The interplay between positive lifestyle habits and academic excellence in higher education

Introduction

Academic performance is an important indicator of students’ educational progress and the quality of teaching, as well as a key outcome variable in exploring the higher education production function (Wang et al. 2015). It is important to study the factors that may positively or negatively impact undergraduate students’ academic performance, as the insights gained can be used to inform students about these influences, helping them make choices that minimize negative impacts and maximize positive ones. Various dimensions contribute to academic performance, including individuals, families, and schools (Shu et al. 2020). Previous studies in higher education have largely focused on the relationship between family and school backgrounds and academic performance (Aldhafri et al. 2020; Shu et al. 2020; Abbasi et al. 2023). However, in real-world settings, especially in China, undergraduate students are often geographically separated from their families. For many students, the transition from high school to college marks a pivotal period when they begin to make independent choices about diet and lifestyle. Compared to broader family and school factors, examining these choices at an individual level can provide more direct and specific insights. Therefore, understanding the relationship between lifestyle choices and academic performance at an individual level holds both theoretical and practical significance (Thiele et al. 2016).

According to the self-determination theory proposed by Miller et al. (1988), when an individual’s behavior is propelled by intrinsic motivation or autonomous factors rather than passivity, the behavior becomes more self-determined, fostering a sense of willingness and self-support for engagement (Deci and Ryan, 2008). Positive behavioral outcomes derive from autonomous individual actions (Credé and Kuncel, 2008). For instance, consistently having breakfast regardless of weather, following set schedules, and demonstrating strong time management skills all reflect individual autonomous behaviors. Importantly, these behaviors represent self-set goals that foster a harmonious blend of healthy lifestyle habits and outstanding academic performance (Burrows et al. 2017a; Khanal et al. 2021). Research indicates that adopting positive lifestyle choices, such as consuming fruits and vegetables, maintaining regular sleep patterns, engaging in sufficient physical activity, and frequently having breakfast, serves as positive predictors of academic performance (Bellar et al. 2014; Wald et al. 2014; Burrows et al. 2017b). In contrast, unhealthy behaviors like smoking or vaping, drinking alcohol, eating fast food, and working long hours are viewed as negative predictors of academic success (Arria et al. 2015; Reuter et al. 2021). The relationship between lifestyle habits and academic performance remains unresolved. Most studies on the impact of lifestyle habits have focused on children and adolescents. Although there is some evidence suggesting a relationship between positive lifestyle habits and academic performance among undergraduate students, much of this research relies on qualitative analyses and self-reported survey data. Therefore, there is a need for more research based on objective data to better understand the relationship within the undergraduate student population.

The purpose of this study is to build on previous research by utilizing a large set of objective data from higher education information databases. First, this study will employ data mining techniques and deep learning algorithms to create measurement indicators for students’ lifestyle habits (including eating, hygiene, and studying habits) and academic performance. Second, this study will explore whether positive lifestyle habits are associated with better academic performance. The full dataset comprised 3,123,840 instances of campus behavioral data from 3,499 students over four consecutive years (i.e., 2018–2022) at a university in northeastern China. Some data corresponded to the campus closure following the COVID-19 outbreak in January 2020. During this period, Chinese universities strictly controlled access to campuses and prohibited outside food deliveries. Data on eating in cafeterias, bathing, and studying in libraries further reflect students’ campus behaviors, and this reduction in external distractions enhances the research validity. The research findings provide practical insights for researchers to improve student management in educational institutions. Additionally, they complement existing big data analysis methods and offer a new perspective on educational data mining and its applications.

