Targeting of TAMs: can we be more clever than cancer cells?

Introduction

Cancer,particularly its metastatic form, is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. According to World Health Organization data for 2019, cancer is the first or second leading cause of death in 112 countries under 70 years of age [1]. Cancer is an acute problem in both developed and developing countries due to the aging and growing populations, accelerated socioeconomic development and increased prevalence of associated risk factors (such as environmental pollution, chronic stress, and obesity). Worldwide, cancer is the leading cause of premature death and reduces life expectancy [2]. Currently, the treatment of solid tumors needs major improvement, despite significant progress in the development of immunotherapy approaches as well as the identification of a number of biomarkers, mostly genetic, that are useful for the personalization of conventional therapies [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Such principal improvement can be achieved if the potential of programming anticancer innate immunity, systemically or locally, is fully exploited.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are key innate immune cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME) due to their quantity (in some tumors, TAMs constitute more than 50% of the tumor mass) and multiple tumor-supporting functions that act at all stages of carcinogenesis: tumor initiation, progression, metastatic spread via the blood or lymphatic circulation, response to therapy, and post-therapeutic metastatic relapse [9,10,11].

The major population of TAMs originates from circulating monocytes recruited by tumors, and recent studies have demonstrated that monocytes in cancer patients differ in their subpopulational content, transcriptome and metabolome from monocytes in healthy donors; moreover, subpopulational, transcriptomic and metabolomic signatures are highly specific for distinct solid tumors [12,13,14,15,16].

Substantial progress has been made in the accumulation of published evidence on the correlations between specific TAM subtypes and the clinical characteristics and therapeutic resistance of patients with solid cancers, and a deep understanding of the mechanism of TAM-mediated tumor support has led to a new wave of interest in the therapeutic targeting of TAMs.

Our review summarizes the knowledge about TAM subtypes and their biomarkers that correlate with primary tumor growth, metastatic spread and therapy resistance in several human solid cancers, with a focus on cancers of primarily noninfectious origin. We present the state-of-the-art in our understanding of TAM functions and secreted mediators that accelerate tumor progression, highlighting epigenetic, transcriptional and metabolic mechanisms in TAMs that offer new molecular interactions and pathways for reprogramming of TAMs. We also highlight the principal recent discoveries of novel biomarkers that discriminate between tumor-supporting and tumor-inhibiting TAMs independent of the M1/M2 dichotomy. Finally, our review summarizes major approaches for therapeutic targeting of TAMs that have been or are currently in clinical trials and evaluates their credibility and prospects for clinical application.

Intratumor diversity of TAMs and their clinical significance in human cancers

The TAM phenotype reflects their specific role in different cancers. The correlations of distinct TAM subpopulations with primary tumor growth, lymphatic and hematogenous metastasis and treatment efficacy are specific for each type of cancer [9]. The major method originally applied for the identification of TAMs in human tumor tissue was immunohistochemistry (IHC) with anti-CD68 antibodies [17]. In the majority of studies, correlations of CD68 expression with the following clinicopathological parameters, histological grade, tumor size, TNM stage, lymph node status, and lymphovascular invasion, as well as with distant metastasis, recurrence and survival rates, were analyzed [9, 17]. Many studies have demonstrated that high infiltration of TAMs, as defined by CD68 expression, is associated with poor clinical outcomes in many cancers, including breast, lung, pancreatic, gastric, prostate, and ovarian cancers; hepatocellular carcinoma; melanoma; and glioblastoma [18] (Fig. 1). However, in contrast to other cancer types, the number of TAMs in colorectal cancer (CRC) is positively correlated with favorable outcomes, but the mechanism of this phenomenon remains unresolved. This observation was made in multiple international cohorts of patients with CRC: Swedish, Bulgarian, Japanese, Chinese, German, American, Greek, and others [19,20,21,22,23,24]. The number of CD68+ TAMs is decreased at advanced stages of CRC, in patients with regional LN metastases and distant metastases, and is associated with increased survival in CRC patients [19,20,21,22,23,24]. A recent study indicated that the association of high CD68+ TAM density with survival rate in patients with stage I-III CRC was dependent on tumoral T-cell density [25]. High TAM density was associated with a good prognosis in patients who also had high T-cell counts in tumors, while it was associated with an unfavorable prognosis in patients with low T-cell counts [25].

Clinical significance of TAMs. For the majority of TAM biomarkers, their correlation with unfavorable prognosis has been demonstrated for solid cancers. In contrast to other cancers, in colorectal cancer, CD68 (panmacrophage marker) is positively correlated with favorable patient prognosis. Individual TAM biomarkers are illustrated by different color coding. Filled macrophage icons are used as biomarkers for scavenger receptors. Сontoured macrophage icons are used as other TAM biomarkers. The orange background covers macrophage subtypes that correlate with a negative prognosis or with the inhibition of anticancer therapy efficacy. The blue background covers TAM subtypes that correlate with a favorable prognosis and TAMs that cooperate with anticancer therapy

The development of quantitative histology equipped with a digital imaging system as well as multiple IF stains visualized by confocal microscopy has enabled more precise quantification of TAMs and identification of subpopulations and their localization in intratumoral compartments [21, 26, 27]. The most popular biomarkers of TAM subpopulations belong to the scavenger receptor family and include CD206, CD163, stabilin-1, MARCO, CD36, and CD204 [9, 28]. They are expressed in CD68+ macrophages in tumor tissue [15, 29,30,31,32,33]. CD206 and CD163 are the most frequently used markers of M2-skewed TAMs and are correlated with metastasis and poor disease outcomes in many cancer types, including CRC [9, 34,35,36]. CD204-expressing TAMs are found in gastric, colorectal, breast, lung, ovarian, pancreatic and esophageal cancers; MARCO+ TAMs correlate with poor prognosis, especially in lung, hepatocellular, breast and pancreatic cancers; and high stabilin-1 expression is associated with poor patient survival in patients with pancreatic, gastric and bladder cancers [9, 37]. Among the potentially predictive TAM markers PD-L1, YKL-39, YKL-40, TIE2, TREM-1, CCL18, Siglec1, and SPP1 have also been proposed [9, 38,39,40,41] (Fig. 1). More detailed information about clinically significant TAM biomarkers and their key protumor molecular functions is summarized in our recent reviews [9, 28, 37, 42].

The foremost challenge in anticancer treatment is multidrug resistance, resulting in the development of metastasis during therapy or during the follow-up period [43]. Major TAM subtypes are correlated with metastasis in the majority of solid cancers [44,45,46]. A high number of CD68+ TAMs is correlated with hematogenous metastasis and lymph node metastasis in breast, lung, prostate, ovarian, prostate, esophageal, bladder, and renal cancers [47,48,49,50,51]. However, increased numbers of CD68+ TAMs can negatively correlate with hematogenous and lymphatic metastasis, with most documented examples in colorectal cancer [19, 52, 53]. Increased amounts of specific TAM subsets identified by CD163, CD206, stabilin-1, and TREM2 biomarkers correlate with both hematogenous and lymphatic metastasis in all cancer types studied [21, 34, 47, 50, 54,55,56,57,58]. Even in CRC, the presence of M2 macrophages, defined by CD206, CD163, and stabilin-1 expression, is indicative of metastasis [35, 36, 59]. Extended information can be found in recent reviews [9, 45, 46].

TAMs can acquire different functional phenotypes depending on their localization in intratumoral compartments, for example, in hypoxic or perivascular regions, within tertiary lymphoid structures, in the tumor nest or at the invasive front [9, 37]. The histological location of TAMs can affect patient prognosis. Pancancer transcriptomic analysis revealed that higher expression of the TIM4+ TAM signature located in the tumor nest was associated with significantly worse disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS), whereas higher expression of the TIM4+ TAM signature in tertiary lymphoid structures predicted significantly better DFS [60]. High heterogeneity of TAMs has been identified in distinct morphological compartments in human breast cancer [61,62,63]. TAMs in the human breast cancer parenchyma are negatively correlated with lymphatic metastasis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Hypoxic macrophages are well described in glioblastoma [64,65,66]. Hypoxic niches may reprogram TAMs to an immunosuppressive state, whereas hypoxia-induced TAMs can destabilize endothelial adherent junctions, impairing drug delivery [64, 65]. In the last several years, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics (ST) technologies have revolutionized the field of TAM identification [37, 67, 68].

