Temporal trends in the prevalence of GP registrars’ long-term paediatric asthma control medications prescription

Introduction

Asthma affects 8–10% of children and is the most common chronic illness affecting paediatric patients in industrialised countries1. For general practice (GP) registrars (specialist vocational trainees in general practice/family medicine) in Australia, asthma is in the top ten most commonly seen paediatric presentations2. Asthma is a treatable disease, however 467 people died in Australia due to asthma in 2022, demonstrating room for significant improvements in management3,4.

Long-term asthma control medications (LTACMs)—medicines used in maintenance therapy for asthma—are increasingly seen as a crucial aspect of asthma management. Most prominent among LTACMs are inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs). If not used alone, ICSs are commonly used together with other medicines in LTACM regimens – often in combination inhalers. The importance of LTACMs in asthma management is based on evidence that LTACMs reduce severe asthma exacerbations and resulting asthma-related deaths5,6,7. The importance of LTACMs is reflected in Australian and international asthma management guidelines7,8,9,10,11. The majority of asthma cases both in Australia and internationally are managed in primary care, with specialist referral generally being reserved for asthma that is severe or resistant to management7. GP adherence to clinical practice guidelines for paediatric asthma has been shown to be low, with Australian studies finding GP prescribing for paediatric asthma to be in accordance with evidence-based guidelines in only 40–54% of cases12,13. In addition, GPs’ adherence to asthma guidelines is significantly lower than that of paediatricians12,13. The National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) in the UK in 2012 found that, contrary to guidelines, there was an over-reliance on asthma reliever medications and under-prescription of LTACMs, contributing to poor asthma control and deaths5,14. In particular, there is evidence that the under-utilisation of ICS medications contributes to an overuse of oral corticosteroid medications which over patient lifespans, may result in cumulative toxic-range doses and subsequent metabolic and cardiovascular harms6,15,16. While there is a growing evidence and knowledge base for effective asthma management, many patients are still treated according to outdated principles6.

Australian asthma guidelines have been updated in recent years to reflect the increasing evidence for the use of LTACMs in reducing severe asthma flares, and resulting emergency attendances, hospitalisations and mortality in paediatric asthma7. In 2014 the Australia Asthma Handbook was updated to recommend that most adolescent patients with asthma have regular LTACM treatment with an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS), and further 2020 iterations introduced the new indication for budesonide-formoterol to be used as combination LTACM and reliever therapy in adolescent patients17,18,19. Recent guidelines from the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) Melbourne (extensively accessed by GP registrars around Australia) state that all adolescent patients receiving treatment for asthma should be prescribed an ICS10. The 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) recommendations for primary care state that all children over 5 years should be treated with an ICS medication on a regular or as-needed basis, and recommend against treatment with short-acting beta agonists (SABA) only7. However, at present, guidelines from RCH, Australian Asthma Handbook and Therapeutic Guidelines for children 6–12 still include recommendations for treatment with reliever-only management (short-acting beta agonist; SABA) for certain asthma groups (predominantly those with infrequent asthma symptoms without severe flares)8,11,20 as do UK NICE guidelines21.

Previous research from the UK showed an increase over time in LTACM prescriptions in children between 2006 and 201622. Subsequent LTACM prescribing trends though, may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic—there is evidence from Finland of a reduction in pharmacy dispensing of paediatric asthma LTACMs between 2019 and 2020)23. Little research, however, has been done to assess asthma prescribing trends for children in the Australian setting, or the asthma prescribing behaviours of GP trainees. Registrars are a GP demographic of singular interest in this context: they comprised 15% of the Australian GP workforce (by headcount) in 202224 and are establishing patterns of practice and approaches to therapeutics that may be long-lasting25,26,27.

Given that evidence-based clinical guidelines have increasingly stressed the importance of LTACMs in effectively managing paediatric asthma, it is of interest and of clinical and educational importance to assess how prescribing of asthma preventive medicines by GP registrars has changed over time. In this study we aimed to establish temporal trends in Australian GP registrars’ prescribing of asthma LTACMs from 2010 to 2022.

Results

4393 registrars (95.1% response rate) provided data from 669,160 consultations (and 1,006,141 problems/diagnoses), including data from 2403 registrars who managed paediatric asthma presentations, and a total of 4281 individual paediatric asthma problems/diagnoses (see Table 1 for the characteristics of participating registrars and practices).

