The “Future of Energy”? Building resilience to ExxonMobil’s disinformation through disclosures and inoculation

Introduction

On June 24, 2024, Secretary-General António Guterres launched the United Nations Global Principles for Information Integrity. In so doing, Guterres highlighted the climate crisis as a particular area of concern, stating, “Coordinated disinformation campaigns are seeking to undermine climate action.” He urged advertisers and public relations practitioners to refrain from greenwashing and to avoid clients that are “misleading people and destroying our planet”1. Yet, sustained disinformation campaigns – intentionally inaccurate content designed to mislead2 – on social media in Brazil, for example, have been criticized for being “rampant,” “ardent,” and “troubling” for condoning, and then perpetuating, renewed deforestation of the Amazon rainforest3,4. Disinformation has also included patently false conspiracy theories such as Chemtrails – the notion that condensation trails left in the sky by aircraft consist of chemical agents sprayed for nefarious purposes – which up to 40% of Americans believe as “somewhat true,” thereby influencing public attitudes about climate policy and geoengineering5. As one study concluded when noting these trends, “disinformation represents one of the major obstacles to meaningful actions against climate change skepticism.”6

Coordinated disinformation campaigns about climate change have pernicious and long-lasting negative impacts on sustainability patterns or beliefs about climate change. The effects of climate disinformation include increasing political polarization and/or political inaction and slowing down or even rejecting climate policies, making how one responds to and communicates about climate action a deeply political process7,8,9,10. Such effects can be countered by selecting the right communication tools when operating in an adversarial environment such as using well-designed forewarning messages to counter disinformation11. This study specifically focuses on disclosure messages and contextualized inoculation strategies to counter clean energy transition disinformation campaigns by big oil companies.

Disinformation campaigns often reflect the intent of well-funded vested interest groups that benefit from marginalizing environmental issues such as climate change12,13. Recently published archival research suggests that the American Petroleum Institute was “promulgating false and misleading information about climate change” as early as 198014. Internal projections created by ExxonMobil starting in the late 1970s and 1980s on the impact of fossil fuels on climate change were very accurate, even surpassing those of some academic and governmental scientists; yet the firm continued to actively manufacture doubt about the certainty of climate science15. Moreover, since the 1970s, when mainstream news organizations such as the New York Times and the Washington Post launched their paid editorials – or advertorials – they have been instrumental to fossil fuel companies in helping to shape how the public and policy makers perceive the oil industry and its contributions to society16,17. This has a downstream effect towards potential greenwashing where the entire information ecosystem can be manipulated to convey a specific narrative. For example, a recent study found that big oil firms engage in redirecting and reframing social media communications on climate and sustainability when nudged by intergovernmental and non-governmental stakeholders18. Similarly, another study found that fossil firms’ investment portfolios frequently do not match their climate and clean energy discourse which is often linked to greenwashing behavior19.

In this study, we contribute to a growing body of research into how to mitigate the potentially misleading effects of a covert type of advertising called native advertising20,21. While scholars have examined the effectiveness of disclosures (i.e., labels) that reveal to the consumer that the content they are reading/viewing is paid advertising, thereby increasing consumers’ understanding of the content’s origins, native advertising by fossil fuel companies, or about climate change, has not yet received scholarly attention. Another line of scholarship draws on inoculation theory22 to advance the idea of forewarning messages – or prebunking23,24 – to warn the consumer about potential exposure to paid content that may be misleading. In the present study, we investigate the impacts these two mitigation strategies, i.e., disclosure and forewarning messages, have on reducing people’s misperceptions after exposure to a native advertising post from the fossil fuel industry. We term our study the “Future of Energy” for two reasons. Firstly, it refers to a real-world advertising campaign sponsored by ExxonMobil, one on which we based our online experiment. Secondly, however, is its double meaning as a new technique energy companies use to manipulate mass public opinion, in this case relying on misinformation to shape social attitudes, one that we worry could also become common in the future strategies of firms and other actors intent on misleading the public.

