The epigenetic basis of hepatocellular carcinoma – mechanisms and potential directions for biomarkers and therapeutics

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer, the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer, and the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. The incidence and mortality of HCC are projected to grow by more than 50% over the next two decades if global rates remain unchanged [1].

The early detection of HCC is presently suboptimal. The prevailing protocol for high-risk patients typically includes biannual abdominal ultrasounds supplemented by serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) testing [2]. However, the sensitivity for detecting early-stage HCC is only 47% with ultrasound alone, improving modestly to 63% when combined with AFP measurements [3]. This underscores the critical need for more precise diagnostic biomarkers to detect early-stage HCC reliably.

Furthermore, HCC remains a formidable clinical challenge, with a dismal 5-year survival rate of just 18%. For advanced HCC, curative options are no longer feasible. Systemic cytotoxic chemotherapy has proven largely ineffective due to the dual burden of tumor progression and underlying chronic liver disease, which predisposes patients to hepatotoxicity and myelotoxicity [4]. Recent advances in systemic therapies have offered some hope. The combination of the programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor atezolizumab and the vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) inhibitor bevacizumab (atezo-bev) has become a recommended first-line therapy for advanced HCC, alongside the dual checkpoint inhibitor combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab (durva-treme) [5]. These therapies marked a step forward in HCC management, providing modest improvements in survival. For instance, atezo-bev therapy achieves a 67.2% 12-month overall survival (OS) and a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 6.8 months, compared to 54.6% 12-month OS and 4.3 months PFS with the previous standard, sorafenib [6]. However, these outcomes underscore the limited efficacy of current systemic treatments, with many patients deriving only incremental benefits. For patients contraindicated for or failed atezo-bev or durva-treme, options like sorafenib, lenvatinib, or nivolumab plus ipilimumab are available, but they too fail to substantially improve survival outcomes [7]. This persistent therapeutic gap highlights the critical need for innovative approaches and a deeper understanding of HCC’s cellular and molecular biology.

The study of cancer epigenetics and its clinical applications have gained exponential popularity in recent decades. Epigenetics is the study of stable and heritable gene expression changes without any mutations to the DNA sequence [8]. The changes are primarily governed by mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone post-translational modifications, remodeling of nucleosome positioning, and RNA interferences [9]. Epigenetic aberrations can disrupt normal cell regulation by upregulating proto-oncogenes or inactivating tumor suppressor genes, leading to uncontrolled cancer cell division and growth, chronic inflammation, and tissue fibrosis. Such disruptions often culminate in further local invasion and distal metastasis [10]. Numerous studies have established a causal relationship between epigenetic alterations and both the initiation and progression of cancer [11, 12]. This has sparked a significant debate, suggesting that cancer may not solely be a consequence of genetic mutations but could also arise from epigenetically-driven mechanisms that promote tumorigenesis [13]. Currently, epigenetic reprogramming is recognized as a critical emerging hallmark of cancer and a pivotal factor that enables the acquisition of other cancer hallmarks [14].

Studying the epigenetics of HCC opens the potential to develop early diagnostic biomarkers and avenues for targeted therapy. Using circulatory biomarkers with epigenomic alterations linked to the tumorigenesis of HCC can potentially detect HCC early and predict treatment response. In contrast to genetic mutations, epigenetic alterations are dynamic and reversible. Targeting epigenetic aberrancies and reversing them could be a potential treatment option for HCC [10].

This review aims to highlight the latest knowledge and gaps in HCC epigenetics. The potential areas of applications of epigenetics as biomarkers and therapeutics targeting HCC are also discussed.

Epigenetic Alterations in HCC

HCC development is a multistep and chronic process, often beginning with preneoplastic fibroinflammatory changes that lead to low-grade and high-grade dysplastic hepatocytes, progressively advancing to HCC [15]. Several extrinsic factors predispose these dysplastic hepatocytes to malignant transformation, including viral hepatitis [16, 17], gut microbiome alterations [18], a hypoxic tumor microenvironment [19], and metabolic disturbances [20]. These factors often induce epigenetic alterations that are pivotal in tumor initiation. In preneoplastic lesions, key epigenetic changes include multistep hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes such as APC and RASSF1A, alongside aberrant CpG island hypermethylation, as demonstrated by studies from Lee et al. [21] and Um et al. [22] Conversely, global hypomethylation of oncogenes, coupled with reductions in suppressive histone marks such as H3K9me3, disrupts the epigenetic equilibrium and amplifies oncogenic pathways, particularly in fibrotic livers [23].

Further insights into the extrinsic predisposing events and molecular mechanisms underlying preneoplastic HCC can be explored in studies beyond the scope of this review. The subsequent sections will focus on a detailed exploration of epigenetic aberrations, including DNA methylation, post-translational histone modifications, chromatin remodeling, and the role of non-coding RNAs in the pathogenesis of HCC [15, 24, 25].

DNA methylation in HCC

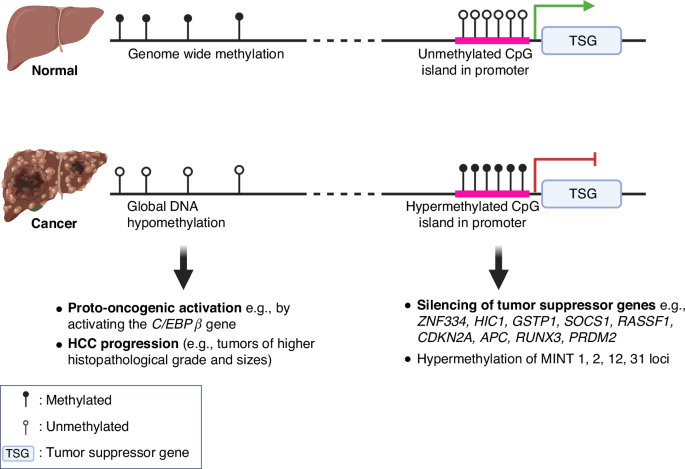

DNA methylation is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), which typically involve the covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosine at the C5 position to form 5-methylcytosine (5mC) in CpG dinucleotides [26]. Conversely, the removal of the methyl group from cytosine is mediated through the enzymatic activity of the ten-eleven translocation (TET) family of dioxygenases (TET1, TET2, and TET3), which hydroxylate 5mC to form 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), a precursor in the active DNA demethylation pathway [27]. In HCC, these regulatory systems are disrupted: DNMT1 and DNMT3b are overexpressed [28], while TET1 and TET2 are downregulated [29, 30]. These mechanisms, along with other complex pathways, contribute to two main patterns of DNA methylation in HCC that are strongly evidenced: (1) global hypomethylation in cancer cells relative to the normal cells and (2) focal hypermethylation of the promoters of tumor suppressor genes [31]. (Fig. 1)

In non-cancerous hepatocytes, the genome-wide methylation and relatively unmethylated CpG island in the promoter of tumor suppressor genes suppress oncogenic expression and enable the expression of tumor suppressive pathways, respectively. In contrast, HCC is characterized by global hypomethylation, which may lead to the activation of oncogenes, e.g., the C/EBPβ gene, contributing to tumor progression as demonstrated by greater histopathological grades and tumor sizes. Additionally, hypermethylation at the promoter regions results in the silencing of tumor suppressor genes, e.g., ZNF334, HIC1, GSTP1, SOCS1, RASSF1, CDKN2A, APC, RUNX3, PRDM2. Hypermethylation at genomic regions known as methylated-in-tumor (MINT) 1, 2, 12, 31 loci are associated with hepatocarcinogenesis. These methylation changes underscore the complex regulatory mechanisms that drive the transition from normal liver function to malignant transformation.

