The development and application of an engineered direct electron transfer enzyme for continuous levodopa monitoring

Introduction

Parkinson’s Disease (PD) impacts more than 1 million people in the United States and is expected to rise due to an increasing aging population. PD is characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and the widespread accumulation of aggregated α-synuclein proteins, known as Lewy bodies, in neurons1,2,3. PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that has no cure or disease-modifying therapy, and patients are typically treated with levodopa, a dopamine precursor capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier and alleviating motor symptoms. To improve the uptake of levodopa from plasma through the blood-brain barrier, it is generally co-administered with either carbidopa or benserazide. These compounds, which are blood-brain impermeable, inhibit aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase, reducing the peripheral metabolism of levodopa to dopamine4,5,6. Once inside the brain, levodopa can be oxidized into dopamine supplementing endogenous concentrations.

Fluctuations in the effects of levodopa outside the therapeutic range can lead to significant side effects, including ‘off-time’ periods when the medication effects wane, causing the return of debilitating symptoms. Additionally, if too much levodopa is given, patients can experience levodopa induced symptoms, including nausea and dyskinesia. Due to this tight therapeutic window, real-time monitoring of levodopa could pose great value, leading to more precise dosing, resulting in lower levodopa variability and maximizing time spent in the therapeutic range. Additionally, continuous levodopa monitoring could also enhance our understanding of the pharmacokinetics of levodopa and the influence of multiple factors on these dynamics enabling clinicians to better treat patients7. The most widely used application of continuous monitoring is seen in diabetes management where the use of continuous glucose monitors has not only enabled predictive closed-loop therapy improving patient outcomes but has also enhanced our theoretical understanding of glucose-insulin dynamics8. We anticipate that the development of a continuous levodopa sensor will have a similar impact on PD management, particularly in advanced stages of the disease. This development in levodopa monitoring is not only critical for reducing periods of symptom resurgence but also for deepening our insight into the drug’s pharmacokinetics across various tissue compartments, ultimately improving PD management.

Despite the potential benefit offered by levodopa monitoring in PD management, there is not yet a commercially available continuous levodopa sensor. Various efforts to develop levodopa sensors have explored two fundamental approaches: the direct oxidation of levodopa’s hydroxyl groups and the use of tyrosinase to catalyze the oxidation of levodopa into dopaquinone6. Direct oxidation of levodopa is achieved due to its electrochemical reversibility, where it is directly oxidized at potentials greater than 0.34 V (vs Ag/AgCl) into dopaquinone. Numerous methods have been developed to enhance specificity and sensitivity for direct oxidation, as shown in Table 1. While these methods offer enhanced stability by not requiring biological components, they are inherently limited by poor specificity. Solid-state electrode surfaces lack the intrinsic specificity required for in vivo detection, which has prevented the widespread use of direct oxidation methods for in vivo applications. Alternatively, tyrosinase-based sensors allow for levodopa detection primarily through oxidizing levodopa, an o-diphenol, into o-quinones (dopaquinone). However, similar to direct oxidation strategies, tyrosinase exhibits poor substrate specificity, as many levodopa metabolites and key interferents cross-react with it, as shown in Supplementary Figure S1. The limitations of direct oxidation and tyrosinase-based systems continue to hinder the development of continuous levodopa sensing, necessitating the use of alternative strategies such as a levodopa specific enzyme that is capable of direct electron transfer (DET) between the enzyme and electrode surface.

Enzymes capable of DET have been demonstrated to be ideal for use as molecular recognition elements in biosensors, particularly in continuous monitoring systems. DET enzymes excel because they do not rely on ambient oxygen or co-immobilized synthetic electron acceptors (mediators) for electron transfer9,10. This requires fewer essential reactions of monitoring when compared with first- and second- generation enzymatic sensors, further simplifying sensor design. In addition, enzymes which require oxygen to act as an electron acceptor face many challenges when used in vivo for extended periods of time as the local oxygen concentration will change due to physiological processes around the sensor11,12. DET enzymes’ independence from external mediators is particularly advantageous as electron transfer between DET enzymes and the electrode surface will only occur if sufficient overpotential is applied. This reduces the impact of endogenous and exogenous interfering substrates, as the shift from thermodynamically unfavorable to favorable is governed by Gibbs free energy and the Nernst equation13,14. These benefits have led to DET enzymes being integrated into various enzymatic electrochemical sensing architectures, such as chronoamperometry15,16,17,18 and potentiometry19,20,21,22,23. Two challenges with using DET type enzymes are the limited number of enzymes exhibiting DET capabilities and the electron transfer rate between the enzyme’s electron transfer subunit and the electrode. This rate is governed by Marcus theory, exhibiting decay with increasing distance24.