Literature review and hypotheses

Individual factors and academic performance

While the term “academic performance” is widely used, its definition remains unclear and lacks universal agreement (York et al. 2015). In the United States and many other countries, the grade point average (GPA), calculated based on course grades, is often used as a standard measure of academic performance (Şahin et al. 2018). Research on individual factors affecting students’ academic performance mainly focus on individual characteristics and individual behaviors. Among them, research on the factors influencing individual characteristics on academic performance is further divided into cognitive characteristics and non-cognitive characteristics (Hilbert, 2016; Abbasi et al. 2023). Cognitive characteristics such as cognitive ability, achievement goals, self-efficacy, and study-processing strategies can affect students’ academic performance (Leeson et al. 2008; Phan, 2010). The impact of cognitive characteristics on academic performance alone is insufficient. Therefore, scholars have started to explore characteristics that are not directly linked to students’ academic ability or academic development, which are called non-cognitive characteristics, such as age, gender and personality traits (Jishan et al. 2015; Zheng and Zhou, 2024).

Furthermore, current research on how individual behavior affects academic performance primarily emphasizes study habits and other lifestyle habits. Regarding study habits, existing studies have examined the influence of learning attitude, learning engagement and learning effort on academic performance (Martin et al. 2019; Aldhafri et al. 2020). To measure study habits, Western research often rely on self-reported data, such as the amount of time spent studying, strategies for self-regulated learning, and procrastination—the tendency to voluntarily delay tasks (Credé and Kuncel, 2008; Klingsieck et al. 2013; Svartdal et al. 2022). For objective indicators, library usage time and frequency can serve as indicators of learning effort, which reflect the diligence of students in learning (Stone and Ramsden, 2013). Furthermore, some studies explore the correlation between library use and students’ academic performance, believing that the more abundant library resources are, the more effective the cultivation of students’ critical thinking and the better their academic performance will be (Whitmire, 2002; Soria et al. 2013).

Some studies also focus on the impact of other lifestyle habits within individual behavior on academic performance. Kassarnig et al. (2018) extracted two behavioral characteristics of students on campus, orderliness and diligence, measured by entropy, and found a significant correlation between the regularity of campus life and academic performance. There are significant differences in healthy lifestyle habits between groups with low and high academic achievement, and developing healthy lifestyle habits can enhance promote educational outcomes for adolescent students (Vassiloudis et al. 2017). Students who engage in health-promoting behaviors, such as consuming fruits and vegetables, maintaining regular sleep patterns, getting sufficient physical activity, and eating breakfast frequently, tend to have better cognitive abilities and academic performance (Sigfúsdóttir et al. 2007; Alaraj et al. 2018; Xiang et al. 2023). However, existing research on lifestyle habits largely focuses on children and adolescents, while the transition to college is often accompanied by an increase in unhealthy behaviors, such as alcohol abuse, more frequent smoking, and irregular eating patterns (Reuter and Forster, 2021), which may affect students’ academic performance (Ruthig et al. 2011). Unhealthy behaviors such as smoking or vaping, consuming fast food, and working long hours are considered negative predictors of academic success (Arria et al. 2015; Reuter et al. 2021).

The goal of the university is to cultivate students’ rich professional knowledge and skills, and guide them to achieve all-round development in morality, intelligence, physique, and labor, and the basis for realizing this requirement is positive lifestyle habits (Trahar, 2014). Therefore, this study takes three of the most important daily behaviors of college students (eating, hygiene and studying) as the starting point, and focuses on exploring the correlation between different dimensions of lifestyle habits and academic performance.

Eating habits and academic performance

Eating habits are a key aspect of students’ lifestyles. It is important to explore how specific factors related to eating habits impact academic performance (Adolphus et al. 2015). Xie et al. (2018) have segmented students’ eating habits based on attributes such as timing, location, and spending. These characteristics have been quantified to measure students’ diligence and daily routines, uncovering the associations of each with academic achievement (Lien, 2007; Haapala et al. 2017; Reuter et al. 2021). The theory of consumption inertia posits that people tend to favor familiar products and services. Inertia also applies to eating (Kristo et al. 2020), including in terms of mealtime stability (e.g., eating breakfast around the same time every day) and preferred dining options (e.g., frequenting the same counter in a dining hall) (Burrows et al. 2017a). Skipping breakfast or engaging in short-term fasting has been associated with cognitive decline in students (Adolphus et al. 2015). Students also generally visit specific cafeteria counters (Hoyland et al. 2009), although the relationship between consistent dining hall–related choices and academic performance remains largely unknown. Eating habits reflect both the regularity of meals and the associated expenditures (Shu et al. 2020). To sum up, this study will investigate students’ eating habits from five dimensions, including breakfast frequency, dining counter stability, stability of dining time, stability of dining consumption and dining consumption level. Some studies have documented a positive correlation between consistently healthy eating habits and better academic performance. Specifically, greater dining regularity is associated with better academic outcomes and more consistent performance (Rampersaud et al. 2005; Taihua et al. 2022). We therefore propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Positive eating habits are positively correlated with undergraduate students’ academic performance.

