The essential role of cement-based materials in a radioactive waste repository

Introduction

Cement-based materials find widespread application in deep geological repositories designed for spent fuel (SF), high-level radioactive waste (HLW), and low-/intermediate-level radioactive waste (L/ILW)1,2,3. Conceptually, these repositories comprise both engineered and natural barriers, each serving specific safety functions that collectively ensure the overall safety of the repository system4. The critical components and environmental conditions for these repository concepts are carefully assessed to fulfill safety functions, and the roles of distinct cementitious materials vary based on both waste types and geological considerations. Generally, a cement-based tunnel support provides mechanical stability that is important during the operational phase, and in the long term, it should minimize tunnel deformation in combination with suitable backfill materials. Cementitious materials might act as hydraulic and transport barriers, and most importantly they are designed to provide a chemical environment that minimizes steel corrosion, slows down degradation of wastes, and therefore slows down the release and transport of radionuclides. Service lives of cement-based materials may be very different, depending on their functionality. For example, a cementitious tunnel support may be needed only during construction and operation of a repository, while cement-based materials that are considered as barrier for radionuclide retention and contribute to the chemical environment might need to keep their properties/functionality for very long time.

Across many specific repository concepts that exist worldwide, a generic multi-barrier system is consistently employed. Notable examples where considerable amounts of cement would be used mainly include: 1) HLW disposal cell in granite5; 2) HLW disposal cell in clay; 3) L/ILW disposal cell in granite; and 4) L/ILW disposal cell in clay6. Cement plays a pivotal role in most repository design concepts. In addition, near surface-disposal for (very) LLW and ILW in engineered structures is conducted in various countries7, and in these systems cement based materials that are used in conditioning and packaging of the waste, and in the structures themselves, also play an important role and their properties have to be guaranteed up to their target service life8.

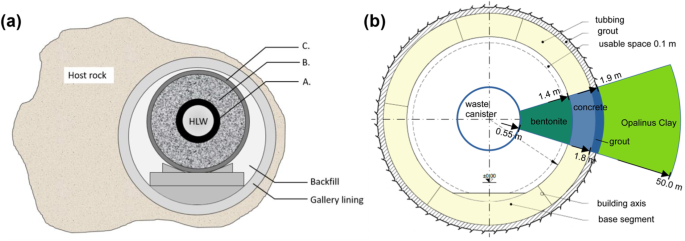

The strategy of high-level radioactive waste (HLW) disposal in clay has been embraced by countries such as Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. In Belgium, for example, Fig. 1a offers a conceptual representation for disposal of HLW in Boom Clay, a plastic argillaceous formation9,10. In the Belgian concept the cement overpack and the concrete maintain a high pH during and well beyond the thermal phase (caused by the heat generation from beta and gamma emitting fission products) to passivate the carbon steel overpack, which is intended to limit corrosion and radionuclide release.

a Cross-section of the “supercontainer” reference concept with its main components: A. carbon steel liner (overpack), B. concrete reinforcement (buffer) and C. envelope liner9. b Diagram showing the cross section of the HLW near-field configuration within the Opalinus clay host rock. The proportions of the host rock are not accurately represented in comparison to the near-field materials.

Figure 1b delineates the elements of the Swiss concept of an HLW tunnel embedded in Opalinus Clay, serving as the host rock11. In the Swiss case, the space between the steel canister and the concrete tunnel support (tubbing) surface is filled with compacted bentonite blocks, while the annular gap between the tubbing and the clay host rock is addressed with a rapidly setting grout according to the current concept. The tunnel support is only needed during operational phase. The long-term barrier is the bentonite backfill (buffer), which suppresses liquid flow due to its low permeability, strongly retards transport of most radionuclides due to its sorption properties and prevents tunnel convergence (i.e., the inward movement or deformation of tunnel walls after excavation) because of swelling pressure buildup after water saturation.

In the French concept12, the annular gap between a carbon steel sleeve (liner) and the host rock is filled with a bentonite/cement grout, establishing a corrosion-limiting environment specifically during the thermal phase. The moderate alkalinity of the grout (pH ~11) is expected to be promptly neutralized thereafter, to prevent dissolution of the wasteform glass under alkaline pH conditions, and consequent increased rate of radionuclide release.

