The intersection of aging and estrogen in osteoarthritis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common chronic joint diseases and is characterized by cartilage degradation, joint inflammation, and bone remodeling, which leads to joint pain, swelling, stiffness, and ultimately loss of joint function1. In the USA, OA affects over 34 million adults and costs over $136 billion annually2. These numbers are projected to substantially increase given the aging population. Multiple factors like genetics, prior injury, female sex, and obesity can contribute to OA risk, but aging remains a ubiquitous risk factor which has impact on the gross mechanical properties of tissues and at the molecular level of cells3. Notably, the most vulnerable cohort for developing OA are post-menopausal women with prevalence rates nearly twice those observed in men of comparable age4,5.

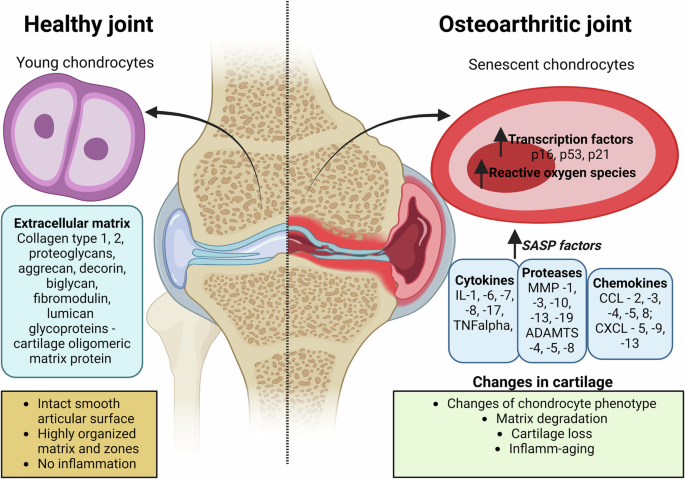

Aging research has highlighted that chondrocytes, the primary cell type within articular cartilage, acquire changes linked to cellular senescence such as telomere shortening, increased cell death, elevated senescence-associated-β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) activity, tumor protein p53 (p53)6, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 A (p21CIP1), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2 A (p16INK4A)7, various cytokines8, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (Fig. 1)9,10. Senescent cells remain metabolically active and secrete a mix of molecules termed the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)11,12. This involves the release of various cytokines such as interleukins -1, -6, -7, -8, -17 (IL -1, -6, -7, -8, -17), oncostatin M (OSM), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα); proteases including MMP -1, -3, -10, -13, and a disintegrin, and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs -4, -5, -8 (ADAMTS -4, -5, -8)8,12,13,14, SASP can cause local and systemic inflammation and disrupt tissue integrity. Levels of SASP factors increase systemically with aging in people with OA15,16. These age-related cartilage changes likely promote OA development17. Several review articles have examined the role of chondrocyte senescence in the initiation and progression of OA18,19.

In the healthy joint, young chondrocytes maintain the extracellular matrix composed of collagen type -1, -2, proteoglycans (aggrecan, decorin, biglycan, fibromodulin, lumican), and glycoproteins (cartilage oligomeric matrix protein). The articular surface is smooth and intact, with a highly organized matrix structure and no signs of inflammation. The osteoarthritic joint displays senescent chondrocytes with increased expression of transcription factors including cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2 A (p16ink4a), tumor protein p53 (p53), cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 A (p21cip1) and reactive oxygen species. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) factors are elevated, including interleukins -1, -6, -7, -8, -17 (IL -1, -6, -7, -8, -17), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), matrix metalloproteinase -1, -3, -10, -13, -19 (MMP -1, -3, -10, -13, -19), A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase with Thrombospondin Motifs -4, -5, -8 (ADAMTS -4, -5, -8); C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand -2, -3, -4, -5, -8 (Ccl -2, -3, -4, -5, -8) C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand -5, -9, -13 (Cxcl -5, -9, -13). These molecular changes lead to alterations in cartilage, including changes in chondrocyte phenotype, matrix degradation, cartilage loss, and inflammation-associated aging.

OA is more prevalent in women compared to men, especially after the menopause20,21,22. Cartilage is an estrogen-sensitive tissue, showing sex differences in cartilage degeneration and repair23,24. With aging, cartilage undergoes various changes including reduced cellularity and extracellular matrix content followed by thinning and weakening25. During the menopause, women experience a decline in estrogen levels26. Radiographic knee OA is three times more common in women aged 45-64 years old versus men of the same age group21. The significant rise in OA prevalence among postmenopausal women suggests a connection between OA and loss of estrogen. This association implies a potential chondro-protective role by estrogen against the development of OA27,28.

The link between aging, estrogen, and OA is complex and involves multiple factors. While we know aging and estrogen impact the development of OA, we do not fully understand how they contribute. This paper reviews the impact of aging and estrogen deficiency on the onset and development of OA, focusing on transcriptomic changes that provide insights into key genes and pathways involved in disease progression.