ST combined with scRNA-seq enables the identification of transcriptomes of individual cells in the context of tissue architecture [69]. ST methods can be useful in identifying specific cell‒cell interactions formed by targeting TAM subpopulations, which can be valuable for the development of new immunotherapeutic drugs. FDA-approved immunotherapy aims to reactivate suppressed immune components via checkpoints [70]. However, limitations in the efficiency of this class of drugs are challenging in regard to clinical applications [71]. The limitations in the clinical efficacy of currently used immunotherapy may be due to the immunosuppressive mechanisms executed by TAMs [72, 73]. There is a large expectation that TAM-targeted therapies can increase efficiency and personalize prescriptions to increase the spectrum of targeted immunotherapy tools. Using spatial transcriptomics analysis, several key recent findings regarding essential TAM–TME interactions were identified. For example, potential mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) resistance were demonstrated in two independent studies on colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma via 10x Genomics Visium ST technology [74, 75]. In these tumors, a histological barrier formed by the interaction of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and SPP1+ macrophages decreases immunotherapy efficacy by limiting cytotoxic immune cell infiltration into malignant regions [74, 75]. In patients who respond to ICIs, SPP1+ macrophages/CAFs and immune cells interact easily [74, 75]. Another ST technology, NanoString GeoMx-DSP, was applied to examine the molecular mechanisms accompanying CRC development across normal mucosa, low-grade/high-grade dysplasia and cancer [76]. Dynamic changes are identified during the transition from normal tissue to dysplasia and from dysplasia to tumors [76]. There is increased infiltration of myeloid cells and a shift in macrophage populations from proinflammatory HLA-DR+ CD204- macrophages to HLA-DR-CD204+ immune-suppressive subsets [76]. Tumor samples from metastatic melanoma patients treated with ICIs were analyzed via GeoMx-DSP [77]. In the CD68+ compartment, PD-1 and HLA-DR expression in pretreated samples was significantly associated with resistance to therapy and poor survival, respectively [77]. We recently identified a new TAM-expressed marker for unfavorable prognosis in colon cancer—a regulator of glycolysis, PFKFB3 [14]. Using NanoString GeoMx, we found that in colon tumor tissue, PFKFB3 expression was linked to TAM accumulation and M2 polarization. PFKFB3 mRNA expression is negatively correlated with relapse and poor OS and PFS in colon cancer patients [14].

In our recent review, we thoroughly analyzed TAM phenotypic diversity in human cancers on the basis of the results of single-cell RNA-seq and ST technologies [37]. New functional biomarkers, including TREM2, MARCO, SPP1, C1QC, SIGLEC1, SIGLEC10, DC-SIGN, APOC1, CTSB, GPNMB, FOLR2 and others, annotated with immunosuppression, lipid metabolism, scavenging, antigen presentation, glycolysis, angiogenesis, hypoxia, and tumor cell invasion, have been defined for TAMs in different cancers [37]. Classical biomarkers of TAMs, including MRC1, CD163, MARCO, MAFB, and stabilin-1, comprise the gene signatures for novel TAM subsets. Several specific TAM subpopulations strongly correlate with disease outcome [37] (Fig. 1). According to recently collected data, TREM2, a surface lipid receptor, can be proposed as a new unprecedented macrophage biomarker with prominent immunosuppressive activity [78,79,80]. The number of TREM2+ TAMs is correlated with unfavorable survival or with a worse response rate to PD-1-based immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with colorectal cancer, lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, or melanoma [80,81,82,83,84,85]. The role of SPP1-expressing TAMs in tumor progression is under intensive investigation. Increased expression of SPP1 predicts poor prognosis in esophageal cancer, colorectal cancer, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, and glioma [41, 86,87,88,89,90]. GPNMB-expressing TAMs are specifically indicative of glioblastoma and are associated with poor prognosis in glioblastoma patients [91, 92].

Another state-of-the-art classification suggested for TAMs is based on multiomics data reflecting the molecular diversity of TAMs in mice and humans. The authors proposed a new consensus model of TAM subsets, including the following types of macrophages in cancer: interferon-primed TAMs (IFN-TAMs), immune regulatory TAMs (Reg-TAMs), inflammatory cytokine-enriched TAMs (Inflam-TAMs), lipid-associated TAMs (LA-TAMs), proangiogenic TAMs (Angio-TAMs), RTM-like TAMs (RTM-TAMs), and proliferating TAMs (Prolif-TAMs) [67]. In the most recent study, a comprehensive atlas of TAMs containing 23 clusters was identified by collecting scRNA-seq data from 17 human tumor types [93]. Some specific macrophage subsets are associated with the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [93]. The expression profiles of TAM subpopulations dissected by scRNA-seq revealed tumor-specific phenotypes that cannot be classified according to the M1/M2 dichotomy; despite being convenient and commonly used, the understanding of the functions and mechanisms of action of TAMs is limited. The current task for translational oncology is the molecular targeting of particular functions of TAMs and the delivery of drugs to detrimental and decision-making TAM subsets [94]. For example, the targeting of TREM2, SPP1 and MARCO is currently under extensive investigation, and the first in vivo studies demonstrated promising results associated with the inhibition of immunosuppression and further decreased tumor growth [86, 95, 96]. However, in the case of MARCO, the specificity of targeting MARCO+ TAMs but not alveolar macrophages is a critical issue. MARCO is expressed on macrophages in healthy human lungs and is responsible for the uptake of dust and other pollutant particles and bacteria from the environment [97]. If this silent cleaning function is blocked, a localized inflammatory reaction in the lungs may develop on pollutant particles and bacteria, or the pollutant may enter the bloodstream and lead to systemic inflammation up to sepsis, and autoantibodies to MARCO lead to severe inflammatory lung disease [98].

TREM2 deficiency or anti-TREM2 targeting in combination with anti-PD-1 therapy diminishes tumor growth, promotes tumor regression, and induces a proinflammatory program in macrophages in vivo [85, 99]. In lung cancer, TREM2+ monocyte-derived TAMs reduce NK cell activity by modulating interleukin (IL)-18/IL-18BP decoy interactions and IL-15 production [100]. A novel therapeutic option was also based on the combination of anti-TREM2 antibodies and an NK cell-activating agent, resulting in the inhibition of tumor growth in a lung cancer model [100]. Blockade of SPP1 with an RNA aptamer strongly inhibited tumor growth and tumor infiltration by CD206+ and F4/80+ macrophages in xenograft mouse models [86]. However, there is a striking example that TREM2+ giant TAMs are correlated with good prognosis in head and neck squamous carcinoma patients [101] (Fig. 1). Multinucleated giant macrophages (MGC) are associated with a favorable prognosis in treatment-naive and preoperative chemotherapy-treated patients, and MGC density increases in tumors following preoperative therapy. Functionally, MGC seems to have an active program of foreign body response to the extracellular cluster of keratin, and MGC also expresses CHIT1, a chitotriosidase (or chitinase) with highly conserved hydrolytic activity [102]. The foreign body reaction of giant cells is associated with improved OS in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) who receive preoperative chemoradiation therapy [103]. Despite the promising effects of TREM2 targeting in cancer, in obese cancer patients with metabolic disorders, TREM2+ TAM targeting can lead to adverse effects. TREM2 deficiency in this group of patients can lead to systemic hypercholesterolemia, body fat accumulation, and glucose intolerance [104]. It is related to the major function of TREM2, which is the regulation of tissue-level lipid homeostasis, suggesting that TREM2 is a key sensor of metabolic pathologies.

In the following chapters, the key tumor-supporting activities and molecular mechanisms of protumoral TAM programming are elucidated, and the results of most advanced clinical trials focused on TAM targeting are summarized and discussed.

Tumor-supporting functions of TAMs

TAM ontogeny and tumor initiation

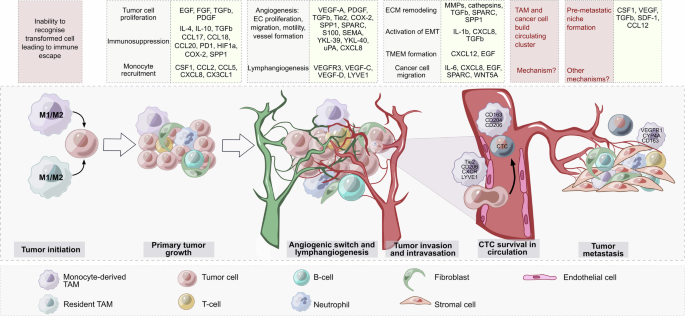

Local chronic inflammation, particularly low-grade inflammation, where macrophages constantly produce low levels of proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS), can drive tumor initiation by promoting genomic instability in malignant cells and, at the same time, by interfering with the ability of resident macrophages to distinguish between healthy somatic cells and transformed cells [105, 106] (Fig. 2). After transformed cells escape the first level of security control by resident macrophages, the proliferating cancer cell clones gain control over the resident macrophages located in close proximity to each other and start recruiting immune cells, including blood monocytes. Intensive heterogeneity in the site of chronic inflammation is due to the migration of diverse immune cells and somatic cells, and the activation of somatic cells does not allow macrophages to differ from malignant ones in terms of normal status. With the intensive growth of primary cancer cell clones, macrophages start to recognize tumors as healthy tissue and will now follow the instructions of cancer cells. In this coevolving cancer system, TAMs help tumors grow and escape other levels of immune control [11] (Fig. 2).