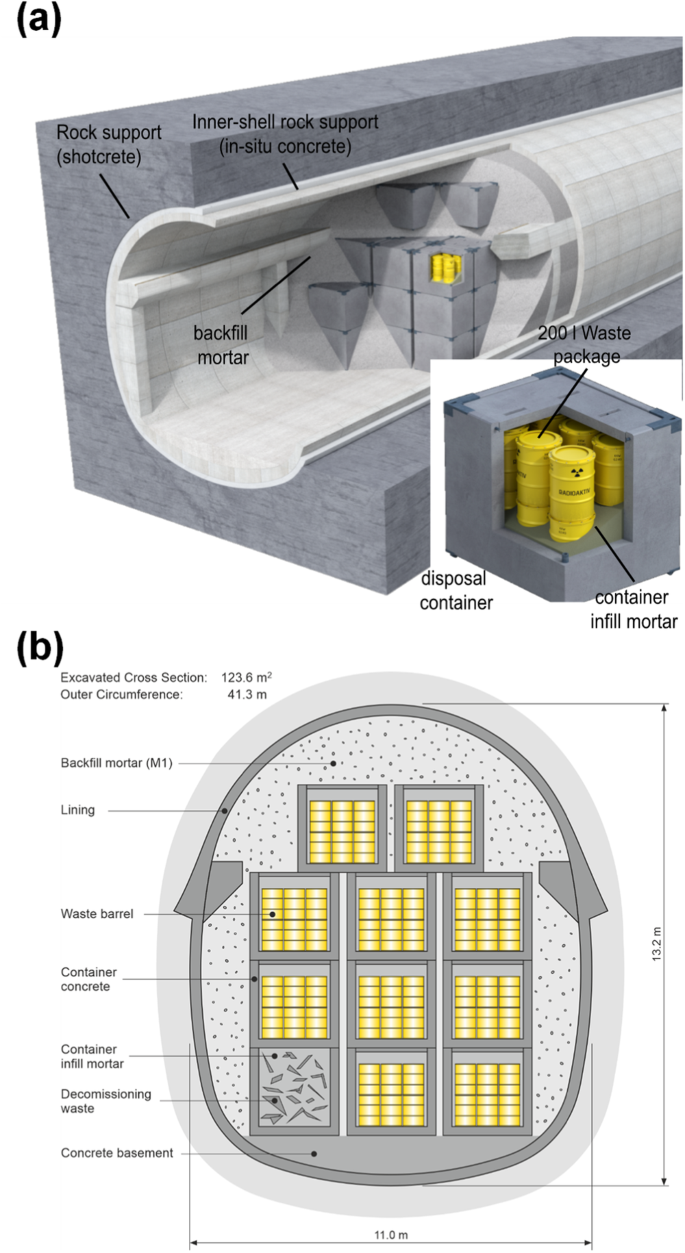

A L/ILW repository is characterized by substantial waste volumes with lower radiotoxicity and low heat generation, but can exhibit significant variability and heterogeneity in physicochemical properties13. Deep geological repositories for L/ILW will generally use large quantities of cement-based materials (concrete, mortar) used for waste conditioning, tunnel support (shotcrete), and cavity backfill. These materials may have diverse recipes, varying in Portland cement (PC) content, supplementary cementitious materials, and aggregates, which influence mechanical and transport properties considerably14,15,16. Figure 2 illustrates the Swiss concept for L/ILW disposal in clay. During the emplacement phase, waste drums are intended to be enclosed in concrete containers, with the void space between drums backfilled using low-viscosity mortar. These containers are to be secured in caverns, and a specially designed mortar is applied to fill the remaining cavities. Shotcrete liners and reinforced in-situ concrete are to be employed for tunnel and cavern construction. While the aggregates to be used in the concretes and mortars are predominantly siliceous (primarily quartz), calcareous materials (limestone) could also be considered. In summary, the backfilled caverns will contain radioactive waste, hydrated cements, significant quantities of steel (drums, tunnel support, and construction materials), and aggregates. This defined multibarrier system (waste matrix, containers, backfill material) is also prevalent in concepts considering plastic clays, as seen in approaches put forward by Belgium and the Netherlands6. Particularly, spatio-temporal cement material evolution in L/ILW repositories situated in low permeability clay host rock might be controlled by local conditions of water saturation. Water availability in the bottom section of the cavern thus has a local impact on cement degradation (porewater pH), which in turn control various (bio-)chemical processes that back-couple to the saturation and degradation state, either in terms of water and gas transport properties (diffusivity, porosity), or in change of local chemical conditions, or in form of sources or sinks for gas and water17.