Methods

A literature search was conducted to identify relevant publications on PubMed between 2012 and 2024. Searches included the terms “age related osteoarthritis and RNA sequencing” or “estrogen and age-related osteoarthritis OR estrogen and chondrocyte senescence” titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, and full text articles were reviewed. Data from papers were extracted. Reference lists were checked to identify any additional relevant literature, which was also reviewed.

Results

Hallmarks of aging in OA

OA is a globally prevalent and debilitating chronic joint disease, and a leading cause of pain and disability among the elderly29,30. Although defining OA remains heterogeneous across epidemiological studies, age is recognized as the single greatest risk factor for its development31. Aging is a natural biological process characterized by the progressive deterioration of protective mechanisms that normally repair cellular and tissue damage throughout the body32. This decline increases vulnerability to diseases and raises mortality risk33,34,35. A hallmark of aging represents a distinct biological change that occurs during normal aging, correlates with decreased physiological function, and contributes to age-related diseases32,36. Researchers have established a framework of aging hallmarks to understand how aging contributes to age-related diseases37,38. The original nine hallmarks include (i) genomic instability, (ii) telomere attrition, (iii) epigenetic alterations, (iv) loss of proteostasis, (v) deregulated nutrient sensing, (vi) mitochondrial dysfunction, (vii) cellular senescence, (viii) altered intercellular communication, and (ix) stem cell exhaustion37. These hallmarks represent fundamental biological processes involved in joint degeneration. Recent scientific advances have identified five additional aging characteristics that complement the original hallmarks: compromised autophagy, dysbiosis (microbiome disturbances), splicing dysregulation, inflammaging (chronic low-grade inflammation) and altered mechanical properties38,39.

Several studies have extensively reviewed the roles of these hallmarks in OA progression11,30,40,41,42. Notably, Dieckman et al. 40 explored the intersection of these hallmarks with pathological changes observed in joint tissues during OA. They emphasize that the hallmarks are not isolated phenomena but are instead highly interconnected, with cellular senescence emerging as a central mediator that initiates cellular dysfunction and drives OA pathology. Similarly, He et al.41 systematically discussed the pathological roles of aging hallmarks as they relate to OA onset and progression, summarizing the available updates on experimental and potential clinical approaches for treating OA through targeting the proposed aging hallmarks.

Human studies showed age-related decreases in cartilage cellularity and loss of extracellular matrix components particularly aggrecan, the major proteoglycan of cartilage43,44,45,46. Such changes contribute to cartilage thinning, mechanical weakening and ultimately loss of cartilage function31,47,48,49. The aging extracellular matrix of cartilage demonstrates increased glycation end-products (AGEs) increases cartilage stiffness, while reduced proteoglycan synthesis and altered collagen structure compromise extracellular matrix integrity40,44. AGE accumulation alters the biomechanical properties of the tissue and is associated with reduced chondrocyte anabolic activity43,50. Loeser et al. 46 provided a comprehensive summary of how aging affects the cartilage matrix in OA. Roelofs and De Bari51 reviewed the role of age-related changes including cartilage matrix stiffening, cellular senescence, mitochondrial dysfunction, metabolic dysfunction, and impaired autophagy. Studies suggests that partially or fully mitigating these hallmarks can reduce the degenerative processes associated with aging and OA18,41,50,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. Despite this promising framework, the intricate interplay between these hallmarks remains incompletely understood. RNA sequencing (RNA seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying OA by providing detailed analysis of gene expression patterns. In the following chapter, we examine the transcriptomic changes involved in aging-related processes in OA.

Transcriptomic changes with aging in OA

Most studies have focused on investigating general transcriptomic changes associated with post-traumatic OA rather than specifically examining aging-related transcriptomic changes60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76. It is important to note that the majority of total knee arthroplasties are related to post-traumatic OA cases, with fewer being idiopathic OA in nature77,78,79. Post-traumatic OA accounts for up to 12% of all arthritis cases in clinical settings, resulting in most clinical samples analyzed being derived from this subset77,80,81. While analyzing idiopathic OA samples would provide the most direct approach to understanding the impact of aging in OA development, the scarcity of such samples has led researchers to use samples from post-traumatic OA as an alternative for studying the impact of aging.

Age-related transcriptomic changes of rodent cartilage

There is a limited number of publications that investigate the impact of aging on the development of OA (Table 1). In this sub-section, we cover cartilage transcriptomic changes in rodent models of OA. Loeser et al. 82 compared gene expression in joint tissues from 12-week-old mice and 12-month-old mice. They demonstrated that expression of IL -6, IL -33, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand -13 (Cxcl-13), C-C motif chemokine ligands -5, -8 (Ccl -5, -8), were significantly upregulated and type IX and type II collagen, matrillin 3, and hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 (Hapln1) were downregulated in the old mice compared with the young mice. Similarly, Sebastian et al. 83 examined OA changes in mouse knees from 10 to 95 weeks old. In agreement with Loesser at al., their RNA seq data revealed that old mice had increased expression of IL-6 and IL-33, and increased chemokine expression (Ccl -3, -4, -5, -8, Cxcl -5, -9, -13) while expression of transcription factor SRY-related HMG-Box transcription factor-9 (Sox-9), collagen type II alpha 1 chain (Col2a1), and aggrecan core protein (Acan) were reduced. Iijima et al. 84 elucidated how age-induced stiffening of the extracellular matrix impacts the regulation of α-Klotho, a multifunctional protein associated with anti-aging processes. A significant finding is that age-related stiffening of the extracellular matrix results in the epigenetic suppression of α-Klotho expression in chondrocytes, facilitated by promoter methylation and increased recruitment of DNA methyltransferase-1 (DNMT-1). Their findings revealed a mechanism through which changes in the extracellular matrix associated with aging can detrimentally affect cartilage health.

