The impact of solar elevation angle on the net radiative effect of tropical cyclone clouds

Introduction

Clouds are one of the main sources controlling the Earth’s energy balance (EEB) and can affect the climate system1,2,3. Tropical cyclone (TC) clouds contribute to the EEB through both their longwave (LW) and shortwave (SW) radiation components at the top of the atmosphere. Until recently TC clouds and non-TC clouds had not been segmented, so the specific effects of TC clouds on the upwelling radiation could not be calculated. Although tropical mesoscale convective systems had been labeled using geostationary satellite infrared images4, this algorithm can only identify a part of the total area of TC clouds since the threshold for detecting systems is a brightness temperature of 235 K in satellite images. TC segmentation results using deep learning are optimized for detecting TCs rather than identifying TC clouds, so the segmentation results are not detailed enough to analyze radiative effects of TC clouds at the pixel level5,6,7. TC clouds were first segmented using a semi-automated algorithm8, and more recently, researchers have adopted a convolutional neural network for this task9. Using these segmentations8, the net radiative effect of TC clouds on EEB was quantified8,9,10. Compared with the non-TC cloud climatology, 74% of TCs increase the upwelling radiation through the effect of their clouds at the top of the atmosphere (i.e., are net cooling) and the other 26% of TCs decrease the upwelling radiation (i.e., are net warming)10. The overall net cooling effects from TC clouds amount to 8% of the total surplus warming energy driving the climate system10,11, implying that future changes in TC activity may have a sufficiently large effect to influence the EEB. However, the factors determining whether a specific TC results in net cooling or net warming have not been identified. Understanding these factors is critical, as the balance between net cooling and net warming in TCs directly affects the overall impact on the EEB1,2.

In this study, the effects of solar elevation angle, one of the factors determining cloud radiative forcing12,13, as well as various TC characteristics on the net upwelling radiation from TC clouds are analyzed. Furthermore, to diagnose how changes in TC activity affect net radiative effects of TC clouds, the past twenty-year trends for TC features were investigated. Finally, the potential implications for changes in TC cloud net radiation in the future were discussed. The “TC net radiation” referred throughout the text is defined as the net upwelling radiation caused by TC clouds within the boundaries of the TC segmentation cloud mask8,9,10, which can include both cloudy and clear sky regions. However, it does not include clear sky regions outside the TC cloud mask, even though these areas might be influenced by TC circulation. Expanding the TC segmentation masks to include these areas is an area of ongoing study.

