The availability of drugs for stable COPD treatment in China: a cross-sectional survey

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is currently one of the leading causes of death worldwide1,2. The total prevalence of COPD in China was 8.6% (95% CI 7.5–9.9)3, and the global prevalence of COPD among people aged 30–79 years was 10.3% (95% CI 8.2,12.8)4,5. COPD causes approximately three million deaths annually, 90% of which occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)6. COPD also imposes a significant macroeconomic burden that is unevenly distributed among different geographical locations and socioeconomic levels7. However, a significant missed opportunity of COPD treatment has been reported in LMICs, highlighting the need to understand and improve the current conditions of COPD management8,9.

According to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines 2023 and Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of COPD (revised version 2021), management approaches of COPD include pharmacological treatments, smoking cessation, vaccination, pulmonary rehabilitation and education of patients10,11. Among these approaches, pharmacological treatments were regarded as the cornerstone of COPD management, as these drugs are beneficial for reducing lung function decline and mortality rates11. However, the availability of drugs for COPD varies across different geographical locations12,13,14. In 36 countries studied across WHO regions, the average availability of generic salbutamol inhalers was 29% in the public sector and 61% in the private sector15. In Southeast Asia, the public sector had the lowest mean availability at 5%15. Another recent systematic review showed that the availability of inhaled corticosteroid–long-acting β-agonist (ICS-LABA) was lower than 80% in four countries16. All these studies suggested that the availability of drugs for patients with COPD was still a challenge to address.

Furthermore, the Chinese population has been suffering from inaccessible and unaffordable health care for decades17. In Zhejiang Province, one of the top five provinces in China in terms of economic development, the availability of 50 essential medicines is low in the public and private sectors, and the availability of salbutamol inhalers in public and private pharmacies is 70% and 40%, respectively18. However, there is still limited evidence on drug availability for stable COPD treatment in China. This survey aimed to investigate the availability of both inhaled and oral drugs for stable COPD treatment across Chinese hospitals with different characteristics, which may provide another perspective over the current challenges and potential solutions in stable COPD management.

Methods

Drug list for COPD patients

Drug selection of this survey was conducted based on the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (revised version 2021)10. Twenty-three kinds of drugs, ranging from inhalation drugs (monotherapy, double therapy and triple therapy) to oral drugs (expectorants, theophylline, antibiotics and bacterial lysates), were included in this survey (Table 1).

Survey design and data collection

A questionnaire was used to conduct this cross-sectional survey from March 2023 to December 2023. The questionnaire was composed of three parts: (1) Baseline information of the hospital, including level (primary/secondary/tertiary/temporarily uncertain), public or private status, establishment of an independent respiratory department (yes/no), number of beds and doctors in the respiratory department, and establishment of a respiratory outpatient (yes/no). (2) Availability of different kinds of inhalation drugs (yes/no). (3) Availability of different kinds of oral drugs (yes/no). Doctors who worked in different hospitals in China completed the survey via WeChat19. The website Wenjuanxing (https://www.wjx.cn/) was used for data collection. Invalid responses were defined as follows and excluded from further analysis: (1) Duplicate responses providing drug availability data of the same hospital. If two or more responses from the same hospital were received, we contacted this hospital for the most accurate response and removed the others. (2) Incomplete answers to questions. (3) Responses from specialized hospitals which are not responsible for COPD management, such as children’s hospitals and psychiatric hospitals.

Statistical analysis

Availability of all categories and all kinds of drugs was analyzed. The drug categories included short-acting β2 agonist (SABA), long-acting β2 agonist (LABA), short-acting antimuscarinics (SAMA), long-acting antimuscarinics (LAMA), LAMA/LABA, ICS/LABA, and ICS/LAMA/LABA, expectorants, theophylline, antibiotics and bacterial lysates (Table 1). Availability of drug category was defined as having at least one kind of drug within each category (e.g., Hospitals having either terbutaline or salbutamol were regarded as SABA available). Availability of each kind of drug was defined as having the particular kind of drugs (e.g., Hospitals having terbutaline were regarded as terbutaline available). Subgroup analyses were then conducted to determine the availability of drugs in hospitals with different characteristics. Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages) and were analyzed using the chi-square test. All the data were analyzed and presented using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corporation) and GraphPad Prism 8.0.