Functions and mediators of TAMs in tumor progression. Both resident macrophages and monocyte-derived macrophages can be involved in tumor initiation. Low-grade chronic inflammation drives genomic instability in cells. After the transformed cells escape immune control by macrophages, the growing cancer cell clones start recruiting blood monocytes. Other steps of tumor progression are controlled to a greater extent by monocyte-derived TAMs. TAMs secrete diverse protumor mediators (yellow boxes), which control many processes (gray boxes). TAMs are able to form an immunosuppressive microenvironment to facilitate angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis, activate molecular mechanisms accompanying tumor invasion and intravasation, support cancer cell survival in the bloodstream, and help to form a premetastatic niche. Many open questions remain regarding the precise mechanisms involved in the generation of circulating clusters consisting of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and TAMs as well as the role of TAMs in premetastatic niche formation

Some pathogenic microorganisms and viruses are able to initiate tumor growth. For example, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection of mucosal tissue may lead to head and neck, cervical, penile, anal and vaginal cancers [107]; hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection may induce hepatocellular carcinoma development [108]; Epstein‒Barr virus (EBV) drives nasopharyngeal carcinoma [109]; Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection is associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma [110].

The majority of viruses employ monocytes/macrophages as repositories and cells for productive replication [111]. The underlying mechanism of TAM involvement in virus-induced tumor growth has not been fully established, and TAM associations with clinical outcomes in patients with virus-associated cancers have still not been fully investigated. However, we performed several experimental studies indicating the crucial role of TAMs in virus-associated tumors. Increased infiltration by macrophages into the epithelium of the cervix was observed along with the progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia to invasive cancer [112]. Compared with lesions that regressed, low-grade intraepithelial lesions that persisted or progressed presented increased numbers of macrophages [112]. In an HPV16 E6- and E7-expressing TC-1 mouse tumor model, depletion of TAMs inhibited tumor growth and stimulated the infiltration of tumors by CD8+ lymphocytes, indicating that TAMs can suppress the antitumor immune response in HPV+ tumors [113]. Excessive M2-polarized macrophage accumulation was found in virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) compared with nonviral HCC [114]. The authors suggested that hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection induces M2-TAM polarization, leading to the development of liver fibrosis and, subsequently, to the development of HCC [114]. Kaposi’s sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV) infection of endothelial cells in vitro elevated Ang-2 expression to promote the migration and recruitment of monocytes into virus-induced tumors as well as IL-6, IL-10, and IL-13 expression to facilitate the differentiation and polarization of monocytes into TAMs [115]. KSHV-induced TAMs enhanced tumor growth and promoted tumor angiogenesis in a mouse model [115]. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection triggers chronic inflammation that can be associated with gastric cancer [116]. Tumor-derived exosomes from infected gastric cancer cells containing mesenchymal‒epithelial transition factors are internalized into macrophages and educate the macrophages toward a protumorigenic phenotype [116].

TAMs are highly plastic, and their activities can strongly depend on the signals produced by cancer cells, the intratumor localization of TAMs, and their interactions with the cellular and structural components of the TME [11]. All these parameters interact in the context of specific cancer types and can be affected by both local and systemic metabolic and hormonal factors [10, 105]. Finally, the application of anticancer treatment significantly impacts the functions of TAMs [94, 117,118,119]. In addition to cancer-specific secreted factors, the mechanisms responsible for molecular TAM heterogeneity are under intensive investigation [94]. In breast cancer, the adaptation of monocytes and macrophages to specific intertumoral locations within tumor regions can be a driver of TAM plasticity and heterogeneity [9, 120].

In addition to education by the TME, the ontogeny of macrophages also contributes to their heterogeneity [121]. The new paradigm of macrophage ontogeny confirmed that both embryonic tissue-resident macrophages originating from the yolk sac and fetal liver, as well as bone marrow monocyte-derived macrophages, constitute the TAM pool in tumor tissues [121,122,123]. Accumulated data demonstrate distinct transcriptional and functional programming of TAMs of different origins in breast, lung, ovarian, pancreatic, colorectal and brain cancers (reviewed by others) [121, 122]. In a mouse model of ovarian cancer carcinomatosis, CD163+Tim4+ omental macrophages were found to be of embryonic origin but not derived from bone marrow–dependent monocyte precursors [124]. The depletion of omental resident CD163+Tim4+ macrophages demonstrated that these cells play essential roles in tumor progression and the metastatic spread of disease in ovarian cancer [124]. In triple-negative breast cancer, tissue-resident macrophages are crucial cells that initiate tumor growth and facilitate recurrence and metastasis development [125]. In vivo, local depletion of mammary gland tissue-resident macrophages (MGTRMs) in mammary gland fat pads the day before cancer cell transplantation significantly reduces tumor growth and infiltration by TAMs, and depletion of MGTRMs at the site of tumor resection noticeably reduces recurrence and distant metastases and improves chemotherapy outcomes [125]. In contrast, FOLR2+ TAMs of resident origin in human breast cancer are associated with favorable prognosis [126]. FOLR2+ macrophages are located in the stroma in perivascular niches and interact with tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, which is positively correlated with CD8+ T-cell activation and patient survival [126]. The folate receptor beta (FOLR2) is a TAM biomarker that enables discrimination between TAMs that can originate from resident macrophages and TAMs that originate from newly infiltrating monocytes [126]. The ability of FOLR2+ macrophages (which are also found in healthy mammary glands) to activate cytotoxic T cells in breast tumors is highly important and allows us to hypothesize that, at least in breast cancer, it is easier for cancer cells to program incoming monocytes to differentiate into tumor-supporting TAMs to reprogram resident tissue macrophages, which still retain the ability to fight against cancer. Pronounced tumor-supporting activity of TAMs was also found in a murine model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), where protumoral IL-1beta+ TAMs were found to originate from monocytes but not from FOLR2+ resident macrophages [127]. Additionally, in human nonsmall lung cancer (NSCLC), the TAMs with the most pronounced tumor-supporting program have a monocyte origin [128]. However, tissue-resident macrophages support the formation of a protumorigenic niche in the early stages of NSCLC [129]. Another study discriminated between the distinct protumoral activities of TAMs of monocyte and resident macrophage origin, where monocyte-derived TAMs had increased antigen-presenting activity, whereas TAMs derived from resident macrophages of embryonic origin supported remodeling of the extracellular matrix [130]. Resident TAMs can have relatively stable programming that can be fixed at the epigenetic level; however, a certain level of reversibility is provided by the epigenetic enzymatic machinery. Using single-cell analysis of breast cancer tissue from patients and a PyMT breast cancer murine model, Ramos et al. identified novel biomarkers (and their combinations) to distinguish between pro- and antitumoral TAMs. CAMD1+ TAMs can be classified as protumoral on the basis of mouse studies, but their clinical correlations with the progression of human cancer remain to be identified [126]. However, a comparison of FOLR2+CAMD1- and FOLR2lowCAMD1+ TAMs clearly revealed that both subpopulations of TAMs express a specific mixture of the porotype “M1” and “M2” genes, highlighting the limitations of the frequently used M1 and M2 terminology [126]. Identifying the full spectrum of antitumoral effects of FOLR2+ TAMs and determining whether FOLR2+ can mark macrophages with similar or disease-specific programming at the epigenetic, transcriptional and metabolic levels in other cancers and in other pathologies are highly important, and FOLR2 has already been suggested as a target for antibody-based cancer immunotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia [131]. Thus, in human lung adenocarcinoma, single-cell transcriptome profiling suggested that FOLR2+ TAMs, as has been shown for breast cancer, also originate from tissue-resident (in this case, alveolar) macrophages. However, FOLR2+ TAMs are enriched in more malignant invasive lung adenocarcinomas and are likely involved in CD4+ T-cell recruitment [132]. In the kidney, FOLR2+ macrophages can interact with fibroblasts to promote fibrosis [133]. FOLR2+ macrophages appear very early in development, and FOLR2+ macrophages in the yolk sac have antimicrobial protective effects via the activation of neutrophils [134]. In mice with experimentally induced endometriosis, FOLR2+ macrophages exhibit proangiogenic and profibrotic activity [135], which, in the case of cancer, support tumor growth. The similarity or heterogeneity between FOLR2+ macrophages in various pathologies is an open question, which single-cell analysis allows us to address at the level of molecular profiling. However, the functionality of FOLR2+ macrophages is only emerging, and the role of folate receptor beta itself in macrophages in distinct pathophysiological settings needs clarification.