In the last fifteen years, news organizations have developed a digital version of advertorials—native advertising—to offer to advertisers. These have been adopted by the fossil fuel industry, among others, to influence public attitudes about their businesses. Native advertising refers to paid content that is created and published, mostly online, by an assortment of news media, from legacy outlets such as the New York Times and the Washington Post to internet era companies like Politico and Huffington Post. What distinguishes native advertising from traditional advertising is its deliberate design—with visual cues of format, font, headings, and masthead—that mimics the news organization’s own journalistic reporting and other content. Whereas the advertorials of the analog era were created by public relations and advertising agencies and then disseminated by news outlets, today many news organizations operate their own in-house content studios, separate from their newsrooms, to create native advertising on behalf of corporate and other paying clients. These in-house content studios perform all the functions of a traditional advertising agency but from within the confines of the news organization itself. Thus, native advertising enables news outlets to generate revenue not only from the distribution of a client’s message, but also from creating the message in a way that mimics its reporting25.

Although the incremental revenue generated by native advertising is sorely needed at a time when the journalism industry has suffered financially from technological evolutions in the media environment, many critics have raised concerns about negative effects of native ads. For example, even though the US Federal Trade Commission requires disclosures that clearly and conspicuously distinguish native advertising from news articles, academic research has repeatedly shown that most media consumers do not notice the disclosures or do not understand what they mean and are therefore often deceived by the content, believing it to be news25,26,27. Studies have also demonstrated that the disclosures, more often than not, disappear when native advertising is posted on social media, making it seem like a journalistic article is being shared rather than commercial content28,29. Moreover, other evidence reveals that the claims in native advertising created by a news outlet can sometimes contradict the reporting coming from the newsroom30.

Thus, the fossil fuel industry’s history of deceptive communications, combined with the nebulous properties and negative effects of native advertising, give good reasons for concern that companies may use native ads to further fuel climate skepticism and delay climate action. In other words, we are concerned that native advertising may be a potent form of disinformation—one living at the heart of our fact-based communication system: the mainstream news media.

Efforts to reduce the harms of the fossil fuel industry’s disinformation campaigns exist among numerous research programs into how to mitigate false and misleading content in a digital and polluted information environment. A growing body of evidence has emerged examining the extent to which interventions can succeed in refuting disinformation. Given that disinformation is often “sticky” and difficult to correct, best practices call for preemptive interventions31. Premised on inoculation theory, these “pre-bunking” interventions build up psychological immunity against attempts at influence in a way analogous to immunization against biological pathogens32. However, rather than injecting a weakened virus, people are exposed to a weakened message designed to promote immunity against forthcoming influence attempts33. For instance, forewarnings about the strategic use of native advertising have significantly decreased the likelihood that people are deceived by it20,34.

Although some recent research has raised doubt about the effectiveness of inoculation strategies35, the preponderance of evidence over the decades has shown that prebunking is widely effective across a variety of topics – including climate disinformation – and across varying cultures36,37,38. Yet, despite the promise of inoculation messages, studies have noted that their effects decay over time and therefore require reinforcement messaging39. There is also conflicting evidence about the scalability of inoculation messages. While some studies indicate messages are scalable on social media40 and can even be contagious, spreading between individuals28, other research suggests motivational obstacles hinder widespread acceptance of inoculation messages41. Moreover, some studies indicate that although inoculation messages reduce belief in disinformation, they may also make people skeptical of all evidence including true information42. Given that previous studies have found resistance to misinformation can be induced by cognitively inoculating individuals against doubt-sowing about climate change43,44, we look to extend this research to energy-related disinformation specifically being spread by ExxonMobil. In particular, the present study aims to test the effects of native advertising disclosures and prebunking messages in building cognitive resilience to disinformation efforts, such as The Future of Energy ad.

The above sections have noted the large trove of evidence that has accrued regarding the false and misleading communications from the fossil fuel industry; the body of work documenting native advertising and its misleading effects; and the research programs that have developed strategies for limiting the effects of misinformation among the public. The present study is the first to bring these three important strains of research together: to investigate how two mitigation strategies may reduce climate misperceptions caused by exposure to native advertising.