Among various DET enzymes, multicopper oxidases (MCOs) have been utilized as DET-type cathodic enzymes for enzymatic fuel cell systems. MCOs can accept and utilize electrons directly from electrode, which are derived from enzymatic anodic reactions such as glucose oxidation and then catalyze the reduction of oxygen into water. MCOs contain four copper atoms, with the copper-binding centers being categorized as type 1 (T1), type 2 (T2), and type 3 (T3). MCOs facilitate the oxidation of various substrates, including aromatic phenols, amines, and metal ions by reducing their T1 copper (reductive half reaction) and the subsequent tetra-electron reduction of molecular oxygen by oxidizing reduced copper atoms in T2/T3 coppers (oxidative half reaction) to water. In MCOs, the mononuclear T1 center can not only accept an electron from the substrate but can also accept an electron from the electrode. This electron is then transferred to the trinuclear T2/T3 center, where molecular oxygen is reduced to water. This oxidoreductase activity of MCOs have been used in a variety of biofuel cells and sensor configurations across a range of applications25,26,27. Although MCOs utilize oxygen as an electron acceptor to oxidize phenolic compounds, their use as anodic enzymes for enzymatic sensors is limited. This limitation is attributed to two main reasons: first, the water-forming reaction of MCOs during oxygen reduction can only be monitored by detecting a decrease in oxygen concentration; second, there is a lack of any reported alternative electron acceptors other than oxygen. One of the MCOs, derived from hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrobaculum aerophilum, McoP, was elucidated and demonstrated extraordinary stability28,29. After a directed evolution strategy, an engineered McoP featuring a Phe290Ile mutation, showed an approximately 12 -fold increase in catalytic activity when compared to the wild type McoP, while maintaining the same thermal and pH stability of the wild type. We have utilized this engineered McoP as an anodic enzyme to construct an enzyme fuel cell that utilizes phenolic compounds derived from glutaraldehyde as a fuel source30. However, McoP’s ability to utilize oxygen as the primary electron acceptor still limits its DET-type biosensing application.

We serendipitously found that McoP exhibited high specificity towards levodopa. Therefore, we focused on McoP’s superb substrate specificity compared to tyrosinase. Subsequently, we engineered this enzyme to not use oxygen as an electron acceptor, converting it into a DET-type dehydrogenase enzyme suitable for continuous levodopa monitoring. In the present work, we first demonstrate how McoP can be converted into an oxygen insensitive DET-type dehydrogenase enzyme by introducing mutations to the ligands for the T2/T3 coppers. This engineered McoP does not harbor T2/T3 coppers and only contains the T1 copper, thereby reducing the use of oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor while still keeping its DET-ability by retaining the T1 copper. We designated this engineered McoP as a copper dehydrogenase, CoDH. Next, we introduce the application of CoDH as a DET-type chronoamperometric enzymatic sensor that is suitable for continuous levodopa monitoring. The levodopa sensor was initially characterized on gold disc electrodes with CoDH immobilized on the electrode surface via a self-assembled monolayer (SAM). We assessed the impact of 18 enzymatic interferents on the chronoamperometric signal, including a range of dopamine analogues, key dopamine metabolites, and common molecules found in interstitial fluid and plasma. For subsequent experiments, gold microwires were used to create a miniaturized levodopa biosensor suitable for subcutaneous insertion. The miniaturized levodopa sensor was then evaluated across the physiological range of cerebrospinal fluid and venous plasma in buffer, demonstrating its feasibility to develop in vivo, real-time, continuous levodopa monitoring. This is the first report of an oxygen-insensitive mutant MCO enzyme harboring DET activity and the first among published works on levodopa biosensing to include such a diverse range of molecules in the interferent study.

Results

Development of DET-type enzyme for levodopa sensing

Figure 1a illustrates the scheme for the reductive and oxidative half-reactions of the F290I McoP. McoP catalyzes the reductive half-reaction by oxidizing levodopa with T1 copper and then transferring an electron from the T1 to T2/T3 coppers, where the oxidative half-reaction proceeds by reducing oxygen into water. Since the primary electron acceptor of McoP is oxygen, the DET reaction with the electrode scarcely proceeds, even under the application of a sufficient oxidation potential of the T1 copper. This redox mechanism of McoP inspired us to construct an engineered enzyme that facilitates the DET reaction with the electrode without losing electrons to the oxidative half-reaction with oxygen. By introducing mutations to the T2/T3 copper ligands, His396, and His 459, we created an enzyme that no longer reduces oxygen via the T2/T3 copper. Instead, it retains the active catalytic site for the reductive half-reaction, T1 copper, thereby producing an engineered enzyme, termed “copper dehydrogenase,” which utilizes the electrode as the primary electron acceptor under the application of the oxidation potential for T1 copper (Fig. 1b).

a F290I multicopper oxidase protein from Pyrobaculum aerophilum (McoP) and (b) McoP F290I/H396A/H459A (CoDH). Both (a, b) catalyze the reductive half-reaction to oxidize levodopa with T1 copper (orange). F290I McoP can then transfer electrons from T1 to T2/T3 coppers (orange), where the oxidative half-reaction proceeds by reducing oxygen (red) to water. However, the direct electron transfer (DET) reaction with the electrode is negligible. In contrast, CoDH does not possess an active T2/T3 copper catalytic site and therefore cannot utilize oxygen as an electron acceptor. Consequently, the DET reaction with the electrode dominates when the oxidation potential is applied to the electrode.

