The effect of antibacterial peptide ε-Polylysine against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm in marine environment

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) is a gram-negative bacteria with high environmental adaptability and fast growth and reproduction1. P. aeruginosa can thrive in a variety of aquatic and terrestrial environments, including lakes, rivers, soils2. P. aeruginosa is also a conditional pathogen, causing wound infection by attaching to medical equipment3. Bacteria generally have two life stages: unicellular (planktonic) and multicellular (aggregation into colonies that facilitate attachment to surfaces). Under suitable growth conditions, aggregated bacterial communities can form biofilms4.

Biofilms comprising microorganisms attach to solid surfaces and wrap themselves in the extracellular matrix to form a thin film5. Microorganisms can secrete extracellular polymers (EPS), such as proteins, polysaccharides and nucleic acids6,7,8. EPS keep microbes embedded in the extracellular matrix, providing important nutrients and resistance to possible stressors9. Thus, biofilms exist in a stable and durable state that can be difficult to eradicate3. Bacteria within biofilm can also resist adverse external conditions, such as humidity and temperature, and various structures within biofilms can provide additional resistance to antibiotics2,10. In extreme cases, the bacteria within biofilm can tolerate up to 1000 times higher antibiotic concentrations than bacteria in suspension. Strategies aimed at inhibiting biofilms are assessed based on their ability to prevent, destroy or weakening the biofilm-associated microbial community. To date, several methods have been developed, including antibiotics, antimicrobial peptides, and catalytic antibacterial robots11,12,13. In clinical settings, biofilms can be difficult to treat with antibiotics alone, which lead to the development of chronic diseases and increasing morbidity and mortality2,14,15. In marine environments, the attachment of P. aeruginosa can powerfully shorten the service life of large-scale marine facilities. Thus, there is an urgent need to identify novel natural agents with antibacterial and anti-biofilm activity. The use of traditional antibiotics, which remain the most common antimicrobial method, can promote the development of antibiotic resistance. As environmental protection and safety awareness have increased, peptides with natural antibacterial functions have attracted more research attention. New strategies that disrupt or eradicate biofilm structure are being developed16,17.

ε-Polylysine (E-PL) is a polypeptide comprising 25–30 L-lysines residues connected by isopeptide bonds between ε-amino and α-carboxyl groups18,19. E-PL is a natural homologous polyamide with a molecular weight of 0.8–2.0 kDa. And it is safe, non-toxic, stable, ecofriendly19,20. E-PL is natural cationic antimicrobial peptides with broad-spectrum and high-intensity antibacterial properties21,22,23. Antimicrobial peptides can bind to the surface of bacterial membranes and alter their structure and permeability by inserting the hydrophobic end of the molecule into the lipid membrane24,25. To date, few studies have assessed the inhibitory effect of E-PL on P. aeruginosa biofilm26,27. These studies have primarily focused on E-PL composite materials that inhibited P. aeruginosa biofilm28,29,30,31. And few study explored that E-PL can inhibit the formation and morphology of biofilm in simply27. However, to date, none study has explored the bacterial motility and the mechanism of inhibited P. aeruginosa biofilm using bioinformatics. Herein, we investigated the inhibitory effect of E-PL on P. aeruginosa biofilm from the surface to internal microstructure, motility and metabolic of bacterial, and explored the inhibitory mechanism from the transcription level.

In this study, we used crystal violet staining to explore the inhibitory mechanism of E-PL on P. aeruginosa biofilm and used the CCK8 assay to assess the metabolic activity of bacteria within the biofilm. The biofilm structure was observed using scanning electron and fluorescence microscopy and the effect of E-PL on biofilm gene expression was investigated at the molecular level by fluorescence quantification and transcriptomics. The findings provide theoretical guidance for the future removal of P. aeruginosa biofilm in marine environments.