Recent evidence reveals that big oil and gas firms like ExxonMobil had credible internal scientific knowledge on par with independent scientists and government institutions of the causes and consequences of climate change. While scientists worked to communicate what they knew about the impact of fossil fuel emissions on climate change, ExxonMobil acted to deny it—including overemphasizing uncertainties, denigrating climate models, mythologizing global cooling, creating ignorance about the discernibility of anthropogenic warming through specific rhetoric, and staying silent about the possibility of stranded fossil fuel assets in a low-carbon world15. In the clean energy transition context, rhetorical instruments – like native advertisements – are being used to reframe and reiterate climate and sustainability communications from stakeholders that hold ExxonMobil accountable18, making it urgent to assess how native ads on behalf of big oil giants influence climate perceptions and how to design appropriate intervention strategies against this practice.

Our experiment is designed around a real native ad, titled “The Future of Energy,” which was sponsored by ExxonMobil and appeared on the New York Times website beginning in 2018. It was created by T Brand Studio, the Times’ in-house design studio, as part of its “Unexpected Energy” campaign for which the news outlet was paid $5 million by ExxonMobil (Fig. 1)45. The ad is a classic native advertisement, with the Times’ masthead logo prominently top and center, the “paid post” disclosure below it, and ExxonMobil’s (relatively small but red) logo in the top left. As the viewer scrolls through the webpage’s high production-value visuals, they read not about ExxonMobil’s oil pumping or refining, but algae ponds in Southern California, and Exxon’s efforts to “create the next generation of biofuels.” The page is scattered with infographics representing algae, green technology and a healthy Earth. “We’re working to decrease our overall carbon footprint,” an Exxon researcher explains46.

ExxonMobil’s “Future of Energy” misleading native advertisement created by the New York Times T-Brand Studio.

To explain the misleading nature of the ad, we turn to lawsuits brought against Exxon by multiple states that have cited the ad specifically as an example of misleading communications about climate change and Exxon’s business practices. The Massachusetts lawsuit states, “ExxonMobil is running a series of paid full-page ads in print editions and posts in the electronic edition of The New York Times, produced with The New York Times’ T Brand Studio, in which ExxonMobil misleadingly gushes about its efforts to develop energy production from alternate sources like algae and plant waste, efforts that pale in comparison to the investment ExxonMobil continues to make in fossil fuel production.”47

Then-Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey charged the ad with being “false and misleading” and in violation of the Massachusetts Consumer Protection Act. Even where it was presumably accurate it was misleading: an algae researcher states, “we’re aiming to have the technical ability to produce 10,000 barrels of algae-based biofuel a day by 2025.” But even if this were true, “the ad does not mention that the goal only equates to 0.2 percent of the corporation’s current refinery capacity, nor does it note Exxon’s plans for fossil fuel production in the years to come.”48 In the end, the project produced no fuel at all: in 2023 Exxon announced it was ending its investments in algae as a source of energy49. Yet as of this writing, the native ad is still accessible on the Times’ website.

Results

Our results indicate that participants exposed to the “Future of Energy” advertisement with the disclosure reported directionally, but not significantly, higher levels of agreement [t(963) = −1.53, p < 0.063 one-tailed, d = −0.10] that the purpose of the post was to promote the ExxonMobil brand (M = 5.81, SD = 1.70) compared to participants who did not see a disclosure (M = 5.64, SD = 1.67). However, participants largely found the social media post to be promotional in nature even without a disclosure. Examining the results of an ANOVA that accounts for both exposure to a disclosure and an inoculation message indicate no significant effects on the perceived commercial nature of the post [F(2, 1074) = 1.91, p = 0.149, adj. R2 = 0.002].

While the perceived promotional nature of a social media post does not necessarily indicate it was considered advertising, a more sensitive measure is the dichotomous variable asking participants if they saw any advertising in/around the post. Almost half of the people exposed to a disclosure indicated that they noticed advertising (49.5%) compared to only 22.3% of those who were not exposed to a disclosure, a significant difference [χ2(1, 970) = 78.08, p < 0.001]. However, consistent with the previous measure, exposure to a disclosure revealed no significant differences in ad recognition (z = 0.931, p = 0.176) whether combined with an inoculation message (48% recognition) or not (53% recognition).