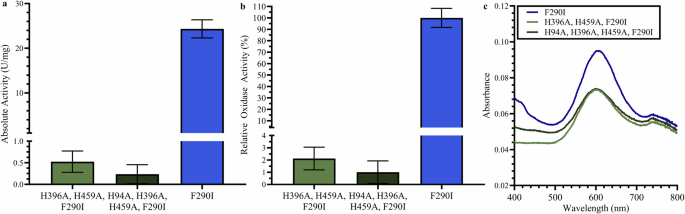

Figure 2 shows the characterization of the created mutant McoPs, which have mutations introduced into the T2/T3 copper ligands. Recombinant McoPs were purified through a process of heat treatment at 80 °C for 10 min, followed by purification using Q-Sepharose column chromatography (Supplementary Fig. 2). The purified mutants, F290I- H396A/H459A and F290I- H94A/ H396A/H459A, exhibited a marked decrease (less than 1.5% of F290I McoP) in oxidase activity using ABTS as the substrate and oxygen as the electron acceptor. Figure 2a shows the absolute activity measured as U/mg, while Fig. 2b displays the relative oxidase activity for each mutant compared to the F290I mutant, all using triplicate experiments. To confirm the presence of the Cu atom at the T1 binding center in the mutant McoPs, the visible absorption spectra of F290I McoP, F290I-H396A/H459A McoP and F290I-H94A/ H396A/H459A McoP were measured. T1 copper shows a strong absorption band around 600 nm31, whereas T2/T3 coppers do not display any absorption spectra. The absorption around 600 nm is attributed to the T1 copper ligand, specifically the Cys residue, which shows SCys → CuII charge-transfer excitation and gives the enzyme its intense blue color. In contrast, T2/T3 copper ligands do not contain Cys residues. These results support that all mutant enzymes harbor T1 copper (Fig. 2c). The decrease in absorption spectra at 600 nm for the T2/T3 copper ligand mutants, F290I-H396A/H459A and F290I-H94A/H396A/H459A, compared to McoP F290I, is hypothesized to result from a local structural change around the T1 copper binding site, as these mutations sites are in close proximity to the T1 copper binding site. This, paired with the drastic loss in oxidase activity, suggests that only the T1 copper center remains in mutants F290I- H396A/H459A and F290I- H94A/ H396A/H459A. This indicates that the mutant McoPs retain the Cu atom at the T1 Cu binding site32.

a Absolute (n = 3) and (b) relative oxidase activity (n = 3) of F290I- H396A/H459A, F290I-H94A/H396A/H459A, and F290I mutants. c Absorption spectra of a single representative sample of McoP F290I and CoDH mutants. Here, the blue line denotes F290I mutant, the green line denotes F290I- H396A/H459A, and the dark green line denotes F290I-H94A/H396A/H459A. Error bars represent standard deviation for n = 3 measurements.

Since there have not been any reported synthetic electron acceptors for McoP, the dehydrogenase activities of these mutant McoPs were investigated via chronoamperometry without employing any synthetic mediators, but under direct oxidation of the enzyme and subsequent transfer of electrons directly to the electrode surface. In this study, enzymes were covalently immobilized on the gold electrode with a SAM using dithiobis succinimmidyl hexanoate (DSH). Figure 3 shows the chronoamperometric investigations of DSH immobilized F2901-H396A/H459A McoP mutant or a DSH immobilized F290I McoP gold disk electrodes (Φ = 2 mm) as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl junction reference electrode, and a Pt counter electrode, across a levodopa concentration range of 0–360 µM in both an oxygenated and deoxygenated 100 mM PPB (pH 7.0) solution. While both electrode groups showed a levodopa-dependent concentration current increase under deoxygenated conditions, the F290I McoP significantly lost its catalytic current when investigated under atmospheric conditions in the presence of oxygen. The slope decreased from 0.0025 μM/μA (deoxygenated) to 0.0003 μM/μA (atmospheric), and the peak chronoamperometric signal showed a loss of 88% at a tested 360 µM levodopa concentration. In contrast, the F2901-H396A/H459A McoP mutant maintained its catalytic current even under atmospheric conditions compared to deoxygenated conditions; the slope decreased from 0.0025 μM/μA (deoxygenated) to 0.0021 μM/μA (atmospheric), and the peak chronoamperometric signal showed a loss of 21% at the tested 360 µM levodopa concentration. These results demonstrated that the F2901-H396A/H459A mutations significantly repressed oxidase activity and enhanced dehydrogenase activity through DET with the electrode surface when compared to F290I McoP. Therefore, we designated the McoP mutant with mutations in T2/T3 copper ligands, which exclusively exhibits DET-type dehydrogenase activity, as copper dehydrogenases (CoDHs).

Here, O2 denotes oxygen. The orange line represents CoDH with oxygen, and the red line represents CoDH without oxygen. The purple line represents McoP with oxygen, and the blue line represents McoP without oxygen. Error bars represent standard deviation for n = 3 measurements.

