The ENaC taste receptor’s perceived mechanism of mushroom salty peptides revealed by molecular interaction analysis

Introduction

Salty peptides are taste-presenting substances with salty properties that can promote the release and enhance the perception of salty taste. They have attracted extensive attention from scholars in flavor peptide research regarding food flavor enrichment and non-sodium salt substitution. The taste presentation activity of salty peptides is closely related to taste receptor recognition. Different taste receptors have different abilities to recognize and bind molecules, and the recognition of binding molecules by taste receptors and intracellular signal transduction depends on intermolecular interactions. Salty taste sensing is complex, and the nerve fibers that transmit salty signals are mainly located in the dorsal-ventral part of the tongue. Epithelial Na+ channels (ENaCs), which act as low salt sensing receptors, are pore-like structures consisting of α, β, and γ subunits, which enhance the brain’s perception of salty taste by stimulating regulatory sites in the finger domains of the receptor subunits and the structural domains of the GRIP in the taste cells to increase the frequency of the Na+-induced response1,2. The perception receptor of salty taste in the human body also includes TRPV1, a receptor member of the transient receptor potential (TRP) channel on the cell membrane, which responds non-specifically to cations such as Na+, K+, and NH4+. The cations pass through the TRP ion channel into the cell to polarize calcium ions. The calcium inward flow prompts the release of neurotransmitters and signal transduction, producing a salty taste sensation3,4. Taste perception studies of NaCl in the gustatory and tympanic gustatory nerves of TRPV1 knockout mice have shown that TRPV1 knockout mice do not exhibit taste perception responses to NaCl in either the absence or the presence of Maillard-responsive peptides (MRPs), and that MRPs are used to regulate taste perception of NaCl in both humans and mice through interaction with TRPV1 to modulate the perceptual response to NaCl5. In addition, the transient receptor potential melastatin 3 (TRPML3)6, transient receptor potential melastatin 5 (TRPM5)7, and transmembrane channel-like protein 4 (TMC4)8, and KV3.2 protein9 have also been identified as potential salty taste receptors. Mice lacking TMC4 are found to have a significantly diminished glossopharyngeal nerve response to high concentrations of NaCl compared to wild-type littermates, and the findings suggest that TMC4 is a chloride channel that is responsive to high concentrations of NaCl10. TMC4 might accelerate the action potential cycles for salty taste signals11. The mining and confirmation of target taste receptors is a crucial step in resolving taste perception, and obtaining the binding structures and activities of salty peptides with different taste receptors is necessary for understanding the receptor recognition and perception of the taste presentation properties of salty peptides.

Mushrooms, due to their salty and umami taste characteristics, have attracted researchers and scholars to study the taste presentation properties of the peptide molecules they contain. The salty taste-enhancing peptides (ADHDLPF, DIQPEER, DEPLIVW, LPDEPSR) isolated from shiitake mushrooms exhibited a synergistic salty-enhancing effect when combined with a NaCl solution at a concentration of 4 g/L. These salty-enhancing peptides can effectively replace 25% to 50% of salt12. Sensory evaluation of the umami peptides (PHEMQ, SEPSHF, SGCVNEL, EPLCNQ, ESCAPQL) isolated from the Stropharia rugosoannulata mushroom showed that PHEMQ and SEPSHF at a concentration of 0.05% exhibited a more robust salty taste profile than a 0.4% salt solution, with intensities equivalent to those of 0.55% and 0.65% salt solutions, respectively. The intensity of the salty taste of SGCVENL was comparable to that of a 0.29% salt solution. When 0.05% NaCl was replaced with umami peptide in a 0.35% salt solution, the salty scores of salt solutions increased. However, the salty enhancement effect of the umami peptides PHEMQ and SEPSHF was not significant, mainly because their own salty intensities were high, and their synergistic effect with NaCl did not linearly increase the perceived salinity but rather reached a saturation point13.

In our previous study, we isolated four salty peptides ESPERPFL (EL-8P), KSWDDFFTR (KR-9P), RIEDNLVIIR (RR-10P), and GQEDYDRLRPL (GL-11P) from S. rugosoannulata mushroom, and the peptides’ salty presenting strengths at a concentration of 1 mg/mL were 1.9-5.3 times that of the same concentration of salt solution. The salty peptide is a better salt substitute. The molecular interaction results showed that the four salty peptides can activate the TRPV1 receptor, and the TRPV1 receptor specifically bound more than two peptide molecules14. Molecular interactions also showed that the TMC4 receptor could only recognize and bind KR-9P and RR-10P, and the number of peptide molecules bound to the receptor ranged from 2 to 4. Both the TRPV1 receptor and TMC4 receptor bind to peptide molecules via their active pocket binding mechanisms (Supplementary Figure 1). In contrast, the different subunits (α, β, and γ) of the ENaC receptor (SCNN1α, SCNN1β, and SCNN1γ) have different electrostatic potentials in the transmembrane portion, various structures of the active pocket, and changes in the receptor structure induced by peptide molecules binding to the receptor’s active sites, all of which affect the receptor’s ability to recognize and sense peptide molecules. How the salty peptides selectively activate different subunits of the ENaC receptor and the binding structures and activities of salty peptides with the ENaC receptor are still unknown. Therefore, studying the selective bias of the ENaC receptor in recognizing salty peptides and analyzing the peptide’s binding structure and binding activity with different ENaC subunits can provide a theoretical basis for understanding the taste properties of salty peptides recognized and perceived by the ENaC receptor.

In this study, the binding reaction types and binding activities of salty peptides with ENaC receptor different subunits were analyzed by molecular thermodynamic and dynamic interactions, the binding sites and modes of the salty peptides and ENaC receptor subunits were studied by molecular docking, and the molecular conformational changes and complex stability during the molecular interaction process between the salty peptide and the ENaC receptor were revealed by molecular dynamics simulation. Through the above results cross-validated, the salty peptides’ perception mechanism by ENaC receptor was clarified.