a Representation of a reference design for an emplacement cavern for L/ILW disposal in Switzerland17. b Cross section of a possible L/ILW emplacement tunnel15.

For L/ILW disposal in granite, similar cement based multibarrier systems to those which will be employed for L/ILW disposal in clay are also utilized18,19. The water inflow is much faster, and any generated gases that are not consumed in the cement near-field (e.g. CO2) can easily escape via fracture zones of granitic rock. A significant water de-saturation like in the clay-based repository would not be expected18.

In general, the anticipated service life of the cement barriers for radioactive waste disposal, specifically for radionuclide retention, is up to several tens of thousands of years (although the defined period varies for different countries)20, far surpassing the typical lifespan of conventional concrete structures. This extended duration necessitates a comprehensive assessment of the long-term evolution of cement-based materials, encompassing considerations of material performance, chemical stability/degradation in the potential presence of groundwater, and interactions with surrounding minerals3.

Concerns regarding the potential for highly alkaline near-field conditions from cement use led to the development of “low-alkali” or “low-pH” cements, such as ESDRED and LAC. These cements, formulated with reduced PC content and supplemented with fly ash/slag and/or reactive silica, are undergoing long-term testing with host rocks like claystone21,22,23. A detailed study of the aged cement-clay interaction zone at the Mont Terri rock laboratory, examining samples aged 2.2 and 4.9 years, revealed minimal reaction in claystone for both standard PC (initial pH >13.5) and low-pH cements23. This indicates that replacing PC with low-pH cement to limit reaction extent between claystone and cement is neither advantageous nor necessary. Moreover, using low-alkali cements introduces uncertainties due to higher organic additive content and the less established engineering performance of these newer materials.

To reduce the carbon footprint of the repository construction and operation, other blended cements, e.g., LC3 (Limestone Calcined Clay Cement)24 or CEM II/B-LL25 are under consideration to be employed. In addition, alternative cements, e.g., geopolymer, magnesium carbonate cement, magnesium silicate cement, alkali-activated cement, sulfoaluminate cement, calcium aluminate cement, phosphate cements and others, are being investigated for specific applications in waste conditioning3,26,27,28,29, pending rigorous safety evaluations. As the scientific community delves deeper into these considerations, the quest for sustainable and secure radioactive waste containment, including the use of cement-based materials, will remain a focal point in discussions on nuclear energy and waste management.

In this review, PC-based cement, renowned as the most common construction material and extensively studied for its applications in geological repositories, is the primary topic of discussion. The complex spatial and temporal geochemical evolution of a cementitious near field involves intricate processes, and research in this area places a primary focus on the degradation of cement phases and other concrete constituents, along with interactions with groundwater, wastes, host rocks, and other engineered barrier components. These multifaceted aspects constitute crucial factors influencing the overall safety of cement-rich deep geological repositories.

Cement degradation

Radioactive waste management commonly employs a three- to four-stage conceptual description to depict the degradation stages of cement phases associated with the pore water30. These stages, delineated by distinct hydrated cement phases buffering the pore water pH within specific ranges, result from sequential dissolution or transformation of cement hydrates driven by external factors such as transport of groundwater, solutes, and gaseous CO2. The key features of transport-controlled models for cement degradation encompass: i) 13.5 > pH > 12.5, alkali release (Na+ and K+); ii) pH = 12.5, portlandite dissolution; iii) 12.5 > pH > 10, calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) and aluminoferrite mineral dissolution. In the latter stages of cement degradation, the formation of carbonates, clay minerals, or zeolites induces a decline in pH to near neutral values1,30. In addition, other cement degradation processes could occur when interacting with high-concentration Cl− (e.g., from saline water), leading to the formation of Friedel’s salt (Ca4Al2Cl1.95(OH)12.05 ∙ 4H2O) at the expense of primary portlandite and calcium aluminate. Sulfate attack may also occur if dissolved sulfate is present in the surroundings (e.g., clay pore solutions), resulting in the precipitation of gypsum (CaSO4 ∙ 2H2O), ettringite (Ca6Al2(SO4)3(OH)12 ∙ 26H2O), and/or thaumasite (Ca6(Si(OH)6)2(SO4)2(CO3)2 ∙ 24H2O) by consuming the original cement phases20.