After confirming the reduction of oxidase activity in McoP, the levodopa sensor performance was assessed in 100 mM PPB (pH 7.0) using a DSH-CoDH GDE (n = 3, Φ = 2 mm) working electrode, an Ag/AgCl junction reference electrode, and a Pt counter electrode. CoDH was immobilized on the gold microwire using DSH, which was advantageous for two primary reasons. First, by covalently binding the enzyme closely to the electrode surface, efficient DET can be obtained as the rate of electron transfer corresponds to distance33,34. Second, the self-assembled monolayer helped mitigate nonspecific noise from the direct oxidation of levodopa on the gold electrode (Supplementary Fig. 3), reducing the background levodopa sensitivity by ~600%. For chronoamperometric measurements, a 0.3 V overpotential was applied for 180 s, with Fig. 4a showing the chronoamperometric calibration curve with an R2 value of 1.00 and a limit of detection (LOD) of 0.72 µM which was found by taking 3 times the standard deviation of the current measured at the lowest detectable levodopa concentration (0.1 µM), divided by the sensitivity of the sensor. All LODs in this study were calculated using this method.

a Chronoamperometric calibration curve in 100 mM PPB where light blue corresponds to cerebral spinal fluid therapeutic window, and red corresponds to the plasma therapeutic window. b Sensor storage stability evaluated over 21 days (days 1, 7, and 21). c Impact of modulating 50–150 mM KCl. d Impact of changing the pH of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer between 6, 7, and 8. e Impact of temperature between room temperature (25 °C) and body temperature (37 °C). For (a–e) error bars represent standard deviation for n = 3 measurements.

Storage stability of levodopa sensor

Being able to store the sensor for an extended period is essential to translate the sensor from benchtop to practical use. Using GDEs (n = 3, Φ = 2 mm) immobilized with CoDH via DSH as previously described, we investigated the 21-day storage stability with the sensors stored at 4 °C in 100 mM PPB when not in use. Figure 4b shows the 21-day storage stability of the sensor, depicting levodopa calibration curves on days 1, 7, and 21 in 100 mM PPB. The calculated sensitivity remained nearly constant, staying within 5% of the day 1 value across the entire 21-day period. Standard deviation was calculated from triplicate experiments. The sensors displayed reproducible measurements across the first 7 consecutive days of repeated use, with Supplementary Fig. 4 showing the calibration curves for levodopa measurements in 100 mM PPB (pH 7.0) over these days.

Impact of environmental changes on the levodopa sensor

Successful future implantation of a levodopa sensor will require that the sensor signal remain stable in various ion concentrations and pH, as well as at body temperature. Using the same three-electrode setup as mentioned above, Fig. 4c shows minimal chronoamperometric signal change from a baseline of 10 µM levodopa as the total concentration of KCl increases. pH modulation (Fig. 4d) follows a similar trend with no drastic signal changes between pH 6 and 8, which represents a range far exceeding typical transient pH changes in vivo. Finally, Fig. 4e highlights how there is minimal chronoamperometric signal increase across 1–55 µM levodopa at room temperature (25 °C) compared to body temperature (37 °C), which can be attributed to the increased buffer solution temperature increasing the electron transfer rate between the enzyme and electrode surface.

Specificity towards levodopa

The specificity of the levodopa sensor was investigated for endogenous and exogenous ingredients/interferents, demonstrating CoDH’s high selectivity for levodopa. Chronoamperometric signal bias was calculated by measuring the signal change from a 10 µM background levodopa solution. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows that a 0.3 V chronoamperometric pulse minimized the signal bias from electroactive substrates such as acetaminophen, which are readily oxidized at higher potentials. Furthermore, at an applied potential of 0.3 V, there was minimal signal bias (compared to 0.4 V and 0.5 V) from interferents like methyldopa and carbidopa, which exist along the levodopa metabolic pathway or are prescribed as adjunct medications.

Figure 5 shows how the addition of endogenous and exogenous interferents impacts the measured electrochemical signal. Interferents were selected considering their structural resemblance to levodopa, role in the levodopa metabolic pathway, co-administration with levodopa in PD treatment, or common usage as test substrates for continuous glucose monitoring systems35,36. The studied interferents include levodopa metabolites—methyldopa, dopamine, chlorthalidone, amantadine, homovanillic acid, epinephrine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl ethanol, norepinephrine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid—adjunct medications such as carbidopa, and common interferents found in interstitial fluid, including lactose, galactose, fructose, maltose, glucose, acetaminophen, lactate, and urea. The structure and a brief description of each interferent, which may undergo nonspecific interactions with the enzyme, is shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. Figure 5 shows that the chronoamperometric response is minimally impacted by the addition of interferents, with only methyldopa causing a bias slightly greater than 10%. It is important to note that both the tested and physiological methyldopa concentrations exist at several times higher levels than levodopa in vivo.

The legend can be read vertically to correspond with the columns in the chart. Error bars represent standard deviation for n = 3 measurements.

