The gender-sex incongruence is partly a mind–body incongruence

Introduction

Sex and gender are strange bedfellows. Sex is defined by a person’s body—their anatomy, genetics, and hormones; gender, on the other hand, is a mental construct that captures a person’s identity. While sex and gender are closely aligned in cisgender people, they diverge in transgender people—individuals who experience their gender as distinct from their natal gender, assigned based on their sex1. What psychological processes are involved in the sex-gender incongruence in transgender people? And what effects might result for the psyche?

These questions are significant because a person’s gender is core to their identity. Rejecting the gender of a transgender person thus denies their identity, undermines their inalienable rights to dignity2, and inflicts psychological pain that puts them at risk for self-harm and suicidality3,4,5. Yet many American adults question the gender-sex distinction6. They maintain that a person’s gender is determined by the sex assigned to them at birth, that public gender attitudes are changing too quickly, and some view the focus on transgender issues as a social trend—a fad7.

This view rests on a tacit psychological assumption. Gender transitioning, so that logic goes, is psychologically superficial, transitory, and inconsequential. Accordingly, beyond matters of sex and gender, one would not expect transgender and cisgender people to show any systematic psychological differences. And if transgender identity is only skin-deep, psychologically, then transgender identity would not be germane to a person’s identity and dignity, and as such, it would not seem to merit the moral and legal protection afforded by society.

Our present results challenge this psychological assumption. We demonstrate that transgender people exhibit profound psychological differences (compared to cisgender people). Going far beyond the sex-gender distinction, these differences concern tacit fundamental beliefs about who we are as humans—minds or bodies.

Mind–body intuitions are consequential, tacit, and variable

At first blush, the mind–body question seems strictly philosophical, devoid of relevance to psychology. But a large literature shows that concerns with bodies and minds are central to the human psyche and very much evident in laypeople—adults and children8,9,10,11,12, and members of large- and small-scale societies13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

People perceive the mind as ethereal, distinct from the body. These attitudes are mostly tacit—they apply without explicit conscious awareness, “under the hood”. Nonetheless, people tacitly separate minds and bodies even when they consciously assert just the contrary, and even when effortful deliberation is blocked by cognitive load22,23. Moreover, the separation of minds and bodies has broad impacts on cognition—it has been shown to influence reasoning on neuroscience24 criminal justice25,26,27,28,29, free will30,31, and psychiatric disorders32,33,34.

Bodies, in laypeople’s view, are physical entities—they are solid (like objects), and they are affected by physical causes (e.g., force) and biological processes (e.g., disease). Minds, by contrast, do not seem physical. And indeed, people believe minds can violate physical laws: minds can emerge in the “wrong body” (e.g., that of another person) or in no body at all (e.g., in ghost, gods and spirits)8,35,36. So, as we intuitively reason about ourselves and others, we interpret their actions in two conflicting modes—physical vs. mental. For instance, if people attribute depression to the mind (a “mental disorder”), they conclude it can be alleviated by psychotherapy, but if they ascribe it to the body (“a brain disorder”), they favor a psychotropic approach37. These two modes of reasoning compete, and their incongruence can elicit observable tension38.

Recent research suggests that the strength of these mind–body tensions can vary among individuals. For example, autistic people show weaker mind–body separation than neurotypicals39, and neurotypical males show weaker separation than females40. These individual differences likely arise because the mind–body separation is linked to mindreading abilities8. Because autistic people show weaker mindreading (relative to neurotypicals41), as do males (relative to females)42, these groups are expected to show weaker mind–body separation, just as observed. These variations in the perception of the mind–body divide set the stage for asking whether transgender and cisgender individuals might differ on the strength of their mind–body intuitions.

Is the sex-gender incongruence linked to a mind–body tension?

The question arises because, as noted, transgender individuals experience an incongruence between their perceived gender and the one assigned to them at birth. Perceived gender, by definition, is a psychological, mental construct, whereas birth-assigned gender is determined by one’s body (typically, anatomy). An incongruence between sex and gender (in transgender people) could potentially reflect a stronger separation between mind and body, generally.

Such a stronger mind–body separation could, in principle, reflect either a cause of transgender identity or a consequence. One possibility is that transgender people are inherently prone to separate mind–body more strongly (for either cognitive or other reasons), and this stronger mind–body separation is among the causes of transgender identity. Alternatively, the mind–body separation could be a consequence of the life experience of transgender people. As a transgender person goes through significant life changes to their body, suggesting to them that I remain me, even when my body changes, they might tacitly conclude that I am not my body.

Critically, regardless of whether the mind–body separation is a cause or consequence of transgender identity, this mindset ought to shape one’s perception of bodies and minds—the prism in which people intuitively construe their view of themselves and others. If such differences exist, then their psychological consequences might be quite profound, extending far beyond gender identity per se. Here, we seek to explore whether transgender people show a stronger mind–body separation than cisgender individuals. The question of why they do so (as a cause of their transgender identity or a consequence) falls beyond the scope of this inquiry.

Because the question of mind–body links and transgender identity are often fraught with controversy, a few words of clarification are in order. Mind–body intuitions—the topic of this research—strictly concern how a person perceives the link between bodies and minds, rather than what minds and bodies really are (a topic of much debate in philosophy). By asking whether transgender people perceive minds as more distinct from bodies, we by no means assert that their minds and bodies are distinct, and we certainly do not question whether they ought to be viewed as such. Our goal, then, is strictly descriptive: we seek to characterize the reasoning of transgender individuals about mind and body and link it to their gender identity.

Gauging mind–body intuitions

If people view the mind as distinct from the body, then they ought to conclude that body and mind are dissociable. Maintaining one’s body does not ensure that the mind persists, whereas obliterating one’s body could still allow for the mind to flourish (in the afterlife).

To gauge the mind–body separation, we invited people to reason about imaginary scenarios describing some transformation of a person. Some of these transformations explicitly maintain a person’s body, whereas others do not. For instance, one of the scenarios—body replication—creates a replica of every aspect of a human’s body. As such, this scenario explicitly preserves the body but not necessarily the mind. Other scenarios change or obliterate the body. For instance, the afterlife scenario entails the withering of the body but potentially maintains the mind (and participants are instructed to assume the afterlife exists).

If a person separates minds and bodies, then they ought to expect a person’s mind to persist in the afterlife (without the body), but not necessarily in the body-replication scenario (when it is only the body that is explicitly preserved). And if transgender participants show a stronger mind–body separation, then transgender people ought to show a stronger difference between these two scenarios relative to cisgender participants. Experiment 1 tests these predictions.

Experiment 2 examines an imaginary “body-swapping” scenario—a situation that swaps the bodies of two women, Jane and Mary. If the mind seems distinct from the body, then it is conceivable that Jane would remain Jane, and maintain her idiosyncratic psychological characteristics even when she emerges from the body swap in Mary’s body. A stronger mind–body separation ought to elicit a stronger such belief (that Jane’s characteristics would persist in Mary’s body) in transgender people.

Across scenarios, then, we expect that the group differences should depend on the scenario (see Table 1). When the body is not preserved (in the afterlife and body swapping), transgender people would be more likely to state that a person’s psyche would persist. But this should not be the case when the situation preserves the body (in the body replication).

We further expect these intuitions to vary depending on the specific psychological characteristics of the protagonist. Past research has shown that people consider thoughts (e.g., abstract reasoning) as particularly ethereal, whereas traits like “seeing” seem strongly embodied (e.g., in the eyes)10,11,43. Accordingly, in each of our scenario, we contrast responses to thoughts (i.e., epistemic traits) with non-epistemic traits, such as sensations (e.g., seeing) actions (e.g., walking) and emotions (e.g., love).

If people separate minds and bodies, then they should consider thoughts (epistemic traits) particularly likely to persist without the body (in the afterlife, and the body-swapping scenario). And if transgender individuals show a stronger mind–body separation, then group differences ought to be strongest when the mind is likely to persist without the body—for thoughts (which seem more ethereal) and in the afterlife and body-swapping scenarios (situations that only allow the mind to persist).

Critically, all these psychological traits are entirely unrelated to gender identity. By gauging group differences in response to such traits, our research can explore whether the effects of transgender identity extend to matters that go far beyond questions of gender and sex. Our goal here is to determine whether transgender people show a stronger mind–body dissociation and whether its magnitude is linked to their own transgender identity—to their gender dysphoria, and the steps they took to transition.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 examined whether transgender people are more likely to view a person’s psyche as ethereal, distinct from their body. To this end, we presented transgender adults and Controls (n = 120 participants per group) with a list of 80 psychological traits, employed and validated in our past research39,40,44 (for details, see SM). Half of these traits were epistemic—they concerned thoughts (e.g., thinking about magic) and beliefs (e.g., belief in the super-natural), traits whose bodily source is not evident to laypeople44; the other half were non-epistemic traits, including emotions (e.g., love for one’s family) and actions (e.g., squatting down)—traits that people readily anchor in the body44,45.

Participants were asked to determine whether each of these traits would emerge in two opposing hypothetical scenarios. One scenario features the afterlife—a situation that obliterates the body; another scenario preserves the body, as here, people are invited to imagine an exact replica that preserves every aspect of a person’s flesh. The two scenarios were featured in two blocks (counterbalanced for order), and participants were asked to assume both scenarios exist (to combat floor effects). Their task was to indicate (yes/no) whether each such trait would emerge in the scenario in question. Of interest is whether the persistence of epistemic traits (relative to non-epistemic traits) differs in the two scenarios, and whether these differences further vary by group—for transgender participants vs. Controls.

We summarize the predictions in Table 2. If people segregate minds and bodies, then they would be expected to view epistemic traits as more ethereal, distinct from the body. Consequently, epistemic traits will seem as (a) more likely to persist when the body is obliterated, in the afterlife; but (b) less likely to persist when the body is preserved, in the body-replication scenario (relative to non-epistemic traits). A stronger mind–body separation, then, could, in principle, augment both of these effects, symmetrically.

For transgender people, however, the consequences of preserving the body may not be the mere mirror image of its obliteration. As noted, transgender people experience dissonance between their gender and their natal sex. To resolve this tension, many individuals opt to alter their bodies (rather than preserve their bodies and change their gender identity, which is a “conversion” solution that many transgender people find distressing46). And if transgender participants consider body-altering transformations as more likely to affirm a person’s identity (relative to body-preserving ones), then they may also consider the afterlife (a body-altering manipulation) as more likely to preserve the donor’s psychological traits in our experiment. Consequently, we would expect the stronger mind–body separation of transgender individuals to be more likely to manifest in the afterlife scenario. Compared to Controls, the transgender group should be more likely to assert that epistemic traits would persist in the afterlife.

Results

Mind–body intuitions

We evaluated the responses using a generalized linear mixed effects model, implemented with the glmer function of the lmer4 package 4 (response ~ task* trait * group + (trait|subject) + (1|item), family = “binomial”). In this model, task, trait and group are fixed effects; subject and item are random effects. Outliers (individuals whose means fell 2.5 SD beyond the group means; ten transgender and eight Control participants) were removed from all analyses. An analysis of the entire sample yielded similar conclusions (see SM and Fig. S1).

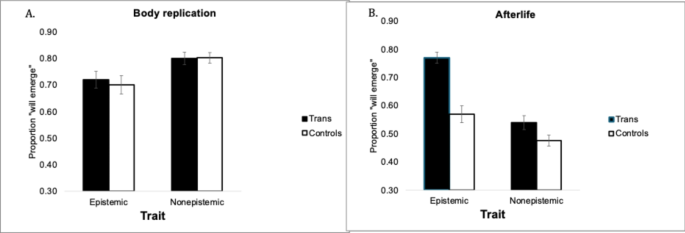

An inspection of the results (Fig. 1) suggested that when the donor’s body was preserved (in the body-replication scenario), emotions and actions (i.e., nonepistemic traits) seemed more likely to be present in the replica than thoughts and beliefs (i.e., epistemic traits), and this pattern did not differ by group. In contrast, when participants considered the afterlife (a situation that obliterates the body), epistemic traits now seemed more likely to persist (relative to non-epistemic traits), and this difference was stronger in transgender participants (relative to Controls). Accordingly, the logit model yielded a significant Task × Trait × Group interaction (β = 0.84, SE = 0.17, Z = 5.03, p < 0.001).

Perceptions of the mind–body divide in the transgender group relative to controls in the body-replication (A) and afterlife task (b). Error bars are SEs of the mean. Trans transgender.

To interrogate the three-way interaction, we next probed for the predicted Trait × Group interactions for each scenario separately (by removing the Task factor from the model). Results (Fig. 1A) showed that when the donor’s body was preserved (in the body-replication scenario), both groups considered emotions and actions (i.e., nonepistemic traits) as more likely to be present in the replica than thoughts and beliefs (i.e., epistemic traits; for the main effect of Trait: β = 1.31, SE = 0.37, Z = 3.52, p < 0.001). This is only to be expected, as past research has shown that epistemic traits do not seem strongly anchored in the body, whereas emotions and actions are44,45, so exactly copying the body ought to preserve non-epistemic traits. This effect, however, was not further modulated by Group (for the Group × Trait interaction: Z < 1) nor did the two groups differ (for the main effect of Group, β = 0.58, SE = 0.44, Z = 1.31, p > 0.19, n.s). Thus, when the scenario preserved the body, mind–body intuitions did not differ for transgender people and Controls.

The two groups, however, sharply diverged in their responses to the afterlife scenario (Fig. 1b)—a situation that obliterates the body, but potentially preserves the mind. Here, transgender people were more likely to assume that the donor’s psyche would endure than Controls were (for the main effect of Group: β = 1.19, SE = 0.26, Z = 4.54, p < 0.001). In addition, both groups considered epistemic traits as significantly more likely to be preserved than non-epistemic traits (for the main effect of Trait: β = − 1.01, SE = 0.35, Z = − 2.89, p < 0.01). Critically, this effect of Trait was stronger in the transgender group relative to the Control group, resulting in a significant Group × Trait interaction (β = − 0.94, SE = 0.22, Z = − 4.34, p < 0.001).

Tukey HSD tests showed that transgender persons considered epistemic traits as significantly more likely to endure in the afterlife than nonepistemic traits (β = 1.48, SE = 0.38, Z = 3.91, p < 0.001), whereas for Controls, this effect did not reach significance (β = 0.54, SE = 0.35, Z = 1.53, p > 0.42, n.s.). Additionally, transgender participants were more likely than Controls to state that psychological traits would be preserved in the afterlife, and this was the case for both epistemic (β = − 1.66, SE = 0.30, Z = − 5.58, p < 0.001) and non-epistemic traits (β = − 0.72, SE = 0.27, Z = − 2.68, p < 0.04). Thus, compared to Controls, transgender people were more likely to consider epistemic traits as resilient to the obliteration of the body.

Altogether, then, transgender individuals differed from Controls only for the afterlife scenario, and this difference was especially pronounced for epistemic traits. Group differences, then, emerged in a manipulation that obliterated the body and for traits that seemed strongly anchored in the ethereal mind. One concern, however, is that participants in the Control group were only identified by their binary gender (males or females). They were not explicitly asked whether their affirmed gender matched the gender assigned to them at birth, so it is conceivable that some participants were not cisgender.

To clarify the group difference, we obtained responses to the “cisgender” question from a subgroup of 60 Control participants. The results remained unchanged. The effect of Trait differed by Group only in the afterlife (β = − 0.89, SE = 0.25, Z = − 3.56, p < 0.001), but not in the replication scenario (β = 0.13, SE = 0.28, Z < 1). Consequently, the Group × Task × Trait interaction remained highly significant (β = 0.89, SE = 0.19, Z = 4.59, p < 0.0001). These results make it clear that transgender individuals differentiate minds and bodies more sharply than do their cisgender counterparts.

It is unlikely that these conclusions solely emerged because our participants were instructed to assume that the afterlife/replication scenarios exist. While such instructions could have potentially elevated the absolute proportion of “yes” responses, our conclusions rest on a relative pattern—the Trait × Task × Group interaction. Because the instructions applied equally to all conditions, they could not have elicited the pattern we observed.

Are mind–body intuitions linked to gender identity?

We next evaluated whether mind–body intuitions are linked to gender identity. To this end, we invited the transgender group to complete the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale47. This scale evaluates a person’s affirmation of their expressed gender (e.g., A life in my affirmed gender is more attractive for me than a life in my assigned sex) and their gender dysphoria—the distress that may accompany the incongruence between one’s experienced and assigned genders1 (e.g., I hate my birth-assigned sex). Item inter-reliability (across all 18 items) was high (Cronbach ⍺ = 0.908; SD = 67.96).

To examine whether these transgender participants affirmed their experienced gender, and exhibited gender dysphoria, we first compared the mean scores against the “neutral” midpoint of the five-point scale (3 = neither agree nor disagree). Results showed that the mean affirmation (M = 4.58, t(92) = 30.11, p < 0.001, d = 3.12) and gender dysphoria (M = 3.69, t(92) = 8.72, p < 0.001, d = 0.90) responses were both significantly higher than “neutral”.

Having established that this sample affirmed their experienced gender and exhibited some gender dysphoria, we next evaluated whether gender perceptions were linked to mind–body intuitions. To this end, we correlated participants’ gender-dysphoria and gender-affirmation scores with intuitions of mind–body separation (the difference in response to epistemic vs. nonepistemic traits, calculated separately for the replication and afterlife tasks). The full correlation matrix is presented in Table S2.

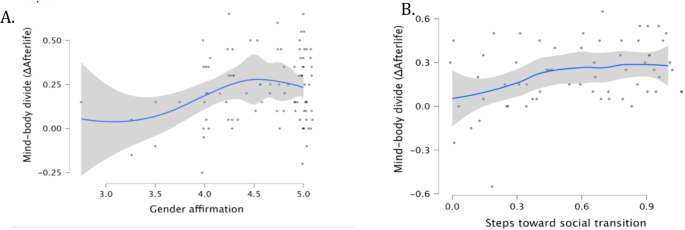

The correlation with the afterlife task was significant (r(91) = 0.21, p = 0.04). The stronger the affirmation of a person’s gender, the more likely they were to consider epistemic traits as more likely to persist in the afterlife (relative to non-epistemic traits; Fig. 2A). No such correlation was apparent for body replication (r(91) = − 0.11, p > 0.29, n.s.), and the two correlations—in the afterlife and replication conditions—differed reliably (Z = 2.7, p = 0.03); this is only to be expected, as the stronger mind–body separation in transgender individuals was evident only in the afterlife situation. There were also no correlations with dysphoria (in the afterlife: r(91) = 0.05, p > 0.63, n.s.; in body replication: r(91) = − 0.16, p > 0.12, n.s).

The correlation between mind–body separation and gender affirmation (A) and Steps taken towards social transition (B). Mind–body separation is captured by the perceived propensity of epistemic traits to persist in the afterlife relative to nonepistemic traits. The shaded area captures standard errors.

If mind–body separation is linked to the sex-gender dissonance, then it might also be linked to its resolution, via transitioning. Does the mind–body divide, then, correlate with the concrete actions taken by transgender people to transition? To find out, we invited the original group of transgender people to describe the steps they had taken to transition (social, medical, and cosmetic steps, using the transition scale48; see Table S3). In this sample, medical transition (surgical and hormone therapy) was infrequent (M = 0.29, SD = 0.31), but social transition (e.g., coming out, changing name, pronouns) was not (M = 0.57, SD = 0.32; see also Table S3). Item inter-reliability (across all 20 items) was high (Cronbach ⍺ = 0.92; SD = 10.52).

To determine whether the social transition was linked to mind–body intuitions, we correlated the proportion of social acts of transition (the proportion of reported acts of transition relative to the total number of questions) and mind–body separation (the difference in response to epistemic vs. nonepistemic traits, calculated separately for the replication and afterlife tasks; for the full correlation matrix, see Table S4). The correlation was once again significant for the afterlife scenario (r(60) = 0.36, p < 0.01, but not for the replication: r(60) = − 0.11, n.s.). In other words, the stronger the separation of minds and bodies (i.e., the more likely epistemic traits seemed to emerge in the afterlife relative to nonepistemic traits), the more likely acts of social transitioning were to be reported (see Fig. 2B). To ensure that this association was not an artifact of autistic traits39, we partialled out participants’ performance on the Autism Quotient (Cronbach ⍺ = 0.783; SD = 20.41)—the correlation between the steps taken toward social transition and the mind–body separation (in the afterlife) remained significant (r(59) = 0.351, p < 0.01). Thus, not only do transgender individuals exhibit a stronger mind–body separation but its magnitude is linked to their own personal transitioning.

Experiment 2

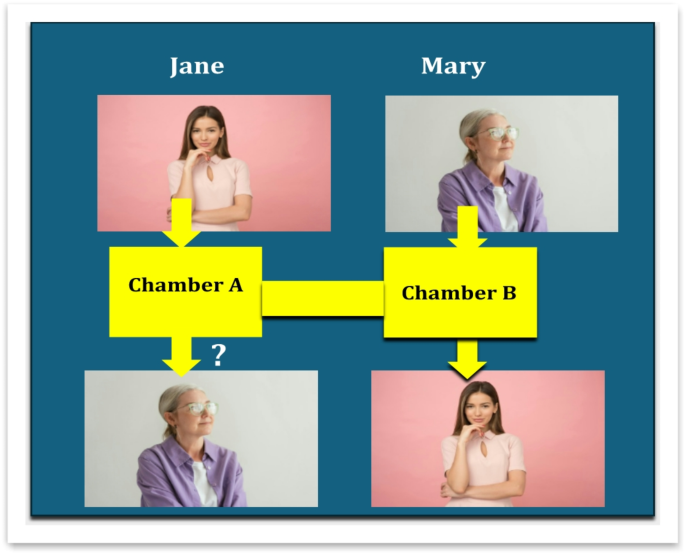

Having shown that transgender individuals are more inclined to state that thoughts can survive without one’s body, we next examined whether they believed that thoughts could persist in the wrong body—the body of another person. To this end, Experiment 2 (pre-registered; for details, see SM) presented participants with a body-swapping scenario. In this scenario, two women, Jane and Mary, swap their bodies. At the beginning of the procedure (see Fig. 3), the women enter a device with two chambers. Jane, the young protagonist, enters chamber A, whereas Mary, who is much older, enters chamber B. As the procedure ends and the door of chamber A opens, out comes a woman who looks just like Mary (see Fig. 3).

Illustration of the body-swapping procedure. Note: all images are taken from https://www.pexels.com/; they are copyright- and royalty free.

Participants were invited to consider that woman and answer two questions about her. The first asked how likely the woman was to exhibit Jane’s psychological traits— epistemic (e.g., Knows her spouse’s name is Bob) and nonepistemic (e.g., Jealous when other women look at Bob, her spouse). Importantly, all traits were idiosyncratic; they only applied to Jane, not to Mary, and participants were explicitly informed of this fact. The second question asked who the woman was—Jane or Mary?

