The evolution of lithium-ion battery recycling

Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are being used for a growing range of applications to reduce global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, including electrified mobility and stationary energy storage. Almost 14 million new electric vehicles (EVs) were registered globally in 2023, a 35% increase year-on-year from 2022 (ref. 1). Although China continues to dominate new and total EV registrations, in 2023, new registrations in the United States and Europe increased by 40% and 20%, respectively, relative to 2022 (ref. 1). In North America alone, existing and announced gigafactories should soon be producing more than 1 TWh of battery capacity2. This projected growth in battery production will lead to a future influx of materials into the nascent battery recycling infrastructure.

For approximately another decade, the dominant feedstock for the growing network of battery recyclers will be manufacturing scrap from gigafactories, which typically incur high scrap rates in their first years of production3. Eventually, more complex end-of-life (EOL) batteries will enter the waste stream. EOL batteries pose additional challenges for recycling, owing to their diversity of chemistry and pack design4, as well as the need to safely discharge and dismantle packs, which are getting larger and heavier and becoming more integrated into the EV architecture.

Given the escalating demand for LIBs and the substantial environmental challenges posed by spent LIBs, efficient and sustainable recycling processes are urgently needed. Battery recycling typically starts with a pretreatment step5,6, during which the feed is converted into a black mass, alloy or matte intermediate, followed by metallurgical processing to extract the battery metals and convert them into refined intermediates or precursors. In an ideal circular supply chain, these intermediates or precursors would then be used in the synthesis of new battery active materials7. However, further processing is often needed, leading to concerns over increased operational complexity, secondary pollution and reduced quality of the recovered materials4,7. For example, impurities in the black mass can increase the need for chemicals during purification and extraction, exacerbating environmental impacts and operational complexity4. Additionally, the intermediate materials generated during pretreatment can influence the recovery efficiency and effectiveness of downstream processing and conversion to battery materials5.

The fast evolution of battery designs also poses substantial challenges in disassembly of batteries, affecting the recovery efficiency, product purity, yield rate and cost of pretreatment processes4. Moreover, the pursuit of higher energy densities and longer cycle life has fuelled advances in battery materials and chemistries, which are expected to result in a mismatch between spent battery materials and current market demands4. Thus, battery recycling processes must be able to transform obsolete battery chemistries into materials that satisfy present market preferences.

Advanced methods that enhance efficiency and environmental sustainability are emerging to address drawbacks of current recycling technologies. Direct recycling and upcycling preserve or improve material functionality, whereas deep eutectic solvents (DESs)8 and supercritical CO2 offer alternatives for metal extraction9. Bioleaching uses microbial processes for low-energy metal recovery10, and external-field-assisted methods (for example, ultrasound and microwave fields) improve reaction rates. These approaches collectively expand LIB recycling beyond metals to include additional valuable components, marking a shift toward more comprehensive and sustainable solutions.

In this Review, we describe the evolution of LIB recycling towards more efficient and sustainable processes. We begin by discussing pretreatment processes at the industrial and laboratory scales, and next evaluate established recycling methods, such as pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes, and explore developing techniques, such as direct recycling and upcycling. We also outline possible uses of materials recovered from the cathode, anode and other battery components. We then discuss the interacting economic, environmental and social implications of the different approaches to battery recycling. Finally, we underscore the need for continuous innovation, standardization and collaboration to address challenges in LIB recycling such as impurities from coatings and dopants, and the separation of next-generation lithium-based batteries and materials.

Pretreatment processes

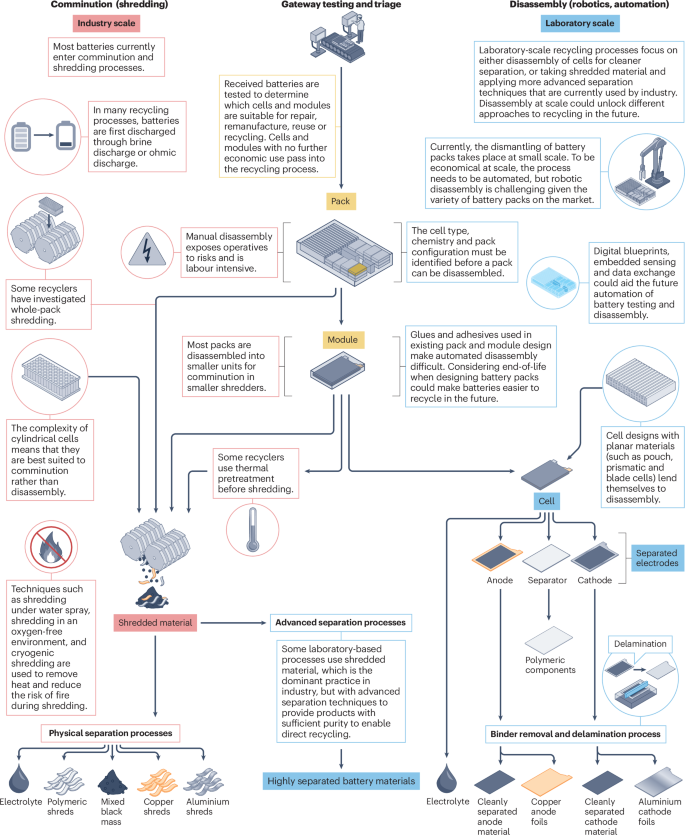

LIB recycling begins with the pretreatment steps that take EOL EV packs from the point of removal to the point at which secondary materials, such as the cathode, anode, current collector, electrolyte and separator, can be refined and fed into subsequent recycling processes (Fig. 1). First, batteries are gateway tested to triage whether they are suitable for repair, remanufacture, reuse or recycling. Gateway testing is a manual process for sorting spent LIBs according to the information from their battery management system and according to different key parameters, such as capacity and impedance, from various measurements, such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy11. Following gateway testing, batteries identified for recycling then undergo pretreatment through one of two processing routes — comminution or disassembly.

Pretreatment approaches vary depending on their development scale. Industry-scale pretreatment processes are based on shredding (left, red), whereas laboratory-scale processes focus on disassembly and the clean separation of materials without mixing (right, blue). Both approaches require disassembling battery packs into modules (centre, yellow).

In the comminution route, used in industrial processes, battery materials are shredded, which results in them being mixed before being separated. Shredding usually happens at the module level; however, some manufacturers have also investigated whole-pack shredding12. Various physical13 techniques are used in industry to sort the resulting shredded material. Magnetic separation can be used to separate magnetic fractions, followed by sieving of the resulting black mass (containing anode and cathode materials, as well as small amounts of other parts) and a range of processes, including flotation, electrostatic separation and air separation, used to sort the size fractions14.

In the disassembly route, spent LIBs are separated manually. Sorting is not needed as the different parts of spent LIBs are not mixed together13. Manual disassembly has the potential to result in a high yield of recovered material (≥80% of the total LIB mass) but is labour intensive and more challenging than shredding to achieve on an industrial scale15. Thus, disassembly is currently conducted only in the laboratory and is restricted to certain cell types, such as planar cells.

In both routes, risk management is important to ensure the safety of those involved16. Steps are therefore taken to help mitigate several risks, including the high voltage in packs, the reactivity of metallic lithium that might be present in packs, and the evolution of hydrogen fluoride (HF) gas from the lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) electrolyte16. In some processes, the cells must first be discharged before shredding or disassembly. Ohmic discharge can be achieved by creating a circuit, which involves making electrical contact with the battery terminals. There is the possibility for concomitant albeit negligible energy recovery; however, this energy can be offset against the plant cooling load17. As this approach requires precise contact to be made with the battery terminals, it is labour intensive, but there is scope for robots to automate this process18. Some laboratory-scale processes for electrode delamination rely on cells being at a known state of charge to reduce risks of overcharging or deep discharging19; such a method would aid this. Alternatively, a less labour-intensive method is to immerse LIBs in brines (aqueous solutions of halide salts), which is simpler and negates the need to accurately connect with the battery. However, this method can lead to corrosion17 owing to the reaction between the salts and battery materials. Conductive powder has also been tested as a method of discharge; this method is simple to effect without the disadvantage of reacting with battery materials, but it may cause thermal runaway17.

To help with discharge safety, cells can be stabilized during shredding through chemical passivation. Thus, comminution is commonly conducted under an inert gas, such as CO2 (ref. 20). When LIB packs are opened under CO2, a passivating layer of lithium carbonate forms on exposed lithium metal. Alternatively, spraying water during shredding leads to hydrolysis of exposed lithium and dissipates heat17,20. Thermal pretreatment is another method commonly used in industry to discharge and disintegrate cells14. Cryogenic pretreatment could be a safe, but potentially energy-intensive, alternative for comminution at low temperatures14.