For the main analysis, the 4281 asthma problems/diagnoses constituted 3.1% (95% CI [3.0, 3.2]) of all problems in patients aged 1–17 years. Of these asthma problems, an LTACM was prescribed in 1669 problems (39.0%, 95% CI [37.5, 40.5]).

In total, there were 1699 individual prescriptions for an LTACM. The great majority were ICSs (65%) or ICS-LABA combinations (23%). See Supplementary Table 1 for details of the LTACM classes.

For the sensitivity analysis, there were 3,673 asthma problems/diagnoses, constituting 3.5% (95% CI [3.4, 3.6]) of all problems in patients aged 1–13 years. Of these asthma problems, an LTACM was prescribed in 1390 problems (37.8%, 95% CI [36.3, 39.4]).

Main analysis

Table 2 presents the characteristics associated with prescribing LTACMs for paediatric asthma.

Table 3 presents the univariable and multivariable mixed regression model results. There was no significant change in LTACMs prescription with time: OR 1.01 per year, 95% CI [0.98, 1.04], p = 0.57.

The model selection did not remove any variables. The H-L test suggested satisfactory model fit. There did not appear to be any violations of linearity in the log-odds for the continuous variables. The C-statistic for the model was 0.635.

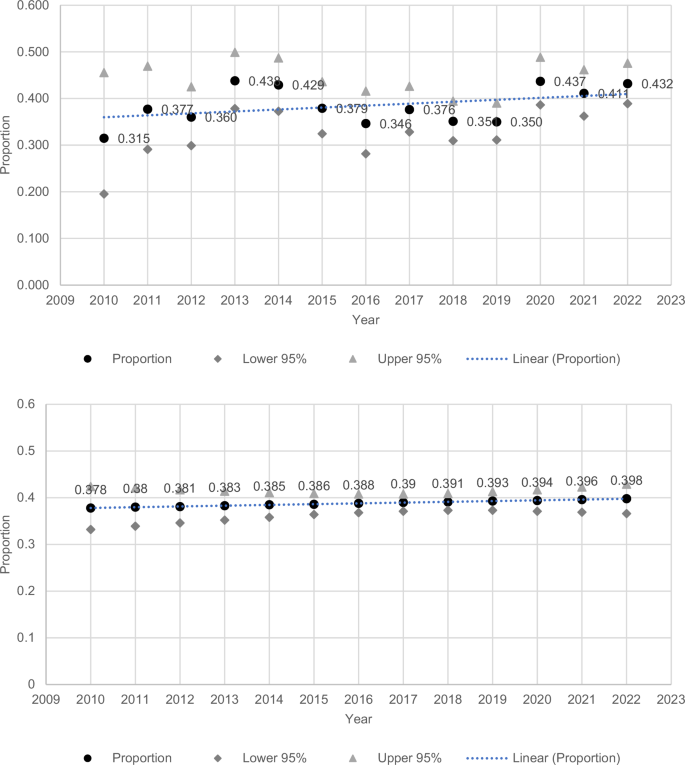

Supplementary Table 2 presents the proportion of LTACMs prescribed by year of consultation (raw and adjusted), and these are presented graphically in Fig. 1. In addition to no long-term trend, there is no effect noted during the pandemic period.

The upper panel displays raw proportions and the lower panel presents adjusted proportions.

Post hoc analysis—trends of prescription of LTACMs by class

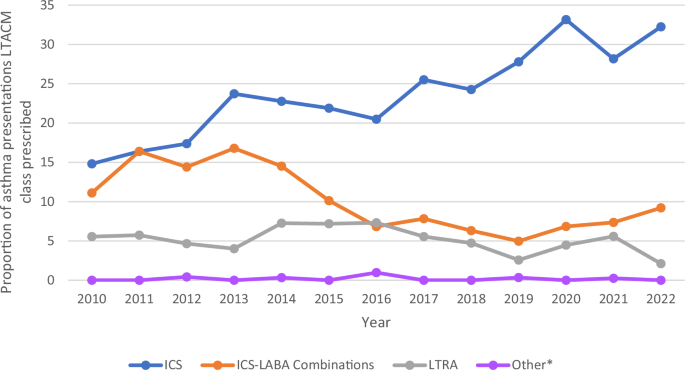

Figure 2 demonstrates univariable findings of the post hoc analysis of trends in prescription of different classes of LTACMs by year, 2010-2022. An apparent increase in ICS prescription appears to be countered by reductions in other LTACMs, particularly LABA-ICS combinations.