To examine how exposure to the “Future of Energy” ad influenced brand perceptions, a MANCOVA was conducted among participants exposed to the social media post generated from sharing the native advertisement as well as among those in the control group who were exposed to a post reviewing a restaurant. A dummy variable was computed to control for exposure to a native advertising disclosure (0 = no, 1 = yes). Comparisons were made between participants who were not exposed to an inoculation message, those who were exposed to an inoculation message, and those in the control group on multiple outcome variables. For the measure on the generalized perceived accuracy of the claims in the posts, there was a significant difference between groups [F(3, 1148) = 11.17, p < 0.001, adj. R2 = 0.026]. Pairwise comparisons reveal that participants in the control group reported significantly higher levels of perceived accuracy of the claims in the post (M = 4.46, SE = 0.15) than did those in the no inoculation message group (M = 4.02, SE = 0.07, p = 0.009) and compared to those in the any inoculation message group (M = 3.74, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001). Moreover, participants in the no inoculation group perceived the content of the post to be significantly more accurate than those exposed to any inoculation message (p < 0.001). Exposure to an advertising disclosure had no bearing on these effects (p = 0.138).

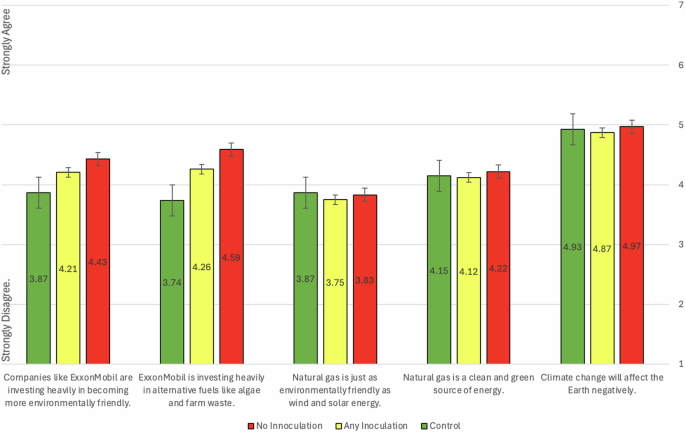

We also asked participants how much they agreed with specific claims made in the “Future of Energy” post. For the misleading claim “companies like ExxonMobil are investing heavily in becoming more environmentally friendly,” there was a significant difference between groups [F(3, 1148) = 3.01, p =0.029, adj. R2 = .005]. Pairwise comparisons reveal that participants who were not exposed to an inoculation message (see Fig. 2 and Table 1) reported significantly stronger agreement with this claim than were those exposed to an inoculation message (p = 0.043) and those in the control group (p = 0.005). There was no statistical difference between those exposed to an inoculation message and those in the control group (p = 0.064), indicating that the effects of exposure to the native advertisement were completely mitigated by the inoculation message to the same level as those never exposed to the ad. Exposure to an advertising disclosure had no influence on these effects (p = 0.494).

Source: Authors. Note. Mean agreement by group with 95% confidence intervals.

A similar, but not identical, pattern was observed for the misleading claim that “ExxonMobil is investing heavily in alternative fuels like algae and farm waste” [F(3, 1148) = 7.14, p < 0.001, adj. R2 = 0.016]. Pairwise comparisons reveal that participants who were not exposed to an inoculation message (see Fig. 2 and Table 1) reported significantly stronger agreement with this claim than those exposed to an inoculation message (p = 0.002) and those in the control group (p < 0.001). Moreover, those who were exposed to an inoculation message reported stronger agreement with the claim than those in the control group (p = 0.006), suggesting that while the inoculation message offered some protection, it did not completely mitigate the influence of this claim. At the same time, exposure to the advertising disclosure was also significant in contributing to a reduction in agreement with this claim (p = 0.035).

For contrast, we also asked participants their agreement with misleading claims that were not mentioned in the “Future of Energy” post. As shown in Fig. 4 and Table 1, there were no differences between groups with either of the claims, “Natural gas is just as environmentally friendly as wind and solar energy” [F(3, 1148) = 0.31, p = 0.816, adj. R2 = −0.002] or “Natural gas is a clean and green source of energy” [F(3, 1148) = 0.76, p = 0.519, adj. R2 = −0.001]. Exposure to the advertising disclosure had no effect on perceptions of either the former (p = 0.584) or latter (p = 0.236) claim.