Results

Molecular thermodynamic interactions assay

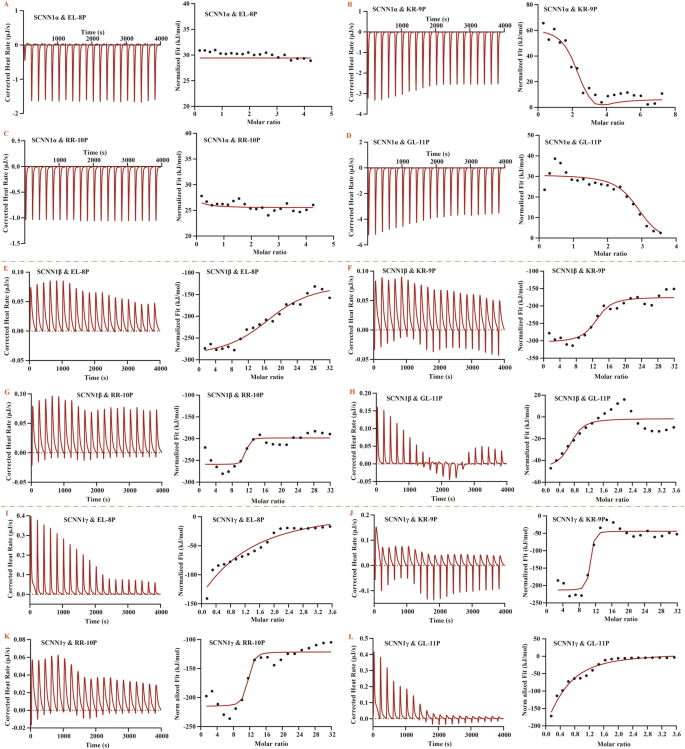

The results of thermodynamic interactions between the four salty peptides and ENaC different subunits are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

A–D thermodynamic interactions between peptides and the SCNN1α receptor; E–H thermodynamic interactions between peptides and the SCNN1β receptor; I–L thermodynamic interactions between peptides and the SCNN1γ receptor.

The results showed that the binding of the salty peptide to the SCNN1α receptor was a reaction process with heat absorption and significant entropy increase (ΔH > 0, ΔS > 0), and the entropy increase effect (TΔS > ΔH) determined the interactions of the salty peptide with the SCNN1α receptor as an entropy-driven binding reaction. From the KD values and stoichiometric values calculated from the fitted curves, it can be seen that GL-11P and KR-9P were moderately bound to the SCNN1α receptor, and the receptor can bind more than one peptide molecule (Table 1, Fig. 1B, D). The equilibrium constants between EL-8P, RR-10P, and the SCNN1α receptor were low, which showed a weak binding, and the number of peptide molecules that the receptor bound to was less than 1, indicating that the active concentration of peptide molecules bound to the receptor (active conformation) was less than 100% (Table 1, Fig. 1A, C). Because there was no competitive combination for multiple peptide molecules or multiple receptors, the weak binding of the salty peptides (RR-10P and EL-8P) to the SCNN1α receptors might be related to the spatial resistance of the peptide molecules or the receptor conformation changes caused by the molecular interaction, in which the hydrophobic portion of the peptide molecules was embedded into the hydrophobic cavity of the SCNN1α receptor, which increased the disorder of the reaction system, and manifested an entropy-driven process dominated by hydrophobic interactions.

The results showed that although α, β, and γ subunits belong to the ENaC taste receptor, the thermodynamic interactions between the SCNN1β and SCNN1γ receptors and the four salty peptides were significantly different from those of the SCNN1α receptor and salty peptides. The enthalpy and entropy values of the thermodynamic interactions between the SCNN1β, SCNN1γ receptors, and salty peptides were negative, manifested as the intermolecular hydrogen bonds interaction forces dominating the spontaneous enthalpy-driven binding reaction.

The molecule number of GL-11P bound to the SCNN1β receptor was less than 1, indicating that the activity concentration of GL-11P was less than 100% (Table 1, Fig. 1H). However, the intermolecular affinity between the SCNN1β receptor and GL-11P was at a high level (9.70 ×10−7 M), which might be the spatial resistance of GL-11P resulted in the whole peptide molecule being unable to bind to the SCNN1β receptor completely, but the residues of GL-11P that bound to the receptor, with lower binding energies, producing a strong binding strength to the SCNN1β receptor. The EL-8P, KR-9P, and RR-10P molecule numbers that the SCNN1β receptor identified and combined were greater than 10, and the intermolecular binding strengths were all high, with the range of thermodynamic affinity constants of 10−8 to 10−7 M (Table 1, Fig. 1E–G).

The molecule numbers of KR-9P and RR-10P bound to the SCNN1γ receptor were comparable to those bound to the SCNN1β receptor, which were more than 10 (Table 1, Fig. 1J, K). The binding strength between the SCNN1γ receptor and the KR-9P and RR-10P was more substantial, with affinity constants an order of magnitude lower than those of the SCNN1β receptor with the two salty peptides, and the affinity constant between the SCNN1γ receptor and KR-9P arrived at a solid binding level (10−9 M). The active concentrations of EL-8P and GL-11P combined by the SCNN1γ receptor were lower than 100%, and the intermolecular binding strength was medium (10−5 M) (Table 1, Fig. 1I, L). The low stoichiometric value also affected the peptide molecules to exert their taste-presenting properties, and the active conformation of GL-11P binding to the SCNN1γ receptor was much lower than its binding to other ENaC subunits.

The thermodynamic interaction results of ENaC different subunits for binding salty peptides showed that the binding strength of the SCNN1α receptor to salty peptide molecules was lower than that of SCNN1β and SCNN1γ receptors, suggesting that salty peptide molecules were more dominant in activating and binding the SCNN1β and SCNN1γ receptors. The activation characteristics of peptide molecules to ENaC different subunits belonged to differential activation, resulting in the ENaC subunits having their tendency to bind salty peptides. The SCNN1β receptor was the subunit that bound more salty peptide molecules among the three subunits. The SCNN1γ receptor had the most vital binding ability to the salty peptides KR-9P and RR-10P. KR-9P had a higher binding number and strength of receptors than the other three salty peptides. The enthalpy-driven reaction was more favorable than the entropy-driven reaction for the combination of peptide molecules to the salty receptors. Our previous study found that the number of different salty peptide molecules bound to the TRPV1 receptor did not differ much (2-3 peptide molecules) in the molecular thermodynamic interactions. The salty peptides were all bound to the active amino acid residue sites in the TRPV1 receptor pockets14. In contrast, the numbers of peptide molecules bound to the SCNN1β and SCNN1γ receptors were much higher than 1, which might be related to the binding of peptide molecules to amino acid residue sites on the receptor surface.