Age-related transcriptomic changes of human cartilage

Comparisons of OA cartilage from older individuals to healthy cartilage from non-OA knees are uncommon because it is difficult to obtain biopsies of healthy cartilage. As a result, intact cartilage from non-weight bearing areas of joints with post-traumatic OA is often used instead. It is debatable whether this serves as an adequate control. Lewallen et al. 85 reported that OA development involves whole-joint changes that trigger molecular responses even in undamaged cartilage within the joint. Similarly, differences were found in gene expression between traumatic and degenerative meniscus tears86. However, in contrast, Wang et al. 87 found no substantial differences in gene expression between healthy cartilage samples with localized lesions and those without lesions, while OA cartilage displayed significantly distinct gene expression patterns.

Asik et al. 88 analyzed gene expression profiles in damaged and undamaged cartilage from the same joints undergoing matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation. Their aim was to compare the gene expression patterns of in focal lesions and healthy cartilage areas within the same joint of the patients. They observed elevated expression levels of (i) growth factors, including transforming growth factor, beta induced (TGFβI), growth differentiation factor (GDF6), and insulin-like growth factor (IGF1); (ii) transcription factors, such as hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF1α), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 (TIMP2), EP300-interacting inhibitors of differentiation 1 and 2 (EID1, EID2), nuclear receptor coactivator 3 (NCOA3), neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 (NBR1), SP100 nuclear antigen (SP100), and heat shock protein 90 alpha family class A member 1 (HSP90AA1); (iii) cytokine IL-11; (iv) matrix-degrading proteases, including MMP -2, -9, -13, -14, and ADAMTS-12; and (v) extracellular matrix proteins, such as Col1a1 and Col4a1 in the damaged cartilage. In contrast, the expression of TIMP-4 and Acan was lower compared to non-weight-bearing, undamaged cartilage. Dunn et al. 89 found a decrease in SOX -6, -9, Collagen Type XI Alpha 2 Chain (Col11a2), Collagen type IX alpha -1, -2, -3 chain (Col9a -1 -2 -3), Acan, and Hapln1, alongside an increase in Col1a1, COMP, Fibronectin 1 (FN1), and proteoglycans associated with fibrosis specifically within damaged cartilage in osteoarthritic joints. Notably, minimal levels of IL -1α, -1β, -6, OSM, and TNFα were detected. Furthermore, network analysis identified a core of four transcription factors — FOS like-1 (FOSL-1), aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), E2F transcription factor-1 (E2F-1), and forkhead box-M1 (FOX-M1) — that functioned as a central hub connecting various cellular regulatory changes.

Fisch et al. 74 conducted RNA seq to compare normal cartilage (5 female and 13 male donors) and osteoarthritic cartilage (12 female and 8 male donors). Their analysis revealed 15 significantly dysregulated pathways in OA, with the most notable alterations found in extracellular matrix -related pathways, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K-Akt), HIF-1, Fox-O, and circadian rhythm pathways. Through integrative data analysis, they prioritized transcription factors based on differential expression, enrichment for binding sites in differentially expressed genes, and the number of connections within a cartilage-specific subnetwork. This approach identified eight key transcription factors — Jun Proto-Oncogene (JUN), Early Growth Response 1 (EGR1), JunD Proto-Oncogene (JUND), Fos Like 2, AP-1 Transcription Factor Subunit (FOSL-2), Myelocytomatosis Proto-Oncogene (MYC), Kruppel-Like Factor 4 (KLF4), REL Associated Proto-Oncogene (RELA), and Fos Proto-Oncogene (FOS) — highlighting their potential roles in OA pathophysiology. Swahn et al. 90 compared healthy and osteoarthritic human cartilage and meniscus. They demonstrated the expansion of senescent cell subsets in both cartilage and meniscus in OA. This subset displayed extracellular matrix dysregulation mediated by fibroblast activation protein (FAP) and MMP-9 activity, along with upregulation of fibrotic genes and the senescence-associated transcription factor zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1). They confirmed ZEB1 overexpression directly increased the senescence marker p16 INK4A. Their integrative analysis also revealed the pathogenic subset as the primary recipient of transforming growth factor β signaling, contributing to its fibrotic phenotype.