Hygiene habits and academic performance

Positive hygiene habits contribute to physical well-being and may promote students’ cognitive and academic development. Such habits contribute to students’ self-management, self-service, and self-education (Lee and Loke, 2005). Existing research typically explores the correlation between hygiene and susceptibility to disease, as well as its impact on physical and mental health (Freeman et al. 2014). Some studies have considered specific domains, such as sleep hygiene, oral hygiene (Khanal et al. 2021), and hand hygiene, with respect to academic achievement. Students who maintain good personal hygiene typically exhibit greater classroom engagement and higher final grades (Carrión-Pantoja et al. 2022). Starting from the behavioral data of college students, this paper only examines the hygiene habits of students, including monthly bathing frequency and bathing time. We therefore propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Positive hygiene habits are positively correlated with undergraduate students’ academic performance.

Studying habits and academic performance

Studying habits encompass a set of behavioral patterns and cognitive approaches that students refine throughout their learning process. These habits profoundly influence academic performance and are the primary predictors of academic achievement. Positive studying habits can notably enhance students’ learning efficiency and academic outcomes (Jafari et al. 2019). These habits also prepare students to master the knowledge and skills needed to confront academic challenges confidently (Cerna and Pavliushchenko, 2015). Therefore, improving students’ studying habits is a major goal for educational institutions and parents. As students transition to college, they gradually become independent from both institutions and family support; developing positive studying habits can similarly lead to better academic performance (Cerna and Pavliushchenko, 2015). In the context of on-campus behavior, library usage serves as one indicator of undergraduate students’ studying habits. The correlation between students’ studying habits and their engagement with library resources has been well established (Stone and Ramsden, 2013). This study only examines undergraduate students’ studying habits, including the frequency and duration of their library visits, and the hypothesis is proposed as follows:

H3: Positive studying habits are positively correlated with undergraduate students’ academic performance.

Data and method

Data

Undergraduate students generate vast amounts of behavioral data every day through various university systems. This student behavior data can be analyzed to assess academic performance, study habits, and other lifestyle habits. The data examined in this study comes from the campus system database of a university in Northeast China, which records students’ basic information, academic performance, as well as detailed data on daily transactions and library visit logs. This study extracted four types of data from the campus system database of the university. First, the basic student information includes each student’s name, gender, student ID, college, major, enrollment year, hometown, and ethnicity. Second, academic performance data consists of course names, grades, and rank. Third, lifestyle transaction data includes categories of spending, locations, service counters, payment methods, timestamps, transaction amounts, remaining balances, and recharge amounts. The spending categories encompass dining in cafeterias and bathing expenses. Fourth, the library access logs provide accurate entry and exit times, as well as visit frequencies. Data use complies with privacy requirements and standards, and data involving students has been desensitized. All data were preprocessed to remove duplicate records and standardize the formatting. Students’ academic performance data were also normalized to account for score variations across disciplines and majors.