Global hypomethylation of DNA

It has been established that approximately 80% of the CpG sequences in the genome of normal cells are methylated, whereas in tumor cells, this methylation is significantly reduced, with only about 40–60% of CpG sequences methylated [32]. This difference in methylation patterns becomes particularly relevant in the context of HCC, as the overall genomic 5-methylcytosine (5-mC) content is markedly lower in HCC compared to non-HCC liver tissues, suggesting a notable alteration in methylation patterns associated with malignancy [33]. Interestingly, this reduction in methylation is not observed when comparing normal liver to cirrhotic liver tissues [33], challenging the previously held belief that DNA hypomethylation contributes directly to the initial stages of HCC tumorigenesis [33]. Typically, other cancers show a progressive decrease in DNA methylation as they advance from normal to pre-cancerous and, finally, to cancerous stages [34]. Furthermore, the extent of genomic demethylation is particularly pronounced in HCCs with higher histopathological grades and larger tumor sizes, indicating a correlation between DNA hypomethylation and more advanced disease states [33]. These suggest that while hypomethylation may not initiate tumorigenesis, it appears to play a significant role in the progression of HCC. Correspondingly, approximately 230 hypomethylated gene promoters that are overexpressed reportedly enhanced the development and progression of HCC [35]. Significantly, hypomethylation at the enhancer regions of the C/EBPβ gene led to global transcriptional activation of several oncogenes in HCC [36]. Collectively, these findings underscore the critical role of DNA hypomethylation in both the progression of HCC, possibly through increasing the accessibility and activation of oncogenes in HCC.

DNA hypermethylation

The hypermethylation of tumor suppressor gene promoters is a significant epigenetic alteration contributing to HCC progression. This process blocks transcription factors from accessing DNA, thereby suppressing gene expression that is critical for cell growth regulation and cancer prevention. For instance, the hypermethylation of the ZNF334 gene promoter inhibits its expression to control cell cycle and apoptosis [37]. Further investigations into HCC have shown an increase in methylation of CDKN2A, leading to cell cycle dysregulation [38]. Additionally, several Methylated-in-Tumor (MINT) loci – specifically MINT1, 2, 12, and 31 are found to be not only prevalent in HCC but also linked to various other cancers, suggesting a broader oncogenic role [38]. Moreover, research has identified that early stages of HCC are characterized by significant hypermethylation across a panel of tumor suppressor genes, including HIC1, GSTP1, SOCS1, RASSF1, APC, RUNX3, and PRDM2 [39]. These findings emphasize the profound impact of DNA hypermethylation on the silencing of tumor suppressor genes in HCC, with its upstream molecular drivers in HCC remaining to be explored.

Post-Translational Histone Modifications in HCC

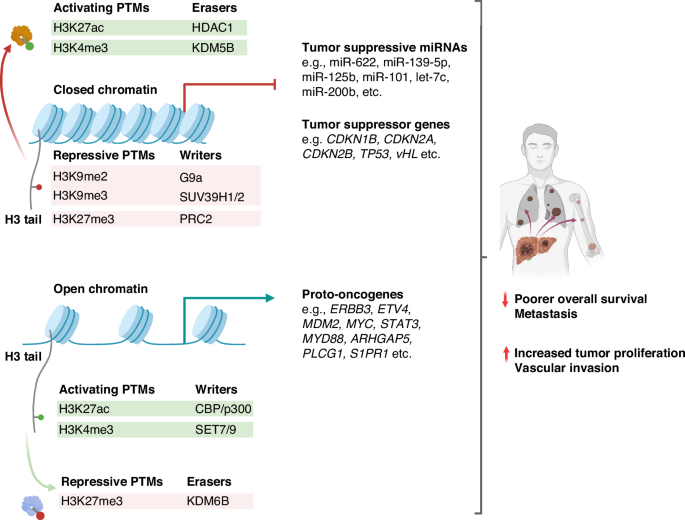

Lysine acetylation and methylation represent quintessential histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) pivotal in gene regulation, as detailed in this review (Fig. 2). The delicate equilibrium between the addition of PTMs by writers (acetyltransferases and methyltransferases) and their removal by erasers (deacetylases and demethylases) is crucial for maintaining regulated gene expression [40].

PTMs contribute to aberrant oncogenic upregulation and tumor suppressor gene repression that characterizes HCC. Activating histone PTMs (e.g., H3K27ac, H3K4me3) and erasers of repressive PTMs (e.g., KDM6B) facilitate open chromatin, leading to proto-oncogene upregulation, thereby promoting hepatocarcinogenesis. Conversely, the downregulation of tumor suppressor genes and miRNAs can be attributed to changes in chromatin accessibility induced by repressive PTMs (e.g., H3K9me2, H3K9me3, H3K27me3). Moreover, various erasers of PTM (e.g., HDAC1, KDM5B) suppress key tumor-suppressive pathways by removing activating methylation or acetylation marks. Overall, these result in increased tumor proliferation, vascular invasion, distal metastasis, and poorer overall survival.

Dysregulation of the writers and erasers of PTMs are evidenced in HCC. Acetylation of lysine residues of histone tails by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) neutralizes their positive charge, which weakens their electrostatic attraction with the negatively-charged DNA, thus increasing DNA accessibility to transcription machinery. Conversely, histone deacetylases (HDACs) restore this charge by removing acetyl groups, thus condensing chromatin structure and reducing gene expression. The specific contributions of these mechanisms to HCC development are summarized in Table 1 for acetylation [41,42,43,44,45,46] and Table 2 for deacetylation [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. In histone methylation, the functional implications of histone methylation are highly variable and dependent on the type of modification and cellular context, with oncogenic implications outlined in Table 3 [42, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64] and 4 [65,66,67,68,69] for methylation and demethylation, respectively. PTMs that contribute to aberrant oncogenic upregulation and tumor suppressor gene repression that profoundly shape carcinogenesis are discussed below.

Activating Histone PTMs upregulate oncogenes in HCC by altering chromatin conformation to increase transcriptional accessibility

Chromatin structure can undergo certain PTMs to increase the accessibility of oncogenes, thereby enhancing the transcriptional accessibility of oncogenic sequences and promoting the progression of HCC. Notably, the augmentation of histone acetylation, such as the acetylation of histone H3 lysine K27 (H3K27ac) and the trimethylation of H3K4 (H3K4me3) at oncogene promoters frequently lead to their overexpression. For instance, H3K27ac, facilitated by the acetyltransferases CBP/p300 [41], has been implicated in the upregulation of oncogenes like ERBB3, ETV4, and MDM2, which in turn drive cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis in HCC cell lines [42]. Moreover, overexpression of SMYD3, a methyltransferase responsible for H3K4me3, has been linked to the elevated expression of key proto-oncogenes such as MYC, CTNNB1, and STAT3, as well as the CDK2 gene, all of which are associated with increased tumor size and intrahepatic metastasis in murine models of HCC [58, 60]. A comprehensive histone modification screen across HCC cell lines further corroborated these findings, showing that high levels of H3K4me3 correlated with the upregulation of proto-oncogenes MYD88, ERBB3, ARHGAP5, and PLCG1 [42]. Additional human studies highlighted the role of H3K4me3-mediated S1PR1 expression in activating downstream oncogenic signaling pathways such as PI3K-Akt, JAK-STAT, and MAPK signaling, culminating in enhanced HCC proliferation, metastasis, and reduced survival [59]. In addition, erasers such as KDM6B remove specific repressive PTMs by demethylating H3K27me3, which upregulates the SLUG gene. This promoted epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), HCC migration, invasion, and cancer stemness, which were linked to shorter OS [69]. Significantly, a recent landmark study on Drosophila unveils that the transient reduction of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) leads to irreversible activation of oncogenic pathways and constitutive malignant transformation despite restoring normal PRC2 levels. This finding suggests that epigenetic histone PTMs may play a crucial role in initiating self-sustaining carcinogenesis at an early stage [70]. While these dynamics have not yet been explored in HCC, investigating whether brief chromatin modifications can lead to lasting oncogenic changes holds substantial promise for developing targeted therapeutic interventions. Overall, these insights into histone modification-mediated oncogene activation elucidate critical pathways in HCC pathogenesis.

Closed chromatin at tumor suppressor loci in HCC results from enhanced activity of erasers, coupled with the downregulation of activating histone PTMs and the upregulation of repressive histone PTMs

HCC development is intricately linked to the dysregulation of histone modifiers that fundamentally restrict chromatin accessibility at certain tumor suppressor genes. This epigenetic reprogramming is underpinned by three key mechanisms: the upregulation of histone PTM erasers, the downregulation of activating histone PTMs, and the enrichment of repressive histone PTMs. Together, these alterations establish a transcriptionally repressive chromatin environment that silences critical regulatory tumor suppressor genes, thereby facilitating oncogenesis.