Unadjusted temporal trend (2010-2022) in proportion of asthma problems where long-term asthma control medications (LTACMs) were prescribed, by LTACM class *Other medications included cromoglicic acid, nedocromil and omalizumab.

Post hoc analysis—learning goal generation

In the post hoc analysis of learning goals in paediatric asthma, when managing paediatric asthma, registrars generated a learning goal 24% of the time when prescribing an LTACM, and 20% of the time if they did not prescribe an LTACM (Chi square p = 0.010). In comparison, learning goals were generated in 18% of total paediatric problems (compared to learning goals generated in 22% of all paediatric asthma problems/diagnoses, chi square p < 0.001).

Sensitivity analysis

Supplementary Table 3 presents the characteristics associated with prescribing LTACMs for paediatric asthma (ages 1–13).

Supplementary Table 4 presents the univariable and multivariable mixed regression model results. There was no significant change in LTACMs with time: OR 1.01 per year, 95% CI [0.98, 1.04], p = 0.57, with findings very similar to the main analyses.

Discussion

We found no change in GP registrars’ LTACM prescribing in either the 1–17 years or 1–13 years age groups.

Despite there being no overall increase in LTACMs prescribing, different LTACM classes did see changes in prescribing over time. While an increase was seen in the proportion of paediatric asthma consultations where an ICS-only medication was prescribed, this effect was counteracted by a decrease in prescriptions of ICS-LABA combinations plus some decrease in LTRA.

It was also noted in post hoc analysis that registrars were more likely to generate a learning goal when prescribing an LTACM for paediatric asthma. Registrars were also overall more likely to generate a learning goal when managing asthma than when managing other paediatric problems. Previous ReCEnT data has also demonstrated higher learning goal generation when managing paediatric patients than adults28. This suggests that while prescription rates have not changed, paediatric asthma, and specifically asthma prescribing, does appear to be an acknowledged area of learning need for registrars.

LTACM prescription is highlighted in guidelines as a key aspect of good asthma management. Previous research however, suggests LTACMs are underutilised, plausibly contributing to asthma morbidity and mortality5,6,7,12,13,14. A British study examining asthma management found an increase in ICS prescriptions for paediatric patients between 2006 and 2016, seeing primarily an increase in low-dose ICS and, overall, seeing a decrease in asthma patients who were on no ICS treatment22.

There has not been similar research on prescribing trends within Australia or of GP trainees internationally. The lack of temporal trend seen within this research raises the question of whether there are factors specific to the Australian setting, or factors relating to GP registrars, that influence prescribing.

Factors that doctors have reported as barriers to adhering to asthma management guidelines include lack of familiarity or agreement with guidelines for managing asthma, and medication cost29,30. Medication cost in Australia is influenced by Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) reimbursement. Medicines being included or not included in the PBS (or having limitations to which doctors may prescribe them) may influence prescribing. Parental concern regarding the potential side effects of ICS for management of paediatric asthma has been linked to reduced medication adherence31,32,33. Parental concerns surrounding long-term inhaled corticosteroid use have been demonstrated to influence prescribing by some healthcare professionals30. We think it unlikely that any of these factors would have had substantive effect on the temporal trend in our study – and, if so, to have potentially resulted in a temporal change in prescribing, which we didn’t find.

As highlighted, there are some discrepancies seen between asthma management guidelines in Australia and internationally. International GINA guidelines now recommend against SABA-only treatment in children >5 years and adolescents7. Within Australia, RCH guidelines recommend all adolescent asthma regimens should include an ICS10. The Australian Asthma Handbook and Therapeutic Guidelines recommend most adolescents should be on an inhaled steroid, though some with few asthma symptoms and without risk factors may be treated with SABA alone19,34. In children 6–11 years, RCH, Australian Asthma Handbook, Therapeutic Guidelines and UK NICE guidelines step 1 in asthma management is still SABA-only, with the recommendation to step up to LTACM treatment based on symptom frequency and severity8,11,20,21. This may result in SABA-only treatment being considered the default position in asthma management. GPs early in their training are known to have higher levels of uncertainty and concerns around causing patient harm35. This uncertainty could result in registrars being more hesitant to step up asthma management to include LTACMs, potentially contributing to the lack of temporal increase seen in LTACMs prescribing.