Miniaturized levodopa sensor

Microwire electrodes (n = 9, Φ = 76.2 µm) were used as the working and reference/counter electrodes in a 2-electrode electrochemical scheme, as outlined in the experimental section. The employed protocol increased the electrode surface area, allowing for a higher density of immobilized enzyme37,38. Like the GDEs, CoDH was immobilized on the microwires via DSH-SAM. However, the microwire sensor employed a two-electrode setup instead of a three-electrode setup, with a gold microwire as the working electrode and a shared silver/silver chloride wire serving as both reference and counter electrode. Figure 6 shows the chronoamperometric measurements in 100 mM PPB (pH 7.0). the Pearson Coefficient was 0.99 across the therapeutic range (0–55 µM) with a LOD of 138 nM and a sensitivity of 0.0042 µA/µM, indicating that the levodopa sensor is well-positioned for future in vivo experimentation.

a Raw data showing the first ~170 s of chronoamperograms. b Calibration curve of the microwire sensors in 100 mM PPB, with calculated LOD and sensitivity. The light blue portion corresponds to cerebral spinal fluid therapeutic window and red portion corresponds to the plasma therapeutic window. Error bars represent standard deviation for n = 9 measurements.

Discussion

This work presents the development of a novel DET-type engineered enzyme for continuous levodopa monitoring using chronoamperometry. The proposed levodopa sensor could improve dosing titrations for patients with PD, particularly when used in conjunction with continuous enteral or subcutaneous levodopa administration39.

Considering the limited number of DET-type enzymes, many challenges have been reported in creating DET-type enzymes from cofactor-binding dehydrogenases. These methods include fusing electron transfer subunits40 or modifying the enzyme surface with redox mediators to construct ‘quasi-DET-type’ enzymes41. However, these methods are not applicable when the starting oxidoreductases are oxidases, which utilize oxygen as the primary electron acceptor. There have been attempts to create ‘dehydrogenases’ from ‘oxidases’ by mutating the residues responsible for the oxidative half-reaction that utilizes oxygen as the electron acceptor. The strategies can be categorized as: (1) mutating the putative oxygen binding site, (2) investigating the vicinities where the reaction with oxygen may take place, including mutating the residues responsible for the proton relay system, and (3) mutating the residues structuring the possible oxygen access routes to the isoalloxazine ring42. These challenges have primarily focused on flavin-dependent oxidoreductases, such as flavin mononucleotide harboring lactate oxidase43,44,45, flavin adenine dinucleotide harboring oxidases like glucose oxidase46,47, cholesterol oxidase48, fructosyl amino acid/peptide oxidases49,50,51, D-amino acid oxidase52, and glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase53. Regarding MCOs, it has been reported that applying sodium azide to laccase, where azide ions bind to the T2/T3 copper cluster and inhibit oxygen reduction by the enzyme, thereby repressing oxidase activity in the anodic reaction and enabling laccase to exhibit DET with the electrode, forming a DET-type enzyme fuel cell47,51,54. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no attempts to engineer multicopper oxidases into dehydrogenases, nor investigations into the impact of mutations in T2/T3 copper ligand residues on the oxidative half-reaction. The current study clearly demonstrated that mutations in T2/T3 copper ligand residues resulted in minimal impact in the enzyme’s reductive half-reaction but almost eliminated the use of oxygen as an electron acceptor. Therefore, this engineering strategy could be generally applicable for constructing DET-type dehydrogenases from multicopper oxidases, which have been reported to possess a variety of substrate specificities.

Several attributes of the sensor were investigated, such as storage stability and applied overpotential. A key distinction from other levodopa enzymatic sensors is that we used an enzyme derived from the hyperthermophilic archaeon P. aerophilum. This enzyme has demonstrated a half-life of approximately 6 h even at temperatures as high as 353 K (80 °C)28. In addition to this inherent extreme thermal stability, bioelectrochemical devices using this enzyme have demonstrated its long-term continuous operation. Specifically, McoP was used to construct an enzymatic fuel cell system, which retained 70% of its initial activity over 14 days of continuous operation at room temperature55. These findings support the long-term stability of CoDH and its suitability for continuous monitoring applications in vivo.

A thorough interference evaluation was also conducted, looking at both nonspecific substrates of the enzyme and common electroactive substrates found in interstitial fluid and plasma. As introduced above, the development of levodopa sensors has faced significant challenges, particularly concerning enzyme specificity and sensitivity. Current approaches to measure levodopa rely on direct oxidation or levodopa oxidation by tyrosinase (Table 1), both of which present significant drawbacks56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65. Tyrosinase-based sensors suffer from broad substrate specificity, necessitating additional steps and materials to mitigate the impact of interferents. This is seen with non-specific reactions causing over 10% signal bias while testing only a few of the total number of possible endogenous and exogenous compounds (Supplementary Fig. 1). Current sensor configurations, including those described in the abovementioned studies, do not test key interferents (Supplementary Fig. 5) such as 3-O-methyldopa (a levodopa metabolite), amantadine (a commonly prescribed adjunct medication), and homovanillic acid (another levodopa metabolite), among others, which share many structural similarities to levodopa and can be present at concentrations several times higher than those of levodopa in vivo. Additionally, tyrosinase is sensitive to oxygen, posing further challenges to sensor accuracy and reliability in vivo where oxygen levels can fluctuate, as seen in current continuous glucose monitors today. In contrast, direct oxidation methods that use metal-organic frameworks or modified carbon sensors suffer from a lack of substrate specificity leading to inaccurate measurements in complex samples. This problem stems from most direct oxidation approaches relying on the oxidation of the 3, 4-hydroxy group on the phenyl of levodopa. This approach is highly nonspecific, as many common interfering phenolic compounds share hydroxy groups around a similar position, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6. Strategies have developed to mitigate background noise due to nonspecific reactions, including an additional ‘background’ electrode which will measure electroactive interfering signals. While this approach shows promise, these sensors remain inherently constrained by tyrosinase’s broad substrate specificity (cross-reacting with several substances, including levodopa, methyldopa, dopamine, carbidopa, amantadine, chlorthalidone), thus limiting their practical application. Additionally, this method, which measures a relative value (Δlevodopa) against the background, both complicates the calibrations and may hinder quantification of absolute levodopa values65.

In comparison to tyrosinase and direct levodopa oxidation, CoDH exhibits high stability and specificity towards levodopa and is capable of DET between the first T1 copper and the electrode surface. As highlighted in Table 1, our levodopa recognition element, CoDH, underwent rigorous interferent testing including many levodopa metabolites, adjunct medications, and common molecules in plasma and interstitial fluid. Among all tested interferents, only methyldopa exhibited a signal bias ranging from 5 to 10%. Methyldopa is a levodopa metabolite that can exist at higher concentrations in the plasma of PD patients due to its longer half-life compared to levodopa. Clinically, methyldopa tends to be present 1.5 to 3 times the concentration of levodopa in vivo, while in this evaluation, it was dosed at nearly 5 times the concentration, representing a significantly larger difference than expected clinically. At a clinical ratio (1.5 to 3 times), we would anticipate much lower signal bias with minimal clinical impact on the biosensor. An additional source of chronoamperometric signal bias is carbidopa, though it remains under 10%. Similar to methyldopa, carbidopa was evaluated at a 1:1 ratio, which is a significantly higher ratio to levodopa than is expected in vivo, where carbidopa is co-administered with levodopa at a ratio of either 1:4 or 1:10 (carbidopa: levodopa). Consequently, the expected signal bias from carbidopa in vivo will likely be much lower than what is shown in Fig. 5. CoDH’s improved specificity makes it an ideal candidate for integration into a continuous levodopa sensor for in vivo application. Sensor reversibility was also investigated by measuring chronoamperometric response in alternating solutions of 0 and 110 µM levodopa. Supplementary Figure S7 shows the response for triplicate sensor builds; tested over 6 full cycles. The results indicate that both the baseline and peak currents are consistently recovered across each cycle in 5 min of changing the concentration from 0–110 µM levodopa demonstrating that the kinetics of CoDH are sufficient for measuring rapid, and large changes in levodopa.

Additionally, as a DET-type enzyme, CoDH offers advantages due to its ability to bypass oxygen, interact with the electrode directly, helping mitigate the impact of electroactive interfering compounds which can oxidize at the electrode under high potentials. The proposed levodopa sensor was successfully miniaturized into a form factor suitable for subcutaneous insertion and future in vivo experimentation. Comparing the GDE with the microwire levodopa sensors, the microwire sensor demonstrated a lower LOD and increased sensitivity towards levodopa, which is crucial given the therapeutically relevant low micromolar concentrations of levodopa. However, the sensor’s sensitivity is insufficient for detecting levodopa concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (150 − 250 ng/mL, or 0.76 − 1.26 μM)6. While this limitation exists, the proposed levodopa sensor is designed specifically for measuring levodopa in interstitial fluid, which is more accessible and preferable for sensor insertion and measurement.

In conclusion, our work details the development and characterization of a novel, engineered enzyme, CoDH, demonstrating high specificity for levodopa. This engineered enzyme was then fabricated into a chronoamperometric levodopa sensor. By introducing mutations into the type 2 and type 3 copper ligand histidine residues of McoP, the enzyme drastically decreased its oxidase activity while enhancing DET activity with the electrode surface. Using this engineered CoDH, chronoamperometric based levodopa sensors were constructed. The initial GDE based levodopa sensor was translated into a gold microwire form factor which is suitable for subcutaneous insertion and was evaluated across the therapeutic range of levodopa. The sensors specificity was thoroughly investigated using both endogenous and exogenous interfering compounds, including those involved in the levodopa metabolic pathway, adjunct medications, and other common molecules found in vivo. While this work lays the foundation for developing a fully continuous levodopa sensor system that could be integrated with levodopa infusion systems, several challenges remain. These include investigating the biocompatibility of the continuous sensor and understanding its stability in vivo. Future work will include developing and testing the impact of adding outer membranes or biocompatibility layers to sensor sensitivity and stability. Additionally, more complex algorithms will be needed to account for various types of in vivo noise such as movement artifacts, fluctuations of the local environments, and time lags between the plasma and ISF compartment. There is tremendous clinical value in a continuous levodopa monitor, especially with the recent FDA approval of the first continuous levodopa infusion pump for late-stage PD patients66,67. The concept of a closed-loop levodopa infusion has garnered significant interest and could greatly enhance control and patient outcomes for many PD patients.