To increase the recovery of critical materials from EOL batteries, materials need to be separated more cleanly into waste streams, which would simplify the subsequent recycling processes and open the door to direct recycling. In the future, with integrated sensing, it is possible that gateway testing could be eliminated, and the data read directly from the battery. Moreover, future LIB recycling will ideally keep materials in a high-value state for as long as possible21. To this end, more sophisticated methods for separating shredded materials to obtain cleaner materials streams are being investigated at the laboratory scale. If batteries could be disassembled, instead of shredded, there is potential for cleaner mechanical separation to produce material streams that require less post-treatment to separate, resulting in the recovery of materials in a higher-value state15,22. Automation could potentially reduce the cost of this process and enable disassembly at scale, which would be a key enabler of a circular economy. However, robotic disassembly is still in its infancy23,24. Digital blueprints created by embedded sensing and data exchange could aid the future automation of battery testing and disassembly by directly obtaining the status of EOL batteries. Moreover, as shredding usually happens at the module level, the disassembly of battery packs is required prior to shredding to obtain battery modules. However, some elements of battery design frustrate the disassembly of battery packs, particularly the use of adhesives, which limit disassembly options and result in contamination and mixed phases post-shredding25. Although recycling must deal with current LIBs that are in production, there is scope to redesign LIBs for circularity to aid their repair, remanufacture, reuse and recycling26.

Industrial recycling processes

Industrial battery recycling processes are based on pyrometallurgical or hydrometallurgical technologies and use spent LIBs to generate valuable products, such as transition metal salts and transition metal alloys. In this section, we introduce the procedures involved in these two recycling processes and consider their advantages, disadvantages, advances to established methods, and current commercialization.

Pyrometallurgical recycling

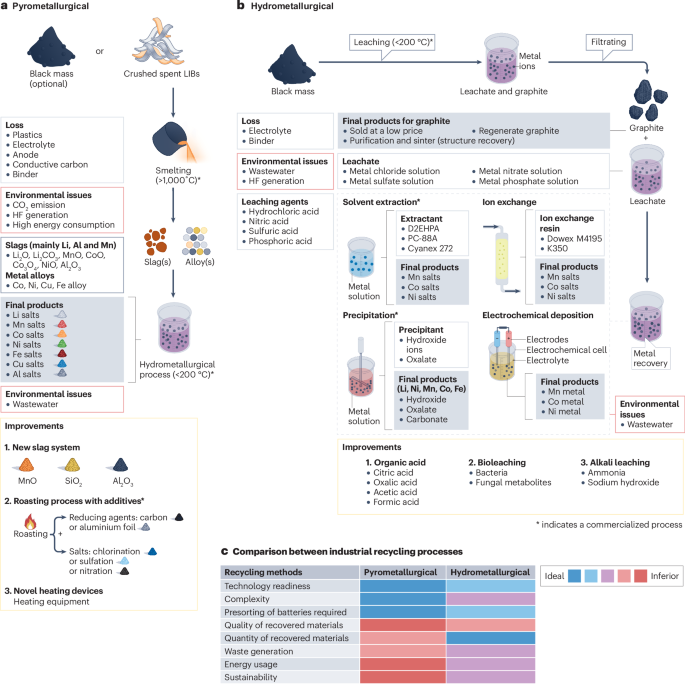

The pyrometallurgical recycling process (Fig. 2a) has relatively simple operating procedures and modest equipment requirements compared with hydrometallurgical recycling and direct recycling processes, making it particularly suitable for implementation on a large industrial scale. Pyrometallurgical recycling also exhibits broad applicability to diverse electrode materials, enabling the recycling of spent LIBs alongside other types of spent batteries, such as nickel–metal hydride batteries27,28.

The industrial recycling of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) is based on pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical methods. a, In pyrometallurgical recycling, whole LIBs or black mass are first smelted to produce metal alloys and slag, which are subsequently refined by hydrometallurgical methods to produce metal salts. The lost materials are the electrolyte, conductive carbon, binder and anode. Environmental issues include CO2 emissions, hydrogen fluoride (HF) generation and high energy consumption. Possible improvements include methods to increase the recovery efficiency and to decrease the cost of the process. b, In the hydrometallurgical recycling process, the metals ions from the cathode materials in the black mass are leached using a strong inorganic acid. The metal ions are subsequently extracted from the leachate to produce metal salts or, in the case of electrochemical deposition, metals. The electrolyte and binder are lost during leaching, whereas the graphite can be recovered. Environmental issues include the generation of wastewater and HF. Possible improvements include methods to optimize the recovery efficiency (alkali leaching) and to limit the issues associated with the use of strong acids (organic acids and bioleaching). c, Comparison of different aspects of the traditional recycling processes. Cyanex 272, bis(2,4,4-trimethylpentyl) phosphinic acid; D2EHPA, di-(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid; PC-88A, (2-ethylhexyl)phosphonic acid mono-2-ethylhexyl ester.

The starting materials for the pyrometallurgical recycling process are either whole LIBs or the black mass obtained from the pretreatment of spent LIBs. The smelting process, conducted at temperatures in excess of 1,000 °C, transforms the spent materials into alloys that contain various metallic elements and generates slags that contain lithium14,29. If starting from spent LIBs, the cases, electrolyte, conductive carbon, binder and anode materials are consumed as fuel in the smelting step. By contrast, if starting from black mass, the cases and current collectors are separated during pretreatment, and only small amounts of copper, iron and aluminium are introduced into the resulting slags and metal alloys. During subsequent hydrometallurgical processing (at temperatures <200 °C), the metal alloys undergo further separation to yield pure metal resources27,30.

Limitations of pyrometallurgical recycling include the reliance on the decomposition of materials and extraction of elements at high smelting temperatures, which is energy intensive and leads to substantial HF and CO2 emissions31,32. Additionally, the hydrometallurgical refining step can be costly and complex and must be considered in comparisons between technologies33. Only high-value metals, such as cobalt and nickel, can be economically recycled using this method; for low-value metals, such as iron in LFP (LiFePO4), pyrometallurgical recycling has little benefit. Lithium recovery is also impractical through most pyrometallurgical processes14,34.

Pyrometallurgical recycling processes have been optimized to mitigate these issues. By introducing graphite and plastic as fuel and reductants, the smelting temperature can be reduced to 500–600 °C (ref. 32). Additionally, innovations related to the slag system have enabled increased recovery of valuable metals. Although the CaO–SiO2–Al2O3 system is commonly used in smelting, it does not allow for the recovery of lithium and manganese14. Consequently, alternative slag systems, such as MnO–SiO2–Al2O3, have been developed that produce lithium-containing manganese-rich slag and a Co–Ni–Cu–Fe alloy35.

To reduce energy consumption, roasting — the recovery of active materials using a reducing agent — can be used to replace smelting and decrease the smelting operating temperature from >1,000 to 500 °C (ref. 14). Strategic additives, such as reducing agents and some salts, can limit energy consumption and increase the extraction rate during roasting. Reducing agents aid the reduction of metal ions in lithiated metal oxide, which is advantageous for subsequent leaching processes as it obviates the need for the reductants typically required in hydrometallurgical processes14,36,37. For example, when iron scrap was introduced as a reducing agent, Fe2+ reduced Ni3+ and Co3+ to Ni2+ and Co2+, respectively, which increased the leaching efficiency of lithium, nickel and cobalt from 81.8%, 50.3% and 43.2% to 94.3%, 88.7% and 96.3%, respectively37. Other examples of reducing agents include carbon32,38, charcoal39, coke40 and aluminium foil41.

Salt-assisted roasting, encompassing chlorination42, sulfation43,44 and nitration45 roasting, has been developed to increase recovery efficiency, decrease acid consumption and minimize toxic gas emissions. Stoichiometric amounts of salts, such as ammonium chloride, can be added to spent LIBs to convert cathode materials into metal salts with different solubilities during roasting42,43,45,46. For example, using sulfuric acid as an additive, lithium is extracted from cathode materials to form Li2SO4, which is then dissolved in water to achieve a lithium leaching efficiency of 99.3%43. Through control of the amount of sulfuric acid, sulfur in the process is in the form of SO42– rather than SOx, which can prevent toxic gas emissions47. In another example, ammonium sulfate is used to covert lithium, nickel, manganese and cobalt into soluble salts with a leaching efficiency of up to 96%48. Similarly, ammonium chloride and nitric acid are used as additives in chlorination and nitration roasting, respectively, achieving leaching efficiencies of up to 99% and 98%42,45. Compared with sulfation roasting (~700 °C)43,44,49, chlorination and nitration roasting are conducted at lower temperatures (~300 °C) as chloride and nitrate are less stable than sulfates and require lower temperatures to react with the metal oxides in battery cathodes42,45.

The design of new heating devices is also a potential method to improve the traditional pyrometallurgical recycling process. For example, the carbothermal shock method has been developed to reduce ternary layered oxide cathodes. This method features a uniform temperature distribution, rapid heating and cooling rates, elevated temperatures, ultrafast reaction times and reduced energy consumption50. After the carbothermal shock process, lithium is selectively leached from lithium oxide using water, achieving a leaching efficiency of more than 90%. Subsequently, nickel, cobalt and manganese are recovered through dilute acid leaching, with efficiencies exceeding 98%50.