The ReCEnT project has a large sample size and very high response rate36. It has good external validity, including participating registrars from six of Australia’s eight states and territories, and capturing data from a variety of levels of rurality, socioeconomic status, and patient demographics. Findings can be generalised to GP registrars in Australia, and external validity will also be strong to other countries with apprenticeship-like GP training structures.

The large number of study factors collected (together with the large sample size) allows for detailed multivariable analyses to account for potential confounding in analyses.

A limitation of this study is that ReCEnT only collects data regarding medication prescribed at the index consultation, and we therefore do not have data on patients’ full medication regimens. A further potential limitation of this study is that our outcome factor is prescribing, not dispensing or actual use, of LTACMs. However, our study focus is on registrar behaviour and adherence to guidelines, so our focus on prescribing is appropriate. While every effort was made to include all ICPC-2 codes that may represent asthma in the study, it is possible some asthma presentations have not been coded as such and therefore are not represented in data. This study is an observational cross-sectional study, and therefore causality cannot be inferred from the findings.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have had effects on the number of presentations of respiratory viruses and therefore asthma presentations from 2020. Evidence suggests a reduction in asthma presentations including reduced exacerbations, hospital admissions, and asthma medications following onset of the pandemic23,37. However, this study assessed proportion of prescriptions, as opposed to numbers of prescriptions, and there was no significant change in prescribing over this time period.

The lack of increase in prescribing of asthma medications for children comes despite updates in authoritative guidelines and messaging to GPs that there should be an increase in use of these medications to effectively manage paediatric asthma. Though their training includes dedicated educational content, Australian GP registrars learn primarily within an apprenticeship-like model in which they are taught and supervised by accredited GPs, with most learning in the practice setting and significant supervisory influence in shaping registrar prescribing38,39,40. It is therefore likely that registrar trends may reflect wider GP prescribing trends. Given the primacy of the practice environment, the findings may also have relevance to the practice of established Australian GPs (at least those in teaching practices). Further research could assess prescribing patterns of qualified Australian GPs and potential barriers in prescribing particular asthma medications.

Given the lack of changes in temporal prescribing trends despite the documented harms associated with LTACM under-prescription, it is clear there should be reflection on the delivery of messaging that GPs and other health professionals receive regarding asthma management. Variability seen between guidelines for asthma management may result in confusion amongst prescribers, and thus our findings may suggest the need for review and harmonisation of guidelines. Our results raise questions of whether guidelines should be more emphatic about the need for the inclusion of LTACMs in managing the majority of children with asthma.

Medical educators may also reflect on the education being provided to GP registrars regarding asthma management – tailored education could be designed for registrars around LTACMs, when to escalate asthma medication treatment and how to respond to potential parental concerns around steroid medications if they are raised in consultation. GP registrars are at a pivotal stage in their vocation where they are establishing clinical and prescribing practices that may persist throughout their career25,26,27.

Despite strong evidence for the need for increased prescription of LTACMs for management of paediatric asthma, no increase in the proportion of LTACMs prescriptions for paediatric asthma by GP registrars was seen between 2010-2022, highlighting the need for further emphasis on paediatric asthma management within general practice education, as well as reviewing potential barriers to prescribing in the GP landscape.

Methods

ReCEnT

A longitudinal analysis of data from the Registrar Clinical Encounters in Training (ReCEnT) study was undertaken. ReCEnT is an ongoing, multicentre inception cohort study that has been collecting data on general practice registrars’ consultations since 2010.

The study protocol is described in detail elsewhere41. GP registrars collect data from 60 consecutive patient consultations in each of their three 6-month (full time equivalent) GP training terms. Over the course of the project, data has been collected in five Australian states and a territory (New South Wales, Victoria, the Australian Capital Territory, South Australia, Queensland and Tasmania) with some discontinuity in regions participating as a result of major structural reorganisations of GP training in Australia. This regional discontinuity was adjusted for in our analyses.