Results

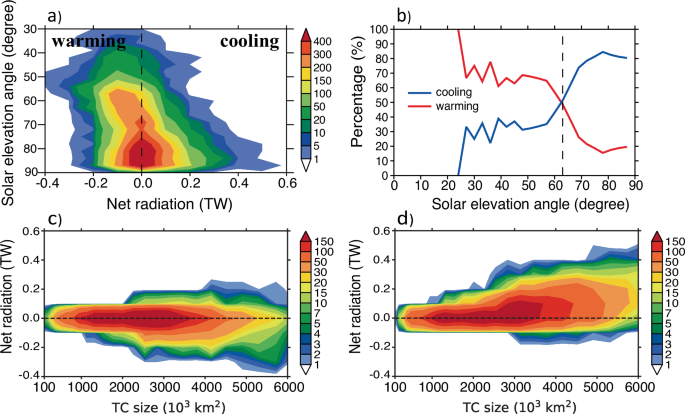

The outgoing LW radiation per TC cloud pixel remains nearly constant throughout the day and is similar in both net cooling and net warming TC cases (Supplementary Fig. 1). In contrast, the outgoing SW radiation per TC cloud pixel varies strongly through the day and differs significantly between net cooling and net warming TCs. This implies that the amount of SW radiation reflected by TC clouds during the daytime, which can be influenced by the intensity of incident SW radiation and TC size (see “Methods”), primarily determines the sign of the TC’s net radiation contribution. The solar elevation angle is a dominant factor that determines whether the effect of TC net radiation on the EEB is net cooling or net warming (Fig. 1a). The solar elevation angle refers to the maximum solar elevation angle at local noon (see “Methods”) rather than the instantaneous solar angle at each hour. The TC net radiation corresponding to each solar elevation angle represents the total daily solar radiation. Positive net radiation indicates that TC clouds contribute to net cooling at the top of the atmosphere (see “Methods”). When the solar elevation angle is low, warming TC days are more frequent than cooling TC days. The number of cooling TC days becomes predominant over the number of warming TC days as the solar elevation angle increases (Fig. 1a). The probability of cooling TC days exceeds warming TC days when the solar elevation angle θs ≥ 63° (Fig. 1b). In contrast, the relationship between the TC net radiation and latitude of the TC center is unclear (Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, through the rest of this paper, we will separate out analysis into “low solar elevation angle TC cases” where θs < 63° and “high solar elevation angle TC cases” where θs ≥ 63°. Generally, TCs with low solar elevation angles produce warming TCs (Fig. 1c; Supplementary Table 1), because they contribute less SW radiation to the daily TC net radiation than LW radiation. These effects are due to a relatively shorter day and more grazing incidence angle. Meanwhile, TCs with high solar elevation angles tend to produce cooling TCs because they contribute more SW radiation to the daily TC net radiation than LW radiation (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Table 1).

a Frequency in TC days for TC net radiation and solar elevation angle. b The percentage of net cooling and net warming TC days versus solar elevation angle. Frequency in TC days for TC size and TC net radiation in terms of TC cases with (c) low and (d) high solar elevation angles.

The TC net radiation is also affected by TC size. As the TC size increases, the magnitude of the TC net radiation increases regardless of whether the solar elevation angle is low or high (Fig. 1c, d). Unlike TC size, the relationship between TC intensity and TC net radiation is unclear (Supplementary Fig. 3). There are exceptions to the above generalization that cooling (warming) TC days occur under low (high) solar elevation angle conditions (Fig. 1). The exceptions are associated with the TC size, which can change across the diurnal cycle. The net cooling TCs with low solar elevation angles typically have more clouds during the daytime, especially near local noon when the SW radiation is the strongest, so the reflection of incoming SW radiation increases more than normal (Supplementary Fig. 4). The net warming TCs with high solar elevation angles have more clouds during the nighttime, so the attenuation of LW radiation by the TC clouds increases more than normal (Supplementary Fig. 4). Overall, the solar elevation angle is the key factor determining whether the net radiative effect of TC clouds is warming or cooling, with the TC size being the second most influential factor.

To investigate the TC net radiation in more detail, we analyzed its annual variations by correcting for differences in monthly TC activities based on whether TCs occur in the Northern or Southern Hemispheres. The TC season is divided into two parts: early season (1–140 days after the vernal equinox) and late season (141–365 days after the vernal equinox). The solar elevation angles corresponding to early-season TCs are generally greater than those of late-season TCs (Supplementary Fig. 5a and b). Thus, net cooling (warming) effects from TC clouds are predominant in the early (late) season (Supplementary Table 2). For the 2016–2020 period compared to 2001–2005, total TC days have decreased in the early season for TCs with high solar elevation angles (Supplementary Fig. 5c), which implies that the impact of TC clouds on net cooling in the early season may be reduced compared to the past (i.e., increased warming effect for the EEB) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Meanwhile, total TC days have increased in the late season for TCs across almost all solar elevation angles (Supplementary Fig. 5), which makes it more difficult to observe any impact on the EEB in the late season. To investigate the seasonal effect of TC activity shifts on the annual EEB, TC days, TC size, and TC net radiation were analyzed in detail by separating them by early and late seasons into cooling TC days and warming TC days (Fig. 2).

a, d, g Frequency in TC days, (b, e, h) TC size, and (c, f, i) TC net radiation for cooling TCs (blue line), warming TCs (red line), and all TCs (black line) in (a–c) early season, (d–f) late season, and (g–i) all season during 2001–2020.