Recent studies have demonstrated that RNA isolation directly from cartilage tissue provides a more accurate representation of the native tissue’s transcriptome profile91,92. When chondrocytes are isolated from their native extracellular matrix composition, significant alterations in gene expression can occur and chondrocytes isolated from fresh tissue and expanded in culture do not entirely mimic the tissue’s pathophysiological state93,94. While chondrocytes exist in a stationary physiological state in vivo, they undergo active proliferation in vitro and are at risk of de-differentiation95. So far, we have discussed transcriptome changes observed directly in cartilage tissue. In this paragraph, however, we will focus on transcriptome changes within isolated chondrocytes rather than the entire cartilage tissue. It is also essential to understand the transcriptome of chondrocytes in 2D monolayer cultures or 3D in vitro models, as numerous in vitro studies are performed at the cellular level96,97. Consequently, several studies have focused on examining the transcriptome of chondrocytes isolated from human cartilage to better characterize cellular behavior under experimental conditions. For instance, Atasoy-Zeybek et al. 98 conducted a pilot study comparing healthy and osteoarthritic cartilage by culturing chondrocytes from both groups through serial passages until they reached their replicative senescence, followed by bulk RNA seq. Their analysis of differentially expressed genes revealed a consistent downregulation of Col2a1 and Acan, along with an upregulation of MMP-19, ADAMTS -4, and -8 in late passage chondrocytes across all samples. Notably, components of the SASP such as IL -1α, -β, -6, -7, p16INK4A, and CCL-2 exhibited significant upregulation in late passage chondrocytes originally isolated from osteoarthritic samples. Gao et al.99 studied inflammation-responsive chondrocyte populations using single-cell RNA seq of IL-1β-stimulated articular chondrocytes. They initially identified two distinct cell clusters with heterogeneous expression patterns that evolved over time into two terminal clusters. One of these clusters displayed an OA phenotype and proinflammatory traits. Genes associated with this transformation were involved in TNF signaling through Nuclear Factor Kappa B Subunit 1 (NFκB), up-regulated Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) and IL2/STAT5 signaling, apoptosis pathways, and ROS pathways.

Utilizing gene expression omnibus datasets

Several studies have utilized gene expression omnibus (GEO) datasets to explore the relationship between senescence and OA. Weng et al. 100 investigated the role of GDF15 in OA using the GEO data set GSE176308. They found that GDF15 drives both senescence and angiogenesis in OA. Furthermore, they showed that GDF15 induced the SASP phenotype through mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 (MAPK14) activity in chondrocytes. Additionally, treatment with a GDF15 neutralizing antibody substantially decreased the presence of senescent cells and angiogenesis in the synovial tissue of rats with OA induced through articular cartilage damage in vivo. Guang et al. 101 utilized GEO datasets (GSE169454 and GSE152805) and the meta-VIPER algorithm. They identified 16 protein-activity-based chondrocyte clusters with a novel subpopulation of chondrocytes (cluster 3) and observed a significant association between key proteins (N-Myc downstream-regulated gene 2 (NDRG2), testis-specific Y-encoded-like protein (TSPYL2), and high mobility group box 2 (HMGB2) and OA. These proteins are predicted to play critical roles in regulating chondrocyte homeostasis and combating chondrocyte senescence. Yoshimoto et al. 102 utilized GSE104782 and GSE169454 data set and investigated the potential relationship between cellular senescence signaling and the glycosylation pathway in OA. They found that the expression levels of the polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase (GALNT) family, particularly GALNT16 being the top regulated gene along with significant upregulation of GALNT1, GALNT2, GALNT7, and GALNT15, are essential for the biosynthesis of O-Glycans at an early stage and are significantly upregulated in OA chondrocytes. Boone et al. 103 explored senescence-associated genes from OA patients using mRNA-seq datasets104 and a generated metabolic dataset from overlapping blood samples. They identified two cellular senescent endotypes: Endotype-1 enriched in cell proliferation pathways with expression of FOXO4, RB transcriptional corepressor like 2 (RBL2), and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (CDKN1B, encoding p27), and elevated plasma histidine; Endotype-2 enriched in inflammation pathways with IL-6, MMP -1, -3, vascular endothelial growth factor C (VEGFC) expression, and associated with elevated serum lipids, cholesterol, and fatty acids.