Results and Discussion

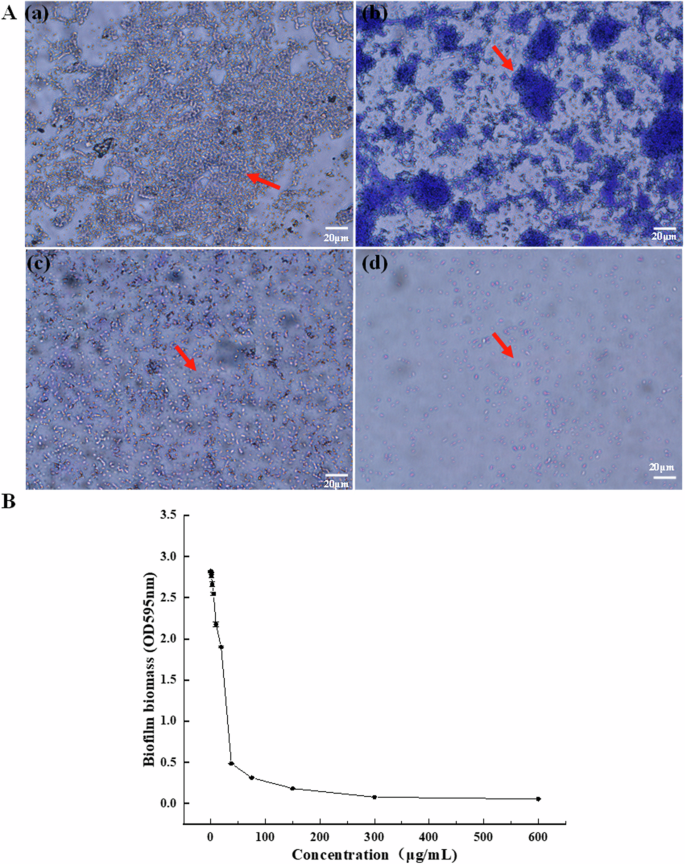

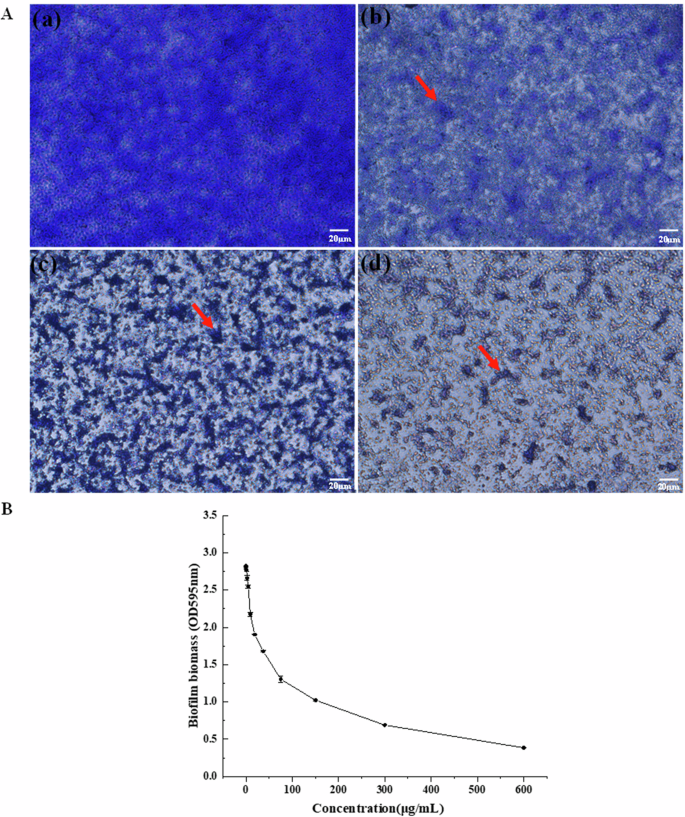

E-PL impairs biofilm formation

The current study assessed P. aeruginosa biofilm formation using crystal violet staining17. The number of bacteria increased gradually in the first 2 h and most were independent cells showing little evidence of adhesion and no obvious biofilm (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Mutual aggregation began after 4 h and biofilm biomass increased significantly at longer culture times, with a sharp rise at 10–12 h (Supplementary Fig. 1f, g). The biofilm also decreased with an increase in E-PL concentration. At 300 μg/mL, E-PL completely prevented the formation of P. aeruginosa biofilm (Fig. 1). These findings indicated that E-PL inhibits biofilm biomass formation in a concentration-dependent manner. E-PL was also found to destroy mature and fully-formed biofilm in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2). This finding indicated that E-PL inhibited the multicellular stage of P. aeruginosa.

A. The biofilm biomass was tested by crystal violet assay when the biofilms were treated with E-PL. (a) 0 μg/mL, (b) 150 μg/mL, (c) 300 μg/mL, (d) 600 μg/mL. Pixel of all photos size is 1360 × 1024, and the magnification was taken at 40 × with microscope. B. The biofilm biomass was tested by crystal violet assay at OD595nm. P. aeruginosa was cultured for 24 h in different E-PL concentrations of 0, 1.18, 2.35, 4.69, 9.38, 18.75, 37.5, 75, 150, 300, and 600 μg/mL, respectively.

A The biofilm biomass was tested by crystal violet assay when the biofilms were treated with E-PL. (a) 0 μg/mL, (b) 150 μg/mL, (c) 300 μg/mL, (d) 600 μg/mL. All photos were taken at 40 × microscope. Pixel of all photos size is 1360 × 1024, and the magnification was taken at 40 × with microscope. B The biofilm biomass was tested by crystal violet assay at OD595 nm. P. aeruginosa was cultured in different E-PL concentrations of 0, 1.18, 2.35, 4.69, 9.38, 18.75, 37.5, 75, 150, 300, and 600 μg/mL.