Another example of a recently identified biomarker exclusively expressed on distinct subpopulations of TAMs is CXCL9 and SSP1 in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [136]. The ratio of CXCL9/SSP1 TAMs, defined by the authors as CS TAM polarity, is positively associated with the infiltration of T cells, B cells and DCs in HNSCC patients [136]. As in the case of FOLR2+ TAMs and CAMD1+ TAMs, the transcriptomes of CXCL9+ TAMs and SSP1+ TAMs did not correspond to the traditional M1 and M2 dichotomy, and both CXCL9 and SSP1 expressed mixtures of genes traditionally categorized as M0-, M1- and M2-specific biomarkers. CS TAM polarity is also found in patients with lung and colorectal cancer; however, whether CS polarity is linked to TAM origination from resident macrophages remains to be clarified. It is of interest to determine whether FOLR2+ cells specifically fall into the CXCL9 and SSP1 categories.

TAMs of a resident origin can be more proinflammatory and profibrotic and can support epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Monocyte-derived TAMs are more immunosuppressive and can be responsible for antigen presentation, extracellular matrix degradation, and tumor spreading [121]. Programming of monocyte-derived TAMs in solid tumors can start systemically at least one differentiation step before macrophage maturation—at the level of circulating monocytes [13,14,15, 137,138,139,140]. Circulating monocytes, depending on the type of cancer, change their phenotype, transcription and metabolic programs [14, 15, 139]. Our most recent study applied targeted mass spectrometry and demonstrated cancer-specific changes in amino acid profiles in monocytes of patients with primary cancer before therapy onset [139]. The most pronounced differences in amino acid metabolism between monocytes from cancer patients and monocytes from healthy donors were found in breast cancer patients (decreases in tryptophan and aspartic acid) and in ovarian cancer patients (decreases in citrulline). Such changes can be indicative of the immunosuppressive programming of monocytes already in circulation; however, it is unclear whether these changes are induced by cancer-derived factors or whether these changes occurred earlier and predisposed individuals to cancer development. Large cohort studies are needed to identify which factors (genetic, environmental, and lifestyle) can affect amino acid metabolism in monocytes, and such knowledge can be applied to identify targets in monocytes that block their ability to differentiate into protumoral TAMs. Considering that TAMs in CRC can retain the ability to restrict tumor progression, a significant increase in aspartic acid and citrulline was identified in the monocytes of patients with CRC compared with those of patients with other types of cancer [139].

Thus, not only tumor microenvironmental factors but also TAM ontogeny and TAM localization may play a role in the prevalence of TAM functionality. In the TME, TAMs are able to support primary tumor growth, angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, tumor cell invasion, survival of cancer cells in circulation, metastatic niche formation, and resistance to therapy [141,142,143] (Fig. 2).

TAMs induce immunosuppression

In the TME, the major protumor function of TAMs is the production of diverse cytokines and growth factors that support the survival and proliferation of cancer cells, suppress their apoptosis, and increase their migratory potential needed for cancer cell invasion and extravasation into the circulation [144]. In established tumors, cancer cells reeducate TAMs to an immunosuppressive anti-inflammatory phenotype that supports tumor growth and facilitates tumor progression via the production of diverse tumor growth factors (e.g., EGF, FGF, TGFb, and PDGF), proangiogenic molecules (e.g., VEGF-A, SPP1, YKL-40, TIE2, and CXCL8), immunosuppressive factors (e.g., IL-10, PD-L1, CCL17, PGE, CCL20, and ROS), and matrix remodeling factors (e.g., matrix metalloproteinases [MMPs], uPAs, SPARC, and cathepsins) [17, 144, 145].

The second equally crucial activity of TAMs that is needed from the beginning of tumor development is the suppression of anticancer immune reactions (Fig. 2). TAMs can secrete large amounts of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10, which prevents the tumor cell-killing activity of CD8+ T cells, Th1 cells, and NK cells and activates Treg recruitment [142, 144, 145]. A number of immunosuppressive TAM subpopulations were revealed via single-cell analysis [37]. These TAM subsets include TREM2+ , MARCO+ , SPP1+ , CCL18+ , SIGLEC10+ , APOC1+ , IL10+ , and DC-SIGN+ macrophages, which are found in diverse types of cancer [37]. TAMs can suppress CD8+ cytotoxic T cells via the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, inhibition of T-cell proliferation, or activation of T-cell checkpoint blockade through the engagement of inhibitory receptors. TAMs also express ligands for the inhibitory receptors programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), which inhibit T-cell effector functions [145]. Immunosuppressive factors produced by TAMs in the TME include chemokines (e.g., CCL2, CCL5, CCL17, CCL18, CCL20 and CCL22), cytokines (e.g., HGF, PDGF-B, VEGF, IL-4, IL-10, and TGF-β) and enzymes (e.g., cathepsin K, COX-2, ARG1, and MMPs) [146]. In metastatic gastric cancer, the interaction of SPP1+ TAMs with CD8+ exhausted T cells via GDF15-TGFBR2 was demonstrated [147]. In the liver metastasis model, GDF15+ SPP1+ TAMs accumulated extensively in the metastatic site, but their amount was reduced after the blockade of GDF15 (a member of the TGFbeta superfamily). Inhibiting GDF15 significantly increased the infiltration of liver metastases by CD8+ T cells and reversed the immunosuppressive effect [147]. In a spontaneous BrafV600E-driven mouse melanoma model, specific depletion of CD163+ macrophages resulted in massive infiltration of activated T cells and significantly suppressed tumor growth [148]. After CD163+ TAM depletion, the remaining TAMs are re-educated toward the tumor-suppressing phenotype and express CD11c as well as the immune-modulatory molecules CIITA, CXCL9, and CD209D [148]. CD163+ exosomes derived from TAMs contribute significantly to immune suppression [149]. PD-1 is expressed by myeloid cells, including TAMs, in humans and mice [150]. TAM-derived exosomes activated by Rab27a carry high levels of PD-L1 and interact with stimulated, but not with unstimulated, CD8+ T cells, suppressing their proliferation and cytotoxic function in tumors. In a murine melanoma model, targeting macrophage RAB27A led to antitumor immune modulation and sensitized tumors to anti-PD-1 treatment [149]. The upregulation of Notch signaling in TAMs stimulates their immunosuppressive activity [151]. The combination of NOTCH1 signaling inhibition with anti-PD-1 therapy decreased tumor growth and activated the antitumor immune response in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer [151].

Myeloid-specific PD-1 targeting can play a decisive role in systemic antitumor responses [152]. In tumor-bearing mice, myeloid-specific rather than T-cell-specific PD-1 ablation more effectively decreased tumor growth and induced an increase in T-effector memory cells [152]. PD-1 expression on TAMs decreases phagocytic potency against tumor cells, whereas PD-1–PD-L1 blockade significantly increases phagocytosis by PD-1+ macrophages and reduces tumor growth in vivo [150]. Compared with T-cell-specific SHP-2 deletion, ablation of SHP-2, a regulator of PD-1 activity, in myeloid cells induced a decrease in tumor growth [153]. In tumor models of melanoma and fibrosarcoma, myeloid-specific SHP-2 ablation led to increased tumor infiltration by proinflammatory monocytes and concomitant recruitment and activation of CD4+ and CD8+ TEF cells. TAMs isolated from mice with myeloid-specific SHP-2 deletion presented increased expression of MHC II, CD86 and IFN-γ, indicating the activation of a proinflammatory phenotype with improved antigen presentation and costimulation capacity [153].

TAMs are essential for tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis

TAMs are key cells that control tumor angiogenesis [42, 154] (Fig. 2). Angiogenesis is a crucial process that supplies a growing tumor with nutrients and oxygen. The inhibition of angiogenesis has long been explored as a treatment strategy for colorectal, lung, renal, and cervical cancer and glioblastoma [155, 156]. Widely used FDA-approved antiangiogenic therapy is based on blocking the major proangiogenic factor VEGF or its receptor tyrosine kinases [156]. However, anti-VEGF therapy does not fulfill expectations [157]. The mechanism of therapy resistance in this case can be explained by the activation of alternative angiogenic pathways in response to VEGF blockade [158].

The first study demonstrating the role of TAMs in the angiogenic switch was performed in a mouse model of breast cancer [159]. After that, the ability of TAMs to secrete proangiogenic growth factors (first of all VEGF) and to facilitate the degradation of the perivascular extracellular matrix by a spectrum of released MMPs was shown by multiple studies (summarized in [42]). TAMs are a major source of different types of proangiogenic and extracellular matrix (ECM)-degrading mediators, including VEGF, EGF, PDGF, and TGF-β; angiopoietin 1 and 2 (Ang-1 and -2); matrix metalloproteinases (e.g., MMP2, MMP9, and MMP12); and serine or cysteine proteinases, such as cathepsins and plasminogen activator (PA), which have been identified in both murine models and patient samples [160, 161]. TAMs are also able to release molecules (e.g., TNFa, IL1a, and COX-2) that indirectly contribute to tumor angiogenesis via the induction of a proangiogenic program in tumor cells [160].

