mice in each group. Tumor specimens photographed with a high-definition digital camera. Tumor volume was measured every 2 days. The weights of the nude mice were recorded every 2 days. H The tumor tissues from a different group were double stained with the macrophage marker F4/80 and the M1-marker CD86/M2-marker CD206. The percentage of CD86+ and CD206+ cells was calculated as a ratio of red cells to DAPI blue cells. All values are shown as the means SD based on triplicate measures. ***P < 0.001.

For in vivo analysis, we utilized a syngeneic transplantation mouse model in nude mice, which retain innate immune cells, including macrophages. Morusinol demonstrated a significant inhibitory effect on tumor growth without affecting body weight compared to the control group (Fig. 5G). Further investigation into Morusinol’s inhibitory effect on tumors revealed a marked reduction in the proportion of CD206+ macrophages within tumor tissue, while the percentage of CD86+ macrophages remained relatively unchanged (Fig. 5H).

These results indicated that Morusinol’s inhibition of M2-like polarization of macrophages may hinder tumor-supportive conditions, leading to reduced tumor growth in DLBCL.

Discussion

Largely due to the absence of effective targeted treatment regimens, the five-year survival rate for patients with DLBCL is a meager 40% or less [28]. Thus, developing innovative agents to treat DLBCL, particularly derived from natural sources, is regarded as a crucial strategy. Through screening natural compound libraries, we have discovered Morusinol as a promising candidate to combat DLBCL. Morusinol has demonstrated significant anti-DLBCL activity by inhibiting cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, and causing cell cycle arrest.

The restricted utilization of natural products stems from an incomplete comprehension of their targets [29]. Utilizing DARTS and LC-MS analysis, coupled with subsequent functional screening, we present compelling evidence establishing FUT8 as the primary target of Morusinol. FUT8 is the exclusive fucosyltransferase responsible for core fucosylation, involving the α-1,6-linkage addition of fucose to the innermost N-acetyl glucosamine of N-glycans [30]. Fucosylation, a type of glycosylation, entails attaching a fucose residue to N-glycans, O-glycans, and glycolipids. This process can be categorized into terminal and core fucosylation, catalyzed by various fucosyltransferases (Fut). Notably, FUT8 stands as the sole Fut accountable for core-fucosylation on N-glycoproteins [31,32,33,34]. Studies underscore that fucosylation changes are associated with malignant progression, invasion, and metastasis across diverse cancer types, including, but not limited to, hepatocellular, gastric, pancreatic, prostate, and colorectal cancers [35,36,37,38,39]. Studies have revealed that FUT8 could be a potential therapeutic target for malignant tumors, such as colorectal cancer [40, 41]. Our findings highlight the substantial role of FUT8 in DLBCL proliferation, with its elevated expression correlating with adverse survival outcomes in DLBCL patients. Morusinol, identified as a FUT8 inhibitor, directly binds to the enzyme. This discovery holds significant implications in drug discovery and development, as it elucidates the intricate molecular interactions between Morusinol and its target, thereby suggesting its potential as a therapeutic agent.

Overexpression of HDACs in tumor cells may lead to proliferation and dedifferentiation. Conversely, the downregulation of HDACs can trigger various anti-tumor effects such as inducing cell cycle arrest, inhibiting proliferation, and inducing apoptosis [42]. Chidamide, a benzamide-class selective HDAC inhibitor developed in China, has been found to effectively enhance the acetylation of histone H3 [43, 44]. Our results demonstrated that the conjunction of Morusinol and chidamide exhibited synergistic cytotoxicity against three DLBCL cell lines, especially in the SU-DHL-2 cell line, as evidenced by predominantly <1.0 combination index (CI) values.

Macrophages present in various tissues undergo polarization in response to environmental changes, resulting in the formation of distinct subtypes such as M1 and M2 macrophages [45]. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) exhibit a dual role, contributing to both the elimination and the proliferation of tumor cells. Specifically, M2 macrophages exhibit a phenotype similar to TAMs and can promote tumor growth and metastasis, ultimately leading to a poorer prognosis for tumors. On the other hand, M1 macrophages are commonly recognized as tumor-suppressive macrophages, predominantly displaying anti-tumor and immune-enhancing properties [46]. This study highlighted the correlation between macrophages and the tumor-inhibiting impact of Morusinol, indicating that the inhibited accumulation of M2-like macrophages in DLBCLs may be the primary mechanism behind the anti-tumor effect of Morusinol.

In summary, the natural small-molecule, Morusinol, exhibits potent antitumor effects on DLBCL through the induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in vitro, as well as the reduction of tumor burden in vivo. The identification of FUT8 as the target protein that interacts with Morusinol provides insights into its mechanism of action. Moreover, the combination of Morusinol and chidamide presents a promising and synergistic therapeutic approach for effectively reducing the burden of DLBCL. In summary, Morusinol demonstrates significant potential as an anti-tumor agent for clinical applications in DLBCL management, offering the prospect of enhancing existing therapeutic strategies.

Responses