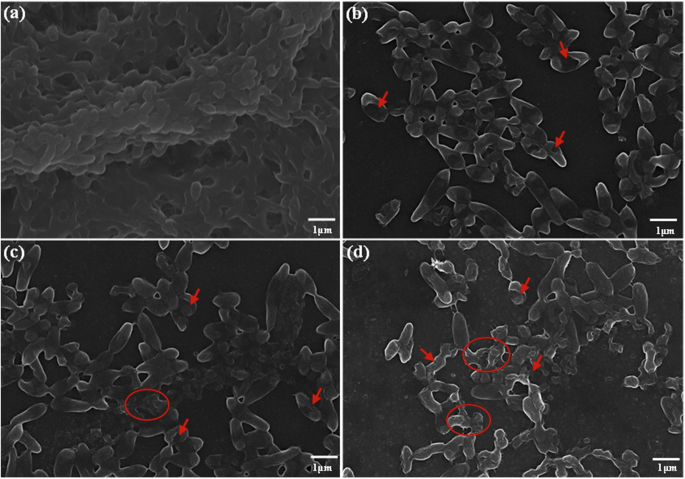

E-PL damages biofilm structure

To further investigate the effect of E-PL on P. aeruginosa biofilm, biofilm was pre-cultured with E-PL for 24 h (Fig. 3) and its structure and biomass were assessed by SEM. The untreated bacteria secreted more EPS, which tightly wrapped P. aeruginosa, and the aggregation density and thickness increased until a complete, dense, and multi-layered mature biofilm had formed (Fig. 3a). Bacteria in the biofilm were compact and the morphological surface was smooth, with no obvious depressions on the cell surface. In contrast, when P. aeruginosa was stimulated with E-PL, the biofilm surface was incompletely formed and EPS secretion was significantly reduced, limiting cell aggregation, and causing loosening and shedding of the biofilm surface. The number of bacteria was significantly lower, which led to biofilm rupture (Figs. 3b, c, and d). The morphology and structure of bacteria in the biofilm were deformed or broken, and the surface was depressed. In addition, under the stress of E-PL, the bacterial contents were released, and the cell surface became swollen or crumpled. These findings indicated that E-PL can effectively destroy the membrane structure of P. aeruginosa biofilms likely by disrupting its morphological structure and preventing bacteria from secreting EPS.

The biofilms with magnifications of 10.00k, a–d The biofilms were treated with E-PL 0 (a), (b) 150, (c) 300, (d) 600 μg/mL, respectively. Pixel of all photos size is 1360 × 1024, and the magnification was taken at 40× with microscope.

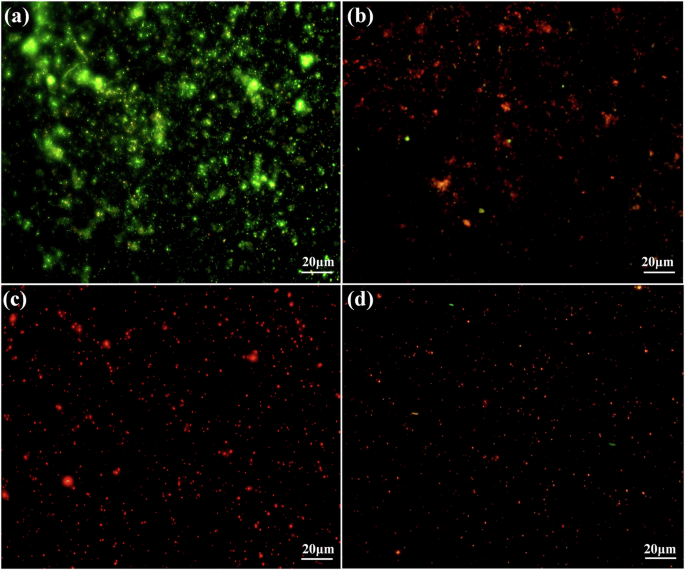

Additional effects of E-PL on biofilm structure

To assess the effect of E-PL on biofilm bacteria, the microbial population was labeled with SYTO9 and PI bicolor dyes. SYTO9 labels both intact and damaged cell membranes with green fluorescence. In contrast, PI only passes through damaged cell membranes. Upon entering the cell, PI causes the SYTO9 green fluorescence to decrease. When both dyes are present in bacteria, cells with an intact membrane structure fluoresce green, while those with a damaged membrane structure fluoresce red. While the bacteria treated with the 150, 300, and 600 μg/mL concentrations had independent and single red fluorescence, those in the control group had green or yellow-green fluorescence (Fig. 4). In the control group, obvious biofilm and bacteria in the membrane emitted green fluorescence (Fig. 4a). After treatment with E-PL, the bacteria no longer aggregate, no obvious biofilm was formed, and the number of cells was reduced. These findings indicate that E-PL can destroy bacteria in biofilm and inhibit bacterial metabolic activity and proliferation by destroying the bacterial cell membrane.

Fluorescence microscope images of biofilms when exposed to different E-PL concentrations of (a) 0, (b) 150, (c) 300, (d) 600 μg/mL. Pixel of all photos size is 1360 × 1024, and the magnification was taken at 40 × with microscope.