Results

Baseline characteristics of hospitals

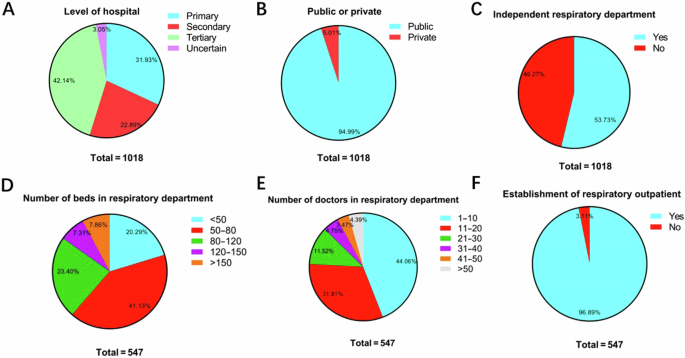

A total of 1425 responses to the questionnaire were ultimately returned, and 1018 hospitals (94.99% are public hospitals) from 31 provinces were enrolled after excluding invalid responses. The geographic distribution of the enrolled hospitals was presented in supplementary materials (Table S1). For baseline information, primary, secondary and tertiary hospitals comprised 31.93%, 22.89% and 42.14%, respectively. A total of 547 (53.73%) hospitals established independent respiratory departments, most of which also established respiratory outpatient departments (96.89%). Among them, respiratory departments with 50–80 beds (41.13%) or 1–10 doctors (44.06%) accounted for the largest proportion (Fig. 1).

A Level of hospitals (n = 1018). B Public or private hospitals (n = 1018). C Establishment of independent respiratory department (n = 1018). D Number of beds in the respiratory department (n = 547). E Number of doctors in the respiratory department (n = 547). F Establishment of respiratory outpatient (n = 547).