The upregulation of histone PTM erasers plays a pivotal role in HCC development by restricting accessibility to tumor suppressor genes and silencing their expression. Among these key players, histone deacetylases (HDACs) and specific histone demethylases are critical in reducing chromatin openness, thereby repressing transcription.

Histone deacetylases, particularly HDAC1, have been shown to deacetylate H3K27ac at enhancers of tumor suppressor genes such as TP53, vHL, and the FBP1 genes, leading to their downregulation [48, 49]. This repression is associated with more aggressive HCC phenotypes, including portal vein invasion, higher tumor grade, advanced TNM staging, and reduced OS [47]. Moreover, HDAC1 contributes to the Warburg effect, enhancing HCC proliferation [48]. Furthermore, HDAC1, along with HDAC2 and HDAC3, suppresses miR-449a, a critical inhibitor of c-Met mRNA, thus fostering HCC proliferation [50]. Beyond HDAC1, other HDACs, such as HDAC8 and HDAC9, also play distinct roles in HCC. HDAC8 represses apoptotic pathways by downregulating apoptotic proteins such as BAX, BAD, BAK, caspase-3, and PARP [54], while HDAC9 induces fibroblast-growth-factor-receptor-4 (FGFR4) [71].

Similar to HDACs, specific histone demethylases such as lysine-specific histone demethylase 1 (LSD1, i.e., KDM1A) and KDM5B are implicated in HCC progression. KDM1A demethylates the activating mark H3K4me1/2, silencing tumor suppressor genes such as PRICKLE1 and APC genes, contributing to HCC stemness and chemoresistance [65]. Likewise, upregulation of KDM5B in HCC demethylates the H3K4me3 promoter mark and downregulates the CDKN2B and CDKN1B genes, thereby reducing the expression of p15 and p27 proteins and leading to unchecked HCC proliferation [68].

Collectively, the upregulation of histone PTM erasers, such as HDACs and specific histone demethylases, exemplifies the multifaceted epigenetic dysregulation in HCC. By repressing tumor suppressor genes and apoptotic pathways while fostering stemness and proliferation, these enzymes create a permissive environment for tumor growth and resistance to therapy,

Furthermore, the diminished expression of activating PTM writers, which typically increases chromatin accessibility, contributes to HCC by suppressing tumor-suppressive pathways. For example, the p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF), which acetylates histone H4 lysine K8 (H4K8ac) [72], is downregulated in HCC, enhancing the PI3K-Akt pathway, which inhibits apoptosis and promotes cell proliferation. [43] Reduced PCAF expression also contributes to HCC resistance against 5-fluorouracil through the overexpression of the GLI1/Bcl-2/BAX pathway [44, 73]. This loss of activating PTM writers exemplifies the epigenetic disruption that silences tumor suppressor networks and fosters a cellular environment conducive to tumor growth and developing therapy resistance.

Conversely, the upregulation of repressive histone methyltransferases, such as PRC2, G9a, and SUV39H1/2, reinforces tumor progression by depositing repressive histone marks. PRC2 promotes the trimethylation of histone H3 lysine K27 (H3K27me3) [74], which is correlated with increased tumor size [55], locoregional invasion [75], and poor prognosis [56]. Mechanistically, H3K27me3 represses the expression of key tumor-suppressive microRNAs such as miR-622, miR-139-5p, miR-125b, miR-101, let-7c, and miR-200b [75], thereby silencing critical anti-tumor pathways. Similarly, G9a facilitates the mono-/di-methylation of histone H3 lysine K9 (H3K9me1/2) [61], silencing tumor suppressor genes such as RARRES3 [61] and Bcl-G [62] tumor suppressor genes. Also, G9a overexpression is associated with poor clinical outcomes of HCC [76]. Further exacerbating this repressive epigenetic landscape, SUV39H1/2 mediates the trimethylation of histone H3 lysine K9 (H3K9me3) [77], effectively silencing CDKN2A, a critical gene encoding p16 that regulates the cell cycle [78]. This led to unchecked HCC proliferation and is associated with poor prognosis [77]. Hence, these repressive histone modifications orchestrate a repressive chromatin state, transcriptionally silencing tumor suppressor genes and underpinning tumor growth and invasiveness.

Altered Expression of Epigenetic Readers Contributes to HCC

Epigenetic readers, key interpreters of histone modifications, play a pivotal role in regulating transcription by recruiting co-activators or co-repressors to specific genomic regions. Alterations in their expression disrupt these processes, creating a permissive epigenetic landscape that fosters tumor progression [79]. Among the emerging epigenetic readers of significance in HCC are bromodomain-containing proteins, which recognize acetylated lysine on histones and are often linked to oncogenic activation. Notably, Bromodomain-containing protein 9 (BRD9) is frequently overexpressed in HCC [80], which reportedly upregulates the Wnt/β-catenin [81] and TUFT1/AKT [82] pathways, enhancing tumor aggressiveness and correlating with poorer patient prognosis. Similarly, BRD4, another bromodomain reader, drives the transcriptional activity of NF-κB [83], a critical regulator of inflammation and tumor proliferation, further linking its upregulation to HCC progression and adverse clinical outcomes [84]. The dysregulation of these readers not only underscores their central role in epigenetic control but also positions them as promising therapeutic targets to disrupt oncogenic transcriptional programs and improve HCC treatment strategies.

Spatial Organization of DNA and Distal Chromatin Interactions in HCC

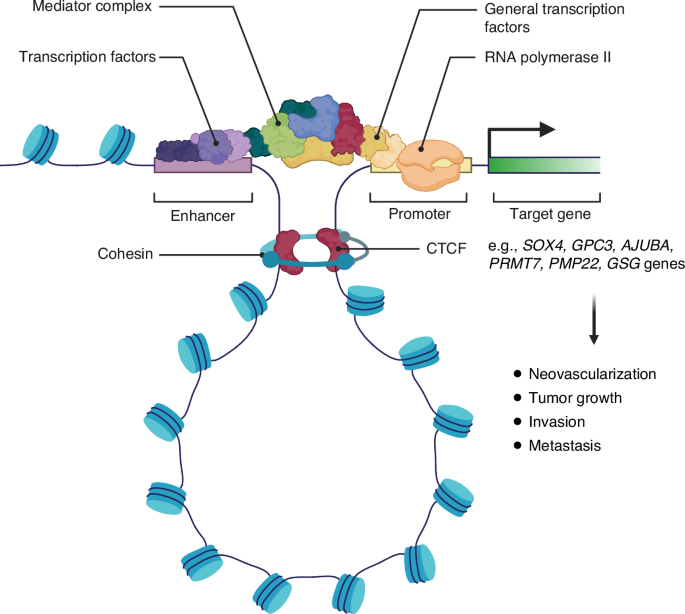

Chromatins are arranged in special three-dimensional (3D) territories within the nucleus in a non-random manner [85]. The formation of chromatin loops may enable gene promoter and distal enhancer interactions [86]. Some examples of altered chromatin architecture and aberrant distal interactions observed in HCC are summarized in Fig. 3.

In some cases of HCC, aberrant chromatin loop formation brings de novo distal enhancers in close proximity to the promoter of several proto-oncogenes. The chromatin loop is stabilized by the CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) and the cohesin complex to facilitate gene transcription. These interactions are associated with increased neovascularization, tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis in HCC.

Genome-wide epigenetic and chromatin profiling studies reveal that HCC is characterized by a significant rearrangement of active enhancers and chromatin loops, with increased deposition of H3K27ac at tumor-specific enhancers and a higher prevalence of chromatin looping compared to adjacent normal tissues [87]. These architectural changes facilitate the upregulation of oncogenic drivers such as SOX4 and GPC3 [87], with SOX4 promoting tumor neovascularization and metastasis [88], while GPC3 activates Wnt signaling to drive HCC growth [89].