These optimization methods are still at the laboratory scale, whereas the industrial pyrometallurgical recycling process (sintering at extremely high temperatures) has been commercialized to obtain metal, metal alloys and metal salts (through further hydro-based refining)51.

Hydrometallurgical recycling

Hydrometallurgical recycling processes extract high-value metals from spent battery materials through chemical reactions with reductants and leaching agents, during the leaching step, within a reactor at temperatures (usually <200 °C) lower than those used in pyrometallurgical recycling33,52. Following pretreatment to obtain black mass, hydrometallurgical recycling typically entails two main steps: leaching and separation (Fig. 2b).

During leaching, valuable metal ions are extracted from the cathode materials in the black mass into a solution using a leaching agent, which is typically a strong inorganic acid, such as hydrochloric, sulfuric, nitric or phosphoric acid53,54,55,56,57,58,59. These strong acids are favoured for their high leaching efficiency even at low concentrations53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60. For example, more than 93% of lithium, nickel and cobalt can be extracted from spent cathode materials using 1 mol l–1 sulfuric acid at 90 °C (ref. 60). Valuable metal ions in the leachate can then be separated by different methods, including solvent extraction61,62,63,64,65, chemical precipitation66,67,68, ion exchange69 and electrochemical deposition70,71,72. The graphite (anode material) in the black mass remains solid and can be sold directly or recovered after purification and sintering, whereas the electrolyte and binder materials are lost in the leaching step.

In solvent extraction, metal ions are extracted based on their different solubilities in a tailored organic solvent compared with an aqueous solution. D2EHPA (di-(2-ethylhexyl) phosphoric acid), PC-88A ((2-ethylhexyl)phosphonic acid mono-2-ethylhexyl ester) and Cyanex 272 (bis(2,4,4-trimethylpentyl) phosphinic acid) are common extractants61,62,63,64,65. By contrast, in chemical precipitation, various metals are precipitated by adjusting the pH of the leachate66,67,68. Using electrochemical deposition, metal ions are selectively separated from the leachate based on differences in their electrochemical potential70,71,72. Metal ions can also be recovered from the leachate through an ion exchange method, based on different properties, such as ion sizes, charges and concentration69.

Compared with pyrometallurgical recycling, the hydrometallurgical approach requires less energy, owing to the lower operating temperatures and shorter reaction times (usually under 3 h)53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60 (Fig. 2c), but requires extra pretreatment steps to obtain black mass as well as more complex equipment. However, as hydrometallurgical processing uses black mass rather than whole batteries, some components of spent LIBs, such as plastics and current collector, can be separated and recovered post-shredding73. Moreover, in the hydrometallurgical approach, some chemicals can be reused, and the process can be optimized to synthesize cathode materials for next-generation batteries. Extra acid can be reused, whereas in the pyrometallurgical process additives cannot be reused11. Moreover, after removing impurities, the leachate can be directly used to synthesize precursors for new batteries, whereas the products of pyrometallurgy cannot be directly used to synthesize cathode materials7.

Nonetheless, hydrometallurgical recycling has several disadvantages. As the recovery process is complex, graphite is normally sold at a low price, and it is not clear whether recovered graphite can find a useful application that delivers an economic or sustainability advantage46,74. The use of inorganic acids raises concerns about operational safety, secondary pollution and potential equipment corrosion during the leaching process75,76. The generation of secondary pollutants, such as wastewater and gases, when the electrolyte is dissolved in the acids, creates a need for additional and costly treatment processes77,78. Moreover, the separation of some elements, such as aluminium, copper, nickel, manganese and cobalt, in solution is a challenge owing to their similar properties79. Organic acids can be used to replace inorganic acids during leaching. As organic acids can be easily degraded and recycled80, less secondary pollution will be generated. However, organic acids are expensive.

Alternatively, bioleaching exploits the metabolic processes of microorganisms10 to generate acid for the leaching step. To make the separation step easier and to reduce the need for expensive purification steps, alkali leaching has gained interest for its ability to selectively leach aluminium, which is an amphoteric metal and dissolves in both acidic and alkaline solutions81,82. In alkali leaching, the alkali solution NH3–(NH4)2CO3–Na2SO3 and sodium hydroxide can be used as a leaching agent to selectively leach aluminium ions, as metal aluminium can be dissolved in both acidic and alkaline solutions81,82. Sodium hydroxide can also be used during alkali leaching because it can selectively remove aluminium, while cobalt, nickel and manganese remain insoluble in the alkaline solution83,84,85.

Hydrometallurgical recycling processes have been commercialized by multiple companies. Reported processes include hydrometallurgical recycling to recover metal sulfates and lithium phosphate from spent LIBs86,87. Also reported are hydrometallurgical processes for hydro-to-cathode direct precursor synthesis, directly using the leachate after removing impurities to synthesize precursors by co-precipitation reaction88,89,90. Finally, a combination of hydrometallurgical and pyrometallurgical methods has been reported in which spent LIBs are first smelted to produce a Co–Ni–Cu–Fe alloy, and then the alloy is leached and metal ions from the alloy are separated by hydrometallurgical methods91.

Developing recycling processes

Various advanced recycling techniques are emerging to achieve greater recovery efficiency and to minimize waste, optimize resource recovery and lessen the environmental impact of the recycling process. In this section, we outline the latest advancements in recycling technologies, examining how they operate and their potential for commercialization.

Direct recycling

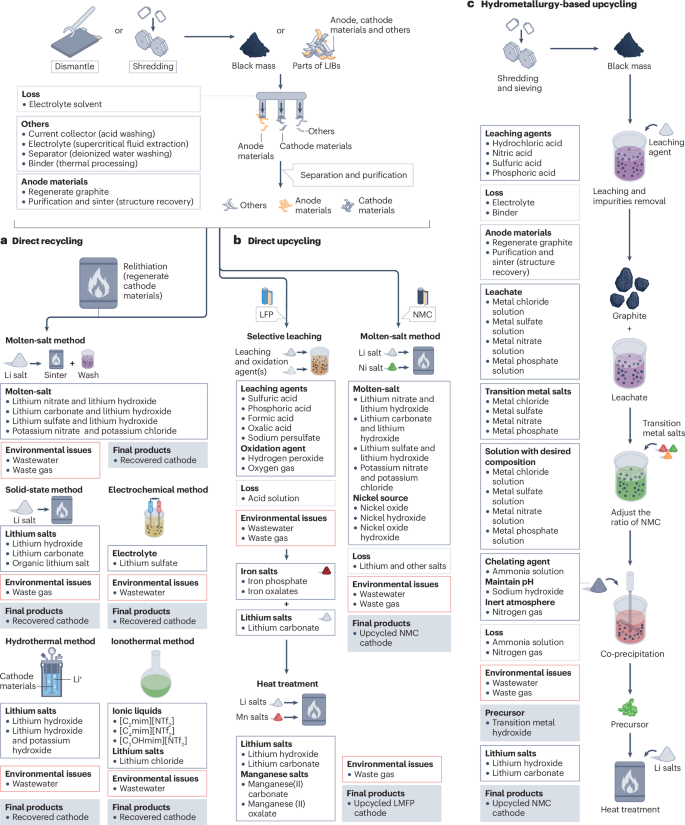

In direct recycling, the cathode materials are processed without breaking down their crystal structure. Spent batteries are first manually disassembled and separated into different parts (Fig. 3a), and the cathode materials are subsequently recovered through a relithiation process92. As the battery materials are separated during disassembly, and all materials, especially cathode materials, are not broken down in subsequent steps, direct recycling should recover almost all materials from spent LIBs, including the cathode93,94,95, anode96,97, separator98, current collectors99, binders100 and others101. Direct recycling involves unit operations that repair the structure and composition of degraded battery materials. For example, lithium is consumed in side reactions during cycling102. Relithiation replaces the lost lithium in the cathode and can be realized through solid-state94,103, molten-salt104,105, electrochemical106, hydrothermal95,107 and ionothermal108 relithiation reactions. Each of these methods offers distinct advantages and faces unique challenges regarding feasibility and commercialization potential.