To examine whether inoculation messages reduce belief in true claims, an ANCOVA was conducted to compare each group’s agreement with the true statement, “climate change will affect the Earth negatively.” Because this item was measured after some participants were exposed to a correction message, two covariates were introduced in this model: exposure to a disclosure label and exposure to a correction message (As part of a larger study, some participants were exposed to an additional social media post that included a comment which served as a correction of the disinformation. Because the corrections are not germane to the present study, they are not reported further and serve as a covariate for this analysis). The analysis reveals no differences between the three groups [F(4, 1150) = 0.37, p = 0.832, adj. R2 = −0.002] indicating that while exposure to an inoculation message reduced belief in disinformation, it did not decrease belief in an accurate climate claim (see Fig. 4 and Table 1). Exposure to neither the advertising disclosure (p = 0.349) nor a correction message (p = 0.904) affected perceptions.

Discussion

ExxonMobil’s “Future of Energy” advertisement was effective at influencing beliefs, but disclosures and inoculation messaging provided some mitigation. Participants exposed to the native ad in a simulated social media post were more likely to believe the claims it presented but not unrelated climate disinformation. This suggests even a single exposure to misleading climate claims can shape beliefs. Disclosures helped some participants recognize the ad as advertising, but many remained unaware of the disclosure or its significance, as shown in prior studies50,51. Crucially, inoculation messaging proved more effective than disclosures at reducing susceptibility to misleading claims. Our findings indicate that disclosures and inoculation messages worked together to reduce belief in the specific claim that “ExxonMobil is investing heavily in alternative fuels like algae and farm waste.” However, disclosures alone had no impact on the broader impression – or gist – created by the ad, as in the claim that “companies like ExxonMobil are investing heavily in becoming more environmentally friendly.” Since general impressions are more memorable and widely shared than specific details, this is concerning52. Moreover, disclosures often vanish when native ads are shared on social media, limiting their utility29,53. Overall, while disclosures aid in identifying native advertising, inoculation messaging is key to building psychological resilience against disinformation.

Given that fossil fuel companies are pouring tens of millions of dollars into native advertisements that are, by design, deceptive, we should be concerned54. Congressional discovery has already uncovered that ExxonMobil’s own research into the results of the “Unexpected Energy” campaign indicated public perceptions were affected and became more favorable toward the company55. As lawsuits against the fossil fuel industry wind their way through the legal system in seeking to hold these companies accountable for their disinformation efforts, this study provides additional independent evidence demonstrating a causal link between ExxonMobil’s native advertising claims and how consumers perceive the company’s climate-related actions56.

Moreover, because news organizations have repeatedly failed to ensure that disclosures remain attached to native advertisements regardless of where the content appears, other measures must be taken to foster recognition among the public of commercial content disguised as news. The results of this study indicate that inoculation messages are one such intervention measure that offers promise for improving public resiliency to disinformation efforts previously practiced by the fossil fuel industry. In some cases, a forewarning message effectively mitigated the influence of the disinformation. In other cases, the forewarning message minimized but did not entirely counteract the influence of the native advertisement. These results also indicate that the inoculation was effective without making participants more skeptical of true claims about climate. Future research is warranted on how these types of inoculation messages can be effectively scaled.

As with any research effort, we must acknowledge certain limitations to these findings. This study tested the effects of a single advertising message, ExxonMobil’s “The Future of Energy” ad. Although this ad is well-justified given its prominence as an example of harmful native advertising, we acknowledge there may be idiosyncrasies inherent in the ad preventing the findings from generalizing to other ads. Yet, according to investigative reporting, this ExxonMobil ad is part and parcel of a common practice extending across the fossil fuel industry including ads from BP, Chevron, Equinor, Saudi Aramco, Shell and the industry lobby group, the American Petroleum Institute (API), many of which are similarly misleading, if not outright false. According to Geoffrey Supran, a University of Miami researcher who studies the history of climate disinformation and propaganda by fossil fuel interests, increasingly “Big Oil and mainstream media [are] collaborating in PR campaigns for the industry”30,57,58. Nonetheless, future research should test the effects of multiple ads.