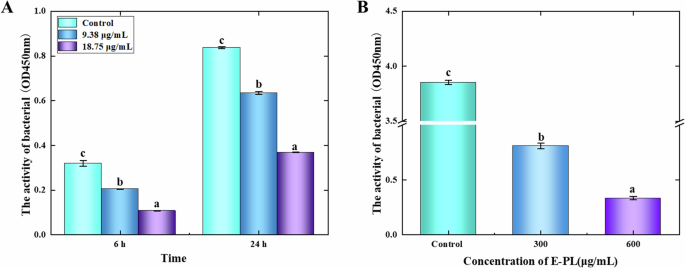

Metabolic activity of biofilm bacteria

The current findings confirmed that E-PL has an important destructive effect on biofilm, likely because biofilm is primarily composed of bacteria and EPS. To further explore the effects of E-PL on biofilm, the metabolic activity of biofilm bacteria was assessed. After 6 h of E-PL treatment, the OD values in the 18.75 and 9.38 μg/mL groups were significantly reduced from 0.32 to 0.205 (18.75 μg/mL) and 0.108 (9. 38 μg/mL), respectively, compared with the control group (OD = 0.32) (Fig. 5). After 24 h of treatment, the control group had an OD value of 0.84, while the experimental groups had values of 0. 63 and 0.4 with 9.38 and 18.75 μg/mL treatment, respectively (Fig. 5A). Similar results have been shown in response to other bacteriostatic substances, including quercetin and chitosan, which also reduce the number of biofilm bacteria17,32. These findings indicate that E-PL effectively inhibited the metabolic activity of bacteria during biofilm formation.

The metabolic activity of bacteriocin E-PL on P. aeruginosa in biofilm formation (A) and mature biofilm (B). Single-factor analysis of variance and Tukey’s test were used for statistical analyses. The error bars represent standard deviation (SD, n = 3) and significant difference was indicated by different letters (a, b, c). (p < 0.05).

The effects of E-PL on the metabolic activity of bacteria in mature biofilms were also assessed. After treatment with 300 and 600 μg/mL E-PL, the metabolic activity of biofilm bacteria was significantly decreased. While the OD value of the control was 3.853, the OD values of the 300 and 600 μg/mL groups were 0.81 and 0.334, respectively (Fig. 5B). Thus, E-PL can effectively inhibit the metabolic activity of bacteria in biofilm and reduce bacterial cell adhesion to the matrix. Other bacteriostatic agents, nisin and the antimicrobial peptide, SAAP-148, have shown a similar capacity to destroy mature biofilms by killing the associated bacteria33,34.

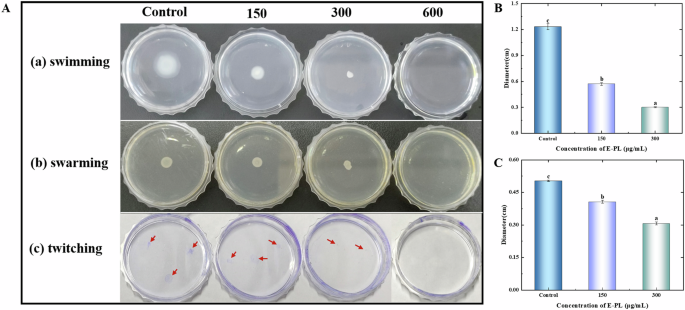

Motility of biofilm bacteria

Biofilm formation is often related to the movement of bacteria. Under complex conditions, the motility of bacteria is necessary for their survival and pathogenicity32,33. Flagellate-mediated motility and adhesion play an important role in microbial pathogenicity. Bacterial swimming and colony movement allow planktonic cells to attach to surfaces. As a result, the current study also assessed bacterial motility in E-PL-treated biofilms. Bacteria in the control group expanded from the inoculation point to the outer edge to form a large ring colony ring, indicating that P. aeruginosa was motile (Fig. 6). However, in the treatment groups, the size of the colony ring was dependent on E-PL concentration, and bacteria growth, reproduction, and motor diffusion were completely inhibited at 600 μg/mL. These findings indicated that E-PL successfully prevented bacterial adhesion and movement. Compared to the control group, 150 and 300 μg/mL E-PL also significantly inhibited P. aeruginosa locomotion and swarm movement while 600 μg/mL E-PL completely prevented swarm movement (Fig. 6). In addition, after staining, no obvious crystal violet attachment points were observed in the control group. Meanwhile, at 600 μg/mL E-PL, the plates were clean and smooth, and no trace of crystal violet was observed, indicating that E-PL effectively inhibited the puncture movement of bacteria in the medium. These findings indicate that E-PL can effectively inhibit the movement of bacteria in biofilm. Silver nitrate is reported to have a similar effect on biofilms35. This result more directly proves that E-PL can affect the movement of bacteria. These results are consistent with transcriptome analysis. Transcriptome analysis found that related to flagellar synthesis and chemotactic transduction genes (FlgE, wspE) mediated bacterial movement and were also significantly down-regulated.

The motilities of swimming (A), swarming (B), and twitching (C) of P. aeruginosa in the presence or absence of E-PL. The motilities of swimming (B), swarming (C), and twitching were determined by measuring the radius of bacterial colony. (P < 0.05, A–C).