Advanced lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling processes include direct recycling, direct upcycling and hydrometallurgy-based upcycling. a, Starting from black mass or separated materials obtained from disassembling the battery packs, direct recycling can recover all battery materials. The current collectors, electrolyte and separator can be directly reused after purification, whereas anode materials can be reused after purification and sintering to recover the structure. Cathode materials are purified and relithiated to replace the lithium lost during cycling. The relithiation methods generate wastewater and/or waste gas (usually CO2). The molten-salt reaction generates waste gas in the sintering step, and wastewater in the washing step. The solid-state reaction only generates waste gas, and the electrochemical, hydrothermal and ionothermal methods only generate wastewater. b, Direct upcycling is similar to direct recycling, except for the relithiation step, in which additional salts are introduced to tune the cathode composition. There are two main cathode materials for upcycling: lithium iron phosphate (LFP) and nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC). LFP can be upcycled to lithium manganese iron phosphate (LMFP), whereas NMC materials can be upcycled to nickel-rich cathode materials. Both upcycling processes generate waste gas and wastewater. For LFP, waste gas and wastewater are generated in the leaching step, and only waste gas is generated during the heat treatment. For NMC, a washing step is required during the heat treatment, and both waste gas and wastewater are generated. c, Hydrometallurgy-based upcycling is similar to hydrometallurgical recycling but requires one more step after the leaching and purification steps, which is to adjust the ratio of metal ions in solution by introducing extra nickel, manganese and cobalt salts to achieve the desired composition of the upcycled NMC cathode materials. A precursor is then synthesized by co-precipitation and mixed with lithium salts to produce upcycled NMC cathode materials by heat treatment. The process generates wastewater and waste gas during the co-precipitation reaction, and waste gas during the heat treatment.

In the solid-state reaction method, spent cathode materials are heated with a lithium salt. During the reaction, the degraded structures and lithium loss are repaired. Although simple, this method requires high temperatures (above 600 °C) and prolonged processing times (over 5 h), making it energy intensive and raising concerns about the formation of impurity phases109. The high temperature and extended treatment can cause the formation of rock-salt phases on the surface of the cathode, resulting in poor performance109. The layered structure of spent NMC532 (LiNi0.5Mn0.3Co0.2O2) was repaired and lost lithium was replaced through a two-step sintering process at 500 °C, for 5 h, and 900 °C, for 12 h. Compared with commercial NMC532, the rate performance of the recycled NMC532 was 3% inferior and the cycle performance was similar110. Spent LFP has been recovered using an organic lithium salt under a reducing atmosphere at 800 °C for 6 h (ref. 111).

The molten-salts method uses a lithium-containing molten salt — a eutectic mixture of salts that forms a homogeneous liquid at elevated temperatures — as reactants or melts, such as Li2CO3–LiOH (ref. 112), Li2SO4–LiOH (ref. 113) or LiNO3–KNO3–KCl (ref. 114), to increase the diffusion of lithium and enable the reaction in solid and liquid states115, and thus aid the relithiation of spent cathode materials. This method operates at lower temperatures than the solid-state reaction method, enabling relithiation in a molten-salt system at 300 °C or 500 °C (refs. 116,117,118). However, some relithiation processes require lithium salts to decompose at temperatures exceeding 800 °C with shorter annealing times104,116. Additionally, the use of extra salts introduces challenges, such as the need for specialized equipment and additional steps for salt removal. The need for extra chemicals and washing steps, which can also lead to lithium loss and cation mixing, increases the cost of the process and moderates its commercialization potential. Using this approach, spent LCO (LiCoO2) was relithiated by heating with a mixture of Li2CO3, KOH and LiOH (with a molar ratio of 0.5:7:3) at 500 °C for 8 h (refs. 117,118). The extra lithium salts were washed out, and relithiated LCO was then obtained with a fixed layer structure and original rate and cycle performance. However, spent NMC532 was relithiated by using eutectic molten salts LiOH and Li2CO3 at 440 °C for 5 h, and then the layered structured was repaired at 850 °C for 12 h. The different conditions are determined by different feedstocks and different molten-salt systems116.

Electrochemical relithiation can directly recover cathode materials through an electrochemical process by controlling the intensity of voltage, current, pH and electrolyte composition. Compared with other relithiation methods, electrochemical relithiation produces less wastewater, reduces the usage of reagents and avoids needing to peel cathode materials from current collectors. However, the complexity of the electrochemical cell set-up and the inability to fix cathode cracks limit its commercialization potential. Electrochemical relithiation has been used to repair LCO119 and LFP120. LCO was repaired in an aqueous electrolyte followed by a heat treatment, whereas LFP was recovered in an electrolyser with a zinc plate anode and a Li2SO4 electrolyte by a discharge process.

In the hydrothermal method, lithium salts are dissolved in an aqueous solution and after the spent cathode materials are added, high pressure and moderate temperature (25 bar at 220 °C)121 are applied for relithiation, followed by a short (less than 10 h)121 annealing treatment to recover the degraded structure. This approach uses water as a low-cost reaction medium and reduces energy consumption by eliminating the need for dehydration, accelerates reaction rates by acting as a medium, reactant and catalyst, and prevents secondary pollution through a sealed environment122. Nevertheless, the need for high pressures might limit its widespread adoption. Spent LiNi0.15Mn0.15Co0.70O2 was relithiated through a hydrothermal method at 220 °C, for 2 h, and then sintered at 850 °C, for 4 h, in air123. The recycled cathode materials achieved a discharge capacity of 150.7 mAh g–1 at 0.33 C in the first cycle, with a capacity retention of 91.2% after 50 cycles. LFP was also recovered through a hydrothermal method and showed better rate performance, and comparable cycle performance under 0.5 C after 100 cycles95, compared with commercial LFP.

The ionothermal relithiation method leverages negligible vapour pressures, nonflammability, wide liquidus ranges, good thermal stability and synthesis flexibility of ionic liquids, but requires high-cost solvents, thus lowering its commercialization potential124. Reusable ionic liquids and LiCl were used to relithiate NMC111 (LiNi0.33Mn0.33Co0.33O2) cathode materials, at 150–250 °C. After separation from the ionic liquids, the recovered NMC111 was obtained with a 98.9% yield, slightly lower than other direct recycling processes, and demonstrated an electrochemical performance comparable to commercial NMC111 (ref. 108). The yield could be further increased during scale-up, as the loss primarily occurred in the separation step108.

Although all these methods show promise in regenerating cathode materials with comparable or superior electrochemical performances to those of commercial cathode materials, direct comparisons remain difficult owing to variations in feedstocks (many studies use commercial materials or delithiated materials to simulate the real degraded materials), test procedures and evaluation metrics. Standardized feedstocks and testing protocols, and further research, are necessary to fully assess the feasibility and commercialization potential of these relithiation techniques.

Moreover, the relithiation process is challenged by coatings or dopants on cathode materials, such as carbon on LFP to increase the conductivity and metal or non-metal element coatings or dopants on nickel-rich cathodes for enhanced stability. The presence of coatings and dopants might require repairing damaged coating layers or could hinder lithium diffusion during the relithiation process. Over long cycles, these coatings can degrade111 or react with electrolytes, forming new compounds125,126 that affect their protective properties. Despite the importance of the topic, studies on recovering coatings and dopants during direct recycling are limited. Whereas carbon coatings on LFP can be relatively easily restored by adding more carbon95,111, recovering metal or non-metal-based coatings and dopants on NMC (LiNi1–x–yMnxCoyO2) cathodes is more complex owing to chemical changes during cycling95,111,127.

Cracks, caused by mechanical stresses128 during cycling, are another typical challenge in direct recycling. These cracks can be repaired through a calcination step110, during which high temperatures (over 900 °C) help to heal small cracks by promoting the growth of primary particles. However, this process can also result in a more porous structure110 or cause further cracking, leading to irregularly shaped recovered cathode materials129,130.

A key challenge for direct recycling is that it requires exceptionally effective material separation and purification. Black mass contamination by other parts of spent LIBs is more problematic in a direct recycling process than in a conventional hydrometallurgical one, because the methods available to remove impurities are constrained by the need to preserve the original cathode molecular structure131. Although methods based on flotation or use of a heavy liquid, for example, have been developed for the separation of black mass132,133 or different types of cathode materials133,134, with a purity of more than 95%, the type of impurity is not always reported, despite this affecting the quality of recycled cathode or anode materials.

By eliminating many of the steps usually needed in the complex series of material transformations of other recycling processes, direct recycling avoids some of the costs and environmental burdens. For example, a direct recycling process involving shredding, rather than dismantling, has an estimated potential saving of up to 50% of the cathode manufacturing cost135,136 for NMC chemistries and around 70% for LFP95 compared with the manufacturing cost of virgin cathodes. EverBatt, Argonne National Laboratory’s battery recycling process and supply chain model, estimates that commercialization of direct cathode recycling could decrease recycling costs by 40%136. However, direct cycling also faces practical challenges as the recycled cathodes retain their original compositions and structures. Vehicle batteries can last 15 years or more4,137, but battery cathode chemistries are constantly evolving and improving. The performance of a 15-year-old chemistry will be inferior to that of more recent chemistries and will no longer be demanded by the market. Thus, direct recycling will probably find its first commercial use in the processing of manufacturing scraps, as the material chemical composition will be current. As the product is a cathode material, locating a recycling plant at the cell manufacturing site would enable the recycled material to be introduced back into the cell production line.

