The need for holistic approaches to climate-smart rice production

Methane is the key issue for eco-friendly rice production

Rice is the staple food of half the world’s population, providing 21% of the dietary energy supply while using 11% of global cropland1. Rice production has continued to rise since the beginning of the Green Revolution in the late 1960s due to the introduction of high-yielding varieties, extensive use of agricultural inputs, investments in irrigation infrastructure, extension education programs, and subsidies2. Due to both population growth and economic expansion in developing nations, it is expected that the world’s rice consumption will rise from 480 million tons (Mt) of milled rice in 2014 to around 550 Mt by 20302. However, rice has the highest area-scaled (per unit land area) and yield-scaled (per unit yield) greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions among all food crops, contributing 2.5% to anthropogenic global warming as it releases GHGs, mainly methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), which account for 22% and 11% of agricultural emissions, respectively1.

Rice is the only crop grown under continuous flooding conditions that contribute to the formation of an anoxic environment leading to the production and emission of CH4, while nitrogen fertilization (in the form of urea) is the main contributor to N2O emissions from paddy soils. The trajectory of anthropogenic CH4 emissions is currently one of the two most intensive warming scenarios3. Therefore, reducing anthropogenic CH4 emissions is not only a viable option for rapid mitigation of climate change, but also essential to meet the 1.5 °C target of the Paris Agreement. The Global Methane Pledge, which was signed by more than 100 nations at COP26 in Glasgow, intends to cut CH4 emissions by 30% below 2020 levels by 20303.

Potential methods and constraints for mitigating CH4 emissions

Over the past two decades, much of the research has focused on identifying agricultural management practices that reduce GHG emissions from rice production while ensuring high yields. In the recent review, Qian et al.1, summarized the potential agricultural management strategies to mitigate GHG emissions while ensuring yield sustainability. These are: (i) water management, which includes single and multiple drainage [alternate wetting and drying (AWD)], maintaining soil water potential at –10 to –20 kPa and water table below soil surface (10–25 cm), drainage during high CH4 emission phase and maintaining non-flooded soil conditions during fallow (non-cropping) period, (ii) organic matter management, which includes the addition of compost and straw in the fallow period and the addition of green manure with low C:N ratio to low soil organic carbon (SOC) soils and the removal or return of straw in the fallow period to high SOC soils, (iii) mineral N management, such as optimal N application rate at which maximum yield is achieved, sub-surface (below 10 cm soil depth) N application, and application of enhanced efficiency N fertilizers or ammonium sulfate, (iv) tillage and crop establishment such as no tillage in rice cropping season if transplanting equipment and technology are available, conventional tillage during the fallow season, and direct seeding if direct-seeding equipment and technology are available, (v) lime application on acidic (pH < 5.5) soils, and (vi) the selection of rice cultivars based on local high yielding and low GHG emitting cultivars (Table 1).

Optimizing a single agricultural practice has limited potential to reduce GHG emissions and improve rice yields, and it is highly dependent on local conditions. The benefits of reducing GHG emissions are often offset by the reduction in yields4. Although the non-continuous flooding (NCF) method has great potential to reduce CH4 emissions from rice fields, there are several constraints, such as the fact that it is impossible to drain the water in the low-lying rice fields of South Asia, and farmers in the rainfed production system do not even drain the water from the midland fields because of the uncertainty of rain. This limits the adaptation of the NCF method in the following ways1,4: (i) it can only be used in paddy fields with well-prepared irrigation and drainage systems; (ii) it is difficult to control the water in the paddy soils, especially during the rainy season, (iii) it is not appealing to farmers who must pay a fixed irrigation fee each season; and (iv) an inappropriate NCF method, such as drainage over a long period of time at an inappropriate growth stage of rice, may result in a decrease in rice production. Straw removal could be an effective strategy to reduce GHG emissions. However, repeated removal of straw can have a very negative impact on soil fertility in the long-term by decreasing soil organic matter (SOM). Moreover, this results in net CO2 emissions to the atmosphere and reduces the potential for carbon sequestration in the soil4. Likewise, the high cost, unavailability of material resources, and the absence of efficient and non-polluting equipment for producing biochar limit the adaptation of biochar in the rice farming system1. In comparison to transplanted flooding rice cultivation, dry direct seeding and rotation with upland crops may lower soil fertility if they have longer aerobic soil periods4. The toxicity of hydrogen sulfide, which is formed in the soil under anaerobic conditions when sulfate-containing fertilizer is applied, can reduce rice yield4. Therefore, smart agronomic management practices based on cultivar selection, water management, organic amendment, nitrogen fertilization and tillage should be optimized to reduce GHG emissions without jeopardizing food security. Smart agronomic management practices and constraints for sustainable rice production are outlined in Table 1.