Over the past twenty years, annual TC days increase slightly (Fig. 2g; Supplementary Table 3), which is consistent with a global trend of a small increase in TC frequency during 1990–202114. Previously reported trends for TC frequencies in each ocean basin during 1990–202114 and 1980–202115 are similar to those for TC days in this study (Supplementary Table 4). Moreover, TC day frequencies presented in this study are consistent with previous results during the common analysis period of 2001–200416 and 2001–200817. However, when separated by early and late season activity, TC days decrease significantly (−21 ± 18 days per decade) during the early season and increase significantly (41 ± 31 days per decade) during the late season (Fig. 2a, d; Supplementary Table 3). The shifts of seasonal TC activity seem to be a global phenomenon since TCs for each Ocean basin contribute to the shift except those for the Eastern North Pacific and North Atlantic Ocean basins for the early season and a South Indian Ocean basin for the late season (Supplementary Table 4). In the early (late) season, the changes in TC days result in a significant decrease (increase) in cooling TC days, explaining the additional warming (cooling) effects on the EEB (Fig. 2c and f; Supplementary Table 3). Overall, there is no significant change in global TC net radiation (−0.3 ± 2.2 TW per decade) during the twenty-year period (Fig. 2i; Supplementary Table 3), which may be related to decreasing TC cloud size in both the early (−77 ± 152 × 103 km2 per decade) and late (−138 ± 60 × 103 km2 per decade) seasons (Fig. 2b and e; Supplementary Fig. 6). Since TC clouds have less pronounced effects on net cooling or net warming as the TC size decreases (Fig. 1c and d), the significant changes in TC days for the early and late seasons mainly affect TC cases with low net radiation intensities (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Table 5). Thus, the effect of TC clouds on the EEB has remained stable over the last two decades.

Discussion

This study helps to explain our earlier results that showed a net cooling effect due to TC clouds but with significant storm-to-storm variation10. Further investigation reveals that TCs with high solar elevation angles generally have net cooling effects on the climate system, whereas TCs with low solar elevation angles have net warming effects. As the TC cloud area increases, the net cooling or net warming effect of a particular storm tends to be amplified, but size itself is not a strong indicator of total radiation. Furthermore, the diurnal variation in TC cloud area also plays an important role in modifying the TC net radiation, since clouds contribute to more SW reflection during the day and LW attenuation during the night, respectively.

For the period from 2001 to 2020, the number of cooling TC days decreased significantly in the early season (i.e., net warming effect) but increased significantly in the late season (i.e., net cooling effect). At the same time, TC size decreased in both parts of the season. Because of the combined influences of these two factors (i.e., TC days and TC size), the effect of a seasonal shift in TC activity on TC net radiation occurred mostly in TC cases with low net radiation intensity. There appears to be a delicate balance between shifts in the TC frequency seasonal cycle and TC size changes, leading to a stable contribution of the global TC net radiation to the Earth’s energy balance. Thus, no noticeable trend in the TC cloud net radiation was found over the last twenty years.

Considering that the magnitude of the TC net radiation amounts to approximately 8% of the Earth’s surplus energy10 and contributes to maintaining the stability of the climate system1,2,3, further research is required into the physical mechanisms that control this balance based on longer time periods in order to understand the potential feedback between TCs and the Earth’s energy balance. Additionally, using the cloud segmentation algorithm8,9 and estimated upwelling radiations, TC cloud net radiation can be calculated in different climate models and its impact on the Earth’s energy balance can be evaluated, which can help to understand and reduce uncertainty in climate prediction model results.