Many “nonclassical” growth factors, enzymes, ECM proteins, and other mediators produced by TAMs are involved in the regulation of angiogenesis [42]. These proteins include members of the S100 family, the SEMA family, COX-2, SPP1 (osteopontin), SPARC (osteonectin), Tie-2, and chitinase-like proteins (YKL-39, YKL-40), among others. For example, members of the S100A class (e.g., S100A4, S100A7, S100A8, S100A9, and S100A10) secreted by TAMs induce endothelial cell (EC) proliferation, migration and angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo [162,163,164,165,166].

TAMs are a main source of the chitinase-like protein YKL-39 in breast cancer tissue [167]. YKL-39 combines two activities: it facilitates monocyte recruitment and promotes angiogenesis in vitro [39]. Elevated YKL-39 expression in tumors after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is predictive of an increased risk of distant metastasis and a poor response to NAC in patients with breast cancer [39].

Osteopontin (OPN, encoded by SPP1) promotes EC junctional destabilization, actin polymerization and EC motility in vitro and increases microvascular density in vivo [168]. Single-cell RNAseq analysis of colorectal cancer samples revealed that the SPP1-positive population of TAMs was strongly enriched in the tumor angiogenesis, ECM receptor interaction, and tumor vascularisation pathways [89, 169, 170].

TAMs can also express antiangiogenic regulators. For example, SPARC inhibits EC migration and vessel formation in vitro, decreases vessel number, and promotes disruption of the vascular basement membrane in vivo [171]. In our recent study, we demonstrated the clinical value of several angiogenesis regulators produced by TAMs [41]. We analyzed the gene and protein expression levels of S100A4, SPARC and SPP1 in CRC tissue and evaluated their correlations with disease outcome and progression parameters. High S100A4, SPARC and SPP1 mRNA levels were found to be independent prognostic factors for poor survival in CRC patients. Analysis of human CRC tissues revealed that S100A4, SPP1 and SPARC are expressed by stromal compartments, particularly TAMs, and are strongly correlated with macrophage infiltration [41].

The subset of perivascular TAMs (PvTAMs) was thoroughly described by Lewis C. and colleagues in a comprehensive review [172]. In primary tumors, perivascular TAMs mainly express TIE2 and VEGFA and activate leukocyte recruitment and regulation, facilitate the intravasation of tumor cells, promote angiogenesis, and support tumor relapse after chemotherapy. In the metastatic site, the PV macrophage subset, which expresses CCR2 and VEGFA (but not TIE2), promotes cancer cell seeding through direct interactions with cancer cells at the vessel wall and subsequently promotes colonization [172]. Tie2 receptor-expressing TAMs facilitate tube formation and promote EC quiescence and vascular maturation in vitro [173]. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) induces the accumulation of TAMs around blood vessels and increases the expression of markers of a protumor phenotype, including folate receptor-beta (FR-β), MRC1 (CD206), CD169 and VISTA, in PvTAMs in human and mouse prostate cancers [174]. In human prostate tumor samples taken before ADT, the density of perivascular FR-β+ CD68+ TAMs was significantly greater in patients who did not respond to ADT than in responders; there was also a nonsignificant trend for PV FR-β+ CD68+ TAMs to also be greater after ADT in nonresponders than in responders [174]. In human invasive breast cancer and MMTV-PyMT tumors, PvTAMs expressing LYVE1 are arranged in close proximity to aSMA+ pericyte-like mesenchymal cells, forming a proangiogenic niche near the vasculature followed by tumor progression [175]. The formation of this niche is dependent on PDGFRα:PDGF-CC cross-talk [175]. LYVE1+ PvTAMs form multicellular nests proximal to blood vessels that are dependent on IL-6-driven CCR5 expression by these TAMs. HO-1 expression on LYVE1+ PvTAMs induces immune exclusion of CD8+ T cells from the TME [176]. PvTAMs can be a transitory subset of CCR2-dependent recruited TAMs that migrate proximally to vessels after 10–14 days of recruitment [177]. The first recruited motile streaming TAMs differentiate into CXCR4-expressing macrophages in a TGF-β-dependent manner and cooperate with CXCL12-expressing cancer-associated fibroblasts in the perivascular niche to promote cancer cell intravasation [177]. Intratumor TAMs located in the tumor parenchyma adopt an mTORC1-low state dependent on tuberous sclerosis complex 1 (TSC1), a negative regulator of mTORC1 signaling [178]. TSC1 deficiency in TAMs reprogrammed them to a pro resolve phenotype with increased mitochondrial respiration, which promoted TAM accumulation in the high-oxygen perivascular region. Perivascular TSC1-deficient TAMs outcompeted PROCR-expressing endothelial cells and suppressed neoangiogenesis, causing tumor tissue hypoxia and starvation-induced cancer cell death [178].

Several factors produced by TAMs are also responsible for the induction of lymphangiogenesis [160]. Among them, VEGFR-3 and its ligands, VEGF-C and VEGF-D, play key roles in lymphangiogenesis [160]. A recent study demonstrated that VEGF-C-expressing TAMs reduce the hematogenous dissemination of mammary cancer cells to the lungs while concurrently increasing lymph node metastasis in a murine breast cancer model [179]. VEGF-C-expressing TAMs express podoplanin and normalize tumor blood vessels [179].

Thus, TAMs control many steps of the angiogenic switch, and to improve the efficacy of currently available antiangiogenic therapies, simultaneous targeting of TAMs is needed [160]. For example, bevacizumab (an anti-VEGF therapy) combined with the CCL2 inhibitor mNOX-E36 decreased the recruitment of TAMs and angiogenesis, resulting in decreased tumor volume in a rat glioblastoma multiforme model [180]. Combined treatment with sorafenib, a small-molecule kinase inhibitor, and TAM depletion with zoledronic acid promoted the inhibition of primary tumor growth and lung metastasis in an orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma model [181].

TAMs facilitate tumor cell invasion

The interaction between tumor cells and TAMs contributes to invasion and metastasis, which are the main reasons for the poor prognosis of patients [182]. The metastatic spread of cancer cells starts with their invasion into the bloodstream [182, 183]. To invade, several steps must be completed by cancer cells, including loss of attachment to the surrounding tissue structures, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, ECM degradation, and increased cell motility [143, 184, 185]. TAMs are able to regulate all steps of the metastatic cascade [46]. Secreted by TAMs, IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-α, and TGF-β promote EMT in cancer cells [186, 187]. To initiate ECM degradation, TAMs secrete several proteolytic enzymes, including cathepsins, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs, such as MMP7, MMP2, and MMP9), and serine proteases [46, 143, 188].

In addition to the functions of TAMs, the contents of cytokines, enzymes, and growth factors and the composition of the ECM in the TME can be defined. The scavenging function of TAMs can control the concentration of growth factors and ECM regulatory components via active scavenger receptor-mediated internalization and degradation [28]. Scavenger receptors (SRs) are a large superfamily of transmembrane proteins with high structural diversity. In the TME, they can recognize and internalize a great variety of ligands, including cytokines, growth factors, modified lipoproteins, and apoptotic cells [28, 189]. The most popular biomarkers of TAMs are scavenger/endocytic receptors [28]. Among them, many international cohorts of cancer patients have shown negative prognostic value for TAMs expressing CD68, CD163, CD204, CD206, MARCO, and stabilin-1 [9, 28]. In several in vitro and in vivo studies, both the pro- and antitumor activities of SRs have been demonstrated to be dependent on the cancer type and type of tumor model [28]. Tumor-supporting activity is related to facilitating tumor invasion, proliferation and migration (mediated by CD204, CD206, CXCL16, stabilin-1, and RAGE), M2-like TAM polarization (by CD36, LOX-1, CXCL16, CD163, and RAGE), and tumor angiogenesis (by CD68, Dectin-1, and RAGE). Tumor-suppressing activity includes the inhibition of tumor angiogenesis (by CD204), tumor invasion (by RAGE), the clearance of tumor cells (by MARCO) and the promotion of M1-like TAM polarization (by CD204 and RAGE) [28]. However, little is known about tumor-related ligands for the SR expressed by TAMs. We identified two tumor-specific ligands of Stabilin-1, SPARC and EGF [33]. In a murine breast cancer model, stabilin-1 was able to promote tumor growth, and this function was linked to the stabilin-1-mediated scavenging of SPARC [33]. The extracellular domains of stabilin-1 can interact not only with SPARC but also with two human chitinase-like proteins, SI-CLP and YKL-39, and this interaction can contribute not only to clearance but also to the intracellular sorting of newly synthesized YKL-39 and SI-CLP and their ability to be secreted [39, 102, 190]. Most recently, we reported that stabilin-1 mediates the clearance of the most potent growth factor that supports the proliferation of cancer cells, EGF [191]. Thus, the cumulative effect of stabilin-1+ TAMs must be considered in a cancer-specific context, and taking stabilin-1 as an example, we suggest that blocking SR function to reprogram TAMs is far from simple and unambiguous, reflected by the absence of advanced clinical trials in this direction (for details, see the last chapter of this review). MARCO is another SR that can carry out some antitumor functions via phagocytosis of tumor cells [192]. However, transcriptomic analysis clearly demonstrated that MARCO is expressed by immunosuppressive TAMs [31, 37]. MARCO targeting has been successful in animal models, where anti-MARCO antibodies block tumor growth and metastasis [95]. However, as we mentioned previously, anti-MARCO antibodies can lead to unfavorable systemic inflammatory complications in patients.