Overall availability of drugs for COPD treatment

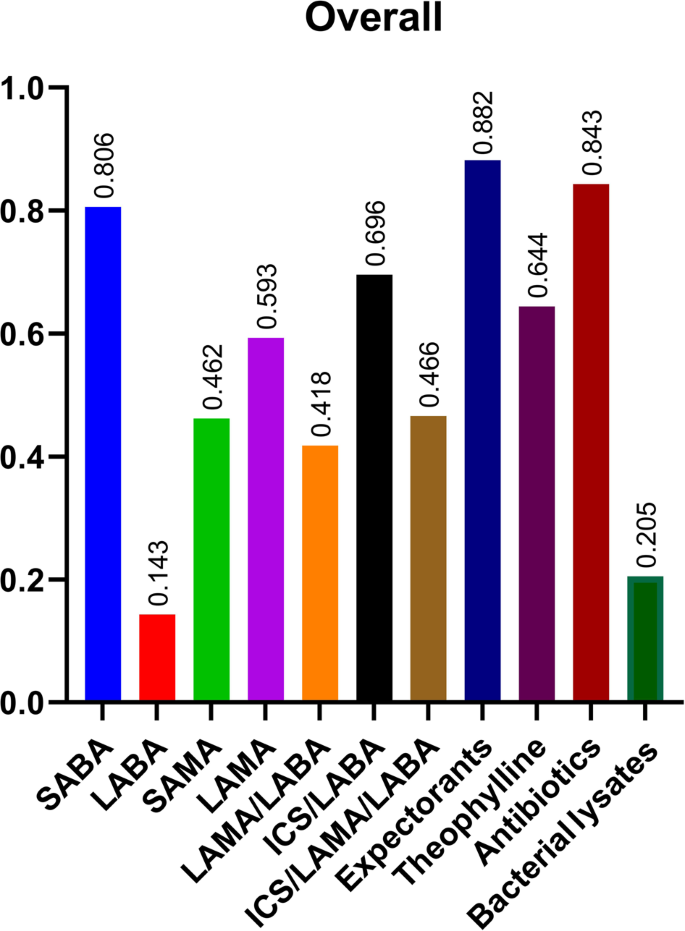

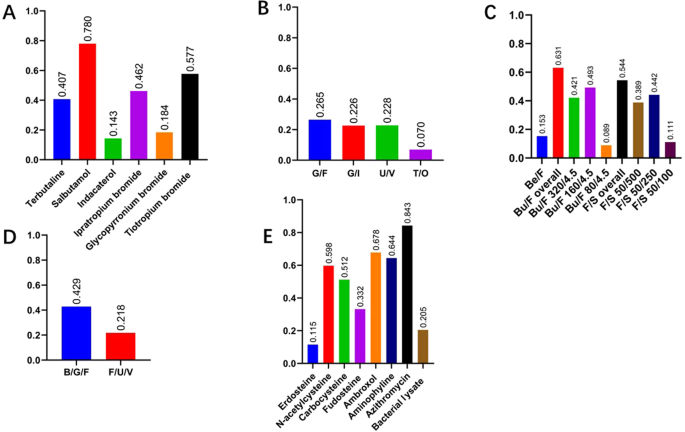

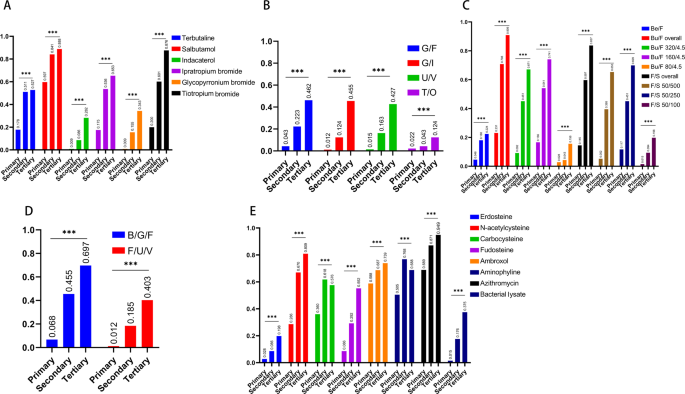

The overall availability of all categories of drugs were presented in Fig. 2, suggesting insufficient supply of all COPD-related drugs, with only short-acting β2 agonists (80.6%), expectorants (88.2%) and antibiotics (84.3%) reaching 80%. The overall availability of each kind of drug was summarized in Fig. 3. Salbutamol (78.0%), glycopyrrolate/formoterol (G/F) (26.5%), budesonide/formoterol (Bu/F) (63.1%), budesonide/glycopyrronium/formoterol (B/G/F) (42.9%) and azithromycin (84.3%) reached the highest percentages among the monotherapies, LAMA/LABA, ICS/LABA, ICS/LAMA/LABA and oral drugs, respectively. The availability of all kinds of drugs in different levels of hospitals was presented in Fig. 4, which showed that the availability of all kinds of drugs in primary hospitals was significantly poorer than that in secondary and tertiary hospitals (all p < 0.001). Although inhaled drugs play essential roles in management of COPD patients, most inhaled drugs did not reach an availability of 20% in primary hospitals, except for salbutamol (59.7%), tiotropium bromide (20.0%) and beclometasone/formoterol (23.1%).

SABA Short-acting β2 agonist, LABA Long-acting β2 agonist, SAMA Short-acting antimuscarinics, LAMA long-acting antimuscarinics, ICS Inhaled corticosteroids.

A Monotherapy; B LAMA/LABA; C ICS/LABA; D ICS/LAMA/LABA; E oral drugs. SABA short-acting β2 agonist, LABA long-acting β2 agonist, SAMA short-acting antimuscarinics, LAMA long-acting antimuscarinics, ICS inhaled corticosteroids.

***p < 0.001. A Monotherapy; B LAMA/LABA; C ICS/LABA; D ICS/LAMA/LABA; E oral drugs. SABA short-acting β2 agonist, LABA long-acting β2 agonist, SAMA short-acting antimuscarinics, LAMA long-acting antimuscarinics, ICS inhaled corticosteroid.

Subgroup analyses

Results of a more detailed subgroup analyses for drug availability in hospitals with different characteristics were presented in Tables 2–3. The availability of all categories of drugs differed significantly among different hospital levels (primary/secondary/tertiary/temporarily uncertain) (all p < 0.001) and the establishment of a respiratory department (yes/no) (all p < 0.001). However, few differences in drug availability were observed between public hospitals and private hospitals, except for SAMA (p = 0.032). Furthermore, for hospitals with an independent respiratory department, the availability of most drugs differed among departments with different numbers of beds, except for SABA (p = 0.181), theophylline (p = 0.133) and antibiotics (p = 0.061) (Table 3). The availability of most categories of drugs was also different among departments with different numbers of doctors, except for SABA (p = 0.369), ICS/LABA (p = 0.140), expectorants (p = 0.350), theophylline (p = 0.138) and antibiotics (p = 0.337).

Discussion

Drug availability serves as the cornerstone of chronic disease management. This cross-sectional survey investigated the availability of drugs for COPD treatment from 1018 Chinese hospitals with valid responses. Results of this survey suggested that the availability of drugs recommended for COPD treatment is still insufficient, and a significant availability gap still exists among hospitals at different levels. This survey also suggested that drug availability can be associated with multiple factors, including the establishment of respiratory departments, the number of beds in respiratory departments, and the number of doctors in respiratory departments.