The dataset used in this study contains 3,123,840 records of on-campus behavioral data from 3,499 undergraduate students collected between 2018 and 2022. Roughly 78% of the students were men, and the remaining 22% were women. This study was conducted within the College of Engineering, where students’ gender ratio is markedly imbalanced. The research sample consisted of 1676 students aged 22 and 1445 students aged 23 (48% and 41% of the dataset, respectively). A subset of 398 undergraduates represented ethnic minorities, constituting 11% of the sample. Most students (71%) were members of the Communist Party of China (CPC). The average grade point average (GPA) was 80.095 points, with a standard deviation of 9.373. This distribution closely resembled a normal one in that it mirrored college students’ actual academic performance patterns. This sample therefore possessed a reasonable structure, approximated real-world proportions, and was highly representative. Additionally, the dataset corresponds to the campus closures following the outbreak of COVID-19 in January 2020. During this period, universities in China strictly controlled access to campus and prohibited outside food deliveries. The data on eating in cafeterias, bathing, and studying in the library largely reflect students’ on-campus behaviors with reduced external distractions. These factors collectively support the study’s credibility and reliability.

Measures

Academic performance (GPA) is a key metric of educational quality and a quantifiable outcome of students’ achievement. This measure normally refers to GPA in higher education settings, which is calculated by weighting the grades of individual courses according to their credit hours (Wang et al. 2015; Zeek et al. 2015).

This study refers several independent variables from Shu et al.’s (2020) dining model. Aspects of interest included students’ Mealtime stability coefficient, Early rising coefficient, Restaurant counter selection, Restaurant consumption level, and Restaurant consumption stability. These variables were used to define a range of eating habit indicators, facilitating a more systematic analysis of students’ consumption behavior. Several other factors (e.g., Average bathing frequency, Average bathing time, Average library arrival frequency, and Average study duration) were assessed based on their relative intensity in Applied Statistics. The specific calculations for all independent variables are shown in Table 1.

Control variables included Gender (woman = 1 and 0 otherwise), Ethnicity (Han = 1 and 0 otherwise), Age, and Political Affiliation (CPC membership = 1 and 0 otherwise). These characteristics were integrated to control for potential confounding factors that might affect academic performance. This approach ensured a more precise evaluation of how students’ lifestyle habits influence their academic achievement.

Model training

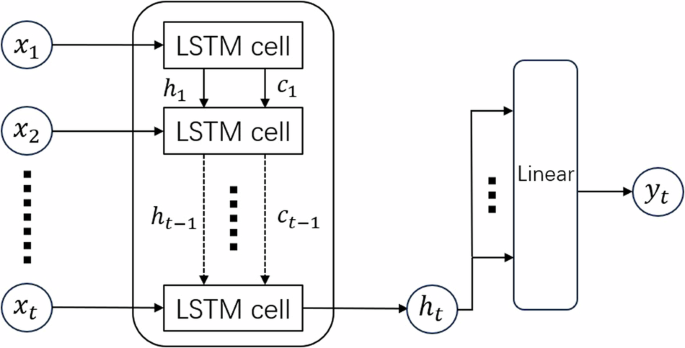

In this study, we use an LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) model to process and compute indicators of students’ historical eating habits. The model is implemented in Python using a custom script based on the Torch library, a widely used framework for deep learning. The Torch library provides flexibility in designing and training custom LSTM models tailored to specific tasks. As a type of recurrent neural network (RNN) structure, LSTM is particularly well-suited for handling time series data. Compared with traditional RNN, the LSTM introduces input gates, forget gates, output gates, and a cell state, which enable LSTM to better handle long-term dependencies in sequences (Graves and Schmidhuber, 2005). The specific process is shown in Fig. 1.

The architecture of the LSTM model.

At each time step t, the LSTM receives an input variable xt, which includes behavioral features like meal time and location at that moment. To make these features suitable for model processing, one-hot encoding is applied, representing various categories of times (breakfast, brunch, lunch, afternoon tea, dinner, and late-night snack) and meal locations as separate dimensions. As a result, the input variable’s dimension expands to 404, encompassing the categorical features for all time points. One-hot encoding is defined here as follows: typically, categorical features like meal locations might be represented by numbers (1 to n), yet since there is no inherent ordering or magnitude relationship between these categories, they are converted into one-hot encoded variables to separate them effectively. Each category is represented by an N-bit register, where only one bit is active at any point, which not only addresses the issue of implied ordering in categorical data but also enriches the feature space. This added dimensionality helps the model better differentiate distinct behavioral patterns.