Molecular dynamic interactions assay

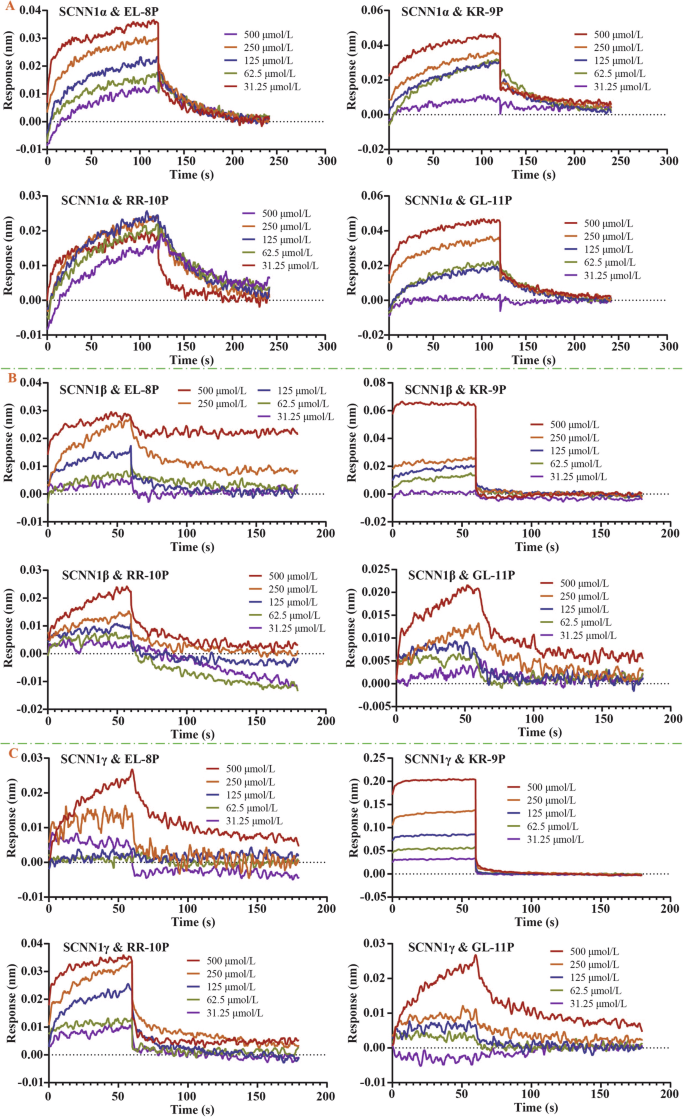

The dynamic interaction results of the salty peptides interacting with the ENaC different subunits at different molar gradients are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2.

A Dynamic interactions between peptides and the SCNN1α receptor; B dynamic interactions between peptides and the SCNN1β receptor; C dynamic interactions between peptides and the SCNN1γ receptor.

The results showed that the binding response signals of the three salty peptides EL-8P, KR-9P, and GL-11P to the SCNN1a receptor showed a dose-dependent enhancement with increased peptide molecule molar concentrations. The intermolecular binding response signals between RR-10P and the SCNN1a receptor at different molar concentrations showed little variability, and the weaker binding signals of the peptide molecules to the SCNN1a receptor at its high molar concentration (500 μmol/L) were related to the decreased solubility of the peptide molecules. The binding strength of GL-11P and KR-9P to the SCNN1a receptors was at the intermediate level. The binding and dissociation constants of the four salty peptides with the SCNN1a receptor indicated that the peptide molecules and the receptor had slow binding and dissociation interaction characteristics. All four salty peptides showed specific binding to the SCNN1a receptor (Table 2, Fig. 2A).

The results showed that the specific binding equilibrium reaction time of the four salty peptides to the SCNN1β receptor was 60 s, one-half of the binding equilibrium time of the peptide molecules to the SCNN1α receptor. At the same molar concentration, the response signal of KR-9P binding to the SCNN1β receptor was higher than that of the other three salty peptides, presumably related to the slow dissociation property of KR-9P from the receptor. The binding affinity of KR-9P to the SCNN1β receptor was also higher than that of the other three salty peptides, which was at a medium strength level. The binding rate of RR-10P to the SCNN1β receptor was slightly lower than that of KR-9P, and the dissociation rate was higher than that of KR-9P, resulting in a lower binding strength to the SCNN1β receptor by RR-10P than that of KR-9P. The dynamic affinity constants of the three salty peptides, EL-8P, RR-10P, and GL-11P, for the SCNN1β receptor were of the same order of magnitude (Table 2, Fig. 2B).

The results showed that the binding equilibrium time of the peptide molecules to the SCNN1γ receptor was consistent with that to the SCNN1β receptor, and the intermolecular specific binding was completed within 60 s. The binding strength of the four salty peptides to the SCNN1γ receptor was higher than that of the peptide molecules binding to the SCNN1α and SCNN1β receptors, and the binding rate of the peptide molecules to the SCNN1γ receptor was higher than that to the SCNN1α and SCNN1β receptors. The dynamic affinity of KR-9P binding to the SCNN1γ receptor was at μM level, which was fast binding and slow dissociation. The affinity of GL-11P binds to the SCNN1γ receptor was higher than its binding strength to the SCNN1β receptor. Although the GL-11P had the highest binding rate to the SCNN1γ receptor, it also had the highest dissociation rate, so the intermolecular binding strength was still moderate (Table 2, Fig. 2C).