Current evidence suggests an unmet therapeutic opportunity for COPD patients in LMICs, highlighting the importance of drug availability and sustainability in COPD management8,9. Zeng et al. noted that more than 30% of COPD patients were following inappropriate pharmacological therapies in a multicenter study20. Yang et al. reported that more than 10% of COPD patients with a high risk of exacerbation (GOLD group E) never received any long-acting inhaled drugs21. One potential cause for the above conditions may be attributed to insufficient essential drug supply16. Previous studies have reported the availability of COPD essential drugs in multiple LMICs around the globe. Stolbrink et al. noted that only 6 of 58 LMICs reached a SABA availability of 80%16. Plum et al. reported an ICS/LABA availability of 37.8% in 13 African countries22. Ozoh et al. also demonstrated the limited availability and affordability of COPD essential medicine in Nigeria23. Consistent with previous findings, results of the survey showed that there is lack of adherence to the National and Global COPD guidelines in the stable COPD management practice in China.

Furthermore, the significant gap of basic medical services among primary, secondary and tertiary hospitals cannot be ignored24. Previous studies have shown that patients treated at different hospital levels were associated with different levels of health education, healthcare quality and mortality rates24,25. Mao et al. reported that COPD patients in primary and secondary hospitals were characterized by a lower rate of pulmonary function examination and poorer use of inhaled drugs than those treated in teaching hospitals26. Results of this survey showed that drug availability for COPD patients was also significantly different among hospitals at different levels, and none of the drugs reached an availability of 80% in primary hospitals. These findings are consistent with previous studies, as insufficient and uneven essential drug supply for other chronic diseases like hypertension and dyslipidemia have already been reported27,28. One potential reason for the availability difference between primary hospitals and secondary/tertiary hospitals may be insufficient funding of primary care settings, which warrants further investigations.

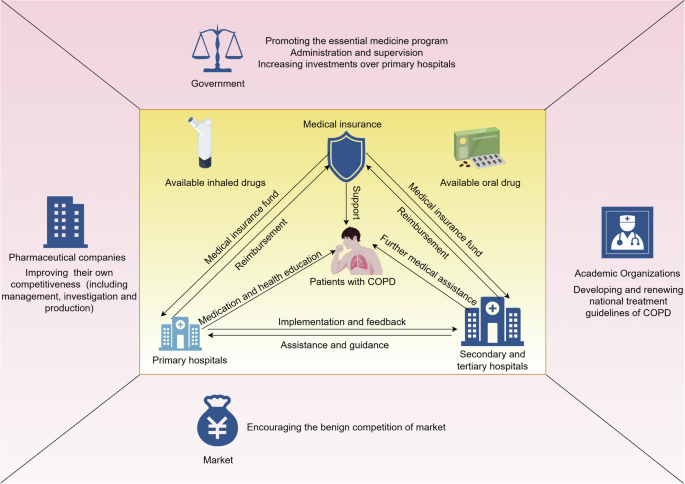

The potential methods for improving the poor availability of COPD-related drugs to improve the quality of COPD management are summarized in Fig. 5, calling for stronger collaboration among multiple aspects29. The government, who are responsible for administration and supervision, needs to promote essential medicine programs. The government may also increase investments in primary hospitals to improve their healthcare quality and drug availability, as a large proportion of patients with COPD may seek for treatment in primary care settings30. Pharmaceutical companies may improve their competitiveness by placing emphasis on the management, investigation and production of drugs. Academic organizations may focus on developing and renewing treatment guidelines for COPD, which is beneficial for renewing essential medicine lists and improving the overall quality of COPD management. The benign competition within the market should also be encouraged to maintain drug quality and stimulate innovations. With the improvement of drug availability via the above methods, primary hospitals may provide sufficient medications and health education to patients with COPD. Primary hospitals may also receive assistance and guidance from more advanced hospitals in the management of stable COPD. Secondary and tertiary hospitals receive feedback from primary hospitals and provide further medical assistance to patients in need. Medical insurance departments may provide funding to all levels of hospitals and reduce the medical expenditure of COPD patients.

Created by figdraw.

This survey also has some limitations. (1) Although this survey was conducted based on hospitals from 31 provinces, considerable variation has been revealed in the number of hospitals from different provinces in China, which may make the results less representative and cause potential bias. (2) In this survey, tertiary hospitals comprised 42.14% of the total sample; whereas in reality, the proportion of tertiary hospitals in China was less than 15% (Data source: The State Council of the People’s Republic of China). Although we conducted subgroup analyses to investigate drug availability in hospitals with different levels, this may still introduce potential bias to our results. (3) The guidelines for COPD are updated rapidly, and China has released a new primary care guideline in 202431, leading to updated medication information as well. Future studies may follow the newest guideline to update our results.

Taken together, our results found that the availability of drugs for stable COPD treatment is still an ongoing challenge for healthcare institutions in China. Insufficient supply of inhaled drugs and imbalanced drug availability among different levels of hospitals are major barriers that warrant further improvements.

Responses