Compared with keratinocyte-derived or melanoma-derived melanosomes, macrophages cografted with fibroblast-derived melanosomes induced enhanced tumor growth and proliferation as well as vascularization in vivo [193]. In vitro, melanoma cells incubated with conditioned media from macrophages loaded with fibroblast-derived melanosomes presented increased proliferation rates and invasive potential. In vitro angiogenesis is induced via the following mechanism: the delivery of AKT1 into macrophages from fibroblast-derived melanosomes activates mTOR phosphorylation, resulting in excessive VEGF secretion [193]. HO-1-expressing TAMs are indicative of tumor invasion and are found at the invasive tumor margin in both human melanoma tumors and a mouse melanoma model in vivo [194]. Myeloid-specific HO-1 deletion in a melanoma model in vivo reduced lung metastasis but did not affect primary tumor growth, indicating that HO-1-expressing TAMs promote metastasis [194].

The next step of the metastatic cascade after matrix remodeling and EMT activation is the invasion of tumor cells into blood vessels [182, 183]. This process is mediated via a paracrine loop involving tumor-synthesized CSF1 and macrophage-produced EGF that drives the migration of tumor cells toward blood vessels [144] (Fig. 2). The direct contact of mammalian‐enabled (MENA)hi tumor cells with perivascular TAMs and endothelial cells at the intravasation site is known as the tumor microenvironment of metastasis (TMEM) [144, 195]. TMEM has been described most thoroughly in breast cancer and represents an independent prognostic indicator of metastatic risk in breast cancer patients [196,197,198]. The crucial role of the TMEM is VEGFA-dependent disruption of endothelial cell-to-cell adhesions, transient vascular leakiness and tumor cell intravasation [177]. Perivascular TAMs in the TMEM pathway express high levels of the tyrosine kinase receptor TIE2 (also known as CD202b) and CD206 [195]. Perivascular TAMs expressing Tie2 (TEMs) can promote tumor angiogenesis by regulating vascular maintenance (cell proliferation, migration, and stabilization) [42]. TEMs express high levels of other proangiogenic factors, such as MMP-9 and VEGF, and M2-polarize (due to increased levels of COX-2, CD206, and WNT5A) [42, 195]. Hughes R. and others demonstrated that MRC1+TIE2HiCXCR4Hi TAMs accumulate around blood vessels in both LLC1 tumors and orthotopic 4T1 and MMTV-PyMT implants after chemotherapeutic impact, as well as in human breast carcinomas after neoadjuvant treatment with paclitaxel [199]. The accumulation of MRC1+TIE2HiCXCR4Hi TAMs was accompanied by increased CXCL12 expression in vascularized, well-oxygenated areas after chemotherapy, which was important for tumor revascularization and relapse after chemotherapy. CXCR4 inhibition results in impaired tumor revascularization and regrowth after chemotherapy [199]. Monocytes are recruited to tumor sites via CCR2 signaling, where tumor cell-secreted TGF-β induces CXCR4, stimulating them to migrate toward CXCL12-expressing perivascular cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). In this state, CXCR4-expressing perivascular TAMs can promote cancer cell intravasation [177]. LYVE-1-expressing TAMs have also been characterized recently as perivascular macrophages that create a proangiogenic niche [175, 176].

Once a cancer cell has intravasated into the bloodstream, it becomes a circulating tumor cell (CTC) and can initiate metastasis or be cleared from the blood circulation [200] (Fig. 2). In the bloodstream, CTCs can form clusters with other tumor or nontumor cells, leading to the formation of tumor hybrid cells (THCs). THCs formed by the fusion of CTCs with macrophages exhibit novel properties, including increased proliferation and migration, drug resistance, a decreased apoptosis rate, and the avoidance of immune surveillance [200,201,202]. In vitro coculture of CTC lines obtained from lung cancer patients with peripheral blood mononuclear cells resulted in the induction of monocyte differentiation into TAMs, which secreted OPN (SPP1), MMP9, chitinase-3-like-1 (YKL-40), and the platelet factor responsible for leukocyte recruitment, migration, and invasion [203]. These macrophage–tumor cell hybrids express M2-like macrophage markers (CD163, CD204, and CD206) and epithelial markers (cytokeratins and EpCAM) and are found in the peripheral blood of patients with PDAC, melanoma, and breast, ovarian, and colorectal cancer [200, 204]. It was also demonstrated that macrophage–tumor cell hybrids are able to promote the formation of metastatic lesions when transplanted into mice, suggesting their role in preparing “niches” for colonization by metastasis-initiating cells [204]. The targeting of TAMs in the context of circulating micrometastasis is highly attractive, primarily because of the low degree of invasiveness of these cells for drug delivery; however, this idea has rarely been explored experimentally.

TAMs are critical for premetastatic niche formation

TAMs have been suggested to contribute to the formation of premetastatic niches [45, 46, 205,206,207] (Fig. 2). TAMs themselves are recruited to premetastatic niches by a variety of tumor-secreted factors, such as CCL2, CSF-1, VEGF, PDGF, TNF-α, and TGF-β, where they act in a similar manner as in primary tumors, promoting cancer cell survival [205, 208]. Tumor-derived exosomes that program myeloid cells to be protumoral and proangiogenic can also be important for metastatic niche formation [144, 209]. Exosomes derived from colorectal cancer cells and pancreatic cancer cells that are engulfed by Kupffer cells direct them to initiate favorable premetastatic niche formation in the liver [210, 211]. Metastatic niches are seeded by VEGFR1+ myeloid cells [206]. In spontaneous metastasis models of 4T1 breast cancer and B16F10 melanoma, cytochrome P450 (CYP) 4 A (CYP4A)+ TAMs drive premetastatic niche formation and metastasis development [206]. The pharmacological inhibition of CYP4A reduces lung premetastatic niche formation and the metastatic burden in vivo [206]. In a mouse model of ovarian cancer, CD163+Tim4+ resident macrophages residing in the omentum were shown to be responsible for the metastatic spread of cancer cells [124]. Genetic and pharmacological depletion of CD163+Tim4+ omental macrophages prevents tumor progression and the metastatic spread of disease [124]. The CCL2‒CCR2 axis in the breast tumor microenvironment is crucial for metastasis in the lungs and bones [212, 213]. In lung metastasis of breast cancer, the functional interaction of endothelial cells with perivascular macrophages induces vascular niche formation [214]. Mechanistically, perivascular tenascin C expressed by mammary tumor cells triggered TLR4-dependent activation of perivascular macrophages in the premetastatic niche, which induced the upregulation of INHBB, LAMA1, SCGB3A1 and OPG expression in endothelial cells, which are responsible for metastatic colonization in the lung in vivo. This effect was not suppressed by anti-VEGF therapy; however, combined inhibition of TLR4 and VEGF resulted in more efficient suppression of metastasis than single treatments in vivo [214]. The CXCL10-CXCR3/TLR4 axis is essential for the induction of CCL12 expression in alveolar macrophages in the lung and the formation of the premetastatic niche [215]. Tumor cell-derived CXCL10 increases CCL12 in alveolar macrophages, which leads to the recruitment of monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in premetastatic lungs and the formation of metastases [215]. The formation of a premetastatic niche in the lungs can be dependent on platelet clot formation by tumor cells [216]. Tissue factors derived from tumor cells induce coagulation on tumor cells and then macrophage recruitment. The ability of the clot to recruit CD11b+ macrophages is critical for metastatic cell survival and premetastatic niche establishment in mice [216].

The precise molecular mechanisms of TAM-mediated premetastatic niche formation are still unclear. The role of TAMs in premetastatic niche formation in organs other than the lung needs further investigation.

In summary, this experimental evidence highlights the crucial role of TAMs in all steps of tumor development, beginning with tumor growth support and immune evasion and ending with metastasis formation at distant sites (Fig. 2).

Molecular pathways that program TAMs and new options for reprogramming

Mechanistically, the protumoral functions of TAMs are programmed at the interface of epigenetic, transcriptional and metabolic events [10]. Macrophages in their advanced polarization state are mostly nondividing cells, and whether the limited proliferation of macrophages significantly contributes to their quantity and differentiation in pathology is still under debate.