Methods

Reagents and materials

In this study, several enzymes (CoDH from Pyrobaculum aerophilum, Multicopper Oxidase from Pyrobaculum aerophilum (McoP), and Tyrosinase from mushroom) were used. CoDH, a novel engineered enzyme, was recombinantly produced using the expression vector pET-11a-pae1888 and purified as previously described28,29. McoP was also recombinantly produced using the expression vector pET-11a-pae1888 and purified as previously described. The vectors were transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL and cultivated as previously described. Tyrosinase from mushroom was purchased from Millipore Sigma (MA, USA). Dithiobis succinimmidyl hexanoate (DSH) was purchased from Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc. (Kumamoto, Japan). GDEs, platinum wire, and silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) reference electrodes were purchased from BAS Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Perfluoroalkoxy alkane (PFA)-Coated Gold Wire and PFA-Coated Silver Wire were purchased from A-M systems (Sequim, WA, USA). 2,2’-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS), acetone, levodopa (3,4-Dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine), carbidopa (S)-3-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-2-hydrazino-2-methylpropionic acid monohydrate, 3-O-methyldopa, homovanillic acid, epinephrine, dopamine hydrochloride, chlorthalidone, amantadine hydrochloride, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, 3-hydroxytyrosol, ( − )-norepinephrine, creatine, lactose monohydrate, D-(+)-galactose, D-(−)-fructose, D-maltose monohydrate, D-(+)-glucose, L(+)-ascorbic acid, acetaminophen, sodium L-lactate, and urea were purchased from Millipore Sigma (MA, USA). All electrochemical measurements were performed on the VSP-3e Potentiostat from BioLogic (Pariset, France).

Construction of mutant McoP, CoDH

Amino acid mutations in the pae1888-f290i29 (gene were created using the PrimeSTAR Mutagenesis Basal Kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. pET1888-f290i plasmid containing pae1888-f290i was used as a template, using suitable primers (Supplementary Table S1). The successful introduction of the mutation in the resulting plasmid was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Determination of enzyme activity, protein concentration and spectroscopic observation

The MCO activity was measured as described previously using a Shimadzu UV-1280 instrument equipped with a thermostat29. The MCO reaction mixture contained 100 mM Britton-Robinson buffer, 1 mM ABTS, and the enzyme for a total volume of 1 mL. After incubating the reaction mixture without ABTS at 50 °C for 2 min in a cuvette with a 1.0-cm light path, the reaction was started by adding ABTS. The MCO activity was monitored by measuring the initial increase in absorbance at 420 nm. One enzyme unit was defined as the amount of enzyme catalyzing the oxidation of 1 μmol of ABTS per min at 50 °C. A millimolar absorption coefficient (ε mM) of 36 mM−1 cm−1 at 420 nm was used for ABTS. Protein concentration was determined using Pierce Coomassie (Bradford) Protein Assay Kit supplied by Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. To detect the T1 copper within the enzyme, 200 µL of a 1 mg/ml solution of McoP mutants in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.2) was added to each well of a 96-well microtiter plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Absorption spectra changes, with a light-path length of 4 mm, were recorded from 400 to 800 nm using a Multiskan GO microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Preparation of enzyme: recombinant expression and purification

Recombinant CoDH was prepared using the expression vector pET-11a-pae1888 plasmid, which contains the oxygen insensitive mutation as shown in the Supplementary Information. These vectors were transformed into E.coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL and cultivated according to our previous report28,29. Transformed E. coli was cultured at 37 °C in 1000 mL of LB medium containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin until the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.6. Recombinant protein expression was induced by adding 0.1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside, and the culture was continued at 20 °C for an additional 21 h. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation. Harvested wet cells were disrupted by ultrasonication in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.2. The lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min and copper sulfate was added to the supernatant to reach a final concentration of 1 mM. The solution was then incubated at 4 °C for 16 h. Following this, the enzyme solution was heated at 80 °C for 10 min and denatured proteins were removed by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 10 min). The supernatant was then dialyzed overnight against 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.2. The dialyzed sample was applied to a Q-Sepharose Fast Flow column (Cytiva) equilibrated with 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.2), after which the column was washed with the same buffer. The enzyme was then eluted with a linear gradient of 0–500 mM NaCl in the same buffer. Active fractions were pooled, and the enzyme solution was exchanged for 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) using ultrafiltration (Vivaspin Turbo 15, with a 30,000 molecular weight cut-off; Sartorius, Germany). Purity of the purified protein as confirmed by SDS-PAGE shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Preparation of GDE levodopa sensors