Cement-aggregate reactions

The thermodynamic instability in the very long term of (alumino-)silicate aggregates (e.g., quartz, feldspars) and carbonate aggregates (containing dolomite or siliceous limestone) embedded in a cementitious matrix is a well-documented phenomenon31,32,33. Although many of these minerals are considered “non-reactive” or “low-reactivity” aggregates when used in concretes intended for civil engineering purposes – and this is certainly justified when considering timeframes of decades to centuries – their potential reactions over millennia or more do require assessment in the context of the long-term evolution of the cementitious near field. Various aggregate-cement reaction mechanisms have been identified, including the alkali-silica reaction (ASR), and even some very slow pozzolanic reactions related to silicate aggregates. De-dolomitisation processes may be associated with dolomite occurrence in aggregates, and these reactions are often accompanied by dimensional changes, causing local stress increases, and accelerating cement degradation. Notably, in concretes with reactive aggregates, the stage of cement degradation determined by portlandite saturation might have a shorter duration than would be expected from scenarios based solely on diffusive interaction with host rock pore water, especially in (near) water-saturated conditions, due to participation of calcium provided by portlandite in reactions with the siliceous aggregates.

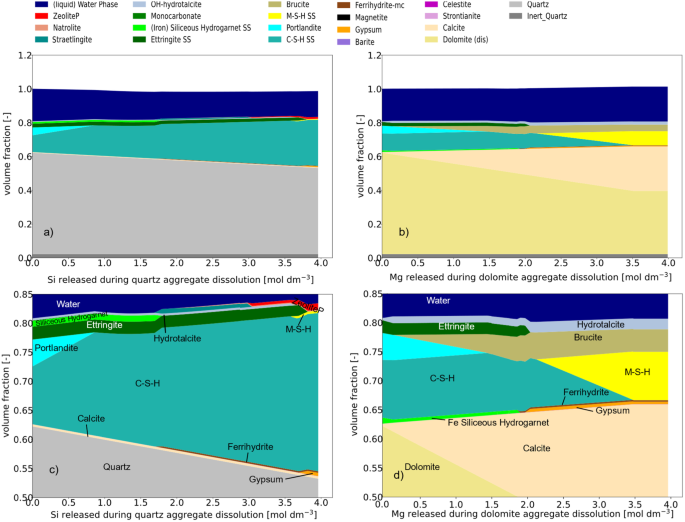

Silica (SiO2, which may be present in various forms and polymorphs) from the reactive aggregates is identified by Leemann et al.33 as a major source of reactive constituents within concretes in the long term. Reactive substances listed by Thomas et al.34 include opal, chalcedony, certain forms of quartz, cristobalite, tridymite, and various glass types, all characterized by microcrystalline or partially amorphous forms, and/or exposure to mechanical strain or thermal impact. An illustration of mineralogical changes in concrete due to silica release from quartz dissolution is provided by Kosakowski et al.15, as depicted in Fig. 3a, c. The system starts as fully hydrated concrete (0 Si released), and as Si is released, portlandite is consumed, and C-S-H is formed. If more than ~1 mol dm−3 Si is released, the C-S-H amount increases while the calcium to silica (C/S) ratio of C-S-H decreases. The reactions stop when quartz reaches equilibrium with the pore solution (at ~3.95 mol dm−3 Si released).

a, c Thermodynamic modeling example of the mineralogical evolution of a fully hydrated concrete upon the dissolution of quartz. b, d Thermodynamic modeling example of the mineralogical evolution of a concrete upon the dissolution of dolomite. Full-scale view on top and a detailed view on the bottom. Mineral phase names are provided in thermodynamic setup: Inert_Quartz – inert mineral phase with the density of quartz; SS solid solution. (adapted from ref. 15).