Data collection was previously paper-based (2010-2019), but is now (2020-) collected via an online portal (“ReCEnT online”) utilising electronic case report forms for each consultation. All registrars collect these data as a mandatory part of training (the data informing registrars’ reflective feedback on in-consultation clinical and educational practice)41, and may choose to provide written informed consent to data being used for research purposes. Registrars record data pertaining to their demographics, practice factors, patient factors, and consultation factors (including ‘consultation action’). This study includes data collected during 26 6-monthly rounds of ReCEnT data collection—from 2010 to 202241.

Study population

Patients aged 1–17 years were included in the analyses. The Australian Asthma Handbook states that children less than 1 year of age presenting with wheeze should not be treated as asthma, and is more likely to be attributed to bronchiolitis or laryngomalacia, hence their exclusion from the study population8. The Australian Asthma Handbook defines adolescence as 12–18 years old. However, it also states that from age 14 years, principles of adult asthma management usually apply9. Thus, a sensitivity analysis was undertaken for patients aged 1–13 years old.

An expert group convened from the study investigators, including a GP with long-standing clinical, research and policy expertise in asthma, a paediatrician with clinical and research expertise in asthma, and GP academics, provided advice regarding defining asthma-related diagnoses, age groups used in analyses, and independent variables used in analyses.

Asthma and asthma-related diagnoses were defined by International Classification of Primary Care-2-Plus (ICPC2) codes. Asthma was defined as the following problems/diagnoses defined by ICPC2 codes – R96.1 (asthma), R96.5 (status asthmaticus), R96.2 (asthmatic bronchitis), R96.10 (asthma attack), R49.2 (asthma plan), R49.3 (asthma action plan), R62.29 (asthma care plan), R45.4 (advice and education about asthma). A sensitivity analysis had been planned to also include the codes R96.7 (bronchitis; wheezy), R96.8 (disease, hyperactive airways), R03.1 (Bronchospasm), R50.2 (medication;renew;respiratory), R03.5 (wheeze; expiratory), R04.18 (wheeze;inspiratory), R96.3 (bronchitis;allergic). However, this analysis was not undertaken due to a small number of these problems/diagnoses (60) in the database.

Outcome variable

Our outcome was prescription of LTACMs. LTACMs were defined by Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classifications. Medications classified as LTACMs were glucocorticoids (inhaled corticosteroids – ICS), leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA), antiallergic agents (including cromoglicic acid), combination medications of those aforementioned, and other systemic drugs for asthma prevention (including monoclonal antibody therapies).

Independent variables were included in analyses relating to patient, registrar, practice, consultation and consultation actions. See the content of Table 2 for independent variables included in analyses.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were undertaken at the problem/diagnosis level of all paediatric asthma problems (rather than at consultation level).

The proportion of all paediatric asthma consultations in which an LTACM was prescribed was calculated, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Descriptive statistics included frequencies for categorical variables and mean with SD for continuous variables.

The main analyses used univariable and multivariable mixed effects logistic regressions. The year of consultation was used as the time-related variable. Repeated measures of registrars over time were accounted for through the inclusion of a random intercept for registrar. Year was treated as continuous, and its corresponding parameter estimate represents the estimated change per year in the odds of prescribing LTACMs for paediatric asthma. All other variables were modelled as fixed effects.

An augmented backwards selection process was followed. Variables in the model with p-values > 0.2 were tested for removal. A variable was removed if the resulting model did not have substantively different effect sizes than the previous model. A substantively different effect size was defined as being more than about 10% different to its value in the previous model.

Model fit was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit (H-L) test. The logistic model assumption of linearity in the log-odds for continuous variables was also checked. The model C-statistic was calculated.

For all outcomes, the regressions modelled the log-odds that LTACMs were prescribed. Effects are expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI.

Significance was declared at the conventional 0.05 level, with the magnitude and precision of effect estimates also used to interpret results.

Analyses were programmed using STATA 16.0 and SAS V9.4.

Proportions of asthma problems for which LTACMs were prescribed (with 95% CIs) were calculated for each individual year and presented graphically.

In a post hoc analysis, the temporal trajectories, 2010-2022, of prescription of individual classes of LTACMs were plotted.

In a further post hoc analysis, proportion of paediatric asthma consults where a learning goal (an intention by the registrar to seek information on a particular topic post-consultation) was generated was calculated, for both when an LTACM was and was not prescribed.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses