Text mining of outpatient narrative notes to predict the risk of psychiatric hospitalization

Introduction

The Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation [1] estimated that one in every eight people in the world live with a mental disorder; the most prevalent conditions are anxiety and depressive disorders. Morel et al. [2], noted that 6.7% of all inpatient hospital stays in the U.S. are primarily due to a mental and substance use disorder, and the readmission rates among this patient group are high. In particular, the patients with severe and persistent mental illnesses (SPMI) experience frequent hospital readmissions, which can be a significant cost driver. Soni [3] reported that, in the U.S., the 2019 expenditure for treatment of mental disorders among adults was $106.5 billion, 28.7% of which was spent on emergency room visits and hospital stays. Avoiding hospitalizations, by timely interventions while the patient is receiving community-based care, can be an effective means to mitigate the economic burden of mental health care.

Identifying the patients with high risk of (re)hospitalization is the essential first step of such a preventive mental health care policy. The early literature on predicting hospitalization risk is focused on the use of regression models, whereas the recent literature mostly deploys machine learning (ML) algorithms, showcasing their superior performance. Analyzing 65,000+ mental health and substance abuse patients with 97,000+ admissions, Morel et al. [2] showed that eXtreme Gradient Boosting performs better than regression in predicting readmissions. Their area under the receiver operating characteristic curveFootnote 1 (AUC) for 30-day readmission of this patient group was 0.738. While Blankers et al. [4] also found Gradient Boost to be the best performing algorithm (AUC = 0.774) in predicting psychiatric hospitalization during the first 12 months after a psychiatric crisis care contact, they did not find a major performance difference between the tested ML algorithms. Zhu et al. [5] studied 13,000+ major depressive disorder patients discharged from a hospital. They provided ML-based predictions for a psychiatric readmission within different time windows, where the AUC for 30-day readmission was 0.814.

The recent developments in text mining (and natural language processing) provides us with the ability to extract information from the unstructured free-text fields in the patients’ electronic medical record. Text mining applications in psychiatric research does not have a long history. In their systematic review, Abbe et al. [6], were able to identify only 38 papers, covering a wide variety of topics ranging from the characterization of the patient perspective to treatment side effects. Clinical issues have garnered significant attention, such as predicting psychosis based on speech/language [7,8,9,10,11] and extracting symptoms from clinical notes [12,13,14]. The most relevant stream to this paper is the recent studies on the prediction of early rehospitalization using the hospital discharge narrative notes [15]. Studied a cohort of about 4700 patients with major depressive disorder, 10% of whom were readmitted within 30 days of discharge. They found that it is possible to identify the patients with high risk for psychiatric readmission more accurately by text mining the discharge narrative notes [16]. Studied 5000+ psychiatric admissions to predict the risk of 180-day readmission. Using language-based models based on features derived from hospital discharge notes, they achieved an AUC of 0.726 constituting a notable increase from their baseline model with AUC = 0.675. They also showed that the ML models performed better than experienced psychiatrists for readmission prediction. Interestingly [17], reported that natural language processing methods are not effective on the clinician notes taken during hospital admission in predicting early readmission.

In this paper, we utilize text mining to analyze outpatient narrative notes recorded by psychiatrists in the electronic medical records of patients diagnosed with SPMI. Motivated by the above-mentioned works that found text mining the hospital discharge notes beneficial, we set out to evaluate the potential benefits of text mining the outpatient narrative notes. These free text notes which often capture rich detail and nuance that may be pertinent information for predicting the patient’s risk of rehospitalization. The patient cohort comprises of individuals who have been hospitalized before with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder. This group of patients significantly impact hospital expenditures and overcrowding through frequent emergency room visits, hospital admissions, and readmissions [18, 19]. Our research question is as follows: Is it possible to improve the readmission risk prediction model by controlling for health status extracted from outpatient narrative notes, to better understand the associations between the pertinent variables and readmission?

The hospitalization or re-hospitalization of a patient with SPMI is a complex phenomenon that needs to take into account the following variables: a) the continuity and frequency of outpatient visits including the patient’s adherence to treatment [20]; b) ongoing medication prescriptions and adjustments by psychiatrists [21]; c) the potential existence of a court order requiring impaired patients without adequate insight and judgement to receive LAIs [22, 23]; d) the inherent fluctuations in the course of an individual patients’ illness severity; and e) newly occurring environmental and psychosocial factors in the patients’ life. Thus, the patient-level and system-level factors for a psychiatric readmission are independent variables, whereas the risk of hospital readmission is our dependent variable. By better identifying the SPMI patients with high risk of rehospitalization, we aim to contribute to the advancement of mental health care delivery and alleviate the burden of readmissions on healthcare systems.

Materials and Methods

Data

We conducted a retrospective study of all narrative notes in an SPMI outpatient clinic of a tertiary hospital in Montreal. The study covered the clinic’s all chronically ill patients, without exclusion, from 2016 to 2020. The most frequent diagnoses in the clinic are schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder. The patients visited the clinic every 2–4 weeks to see their psychiatrist and/or receive a LAI from the psychiatric nurse. The mental health care services of each hospital and its outpatient clinics in Montreal are designated to a geographical catchment area. The patients who present at a facility outside the catchment are containing their residence are referred to the facilities in their district. There are virtually no private or alternative mental health services available to this population. These conditions guarantee the integrity of our data, where we have complete and accurate healthcare utilization and clinical records for the patient cohort in this study. No consequential changes in the legal tenets, organizational functioning, bed capacity, or clinic staffing occurred during the study period.

We used demographic and care utilization data for each patent as well as unstructured free-text data contained in the clinic progress notes. The patient-level data includes the dates of all outpatient clinic visits, the dates of administration of LAIs, the presence or absence of CTOs granted by the provincial Superior Court including the dates when they were awarded, the dates and durations of all hospitalizations and the dates of all outpatient and ER visits. During the five-year study period, there were 15,415 narrative notes made on a total of 367 patients. Of this total, 77 patients were under a CTO. Table 1 depicts the characteristics of the CTO and non-CTO patients suffering from SPMI. There are 396 hospitalizations during the study period.

There is a single clinical note taken by the psychiatrist (or psychiatric nurse, psychiatry resident) during each outpatient clinic visits. These were de-identified for the purposes of this research. The outpatient narrative notes are organized according to the commonly used “SOAP” system, where each note is divided into Subjective, Objective, Assessment and Plan fields [24]. Subjective are the patient’s words explaining their current condition. Objective contains the clinician’s evaluation concerning one or more aspects of the patient’s mental status, including appearance, behaviour, speech, affect, thought content, and insight/judgment. Assessment describes the overall status. The Plan section describes treatment medications (including dosage), therapeutic and psychosocial interventions.

In this study, we aim at extracting the “health status” from the Assessment and Objective fields in the clinician notes. The former contains a concise evaluation of the health condition of the patient. While the care provider needs to assess the patient as either “stable” or “unstable”, this is the case for only 56% of the notes. In the remaining cases, the evaluation was expressed by a phrase or a short sentence, which is not always grammatical or clearly understandable; for example, “usual complaintive paranoid”. In our data set, 10.95% of Assessment are empty entries.

The Objective field data is more complex, containing significantly more words than the Assessment field. For instance: “adequately groomed. Pleasant, calm, not hypomanic, no psychosis expressed.” Several aspects of the patient’s mental health condition at the time of the outpatient visit, including appearance, behaviour, speech, thought content, and insight/judgment, are noted by the clinician in the Objective field. The average number of words in Objective is 13.52 (±9:73); the lexical diversity, measured by Type-Token Ratio (TTR), is 0.01.Footnote 2 The low TTR means that the Objective fields mainly consist of a small set of medical terms to evaluate the patient. To provide an intuitive understanding of the low diversity of vocabulary; the top 20 words represent 32% of the whole corpus. In our data, 9.56% of the Objective fields are empty entries.