The term “alkali-carbonate reaction” (ACR) is also used; sometimes it refers to the reaction of amorphous silica present as a minor component in carbonate aggregates35 with alkaline pore fluids, and sometimes the calcium-magnesium carbonates, i.e., dolomite, will themselves react36,37. The alkalis in cement pore water can react with dolomite crystals in aggregates, inducing the production of brucite (Mg(OH)2) and calcite (CaCO3), as described by Eq. (1). According to Leemann et al.33, the precipitation of brucite occurs in dolomite pores without expansion. Alkalis (Na, K) and carbonate react with portlandite to form calcite in cement paste adjacent to the aggregates while recycling Na and K to the pore solution again, which represents a form of de-dolomitisation. For a reaction process with unlimited dolomite availability, all Ca is leached from the cement phases (Fig. 3b, d), and the equilibrium pH of the pore water drops below 10. As Ca from cement phases is consumed during these reactions, cement is driven toward a degradation stage dominated by C-S-H.

The temporal evolution of the internal degradation within concretes over extremely extended time periods currently remains an open issue. Particularly, effective kinetic rates for dissolution of aggregate minerals are uncertain, specifically under partially-water-saturated conditions and if combined with highly uncertain determination (or definition) of “reactive surface areas”. For cases where such aggregate-cement reactions need to be avoided or reduced, the usage of inert aggregates could be evaluated, i.e., aggregate minerals that are in thermodynamic equilibrium with cement phases. For PC based materials, the obvious choice would be pure limestone (calcium carbonate, calcite), which will react only to a limited extent until carbonate saturation of the relevant hydrous carboaluminate phases is reached, but remains stable beyond this38.