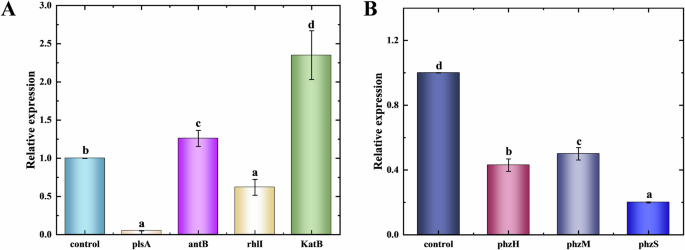

Gene expression of biofilm bacteria

To explore the effect of E-PL on biofilm bacterial gene expression, qPCR was used to detect pslA, rhlI, antB, katB, phzS, phzH, and phzM. E-PL treatment effectively downregulated plsA (0.05 folds), rhlI (0.62 folds), phzS (0.2 folds), phzH (0.43 folds), and phzM (0.5 folds) (Fig. 7). These results indicated that E-PL restricted the expression of genes involved in biofilm synthesis, thereby hindering biofilm formation. The relative expression of antB (1.26 folds) and katB (2.35 folds) was sharply up-regulated, indicating that E-PL has a regulatory effect on biofilm. Since extracellular polysaccharides are a major component of biofilms36, inhibition of the pslA gene is likely to prevent biofilm synthesis. As shown previously, the current study also revealed that genes involved in transcription regulation and phenazine synthesis affect biofilm synthesis35,37. The results were consistent with the transcription analysis. The founding showed that some key genes involved in QS pathway (rhlI/rhlR), Psl polysaccharide biosynthesis and alginate biosynthesis were significantly down-regulated after E-PL treatment. Psl, as a signal promoting the formation of P. aeruginosa biofilm, interacts with eDNA to form the main skeleton of bacterial biofilm38,39. This indicates that E-PL affects the synthesis of polysaccharides in the extracellular polymer during the synthesis of P. aeruginosa biofilm, thus hindering the formation of biofilm. Subsequent transcriptome analysis also found that AntB were up-regulate after E-PL treatment, catalase AntB proteins involved in o-aminobenzoic acid degradation.

A Genes related to biofilm and transcriptional regulation. B Phenozine compound-related genes. Single-factor analysis of variance and Tukey’s test were used for statistical analyses. The error bars represent standard deviation (SD, n = 3) and significant difference was indicated by different letters (a, b, c). (p < 0.05).

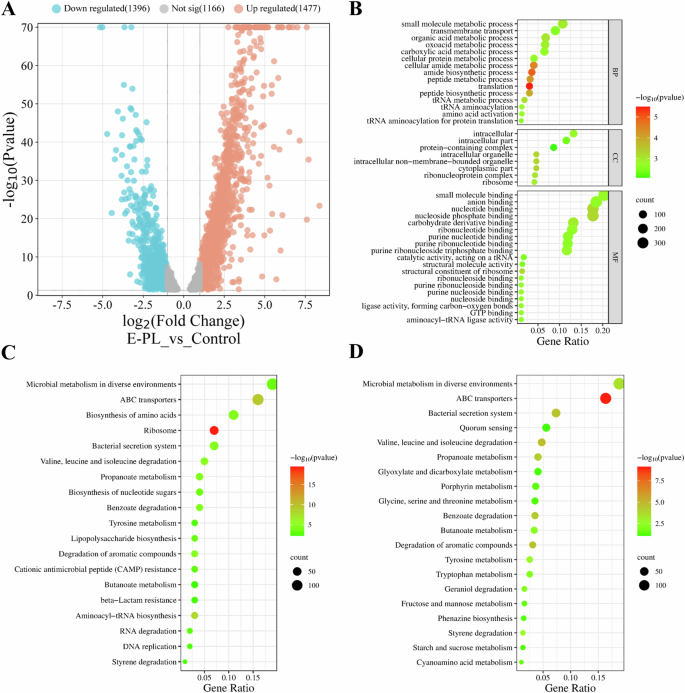

Transcriptome analysis

Transcriptomics is commonly used to analyze gene expression at the transcriptional level. Biofilm formation is a co-regulatory process coordinated by complex genetic networks. The current study used transcriptomics (RNA-Seq sequencing technology) to assess how E-PL impacted the bacterial gene expression profiles of mature P. aeruginosa biofilm. The results showed that differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were determined (Fig. 8A). The impact of E-PL on the gene expression profile of mature P. aeruginosa biofilm was further evaluated by identifying the GO and KEGG pathways of the DEGs (Fig. 8B). The GO map displayed that most of DEGs were functionally enriched in Biological Process (BP), Cellular Components (CC) and Molecular Function (MF). The BPs were concentrated in “small molecule metabolic processes”, “transmembrane transport,” and “organic acid metabolic processes.” Meanwhile, DEGs involved in Cellular Components (CC) were mainly concentrated in “intracellular,” “intracellular parts,” and “protein-containing complexes”, and MF was primarily concentrated in “small molecule binding,” “anion binding,” and “nucleotide binding”. The down-regulated DEGs were most enriched in membrane-related components, including “membrane composition,” “intrinsic components of the membrane,” and “overall composition of the membrane.” There was also a high number of genes involved in the “REDOX process” and “transport activity.” While “flavin adenine dinucleotide” activity was only slightly enriched, with a small number of involved genes, E-PL was shown to impact its activity on the transcriptional level.