Although there was limited research on direct recycling until about the early 2010s, there are now potential solutions to some of the challenges. Several start-up companies are reportedly demonstrating success at the pilot stage, with a small number of commercial demonstrations expected over the next few years.

Direct upcycling

Upcycling entails upgrading the composition of recovered materials during the recycling process136. Developed from direct recycling, direct upcycling also targets the recovery of intact cathode materials but strives to modify the original compound such that the recovered cathode materials have a more advanced composition than the spent cathodes. With this approach, the chemistry of the recovered cathodes can be tailored to match market preferences and to enhance the competitiveness of the recycled material136. Compared with direct recycling, the relithiation process is optimized in direct upcycling through the introduction of additional metal salts to tune the composition of the recovered materials138 (Fig. 3b). Thus, direct upcycling shares the advantages of direct recycling but also offers more flexibility in the chemical composition of recovered products113. However, this strategy is still at the laboratory scale and thus requires further development and scaling before it can be applied in industrial settings139.

Direct upcycling requires uniform elemental diffusion in the solid phase during relithiation to obtain advanced cathode materials. The molten-salt method is preferred because the molten salt acts as the solvent and enhances the reaction and diffusion of lithium and transition metals. The high temperature (>850 °C)139 and molten salts create a liquid environment that enhances transfer rates and accelerates the diffusion of elements, such as lithium and nickel140. Using this approach, NMC-based cathode materials have been upcycled to single-crystal nickel-rich cathodes by adding nickel salts and lithium salts during heating treatment113,138; the added nickel content increases the discharge capacity and energy density of the cathode, and the single-crystal morphology enhances its stability. Using an alternative selective-leaching approach, spent LFP cathode can be upcycled to LMFP (LiMnxFe1–xPO4). In this approach, FePO4 was leached from spent LFP and then mixed with manganese salts and additional lithium salts to form LMFP following heat treatment. An oxidation agent was used to enhance lithium extraction. The LMFP obtained achieved a discharge capacity of 161.3 mAh g–1 under 0.1 C and 95.6% capacity retention at 1 C after 8,000 cycles141. Unlike the upcycling of NMC cathodes, upcycling of LFP requires the leaching of lithium first, which adds complexity to the process. However, there are opportunities to explore whether spent LFP can be upcycled in one step, similar to the upcycling process for NMC cathodes.

Direct upcycling tackles the challenge of past-generation recovered materials in direct recycling, but challenges remain. When the feedstock is a mixture of spent cathode materials, including LFP, NMC, LMO (LiMnO2) and/or LCO, LFP must be sorted out because its olivine structure cannot be converted into a layered structure, owing to the presence of polyanions. However, materials with a spinal structure, such as LMO, do not require separation from the feedstock, as they can be transformed into a layered structure under specific conditions113. Moreover, the overall percentage of recycled materials in direct upcycling might be low. For example, if upcycling NMC111 to NMC622 (LiNi0.6Mn0.2Co0.2O2) or NMC811 (LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2), only ~60 wt% or 30 wt% of spent materials can be used, respectively, with virgin material needed to adjust to the composition. Also, the nickel sources used in direct upcycling processes, such as nickel(II) oxide and nickel(II) hydroxide, are more expensive than nickel(II) sulfate used in the precursor regeneration stage of hydrometallurgy-based recycling processes, and the extra cost of molten salts further erodes the economic benefit of direct upcycling142.

Compared with direct recycling, direct upcycling is more suitable for recycling outdated cathode materials. However, like direct recycling, the method is limited by the need for strict separation steps. Although it has been demonstrated that mixed feedstock of commercial NMC111 and LMO113, as well as mixed spent NMC532 and conductive carbon138, can be upcycled to NMC622, it remains uncertain whether direct upcycling is feasible for black mass, owing to its complex and variable compositions. Nonetheless, the direct upcycling approach overcomes some of the practical limitations of direct recycling, showing greater potential for commercialization and potentially enabling high recovery efficiency and sustainable recycling technologies.

Hydrometallurgy-based upcycling

The hydrometallurgy-based upcycling process is an optimized version of hydrometallurgical recycling, in which metal salts extracted during hydrometallurgical recycling processes are directly reused in the manufacture of cathode materials. The recycled cathode materials can perform as well as high-quality virgin counterparts143, paving the way to reintroducing recycled materials into new battery manufacturing. Notably, 1 Ah cells with recycled NMC111 achieved 4,200 cycles at 80% capacity retention and 11,600 cycles at 70%, which is 33% and 53% better, respectively, than commercial counterparts143. However, hydrometallurgical recycling processes and cathode production are typically conducted separately. The hydrometallurgy-based upcycling strategy was developed to integrate these recycling and production processes144 (Fig. 3c). Similar to the conventional hydrometallurgical recycling process, spent batteries are first disassembled or shredded and then leached with strong acid. Next, impurities, such as copper, iron and aluminium, are removed from the leachate by a simple two-step pH adjustment. Iron is first removed at a pH of 2.815–5.156 (ref. 144), followed by copper and aluminium impurities by increasing the pH to 6.47 (ref. 145).

Unlike the conventional hydrometallurgical recycling process, the hydrometallurgy-based upcycling process avoids complex and costly extraction steps. The ratio of metal ions in the leachate is adjusted by adding virgin metal salts to attain target metal ratios. A subsequent co-precipitation reaction with a chelating agent, followed by heat treatment, generates the desired cathode material to meet market demands146. The co-precipitation reaction occurs under an adjusted pH to control the morphology and an inert atmosphere to prevent the oxidation of transition metals. With this method, the overall recycling rate of valuable transition metals is more than 90%147, and 80% of lithium can be recycled as Li2CO3 after a co-precipitation reaction by controlling the solubility of Li2CO3 in water, which is comparable to the lithium extraction rates of hydrometallurgical recycling processes51. A mixture of spent cathode materials including LCO, LMO, LFP and NMC111 can be recycled to produce new NMC111 cathode powder146,148 at a third of the cost of using virgin materials144. The spent graphite can also be recycled with appropriate post-processing137. In addition, the hydrometallurgy-based upcycling process can be used to produce customized cathode materials, such as nickel-rich cathodes, by adjusting the ratio of metal ions in the leachate149,150. However, owing to the different synthesis methods, such as solid-state and spray dry methods, and low added value of recycled LFP cathodes, owing to the cost of chemicals consumption95, they are typically not suitable for hydrometallurgy-based upcycling processes. An economical strategy based on DESs has been used to upcycle mixed LFP and LMO cathodes into LMFP cathodes151.

The hydrometallurgy-based upcycling process combines the benefits of hydrometallurgical and direct recycling technologies, increasing the recovery efficiency, eliminating steps, reducing overall chemical utilization and enabling the facile separation of graphite from the transition metals present in the black mass, as well as offering the added flexibility to accommodate input streams of varying content146. The superior quality control and the highly engineered materials achieved by the hydrometallurgy-based upcycling process offer tangible benefits (economic and technical) relative to direct upcycling. The removal of impurities, which remains a key challenge in battery recycling, is more easily accomplished from solution and thus offers another advantage for the hydrometallurgy-based upcycling strategy152. Conversely, direct upcycling largely relies on physical methods for purification, which necessitates strict and costly pretreatment113. Hydrometallurgy-based upcycling technology that generates nickel-rich cathode precursors from black mass has now reached a technology readiness level (TRL) of 8–9, indicating a higher maturity than direct upcycling153. However, optimization is required to maximize recycled materials content in upcycling strategies and reduce the effects of secondary pollution caused by use of chemicals.

Other developing recycling processes

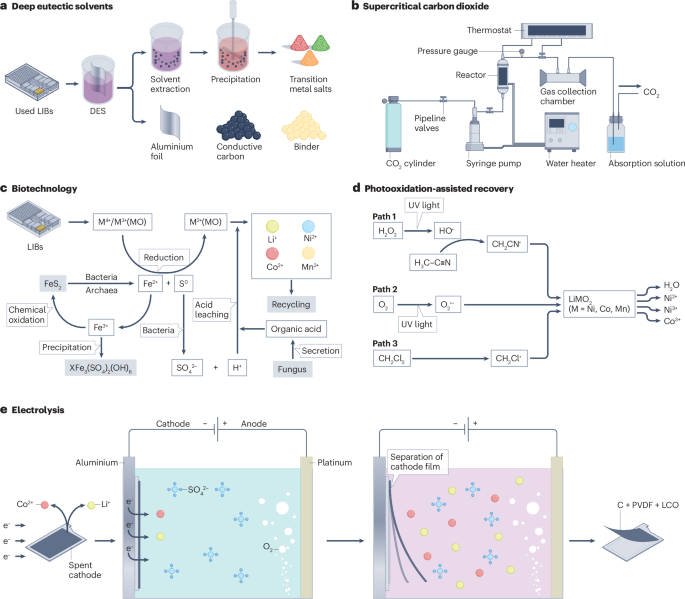

Advanced recycling technologies are being developed to reduce secondary pollution and the cost of the recycling process, including processes based on the use of DESs, supercritical CO2, biotechnology and electrochemical methods.