Interaction with clays

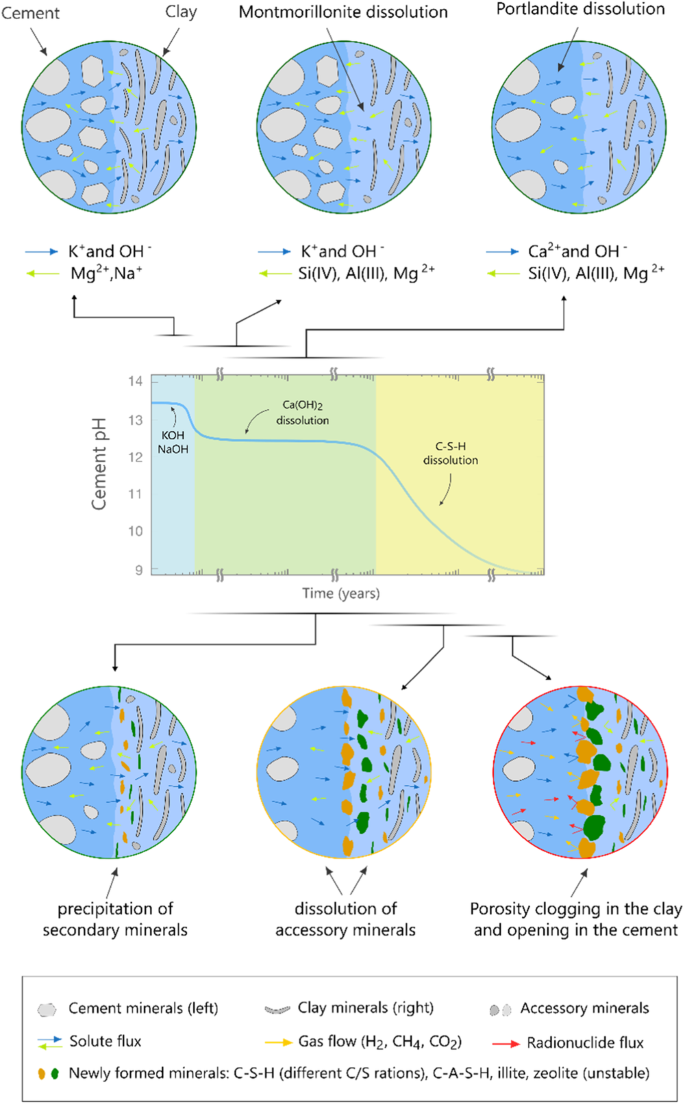

Cement and clay-based materials are commonly used as materials for the engineered barrier system, and contacts between both materials are commonly found. Such contacts include interfaces between cement-based tunnel support and clay host rocks. Cement-based and clay-based materials exhibit distinct chemical compositions that induce strong solute concentration differences at their contact. Fresh cements are characterized by high alkalinity, attributed to the presence of alkali hydroxides and portlandite. Consequently, during various stages of degradation, cementitious materials serve as substantial sources of soluble hydroxides and calcium39. In contrast, clay pore water typically maintains a near-neutral pH and possesses a higher inventory of silica, carbonates, and potentially sulfates in aqueous species, facilitating mineral-fluid interactions20,40,41. As shown in Fig. 4, the chemical disparity in the composition of cement and Opalinus Clay pore water is anticipated to induce diffusive solute fluxes and subsequent dissolution-precipitation reactions at their interfaces. These chemical interactions are expected to alter the mineralogical composition and transport properties of materials within a certain extent around the interfacial zone. Dissolution/precipitation processes within porous materials induce microstructural changes, leading to local decrease or increase of porosity. Simultaneously, the modification of pore water composition may influence surface speciation mechanisms, thereby altering the sorption capacity of host rocks and engineered barriers. Quantifying the spatial and temporal extent of these interactions is essential for evaluating the significance of these changes in relation to the safety function of host rocks and buffer materials.

Illustrative diagram depicting the degradation of cement phases along with the chemical processes involved in interacting with clay minerals (adapted from ref. 57).

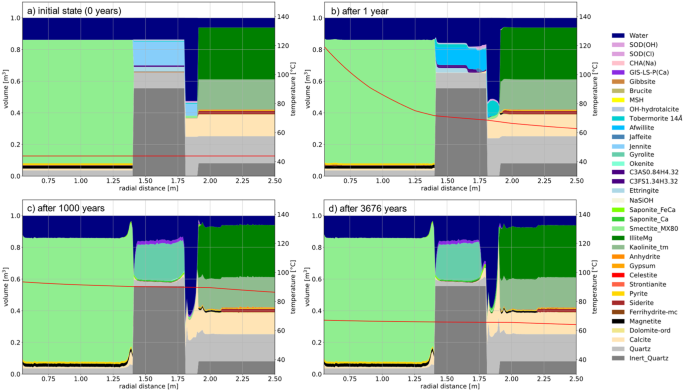

Utilizing the OpenGeoSys-GEMS coupled code42 and adopting the approach for reactive transport calculations reported in Cloet et al.43, the spatial and temporal mineralogical profiles covering the multi-barriers in HLW disposal in clay and a timespan of 0-3676 years are investigated and shown in Fig. 5. In Cloet et al.43 and in models incorporating the thermal pulse, ettringite (and AFm phases overall) will destabilize as temperature rises. Ettringite does not reform post-thermal exposure, as Opalinus Clay diffusively equalizes the elevated sulfate concentrations in cement materials following ettringite dissolution. After 1 year (Fig. 5), initial signs of cement-clay interactions emerge. As the high pH front advances into Opalinus Clay, minor dissolution of quartz and kaolinite takes place, accompanied by zeolite precipitation. The grout in contact with Opalinus Clay undergoes rapid degradation due to high diffusive solute fluxes driven by strong geochemical gradients. Calcium and hydroxyl ions from dissolution of cement phases are transported towards the Opalinus Clay, while dissolved CO2 in Opalinus Clay is transported towards the grout. In the mixing zone near the interface, a long-term accumulation of carbonates (calcite) occurs. Within less than 1000 years, the degradation front reaches the tubbing concrete (Fig. 1b), resulting in significant grout evolution and porosity increase, except at the Opalinus Clay interface, where porosity is decreased. One should remark that the grout formulation used in the calculation is a provisional formulation. Upon reaching the tubbing concrete, the leaching front slows due to increased resistance to leaching and carbonation, attributed to higher cement mineral content. The evolution at the bentonite/tubbing concrete interface is somewhat analogous to the grout/Opalinus Clay interface but less pronounced.