We observed that there are style differences among the two psychiatrists in the clinic in term of note taking. In the Objective field, for example, psychiatrist B has a richer vocabulary (with 6292 unique words) than psychiatrist A (with 2984 unique words). The latter, however, uses longer sentences with 8.06 words in average, whereas the average sentence length of the former is 4.97 words.

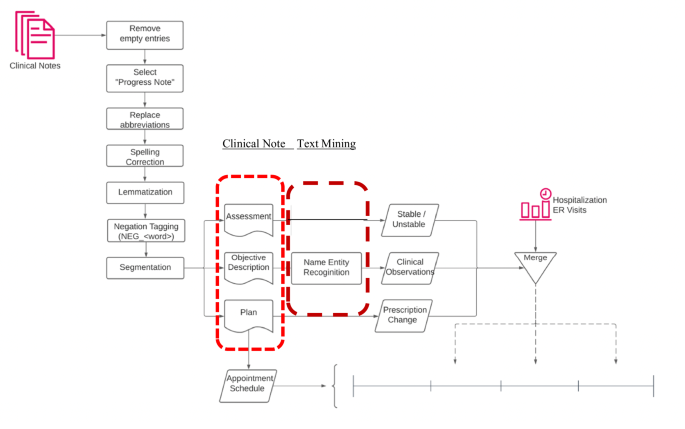

Routine text cleaning and pre-processing procedures are applied, includes removing stopping words, removing special characters, lemmatization, and spelling correction. For negations, we tag all words after both common negation words and medical shorthand negation words. The data processing and analysis flowchart is provided in Fig. 1, which also highlights the pertinent fields of the narrative notes, and the text mining methods deployed for them.

Data processing and analysis.

Mining the Narrative Notes

Appendix B in the online supplement provides five examples for the content of the Objective field. The corresponding values of the confounding variables are also depicted to provide clarity. To automate the processing of the 15,415 narrative notes, we utilized the Named Entity Recognition (NER) model, which played a crucial role in identifying and categorizing keywords within the Objective field. These keywords were classified into one of nine categories: appearance, behavior, danger, impulse control, insight, language, mood, thought content, and thought process. The NER model is an advanced deep convolutional neural network that learns identification rules from annotated training data, enabling it to recognize and categorize entities accurately.

Our approach involved enhancing an open-source pre-trained model known as “ScispaCy” [25], which is designed for identifying medical terminologies. By fine-tuning this model, we extended its capabilities to extract keywords specifically related to psychiatric symptoms observable in patients with SPMI. This fine-tuning process is both data-efficient and computationally inexpensive, allowing for practical and effective keyword extraction in psychiatric contexts. With less than one thousand manual annotations, we achieved a performance of 92.4% precision and 92.5% recall.

The deep convolutional neural network architecture of the NER model enables it to capture complex patterns and relationships within the text, making it highly effective for identifying relevant entities. By leveraging the power of deep learning, the model can handle large volumes of narrative notes, providing accurate and reliable keyword identification that enhances the analysis and understanding of psychiatric symptoms in clinical practice. This automated approach significantly improves the efficiency of processing and analyzing narrative notes.

Estimation of the hospitalization risk

We used a mixed-effect logistic regression model to estimate the likelihood that the patient will be readmitted before the next clinic visit. In our fixed time-period model, the “time-period” was not universal among all the subjects. It was patient-specific, defined according to the patient’s normal frequency of scheduled clinic visits. For example, for patients whose appointments were scheduled three weeks apart, the duration for the fixed time-period was designated as three weeks; and for those who were scheduled to visit every other week, it was designated as two weeks. We used the following representation:

The dependent variable Yi,t+1 denotes the hospitalization of patient i in time period immediately following the clinic visit in time period t. It is a binary indicator, where the value 1 indicates hospital admission and the value 0 indicates no hospital admission during period t + 1. The independent variables are the medical interventions i.e., CTO, LAIs, and prescription changes as well as the patient’s adherence to scheduled clinic visits. We used the following two indicator variables pertaining to CTOs: Before CTO was assigned the value 1 when the patient was not under the CTO intervention during time t but would become under an active CTO later; it took the value 0 otherwise. During CTO was assigned the value 1 when the patient was under an active CTO intervention during time t; it took the value 0 otherwise. Under this variable design, if both Before CTO and During CTO took the value 0, then the patient was a non-CTO patient who was never under any CTO intervention. Clearly, both variables cannot take the value 1 simultaneously.