Further studies have revealed that the chromatin conformation in HCC often exhibits increased ectopic distal interactions between super-enhancers and oncogenic promoters, increasing their expression. The mechanisms underlying super-enhancer acquisition in cancer include chromosomal translocations that reposition super-enhancer elements [90], disruptions to the structure of insulated chromatin loops [91], and the aberrant formation of transcription factor binding clusters that establish super-enhancers [92]. Tsang et al. highlighted the markedly altered super-enhancer landscape in HCC, showing gains of super-enhancers at the promoters of key oncogenes such as SPHK1, MYC, MYCN, SHH, and YAP1, resulting in their transcriptional upregulation [93]. Additionally, increased super-enhancer interactions have been shown to upregulate the AJUBA gene, activating the Akt/GSK-3β/Snail signaling pathway and promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), thereby driving tumor invasiveness [94]. These findings underscore the critical role of super-enhancer dynamics in reshaping the oncogenic transcriptional landscape in HCC.

Additionally, disruptions in chromatin organization, such as A/B compartment switching and alterations in topologically associating domains, have been observed. These changes can result in the overexpression of genes like PMP22 and GSG, driving HCC invasion and metastasis [95].

Collectively, these findings highlight the profound impact of chromatin conformation dynamics through the interplay of increased enhancer-promoter interactions and chromatin architectural aberrations in reshaping the oncogenic transcriptional landscape of HCC.

Epigenetic regulations by RNAs in HCC

Mechanisms of epigenetic regulations by RNAs

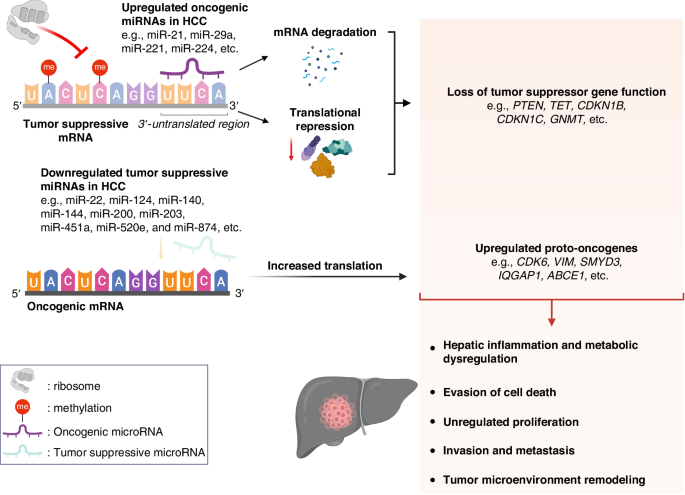

RNA regulates the epigenetic expression of DNA mainly by the following mechanisms: 1) direct interference of mRNA translation to proteins by miRNAs [96] and 2) epitranscriptomic modifications of RNA [97] (Fig. 4). The direct interference on mRNA translation by miRNAs, which bind to the 3′ untranslated region (3’-UTR) of mRNAs, hinder ribosomal translation and degrade mRNAs. Aberrant expression of miRNAs can result in carcinogenesis by hindering tumor suppressor gene expression and increasing proto-oncogene expression [98, 99]. Additionally, epitranscriptomic RNA modifications in the form of internal chemical modifications of the mRNA nucleotides without any changes to the nucleotide sequences contribute to the epigenetic regulation of gene expression by altering how mRNA is translated to proteins [100].

In HCC, direct miRNA interference contributes to HCC in two mechanisms. Firstly, oncogenic miRNAs degrade tumor-suppressive mRNAs and inhibit ribosomal translation. Secondly, tumor-suppressive miRNAs, which normally suppress the expression of proto-oncogenes in normal cells, are downregulated in HCC. Additionally, some epitranscriptomic changes include hypermethylation of tumor suppressor mRNA, which hinders ribosomal translation. Interestingly, hypomethylation of tumor suppressor mRNA can result in a loss in function through destabilization and degradation of mRNA. These result in increased translation of oncogenic mRNAs. Altogether, these might lead to HCC development through hepatic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, evasion of cell death, unregulated proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and tumor microenvironment remodeling that favors hepatocarcinogenesis.

Epigenetic aberrancies caused by RNAs in HCC

miRNA dysregulations, through the upregulation of oncogenic miRNAs and the downregulation of tumor-suppressive miRNAs, have been widely reported in HCC tumorigenesis and progression.

Oncogenic miRNAs (e.g., miR-21, miR-29a, miR-221, and miR-224), which inhibit the expression of tumor suppressors, were reported to be elevated HCC. Here, Cao et al. reported that miR-21 suppressed the expression of PTEN, PTENp1, and TET genes in HCC cell lines [101]. Additionally, Fornari et al. studied miR-221, which suppressed the expression of CDKN1B/p27 and CDKN1C/p57 and, in turn, inhibited HCC cell cycle regulators in vitro [102]. Furthermore, Hung et al. investigated miR-224 in HCC cells and discovered that it inhibited the expression of GNMT, resulting in hepatic inflammation and metabolism disruption [103]. Finally, Chen et al. found that miR-29a silenced the TET-SOCS1-MMP9 axis in vivo and in vitro. This reduced 5-hydroxymethylcytosine levels, which correlated with higher levels of metastasis, shorter OS, and poorer recurrence-free survival in HCC patients [104]. Altogether, these oncogenic miRNAs led to increased HCC tumor proliferation, growth, metastasis, and poor clinical outcomes.

Tumor-suppressive miRNAs (e.g., miR-22, miR-124, miR-140, miR-144, miR-200, miR-203, miR-451a, miR-520e, and miR-874), which normally inhibit oncogenic expression in normal cells, were found to be downregulated in HCC. To highlight this, Zhang et al. found that reduced levels of miR-22 increased HCC cell proliferation by upregulating HDAC4 [105]. Additionally, Furuta et al. used HCC cell lines with benign liver tissues as controls and found reduced expression of miR-124 upregulated CDK6, VIM, SMYD3, and IQGAP1. Also, reduced miR-203 levels upregulated ABCE1. These activated pathways led to HCC growth and metastasis [106]. Moreover, Yan et al. used murine models and reported reduced miR-140-5p expression resulted in overexpression of Pin1-mediated cancer pathways, such as cyclin D1, CDK2, Akt, ERK, and NF-κB [107]. Similarly, Zhang et al. discovered that miR-520e levels are significantly lower in human HCC tissues compared to benign liver tissues. They further elaborated that reduction in miR-520e upregulated the NIK/p-ERK1/2/NF-κB proliferative pathway in vitro [108]. Also, Zhao et al. studied miRNA expression in human HCC and reported downregulation of the miR-144/miR-451a cluster, which upregulated the hepatocyte-growth-factor and macrophage-migration-inhibitory-factor. These facilitated the polarization of M1 macrophages to M2 tumor-associated macrophages, remodeling the tumor immune microenvironment that promoted HCC initiation and proliferation [109]. Another study discovered that suppression of miR-200 in human HCC tissues was associated with EMT and metastasis [110]. Finally, Zhang et al. reported that suppression of miR-874 in HCC cell lines upregulated the DOR/EGFR/ERK pathway. Suppression of miR-874 was associated with increased tumor size, grade, and vascular invasion, as well as poorer overall and recurrence-free survival [111]. The downregulation of tumor-suppressive miRNAs may contribute to HCC development through various mechanisms, including the promotion of proliferative pathways and remodeling of the tumor immune microenvironment, ultimately driving HCC growth, invasion, and poorer clinical outcomes.

Additionally, emerging evidence highlights the pivotal role of epitranscriptomic RNA modifications in the transcriptional aberrancies underlying HCC. While the broader field of RNA modifications remains to be further investigated and is extensively discussed elsewhere [97, 112, 113], key findings specific to HCC warrant attention. One notable example is NSUN7, which encodes the RNA methyltransferase responsible for the 5-methylcytosine (5mC) modification [114]. Recent studies have shown that NSUN7 is silenced in HCC cell lines, and its absence has profound downstream effects. The stability of CCDC9B mRNA, a regulator of the MYC proto-oncogene, relies on 5mC modification [114]. When hypomethylated, CCDC9B mRNA destabilizes, leading to the overexpression of MYC, a well-established driver of oncogenesis [114]. Similarly, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modifications, mediated by METTL enzymes like METTL3 and METTL14, suppress tumor suppressor genes such as SOCS2 [115]. This promotes HCC proliferation in vivo and in vitro, correlating with poorer outcomes. While the epitranscriptomic machinery remains largely under-explored, their potential as therapeutic targets positions this field as an exciting frontier in HCC epigenetics.