A Volcano map of differentially expressed genes. B GO enrichment cluster analysis of the differential proteins. C KEGG pathway of the differential genes. D KEGG pathway of the down-regulated differential genes.

Analysis of the KEGG database was also used to identify genes that were enriched and differentially expressed in P. aeruginosa biofilm. DEGs were enriched in 20 KEGG pathways that were primarily involved in “microbial metabolism in different environments,” “ABC transport,” “amino acid biosynthesis,” and “ribosome and bacterial secretion” (Fig. 8C). Meanwhile, the downregulated genes were mainly involved in “ABC transport,” “degradation of valine, leucine, and isoleucine,” “quorum sensing,” “the bacterial secretion system for degrading aromatic compounds,” “the bacterial secretion system,” and “microbial metabolism in different environments” (Fig. 8D). “Phenazine synthesis” was also enriched in the KEGG pathway. These KEGG and GO displayed different functional gene changes, suggesting that E-PL may use several mechanisms to prevent biofilm formation.

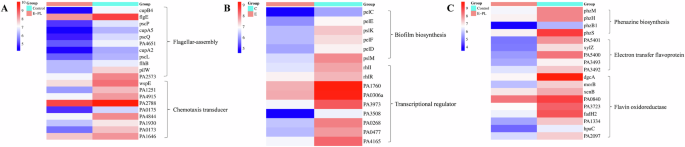

The bacterial flagellum is a locomotive organelle that allows many bacterial species to swim or aggregate on liquid and solid surfaces40,41. Bacteria typically rely on a complex sensory system to respond to environmental stimuli using the chemotactic signaling protein, to regulate the direction of flagellar movement42. Flagella are chemotactic, mediating the movement of bacteria toward favorable environments and away from unfavorable ones. Flagellate-mediated motility and adhesion correlate closely with the formation and drug resistance of bacterial biofilms. The results were consistent with the motility analysis showed that E-PL could inhibit the movement and diffusion of bacteria in the biofilm. In the E-PL-treated biofilms in the present study, flagella-related genes, including FlgE, cupA5, cupB4, pscL, and related genes, were downregulated (Fig. 9A). Thus, downregulating flagella-associated genes and chemotactic transduction reduces fimbriae and prevents bacteria from binding to surfaces or tissues, potentially inhibiting biofilm formation. Fimbriae formation is shown to correlate with P. aeruginosa virulence and downregulation of the felt protein, pilW, which is involved in felt formation and movement. The current study also showed the downregulated expression of genes involved in chemotactic transduction, including wspE, PA1251, PA4915, and PA2788, following E-PL treatment. In summary, E-PL induced the downregulation of flagellin, fibrinogen, and chemotaxis-related proteins on biofilm to prevent bacterial movement and adhesion, processes required for the bacterial life stage shift from the planktonic (mobile) to the biofilm (fixed) phase. These results are consistent with previous results on test of bacterial motility using three different ways (swimming, swarming and twitching). These results further demonstrated that E-PL affected the movement performance of bacteria at transcription level. These findings indicate that E-PL can effectively inhibit the movement of bacteria in biofilm.

A Changes of genes associated with the motility of P. aeruginosa receiving E-PL treatment. B Changes of genes associated with the adhesion of P. aeruginosa receiving E-PL treatment. C Changes of genes associated with the phenazine and electron transfer of P. aeruginosa receiving E-PL treatment. Red boxes represent increased proteins; gray boxes represent unchanged proteins.

Flagellate-mediated movement is necessary to initiate bacterial attachment to surfaces to form biofilms43. The transition from motility to biofilm formation may involve flagellar gene transcription is suppressed, and flagella are likely to be diluted to extinction by growth in the absence of neogenesis44. Cells are shown to adapt to the biofilm state by reducing metabolism, suggesting that metabolism-related genes may contribute to biofilm formation. Indeed, flagellar synthesis genes were inhibited in E-PL-treated biofilms, suggesting that these genes likely hinder flagellar growth and formation.

Transcriptomic analysis showed significant downregulation of genes involved in biofilm synthesis. Quorum sensing (QS), an intercellular communication system that effectively controls and regulates gene expression, directly impacts the release of virulence factors and biofilm synthesis during infection45. Three QS systems (las, rhl, and pqs) regulate P. aeruginosa virulence factor gene expression. The current study found that some key genes involved in the P. aeruginosa QS pathway, including rhlI/rhlR, PA1760, and PA0268 in the rhl system, were down-regulated in E-PL-treated biofilm (Fig. 9B). Genes involved in Psl polysaccharide biosynthesis and alginate biosynthesis, including pelC, pelE, pelK, pelF, pelD and pelM, were also downregulated. These findings indicated that E-PL affects the synthesis of polysaccharides in extracellular polymers, thus hindering P. aeruginosa biofilm formation. This result is consistent with previous results using qPCR (Fig. 7), which again proves that E-PL affects biofilm synthesis at transcription level.