In summary, ENaC’s different subunits can specifically recognize and bind four salty peptide molecules. The binding strength and rate of KR-9P to each subunit were higher than that of the other three salty peptides. KR-9P may present the best taste effect during the recognition and binding process of the ENaC taste receptor. Compared with the dynamic interactions of four salty peptides and the TRPV1 receptor14, the dynamic affinity constants of EL-8P and KR-9P binding to the TRPV1 receptor were higher than those of the peptide molecules with the ENaC receptor. The peptide molecules also had the highest binding rate with the TRPV1 receptor, which indicated that the oligopeptide molecules were more advantageous in binding to the TRPV1 receptor. The dynamic affinity constants of RR-10P with the TRPV1 receptor and the SCNN1γ receptor were not much different and slightly higher than those of the peptide molecule with the SCNN1β and SCNN1α receptors. Although the binding rate of RR-10P with the TRPV1 receptor was higher than that of RR-10P with the SCNN1γ receptor, the peptide molecules dissociated from the SCNN1γ receptor with a lower rate, which meant that RR-10P had comparable intensity of taste presentation during recognition and binding to both TRPV1 and SCNN1γ receptors. The binding of GL-11P to the ENaC receptor was more substantial than that of the peptide molecule to the TRPV1 receptor, and the binding levels of GL-11P to the ENaC taste receptor were of moderate strength. It was speculated that in the oral cavity, where multiple taste receptors coexist, peptide molecules might bind rapidly to the TRPV1 taste receptor. They might also bind to the ENaC taste receptor, facilitated by their interactions with multiple sites on the SCNN1γ and SCNN1β receptors. Ultimately, this process leads to a consensus among the multi-taste receptors, enhancing the perception of the salty peptide taste.

Molecular binding modes assay

Table 3 shows the transmembrane regions of the ENaC different subunits predicted by TMHMM. The N-terminal of the ENaC three subunits was located on the membrane’s inner side, and SCNN1α and SCNN1β contained one transmembrane helix, and SCNN1γ contained two transmembrane helices.

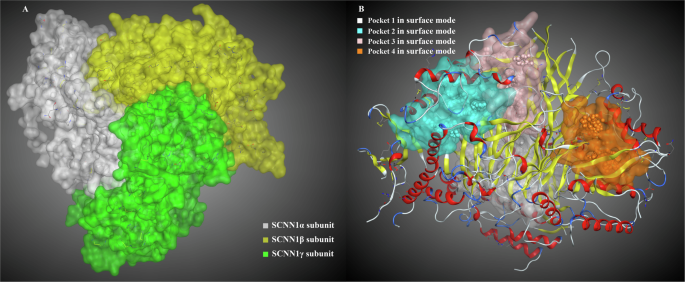

MOE optimized the crystal structure of the ENaC taste receptor. The distribution of ENaC’s three subunits is shown in Fig. 3A. The distribution of the four main active pockets, named pocket 1, pocket 2, pocket 3, and pocket 4, is shown in Fig. 3B. The active amino acid sites in pocket 1 (size, 397 Å3) were mainly distributed in the SCNN1γ receptor, and a small number of residues belong to the α subunit. The active amino acid sites in pocket 2 (size, 217 Å3) and pocket 3 (size, 314 Å3) were mainly distributed in the SCNN1β receptor, and a small number of residues belonged to the γ subunit. The active amino acid sites in pocket 4 (size, 209 Å3) were mainly distributed in the SCNN1α receptor, and a small number of residues belonged to the β subunit. From the above molecular interaction analysis results, it can be seen that the numbers of salty peptide molecules bound to the SCNN1β and SCNN1γ receptors were high, and it was speculated that the peptide molecules might have the possibility of binding to the receptor surface and pockets at the same time. Therefore, the binding mode analysis was carried out to dock salty peptides to the surface and pockets of the SCNN1α, SCNN1β, and SCNN1γ receptors.

A The ENaC different subunits; B the active amino acid cavity pockets.

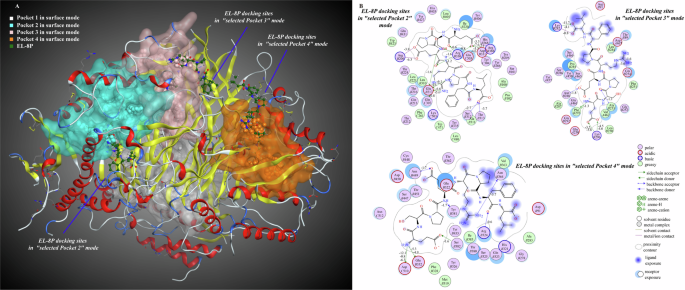

In the all-atom docking mode in which the three ENaC subunits coexist, all of the amino acid residues of EL-8P were bound to the α subunit. Compared to the selection of a specific subunit docking mode (this mode was consistent with the molecular interaction mode of a single receptor and a single peptide molecule), the peptide molecule bound to a single subunit with a strength that was much lower than its binding strength in the all-atom mode (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). The lower the docking scores and binding energies, the more stable the complexes were. When the pocket 1 docking mode was selected, the peptide molecule residues were bound to the SCNN1α and SCNN1γ receptors. When the pocket 2, pocket 3, and pocket 4 docking modes were selected, the peptide molecule could be bound to all or most residues of the SCNN1β receptor. Combined with the multisite binding results of molecular interactions between the SCNN1β receptor and EL-8P, it can be seen that the ability of EL-8P to activate the β subunit was higher than its ability to activate the other two subunits, and the peptide molecule preferentially bound to the amino acid residues of the SCNN1β receptor in pocket 2, pocket 3, and pocket 4, rather than binding to amino acid residues on the receptor surface. In the pocket 2 binding mode, arginine residue R5 in EL-8P formed hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions with GLU217 in the SCNN1β receptor and GLN307 in the SCNN1γ receptor. Glutamate residues E1 and E4, serine residue S2, and leucine residue L8 formed hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions with arginine residues (ARG330, ARG388, and ARG206) and GLU217 in the SCNN1β receptor. In pocket 3 binding mode, arginine residue R5 in EL-8P formed electrostatic interactions with GLU254 in the SCNN1β receptor, and other amino acid residues (E1, S2, E4, L8) in the peptide molecule formed hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions with lysine residues (LYS296, LYS282) and other residues in the SCNN1β receptor. In the pocket 4 binding mode, arginine residue R5 in EL-8P formed hydrogen bonding interactions with the SCNN1β receptor, and other amino acid residues (E1, E4, F7) in the peptide molecule formed hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions with GLU332 in the SCNN1β receptor, ASP510 and other residues in the SCNN1γ receptor. In summary, ARG330, ARG388, GLU217, and LYS296 in the SCNN1β receptor were the primary amino acid residues for ENaC taste receptor recognition and binding EL-8P, and all of the above residues were located in the extracellular domain of the β subunit (Fig. 4A, B, Supplementary Table 2).