Climate-smart rice production: the need of the hour

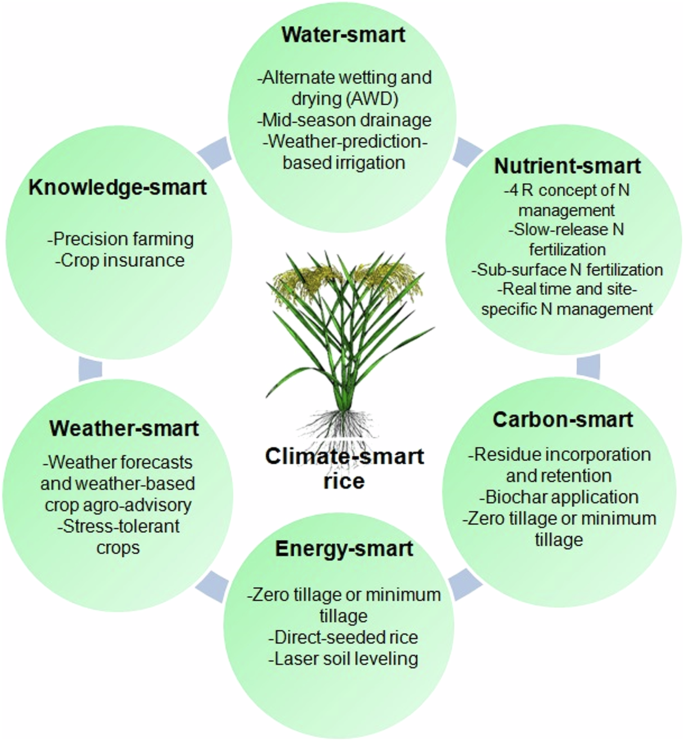

Climate-smart agriculture is an integrated approach that has recently been promoted as a way to increase agricultural productivity and incomes, adapt to and build resilience to climate change, and reduce GHG emissions5. The key dimensions to produce climate-smart rice (CSR) include water-smart (e.g., AWD and weather-prediction-based irrigation), nutrient-smart (e.g., 4R concept such as right time, right rate, right source, and right place of the fertilizers and manure application based on local agro- environment conditions; slow-release nitrogen fertilizer application; sub-surface nitrogen fertilizer application; and real-time and site-specific nutrient management), carbon-smart (e.g., residue incorporation and retention, biochar application, and zero tillage or minimum tillage), energy-smart (e.g., zero tillage or minimum tillage, direct-seeded rice, and laser soil levelling), weather-smart (e.g., weather forecasts and weather-based crop agro-advisory, stress-tolerant crops), and knowledge-smart (e.g., precision farming and crop insurance) technologies (Fig. 1). Considering these key dimensions to produce CSR has shown great promise, albeit there are also some trade-offs. For example, AWD may reduce the amount of water used in fields, but this may lead to a greater need for agrochemicals, or herbicides, to combat a potential increase in weed infestation4. It might also result in increased N2O emissions4. The selection of appropriate CSR production strategies to improve yields and soil health while reducing environmental pollution therefore requires consideration of local environmental factors such as climate and soil conditions and their interaction with other management practices. For instance, no-till with residue retention demonstrated a marked yield advantage, increased water use efficiency, net economic return, increased SOC sequestration, and reduced global warming potential in rice-wheat systems than rice-rice and rice-maize systems6. It has been shown that combining no-till with residue retention and crop rotation minimizes the negative impacts of no-till and increases rain-fed rice productivity in dry climates, suggesting that it can be an important strategy for adapting to climate change in regions that are becoming increasingly drier6. Optimizing field management practices to adapt and mitigate climate change could balance and promote trade-offs between GHG emissions, soil carbon sequestration, and rice production, and combining the advantages of individual management practices into a systematic field operation could increase efficiency. Research that takes into account the interdependencies between various components of rice production systems and involves stakeholders in the decision-making process is necessary to uncover trade-offs between field management methods and balance competing objectives.

The key dimensions to produce climate-smart rice (CSR).

Despite the promise of CSR production to improve food security, especially in South Asia, most CSR practices and technologies have not been widely adopted. For example, while some technologies and practices—like crop diversification and green manure—have been around for a while, many others—like zero tillage and AWD methods—are still having trouble gaining traction despite their shown benefits. Key strategies to overcome the barriers to CSR adoption include2,7 (1) raising farmers’ awareness of CSR cultivation through peer-to-peer networks and training programs in rural communities, (2) providing farmers with timely and reliable weather forecasts and climate data, (3) offering crop insurance to make CSR production more affordable for smallholder farmers, (4) rural infrastructure should be developed to facilitate crop and income diversification, (5) rice stock management and trade must be managed to balance market supply, and (6) monitoring and evaluation of CSR adoption over time is necessary to determine whether farmers continue to adopt CSR practices and technologies and, if not, what challenges farmers encounter. To adopt climate-resilient varieties and practices that are in line with the United Nations Green Growth Goals, governments should promote capacity building and integrate the latest research and development findings into their rice sector strategy. Equally important are policy reforms that promote diversification of rural incomes, improve trade flows, and effectively manage production and marketing risks.