DESs are a class of solvents that offer properties such as biodegradability, ease of synthesis, low volatility and high safety in terms of toxicity and corrosion154,155. In a variation of hydrometallurgical recycling, DESs are used as the leaching agent (Fig. 4a). The main step of the process is the optimization of the leaching conditions, primarily by adjusting the molar ratio of the composition of the DES, water content, leaching temperature and duration, and the solid-to-liquid ratio156. A DES comprising choline chloride and ethylene glycol has achieved a leaching efficiency of more than 90% for lithium and cobalt from LCO8. Moreover, a DES comprising p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate and choline chloride leaches up to 94% of the cobalt from spent LCO. Additionally, using this method, the mixture of spent LFP and LMO could be upcycled to LMFP, achieving a discharge capacity of 152 mAh g–1 with an initial coulombic efficiency of 94% and a capacity retention of more than 99.5% at 1 C after 200 cycles. However, these processes were developed at the laboratory scale, and the recovery rate and leaching efficiency with DESs are lower than those of conventional hydrometallurgical recycling processes8. Thus, larger-scale experiments are needed to assess the commercialization potential.

a, Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) dissolve transition metal oxides in spent lithium-ion batteries (LIBs). The leachate is then filtered to extract the aluminium foil, binder and conductive carbon components before recovering the transition metal salts through precipitation. b, Supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2 above its critical temperature and pressure) can be used as a solvent to extract valuable elements in spent cathode materials. Carbon dioxide (pressurized using a syringe pump) is combined with spent LIBs and cosolvents such as water, methanol, ethene and acetone, in a reactor, which is maintained at the desired temperature by a thermostat water bath. The gas products of the reaction are then collected and cooled to room temperature, producing a liquid containing lithium and transition metal salts. c, Examples of biotechnological approaches to extract transition metals from spent LIBs. The metabolic activity of bacteria leads to the production of Fe2+ and H+, which initiate the reduction and acidic dissolution, respectively, of transition metals such as Li, Ni, Co and Mn. Additionally, organic acid produced by fungi can accelerate the dissolution of metals. d, An example of photooxidation-assisted recovery in which an external ultraviolet (UV) field is used to generate free radicals such as HO· (path 1), O2· (path 2) and CH2Cl· (path 3) to extract Co and Ni from cathodic material such as LiMO2 (M = Ni, Co, Mn). e, An example of the use of electrolysis to recycle a spent LiCoO2 cathode. Electrons from H2SO4 are directed to the cathode where they act as a reducing agent, separating the cathode film from the aluminium foil and extracting lithium and cobalt into the solution. LCO, LiCoO2. Panel b adapted from ref. 100, CC BY 4.0. Panel c adapted with permission from ref. 225, Elsevier. Panel d adapted with permission from ref. 174, American Chemical Society. Panel e adapted with permission from ref. 226, Royal Society of Chemistry.

Supercritical CO2 refers to CO2 that is in a state above its critical temperature and pressure, at which it displays properties between those of a gas and liquid (Fig. 4b). These properties enable supercritical CO2 to penetrate materials like a gas while dissolving substances like a liquid. Using supercritical CO2 as a solvent together with a tributyl phosphate–nitric acid adduct and hydrogen peroxide, more than 90% of lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese were recovered from NMC111 and NMC622 (ref. 9). Supercritical CO2 can also be used in processes to recycle the electrolytes and polyvinylidene fluoride binder157. However, owing to the requirements for high pressure (100–1,000 bar) and high temperature (20–200 °C), the supercritical CO2 recycling process is limited by high equipment costs and scale-up issues158.

Bioleaching is an alternative to conventional pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes as it operates under ambient conditions and has lower energy requirements, greenhouse gas emissions and operational costs, as well as fewer contamination and processing hazards159. Biotechnological approaches leverage biological processes, specifically the metabolic actions of bacteria and other microorganisms, to break down minerals and extract valuable metals from spent LIBs (Fig. 4c). Leaching efficiencies of 10–100% of lithium and transition metals have been achieved using different microorganisms10,160,161,162,163. However, bioleaching generally takes longer (~7 days) than chemical processes, which is a drawback for industrial-scale operations requiring quick turnaround times10. Furthermore, the reaction conditions must be carefully controlled to maintain microbial activity, which limits the scaling from laboratory settings to industrial operations.

Other variants of the hydrometallurgical recycling process use an external field to assist metal recovery, with the aim of decreasing chemical consumption and increasing the recovery efficiency (Fig. 4d,e). For example, electrochemical methods have been developed in which the applied current replaces the reducing agents to increase the recovery efficiency and decrease environmental pollution164,165. Other external fields, such as ultraviolet light, ultrasonic waves166,167,168,169, microwaves170,171,172 and photooxidation173,174, can be used to accelerate the leaching process, increase leaching efficiency and reduce the usage of leaching agents175. An approach that uses ultrasonic fields to increase the surface area and microwave fields to decrease the activation energy for the reaction, can achieve recovery rates of more than 95%175. However, these technologies are challenged by limited processing capacity, uneven distribution of external fields and high costs176.

In summary, several advanced recycling technologies have been developed to minimize secondary pollution, reduce costs and enhance efficiency in the recycling process. Despite their potential, these innovative methods encounter considerable challenges, particularly in terms of scalability, which remains a critical hurdle to their commercialization.

The use of recovered materials

Recycled materials have traditionally been considered inferior to virgin materials and only applied to low-value applications. If true, this would make them unsuitable for new battery production. In this section, we discuss how recycled materials can be reintroduced into new batteries. Spent cathode and anode materials, as well as other materials such as the current collector, electrolyte, binder and separator, are among the potential recycled materials.

Materials from the cathode

Recycling critical materials from spent LIB cathode materials can improve resource efficiency and sustainability of the battery supply chain. In this section, we discuss recycling strategies focused on the recovery of lithium and transition metals.

Lithium from spent cathode materials

Lithium is extracted from spent LIBs by hydrometallurgical recycling through either an up-front hydrometallurgical recycling process of the cathode materials and the selective recovery of lithium, or a post-hydrometallurgical recycling process of the cathode materials after the transition metals have been removed. One method of hydrometallurgical recycling process for lithium recovery, at the laboratory scale, is heat treatment of the black mass followed by selective leaching of the lithium. When this process is conducted under an inert or reducing atmosphere, the lithium from the cathode materials is converted into lithium carbonate177 The lithium carbonate can then be dissolved in water and precipitated. The main disadvantage of this process is that the recovery rate is typically below 90%178,179,180,181. If hydrogen gas is instead used during the heat treatment, lithium is converted into lithium hydroxide182. Recovery of battery-grade lithium hydroxide has been demonstrated with a 94% recovery rate183. Another approach is to use organic or weak acids to directly recover lithium. For example, using formic acid, at the laboratory scale, lithium was extracted with a recovery efficiency of up to 98%80. When lithium is instead recovered from cathode materials after nickel, manganese and cobalt have been removed, the resulting leachate is normally pH neutral or basic. A carbonate source is then commonly added to precipitate lithium carbonate180. In all cases, battery-grade lithium carbonate product can be produced (Fig. 5a). Recyclers have the option of producing lithium carbonate or hydroxide for reuse in new batteries; the choice will depend on the capital expenditure and market considerations.

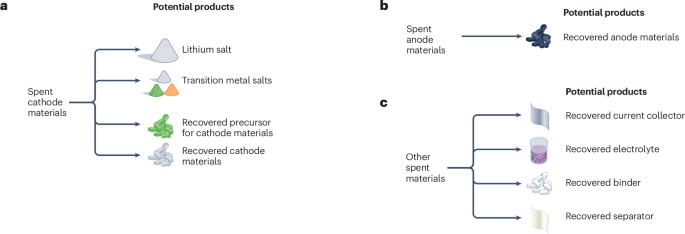

Potential products that can be recovered from spent cathode materials (panel a), spent anode materials (panel b) and other spent battery materials (panel c).

Another emerging consideration relates to fluorine management. Depending on the process design, fluorine might be present in the lithium stream or be passed into the transition metal stream for further refining184,185. Wherever it ends up, it must be handled appropriately as it can form lithium fluoride, which is an impurity in battery-grade lithium salts. Thus, several methods to remove fluorine from lithium solutions, such as recrystallization and selective membranes, have been developed184,185.

Transition metals from spent cathode materials

Transition metals have always been the main focus of LIB recycling, although the primary value driver has shifted from cobalt to nickel. The purity of the product determines the final value186. Whether the LIBs are processed by shredding or pyrometallurgy, the only commercially viable method to produce battery-grade nickel sulfate and cobalt sulfate is solvent extraction187,188 (Fig. 5a). When using pyrometallurgy, a nickel–cobalt alloy or matte is obtained, dissolved and separated through solvent extraction14. With shredding, the resulting black mass is leached and dissolved before purification and separation189.