Temporal coverage includes intervals at 0 (a), 1 (b), 1000 (c), and 3676 years (d). Spatial coverage extends from the canister boundary (i.e., 0 m) to a radial distance of 2.5 m, progressing sequentially through the barriers of bentonite, tubbing concrete, grout, and Opalinus clay. The simulation accounts for reactive aggregates in the concrete.

The engineered barriers that may interact with cement phases in relevant repositories primarily consist of bentonite backfill materials and iron phases (e.g., steel canisters and steel reinforcement). As explained in relation to Fig. 5, the impact of bentonite backfill on the degradation of cement phases is not particularly pronounced44. Within the bentonite, minimal smectite dissolution is observed, and only small amounts of zeolite precipitate. Some calcite and quartz precipitate, leading to a notable reduction in porosity in the bentonite. On the tubbing side of the interface, concrete degradation is noted, providing silica for reactions in the bentonite. The leaching front progresses much more slowly compared to the equivalent front in the grout.

Interaction with granite

Concerning the interaction between cementitious materials and the granite host rock, alterations on the cement side are influenced by contact with groundwater in the crystalline bedrock, resulting in typical alteration phenomena in subsurface construction materials. The alkaline plume from concrete leaching affects the granite by dissolving primary silicate minerals (e.g., biotite and albite) and precipitating secondary phases (e.g., zeolite45, C-S-H46,47, calcium (alumino)silicate hydrate (C-(A)-S-H)48, calcite46, vaterite46, and titanite), potentially impacting the flow regime in the repository near field49. This process requires dissolved Ca2+ that is supplied from the dissolution of portlandite, C-S-H or ettringite, and dissolved CO2 (i.e., HCO3− and CO32−) that could be from either from contact with atmosphere (if the repository is open) or the local pore water in contact with calcite filled fractures at near neutral pH50. Generally, chemical alteration processes at the concrete/granite interface in underground repositories are anticipated to be slow18,19.