Bacterial polysaccharides and eDNA coordinate to form the main structure of bacterial biofilm45 or serve as signals to promote biofilm formation46. Polysaccharide is the main component of the extracellular polymer matrix in mature biofilm. Psl acts as a signal to promote the formation of P. aeruginosa biofilm, and enhances the secretion of the extracellular polymer matrix. Pyocyanin is one of the secondary metabolites of P. aeruginosa, the synthesis of which is achieved through a complex cascade involving multiple genes, including phzABCDEFG and phzHMS47. This blue-green pigment causes oxidative stress in the host and disrupts host catalase and mitochondrial electron transfer. After E-PL treatment in this study, most of the key genes involved in phenazine biosynthesis, including phzM, phzH, phzB1, and phzS, were downregulated48. The inhibition of these genes resulted in decreased levels of PQS and pyocyanin. Genes related to flavin electron transfer, including PA3492, PA3493, PA2097, fadH2, and morB, which are involved in extracellular electron transfer, were also downregulated. These results further revealed that E-PL affected both P. aeruginosa biofilm synthesis and transcriptional regulation. The result was consistent with qPCR analysis, which proofed that E-PL regulated biofilm synthesis.

In summary, this study identified that E-PL may inhibit biofilm formation at the molecular level by preventing flagellar gene transcription during biofilm formation and thereby destroying flagellate-mediated bacterial movement and surface attachment. The release of P. aeruginosa virulence factors during infection and polysaccharides synthesized in the extracellular polymer during biofilm formation may also interact with eDNA to form the main skeleton of bacterial biofilms or promote biofilm formation. In addition, pyocyanin, one of the secondary metabolites of P. aeruginosa, causes oxidative stress in the host, disrupting host catalase and mitochondrial electron transport. These findings suggest that E-PL affects biofilm formation by influencing bacterial activity and metabolic gene expression.

In conclusion, this study explored the effect of E-PL on P. aeruginosa biofilm synthesis. E-PL was shown to inhibit and destroy the formation of biofilm in a concentration-dependent manner by (1) inhibiting the secretion of extracellular polymer to damage the biofilm structure, (2) reducing the metabolic activity of the biofilm bacteria, (3) limiting bacterial motility, and (4) regulating the expression of genes involved in synthesizing flagella, chemotactic transduction, extracellular polymeric polysaccharide synthesis, lifetime metabolism, and electron transfer. These findings suggest that the natural and environmentally friendly antimicrobial peptide, E-PL, has great potential for use in biofilm treatment in many industries.

Methods

Bacterial and reagents

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (MCCC1A10045) was obtained from the Marine Culture Collection of China (Xiamen, China). Crystal violet (0.1%) was purchased from Solarbio Life Services (Beijing, China). Glutaraldehyde Fixation Solution (2.5%) was purchased from Absin Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Crystal violet tested biofilm formation

Crystal violet staining was used to assess biofilm formation as described previously17. 100 μL of the strain was taken into a centrifuge tube containing 10 mL of fresh medium and placed in a constant temperature incubator at 150 rpm at 30 °C for about 24 h until it reached sharply growth stage. The medium in which bacteria are placed in microplates with LB medium. The high concentration of E-PL is dissolved in aqueous solution and then diluted in medium when used. The P. aeruginosa concentration was 1 × 106 CFU/mL in 96-well plates with different concentrations of E-PL (0, 1.18, 2.35, 4.69, 9.38, 18.75, 37.5, 75, 150, 300, and 600 μg/mL) incubated at 30 °C, 60 rpm for 24 h. After 24 h, the wells were washed twice with 0.2 mL PBS (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 15 min. Crystal violet solution (0.1 mL, 1 mg/mL) was added to each well to allow staining for 5–10 min, then washed with 0.2 mL PBS. The biofilm was dissolved with 0.1 mL 95% ethanol for 30 min and light absorption was measured at OD 595 nm.

Assessment of biofilm metabolic activity

Different concentrations of E-PL were added to the bacterial suspension 1 × 106 CFU/mL, the final E-PL concentration was 0, 9.38 μg/mL, and 18.75 μg/mL, respectively. These mixtures were added to the 96-well plate at 37°C for 6 and 24 h. The cells were cleaned with 1 × PBS buffer three times. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 h using the Cell Couting kit-8 (CCK-8 kit) (Beyotime, Beijing) according to the Manufacturer’s instructions. And the results were measured at OD450 nm.

To determine the impact of E-PL on the metabolic activity of mature biofilm, P. aeruginosa was cultured in 96-well plates for 24 h to form mature biofilm. The followed process as above section described. Different from above, E-PL (0, 600 μg/mL, and 1200 μg/mL) was add to the plates for 6 h. Then, the plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h.

Assessment of biofilm structure

The bacterial suspension (200 μL; 1 × 108 CFU/mL) was added to a 24-well culture plate containing 1.8 mL LB medium at 37 °C and 60 rpm for 24 h. The plate was washed twice with PBS, then fresh medium containing E-PL (150, 300, and 600 μg/mL) was added to the 24-well plate, and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 6 h. The plate was gently rinsed twice with 1 × PBS, and the cell crawling tablets were removed and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 30 min. Then, the plates were dehydrated in turn with 30, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100% anhydrous ethanol for 10–15 min each at room temperature. After the dehydration was complete, the plates were naturally dried, treated with gold spray, and observed by SEM (Regulus 8100, HITACHI, Japan). Scan electron microscopy is carried out with Regulus 15 kV, 12.7 mm × 10.0k magnification.