Enhancing water productivity in rice systems

Rice cultivation has a significant water need. It uses more than half of the irrigation water available to the agricultural sector and accounts for 24–30% of global freshwater withdrawal8. Water used to produce 1 kg of rice ranges from 800 to 5000 L, with an average of 2500 L8. Since rice farming uses most of the freshwater available, it is likely to be most negatively affected by climate change due to water stress. A key aspect of helping rice farmers cope with water scarcity is to develop novel “water-saving technologies” and improve ‘water productivity’ (production in terms of yields, nutrition, income, or both per unit water use)8,9.

Numerous water-saving innovations that were created through field testing in various agroecologies have demonstrated encouraging outcomes in some situations and, if scaled up, might save a substantial quantity of irrigation water. The water-saving technologies are primarily based on prudent management of (i) irrigation scheduling (e.g., AWD, tensiometer-based irrigation management, and saturated soil culture), (ii) improved irrigation methods (e.g., surface irrigation, check basins, border strip irrigation, and drip irrigation), (iii) water-efficient rice production systems (e.g., direct-seeded rice, aerobic rice, and system of rice intensification), and (iv) agronomic practices for higher water-use efficiency (e.g., laser land leveling, and sunken and raised bed)8,9,10. Each approach has pros and cons of its own, which are listed in Table 2. The adoption of water-saving practices and technologies varies from region to region and is influenced by soil type, climate, resource availability, and skill level. In areas where water is scarce, it is essential to develop and implement targeted initiatives that provide attractive incentives to encourage the adoption of water-saving practices and technologies. A concerted effort by all stakeholders, including farmers, extension organizations, and the government, is needed to encourage and facilitate the widespread adoption of these technologies. Other research priorities include the identification of rice varieties for tolerance to water stress through conventional breeding, and the selection of rice varieties through molecular markers, and the use of advanced molecular/biotechnological tools for water-limited conditions. By integrating appropriate nutrient management strategies, optimal irrigation management strategies, and drought-tolerant varieties with low water requirements will not only conserve water but also promote sustainable rice production by increasing water productivity, reducing environmental impacts, and improving grain yield8,9.

Co-culture of rice and aquatic animals for sustainable intensification

Rice and aquatic animals such as fish, prawns, crabs, shrimps, turtles, and frogs are the favored foods that are essential for a healthy and nutritious diet and form the basis of local and national economies in Asia11. While most of the changes in agriculture and aquaculture in recent decades have been based on the intensification of monocultures to increase rice and fish yields, agroecological practices that promote biodiversity and utilize natural processes are particularly important to achieve a shift towards more ecological, inclusive, and nutritionally sensitive food systems. Rice and animal co-culture (RAC) is often integrated into the same temporal, spatial, and social domains, but the nature and scale of production practices are highly heterogeneous. In Cambodia, the majority (~80%) of rice land is used for rice-fish co-culture, which relies largely on natural processes, while in Vietnam, rice-shrimp co-culture is increasingly dependent on inputs and infrastructure12. A growing body of research has shown that RAC can improve food and nutrition security, diversify rural livelihoods and improve incomes, and conserve biodiversity while reducing the environmental footprint of rice production11,12. Nevertheless, RAC has spread unevenly, and campaigns to promote the practice have generally failed12. This may be due to a number of factors, including improper and inadequate extension programs, improperly selected or ineffective pesticides, and a lack of financial resources. Developing a typology of integrated production practices that illustrates the nature and extent of aquatic species stocking, water management, use of synthetic inputs, and institutions that control access to aquatic species, as well as incorporating research and innovations that have improved the performance of each type of practice, can bring success to RAC12. The future research on RAC systems should focus on improving biodiversity (i.e., preserving indigenous species, avoiding species invasions), resource management (i.e., life cycle assessment, nutrient footprint, and carbon neutrality), and quantifying the contributions of RAC systems to Sustainable Development Goals at the target and indicator levels.

Breeding rice for climate resilience, high yield and low CH4

Climate change is anticipated to have drastic effects on rice yields mainly due to increased temperatures and water scarcity2. Unlike other crops, rice contributes significantly to anthropogenic GHG emissions and global warming because it releases GHGs, primarily CH4, from rice fields1. The impact of climate change on rice production can therefore be dealt with in two ways: breeding climate-resilient rice and modifying agronomic management strategies as well as breeding rice for low CH4 emissions without scarifying yield.