To be reintroduced into new batteries, recovered transition metals are used to synthesize battery-grade cathode materials and their precursors. The resulting cathode materials can exceed the performance of the virgin materials143. The main challenge with using transition metals in cathode synthesis is the ever-changing market and demands of the battery producers. As the nickel concentration in the cathode chemistry increases, the need for material purity also increases190. Whether this trend is due to the market pushing for an advantage over the competition or higher purity requirements for the most energy dense materials, recyclers must match the specifications required of virgin materials.

Materials from the anode

Graphite has been the traditional anode of choice, although there are numerous emerging alternatives. Graphite anodes have traditionally been downcycled: either burned for their caloric value in pyrometallurgical (and some hydrometallurgical processes) or used in lower-value applications46. Recycling anode materials back into the supply chain is a relatively new concept and is still in the research and development phase191.

Spent graphite recycled through direct recycling and hydrometallurgical processes with purification can be recovered and then reused in battery manufacturing (Fig. 5b). However, recovered graphite obtained from direct recycling faces some challenges such as solid electrolyte interface formation, disordered structure and the formation of lithium dendrites192. Graphite recovered through hydrometallurgical processes faces the same problems, and might also have impurities, such as aluminium, from other parts of LIBs137. To recover graphite anodes, several methods have been developed. Using a chemical purification approach137, approximately 60 wt% of graphite was recovered, and the recovered graphite (96% purity, after sintering) delivered comparable electrochemical performance to commercial graphite137. Through microwave treatment, graphite with 99.43% purity has been obtained193. Graphite can also be recovered by flash recycling, whereby the material is infrared heated to a temperature high enough to melt all residual impurities but not destroy the graphite structure194. To make regeneration easier, graphite can be separated from the anode current collector and directly recovered after purification195.

Materials from other components

The current collectors (both aluminium and copper), electrolyte, binder and separator can also be recycled and reused in LIBs (Fig. 5c). Similar to the recycling of anode materials, recovering these components is a relatively new concept and is still in the research and development phase.

Current collectors can be recovered by direct recycling through washing with HCl or HNO3, whereas aluminium current collectors can be directly recovered through washing with N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone or etching with oxalic acid99. When current collectors are recovered through direct recycling processes, they can be directly used in new batteries after washing98. However, when using industrial recycling processes such as pyrometallurgy, the used current collectors are not necessarily reintroduced into the battery supply chain, and whether these materials are made back into battery components largely depends on supply-chain economics195. Vacuum distillation is increasingly being used to recover the organic solvents from the electrolyte and can produce battery-grade salts196,197,198. Additionally, the recycled electrolyte can be used to produce lithium salts. For example, LiF was obtained by exposing a LiPF6-based electrolyte to air, and Li2CO3 was produced by introducing Na2CO3 into a mixed electrolyte containing LiF, AlF3, CaF2 and other salts199,200. The recovery of LiPF6 from the electrolyte is still in an early phase and faces non-trivial barriers to commercial adoption, such as challenging economics and the propensity for by-product formation201. The binder, typically polyvinylidene fluoride, can be recovered from the spent electrode through a direct recycling process, which can prevent the formation of HF during the recycling process of electrode materials202. Finally, the separator can be recycled through washing with deionized water; the performance of the recovered separator is comparable to that of a commercial separator98.

Assessing the impact of battery recycling

The pursuit of innovations in battery recycling technologies within commercially viable routes and research to further advance direct recycling processes have different economic, environmental and social implications. Understanding the interconnected implications of battery recycling is important for developing effective and sustainable EOL strategies. In this section, we first outline the technical considerations associated with pyrometallurgical, hydrometallurgical and direct recycling approaches and then evaluate their economic, environmental and social implications, which is important for establishing a sustainable battery recycling cycle (Fig. 6).

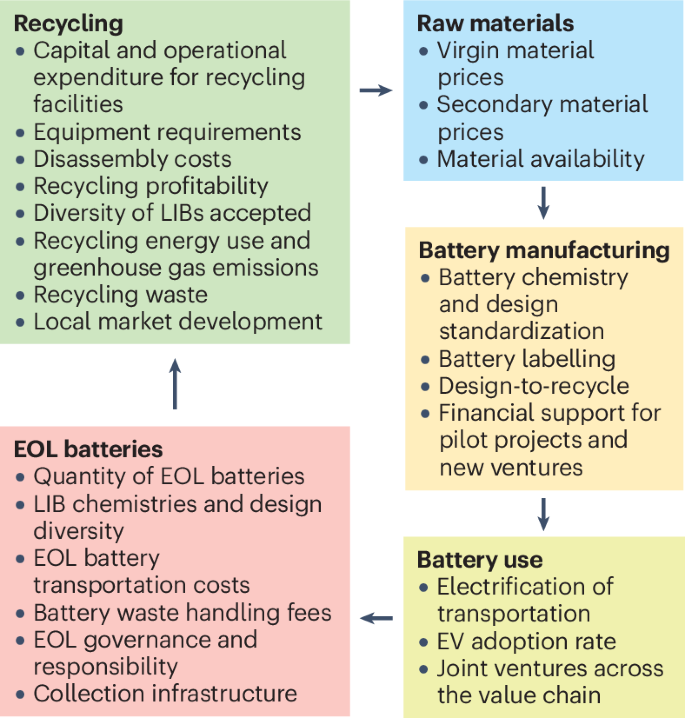

Technical, economic, environmental and social considerations throughout the lithium-ion battery (LIB) recycling cycle. The battery cycle is captured along five dimensions: raw materials, battery manufacturing, battery use, end-of-life (EOL) batteries and recycling. For raw materials, some of the relevant factors affecting recycling include the price of virgin and secondary materials as well as material availability. Battery manufacturing can impact recycling processes through battery chemistry and design choices, labelling, ease of processing and disassembly, and financial support for pilot projects and new manufacturing approaches. The degree of use of batteries affects the quantity and nature of EOL batteries, and is influenced by the electrification of transportation and electric vehicle (EV) adoption rates. Battery use within a region can foster joint ventures across the value chain. The collection of EOL batteries is affected by transportation costs, waste handling fees, collection infrastructure and classification of spent products, as well as governance and responsibility. The recycling process itself involves balancing capital and operational expenditure for recycling facilities, equipment requirements, disassembly costs, recycling profitability, diversity of LIBs accepted, energy use and emissions, recycling waste and local market development.

Technical considerations

Hydrometallurgical and pyrometallurgical processes, and more often combinations of the two, are currently being used in commercial-scale recycling facilities. Direct recycling has not been adopted on a commercial scale, although there are examples of it being used in laboratory environments and to recycle EOL battery cells203,204.

Pyrometallurgical recycling can accommodate a broad range of battery chemistries owing to the high temperatures used to smelt and extract valuable constituents205. Additionally, existing industry knowledge and infrastructure can be used to reduce the cost of pyrometallurgy. Companies already involved in mining, material refining or waste treatment can use their existing equipment and operational structure to recycle LIBs205,206. For example, sites with smelters can be used for pyrometallurgical processing of battery feedstock, reducing the fixed cost investment associated with beginning pyrometallurgical recycling207.

Despite the strengths of pyrometallurgical methods, hydrometallurgy-based methods are needed to obtain engineered products for cell manufacturing. Hydrometallurgy involves a complex series of unit operations in which processes of each facility are developed to treat a subset of LIB chemistries and form factors, and to maximize material recovery rates and profitability206. The scaling of hydrometallurgical processes is thus controlled by the need for specific chemistries as input. These processes use various leaching agents, including organic and inorganic acids, alkalis or bioleaching agents, followed by solvent extraction and precipitation. Hydrometallurgy has been increasingly used because it has a lower energy consumption than pyrometallurgy; however, it has limited flexibility in the chemicals that can be used for extraction and the pretreatment conditions208 owing to the high operational complexity, which arises from factors such as catalyst presence, constituent concentration, pH, temperature and composition.

Direct recycling involves manual disassembly and is thus characterized by labour and equipment requirements, which can be reduced by automatic disassembly or shredding and sorting209. Different processes are required to reconstitute different battery chemistries; therefore, direct recycling processes could either limit the range of LIBs that will be accepted and reduce facility and labour costs, or expand acceptance to include more diverse batteries as inputs and increase costs207. The direct recycling approach also requires that LIBs are in a good state to be recycled: for example, batteries should have minimal physical damage, intact electrodes and limited chemical degradation to enable the recovery and reuse of active materials with minimal reprocessing207. Furthermore, owing to the immature stage and long development period of automated disassembly technology, combined with the variability in battery designs, introducing automated disassembly in a direct recycling production line could make the process even harder to scale because the inputs will be limited to specific designs that are compatible with the production line design. However, in the long term, the application of automated disassembly technologies to direct recycling would be beneficial.