Considering that macrophages, in contrast to B cells and T cells, do not undergo genetic rearrangements during their differentiation, the whole spectrum of macrophage subpopulations, as well as their capabilities and limitations in plasticity, are controlled by epigenetic events [217,218,219,220,221]. All levels of epigenetic control, DNA methylation, histone coding, miRNA and long noncoding RNA can contribute to the TAM functional phenotype; however, the speed of response to microenvironment stimuli, as well as reversibility, is much greater at the histone coding and miRNA levels, whereas the stability of programming is the highest at the DNA methylation level.

DNA methylation in the programming of TAMs

DNA methylation is crucial for monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation [222]. The best-known function of DNA methylation is preventing the transcriptional machinery from assembling on a hypermethylated promoter, resulting in the silencing of gene transcription [223]. Hypermethylation is frequently but not necessarily associated with cell division and is reversible. In cancer cells, DNA methylation is critical for the suppression of the expression of tumor suppressor genes, whereas loss of DNA methylation leads to the overexpression of oncogenes [224]. The effect of tumors on the DNA methylation landscape of TAMs was recently examined in a 4T1 mouse model of triple-negative breast cancer [225]. Compared with those in tumor-bearing mice, the DNA methylation landscapes in macrophages and monocytes from healthy control mice were distinct. Cancer cells significantly change the DNA methylation landscape of macrophages and, to some extent, bone marrow-derived monocytes (BMDMs). The authors were able to link microenvironmental signals to the cancer-specific DNA methylation landscape of TAMs by considering published single-cell transcriptome data, and the integrated approach linked altered cytokine production in the TME and the induction of specific transcription factors linked to the epigenetic reprogramming of TAMs [225]. This study provides a new perspective for the validation of these findings in patient cohorts.

In patients, DNA methylation was suggested to control the expression of interleukin-4-induced-1 (IL4I1, L-phenylalanine oxidase) in M2-like TAMs in human glioma [226]. IL4I1 is associated more frequently than IDO1 or TDO2 with the activity of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), a ligand-activated transcription factor that can sense tryptophan (Trp) catabolites, enhancing tumor malignancy and suppressing antitumor immunity [227,228,229]. IL4I1 activated AHR through the generation of indole metabolites and kynurenic acid [228]. Ectopically expressed IL4I1 increased the motility of AHR-proficient but not AHR-deficient cells, and CM from IL4I1-expressing cells reduced T-cell proliferation. The expression levels of IL4I1 are correlated with reduced survival in glioma patients, and high IL4I1-expressing tumors are characterized by an enrichment of suppressive immune cells (MDSCs) and Tregs; however, the major cell types expressing IL4I1 in glioma were not identified in this study [228]. An integrated bioinformatics approach revealed that IL4I1-expressing macrophages in cancer are immunosuppressed by tryptophan degradation, facilitating the recruitment of regulatory T cells into tumors [230]. More recently, reduced methylation of the promoter of IL4I1 was demonstrated to be correlated with aggressive progression and a dismal prognosis for patients with glioma. However, the mechanism that removes methylation from the IL4I1 promoter in TAMs in glioma is unknown [226].

Histone code in TAM programming

The variability of the enzymatic machinery for both the methylation and demethylation of DNA is significantly limited compared with the broad spectrum of enzymatic machinery that catalyzes a broad spectrum of posttranslational histone tail modifications, making the histone code principal for TAM reactions to the constantly changing tumor microenvironment. Histone modifications, also known as a histone code, are crucial for the high flexibility of macrophages in adjusting their transcriptional mechanisms to the complex and dynamic microenvironment and can be fully explored by cancer cells to program TAMs to support tumor development [10]. The histone code covers a number of posttranslational modifications, such as methylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, citrullination, sumoylation and others, that can modify hotspot amino acids in histone tails [231]. Such modifications can be single, double or triple on the same amino acid and can be homotypic or heterotypic. The sum of the modifications of one amino acid is referred to as a histone mark, and histone marks can be activated, facilitating the relaxation of chromatin, or repressed, stimulating chromatin condensation. The histone code defines a unique functional state of chromatin that regulates various chromatin-templated processes [232]. The sum of histone marks on the promoter defines the level of its availability for the transcriptional machinery and its unique functional state within chromatin. Histone-modifying enzymes can regulate macrophage phenotypes through the addition or removal of functional groups, such as acetyl/methyl groups. Histone modifications are reversible; for example, acetylation and deacetylation are catalyzed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), whereas histone methylation is catalyzed by histone methyltransferases and demethylases, respectively. The variability and reversibility of the histone code and the regulation of the histone-modifying enzymatic machinery ab by stimuli from the microenvironment offer and enable high plasticity for macrophages, including TAMs. Histone acetylation always results in the generation of activating histone marks, while the methylation of histones, depending on the amino acid position and number of methyl groups added, can both be activated and repressed [231]. The histone code acts not only on promoters but also on enhancers that are critical for the differentiation of myeloid precursors, starting from bone marrow progenitors, and for the maturation of macrophages [233, 234]. The best-known activating histone modifications that act on the promoters of genes that control inflammatory programs in macrophages under infectious or metabolic conditions include H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K27ac [235,236,237,238]. M2-macrophage marker genes are epigenetically regulated by reciprocal changes in histone H3K4 and H3K27 methylation, and H3K27 is removed by the H3K27 demethylase Jumonji domain containing 3 (Jmjd3). IL-4-dependent Jmjd3 expression was mediated by the interaction of STAT6 with the Jmjd3 promoter. Increased Jmjd3 expression contributes to a decrease in H3K27me2/3 marks as well as the transcriptional activation of M2 marker genes [239]. A recent study applied H3K27ac-ChIP-seq in M2 macrophages and THP-1 cells and revealed that M2-specific enhancers were enriched in Yin Yang, 2 zinc finger nuclear transcription factor (YY1) signals, while YY1 increased macrophage-induced prostate cancer progression by upregulating IL-6 [240]. Histone-modifying enzymes (HMTs, HDMs, HDACs) control the M2 direction of macrophage polarization, which is typical for TAMs, and are of interest for the design of anticancer drugs; however, the typical problem of specific delivery has to be solved to avoid target effects [10]. HDAC2 was shown to regulate the M2-like TAM phenotype via acetylation of histone H3 and the transcription factor SP1 [241]. Suppression of HDAC2 in TAMs suppressed their protumoral secretome, while the spatial proximity of HDAC2-overexpressing M2-like TAMs to cancer cells was significantly correlated with poor overall survival in lung cancer patients [241].

The assembly of the transcriptional machinery on promoters marked by acetylated histones is mediated by bromodomain-containing proteins (BRDs) and some extraterminal motif-containing proteins (BETs) that possess the ability to identify acetylated lysine residues present in histones and other proteins [242]. BRDs and BETs can inhibit or activate the assembly of the transcriptional machinery regulating the production of inflammatory cytokines with crucial functions in tumor progression (IL-1b, IL-6, TNFa, and MCP-1) [10, 243,244,245,246].

SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complexes, where BRDs (for example, BRD7 and BRD9) are involved, can regulate inflammatory gene expression in macrophages through interactions with lineage-determining and stimulus-regulated transcription factors [247]. Deletion of SWI/SNF subunits in mice resulted in developmental defects in hematopoietic lineages [248, 249]. However, the exact events that can be controlled by BRD and BETs in TAMs remain to be identified. Interestingly, one process that can be affected by BETs is the inhibition of TAMs [250]. NHWD-870, a BRD4 inhibitor that has been reported to be more potent than three major clinical-stage BET inhibitors, BMS-986158, OTX-015, and GSK-525762, blocks the proliferation of TAMs in subcutaneously implanted H526 and A2780 tumors, at least partially by reducing the expression and secretion of CSF1 by cancer cells [250]. Whether NHWD-870 changes the epigenetic landscape in TAMs is the next open question.

Lactylation of histones as a link between tumor metabolism and TAM programming

Recently, the lactylation of histones in TAMs has attracted the attention of leading research groups working on the epigenetics of TAMs. Lactate is a byproduct of glycolysis and is produced in high amounts by rapidly proliferating cancer cells via aerobic glycolysis. Moreover, the level of lactate can also be elevated under hypoxic conditions, which are typical for rapidly growing tumors. A groundbreaking study by Colegio et al. in 2014 revealed that lactate can induce prohumoral, M2-like programming of tumor-associated macrophages [251]. M2 polarization is mediated by HIF1a but, at least partially, is independent of the IL4-induced pathway [251]. In this study, VEGF and Arg1 were used as read-outs for protumoral M2 polarization of TAMs; however, the downstream events leading to the activation of the promoters of VEGF and Arg1 were not addressed, and only a limited number of flow cytometry-identified parameters of M2 polarization were analyzed.