The LSTM controls the flow of information through three internal gates—forget gate, input gate, and output gate—to effectively manage both long-term and short-term dependencies in a sequence. The forget gate determines which information from the previous hidden state ({h}_{t-1}) should be retained or discarded, filtering historical information that is relevant to the current time step. The input gate receives the current input xt and decides what new information should be stored in the LSTM cell. Finally, the output gate generates the current hidden state ht based on the information within the cell and produces the model’s prediction yt at that time step.

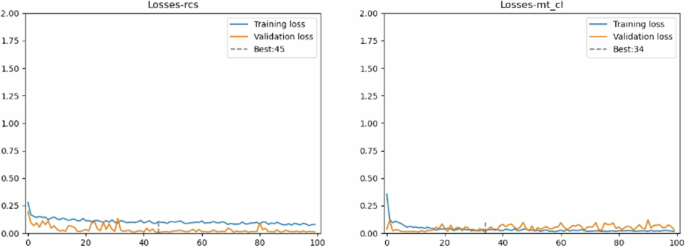

In supervised learning, the evaluation metric is known as the loss value, which quantifies the model’s error. In this study, the LSTM model was used to calculate the variables related to eating habits, and the training loss for selected variables is shown in Fig. 2. The training and validation loss of both models drop sharply at the beginning and then stabilize at lower levels. The optimal validation loss appears around the 45th and 34th iterations, indicating that the LSTM model has achieved a satisfactory performance at these points.

Each line represents the loss value over epochs for a different model, with no evidence of overfitting or underfitting observed.

Analytic approach

A multiple regression model was created to test H1–H3 regarding undergraduate students’ lifestyle habits and associated effects on academic performance. The following regression equations applied:

where YGPA is the student’s academic performance (GPA); Xhabit is the student’s eating habits, hygiene habits and studying habits; and Gender, Ethnicity, Age, Political Affiliation are control variables. ε is the random disturbance term; β1 denotes the parameters to be estimated. The regression analyses were implemented using custom code written with the Statsmodels library, a widely used Python module that facilitates the estimation and analysis of various statistical models.

Results

Descriptive findings and factor analysis

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis results for all variables. From the results in Table 2, we can see a high correlation among the internal indicators of eating habits, hygiene habits, and studying habits. To eliminate the effect of multicollinearity, we will perform factor analysis on the five variables of eating habits and combine the variables of hygiene habits and studying habits into a single representative variable for each.

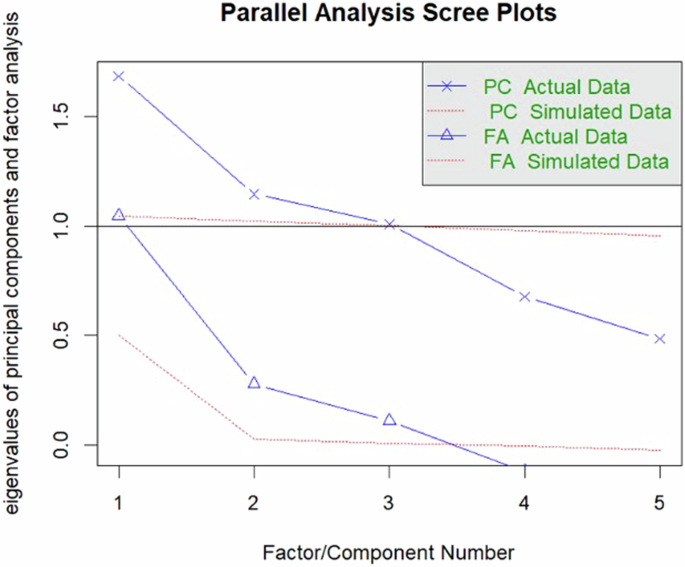

First, we conducted a parallel analysis on the five variables of eating habits to determine the number of factors. The results are shown in Fig. 3. Based on these results, we selected factors where the actual data’s eigenvalues are greater than those of the simulated data, ultimately deciding to retain three factors for eating habits.