Aging-related gene networks in OA using RNA sequencing data

It is important to note that several publications discovered certain aging-related genes in OA development utilizing RNA seq technology in their study. For instance, Ji et al. 105 demonstrated that Sirtuin 6 (Sirt6) plays a crucial role in mitigating chondrocyte senescence by inhibiting the Janus kinase (JAK), signal transducer of activation (STAT), and IL-15/JAK3/STAT5 pathways in OA. Their study revealed that intra-articular injection of adenovirus-Sirt6 significantly alleviates OA induced by surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM). Sirt6 interacts with and deacetylates STAT5, preventing its IL-15/JAK3-induced translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, thereby inhibiting IL-15/JAK3/STAT5 signaling. They further showed that chondrocyte-specific deletion of Sirt6 exacerbated OA, while pharmacological activation of Sirt6 significantly reduced chondrocyte senescence. Liu et al. 106 investigated the effects of α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), a tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolite with anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties that decrease with age. They found reduced α-KG levels in human OA cartilage and IL-1β-induced osteoarthritic chondrocytes. α-KG supplementation promoted chondrocyte proliferation, inhibited apoptosis, increased Acan and Col2a1 expression, and decreased MMP-13, ADAMTS-5, IL-6, and TNF-α expression. Mdivi-1, a mitophagy inhibitor, suppressed α-KG’s beneficial effects. Shen et al. 107 showed that toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) stimulation in human chondrocytes suppressed Col2a1 and Acan, induced MMP-3 and ADAMTS-5 expression, and increased secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including CCL -3, -4, TNFα, interferon-γ (IFNγ), IL -6, -8, and GM-CSF. Additionally, TLR2 stimulation also impaired mitochondrial function, reducing ATP production. RNA seq analysis revealed upregulation of nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2), IL -6, -8, and GM-CSF, along with downregulation of NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4), and upregulation of the antioxidant thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) and mitochondrial ROS-specific scavenger superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2). Inhibition of NOS partially restored the expression of these genes and mitochondrial function. Correspondingly, they reported that 2-year-old Nos2 − /− mice were protected from age-related OA development.

Estrogen deficiency-related transcriptomic changes in OA

Sex-specific differences in OA

Most studies on OA have been conducted predominantly on male samples, despite epidemiological data clearly showing a higher prevalence of the condition in women2,3,4,20,108. It is critically important to expand research to include both male and female subjects since OA demonstrates significant sex-based disparities in its progression and treatment outcomes. This sex disparity is evident in factors such as differences in joint biomechanics, hormonal influences, pain perception, and inflammatory responses between men and women5,21,22,26,109,110. Understanding these sex-specific variations is essential for advancing precision medicine approaches that can provide more targeted and effective treatments.

The knee and hand joints have the highest global prevalence of OA and exhibit the most significant sex differences2,111. Szilagyi et al. 112 demonstrated sex-specific differences in both the presence and relative risk of various factors, particularly body mass index, which has a stronger impact on women than men in radiographic knee. Several factors in knee joint health display sexual dimorphism including cartilage volume, bone and meniscus shape, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) size, metabolism, and sex hormones. OA has a higher prevalence in women, especially among postmenopausal women5,21. Hernandez et al. 113 reviewed sex-specific risks of knee OA before and after menopause in terms of (i) human anatomy in both healthy and pathological conditions, (ii) physical activity and response to injury, and (iii) metabolic signatures. They concluded that sex-specific anatomic, biologic, and metabolic factors early in life might help avoid the higher severity and incidence of OA in women later in life. Similarly, a recent study by Eckstein et al. 114 observed sex-specific differences in joint space width, meniscus damage, ligament size, and cartilage morphometry, with women having smaller ligament and cartilage measures. These findings suggest that female knee joints may be structurally more vulnerable and at greater risk of developing OA. Kuszel et al. 115 investigated sex-specific telomere length differences in chondrocytes and leukocytes derived from knee OA cartilage. They demonstrated that female OA patients exhibited greater telomere length reduction compared to female controls and had shorter telomeres in severely affected cartilage than male patients.

Sex-specific transcriptomic changes utilizing GEO datasets

Several publications have highlighted sex-specific transcriptomic changes in OA using GEO datasets. For instance, Wang et al. 116 analyzed GSE36700 and GSE55457 to determine key genes and pathways mediating biological differences between postmenopausal OA females and OA males. They identified seven hub genes — epidermal growth factor (EGF), Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2), cell division Cycle 42 (CDC42), phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 2 (PIK3R2), lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (LCK), casitas B-lineage lymphoma proto-oncogene (CBL), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) — which were mainly enriched in the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, osteoclast differentiation, and focal adhesion in postmenopausal females. Similarly, Li et al. 117 analyzed GSE114007 and found that extracellular matrix organization (involving genes like Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, and Sparc) plays a major role in OA cartilage of females compared to males. Pathways enriched in OA-affected female cartilage included extracellular matrix organization, collagen biosynthesis, and proteoglycans, suggesting that structural remodeling is more prominent in females with OA.

It is important to note that Malmierca-Merlo et al. 118 developed a tool called “MetaFun” (https://bioinfo.cipf.es/metafun), a web-based platform designed for meta-analyzing multiple transcriptomic datasets from a sex-based perspective. MetaFun is unique compared to other tools like MetaGenyo (for the meta-analysis of genetic association studies; https://metagenyo.genyo.es/) and ImaGEO (for integrative meta-analysis of GEO data; https://imageo.genyo.es/). For OA research, these tools enable the integration of transcriptomic data from OA patients and healthy controls to identify sex-specific transcriptomic profiles, facilitating the discovery of differentially expressed genes and pathways that contribute to the sex-based variations in OA progression.