Economic implications

Recycling is often perceived as an unprofitable activity210. Before 2014, the market penetration of EVs was limited211; therefore, there are limited quantities of batteries currently reaching EOL and available for remanufacturing, repurposing or recycling relative to projected quantities. The main near-term source of feedstock for recycling facilities is manufacturing scrap from cell production. Combined with the high costs of transporting batteries, nascent companies involved in recycling have difficulties accessing enough volume to achieve economies of scale. However, EV car sales worldwide have grown from 6.6 million in 2021, to 10.2 million in 2022, and to 13.8 million in 2023, suggesting that in the future there will be a continuous supply of EOL batteries to provide a source of materials for secondary recovery1. The economic viability of recycling ventures is often challenged by the fluctuating, and occasionally low, prices of newly mined materials, as shaped by their ever-changing supply and demand dynamics, which can test the preference for secondary sources212. For example, following two years of increases, lithium spot prices decreased by 75% in 2023 and cobalt, nickel and graphite prices decreased by 30–45%213. The large capital expenditure required to start a recycling facility, as well as the uncertainty of EV adoption rates, can make investment in LIB recycling risky; thus, policies supporting new recycling ventures and the transition to EVs will be needed214.

Variations in material costs, energy input, operating labour, maintenance and local taxes make it difficult to compare recycling process using published economic case studies. Pyrometallurgy is often reported as the most expensive process based on the substantial capital investment associated with equipment required for high-temperature processing (although costs are low when existing equipment is used) as well as the large labour and utilities costs. Additionally, pyrometallurgical processes can have low material recovery rates because elements are released to the slag, where they are difficult to recover29. Hydrometallurgy is less expensive than pyrometallurgy although it does have high material costs214. The economic profitability of hydrometallurgy and pyrometallurgy has historically relied on their ability to extract the high concentrations of valuable cobalt present in spent LIBs. As cobalt concentrations in batteries decrease, direct recycling might become a preferable alternative210.

Direct recycling promises to be the cheapest of the three processes but widespread commercial demonstrations of direct recycling are still lacking210. The components recovered from direct recycling can be directly used in new LIBs; therefore, direct recycling theoretically yields the highest profit. For example, theoretical calculations suggest that direct recycling could achieve a profit of US$6.3 for 1 kg of spent NMC532 and graphite cells210. It is also important to note that disassembly costs associated with direct recycling can be a substantial contributor to the total recycling cost, especially in countries with high-cost labour, where it is estimated to reach >20% of the total recycling cost214.

Active battery material components can represent up to half of the cost of a LIB214. According to the EverBatt model, for commercial-level production of 50,000 t yr–1 of NMC111, materials obtained from pyrometallurgical recycling are 3% more expensive than virgin materials, whereas the materials obtained through the hydrometallurgical route are 5% cheaper136. Moreover, it was estimated that direct recycling would yield a 44% comparative cost advantage for producing 1 kg of NMC111 compared with using virgin raw materials136. However, in this calculation, costs for direct recycling were extrapolated from small-scale data because direct recycling has not yet been scaled to commercial levels. In addition, absolute and relative recycling costs are affected by various region- and facility-specific factors214 such as transportation, labour, utilities, general expenses and policy. Arguably, whether using recycled materials instead of virgin materials will reduce the cost of a battery pack is highly dependent on future supply and demand dynamics, including material availability, the cost of recycling processes and the effects of future policies on material prices. The potential economic benefits of recycling could become even more important as demand for EV batteries increases.

Environmental implications

Comparison of the environmental impact of different battery recycling methods relative to the use of virgin materials involves the consideration of numerous factors. For example, the environmental impact of a recycling technique could vary depending on the battery types, manufacturing scale and regional factors (such as water scarcity and carbon intensity of the grid). Additionally, system boundaries and baseline assumptions used to evaluate environmental impacts vary across reported analyses, making it difficult to compare results and identify universally optimal recycling methods.

Pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes have higher greenhouse gas emissions than direct methods209,210. Pyrometallurgical processes require high energy input205 owing to the high smelting temperature209,210. For example, the pyrometallurgical process requires an energy input 200% higher than the hydrometallurgical process to recycle 1 kg of NMC532 (ref. 210). Additionally, pyrometallurgical processes emit CO2 and HF, which must be treated to remove harmful components (for example, CO2 can be managed through carbon capture systems, whereas HF requires neutralization using scrubbers with alkaline solutions such as calcium hydroxide), and produces solid waste, which could contain residual toxic substances, including heavy metals, posing long-term environmental and health risks46,205,206. Although the hydrometallurgical process is less energy intensive than pyrometallurgy, the upstream manufacture of reagents and the need to purify the excess wastewater do make substantial contributions to the energy consumption of the process205,206,207,209. Organic acids have been proposed as alternatives to the inorganic ones widely used in hydrometallurgical processes; however, the high costs of organic acids prevent them from being adopted for recycling at industrial scales210. The energy cost of recycling 1 kg of spent LIBs with direct recycling is estimated to be 25% and 14% of that required by pyrometallurgical or hydrometallurgical recycling, respectively210. Additionally, direct recycling produces approximately 20% of the total greenhouse gas emissions produced by pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical recycling process, respectively210. Direct recycling can also reduce the production of waste and low-value by-products, and it has lower consumption of chemicals than pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes210.

Most recycling methods report lower greenhouse gas emissions than the use of mined materials; however, the different assumptions made in assessments of these emissions makes such comparisons challenging. Argonne’s GREET life-cycle analysis model suggests that if 80%, 95% and 95% of the lithium, cobalt and nickel, respectively, used in the production of a NMC111-based battery were secondary hydrometallurgical recovered materials, greenhouse gas emissions could be reduced by 26% relative to 100% mined materials215. The same model calculates that if 95% of the cobalt and nickel used were products of pyrometallurgical recycling (but with no recovered lithium being used), greenhouse gas emissions could be reduced by 6%215. If direct recycling can recover 95% of the cathode material, it could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 50%215, but this technique is not yet ready to be used at industrial scales, and further advances are needed. Using life-cycle assessments216 to account for the broader implications of reducing the use of primary extracted materials, leads to an 85% increase in ecological benefits calculated for hydrometallurgical processing and direct recycling over conventional approaches217.

Broader implications

Whether a recycling network will be profitable largely depends on the cost of transporting spent LIBs. Thus, it is helpful to establish recycling chain hubs within a country or region214. The resulting regionalization of supply chains presents an economic opportunity for local market development. Therefore, governments have strong motives to promote the growth of battery recycling within their regions212, even if the region was not previously involved in battery-related activities. Recycling also strengthens supply chain security for materials used in battery manufacturing because it can reduce reliance on imports and mitigate global disruptions. Regional recycling hubs create stable material flows, support local industries, simplify logistics and enhance national supply-chain resilience212. However, achieving these benefits requires supportive policies and regulations to address the complexities of battery recycling.

The development of recycling networks can be supported by interventions such as funding research across the value chain to improve recycling technologies for diverse batteries, promoting recycling-conscious battery design, optimizing the cost and efficiency of manufacturing and logistics, and providing financial support for pilot projects and incentives for companies to enter the recycling sector212,214. Promoting joint ventures between economic actors across the value chain can also develop synergies for a closed-loop economy205. Clear governance is needed to increase LIB collection rates and streamline their EOL management205,212; for example, attributing responsibility for managing spent batteries to producers, establishing a battery tracking system, and investing in collection infrastructure. Policy interventions to standardize the design of battery packs to make them easier to disassemble will enable more streamlined and safer recycling while reducing disassembly costs205,212,214,215. Additionally, requiring manufacturers to label battery chemistries will simplify the sorting process, aid safe and efficient recycling by various stakeholders, and increase transparency across the value chain205,207,210,212,218. Such interventions must be paired with policies promoting the electrification of transportation in general, so that the necessary input for recycling ventures becomes available214.

Summary and future perspectives

This Review presents various recycling technologies, many of which are starting to be demonstrated at scale and are having a tangible impact on the nascent battery ecosystem. Pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical recycling methods have been commercialized, whereas direct recycling and upcycling are at laboratory or pilot scale46,219. The high efficiency, low energy costs, high recycling rates, and economic and environmental benefits of hydrometallurgical recycling make it preferable to pyrometallurgical recycling. Although direct recycling seems to be an ideal solution with the highest recovery efficiency and purity, it is constrained by strict pretreatment steps, the production of outdated products and manual processes. Despite these drawbacks, direct recycling might first be commercialized for recycling scrap from battery manufacturing processes, in which the feedstock would represent a single and relevant chemistry. Advanced recycling technologies220, such as hydrometallurgy-based upcycling, are starting to be commercially adopted, which could further drive advances and encourage continued research efforts.