Parallel analysis scree plots of the five variables related to eating habits (students’ mealtime stability coefficient, early rising coefficient, restaurant counter selection, restaurant consumption level, and restaurant consumption stability) calculated using LSTM models.

Table 3 presents the factor analysis results for eating habits. Three loading coefficients were particularly important within the factor component rotation matrix for eating habits. The Early rising coefficient and Restaurant counter selection on Common Factor 1 (i.e., Consumption Inertia) had notable magnitudes at 0.86 and 0.85, respectively. The findings suggest that both variables heavily relied on the first common factor. The consistency in students’ early rising behavior and restaurant counter selection reflected their dedication to upholding dining quality. Such actions imply clear resolve and self-regulation. The concept of consumption inertia emerged from consumer behavior analysis, describing consumers’ tendency to repeatedly choose familiar products and services. These choices are generally resistant to external influences when individuals exercise a certain level of rational control. This theoretical framework suggests that consumers gradually develop preferences and consumption patterns through persistent and repeated use—a phenomenon that closely aligns with the observed characteristics of Common Factor 1.

The loading coefficients for the Mealtime stability coefficient and Restaurant consumption stability on Common Factor 2 (i.e., Meal Regularity) were also noteworthy at 0.89 and 0.64, respectively. Due to the consistency in mealtime and meal consumption behaviors, this factor reflects students’ inclination to fulfill their dining needs. These patterns’ stability implies greater regularity in students’ eating habits. The loading coefficient for Common Factor 3 (i.e., Dining Consumption Level) was high at 0.94 and characterized the extent of students’ dining consumption.

The primary components extracted from eating habit data (i.e., Consumption Inertia, Meal Regularity, and Dining Consumption Level) accounted for 30%, 25%, and 22% of the information within the full dataset, respectively. This cumulative contribution rate of 77% indicated that the extracted principal components encapsulated 77% of information contained in the original variables. The dimensionality reduction was thus quite effective. In summary, factor analysis demonstrated that students’ eating habits could be succinctly represented by three factors.

Second, factor analysis was conducted separately on the indicators related to hygiene habits and studying habits. The common factor reflecting students’ Average bathing frequency and Average bathing time was named “Hygiene Habits.” The common factor involving students’ Average library arrival frequency and Average study duration was labeled “Studying Habits.”

Association between lifestyle habits and academic performance

Table 4 lists the results of main empirical analysis on the identified common factors. As shown in Column (1) of Table 4, female students, ethnic minority students, younger students, and Communist Party members tend to have higher grades. The results in Column (2) indicate that consumption inertia has a significant positive impact on students’ academic performance, showing a strong positive correlation (β = 0.101, p < 0.001). This finding suggests that when students engage in frequently repeated behaviors, these habits generally arise from long-term practice (i.e., the actions are intrinsically motivated and internally driven). This behavioral pattern is referred to as “consumption inertia.” Since not all students will consistently adhere to such behavior, especially in response to external changes, those who demonstrate persistence (i.e., those with higher consumption inertia) typically exhibit strong willpower, which is commonly associated with higher academic achievement.

The results in Column (3) indicate that eating regularity has a significant negative impact on students’ academic performance (β = −0.148, p < 0.001). This result contradicts the traditional view that regular meal consumption is associated with better academic performance (Burrows et al. 2017a; Logi et al. 2010). However, empirical evidence suggests that students who are highly invested in their studies may sometimes overlook daily routines like regular meals, prioritizing research or projects over meal and sleep schedules. On the contrary, students with more leisure time tend to maintain regular eating habits. This creates a paradox where students with higher meal regularity may not be as focused as others on academic pursuits. Additionally, meal schedules can interrupt sustained study sessions, which may explain the negative correlation between meal regularity and academic performance.

The results in Column (4) show that students’ dining consumption levels have no significant impact on academic performance (β = −0.001, p > 0.05). This may be due to two main reasons: first, as long as students’ dietary needs meet basic nutritional requirements, the level of consumption might have little effect on academic performance. Second, the similar price levels across various counters in the school cafeteria make it challenging to accurately distinguish students’ consumption levels. In summary, Hypothesis H1 is not fully supported.