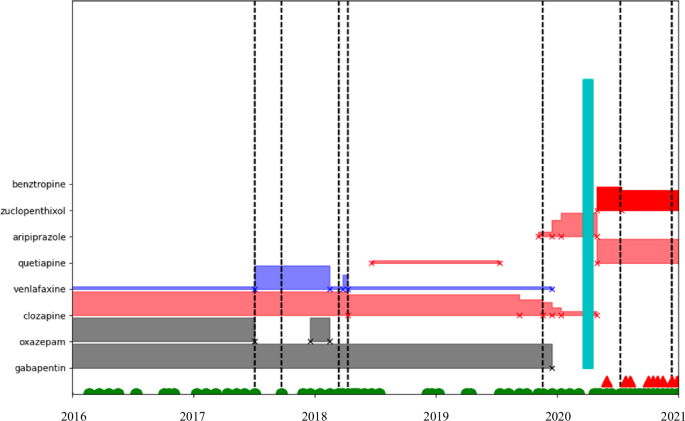

To represent LAIs, the binary variable Injection was assigned the value 1 if the patient was receiving injections at the time-period of interest; and, it took the value 0 otherwise. The binary variable Clinic Visit was assigned the value 1 if the patient followed the appointment schedule and visited the outpatient clinic during period t; it was assigned the value 0 otherwise. The binary variable Prescription Change was assigned the value 1 if the prescription was changed in the current time-period; it was assigned the value 0 otherwise. This information is collected from the Plan field. To illustrate, Fig. 2 shows the timeline of medical events for a patient. Vertical dotted lines indicate ‘unstable’ notes; green vertical blocks indicate hospitalizations; horizontal blocks indicate the prescription for the patient during a certain time-period; the name of each medication is shown on the y axis; the height of the horizontal block represents dosage for the medication. This specific patient was under a combination of psychiatric medications, had several ‘unstable’ moments, had several prescription changes; and, had one hospitalization. As we can observe from Fig. 2, the prescription was changed in the middle of 2017 at the first ‘unstable’ assessment; but the prescription was not changed at the second ‘unstable’ assessment. Nevertheless, there was no hospitalization until 2020, and the patient remained largely stable during that year. At the end of 2020, however, the patient had become ‘unstable’ – the prescription was changed, and the patient was hospitalized not long afterwards.

Timeline of medical events for a patient.

In our model, Treatment Dropout is a binary indicator variable, where the value 1 indicates that the patient missed more than three sequential appointments and the value 0 indicates otherwise. For SPMI patients, we considered treatment dropout as a strong indicator of elevated hospitalization risk. Missing appointments were measured via the clinic appointment schedule and with leniency. For example, if a patient is on a two-week schedule for the next appointment, a missing appointment was documented after the patient did not show up in three weeks; if a patient was on a four-week schedule, we utilized a six-week period to declare missing an appointment. Lastly, Hospital Discharge was employed as a binary variable with the value 1 indicating the patient was discharged from the hospital in the current period and 0 otherwise. We did not consider the time spent during the hospital stay, as this study only focuses on the risk of re-hospitalization during outpatient care.

The “health status” of a patient during period t can be correlated with both the medical interventions in t (i.e., CTO, LAI, prescription change) and the health outcome in t + 1 (i.e., re-hospitalization). Therefore, the patient’s health status is represented using a set of confounding variables (i.e., the second last term in the model above) extracted from the outpatient narrative notes through text mining. ({beta }_{10}) and ({beta }_{11}) are the coefficients for the binary variables Stable and Ustable, indicating the patient’s condition. Stable takes the value 1 when there is the word “stable” in the Assessment field, and Unstable takes the value 1 when there is the word “unstable”. Thus, both variables being zero would indicate that either there are other words, or the field is empty. The variables extracted from the Objective field include the patient’s appearance, behaviour, danger, impulse control, insight, speech, affect, thought content, and insight/judgment. Please see Appendix A in the Online Supplement for the formal definitions of these confounders.