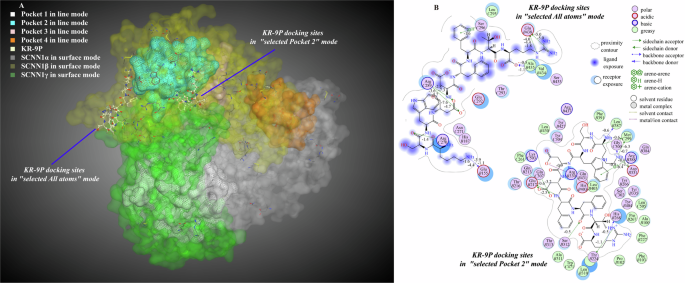

A Molecular interaction 3D view; B molecular interaction 2D view. The numbers on the binding bonds in the 2D plot represented the binding energies.

In the all-atom docking mode, the binding strength of KR-9P bound to the SCNN1β and SCNN1γ receptors did not differ much. When the docking site mode was selected as the SCNN1β receptor, the peptide molecules were bound to the SCNN1α and SCNN1β receptors. This mode’s docking scores and binding bond energies were lower than those of the all-atom docking mode. However, the binding strength of KR-9P bound to the SCNN1α receptor in this mode (binding energy −42.5 kcal/mol) was higher than its binding strength to the SCNN1β receptor (binding energy −38.3 kcal/mol), which was inconsistent with the intermolecular affinity results in the 3.1. The docking results could only indicate that there might be a co-activation property of KR-9P for the two subunits under this docking mode. Combined with the results of high binding sites between KR-9P and the SCNN1β and SCNN1γ receptors, it was speculated that KR-9P had a higher probability of binding the receptor in the all-atom mode (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 3). In the pockets docking mode, the amino acid residues of the SCNN1β and SCNN1γ receptors in pocket 2 formed interactions with KR-9P, and this mode might also be KR-9P’s primary mode of binding ENaC taste receptor. KR-9P produced multisite binding to the SCNN1β and SCNN1γ receptors in binding to the receptor surface atoms and pocket 2 amino acid residues. In both docking modes, the arginine residues R9 in KR-9P were all bound to GLU438 and other residues in the SCNN1β receptor. Except for the T8, amino acid residues in KR-9P bound to GLU155 in the SCNN1β receptor, ARG270, and ARG289 in the SCNN1γ receptor in the all-atom docking mode. In the pocket 2 docking mode, K1 and D5 in KR-9P formed four hydrogen bonding interaction forces with the γ subunit. Other hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, and pi-cation interaction forces were present in K1, W3, D4, D5, F6, and R9 interactions with the β subunit. In summary, GLU155, GLU438 in the SCNN1β receptor and ARG289 in the SCNN1γ receptor were the critical amino acid residues recognized to bind KR-9P, and all of the above amino acid residues were also located in the extracellular domains of their respective subunits (Fig. 5A, B, Supplementary Table 4).

A Molecular interaction 3D view; B molecular interaction 2D view. The numbers on the binding bonds in the 2D plot represented the binding energies.

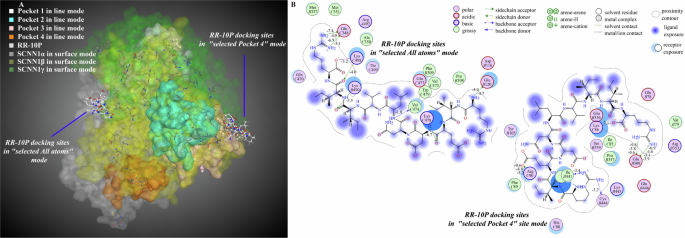

In the all-atom docking mode, RR-10P preferentially bound to the β and γ subunits, and the peptide molecule bound to the γ subunit much more strongly than it bound to the β subunit, which was consistent with the trend of the intermolecular binding strength in 3.1. When the docking mode was selected as a single subunit, RR-10P showed the binding characteristics of interactions with one subunit, and there was no co-activation of the two subunits (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 5). In the active pockets docking mode, the binding of RR-10P to amino acid residues in pockets 2 and 4 was mainly the binding of peptide molecules to β and γ subunits. Still, the binding of RR-10P to the amino acid residues in pocket 2 scored higher and did not have an advantage. When RR-10P was bound to amino acid residues in pocket 4, the peptide molecule did not enter pocket 4. Still, it was embedded in the periphery of pocket 4 and on the surface of the β and γ subunits. Combined with the fact that only a tiny amount of the active amino acid sites in pocket 4 belonged to the β subunit, it was presumed that RR-10P was recognized and bound by the ENaC taste receptor in a mode of co-binding with a small number of β subunit residues in pocket 4 and residues on the surface of the β- and γ-subunits (Figs. 6A, B, Supplementary Table 6). Thus, multisite binding of RR-10P to ENaC taste receptor occurred mainly in all-atom docking mode and pocket 4 docking mode. In the all-atom binding mode, R1 in RR-10P formed one hydrogen bond and one electrostatic interaction force with GLU120 in the β subunit. R10 formed two hydrogen bonds and two ionic interactions with GLU348 in the γ subunit. E3, N5, I8, I9, and R10 formed five hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions with lysine residues in the β- and γ-subunits. In the pocket 4 docking mode, R1 and R10 bound to amino acid residues such as GLU509 and LYS86 in the β and γ subunits, and E3 bound to ARG90 in the γ subunit. The RR-10P binding energies to the β and γ subunits were complementary in both modes, and the total binding energies were less different (−49.4 kcal/mol and −40.0 kcal/mol), consistent with the molecular interaction results. In summary, GLU509 in the β subunit and GLU348 in the γ subunit were the primary amino acid residues in the receptor to recognize and bind RR-10P, and both glutamate residues were located in the extracellular region of the receptor.

A Molecular interaction 3D view; B molecular interaction 2D view. The numbers on the binding bonds in the 2D plot represented the binding energies.