If people segregate minds and bodies, and if they further define personal identity by one’s mind, then they ought to conclude that Jane could still remain Jane, even in Mary’s body, and maintain her idiosyncratic psychological characteristics. Since epistemic traits seem particularly ethereal44,45, they would seem more likely to persist without Jane’s body. A stronger mind–body separation in transgender people should thus manifest primarily in response to epistemic traits (akin to the pattern observed in the afterlife scenario), and it should further correlate with the attitudes of transgender participants toward their own gender.

Mind–body separation, however, may not be sufficient for these intuitions to emerge.Footnote 1 To state that Jane could inhabit Mary’s body, people must further tolerate the persistence of her identity in the wrong body. And whether people—especially, transgender people—would do so is uncertain, as the incongruence between gender identity and sexual, bodily anatomy is a matter of acute concern for them46. We thus expect group differences in mind–body intuitions to emerge only if participants identified the protagonist as Jane. We administered the body-swap questions to 200 participants (N = 100 per group; one transgender participant was removed as an outlier. For pre-registration information, see SM).

Results

Is it Jane?

We first examined participants’ intuitions about who the protagonist (the person leaving room A) was. Nearly half of the transgender (M = 0.49) and cisgender (M = 0.48) participants identified the woman exiting chamber A as Jane. This proportion did not vary by group (Z < 1) nor did it differ from chance (Z < 1).

This at-chance response is open to different interpretations. One is that participants were confused about who the protagonist was; the other is that they were quite clear on this matter, but some participants were confident it was Jane, and others were confident it was Mary. To adjudicate between these possibilities, we next examined whether participants who identified the protagonist (the person leaving room A) as Jane further ascribed to her Jane’s idiosyncratic psychological traits (this analysis was not registered). We reasoned that if participants identify the protagonist as Jane, then they ought to ascribe her Jane’s unique psychological traits. Accordingly, when participants identified the protagonist as Jane, their mean response to her psychological traits (the proportion “yes” responses affirming that Jane’s psychological traits would persist) should exceed chance. This, however, should not be the case when they identify the protagonist as Mary.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we extracted the proportion of responses affirming the persistence of Jane’s psychological traits separately for participants who identified the protagonist as Jane vs. Mary. We next compared those means against chance using a logistic regression model, with participants and items as mixed effects (response ~ (1|subject) + (1|item).

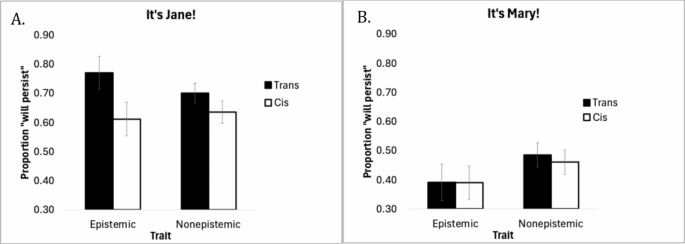

Results suggested that participants were quite confident about their responses. When participants identified the protagonist as “Jane,” (Fig. 4A) the means for transgender participants were significantly above chance for both epistemic (M = 0.77, β = 10.02, SE = 1.42, Z = 7.04, p < 0.0001) and nonepistemic traits (M = 0.70, β = 1.29, SE = 0.23, Z = 5.61, p < 0.0001); for cisgender participants, the mean was above chance for non-epistemic traits (M = 0.67, β = 0.76, SE = 0.22, Z = 3.40, p < 0.0001) and marginally so for epistemic traits (M = 0.61, β = 1.24, SE = 0.69, Z = 1.80, p = 0.07). Thus, when participants identified the protagonist as Jane, they assumed that she would exhibit Jane’s idiosyncratic psychological traits. As expected, this was not the case when the protagonist was identified as Mary. Here, all means were numerically below chance (Fig. 4B; for additional tests, see Table S6). It thus appears that participants were quite clear about who the protagonist was. With this in mind, we can next move to our main question: did the groups differ with respect to their intuitions about minds and bodies?

Responses to the body-swapping procedure, plotted by the perception of the protagonist as Jane (A) or Mary (B). Trans transgender participants, cis cisgender participants. Error bars are standard errors of the means.

Intuitions about minds and bodies

An inspection of the means (Fig. 4) suggested that mind–body intuitions varied by group. When the woman exiting room A was identified as Jane, transgender people were more likely to state she would maintain Jane’s epistemic traits than cisgender participants. But when the woman was seen as Mary, the groups did not differ, and they both considered Jane’s epistemic traits less likely to persist.

To evaluate these observations, we first submitted the responses to a mixed effect model (response ~ Trait * Group* Identity (Jane/Mary) + (Trait|subject) + (1|item), family = “binomial”). In this model, Trait, Group, and Identity are fixed effects; subject and item are random effects. The three-way interaction was significant (β = 3.28, SE = 1.53, Z = 2.14, p = 0.03); the main effect of Protagonist was significant as well (β = 2.92, SE = 0.56, Z = − 5.19, p < 0.0001; for the full results, see SM). To interrogate this interaction, we next analyzed the responses separately, depending on whether the protagonist was identified as Jane or Mary (response ~ Trait * Group + (Trait|subject) + (1|item)).

It’s Jane

When the protagonist was identified as Jane, we found significant effects of Trait (β = − 2.35, SE = 0.66, Z = − 3.54, p < 0.0001) and Group (β = 1.98, SE = 0.80, Z = 2.46, p = 0.02), as epistemic traits were considered more likely persist (than non-epistemic traits) and transgender people considered Jane’s traits as more likely to persist than cisgender people did. Critically, the Group × Trait interaction was significant (β = − 3.22, SE = 1.19, Z = − 2.70, p < 0.01).