Crossroads Between Epigenetic Changes and Etiological Factors in HCC

Epidemiological studies previously established several significant risk factors of HCC, such as viral hepatitis, fatty liver disease, and aflatoxin exposure [116]. Viral hepatitis is presently the most prevalent risk factor for HCC, with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection being more common in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, while hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is more common in the West [116]. However, the prevalence of fatty liver is rising, especially those due to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), as the global prevalence of metabolic syndrome continues to rise from poor lifestyle and dietary habits [117]. Exposure to these risk factors may induce epigenetic changes that lead to oncogenic transformation and carcinogenesis, potentially revealing further carcinogenic mechanisms that may be targetable.

Chronic infection by HBV/HCV is a well-established risk factor for HCC, notably by inducing genomic instability and recently demonstrating capabilities to introduce epigenetic aberrancies. HBV was found to be able to integrate its DNA into the MLL family of genes, causing loss-of-function mutations [118]. The MLL proteins are important co-activators for H3K4me3 expression, facilitating the expression of p53-mediated genes to protect against carcinogenic DNA damage [119]. Silencing of the MLL genes could lead to the loss of H3K4me3-mediated protective mechanisms against HCC. Additionally, the HBV X protein (HBx) was found to upregulate the expression of DNMTs that hypermethylated and silenced tumor suppressor genes such as IGFBP-3, RASSF1A, GSTP1, and CDKN2B, which could have contributed to tumorigenesis [16]. Similarly, chronic HCV infection was found to be responsible for epigenetic aberrancies that contribute to HCC. Hamdane et al. reported global H3K27ac changes in HCV-induced HCC, which modulated the expression of genes responsible for carcinogenesis, and also correlated positively with fibrosis stage and mortality risk [17]. Altogether, chronic HBV/HCV infections could induce changes to the epigenome, which may contribute to hepatocarcinogenesis, the eventual tumor phenotype, and prognostic outcomes.

MASLD is closely linked to metabolic syndrome, where abnormal metabolic states such as hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and hypertension drive the accumulation of fatty acids in hepatocytes, leading to chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, fibrosis, and eventually HCC [117].

Emerging evidence highlights the role of these metabolic disturbances in inducing epigenetic changes that perpetuate carcinogenesis, even after the metabolic environment returns to normal – a phenomenon known as “metabolic memory” [120,121,122]. For example, a study on Oryzias latipes demonstrated an early-life high-fat diet induced hepatic steatosis and epigenetic changes in metabolic genes [120]. Despite subsequent normalization of the diet, a subset of genomic loci linked to liver fibrosis and HCC exhibited irreversible epigenetic alterations [120].

Classic epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation and histone alterations, also play a significant role in MASLD-associated HCC. In MASLD patients, DNA methylation patterns progressively favored the expression of fibrogenic genes as the severity of fatty liver disease advances, emphasizing DNA methylation’s role in transitioning MASLD to HCC [123]. Moreover, another study reported an association between decreased global DNA methylation and greater disease severity in patients with MASLD and increased risk of developing HCC [124]. Additionally, in silico analyses by Herranz et al. revealed the upregulation of SMYD2, a histone methyltransferase known to promote HCC tumor growth, in MASLD [125]. Similarly, CBX1, a histone methylation reader, was found to be upregulated in MASLD, potentially contributing to carcinogenesis [125]. Further evidence from liver biopsies highlights an enrichment of H3K27ac at genes associated with metastasis, inflammatory response, and TNF-α signaling, linking histone modifications to MASLD-induced HCC progression [126].

These findings underscore the enduring nature of metabolic insults, which establish a lasting epigenetic landscape conducive to hepatocarcinogenesis. However, how metabolic signals influence the epigenetic landscape remains to be mechanistically elucidated. Early lifestyle or pharmacological interventions to prevent or mitigate metabolic dysfunction could be key strategies in breaking this epigenetic cycle, ultimately reducing the progression of MASLD and its associated risk of HCC.

Stratifying HCC by etiologies and understanding their unique molecular features are critical for crafting targeted and effective therapies. The distinct molecular characteristics of different HCC etiologies demonstrate the inefficacy of a universal treatment strategy [117]. For instance, while immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been approved for advanced HCC, treatment responses vary significantly depending on the underlying etiology [127]. Patients with viral-induced HCC (e.g., HBV or HCV) exhibit superior overall survival rates with ICIs compared to those with non-viral HCC, such as MASLD [127]. This discrepancy may stem from the aberrant T-cell activation in MASLD, which exacerbates tissue damage and impairs immune surveillance, ultimately diminishing the efficacy of immunotherapy [127].

Similarly, focusing on etiology-specific epigenetic traits may potentially advance the development of targeted therapies. Some promising results supporting this approach are demonstrated by the successful reduction of tumor burden in murine models of MASLD-induced HCC using bromodomain-4 inhibitors [126]. At the molecular level, these inhibitors target bromodomain-containing proteins involved in histone methylation and acetylation [128], reversing aberrant epigenetic-mediated cellular processes tied to MASLD-induced HCC, which include modulation of pathways linked to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), inflammation, and the restoration of pathways involved in bile acid, fatty acid, and xenobiotic metabolism. Likewise, inhibiting protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (PRMT5) in cell cultures and biopsies from HBV-induced HCC has shown effectiveness in reducing the dimethylation of arginine 3 on histone H4 of the covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) minichromosome. This alteration leads to the suppression of HBV RNA transcription, thereby hindering HBV replication within the host [129]. These findings illuminate the potential for identifying and targeting specific mechanisms inherent to different HCC etiologies, which could be pivotal in enhancing personalized treatment approaches for HCC.

Role of Epigenetics Biomarkers in HCC

Early diagnosis of HCC is critical as it can be potentially curative with surgery, ablation, or liver transplantation. Surveillance of high-risk patients presently involves liver ultrasonography and may include serum AFP [2]. Nonetheless, ultrasonography has limited sensitivity in detecting HCC [130]. The utility of AFP is also contentious, as the biological relationship between HCC and AFP is not entirely understood [131]. Moreover, AFP is a non-specific and poorly sensitive biomarker in detecting HCC [131]. Identifying more sensitive and specific biomarkers with a strong biological basis in HCC is important for reliable diagnosis of early HCC.

Additionally, there is a pressing need for minimally invasive strategies of diagnosis and monitoring of treatment response in HCC to address the limitations of traditional surgical tissue biopsies, which are often invasive, risky, and unsuitable for repeated sampling. Liquid biopsy has emerged as a transformative modality in this context, offering a reliable, less invasive alternative for early detection and real-time monitoring of treatment response in advanced HCC [132].

DNA methylation as biomarkers for early diagnosis and prognosis in HCC

DNA methylation markers in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) represent a promising frontier in HCC detection, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring. Tumor necrosis and apoptosis release ctDNA into the bloodstream, which can be analyzed from biospecimens containing cell-free DNA (cfDNA) for specific methylation patterns associated with HCC [133]. Advances in whole-genome bisulfite sequencing have enabled genome-wide detection of DNA methylation levels, identifying epigenetic changes that closely correlate with tumor biology [134].

The utility of DNA methylation markers in circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is rapidly emerging as a transformative approach for HCC detection, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring. For instance, Xu et al. identified 18 HCC-specific methylation markers that strongly correlate with plasma ctDNA, demonstrating their potential for early detection and prognostic evaluation [135]. Building on this, Deng et al. developed the No End-repair Enzymatic Methyl-seq (NEEM-seq) method combined with a neural network model, achieving unprecedented accuracy in detecting HCC-specific methylation patterns in cfDNA [136]. Similarly, Kim et al. introduced a cfDNA methylation assay targeting RNF135 and LDHB. When combined with serum AFP testing, this assay significantly improved sensitivity for HCC detection compared to AFP alone [137]. Adding further depth to this field, emerging evidence now supports integrating 5hmC signatures with 5mC profiling [138] for more comprehensive early diagnosis and recurrence detection in HCC [139]. Finally, Zhu et al. provided a comprehensive review of methylated ctDNA, highlighting the potential of methylated ctDNA in augmenting liquid biopsy-based approaches to not only detect HCC and predict its prognosis but also possibly monitor treatment responses [140].