Breeding efforts over the past few decades have focused on developing high-yielding rice varieties that can grow better under persistent flooding conditions, in which seedlings are generally grown in nurseries and then transplanted into flooded soils. In view of climate change, shifting rice cultivation that require less water (e.g., AWD and direct-seeded rice) presents new challenges, that must be addressed in rice breeding. These challenges include seedling establishment (characterized by traits like rapid uniform germination even under anaerobic conditions, and early vigor), adaptation to aerobic soil conditions (characterized by traits like moderate drought tolerance, and water and nutrient uptake efficiency), and reaching maturity (characterized by traits like lodging resistance, and weed, nematode, and herbicide resistance)13. In the last two decades, a significant effort has been made to develop climate-resilient rice varieties. A number of QTL (quantitative trait loci) associated with abiotic stress tolerance traits such as seed germination and seedling vigor (e.g., qVI-1, qSSD-2, qSFW-2, qRSA-2, qRV-2, qRFW-2, qSH-3, qSFW-3, qGI-7, qVI-7, qSFW-7, qSFW-8, and qRV-8)14, early vigor (e.g., qEV3.2, qEV4.1, qEV5.1, qEV5.2, and qEV6.1)15 nitrogen use efficiency (e.g., qNUE2.1, qNUE4.1, qNUE6.1, qNUE6.2, qNUE10.1, and qNUE10.2)16, grain yield and water use efficiency (e.g., qDTY12.1)17, drought tolerance (e.g., qDT2.4, qDT2.8, qDT2.9, qDT6.5, qDT7.1, qDT10.3, and qDT11.5)18, stomatal conductance and leaf photosynthesis (e.g., qCTd11)19, lodging resistance (e.g., qLR1 and qLR8)20, and nematode resistance (e.g., qMGR4.1, qMGR7.1, qMGR9.1, qGR4.1, and qGR8.1)21 were identified. QTL mapping and trait development activities help identify the genomic regions of interest that can be transferred by marker-assisted breeding for the development of climate-resilient rice varieties13. Recent developments in genomics, high-throughput phenomics, and breeding technologies, and state-of-the-art genome editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 and vector-based RNA delivery, combined with artificial intelligence, have opened new avenues for the rapid improvement of climate-resilient rice varieties.

Currently, efforts to reduce CH4 emissions from rice fields are largely focused on agricultural practices that can be difficult to implement effectively. Aside from farming practices, genetic modulation of photosynthetic allocation can also reduce CH4 emissions. For instance, by allocating more photosynthates to aboveground biomass (increasing starch content in seeds and stems) than to roots, the rice cultivar SUSIBA2, which carries a transcription factor for sugar signaling in barley, lowers CH4 emissions1. In this context, spikelet removal is reported to significantly increase CH4 emissions1. A recent study found that the loss-of-function rice allele gs3 reduces CH4 emissions by allocating more photosynthates to grain and less to root, and boosts yields by increasing grain size and weight22. While it is crucial to develop new rice varieties with lower CH4 emissions, there is currently a dearth of research on the use of breeding techniques to benefit from natural variation in rice. Rice cultivars with the following characteristics have been shown to have lower CH4 emissions without yield loss1,23: (i) high root oxidizing potential; (ii) increased root porosity; (iii) reduced root permeability; (iv) enlarged aerenchyma channels, (v) smaller number of unproductive tillers; (vi) effective tillers with few aerenchyma; (vii) increased rhizosphere and reduced carbon release from root zone; (viii) high harvest index; (ix) short life cycle; (x) increased water use efficiency; and (xi) increased nitrogen use efficiency. Therefore, rice genotypes that have been phenotyped according to these relevant criteria can be used as donors in breeding programs. Identification of QTL and candidate genes linked to CH4 emission and plant traits that mitigate CH4 emissions, as well as association mapping to identify genomic segments underlying the particular region associated with low CH4 emission or associated traits, can be used to develop a rice variety with low CH4 emission and high yield. Despite the paucity of genomic data on low CH4 emitting rice varieties, it is possible to compare, analyze, and explore genetic and allelic differences between high and low CH4 emission rice lines. CSR production is now possible thanks to recent developments in next-generation sequencing, multi-omics, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Conclusion

Recognizing that the paradigm of CSR production must balance productivity and environmental sustainability, CSR production practices have considered the potential of rice production to reduce GHG emissions, particularly CH4, and sequester carbon while ensuring food security for small and marginal farmers. CSR production requires multi-pronged tactics, right from choosing the right seed or cultivar, irrigation management, integrated nitrogen management, residue return and removal, and post-harvest practices. Weather-based crop agro-advisory, knowledge-based precision farming, and state-of-the-art plant breeding can increase the efficiency of CSR production practices. However, strong commitment from policymakers and other stakeholders is needed to fully realize the benefits of CSR production and achieve widespread adoption. Conducting regular outreach programs to disseminate information on various technological advances can ensure that farmers gain access to technologies to produce CSR.

Responses