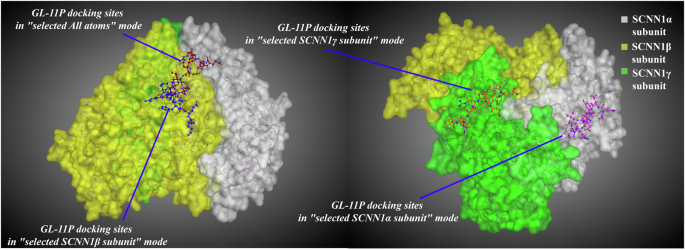

The binding number of GL-11P with ENaC subunits was low. When GL-11P bound to the active amino acid residues of the receptor, the steady-state complexes appeared on the surface of the SCNN1α receptor away from the pocket (selecting the α subunit docking mode) or on the periphery of the pocket 3, at the position of the SCNN1α receptor surface cavity (selecting the pocket 3 docking mode). The docking results showed that GL-11P preferred to bind to amino acid residues on the surface of the SCNN1α receptor (Fig. 7, Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Tables 7, 8). ARG438, ARG508, ASP273, ASP310, and LYS311 were the critical amino acid residues in the SCNN1α receptor for recognizing and binding GL-11P, and the residues were located in the extracellular domain of the receptor.

3D molecular docking plots of salty peptides GL-11P with ENaC taste receptor. The molecular docking on the left was performed using the all-atom docking mode, while the one on the right was performed using a specific subunit docking mode.

In summary, the salty peptide EL-8P preferentially bound amino acid residues in receptor active pocket 2, pocket 3, and pocket 4, KR-9P tended to bind receptor surface atoms and amino acid residues in receptor pocket 2, RR-10P tended to bind receptor surface atoms and amino acid residues in receptor pocket 4, and GL-11P preferentially bound amino acid residues on the receptor surface. The above results reflected the differential binding characteristics of salty peptide molecules to the ENaC different subunits. As the chain of salty peptide molecules extended and the spatial resistance of peptide molecules became extensive, the peptide molecules shifted from receptor pocket binding to receptor surface binding, and the recognition and binding activities of receptor active pocket and surface residues for different peptide molecules were also different. The receptor extracellular arginine, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, and lysine residues were the primary amino acid residues for recognizing and binding salty peptides by the ENaC taste receptor.

Molecular dynamic binding conformations assay

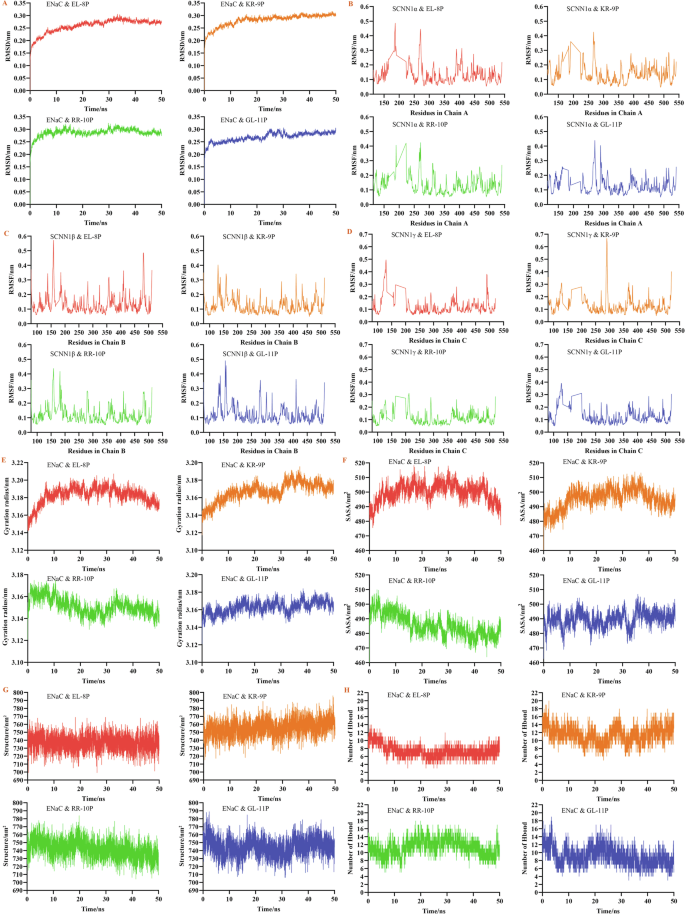

The root means square deviation (RMSD) of the four salty peptides with the ENaC three subunits stabilized after 15 ns, and the RMSD of the complex was 0.3 nm. Between 0–15 ns, the RMSD of the complex formed by RR-10P binding to the receptor fluctuated more, suggesting that the initial binding of RR-10P to the receptor caused structural instability. The RMSD of the binding complex of EL-8P to the receptor fluctuated the least in the 0–15 ns, and the complex was the most stable (Fig. 8A). Comparison of the RMSD values (1.0–1.2 nm) of the salty peptide bound to the TRPV1 taste receptor14, it can be seen that the salty peptide bound more tightly to the ENaC taste receptor.

A The RMSD of binding complex; B–D the RMSF of binding complex; E the gyration radius of binding complex; F the solvent-accessible surface area of binding complex; G the secondary structure of binding complex; H the hydrogen bonds of binding complex.

The salty peptide had a more significant effect on the residues of the ENaC taste receptor. EL-8P significantly affected the α subunit 180–190 and GL-11P on residues near the α subunit 300 (Fig. 8B). The binding of the receptor by EL-8P and GL-11P resulted in higher root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) of amino acid residues in the region of 150–160 region of the β subunit, while EL-8P had a more pronounced effect on the 470–480 region of the β subunit (Fig. 8C). For the γ subunit, after EL-8P binding to the receptor, the amino acid residues in the region 120–130 of the γ subunit fluctuated more, and the peptide molecule had a significant induction of the amino acid residues in the above region. After KR-9P was bound to the receptor, it had a more substantial effect on amino acid residues in the 280–300 region of the γ subunit, and the RMSF of amino acid residues in the region was significantly higher than that in other positions (Fig. 8D).

In summary, after the peptide molecules bound the ENaC taste receptor, EL-8P had a specific effect on the amino acid residues of all three subunits, whereas KR-9P was associated with the amino acid residue fluctuations of the γ subunit and GL-11P with the α and β subunits, which might be related to the types of subunits that the peptide molecules tended to bind. Notably, the initial modeling of the ENaC taste receptor was structurally intact, with no dramatic fluctuations in the receptor protein’s RMSD and RMSF, and the protein’s overall structure was stable. Instead, particular and variable loop regions appeared during the molecular dynamic simulation. Since loop regions were usually located on the surface of proteins and could achieve molecule recognition, binding, and signaling by interacting with small molecules, it was hypothesized that the loop regions that appeared during molecular dynamic simulation played a vital role in the recognition and binding salty peptides by the ENaC taste receptor, which was consistent with the results that peptide molecules were prone to produce receptor-surface binding.