Beyond detection, methylated ctDNA markers offer insights into HCC stratification and prognosis. Guo et al. identified 20 ctDNA methylation markers with high sensitivity and specificity for early-stage HCC, providing critical prognostic information [141]. Fu et al. expanded on these findings by reviewing distinct DNA methylation profiles associated with different HCC etiologies, such as viral hepatitis B or C and non-viral causes, underscoring the potential of methylated ctDNA to refine diagnostic accuracy and inform tailored treatment approaches [142].

These advances highlight the transformative potential of ctDNA methylation markers in HCC. By enabling non-invasive, highly specific, and clinically actionable insights into HCC biology, these tools hold promise in improving early detection, risk stratification, and personalized therapy in HCC.

miRNAs as biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and monitoring treatment response in HCC

Circulating miRNAs have emerged as a potential biomarker for the early diagnosis of HCC. A panel of seven unique miRNA markers (miR-29a, miR-29c, miR-133a, miR-143, miR-145, miR-192, and miR-505) were found to have a higher accuracy than AFP at a cutoff of 20 ng/ml in the detection of early-stage HCC (area-under-the-receiver-operating characteristic-curve 0.824 [95%CI: 0.781–0.868] vs. 0.754 [95%CI: 0.702–0.806], p = 0.015) [143]. Furthermore, a whole miRNome profiling study comparing HCC and non-HCC patients revealed four miRNAs (miR-1972, miR-193a-5p, miR-214-3p, and miR-365a-3p) which can differentiate HCC specifically from non-HCC patients [144]. Notably, the ongoing ELEGANCE cohort study (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT04965259) aims to validate a panel of circulating miRNA biomarkers for developing an in-vitro diagnostic kit to detect early HCC in high-risk patients. These studies highlight the potential of circulating miRNAs to surpass current diagnostic measures by providing higher accuracy in early HCC detection and greater specificity in differentiating HCC from other tumors.

Beyond early diagnosis of HCC, circulating miRNAs are increasingly recognized for their prognostic value. Certain epigenetic alterations dysregulate gene expression, leading to aggressive tumor phenotypes and generally poorer outcomes. For example, specific plasma miRNAs – including miR-410, miR-382-5p, miR-139-5p, miR-128, miR-101-3p, and miR-424-5p – are significantly correlated with critical clinical outcomes such as OS, tumor dimensions, invasion depth, multifocality, presence of viral infection, and AFP levels [144]. Further analyses across multiple databases identified 23 miRNAs capable of predicting HCC stages, with seven miRNAs (miR-550a, miR-574, miR-424, let-7i, miR-549, miR-518b, miR-512-5p) closely linked to OS [145]. Collectively, these findings suggest that miRNAs hold substantial promise for enhancing prognostic assessments in HCC.

Additionally, circulating miRNAs have garnered significant attention as non-invasive biomarkers for predicting treatment response in advanced HCC. Notably, several miRNAs have been implicated in resistance to sorafenib, a tyrosine-kinase inhibitor for advanced HCC. For instance, miR-221 promotes sorafenib resistance by inhibiting caspase-3-mediated apoptosis, thereby impairing the drug’s pro-apoptotic effects [146]. Similarly, the overexpression of miR-216a/217 contributes to resistance through the activation of the PI3K-Akt and TGF-β signaling pathways, which are key drivers of survival and proliferation in HCC [147]. Adding to this body of evidence, a recent pivotal study identified circulating miR-518d-5p as a robust predictor of poor response to sorafenib in patients with BCLC-stage C HCC and potential as a prognostic marker [148]. With further research into biomarkers measuring treatment response, clinicians may soon be able to stratify patients based on their likelihood of response to systemic treatments, enabling the optimization of therapeutic strategies and improving outcomes in this challenging disease.

Role of Epigenetic Therapy in HCC

Effective treatment for advanced unresectable HCC requires a good understanding of the molecular heterogeneity of HCC to target the key oncogenes with systemic therapies (Table 4). HCC is a heterogeneous tumor that forms on a background of various etiologies of chronic liver diseases, such as viral hepatitis, metabolic dysfunction, and excessive alcohol use, which drive different sets of oncogenes [149]. There are widely known genetic mutations responsible for the development of HCC, such as the CTNNB1 gene mutation [150], TP53 gene mutation [151], and the overexpression of the TERT gene [152]. However, no effective pharmaceutical agents exist to target these genetic mutations, leading to recent advocacies for a combinatory approach in targeting various molecular pathways implicated in HCC [153].

Epigenetic aberrations are reversible, unlike genetic mutations. As such, epigenetic-based drugs (epidrugs) targeting epigenetic marks responsible for altering genetic expressions leading to carcinogenesis have garnered vast interest. DNMT and HDAC inhibitors were the epidrugs that were the most widely studied and the first few to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating hematological malignancies [154,155,156]. These drugs were also studied in HCC in clinical trials, which will be discussed subsequently [157,158,159]. Other potential epidrugs to be discussed include histone methyltransferase (HMT) inhibitors, curaxins, and RNA-based therapies (Table 5). Finally, the emerging combinatorial therapy of epigenetic and immunotherapies is also discussed.

DNA Methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors in HCC

There are two generations of DNMT inhibitors. The first generation of DNMT inhibitors includes 5-azacytidine (azacytidine) and 5-azacytidine-2’-deoxycytidine (decitabine). Guadecitabine (SGI-110) is a notable example of a second-generation DNMT inhibitor.

Metabolites of DNMT inhibitors form irreversible adducts with DNMTs to inhibit their enzymatic activity, resulting in the hypomethylation of DNA [160]. In HCC, there is often hypermethylation and silencing of tumor suppressor genes. DNMT inhibitors could demethylate these genes to upregulate tumor suppressor gene expression [161].

Studies on first-generation DNMTs have shown significant potential in treating HCC. For example, pre-treatment with azacytidine before initiating sorafenib demonstrates improved cytotoxicity on HCC cells [162]. Additionally, a Phase I/II clinical trial of low-dose decitabine in patients with advanced HCC prolongs PFS and OS [157]. These findings suggest promising avenues for first-generation DNMTs in mitigating HCC tumorigenicity and improving patient outcomes.

SGI-110, a second-generation DNMT inhibitor with enhanced stability, could prevent HCC proliferation and enhance the cytotoxic effects of oxaliplatin. In studies involving HCC cell lines and mouse models, pre-treatment with SGI-110 before oxaliplatin administration significantly enhanced the suppression of HCC cell proliferation [163]. Beyond its role as a DNMT inhibitor, SGI-110 also acts as a PRC2 inhibitor, which disrupts the methylation of H3K27, thereby increasing chromatin accessibility and activating various tumor suppressor genes [164]. Consequently, SGI-110’s dual inhibition of DNMT and PRC2 facilitates the upregulation of tumor suppressor genes that are typically suppressed in HCC.

Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in HCC

HDAC inhibitors are categorized into four broad classes according to their chemical structures: hydroxamates, short-chain fatty acids, benzamides, and cyclic peptides. The most widely studied class is hydroxamates [165].

Hydroxamate HDAC inhibitors (e.g., resminostat, panobinostat, suberanilohydroxamic acid [SAHA]) could inhibit proliferation, induce apoptosis, and sensitize HCC cells to sorafenib. Resminostat activates apoptosis in HCC by targeting the mitochondrial-permeability-transition-pore-pathway (mPTP) [166]. It is the only drug in this class that has been tested under a phase I/II clinical trial (SHELTER study), which found that resminostat as a single agent or combined with sorafenib is safe and efficacious [158]. The combination of resminostat and sorafenib suppresses platelet-mediated HCC tumorigenesis and metastasis by suppressing the expression of CD44, epithelial, and mesenchymal genes and downregulating the mitogenic MEK-ERK signaling pathway [167]. Conjointly, panobinostat inhibits HCC proliferation by cell-cycle arrest at the G1-phase from the upregulation of the p21 (CIP1/WAF1) protein, reduces angiogenesis, and induces apoptosis via the caspase-12 pathway [168]. Moreover, panobinostat potentiates the cytotoxic effects of sorafenib and decreases tumor size, which prolongs survival in mice [169]. Lastly, SAHA induces apoptosis by reducing the expression of the Notch and Raf pathways [170] and synergistically enhances the cytotoxic effects of sorafenib by the inhibition of autophagy [171]. Altogether, hydroxamate HDAC inhibitors potentially promote apoptosis and boost the cytotoxic effect of sorafenib in HCC.