Tukey HSD tests showed that transgender participants considered Jane’s epistemic traits more likely to persist than her non-epistemic traits (β = 3.96, SE = 1.00, Z = 3.94, p < 0.001). This, however, was not the case for cisgender participants (Z < 1). Additionally, the mean response of transgender participants was higher than cisgender participants for epistemic traits (β = − 3.59, SE = 1.38, Z = − 2.61, p < 0.05), but not for non-epistemic traits (β = − 0.38, SE = 0.33, Z = − 1.15, p > 0.67). Thus, compared to cisgender participants, transgender participants were more likely to state that, despite her new body, Jane would still maintain her epistemic traits.

It’s Mary

When the protagonist’s identity seemed to change (i.e., when identified as Mary), the effect of Group and the interaction did not approach significance (both Z < 1). However, the main effect of Trait was significant (β = 1.26, SE = 0.51, Z = 2.46, p = 0.02), as Jane’s epistemic traits now seemed less likely to persist. This intuition could have either arisen because epistemic traits seem more central to one’s identity (hence, less likely to persist in another person) or because non-epistemic traits seem embodied, hence, more likely to transfer to Mary’s body by “contagion” from Jane’s body. Either way, when the protagonist’s identity changed, the responses of the two groups did not differ.

Thus, group differences only emerged when Jane seemed to maintain her identity and only for her epistemic states. This selectivity makes it clear that transgender participants are not merely biased to respond “yes.” This selective pattern is in line with the hypothesis that transgender people separate bodies and minds more than cisgender people do.

Are intuitions about minds and bodies linked to gender identity?

We next examined whether mind–body intuitions correlated with the gender identity of transgender participants, as measured by the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale47 and the steps they took to transition (described in Experiment 1).

Gender identity

We first examined the gender identity of this sample. One-sample t-tests, comparing the mean response to the scale’s “neutral” midpoint (3 = neither agree nor disagree) indicated that participants affirmed their chosen gender (M = 4.45; t(96) = 26.12, p < 0.001; Cohen d = 2.65) and showed significant dysphoria toward the gender assigned to them at birth (M = 3.71; t(96) = 8.48 p < 0.001; Cohen d = 0.861). Two-sample t-tests further indicated that gender affirmation, dysphoria and transitioning did not differ for participants who identified the protagonist as Jane or Mary (all p’s > 0.15).

We next examined whether gender perceptions correlated with mind–body intuitions. Our predictions for body-swapping, however, differ from the afterlife scenario (described in Experiment 1). This is because the afterlife obliterates the person’s body, whereas in the body swap, a person’s identity transfers to the wrong body—a situation known to engender dysphoria in transgender individuals and motivate transitioning. Accordingly, to accept that Jane’s psyche could persist in the wrong body, people must tolerate a mind–body dissonance, and if they do so for Jane, they might also do so personally. We thus predicted that participants who tolerated the persistence of Jane’s psyche in the wrong body would show more tolerance of their birth-assigned gender and lesser dysphoria toward it. Results (Fig. 5) were in line with this prediction (for the full correlation matrix, see SM, Tables S7–S9). We next describe them according to how the protagonist was identified—as Jane or Mary.

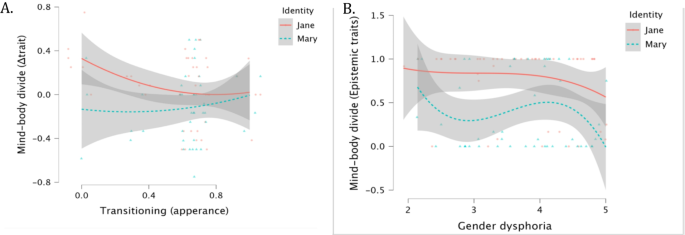

The correlation between mind–body intuitions and gender identity. In Panel (A), mind–body intuitions are captured by the differential response to Jane’s epistemic-minus non-epistemic traits; gender identity is captured by the steps taken to alter one’s appearance. In Panel (B), mind–body intuitions are captured by responses to Jane’s epistemic traits; gender identity is captured by dysphoria towards one’s birth-assigned gender. The shaded bands capture standard errors.

It’s Jane

For participants who identified the protagonist as Jane, mind–body separation (the differential response to Epistemic–Nonepistemic traits) correlated negatively with the steps they took to transition by altering their appearance (r(41) = − 0.324, p = 0.03). Mind–body intuitions, however, also correlated negatively with participants’ scores on the Autism Spectrum Quotient scale (AQ; r(46) = − 0.315, p = 0.03). To ensure that the association between mind–body intuitions and transitioning was not an artifact of autistic traits39, we next reevaluated the correlation after partialling out the AQ scores (this exploratory analysis was not pre-registered).

Once AQ was controlled for, the original correlation (between mind–body intuitions (∆trait) and steps taken to alter one appearance) became even stronger (r(40) = − 0.437, p = 0.4). In addition, mind–body intuitions correlated negatively with gender dysphoria. Specifically, the more likely participants were to state that Jane would maintain her epistemic (i.e., disembodied) traits, the weaker their gender dysphoria (r(45) = − 0.292, p < 0.05). Dysphoria scores did not significantly correlate with response to nonepistemic (i.e., embodied) traits (r(45) = − 0.189, p > 0.21). Summarizing, participants who tolerated the persistence of Jane’s identity in the wrong body were more likely to tolerate incongruence between their affirmed- and birth-assigned genders—they showed weaker dysphoria toward the gender assigned to them at birth and reported that they had taken fewer steps to transition.