GDEs (Φ = 2 mm) were polished using 0.3 and 0.05 µm alumina powder, then washed with piranha (H2SO4:30% H2O2 = 3:1) for 1 h. These electrodes were subsequently electrochemically cleaned using cyclic voltammetry sweeps (0.0 V–1.2 V) in a 50 mM KOH solution. The electrodes were then washed in acetone and incubated overnight ( ~ 16 h) in a 100 µM DSH-SAM solution at 25 °C and 300 rpm. Following this, the electrodes were immersed in a 0.014 mg/ml enzyme solution and incubated overnight in the same conditions. Afterwards, the electrodes were rinsed with 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (PPB, pH 7.0) and stored in the same buffer until use. Electrical impedance spectroscopy was employed to confirm enzyme immobilization, measuring the increase in impedance relative to both the bare electrode and electrode with DSH only (Supplementary Fig. 8). The immobilized DSH concentration and applied overpotential for measurement were optimized as detailed in Supplementary Fig. 9 and Table S2.

Preparation of gold microwire levodopa sensors

Gold wire (Φ = 76.2 µm) had some of its protective PFA insulation removed with a blade and then cleaned using cyclic voltammetry sweeps between −0.2 V and −1.2 V (1 V/s) in 100 mM NaOH. The exposed gold was roughened by pulsing 10,000 times between 0 and 2 V in 500 mM H2SO4 for 20 ms each pulse, having no wait time between cycles. The functional surface area of the gold wire electrodes was calculated by conducting cyclic voltammetry sweeps between 0 V and 1.5 V in 50 mM H2SO4 at a scan rate of 50 mV/s and integrating the area under the 0.9 V reduction peak. Subsequently, the gold wires were incubated in a 100 µM DSH-SAM solution at room temperature. Following this, they were immersed in a 0.014 mg/ml enzyme solution (either CoDH or McoP) for 18 h and then stored in 100 mM PPB (pH 7.0) until use. Silver wire (Φ= 177 µm) also had PFA insulation removed with a blade. Afterwards, it was soaked overnight in bleach solution and then stored in 1 M KCl until use.

Electrochemical levodopa measurement

All constructed working electrodes were evaluated using a 20 ml water-jacket cell, with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode (double junction or wire) and a platinum counter electrode, with the exception that gold microwire electrodes use a 2-electrode scheme, shorting the counter and reference. Chronoamperometric (bias potential of +300 mV vs Ag/AgCl) were conducted with the enzyme modified working electrodes. During the measurement process, readings were continuously sampled to construct calibration curves. The chronoamperometric signal was observed for the initial three minutes with readings sampled at 0.1-second intervals. Volumes of a stock levodopa solution were sequentially added to the electrochemical cell to achieve the desired test concentrations. Unless stated otherwise, all levodopa calibration curves were conducted across a 0–55 µM levodopa concentration range. To determine the ideal applied potential for electrochemical measurement, we conducted an optimization study modulating the applied potential as detailed in Supplementary Fig. 10. The results of our electrochemical studies were validated using positive (0–20 mM levodopa) and negative controls (0–360 µM levodopa), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Levodopa sensor reversibility evaluation

One electrochemical cell contained 10 mL of 110 µM levodopa solution, while another electrochemical cell contained 10 mL of 100 mM PPB (pH 7.0). Initially, the GDE-CoDH electrodes (n = 3) were placed in 100 mM PPB for 6 min with a 0.3 V overpotential applied, then transferred to the 110 µM levodopa solution for another 6 min, maintaining the same 0.3 V overpotential. This 12 min sequence constituted one cycle, with the electrode group undergoing six cycles in total. The final 30 s of chronoamperometric signal for both the 100 mM PPB (pH 7.0) and the 110 µM levodopa solution is shown in Supplementary Fig. 7.

Investigation of the effect of interfering substances on the sensor signal

The constructed enzyme electrodes were evaluated in a 20 ml water jacket cell. All electrochemical measurements were conducted in the presence of 10 µM levodopa and a variety of interferents. These interferents encompassed co-administered drugs such as 10 µM carbidopa, as well as a range of dopamine analogues, including 48 µM 3-O-methyldopa, 450 nM homovanillic acid, 327 pM epinephrine, 653 pM dopamine, 29.5 µM chlorthalidone, 29 µM amantadine, 10.7 nM 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, 3.7 nM norepinephrine, and 11.9 nM 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol. A summary of these physiological interferents including their molecular structure and rationale for their inclusion in this interference study is summarized in Supplementary Fig. 6. Electroactive interferents were also examined, such as 200 µM acetaminophen and 114 µM ascorbic acid, other interfering substrates investigated included 333 µM galactose, 3.5 mM maltose, 10 mM glucose, 2.5 mM lactate, and 14.5 mM urea. The study also evaluated the impacts of environmental factors by measuring the electrochemical signal response across pH 5–8 and temperatures from 36 °C to 38 °C, and with changing ion concentrations, from 50 to 150 mM potassium chloride, 5 mM potassium, and 150 mM sodium. A subsidiary interference study was undertaken using key physiological interferents. In this study, we used Tyrosinase from mushrooms as a comparison to our enzyme, with results summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Responses