Other classes of HDAC inhibitors also demonstrate the ability to inhibit the growth of HCC cells. Valproic acid, a short-chain-fatty-acid HDAC inhibitor, downregulates the Notch-1 signaling and activates caspase-3 activity, resulting in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [172]. Additionally, valproic acid is shown to overcome drug resistance against sorafenib in HCC by downregulating the Jagged-2-mediated Notch1 signaling and the EMT-related proteins [173]. In a phase II clinical trial, a combination of valproic acid and hydralazine with gemcitabine and cisplatin, followed by doxorubicin and dacarbazine, demonstrated safety and survival benefits in advanced HCC patients [159]. Furthermore, chidamide, a benzamide HDAC inhibitor, upregulates p21 mRNA expression and induces apoptosis in HCC cells [174]. Finally, romidepsin, a cyclic peptide, activates the Erk/cdc25C/cdc2/cyclin-B and JNK/c-Jun/caspase3 pathways to trigger G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, respectively, in HCC cells. Romidepsin was also found to reduce HCC tumor size in vivo significantly [175]. Thus, various HDAC inhibitors offer a multifaceted approach against HCC development by cell-cycle arrest and inducing apoptosis. Nonetheless, human trials on these classes of HDAC inhibitors are needed to evaluate their potential safety and efficacy clinically.

There is a growing interest in the next generation of HDAC inhibitors for HCC, underscored by promising preliminary results. Among these, CXD101, a selective inhibitor targeting class I HDACs (HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3), has demonstrated favorable safety profiles in a Phase-I trial involving patients with advanced cancers [176].

Histone Methyltransferase (HMT) and Lysine-Specific Histone Demethylase (KDM) Inhibitors in HCC

The inhibition of histone methyltransferases (HMTs) and lysine-specific histone demethylases (KDMs) represents a promising epigenetic therapeutic strategy in HCC. Several HMT inhibitors have already advanced to clinical trials, with tazemetostat being the most notable example [177]. This FDA-approved EZH2 inhibitor has shown efficacy in advanced epithelioid sarcoma and follicular lymphoma and has demonstrated anti-tumor activity in HCC by inhibiting CD13 and β-catenin expression, thus curtailing tumor development and progression [178]. Similarly, pinometostat, a DOT1L inhibitor currently in Phase I trials for MLL-rearranged leukemia [179], has shown potential in HCC by upregulating E-cadherin and downregulating Snai1 and VIM, thereby attenuating EMT and reducing invasiveness [180]. While promising, further studies are necessary to elucidate the full molecular mechanisms and clinical efficacy of these agents in HCC.

Preclinical studies have identified additional HMT inhibitors with specific anti-HCC activities. For instance, UNC0379 inhibits SET8 and blocks H4K20 methylation, downregulating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway while activating p53 signaling to suppress tumor proliferation and enhance chemosensitivity to docetaxel [63]. Similarly, UNC0638 inhibits G9a-mediated H3K9 methylation, leading to upregulation of the tumor suppressor Bcl-G and promoting p53-dependent apoptosis in liver cells with DNA damage [62]. CM-272, a dual G9a and DNMT1 inhibitor, restores FBP1 expression, disrupts HCC’s metabolic adaptation to hypoxia, and reduces proliferation [76]. Another promising compound, UNC1999, targets both EZH1 and EZH2 to reduce H3K27me3 at the SLFN11 promoter, thereby sensitizing HCC cells to sorafenib and enhancing anti-tumor effects [56]. Similarly, GSK343, another EZH2 inhibitor, induces autophagic cytotoxicity and improves the response of HCC cells to sorafenib [181]. Collectively, these HMT inhibitors demonstrate significant potential in restricting HCC growth, mitigating chemoresistance, and targeting key oncogenic pathways.

Conversely, KDM inhibitors leverage the induction of histone methylation to combat HCC progression. KDM1A demethylates H3K4 at the promoters of Prickle1 and APC, silencing these tumor-suppressor genes and driving the β-catenin pathway, which promotes stemness and chemoresistance [65]. KDM1A also demethylates H3K4me1/2 at the promoter of GADD45B, suppressing its apoptotic function and enhancing tumor survival [182]. Inhibitors such as ZY0511 specifically target KDM1A activity, showing robust anti-proliferative effects in vitro and in vivo [182]. Similarly, ML324, a selective inhibitor of KDM4, which primarily demethylates histone H3 lysine 9 me2/me3 [183], induces apoptosis in HCC by activating the ATF3-CHOP-DR5 pathway and increasing the expression of BIM [184]. These KDM inhibitors not only disrupt oncogenic pathways but also restore apoptotic mechanisms, offering dual anti-tumor effects in HCC.

The emergence of HMT and KDM inhibitors underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting epigenetic regulators in HCC. These compounds, by addressing both tumor growth and chemoresistance, represent a promising direction for the development of precision therapies in HCC.

Curaxins in HCC

Curaxins (e.g., CBL0137) is a novel anti-cancer drug class targeting the genome’s spatial organization. Unlike conventional DNA-intercalating chemotherapeutic agents, curaxins could intercalate into the DNA without notable DNA damage to increase the rigidity and modify the 3D conformation of chromatin, which inhibits enhancer-promoter communication of oncogenes [185]. Also, curaxins could inhibit the Facilitates Chromatin Transcription (FACT) complex, a histone chaperone regulating nucleosome stability and chromatin remodeling during transcription [186]. Inhibition of FACT has anti-cancer properties by activating p53 and suppressing NF-κB expression [187].

The FACT complex was found to be upregulated in HCC and contributed to HCC progression. Under oxidative stress, FACT expression is upregulated via the NRF2-KEAP1 pathway in HCC, driving NRF2 expression to increase antioxidative gene expression counteractively. Curaxin CBL0137, which is shown to be selectively effective against HCC cells in inhibiting FACT, can greatly reduce tumor size and potentiate the oxidative stress of sorafenib against HCC in vivo [188].

RNA-based therapies in HCC

In HCC, oncogenic miRNAs are upregulated, while tumor-suppressive miRNAs are downregulated. As such, inhibiting oncogenic miRNAs and replacing tumor-suppressive miRNAs present opportunities to treat HCC. For instance, the introduction of anti-miR-221 in transgenic mice, which overexpress the oncogene miR-221, significantly reduced the quantity and volume of the HCC tumor [189]. Conversely, miR-122 is a tumor-suppressive miRNA and is often depleted in HCC. Reintroduction of miR-122 into an orthotopic HCC model reduces HCC development, invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis [190]. Furthermore, miR-122 is an important factor for HCV proliferation, a risk factor for HCC. In a Phase-I trial, patients with HCV were randomized to receive a single 2 mg/kg dose of RG-101, a next-generation conjugated anti-miR-122 inhibitor, which demonstrated good safety and significant HCV load reduction within four weeks [191]. Herein, tumor-suppressive miRNA replacement and inhibition of oncogenic miRNA demonstrate some early promise in inhibiting the development and progression of HCC.

Potential combination of epigenetic therapies with immunotherapies in HCC

The intersection of epigenetic therapy and immunotherapy represents a transformative approach to overcoming the limitations of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in HCC. While ICIs targeting PD1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 have revolutionized cancer therapy, their efficacy remains confined to a subset of patients [192], emphasizing the need for combinatorial approaches to overcome both intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms. Epigenetic modifications play a critical role in shaping tumor immunogenicity, regulating immune cell functionality, and modifying the tumor microenvironment (TME) [193], making them ideal candidates to complement and enhance the efficacy of ICIs in HCC. Key principles underlying this therapeutic synergy will be outlined, with additional insights available in other studies [194, 195].