The results in Column (5) show that hygiene habits have a positive impact on academic performance (β = 0.066, p < 0.001). Bathing promotes metabolism, strengthens the immune system, and reduces the likelihood of illness. It also helps to guarantee stable, continuous learning. Additionally, bathing can regulate the nervous system by reducing stress, thereby easing study-related fatigue and improving students’ mental state and efficiency. Thus, positive hygiene habits are significantly correlated with academic performance, supporting Hypothesis H2.

The results in Column (6) show that studying habits also have a positive impact on academic achievement (β = 0.198, p < 0.001). The library, with its quiet, comfortable environment and wealth of resources, is an ideal place for learning. Students who used the university library to read literature, obtain information, and study intensely seemed to benefit academically. The depth and breadth of their learning increased accordingly. In general, studying in the library helps cultivate effective habits such as active reading, summarizing, critical thinking, and creativity. These positive studying habits are likely significantly associated with improved academic performance, supporting Hypothesis H3.

Robustness check

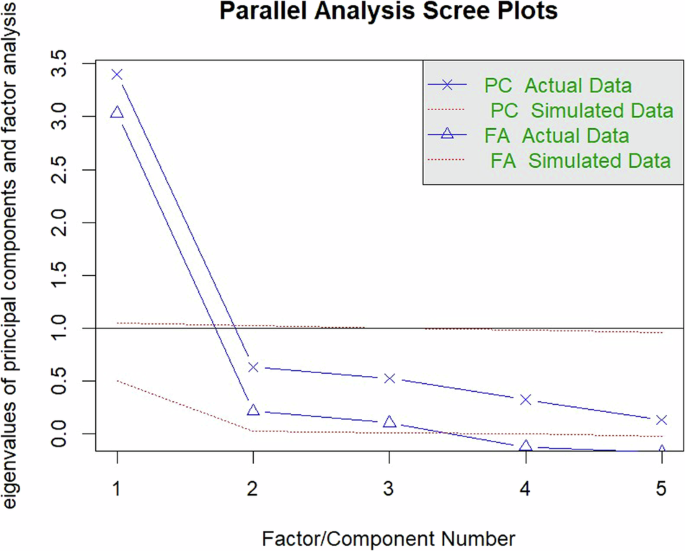

To ensure the robustness of the empirical results above, this study generates two subsamples from the dataset constructed using the LSTM model: one is based entirely on actual student data, while the other consists of values calculated by the LSTM model. Robustness checks were performed using this subsample approach. According to the parallel analysis scree plots in Fig. 4, selecting three common factors for eating habits is reasonable and aligns with the main effect results.

Parallel analysis scree plots of the five variables related to eating habits (students’ mealtime stability coefficient, early rising coefficient, restaurant counter selection, restaurant consumption level, and restaurant consumption stability) calculated using the full sample.

The complete dataset was used in regression analysis, with repeated runs before the empirical analysis. The main results in Tables 5 and 6 are consistent with those in Tables 3 and 4, with no significant changes in the significance levels or positive/negative correlations of the variables. Therefore, the findings in the main effects are considered reliable.