Interaction of cement with steel

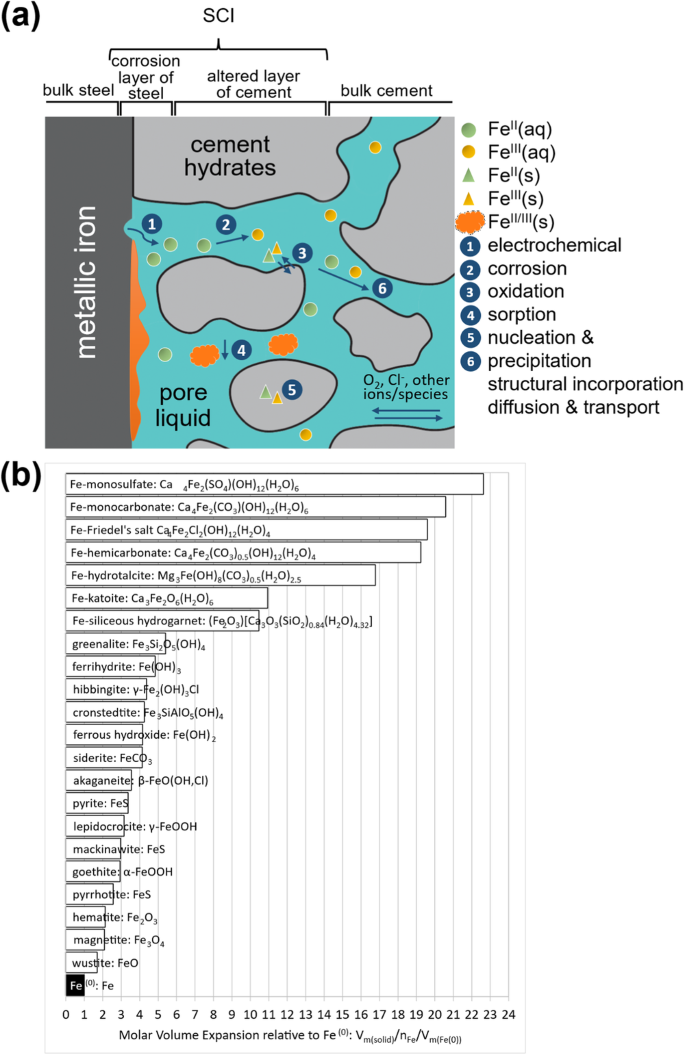

Corrosion of steel reinforcement in concrete poses a significant threat to structural serviceability and load-bearing capacity, in particular in the case where the coverage of the reinforcement by concrete is thin. The corrosion process releases ferrous Fe(II) and ferric Fe(III) species, influencing the formation of corrosion products on the steel surface or the diffusion of iron species into adjacent cementitious material. This interaction leads to changes in hydrates at the iron/steel–concrete interface or its vicinity (Fig. 6a)51. Predictive models, like those developed by Stefanoni et al.52, consider parallel processes such as iron dissolution, diffusion, oxidation, and precipitation of iron-containing minerals, offering insights into steel corrosion in concrete structures and its implications for the long-term safe disposal of radioactive waste in deep geological repositories (DGR)53,54,55.

a Schematic representation of the SCI and the interconnected processes (numbered 1–6) related to corrosion (adapted from ref. 51). b Relative volumes of potential corrosion products and Fe cement hydrates compared to pristine Fe(0), calculated as the molar volume of the secondary iron phase per moles of iron in the solid, relative to the molar volume of Fe(0) (adapted from ref. 17). The solids presented have idealized formulas, and in real cement, they may exhibit different degrees of hydration, affecting the phase volume. Molar volumes obtained from various sources58,59,60,61,62.

Under different physico-chemical conditions (solution properties, moisture availability, temperature, etc.), the nature and content of stable Fe-containing cement phases and corrosion products will vary. Steel corrosion, at the time the passivation effect of the cement material is lost, and the ensuing net volume increase (Fig. 6b) may compromise the integrity at the cement/steel interface, inducing mechanical stress and cracking. The chemical and solid-phase evolution at the steel–concrete interface is contingent upon the stability of formed Fe-containing phases under changing conditions, influencing properties such as Eh, pH, ionic strength, mineralogy, and porosity56.

Conclusions

The extremely long desired service life of cementitious barriers in radioactive waste repositories imposes exceptional demands on long-term material performance, chemical durability, and degradation resistance. Over geological timescales, the intricate geochemical evolution of the cementitious near field, which is predominantly PC-based, is a complex process gaining significant attention. Focus areas include the degradation of cement phases and concrete, alongside interactions with host rocks and other engineered barrier materials.

In general, concrete evolution unfolds across 3-4 stages, influenced by factors such as pore saturation, pore solution exchange rates, aggregate reactivity, and carbonation. During concrete/cement degradation the pH is successively lowered in each stage, which causes ultimately the loss of the favorable alkaline chemical environment for steel passivation and strong radionuclide retention. The interaction between cement and adjacent clay minerals is primarily driven by the concentration gradients in OH−, Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, AlO2−, SiO32−, CO32−, etc., resulting in the long-term formation of secondary minerals, such as C-(A)-S-H, zeolites, and carbonates, as well as in changes in porosity, mechanical and transport properties near the material interface. It is to be noted that in particular in clay host rocks, the high impermeability of the rock and limited availability of water may delay the saturation of a repository for tens to hundreds of thousands of years17. Limited availability of water, also related to consumption of the available cement porewater by chemical reactions, will cause a halt of the degradation reactions until water is again available. This therefore contributes to the service lifetime of the cement-based materials in a clay host rock.

Mechanisms that drive concrete degradation are the internal reactions such as aggregate-cement reactions, the interaction with host rock (and its associated waters) and the contact with other barrier materials including backfill clay or steel. Some of these processes are well investigated, which allows to develop design measures to ensure functionality of the engineered barrier system. One example is the use of inert aggregates, when possible. However, many other aspects require further analysis. Challenges persist; specifically there are uncertainties in long term chemical reactivity of aggregates and the influence of partial water saturation on (bio)chemical and transport processes. The complex nature of these aspects plays a vital role in determining the overall safety of cement-rich deep geological repositories, underscoring the pivotal importance of cement phases in maintaining repository integrity.

Responses