Except for RR-10P, the effects of the other three peptide molecules on the gyration radius of the ENaC taste receptor first increased and then decreased (Fig. 8E). The impact of EL-8P was the most obvious, suggesting that the structure of the peptide molecule-receptor binding complexes gradually changed from unstable to stable. The gyration radius of the protein-bound by RR-10P showed a trend of gradual decrease, suggesting that there was a tendency for the receptor structure to become tighter after the peptide molecule bound to the receptor, which helped to maintain the stability of the protein structure. Similar to the results of the gyration radius, the solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) of the proteins in the three simulations, except for RR-10P, tended to increase during the dynamic simulation process, indicating that the overall conformation of the protein had changed significantly (Fig. 8F). The hydrophilic residues were exposed due to the interaction between the ENaC taste receptor and the peptide molecules. This resulted in the proteins’ structure becoming more open or stretched, and the molecules’ hydrophilicity increased. After RR-10P formed a complex with the receptor, the solvent-accessible area of the protein gradually decreased, the hydrophobicity increased, and the protein structure became more compact or partially obscured. There were no apparent changes in protein secondary structure in any of the four systems (Fig. 8G). Hydrogen bonding was one of the most vital non-covalent binding interactions, and the higher number of hydrogen bonds, the better the peptide bound to the receptor. The higher number of hydrogen bonds formed between KR-9P and the ENaC taste receptor and the lower number of hydrogen bonds formed between EL-8P and GL-11P and the receptor (Fig. 8H). The latter may be related to the lower number of peptide molecules bound to the receptor and proline residues in the peptide unsuitable for bonding.

Discussion

It has been shown that salty substances such as L-arginine could activate and enhance ENaC-mediated sodium currents15 and that the salty taste enhancer arginine dipeptide induced a significant increase in the number of taste cells responsive to NaCl, with a pronounced rise in salty taste perception16,17, and that salty taste enhancers acted in terms of binding to either αβγ or δβγ of the ENaC receptor. In contrast, the enhancement of salty taste perception by γ-glutamyl peptides (GSH and EVG) was not mediated through ENaC receptors18. In the present study, we confirmed that the four salty peptides could activate and bind the α, β, and γ subunits of ENaC by molecular interaction experiments, especially KR-9P and RR-10P had multisite binding advantages in binding the β and γ subunits. The above results indicated that ENaC taste receptor recognize and bind peptide molecules with particular specificity.

Currently, most studies on the perception mechanism of salty peptides are based on molecular docking techniques to study the interactions between salty peptide molecules and taste receptors. Guo et al.19 used molecular docking to explore the binding interactions between collagen glycopeptides and salty taste receptors. The glucosamine residues in the glycopeptide have hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions with ENaC and TRPV1 receptors, and the glycosylation modification sites of collagen glycopeptides can generate more binding sites with salty taste receptors, which may be the reason for the salty taste-enhancing effect of collagen glycopeptides. In addition, molecular docking results showed that acidic and alkaline amino acid residues (Arg, Lys, Asp, Glu, and His residues) in the salty receptors were essential for recognizing and binding glycopeptides. The present study’s results agreed with the results of the above literature.

Ren et al.20 used molecular docking to analyze the binding interactions of salty peptides obtained from tilapia by-product hydrolysates with the TRPV1 receptor. The molecular docking results showed four salty peptides bound to ARG491, TYR487, VAL441, and ASP708 of the TRPV1 receptor through van der Waals force, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interaction force. Xia et al.21 confirmed that γ-glutamyl peptide from Pleurotus geesteranus, bound to the calcium-sensitive receptor CaSR, exerted a salty taste-enhancing effect by molecular docking analysis.

Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation were used to analyze four salty taste-enhancing peptides (ADHDLPF, DIQPEER, DEPLIVW, LPDEPSR) isolated from the enzyme hydrolysis substrates of shiitake mushrooms by Chen et al.12. The results showed that the four saltiness-enhancing peptides could bind to ARG583, ARG294, ALA584, and GLU161 of pocket 1 and ARG437, GLN527, ARG580, and LYS412 of pocket 2 in the salty receptor TMC4. The peptides had a synergistic salty-enhancing effect on NaCl solution and can replace 25%-50% of salt. Wang et al.22 identified the salty peptide KER from bovine bone, and the molecular docking results showed that KER bound to the TMC4 receptor to form hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and electrostatic interaction forces, and the ARG312, GLU319, ALA298, ALA578, PHE156, and GLN155 residues in the receptor played a crucial role in molecular binding. The molecular docking results of salty taste-enhancing peptides, isolated from yeast extracts by Shen et al.8, showed that ARG151, THR148, TYR565, ARG424, ARG330, TYR677, and ARG580 were the primary receptor residues in TMC4 receptor pockets 2 and 4, which bound the amino acid residues (Asn, Glu, and Ser) of the peptide molecules. There have also been some studies that have resolved the salty enhancement effect of umami substances from an umami perspective. Xie et al.23 analyzed the binding of umami peptides derived from Ruditapes philippinarum and ham to the TMC4 receptor through molecular docking. Under neutral conditions (pH 6.5), the umami peptide was in a negative ionic state, which might be the main reason for the umami peptide’s ability to enhance the salty taste. The binding statistics of the five S. rugosoannulata mushroom umami peptides (PHEMQ, SEPSHF, SGCVNEL, EPLCNQ, ESCAPQL) to the amino acid residues in the TMC4 receptor revealed that AGR294, ARG424, ARG580, and THR581 were likely to play major roles in forming hydrogen bonds and ionic interactions during receptor and peptide binding13.