Methods

Data

To quantify the net upwelling radiation of TC clouds for the period from 2001 to 2020, two datasets were used. The first is the TC cloud mask labels for all global TCs during 2001–2020, which are calculated using the National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) Climate Prediction Center (CPC) Global Merged IR Brightness Temperature Dataset (GPM_MERGIR) with 4-km spatial resolution18 based on a semi-automated TC clouds segmentation algorithm8 developed by our research group. The detailed segmentation algorithm and step-by-step example figures can be found in Nguyen et al.8. The second dataset is radiative flux observations at the top of the atmosphere from the Clouds and Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES) Synoptic 1-degree dataset edition 419,20. The net upwelling radiation of TC clouds is calculated by subtracting the upwelling radiation based on the non-TC-cloud climatology from the total cloud upwelling radiation6. Thus, positive net radiation values indicate cooling effects of TC clouds on the EEB. Cooling and warming TC days refer to the case where the signs of the TC net radiation aggregated over 24 h are positive and negative, respectively.

The process of calculating the net upwelling radiation of TC clouds is summarized as follows. The CERES dataset provides upwelling radiations under all-sky or clear-sky conditions at 1 h intervals as:

where the i and j indicate pixel indices for latitude and longitude, respectively. The upwelling radiation of clouds at a fixed moment is defined as:

For each latitude, longitude, hour, and day, 20 values of ({R}_{{up_cloud}}) are available corresponding to the 20-year experimental period (i.e., 2001–2020). The upwelling radiation based on the non-TC-cloud climatology from 2001 to 2020 is calculated as:

where the maximum number of data points is 20. However, pixels identified as TC clouds are excluded to obtain the ({R}_{{up_nonTCcloud_clim}}), so the number of data points can be less than 20. The number of data points in Eq. (4) is more than 10 for the majority of cases even in the high TC frequency regions such as the Western Pacific, the Eastern Pacific, and Northern Australia10. Thus, for a given latitude and longitude (i.e., TC cloud pixel) at a fixed moment, the net upwelling radiation of TC clouds (i.e., ({R}_{{net_up_TCcloud}})) is calculated as:

where ({R}_{{up_TCcloud}}) is the upwelling radiation (Eq. 3) and ({R}_{{up_nonTCcloud_clim}}) is the non-TC-cloud climatology (Eq. 4). Finally, the total sum of ({R}_{{net_up_TCcloud}}) over the TC cloud area is given by:

where the (A(i,j)) as a function of latitude is the area of each pixel.

The TC center locations and TC intensities over all Ocean basins are provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS) TC best-track dataset21,22. TC intensity refers to the maximum sustained winds (kts) near the center of the storm. Note that all TCs reported in IBTrACS are used in this study.

TC solar elevation angle

The TC solar elevation angle indicates the angle between the sun at local noon and the horizon at the TC center and is calculated as:

where θs is the solar elevation angle at local noon, φ is the latitude of the TC center, and δ is the declination angle, which depends on the day of the year. The declination angle is given by:

where d is the number of days since January 1. The TC solar elevation angle depends entirely on the latitude of the TC center and the time of year.

TC days

The TC net radiation is influenced by the difference between SW radiation and LW radiation during a day. It is crucial to consider the distribution of TC clouds during both the daytime and nighttime since SW reflectance only occurs during daylight hours. Thus, in this study, we employ integer Local Solar Time (LST) days to ensure that analysis results do not include arbitrary “start” and “end” points of TCs, which could introduce bias and affect the net impact on the EEB10. Frequency of TC days was counted for each TC. Thus, if there are multiple TCs at the same time, the TC days may exceed 365.

TC size

The TC size refers to the TC cloud area at the local noon time. TC cloud area is calculated using the GPM_MERGIR-based TC cloud mask dataset4. Note that, 2,000,000 km2 is equivalent to a circular area with a radius of about 800 km being entirely covered with clouds.

Statistical analyses

The trend, b, is estimated using a linear least-squares regression. The error bars (denoted as err) of the trend are estimated by a two-tailed 95% confidence interval under the assumption that the residuals of the regression follow a normal distribution. The expression ‘b ± err’ represents the 95% confidence estimate of the trend value. The trend is tested for statistical significance for a null hypothesis that the trend is zero.

Responses