Transient glycolytic activation of peritumoral monocytes in hepatocellular carcinoma was found to induce sustained expression of carbonic anhydrase XII (CA12) on tumor-infiltrating macrophages via autocrine cytokines and the HIF1α pathway [252]. CA12 mediates the survival of macrophages in acidic tumor microenvironments and stimulates TAMs to produce large amounts of CCL8, which enhances EMT in cancer cells. The accumulation of CA12+ macrophages in the tumor tissues of patients with HCC is associated with increased tumor metastasis and reduced survival in patients with HCC [252]. The fact that transient glycolytic activation in monocytes has a prolonged effect on TAMs can be explained by epigenetic metabolic memory. One mechanism of such memory was identified in human primary monocyte-derived macrophages, where exposure to hyperglycemia resulted in the increased presence of activating histone marks on the promoters of the S100A9 and S100A12 genes [238]. Another potential mechanism of metabolic memory in TAMs is the lactylation of histones.

Histone lactylation was found to be an epigenetic “lactate timer” that switches the acute inflammatory status to the healing program in macrophages [253]. The action of the “lactate timer” can explain why, even in hot tumors, where inflammation can be expected to instruct TAMs toward antitumor activity, there is a failure to reach the level of acute inflammation, corresponding to the levels of the acute antibacterial responses of macrophages. In ovarian cancer, lactate is elevated in the serum of cancer patients and supports tumor growth via the activation of CCL18 expression via H3K18 lactylation in macrophages to promote tumorigenesis [254]. In cancer cells, lactylation of H3K18 can activate nuclear pore membrane protein 121 (POM121), which facilitates the nuclear translocation of MYC, its binding to the CD274 promoter, and the induction of PD-LI expression [255]. Inhibition of glycolysis cooperated with anti-PD-L1 therapy by inducing CD8+ T-cell antitumor effects in mouse NSCLC xenograft models, and elevated levels of overall lysine lactylation (Kla) and specific lactylation of H3K18 (H3K18la) correlated with unfavorable prognosis in NSCLC patients [255]. However, this study did not consider potentially elevated histone lactylation and elevated expression of POM121 in TAMs, and correlation analysis of the elevated levels of Kla and H3K18la performed by single IHC staining did not allow the identification of cell-specific histone modifications. H3K18la was also elevated in epithelial ovarian cancer patient tissues and correlated with poorer OS and PFS; however, the contribution of H3K18la in TAMs remains to be examined [256]. Additionally, the role of H3K18la-mediated elevation of POM121 expression specifically in TAMs cannot be excluded; however, information about the role of POM121 in macrophage activation is extremely limited, but at least one study reported anti-inflammatory effects of POM121 in POM121fl/fl Lyzm-Cre+ mice, which presented elevated levels of lung inflammation after LPS-induced acute lung injury, with increased TNF-α and IL-6 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) [257]. The anti-inflammatory effect of POM121 was explained by the inhibition of the NFkappaB pathway in macrophages.

Compared with acetylation, the lactylation of lysines in histones 3 and 4 (H3 and H4) is delayed and is not found on the promoters of acute inflammatory genes but rather on the promoters of genes related to the wound healing activity of macrophages [253]. The wound healing activity of macrophages involves their support of somatic cell migration and proliferation, tissue vascularization, ECM remodeling and suppression of antigen-specific adaptive immunity. These primarily healthy functions of macrophages, which are needed to close wounds, are activated in the tumor microenvironment and are explored by cancer cells to proliferate and enter the vascular system to metastasize. The identification of lactate as a mediator that can change epigenetic programs in macrophages explains why this healing program can never be completed, since lactate is constantly produced by cancer cells. Currently, the candidate lactate writers are p300 (well-known histone acetyltransferase), KAT8 and AARS1 [253, 258]. The overexpression or deletion of p300 in cancer cell lines results in increased or decreased Kla levels, as shown by immunoblotting; however, the effects are not very strong and have not been quantified [253]. Supporting data were produced in murine macrophage-like RAW264.7 cells, where the inhibition of P300 by C646 resulted in a decrease in total protein lactylation levels and increased expression of the inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α [259].

Affinity chromatography, mass spectrometry and in vitro studies in HGC27 cancer cells via loss-of-function and gain-of-function approaches identified alanyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (AARS1), a bona fide lactyl-transferase, which directly uses lactate and ATP to catalyze protein lactylation [258]. AARS1 was found to sense intracellular lactate and translocate it into the nucleus to lactylate and activate the YAP-TEAD complex in HGC27 cells. The authors hypothesized that AARS1, as a Hippo target gene, can form a positive feedback loop with YAP-TEAD, promoting gastric cancer cell proliferation, whereas AARS1 expression is correlated with poor prognosis in GC patients [258]. However, whether AARS1 can act in TAMs has not been investigated. The lysine acetyltransferase KAT8 is a pan-Kla writer on many protein substrates. The interest in KAT8 was due to its interaction with elongation factor 1 alpha (eEF1A2), which was identified via immunoaffinity purification and subsequent LC–MS/MS in eEF1A2-overexpressing HCT116 cells [260]. KAT8 expression was negatively correlated with overall survival (OS) in CRC patients, whereas KAT8 expression was positively correlated with the global Kla level in CRC tissues. Lactylation of eEF1A2K408 supported tumorigenesis via increased protein synthesis, whereas deletion of KAT8 inhibited the growth of colorectal cancer in nude mice injected with HCT116 cells with or without KAT8 depletion. The authors suggested KAT8 as a potential therapeutic target for CRC [260]. However, similar to AARS1, the role of KAT8 in TAMs, which are highly heterogeneous in CRC and can support or inhibit tumor growth, has not been addressed.

The direct cancer-supporting effect of histone lactylation in TAMs was demonstrated in a prostate cancer model of prostate-specific PTEN/p53-deficient genetically engineered mice [261]. Decreased lactate production in PI3Ki-treated cancer cells suppressed histone lactylation (H3K18lac) within TAMs. This promoted TAM phagocytic activity, which was further enhanced by androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) combined with aPD-1 treatment. The cancer-promoting function of histone lactylation in TAMs has been shown in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) patients, whereas single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis of biopsy samples demonstrated a direct correlation between high glycolytic activity and TAM phagocytosis suppression [261]. The same group tested whether the addition of trametinib (MEK inhibitor) to the inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) copanlisib can enhance tumor control in prostate-specific PTEN/p53-deficient genetically engineered mice [262]. They reported an 80% overall response rate via additive suppression of lactate within the TME and histone lactylation at H3K18lac in TAMs relative to monotherapy with copanlisib (37.5%). In resistant mice, Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation via a feedback mechanism results in the restoration of lactate secretion by tumor cells and histone lactylation (H3K18lac) in TAMs. Complete success in 100% of mice over tumor control and activation of TAM antitumor phagocytic activity was achieved when Wnt/β-catenin signaling was suppressed by LGK’974 in combination with PI3Ki/MEKi, which resulted in durable tumor control in 100% of the mice via H3K18lac suppression and complete TAM activation [262].

We are only beginning to identify the potential spectrum of enzymes that catalyze the lactylation and delactylation of histones, but the reversibility of this process is essential for considering such enzymes as therapeutic targets. Even more intriguing is the identification of macrophage-specific writers and erasers of lactylation. Identifying which signaling pathway programming the TAM transcriptome can interact with the histone lactylation process is also highly interesting.

Interaction between signaling and epigenetic pathways in the protumoral activation of TAMs

Many signaling pathways in TAMs are known to program their protumoral activities (summarized in [10]). Signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) constitute a family of transcription factors that were originally identified as classic effectors of interferon-induced signaling and are principally involved in macrophage polarization, where STAT1, in response to IFNγ, induces M1 programming, whereas STAT6, in response to IL4, is responsible for the healing of the M2 phenotype [263,264,265,266]. In patients with advanced cervical cancer, an increase in the number of CD68+ pSTAT1+ cells in the tumor mass is correlated with longer disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) [266]. In vitro studies and studies in murine models have demonstrated that STAT3, through the polarization of TAMs to the M2 phenotype, facilitates angiogenesis and tumor progression [267,268,269]. STAT can act cooperatively, and the activation of STAT3 and STAT6 increases cathepsin expression in TAMs, promoting tumor invasion in vivo [264]. IL-4-driven activation of STAT6 inhibited TRIM24 activity, promoting the polarization of macrophages toward the tumor-associated phenotype in a murine model of melanoma [263]. In a murine model of colorectal cancer, activated STAT6 and KLF4 induced M2 polarization of TAMs, leading to tumor progression [265]. TAMs facilitate metastatic colonization via the secretion of IL-35 through the activation of JAK2–STAT6–GATA3 signaling in TAMs, facilitating metastasis in murine mammary carcinoma [270]. This potent role of STATs in M2 polarization resulted in the development of STAT therapeutic inhibitors, and the state of the art for clinical trials is summarized in the last chapter of the review (see Table 3).