Molecular interaction is used to obtain the actual binding of molecules at the experimental level. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation get molecular binding information at the computer level. These methodologies have been applied to peptide screening for taste or drug target receptors24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. The analysis of intermolecular binding properties through cross-validation of multiple techniques is informative for understanding and elucidating the ENaC taste receptor sensing mechanism of salty peptides. In conclusion, compared with the results of the previous study, the amino acid residues in the intracellular region of the TRPV1 receptor14, which were the critical amino acid residues for the recognition and binding of salty peptides by the TRPV1 taste receptor, and the extracellular amino acid residues in the subunit of the ENaC receptor, which were the critical amino acid residues for the recognition and binding of salty peptides by the ENaC taste receptor. The protein molecules became progressively more hydrophobic after the binding of the peptide molecule by the TRPV1 taste receptor, and the binding of the peptide molecule by the ENaC taste receptor increased the hydrophilicity of the protein molecule. The salty peptide bound more tightly to the ENaC taste receptor than the peptide molecule bound to the TRPV1 taste receptor, and the close and multisite binding of the peptide molecule to the ENaC taste receptor was the main reason the receptor sensed the peptide molecule and enabled it to exert its taste effect. The above results also suggest that different salty receptors’ recognition and binding properties are distinctive for peptide molecules.

The molecular interactions of the salty peptides, EL-8P, KR-9P, RR-10P, and GL-11P, with the SCNN1β and SCNN1γ taste receptors, were spontaneous exothermic enthalpy-driven binding reactions, and the main driving force was the hydrogen bonding interaction force. The salty peptide-binding interactions with the SCNN1α taste receptor were entropy-driven reactions with heat-absorbing and entropy increase. The enthalpy-driven interaction was more favorable than the entropy-driven reaction for the binding of the salty peptide to the ENaC taste receptor, and the molecule number of KR-9P and RR-10P recognized and bound by the SCNN1β and SCNN1γ receptor was higher than 10. As the salty peptide molecular chain lengthened and the spatial site resistance of the peptide molecules became extensive, the peptide molecule binding mode to the ENaC taste receptor shifted from receptor pocket binding to receptor surface binding, with EL-8P preferentially binding to amino acid residues in the receptor active pockets, KR-9P and RR-10P binding to the receptor pockets and amino acid residues on the receptor surface, and GL-11P preferentially binding to amino acid residues on the surface of the receptor. The receptor extracellular arginine, glutamic acid, aspartic acid, and lysine residues were the critical amino acid residues in the recognition and binding of salty peptides by the ENaC taste receptor. The salty peptide-ENaC receptor binding complex was stable around 0.3 nm, and the close and multisite binding of the peptide molecule to the receptor was the main reason the ENaC taste receptor sensed the peptide molecule and enabled it to exert its taste effect.

This study investigated the variability in the activation and binding of the ENaC receptor by different salty peptides found in mushrooms. It provides a scientific foundation for understanding how the ENaC receptor recognize and bind to these salty peptides. However, the molecular mechanisms by which peptide binding activates intracellular signaling at the physiological level remain unclear. Future research should focus on the in-situ conditions of taste cells to gather information about the changes in signal transduction channels caused by the interaction between the receptor and salty peptides. Additionally, it should explore the intracellular messenger molecules involved in the signaling pathway to further clarify how the receptor activation and the recognition of salty peptides contribute to taste enhancement and perception.

Methods

Samples and reagents

Four salty peptides, EL-8P, KR-9P, RR-10P, and GL-11P, were synthesized by Gill Biochemicals (Shanghai) Co. Ltd., and the purity of the synthetic peptides was greater than 98%. Amiloride-sensitive sodium channel protein 1α recombinant protein (SCNN1α, sequence Tyr112 – Thr543, with N-terminal histidine tag), amiloride-sensitive sodium channel protein 1β recombinant protein (SCNN1β, sequence Tyr504 – Ile640, with N-terminal histidine and glutathione S-transferase tag), and amiloride-sensitive sodium channel protein 1γ recombinant protein (SCNN1γ, sequence Thr80 – Thr401, with N-terminal histidine tag) were expressed by prokaryotic expression (Host: E.coli) by Cloud-Clone. The purity of the receptor protein was greater than 90%, and SDS-PAGE determined all receptor protein molecular mass. The accurate molecular mass of SCNN1α is 54 kDa, SCNN1β 45 kDa, and SCNN1γ 41 kDa.

Molecular thermodynamic interactions analysis between salty peptide and ENaC taste receptor

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) was used to analyze the thermodynamic interaction types between the taste receptors (SCNN1α, SCNN1β, and SCNN1γ) and the salty peptides (EL-8P, KR-9P, RR-10P, and GL-11P). The experimental operation method was the same as in the literature14. ITC measured and analyzed the reaction system thermal changes during the intermolecular binding process of the ENaC taste receptor and the salty peptide, and obtained the interaction parameters of the thermodynamic binding affinity (KD), stoichiometric value (N), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS).

Molecular dynamic interactions analysis between salty peptide and ENaC taste receptor

The dynamic interaction mode of the salty peptides and the taste receptors was analyzed using biofilm interferometry (BLI). The experimental procedure was performed as in the literature14. The molar concentration of the biotinylated taste receptor was 1 mmol/L, and the molar concentrations of the salty peptides that interacted with the taste receptor were 31.25 μmol/L, 62.5 μmol/L, 125 μmol/L, 250 μmol/L, and 500 μmol/L. The BLI data analysis software was used to obtain the dynamic binding constants (Kon), dissociation constants (Koff), and affinity constants (KD) during the molecular dynamic interactions.

Molecular binding modes analysis between salty peptide and ENaC taste receptor

The taste ENaC receptor (PDB ID: 6WTH) structure file was downloaded from RCSB PDB (https://www.rcsb.org/). The transmembrane region of the receptor was resolved using TMHMM-2.0 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/). MOE 2019 molecular docking software was used to optimize the taste receptor crystal structure. The 3D structure of the salty peptides was constructed and energy minimized by MOE. The MOE Site Finder module confirmed the receptor’s α, β, and γ subunit active sites and cavity pockets. The docking score, bonding number, and binding energy of the salty peptide bound to the taste receptor were screening indexes to select the tight binding complexes, and the MOE software analyzed the binding sites and modes between the salty peptide and the ENaC taste receptor.

Molecular dynamic binding conformations analysis between salty peptide and ENaC taste receptor

Molecular dynamics simulation analysis of salty peptide and the ENaC taste receptor interaction was performed by GROMACS 2022.3. The molecular dynamics simulation method was the same as the literature39. The molecular dynamics simulation time was determined to be 50 ns from the pre-experimental results. The changes in receptor conformation, amino acid residue fluctuations, radius of gyration, and intermolecular hydrogen bonding were analyzed by GROMACS software.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9 software was also used to plot the ITC, BLI, and GROMACS collection data. MOE software was used to process the molecular docking data.

Responses