Discussion

This study proposed a student behavior characteristic analysis framework combining multiple linear regression with LSTM neural network models. Lifestyle habits were discussed vis-à-vis academic performance by examining students’ eating habits, hygiene habits, and studying habits. The findings extend research on lifestyle factors and academic performance based on campus big data. The main results are as follows. First, breakfast behavior and counter selection stability demonstrate characteristics related to consumption inertia, which are significantly associated with students’ academic performance. Students who exhibit consumption inertia tend to have greater willpower, which is often linked to better academic outcomes. This supports consumption inertia theory and broadens the theory’s application into the field of education. Second, in contrast to the traditional belief that meal regularity positively correlates with academic performance, this study indicated that mealtime stability and restaurant consumption stability had significant negative impacts on academic performance—at least in the higher education context. This finding challenges the notion that regular eating habits lead to better performance (Logi et al. 2010; Burrows et al. 2017b). Rather, students with excellent academic performance seem to prioritize their studies to the detriment of meal regularity. Students who eat highly regularly may have an abundance of free time that does not necessarily enhance academic achievement. Third, the impact of dining consumption level on students’ academic performance was statistically insignificant. The limited impact of student consumption levels on academic performance may be due to the fact that basic nutritional needs are being met, and the similar pricing across university cafeteria options makes it difficult to distinguish consumption levels. Fourth, hygiene habits and studying habits demonstrated positive and significant effects on academic performance: frequent bathing and regular library visits were specifically associated with better academic performance, suggesting that personal care routines and a structured study environment may contribute to improved focus and cognitive function. In summary, lifestyle habits collectively appear to have a significantly positive relationship with students’ academic performance.

Furthermore, this study emphasizes the significance of cross-cultural and cross-border approaches. While our study was conducted within the context of higher education in China, the findings presented herein may possess broad applicability. In various countries, particularly across Asia, educational systems typically prioritize the cultivation of students’ discipline and self-discipline (Piel, 2019). Should students cultivate favorable habits pertaining to work-rest balance, dietary patterns, and study routines, the resultant self-discipline and consistent lifestyle can contribute to heightened learning efficiency and concentration, often translating into enhanced academic performance.

Notably, this study highlights the positive influence of lifestyle habits on academic performance, offering valuable insights for shaping effective educational policies and interventions. Global disparities in educational and economic development mean that many populations may lack awareness or access to resources for adopting healthy lifestyle habits. To address this, higher education policymakers and educators could consider implementing policies and programs that encourage healthier lifestyles, as these may enhance academic outcomes. Specifically, higher educators could consider developing new health-related curricula to help educate students to adopt healthy, hygiene lifestyles. In addition, educators can organize seminars and after-school activities to plan a variety of free intervention programs for students to improve eating habits (for example, developing healthy and regular eating habits), hygiene habits (bathing regularly), and self-directed studying habits.

Conclusion

This research has presented an in-depth analysis of students’ behavior using campus big data along eating, hygiene, and studying dimensions. Big data algorithms and technologies were adopted to introduce campus data mining into the education field. To address the complexity of student behavior and the difficulties of feature extraction, a model integrating the LSTM method with empirical analysis was introduced. This study utilizes a neural network approach to identify trends in student behavior characteristics, effectively addressing the issue of dimensional comparability caused by subjective definitions in existing research (Shu et al. 2020). By analyzing college life consumption data, library access logs, and academic performance data, the study develops a detailed behavioral analysis framework for assessing university students’ lifestyle habits. Empirical results indicate that the development of undergraduate students’ eating habits, hygiene habits, and studying habits is closely related to their academic performance. The proposed framework can help colleges and universities better understand student behavior, particularly how lifestyle habits impact academic performance. This framework provides theoretical guidance for student affairs and educational managers by addressing a key gap in analyzing student behavior through campus big data.

Despite its novelty, this study has several limitations. First, the primary factors influencing undergraduate’ academic performance were examined mainly through self-reported behaviors, which may have led to incomplete indicators and overlooked aspects. Additionally, the selected metrics likely did not capture all attributes contributing to academic success. Second, due to constraints within the campus big data platform, it was impossible to capture all students’ behaviors on campus. The sample was also confined to a first-tier university in China; findings may not generalize to other higher education settings. Relatedly, first- and second-tier universities are distinct in this country (Du, 2023). Subsequent research could investigate the causal effects of higher education stratification. Third, we encourage future studies to replicate and validate our findings in diverse cultural contexts to bolster the robustness of our results and foster international knowledge exchange and collaboration. Conducting cross-cultural comparative research will facilitate a deeper comprehension of the intricate relationship between students’ lifestyle habits and academic performance. Moreover, it will offer valuable insights and recommendations for educational reform and policy formulation on a global scale.

Responses