It is also worth considering that although this study is based upon a real native advertisement created by a leading news outlet for a multinational oil company, the forced exposure necessitated by an online experiment is somewhat contrived. How people respond to such an advertisement “in the wild,” so to speak, may be different. Yet, some of the positive effects of disclosures are consistent with those from field research28. Moreover, audiences are not monolithic. Recent research has indicated that some people are more susceptible to disinformation than others59. Investigating the degree to which disclosures and inoculation messages are effective with those who are more and less susceptible to disinformation merits scrutiny.

As the fossil fuel industry continues to spread disinformation throughout media platforms around the globe, an institution positioned as a bulwark to this threat—the news media—has been an accomplice. Although the financial realities of the current news media environment have necessitated that news organizations pivot to finding alternate revenue streams such as native advertising, studies such as this one shed light onto the pitfalls associated with independent and presumably unbiased news organizations legitimizing content from entities such as ExxonMobil without adequate disclosures. Such practices only serve to create content confusion, amplify fossil fuel companies’ greenwashing narratives, and further fuel public distrust in mainstream news media. Studies like ours, offering emergent evidence on how to counter climate disinformation through disclosures and inoculation, provide a much needed first defense against such discursive incursions, facilitating a critical step towards communication-led climate action.

Methods

“The Future of Energy” ad is a useful case for examining native advertising by fossil fuel companies about issues of climate and corporate actions to improve their environmental record, as well as the effectiveness of messages designed to mitigate its misleading effects. In our experiment, we exposed respondents to an image of the actual “Future of Energy” ad as it appeared when shared on Facebook. We chose a social media format for our stimuli because not only are news organizations hired to create native ads that resemble their editorial content, but they are often contractually obligated to amplify these ads via social media, as well60. As such, we conducted a 2 (inoculation message: yes/no) by 2 (native advertising disclosure: yes/no) between subjects experiment with an offset control condition and measured effects on a set of beliefs about the nature of climate change and whether corporations were doing enough to reduce their climate impacts.

Experimental conditions and stimuli

Participants were randomly assigned to one of 5 (2 × 2 + 1) experimental conditions (see Table 2) as follows.

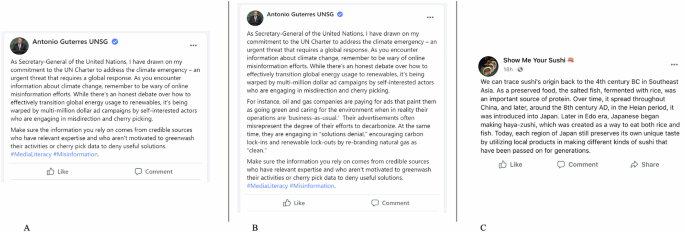

Inoculation vs. no inoculation/control: Those in the inoculation conditions saw a fictitious social media post that appeared to be from United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres reminding people to be wary of online misinformation efforts (see Fig. 3A, B) (Although this study was fielded in the spring of 2023, a year later Secretary General Guterres released a similar statement.)1. Designed to psychologically inoculate people from influence, these messages forewarned participants about the techniques and facts being used in advertising campaigns by self-interested actors33. Participants in the no inoculation and control conditions instead saw a different made-up post about the origins of sushi modified from other inoculation studies (see Fig. 3C)61,62.

A shows the technique-based inoculation. B shows the fact-based inoculation message (Note: As part of a larger study, two different inoculation messages were utilized: technique-based and fact-based messages33. Although both messages were equally effective in reducing susceptibility to influence, given that the differing inoculation strategies are beyond the scope of the present study, the conditions were collapsed and a dummy variable was computed as a covariate). C shows the control/no inoculation message given to some respondents.