As described above, the control group (0 μg/mL) and the experimental group receiving E-PL treatment (150, 300, and 600 μg/mL) were removed, respectively. The planktonic bacteria were washed with 0.5% NaCl and stained in the dark for 15 min using an MKBio SYTO 9 Live/Dead bacterial double stain kit (Maokang, Shanghai, China). The staining kit uses green nucleic acid dye (SYTO9) and red nucleic acid dye (propyl iodide PI) to detect bacterial activity. The slides were covered with cover glass and observed under a Fluorescence microscope (DP80, OLYMPUS, Japan). The wavelength of microscopy is 488 and 635 nm to observe live/dead bacterial.

Assessment of bacterial motility

Three types of media were prepared: (1) 0.3% agar medium containing 1.0% tryptone, 0.5% NaCl, and 0.3% agar, (2) semi-solid agar medium with 1% tryptone, 0.5% sodium chloride, 0.8% nutrient agar, and 0.5% glucose, and (3) LB medium with a 1.0% agar layer. The medium was taken from the sterilized pot and added with E-PL (0, 150 μg/mL, 300 μg/mL, 600 μg/mL), then poured into a disposable petri dish and solidified at room temperature. MIC (300 μg/mL) is the minimum inhibitory concentration. The bacteria (1 μL; 1 × 106 CFU/mL) were then inoculated into the center of the agar medium and incubated at 30°C for 24 h. The swimming ability and community dynamics of the bacteria were determined by measuring the circular expansion radius. The bacterial biofilm on the dish was stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet (Beyond, Beijing). The dye was removed by washing with water and puncture movement was observed.

Real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR

The prepared P. aeruginosa suspensions were pre-cultured with 1 × 106 CFU/mL for 24 h, cultured in medium with or without E-PL (300 μg/mL) for 6 h, and the biofilms were collected. Total RNA was extracted from the biofilms using the trizol method follow the manufacturer protocol as described previously (slight modification)49,50,51. In simple terms, 1 mL of TRIzol™ reagent per 0.25 mL of sample (1 ×107 cells of bacterial origin) was added to the pellet. 1 mL trizol was added to the collected biofilm cells, violently shaken to fully lysate the cells, at room temperature for 5 min. 0.3 mL chloroform was add in tubes for lysis. Then the tube was shake thoroughly mix, centrifuge at 4°C, 12000 rpm, 15 min. The supernatant was taken and added 0.5 mL isopropyl alcohol into the test tube, gently mix the liquid at room temperature for 10 min, centrifuge at 4°C, 12000 rpm, 10 min. Then supernatant was discarded and add 1 mL 100% ethanol, centrifuge at 4°C, 12000 rpm, 10 min. The precipitate was dissolved with DEPC H2O.

QuantStudioTM 1 Plus real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used to detect plsA, rhlI, antB, katB, phzS, phzH, and phzM transcription in the E-PL-treated biofilms. Specific amplification primers for all tested genes are listed in Table 1. The final reaction volume was 20 μL, including 10 μL ArtiCanCEO SYBR qPCR Mix, 10 μM primer F, 1 μL e total RNA was extracted ach for the forward and reverse primes, 7 μL ddH2O, and 1 μL of the triple diluted cDNA template. The PCR procedure was 95°C 5 min, 40 cycles (95°C 15 s, 60°C 20 s, 72°C 20 s), 65°C 1 min. Rpod was used as a reference gene to calculate the relative expression of each gene. Three wells were used for each sample. The relative expression of target genes was calculated using the 2−△△Ct method52.

Transcriptome analysis

To further explore the ability of E-PL to regulate gene expression in P. aeruginosa biofilms, transcriptomic analysis was performed on the control and E-PL (300 μg/mL) treated biofilms. The samples were pre-cultured in LB medium for 24 h, and floating bacteria on the surface of the samples were gently washed with PBS. Samples in the control (0 μg/mL) and experimental (300 μg/mL) groups were treated with E-PL for 6 h, and the total RNA was extracted. Transcriptome sequencing was performed with Novogene (Tianjin, China). Libraries of qualified samples were established and sequenced by Illumina. Then, the DESeq2 R package (1.20.0) was used to analyze the differential expression genes (DEGs) of the two groups. Then DEGs were analyzed by using Gene Ontology (GO) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia Gene and Genome (KEGG) analysis of genetic variations (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn). After the differentially expressed genes were analyzed by GO and KEGG (p < 0.05 and log2 fold change > 1 or < 0.7). The genes related to flagella synthesis, chemotactic transduction, biofilm synthesis, transcriptional regulation, phenazine compound synthesis and electron transfer expression were found to form the heatmap.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least three times. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.22.0. Single-factor analysis of variance and Tukey’s test were used for statistical analyses. The figures in this study were generated using Origin 2018.

Responses