Mechanisms of synergy between epigenetic and immunotherapy

Epigenetic therapies synergize with ICIs by modulating the immunosuppressive TME and improving immune cell infiltration in HCC. The HCC TME, dominated by tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and regulatory T cells (Tregs), is a major contributor to immune evasion [196]. Epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation and histone alterations, suppress key genes essential for T-cell trafficking and activation, as well as perpetuating immune tolerance [195]. Epigenetic agents such as DNMT inhibitors, HDAC inhibitors, and HMT inhibitors counteract these effects by reactivating chemokines and cytokines, thereby enhancing immune infiltration and restoring immune sensitivity in HCC [196].

Potential clinical and preclinical efficacies of combinatorial epigenetic and immunotherapy

Recent studies highlight the transformative potential of combining epigenetic therapies with ICIs in HCC. For instance, HDAC8 inhibitors have demonstrated the ability to enhance the efficacy of anti-PD-L1 therapies [52]. In preclinical HCC models, selective HDAC8 inhibition reactivated chemokine production and promoted T-cell infiltration into tumors, effectively relieving T-cell exclusion. This combination resulted in sustained tumor suppression, driven by T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and induced robust memory T-cell responses, providing long-term immunity against tumor rechallenge [52].

Similarly, HDAC6 inhibitors have shown promise in sensitizing advanced HCC to ICIs. By reprogramming immune cells and increasing the expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells, HDAC6 inhibition enhances the antitumor activity of CD8 + T cells and amplifies immune responses, creating a more favorable tumor microenvironment [197].

Additionally, a selective class-I HDAC inhibitor, CX101, has been demonstrated to improve the treatment response of anti-PD1 inhibitors against HCC with high HDAC1/2/3 expression [198]. Mechanistically, CX101 restores the previously deficient interferon-γ/STAT1 signaling pathway, thereby promoting the recruitment of cytotoxic T-cells and increasing the expression of Gasdermin-E to induce tumor pyroptosis [198]. Building on this, a Phase-II clinical trial among HCC patients is actively being conducted to evaluate the efficacy of CXD101 in combination with the anti-PD1 inhibitor, geptanolimab, in relation to established treatments (lenvatinib or sorafenib) (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05873244). These strategic explorations highlight the progressive steps being taken to refine oncological treatment paradigms through combination therapies.

Emerging epigenetic targets show significant promise in modulating immune responses and hold potential candidates for combination therapies with ICIs to enhance treatment efficacy in HCC. One prospective target is KDM1A, whose inhibition amplifies T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity against HCC in vivo [199]. This effect is mediated through the upregulation of PD-L1 expression, which enhances the recruitment and activation of antitumor immune responses [199]. In addition, EZH2 inhibitors have exhibited the ability to modulate both innate and adaptive immunity. These inhibitors reprogram intra-tumoral regulatory T cells (Tregs), facilitating the recruitment of effector CD8+ and CD4 + T cells to combat HCC in vivo [200]. Beyond T-cell modulation, EZH2 inhibition also enhances the cytotoxic activity of natural killer (NK) cells by upregulating activating ligands, such as NKG2D ligands, thereby bolstering innate immune responses against the tumor [201]. Moreover, DNMT inhibitors act by upregulating endogenous retroviruses, reactivating silenced immune pathways, and enhancing the immunogenicity of tumor cells [164]. These findings highlight the potential of targeting epigenetic mechanisms, including KDM1A, EZH2, and DNA methylation, in combination with ICIs to overcome immune resistance and achieve more robust and durable antitumor responses.

Epigenetic biomarkers in predicting response to immunotherapy

Epigenetic biomarkers have the potential to significantly enhance the prediction of response to immunotherapy by identifying key immunomodulatory signatures that influence treatment outcomes [193]. DNA methylation-based deconvolution analysis has uncovered specific DNA methylation patterns that drive immunosuppression, even in tumors initially classified as “hot” due to higher cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) infiltration levels [202]. These suppressive signatures can hinder the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade by promoting immune evasion.

Notably, the expression of EZH2 and DNMT1 in tumors has been shown to repress the production of T-helper 1 type chemokines, such as CXCL9 and CXCL10, which are crucial for recruiting CD8 + T cells into the TME [203]. This repression correlates with reduced infiltration of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and poorer clinical outcomes [203]. Moreover, EZH2-driven epigenetic modifications can directly suppress the expression of PD-L1 by increasing H3K27me3 levels at the promoters of CD274 and IRF1 in HCC tissues [204]. This mechanism further impairs immune recognition and contributes to immune resistance.

Given the complex interplay of factors influencing immunotherapy responses – ranging from immune checkpoint expression [205] and genetic mutations [206] to the cellular composition of the TME [207] – there is a critical need for integrative approaches to patient stratification. Combining epigenetic biomarkers with advanced predictive algorithms that incorporate multi-omics data and spatial profiling of the TME [208] could significantly improve the sensitivity and accuracy of response predictions. Additionally, integrating liquid biopsy analyses may offer a minimally invasive method to capture dynamic changes in tumor biology [209]. Such comprehensive approaches refine patient selection for immunotherapy and identify opportunities to incorporate epigenetic therapies as adjuncts, thereby enhancing treatment efficacy and overcoming resistance.

Conclusions

This review presents the epigenetic aberrancies in HCC, notably in DNA methylation, post-translational histone modifications, alteration to the 3D conformation of the genome, and RNA regulations. We also discuss the importance of considering etiology-specific epigenetic mechanisms for more efficacious targeted treatment of HCC of different etiologies. Finally, we highlight the promise of using the epigenetic biomarkers for HCC and potentially as targets for anti-cancer therapy.

While the field of cancer epigenetics is developing rapidly, there are several limitations to its application in clinical practice. A key challenge lies in the lack of robust and validated predictive biomarkers for HCC, especially for measuring treatment response to systemic therapies in advanced stages of the disease. Although circulating biomarkers such as circulating tumor cells [210], circulating DNA [211], and extracellular vesicles [212] show promise, studies focusing specifically on epigenetic-based circulating biomarkers remain limited [213], except for some miRNAs [146,147,148]. This gap is particularly critical given the intimate role of epigenetic mechanisms in HCC pathogenesis and progression. Developing reliable, non-invasive epigenetic biomarkers could complement critical insights into disease monitoring and therapeutic response.

Additionally, while epidrugs targeting epigenetic modifications hold immense therapeutic potential, they are often associated with elusive and unpredictable side effect profiles. Many epidrugs exert genome-wide effects, leading to off-target consequences that are not always specific to the tumor, raising concerns about their safety [214]. Compounding this issue, the limited number of clinical studies validating the safety and efficacy of epidrugs in HCC patients further restricts their integration into routine practice. Addressing these challenges through rigorous biomarker validation and comprehensive clinical trials will be essential to fully harness the transformative potential of epigenetics in HCC diagnosis and treatment.

Nonetheless, the epigenetics of HCC remain exciting to explore as they potentially open doors to novel preventive measures and treatments. Growing evidence points to epigenetically-driven carcinogenesis, which should be detected early and targeted [11,12,13]. Furthermore, HCC is an aggressive malignancy with over 60% detected at advanced stages due to present surveillance inadequacies [215]. Knowledge of the epigenetic signatures of HCC could potentially be applied to complement existing diagnostics to improve the accuracy of detecting HCC, predict response to treatment, and prognosticate patients. Furthermore, epidrugs have demonstrated capabilities to work synergistically with existing anti-tumor agents against HCC and even reverse resistance against these agents [56, 63, 158, 162, 163, 169, 171, 173, 180, 181, 188]. As HCC has wide tumor microenvironmental and systemic epigenetic changes [87], epidrugs may create a more supportive cellular environment for anti-tumor agents to work effectively against HCC [216]. Additionally, in the current landscape where epidrugs have been approved by the FDA for other malignancies [154,155,156], epidrugs remain a promising adjunct in addition to other combination therapies for personalized treatment against HCC. With further validation in clinical cohorts, knowledge of the epigenetics of HCC can potentially be translated to develop useful clinical biomarkers and treatment targets.

Responses