It’s Mary

Participants who identified the protagonist as Mary (in line with her body) showed the opposite pattern. The stronger the mind–body separation (the more likely they were to state that the protagonist (Mary) would maintain Jane’s epistemic- relative to non-epistemic traits), the more likely they were to report transition overall (r(46) = 0.336, p = 0.03) and to take social (r(46) = 0.315, p = 0.04) and medical steps (r(46) = 0.393, p = 0.01) to transition. The mind–body separation did not further correlate with AQ in this group (r(48) = 0.242, p = 0.093). Thus, participants who did not tolerate an incongruence between Jane’s identity and her body were also less likely to do so personally: they were more likely to mitigate the incongruence between their affirmed- and birth-assigned genders—the stronger their perception of the mind–body divide in the protagonist, the more likely they were to transition. Taken together, results from Experiment 2 show that transgender participants exhibit greater separation of minds and bodies. Their perception of the mind–body separation in a protagonist also correlates with their attitudes toward their birth-assigned gender.

General discussion

Transgender people consider their gender (a psychological, mental construct) as distinct from their natal gender, assigned by their sex (their body), whereas cisgender people do not. Does this psychological difference between transgender and cisgender people only concern a contrast between gender and sex, specifically, or a broader difference in the perception of minds and bodies, generally?

To shed light on this matter, here, we explored the sex-gender tension in transgender people. Our results show for the first time that, compared to cisgender participants, transgender individuals perceive the mind as more distinct from the body, and as more central to a person’s identity. Moreover, intuitions regarding the mind–body separation correlate with participants’ perceptions of their own gender identity and the steps they have taken to transition.

Considering mind–body intuitions, transgender individuals were more likely than cisgender individuals to state that psychological traits that capture thoughts and beliefs (traits that seem particularly disembodied) would persist without their body—when their body is obliterated (in the afterlife) or altered (in body-swapping). Moreover, transgender people were more likely to state that a person (Jane) would maintain her idiosyncratic psychological characteristics (mostly her thoughts and beliefs) in the wrong body (that of of Mary’s). Together, these results suggest that transgender participants show a stronger separation of mind and body and that they are also more likely to align the self with the mind (compared to cisgender participants). Interestingly, transgender people did not show the converse—they were no more likely than cisgender people to believe that embodied psychological traits (sensations, actions and emotions) would persist once the body is preserved (in the body replication scenario). Thus, their more robust mind–body separation only emerged in scenarios that altered (obliterated or swapped) the protagonist’s body, but not when it was preserved (i.e., in body replication).

This asymmetry is in line with how transgender participants resolve the tension between their own affirmed gender and their natal sexual anatomy—they typically choose to alter their body, rather than preserve it (and reject their affirmed gender, a proposition that transgender people find deeply distressing46). It is conceivable that this correspondence arises from a common cause. If transgender people consider body alteration as a more suitable strategy for affirming personal identity, generally (rather than gender identity alone), and if identity resides in one’s mind, then they ought to conclude that body alteration—either of their own body or the experimental protagonist—can better preserve personal identity, especially, one’s ethereal mental characteristics. For this reason, group differences in mind–body separation would manifest asymmetrically, only when the body is altered, just as the results show. Thus, transgender identity may be linked to mind–body attitudes.

Indeed, intuitions regarding the mind–body divide correlated with participants’ gender identity. Furthermore, the direction of these links varied lawfully across scenarios. When the protagonist’s body was obliterated (i.e., in the afterlife; Experiment 1) or matched her identity (when the protagonist had Mary’s physical body and was identified as such, in Experiment 2), participants who showed a greater mind–body separation were more likely to affirm their gender identity (in Experiments 1) and to report more efforts toward transition (in Experiments 1–2). In contrast, participants who tolerated the possibility that a protagonist’s mind could land in the wrong body (when she was identified as Jane, in Experiment 2) were also more likely to tolerate a mismatch between their affirmed gender and the gender assigned to them at birth (based on sexual anatomy). This group showed weaker gender dysphoria and were less likely to report transition. Altogether, then, mind–body attitudes depended on (a) the separation of minds and bodies, and (b) the tolerance of their incongruence. Critically, these factors engendered parallel attitudes toward gender identity and the experimental protagonist. The parallelism suggests that the attitudes of transgender individuals towards their gender are linked to their beliefs about bodies and minds, generally.

Why do transgender individuals show stronger mind–body separation? As noted in the introduction, differences in mind–body separation could be either a cause of transgender identity or a consequence. The cause explanation states that the incongruence between gender and anatomical sex arises, in part, because transgender people are more prone to separate minds and bodies. A major challenge to this proposal is to explain why such differences might exist. Past research has linked the separation of minds and bodies to strengths in mind-reading39,40, but in transgender people, mind-reading tends to be weaker54,55. Moreover, the prevalence of transgender identity can diverge from mind–body intuitions. For example, autistic people show a weaker mind–body separation39 but they are more likely to identify as transgender56. Thus, it is unclear why transgender people might be prone to mind–body separation. Another problem is that this cannot singlehandedly explain why many transgender people contrast their affirmed gender and their natal sexual anatomy rather than merely differentiate between them.

Alternatively, and perhaps more plausibly, the greater mind–body separation could be a consequence of transgender identity. As a transgender person grows consciously aware of the dissociation between their own sex and gender, they may become more likely to contrast bodies and minds generally. And of course, the greater separation of minds and bodies could be both a cause of transgender identity and its consequence.

The precise links between intuitions of the mind–body separation and transgender identity warrant clarification in future research—our present results cannot speak to this question. Our research did not seek to explain why transgender people show a stronger mind–body separation. We have simply demonstrated its existence.

These conclusions shed light on transgender cognition. Our results show for the first time that transgender and cisgender persons show systematic cognitive differences in reasoning about minds and bodies that go far beyond currently known differences in gender cognition57. Moreover, while some assume that the concerns of transgender people with bodily transitioning suggest a stronger focus on the physical body, our results, in fact, show just the opposite. In the eyes of transgender people, the self is aligned more strongly with the ethereal mind, rather than with the body.