While the confounding variables may not be independent of other, this does not affect the analysis of the effects of interventions or treatment dropout. Although the confounding variables are not the primary focus of this study, it is noteworthy to observe their relationships. The table in Appendix C (see online supplement) illustrates these associations. Since patients are assessed as stable during majority of the clinic visits, the positive aspects of the confounding variables often co-exist in the Objective field. Interestingly, there is also a moderate association between the positive and the adverse variables, reflecting the complexity of patients’ mental state. Focusing solely on the relations among the negative aspects of the confounding variables, adverse mood and adverse thought content emerge as the most strongly associated factors. We have deliberately refrained from further interpreting the relationships between confounding variables, as the primary aim of incorporating these text-mining-based variables is to evaluate whether they enhance the prediction of medical intervention effects and treatment dropout on hospitalization risk for SPMI patients.

Results

Text-mining words for predicting clinical course

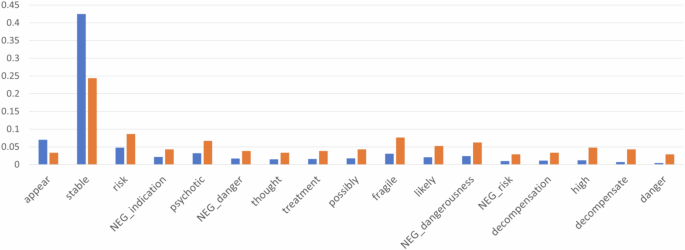

Text-mining of the outpatient clinical notes demonstrated a statistically significant impact of the appearance of certain words, such as “stable”, with the risk of an upcoming hospitalization. The word “stable” was much more likely to appear in notes taken at clinic visits not preceding hospitalizations. The proportion of clinician notes with a “stable” assessment reduced significantly from 56.5% during visits not preceding a hospitalization to 29.5% during the last clinic visit before hospitalization. Conversely, Fig. 3 also depicts the increase in the use of “risk”, “psychotic” and “fragile” during the clinic visit preceding hospitalization. Figure 3 provides more detail on the words that appear in the Assessment field.

Histogram of the words in assessment field  .

.

Predictive model improvement via text-mining

Table 2 shows the analytical results on the effect of several medical interventions and treatment dropout on hospitalization risks. This is a mixed effects analysis with individual random effects. Model (1) does not control for the patient’s health status represented by features extracted from the clinical notes; whereas Model (2) controls for the health status. The log-likelihoodFootnote 3 metric depicted in Table 2 reveals that Model (2) is more accurate in estimating the variable coefficients and embodies a higher confidence in causation inference. We also report the Akaike and Bayesian information criteria in Table 2. It is well known, however, that both criteria penalize models with larger number of parameters. Since Model (2) has many more parameters than Model (1), these two criteria are not suitable for comparing our models in terms of their fit to data.

Having fewer parameters, it is anticipated that model (1) would overestimate (or, underestimate) some coefficients. This could happen due to (i) omitted variable bias and (ii) model misspecification. Pertaining to (i), the coefficients of the included variables may pick up the effect of those missing variables. Concerning (ii), the simpler model may lack flexibility and fail to capture underlying patterns in the data. These imply that the confounders we extract using text mining, and add to model (2), are indeed essential variables. Thus, model (2) seems to better capture the interactions among the parameters and explain the variation in the data.

To illustrate the impact of controlling for health status, we focus on the coefficient estimates for Prescription Change. Model (1), not controlling for health status, shows a strong positive correlation between prescription changes and hospitalization risks. In comparison, in Model (2) with controls for health status, both the coefficient estimate and its significance level decrease for Prescription Change. Because both prescription change and hospitalization can be correlated with health deterioration, Model (1) fails to account for this confounding effect and provides less reliable results than Model (2).