The link between estrogen and OA

Although other factors are important in OA development, the decline in estrogen levels that occurs during menopause leads to an increased risk of developing OA21,119. Estrogen inhibits inflammation, protects chondrocytes from associated degenerative process, and delays OA21,120,121. Estrogen also promotes synthesis of proteoglycan and collagen by chondrocytes and the expression of cartilage-specific genes122,123,124. Furthermore, pro-inflammatory cytokine expression by cytokines is attenuated by hormone replacement therapy23. Hormone replacement therapy is the gold standard for treating menopausal symptoms21,125. Epidemiologic studies of estrogen and OA, specifically focusing on estrogen deficiency and hormone replacement therapy, have been reviewed elsewhere126. Clinical studies demonstrate that estrogen supplementation leads to modest but sustained reductions in joint pain frequency among postmenopausal women127. Specifically, analyses of clinical trial data reveal that the prevalence and severity of joint pain in postmenopausal patients is lower among those receiving estrogen supplementation compared to those receiving placebo, calcium, or vitamin D127,128. While there are promising results regarding hormone replacement therapy, its efficacy in managing OA remains uncertain, due to inadequate clinical reports125,129,130. The risks of hormone replacement therapy differ depending on type, dose, duration of use, route of administration, and timing of initiation131,132,133,134 Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are a specific class of estrogen receptor binding compounds that exhibit tissue-selective effects. Current studies demonstrate that SERMs have more consistent beneficial effects on bone tissue, leading to the approval of lasofoxifene and bazedoxifene for osteoporosis treatment in the USA135,136,137. Additional studies have found SERMs also beneficially impact other joint tissues, helping to maintain overall joint health138.

The link between estrogen receptors and estrogen-related receptors in OA

Estrogen receptors (ERs) play a pivotal role in the complex relationship between aging and OA, particularly given the increased prevalence of OA in postmenopausal women. Through its two primary forms — estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and estrogen receptor-β (ERβ) — these classical nuclear receptors mediate estrogen’s diverse effects on physiological processes and disease-associated pathway139,140. Studies on the estrogen-related receptors (ERRα, ERRβ, and ERRγ), a subfamily of orphan nuclear receptors closely related to ERs, reveal that ERRs share target genes, coregulatory proteins, ligands, and sites of action with ERs141,142,143. Despite their structural similarity to ERs, ERRs cannot bind endogenous estrogen or its derivatives and are thus classified as orphan nuclear receptors144. ERRs do not directly participate in classic estrogen signaling pathways but exert significant influence on estrogenic responses through various mechanisms145. They interact with estrogen signaling pathways by sharing common target genes and DNA binding sites with ERs, competing for coregulators, and modulating ER expression145,146. Through these interactions, ERRs impact key estrogen-dependent processes, including cell proliferation, survival, and energy metabolism in estrogen-responsive tissues147,148.

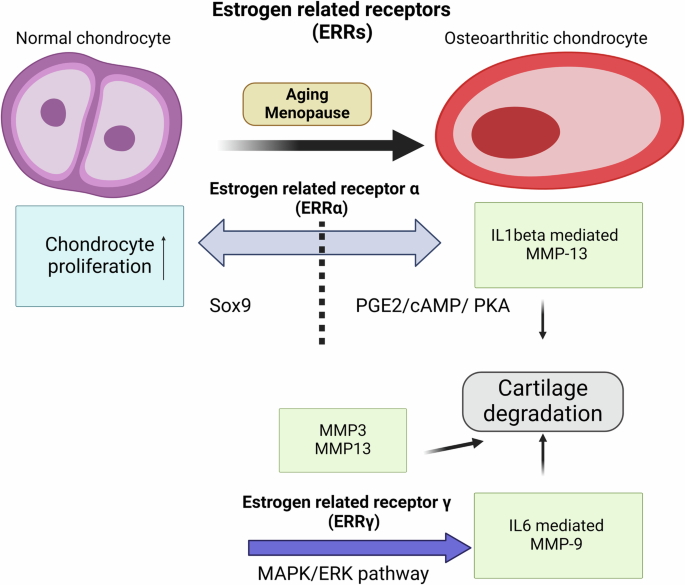

Studies suggest that mainly ERRα and ERRγ play crucial roles in protecting against OA24. Fig. 2 illustrates the intracellular signaling pathways that regulate the activity of ERRα and ERRγ in articular cartilage. Notably, ERRα has dual functions in the occurrence and development of OA. On the one hand ERRα promotes the cartilage formation by upregulating Sox-9 in cell line149 and rat mandibular condylar chondrocytes150. Kim et al. 151 demonstrated ERRα directly regulates Sox-9 expression and is required for cartilage development in zebra fish. ERRα binding elements are present in the upstream regions of Sox-9, indicating that ERRα may directly regulate Sox-9 expression by binding to these elements. On the other hand, several studies showed possible association of ERRα with OA pathogenesis. Bonnelye et al. 152 reported the involvement of ERRα in IL-1β mediated degradation of extracellular matrix. ERRα is produced in response to IL-1β stimulation through the PGE2/cAMP/ PKA signaling pathways and stimulates MMP-13 production. Bonnelye et al. 153 and Tang et al. 24 have extensively reviewed mechanisms of ERRα on cartilage and OA; however, further research is needed to fully understand the crosstalk between inflammatory signaling pathways and ERRα function in cartilage.