Finally, these conclusions offer new insights into the human psyche. A large literature has shown that the perception of the mind–body divide shapes reasoning8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Our present results suggest that the psychological consequences of the mind–body divide could go far beyond what has been previously recognized. Perceptions of the mind–body divide are linked to gender identity—a core aspect of the self. Not only could the mind–body divide guide how we think, but quite possibly, how we consciously experience the self, me.

Materials and methods

Participants

Experiments 1–2 each included two groups of participants: transgender participants and controls. Both groups were young adults (age 18–40), native English speakers, who self-identified as neurotypical (with no diagnosis of autism) with no known language or reading disorders. All participants were Prolific workers, compensated at a rate of $1/five minutes (for demographics, see Tables S1 and S5).

Transgender people (n = 120; in Experiment 2: n = 100) further identified their current gender as different from the one assigned to them at birth. Twenty-six of the transgender participants in Experiment 2 also took part in Experiment 1, administered 4 months earlier. Of the transgender participants in Experiment 1, 67 identified as women, 44 as men, and 9 did not indicate their gender; In Experiment 2, 56 identified as women, 37 as men, and 6 did not identify their gender.

In Experiment 1, Controls (n = 120) identified as males and females (but not as non-binary); half self-identified as cisgender (i.e., they explicitly stated that their current gender matches the one assigned to them at birth); the remaining Controls identified as males and females, but were not explicitly asked about their cisgender status. In Experiment 2, Controls were 100 cisgender participants.

Sample size for Experiment 1 was informed by past research, where a sample size of M = 30 was sufficient to reveal significant group differences in mind–body separation39. To reveal individual differences within groups, we arbitrarily quadrupled the sample size (N = 120 per group). A power analysis of Experiment 1’s results suggested that the selected sample size had virtual certainty to reveal the interaction of interest (CI 96.38–100%, ⍺ = 0.05); so in Experiment 2, we set the sample size to N = 100 per group.

Informed consent. All materials and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Northeastern University; all methods were performed in accordance with those guidelines and regulations. An informed consent form was obtained from all participants or their parents/legal guardians.

All images appearing in this manuscript are publicly available on the Internet; they do not capture any study participant.

Mind–body intuitions

To gauge mind–body intuitions, in Experiment 1, we used a list of 80 psychological properties that are likely characteristics of all humans58, so here we refer to them as traits. Half of those traits captured knowledge and beliefs (e.g., Having classification of animals, hereafter epistemic traits); the other half consisted of actions and emotions (e.g., sitting, walking, hereafter non-epistemic traits). All traits were vetted extensively in past research39,40,43,44.

Each participant was asked to determine the propensity of each trait to emerge in two hypothetical situations. The body-replication scenario invited participants to suppose it were possible to grow a replica of the body of an adult human donor. The replica preserves every aspect of the human body and brain. With this in mind, participants were asked to determine whether or not a given trait would likely emerge in the replica. In the afterlife scenario, participants were invited to judge whether each trait will persist in the afterlife. Participants were told that whether or not there is an afterlife is unknown. But for the purpose of this experiment, they were asked to assume that after people die, they do continue to exist in some capacity. The task was to reason about which human traits would be likely be maintained in the afterlife (for the full instructions, see SM, Appendix 2). Each such task featured half of the traits, and the task order was counterbalanced across participants. Trait order was randomized. For the full list of traits, see SM, Appendix 1.

Experiment 2 features a body-swap scenario. Participants were asked to “suppose it was possible for two people to swap bodies. At the start of the procedure, two women, Jane and Mary, enter a special device; Jane, a young woman, enters chamber A, whereas Mary, who is older, enters chamber B.”… “Then, the machine starts working. When it’s done, the technician opens the door of Chamber A (where Jane just entered) and out comes a woman who looks just like Mary (whereas the woman exiting Chamber B looks just like Jane). “Participants were further shown photos of Jane and Mary, chosen to accentuate their physical differences. In so doing, we sought to make it clear that physically, the two women were unmistakably different.

Participants were presented with 24 traits Jane had before the body swapping (randomized); they were told that these characteristics only applied to Jane, and not to Mary. Half of these traits captured epistemic states (e.g., Knows her spouse’s name is Bob) the other half captured emotions, actions and sensations (e.g., Jealous when other women look at Bob, her spouse). Participants were first asked to state whether the woman existing the body-swap would still maintain these traits. Finally, they were asked to state whether this woman is Jane or Mary (for the instructions and traits, see Appendix 5; for pre-registration information and additional analyses, see SM and Fig. S2).

Autism quotients

Since past research has linked transgender identity to autism54,55, which, in turn, attenuates the separations of minds and bodies39, we screened for autism using the Autism Spectrum Quotient (from59); this test asks participants to respond to fifty short sentences, related to their social skills, attention switching, attention to detail, communication, and imagination.

Gender affirmation and dysphoria

The affirmation and dysphoria were evaluated using the Utrecht Gender Dysphoria Scale47 (Appendix 3). The survey consists of 18 questions that gauge a person’s dysphoria and the affirmation of their chosen gender. Responses are given on a 1–5 scale (1 = disagree completely; 2 = disagree; 3 = neither agree nor disagree; 4 = agree; 5 = agree completely).

Transitioning questionnaire

To learn about the steps taken by transgender participants to transition, we presented them with 20 questions. 16 items (from48, see SM, Appendix 4), inquiring about the steps taken to transition in appearance, socially, and medically; four additional questions inquired about the steps participants wished to take and whether they had the opportunity and resources. For each question, participants could respond as either yes, no, or “I don’t wish to respond”.

The gender affirmation and transitioning scale were administered separately from the main experiment, so these results were not available for all participants. In Experiment 1, data on the Dysphoria scale were collected from 97 participants (of these, four individuals were excluded, as their scores in the Utrecht test fell 2SD below the group means); the gender transitioning scale was collected from 63 participants (one was removed because they declined to respond to all questions). In Experiment 2, the Dysphoria scale was collected from 97 participants; the transitioning scale was recorded from 86 participants.

Responses