As expected, Model (1) suggests that a clinic visit would reduce the risk of hospitalization. It is surprising, at the outset, to see that Clinic Visit has an increasing impact in Model (2). Note, however, that the variable Stable seems to have taken over the risk reducing impact in Model (2) –and the patients are stable during a significant majority of the clinic visits. Model (2) reveals that a stable Assessment, and positive comments on thought content in the Objective field reduce the hospitalization risk in a statistically significant manner. Whereas negative comments on language in the Objective field have a statistically significant increasing effect on the risk of hospitalization. We experimented with three additional models that drop different combinations of the statistically significant confounders, but neither of them performed better than Model (2).

Impact of psychiatric interventions on hospitalization risk

Our analytical results via Model (2) both conform with the prevailing scholarly literature and yield additional insights. Consistent with the literature, Table 2 shows that CTO patients have a much greater risk of hospitalization before the CTO, increasing the odds of hospitalization by exp(2.114) = 8.281 times on the average. The elevated hospitalization risks decrease during CTO interventions, but the risk is still higher than non-CTO patients. Long-acting injections could cut down the hospitalization risks by almost half i.e., exp(−0.708) = 0.458 times. In addition, there is a higher risk of hospitalization right after hospital discharges, as Hospital Discharge increases the odds of re-hospitalization by exp(2.520) = 12.428 times. This corresponds to the revolving door phenomenon in clinical practice i.e., frequent readmission of discharged patients. As expected, treatment dropout considerably increases the odds of hospitalization by exp(1.317) = 3.732 times with a strong statistical significance. A quick comparison of the estimated coefficients in the two models reveals that Model (1) overestimates the impact of CTOs and LAIs on the hospitalization risk, whereas it underestimates the impact of a hospital discharge and treatment dropout.

Discussion

Recent publications suggested that psychiatry would be ill-advised to ignore the benefits of numerical analysis methodologies and continue relying on the traditional subjective and quasi-objective methods, such as rating scales [26, 27]. Text-mining is among the fledgling approaches that can be leveraged to better understand psychiatric phenomena and treatment. It has not yet had a major impact on clinical practice but portends to do so going forward. We demonstrate that text-mining could also assist with understanding and possibly mitigating presently dysfunctional care utilization patterns. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to utilize this methodology in studying the course of illness and treatment utilization patterns in seriously ill psychiatric patients. While the association between words such as “stable”, “danger” and “risk” appearing in clinical notes and an increased risk of re-admission makes clinical and logical sense, the primary finding of this paper is the value of text-mining in improving predictive accuracy concerning readmissions.

Clinical note text mining is not without drawbacks. The text analysis relies on understanding the text itself; natural language processing techniques do not have medical training in deduction and diagnostics. Thus, the understanding of clinical notes is more than a simple reading of collection of symptom descriptions. But this is not a cause for pessimism for the text mining approach. The health status extracted from the clinical notes acts as a confounding variable. This means we do not seek a perfect representation of illness status- instead, we seek representations highly correlated with the underlying illness status. Further, and as could be expected, clinical notes by different clinicians have different styles. The most noticeable difference is the level of detail contained in the notes. However, we may argue that crucial information is present despite the conciseness of the note.

Current research emphasizes the importance of continuous outpatient follow-up visits. Our findings reinforce the conclusion that missing appointments increase deterioration risks, and regular outpatient visits are essential in preventing rehospitalization. Indeed, the main objective of a CTO is to improve adherence to clinic visits and treatment. Nonetheless, we believe that perhaps there can be less restrictive measures than a CTO to prevent treatment dropouts. Devising policies for improving clinic visit adherence constitutes a fruitful avenue for future research.

Emerging technologies in artificial intelligence, such as text-mining, present promising opportunities for psychiatric care utilization research. Our study reveals that it is possible to strengthen the predictive performance of classical models by incorporating confounders extracted from outpatient narrative notes via text mining. This opens the door for the development of more effective interventions and policies to mitigate psychiatric readmissions.

Responses