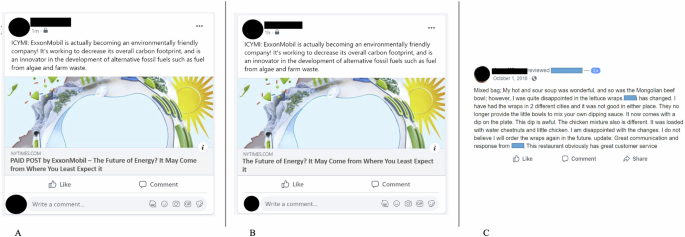

Disclosure vs. no disclosure: Some participants then saw a second social media post in which the author shared the actual “Future of Energy” native advertisement from the New York Times with added commentary claiming that ExxonMobil is becoming an environmentally friendly company due to its investments in renewable energy noted in the ad. In some conditions, the shared story included a disclosure indicating it was a “Paid Post by ExxonMobil,” the New York Times’ designation for native advertising (see Fig. 4A). In the no disclosure conditions, this label was missing (see Fig. 4B).

A shows the native advertisement with the disclosure, B without. C Shows the control message given to some respondents.

Control: In the control condition, the social media post was of a restaurant review (see Fig. 4C). In all but the inoculation and sushi conditions, the source of the social media post was obscured to avoid source effects.

Sample and procedure

After Institutional Review Board approval, a self-administered online survey was fielded May 30 – June 21, 2023, by YouGov, an international organization recognized for its social-scientific research. Eligibility for the study included those aged 18+ residing in the US and able to read English. Using YouGov’s “sample matching” approach, a random probability sample was estimated from its opt-in online population using propensity scores derived from gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, and region. The data were post-stratified on the 2016 and 2020 US presidential vote choice and a four-way stratification of age, education, gender, and race to produce a nationally representative weighting scheme.

Among the sample of 1045 participants, the average age was 49 (SD = 17.66), 51% identified as a woman, 43% were married, 62% identified as white, 17% as Hispanic, and 12% as Black, 33% had a high school diploma as their highest level of education while 23% had a bachelor’s degree. Political party affiliation was 35% Democrat, 27% Independent, and 25% Republican. Political ideology (M = 3.00, SD = 1.21) was measured on a five-point scale (1 = very liberal, 5 = very conservative).

Participants were invited to respond to a survey (median length = 40.63 min) about media habits and perceptions (see Appendix A). Following informed consent, respondents were randomly assigned to one of the treatment or control conditions and were asked about their media and information consumption habits as well as their knowledge and perceptions on a variety of topics (e.g., politics, climate, GMOs, immigration, gun control, vaccines). They were then told to imagine that they had logged in to their social media account and were presented with a message at the top of their newsfeed which they were asked to read carefully and then share their perceptions. This was followed by a second post about which participants were again asked to share their perceptions. In both cases, participants were allowed to view the posts for as long or short as they desired. However, once they proceeded past the stimuli to answer the perception questions, they were unable to return to the stimuli for further viewing. Following demographic questions, participants were debriefed and compensated by YouGov with points that could accumulate for nominal rewards such as T-shirts, tote bags, or prepaid gift cards63.

Measures

Ad recognition

To determine whether participants recognized the content from the second social media post was a native advertisement, two measures were examined. One measure used a 7-point Likert scale to indicate agreement that the purpose of the social media post was to “advertise/promote the ExxonMobil brand” where 1=strongly disagree and 7=strongly agree (M = 5.49, SD = 1.92)64. Another measure was a dichotomous variable asking participants whether they noticed any advertising in/around the social media post they saw (no=64%, yes=36%)26.

Disinformation belief

Several measures of disinformation belief were gauged. As an assessment of the social media post in aggregate, the perceived accuracy of claims overall was measured by asking “How accurate do you think the author’s claim is in the social media post?” using a 7 point, Likert-type scale where 1=very inaccurate and 7=very accurate (M = 3.89, SD = 1.33). In addition, belief in four specific claims were measured using a 7-point Likert scale where 1=strongly disagree and 7=strongly agree. Claim 1: “Companies like ExxonMobil are investing heavily in becoming more environmentally friendly” (M = 4.27, SD = 1.68). Claim 2: “ExxonMobil is investing heavily in alternative fuels like algae and farm waste” (M = 4.35, SD = 1.66). Claim 3: “Natural gas is just as environmentally friendly as wind and solar energy” (M = 3.79, SD = 1.90). Claim 4: “Natural gas is a clean and green source of energy” (M = 4.17, SD = 1.79).

Accurate information belief

This was measured using a 7-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree with regard to the claim, “climate change will affect the Earth negatively” (M = 4.94, SD = 2.03).

Responses