Aging and menopause lead to disruption of estrogen related receptors alpha (ERRα) and gamma (ERRγ) signaling. Interleukin 1 Beta (IL-1β) stimulation activates ERRα through the prostaglandin E2/cyclic adenosine monophosphate/protein kinase A (PGE2/cAMP/PKA) pathway, resulting in increased matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) production. Conversely, ERRα promotes chondrocyte proliferation via SRY-box transcription factor 9 (Sox-9) upregulation. Overexpression of ERRγ regulates interleukin 6 (IL-6) signaling and cause increased production of MMP-9, leading to molecular dysfunction, disrupted homeostasis, and subsequent cartilage degradation. Elevated levels of ERRγ lead to the upregulation of MMP-3 and MMP-13, contributing to the breakdown of cartilage matrix.

Several studies demonstrated that ERRγ has catabolic effects on cartilage homeostasis in OA pathogenesis154. For example, Cardelli et al. 155 demonstrated that ERRγ stimulates MMP-9 expression via the IL-6-mediated MAPK/ERK pathway in OA progression. Cartilage-specific ERRγ transgenic mice exhibited chondrodysplasia, characterized by repressed chondrocyte proliferation, which decreases the proliferative zone of the growth plate and results in reduced bone length. Son et al. 156 demonstrated ERRγ was specifically upregulated in chondrocytes of human osteoarthritic cartilage and various transgenic mice models of OA by upregulating MMP-3 and -13.

Studies have demonstrated that ERα serves as a critical regulator of chondrocyte phenotype in OA28,157,158. In OA patient chondrocytes, ERα expression becomes dysregulated, with this disruption occurring more frequently with advancing age159,160,161. This age-related dysregulation suggests ERα plays a fundamental role in modulating both cellular senescence and chondrocyte aging processes161. Table 2 presents a summary of key findings from studies that explore the role of estrogen in the pathogenesis of OA and its relationship with aging. Wang et al. 162 found ERα levels were lower in damaged versus preserved cartilage from OA knees. Knocking down ERα increased chondrocyte responses to mechanical loading and the expression of senescence markers like p16INK4a. Restoring ERα decreased expression of senescence markers and reversed osteoarthritic changes in chondrocytes. Zhang et al. 163 demonstrated DNA damage and senescence properties along with reduced ERα levels in OA chondrocytes. Jiang et al. 164 showed a role of estrogen in post-menopausal OA by co-culturing chondrocytes with subchondral osteoblasts from ovariectomized osteoarthritic (OVX-OA) mice led to downregulation of anabolic factors and upregulation of catabolic factors in the chondrocytes. Proteomics identified Sparc as a key hub protein. RNA seq revealed the AMP- activated protein kinase/forkhead box O 3a (AMPK/FoxO3a) pathway was downregulated in chondrocytes by factors from OVX-OA osteoblasts, promoting cartilage breakdown. Treating chondrocytes with an AMPK agonist partially reversed this. The study demonstrates how estrogen deficiency enables crosstalk between subchondral bone and cartilage to drive OA progression after menopause.

In addition to treating post-menopausal with estrogen, there is interest in using estrogen analogs derived from plants. For example, Madzuki et al. 165. demonstrated that in an OVX-OA rat model, treatment with the estrogenic herb, Labisia pumila, resulted in the downregulation of cartilage catabolic markers, including MMP-13, runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), Col10a, ERα, caspase 3 (CASP3), and hypoxia-inducible factor 2 alpha (HIF2α). Huang et al. 166 examined another estrogen plant-derived analog, psoralen, on an ACL transection induced rabbit OA model. They found that psoralen had effects similar to estrogen, promoting the expression of estrogen target genes cathepsin D (CTSD), progesterone receptor (PGR), trefoil factor 1 (TFF1), and decreasing the expression of the inflammation-related gene TNFα, IL -1β, and -6. In vivo results indicated that psoralen had chondroprotective and subchondral bone preserving effects similar to estrogen.

Animal models for pre-clinical studies of age-related OA and estrogen

Most preclinical OA studies have utilized post-traumatic injury models including; (1) DMM, (2) ACL transection, and (3) mono-iodoacetate (MIA) injection167,168,169. However, these post-traumatic models in young animals do not accurately reflect the molecular profile and pathogenesis of age-related OA that commonly occurs in older humans. Given that aging is the greatest risk factor for OA, it is unsurprising that findings from traumatic OA models in young mice have failed to translate into effective therapies for older patients170,171,172. Multiple studies have emphasized the need for appropriate preclinical models that accurately recapitulate aging-associated OA. Loeser et al. 82 used the DMM model to compare OA development and gene expression changes in young and older adult male mice. The 12-month-old mice at surgery demonstrated approximately twice the severity of OA changes in the joint compared to the 12-week-old mice. The same group173 further demonstrated progressive histological OA changes starting within two weeks after DMM surgery, worsening over 16 weeks. Their microarray results demonstrated that approximately 371 genes were differentially expressed, which OA showed three distinct phases: (i) an early stage (2-4 weeks) characterized by upregulation of morphogenesis and development-related genes, including growth factors, extracellular matrix genes, and transcription factors (Atf2, Creb3l1, and Erg); (ii) a quiescent middle stage (8 weeks) marked by downregulation of cell division and cytoskeletal genes; (iii) and a late stage (16 weeks) showing increased expression of extracellular matrix genes, particularly arginine-rich end leucine-rich repeat protein (Prelp), collagen type III alpha 1 chain (Col3a1), and FMOD, which were confirmed by immunostaining in cartilage and osteophytes. These findings suggest that OA develops in phases, with initial matrix remodeling followed by a temporary quieting of activity, potentially due to joint stabilization by mature osteophytes. Lijima et al. 174 meta-analysis demonstrated most mouse OA studies use surgical models in young mice, which does not reflect age-related OA in humans. There is only 3% gene expression overlap between surgical OA models in young mice versus OA developing naturally with age. In their subsequent study84 they characterized OA progression across lifespan and sex in mice. Interestingly, they found aged female mice maintained better cartilage integrity than males, conflicting with human sex differences in OA severity. They suggest this may be because the aged female mice were non-menopausal, as evidenced by stable estrogen levels over time. This study revealed an important limitation concerning the use of mice for studying the effects of menopause on disease, namely that rodents continue estrogen production into old age, preventing modeling of menopausal effects on OA progression. While mice can mimic certain aging-related cartilage changes, they cannot be used to study interactions between reproductive senescence and OA pathogenesis. Gilmer et al. 133 conducted a systematic review to summarize the current literature on animal models of menopause and OA and investigate the impact of estrogen treatment timing and dosage on cartilage degeneration. They found that post-menopausal animals, mostly induced via ovariectomy, displayed worse cartilage outcomes compared to non-menopausal controls. Additional mathematical modeling suggested potential chondroprotective effects of earlier and higher-dose estrogen treatment after menopause. These studies highlight the need for improved animal models that consider age-related changes and natural menopause.

Conclusion

This review article highlights the intricate interplay between aging, estrogen, and transcriptomic changes in OA development. Aging and estrogen deficiency promote OA development by inducing chondrocyte senescence, inflammation, and extracellular matrix degradation. Comparisons of OA cartilage to healthy cartilage from age-matched controls without OA are lacking, limiting understanding of how aging alone impacts primary OA onset and progression. Transcriptomic analyses have uncovered some age-associated gene expression changes in osteoarthritic cartilage, such as upregulation of pro-inflammatory genes (IL -1β, -6, -7, -8, -17, -33); chemokines (Ccl- 2, -3, -4, -5, -8; Cxcl – 5, -9, -13); genes for matrix degradation enzymes (MMP -1, -2, -3, -9 -10, -13, -14, -19, ADAMTS -4, -5, -8, and -12); and downregulation of extracellular matrix gene expressions (Col2a1, Col9a1/2/3, Col11a2, matrillin 3, Acan, and Hapln1). The identification of key transcription factors (AHR, Atf2, Creb3l1, E2F1, EGR1, EID1, EID2, Erg, FOSL1, FOSL2, FOXM1, HIF1α, HSP90AA1, JUN, JUND, KLF4, MYC, NBR1, NCOA3, RUNX2, SOX -6, -9, SP100, TIMP2, and ZEB1) offers insight into the regulatory networks driving age-related cartilage degeneration in OA.

Transcriptomic analyses have uncovered distinct sex-specific molecular signatures in OA, identifying crucial hub genes and pathways that differ between male and female patients. Seven key hub genes (CBL, CDC42, EGF, ERBB2, LCK, PIK3R2, and STAT1) were identified in postmenopausal females with OA. These genes are enriched in pathways related to PI3K-Akt signaling, osteoclast differentiation, focal adhesion, and immune response. The complex interplay between estrogen, ERs, and ERRs emerges as a central mechanism in OA development. ERα serves as a critical regulator of chondrocyte phenotype, with its age-related dysregulation contributing to cellular senescence and cartilage degradation. The dual nature of ERRα in both promoting cartilage formation through Sox-9 regulation while also contributing to inflammatory responses that drive MMP-13 expression highlights the complexity of estrogen signaling in joint homeostasis. ERRγ plays a significant role in OA pathogenesis by driving catabolic processes in cartilage, including the upregulation of MMP-9 through the IL-6-mediated MAPK/ERK pathway and the production of MMP-3 and -13, contributing to chondrocyte dysfunction and cartilage degradation in both human and animal models. More research is required to fully elucidate the molecular connections between estrogen, ERs, ERRs, and OA pathogenesis.

Current preclinical OA models face significant limitations in translating findings to human age-related OA. The predominant use of post-traumatic injury models in young animals fails to capture the complex molecular characteristics of age-related OA in humans. Studies emphasize the importance of developing preclinical models that capture the complexity of aging-associated OA. The continuous estrogen production in aged female mice presents a particular challenge for studying menopause-related OA pathogenesis. While ovariectomy models offer insights into estrogen’s role in cartilage protection, they cannot fully replicate the natural progression of menopause-associated OA. Improved animal models considering age-related changes and natural menopause are needed to advance our understanding of OA pathogenesis.

Responses