The oral-gut microbiota axis: a link in cardiometabolic diseases

Introduction

The human body hosts trillions of microorganisms that inhabit various ecological niches such as the gut, mouth, and skin, forming a symbiotic relationship crucial for maintaining health1. Among these habitats, the intestinal tract harbors the highest density of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, and archaea. This microbiota plays significant roles in digestion, absorption, immune system development, and metabolic regulation2,3. Due to its extensive functions, the intestinal microecology has garnered increasing attention4. Similarly, the oral microecology is essential for maintaining oral health and physiology5. There is significant connection between the oral and intestinal microecologies. The oral cavity is considered an endogenous reservoir for intestinal microorganisms6,7, and the translocation of oral bacteria to the intestinal may negatively impact health8. Cardiometabolic diseases, which refer to cardiovascular diseases driven by metabolic risk factors, have become a major health concern globally9,10.

Recent research has highlighted the crucial role of microecology in human health. In particular, the oral-gut microbiota axis, have important implications for cardiometabolic health. This review examines how the oral-gut microbiota axis influences cardiometabolic health, offering valuable insights for future research and clinical practice.

Microbial distribution in the oral cavity and intestinal tract

In the oral cavity, the core microbiome primarily comprises the phyla Actinomycetota, Bacteroidota, Bacillota, Fusobacteriota, Pseudomonadota, Saccharibacteria and Spirochaetota11. Actinomycetota mainly consists of the genera Corynebacterium, Rothia, and Actinomyces. Bacteroidota include Prevotella and Capnocytophaga. Fusobacteria mainly include Fusobacterium12,13. Bacillota mainly include the family Veillonellaceae, the genus Streptococcus and Granulicatella, while Pseudomonadota includes Neisseria and Haemophilus.

The gut microbiota is dominated by Bacillota, Bacteroidota, Actinomycetota, Fusobacteriota, Pseudomonadota, Verrucomicrobiota, and Cyanobacteriota14. Among these, Bacteroidota and Bacillota account for over 90%. Bacillota encompasses key genera such as Lactobacillus, Bacillus, and Clostridium15, while Bacteroidota comprise significant genera like Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, Prevotella, and Porphyromonas16 (Fig. 1).

This figure shows the predominant phyla and genera of microbiota found in the oral cavity and gut. Created with BioRender.com.

The Human Microbiome Project showed that approximately 45% of participants had overlapping oral and gut microbiota17, with more than half of the shared species belonging to the phylum Firmicutes, class Clostridia, and order Clostridiales18. This overlap suggests a complex interaction between oral and intestinal microecology, where oral bacteria can colonize the gut, significantly influencing various pathophysiological processes.

Pathways underlying the oral-gut microbiota axis

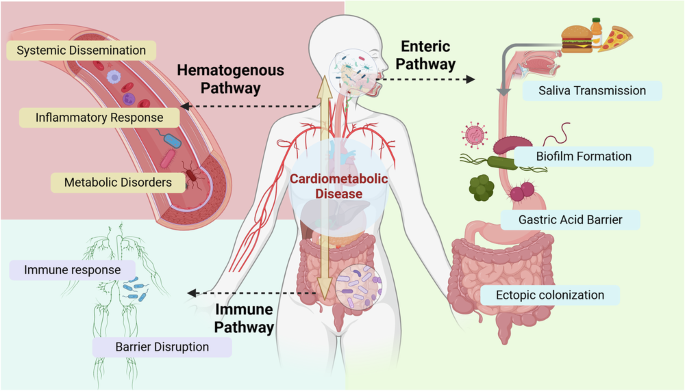

The oral cavity and intestinal tract are integral components of the digestive system, hosting distinct but interconnected microbiota. The interactions between oral and gut microbiota occur through multiple pathways, including the enteric, hematogenous, and immune pathways, each playing a critical role in modulating the oral-gut microbiota axis (see Fig. 2).

This figure illustrates the three main pathways through which oral and gut microbiota interact: the Enteric Pathway, Hematogenous Pathway, and Immune Pathway. Microbial interactions can exacerbate effects on cardiometabolic diseases through various factors, including inflammatory response, immune response and other elements. Created with BioRender.com.

Enteric pathway

The enteric pathway involves the direct transmission of oral bacteria to the gut through the digestive tract. During eating and swallowing, oral bacteria and their metabolites are carried with saliva from the mouth into the gastrointestinal tract19. Saliva plays a crucial role in the lubrication and digestion of food, as well as in the transportation of microorganisms20. The average human produces approximately 1 to 1.5 liters of saliva per day, containing around 1.5 × 1012 bacteria8. This process allows oral bacteria to potentially impact the gut microbiota.

In healthy individuals, the transmission of microbiota from the oral cavity to the gut is typically limited due to various defense mechanisms21. Gastric acid and the mucus layer, along with intestinal epithelial cells, form physical and chemical barriers that prevent colonization by oral bacteria22,23. However, certain periodontal pathogens, including Porphyromonas gingivalis, Klebsiella, Helicobacter pylori, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Parvimonas micra, and Fusobacterium nucleatum can endure harsh acidic environments and migrate to the intestine24, particularly in individuals with reduced gastric acid levels, such as those using proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)25. Moreover, Helicobacter pylori infection can disrupt oral microbiota homeostasis and further compromise the gastric environment, facilitating the enrichment of oral bacteria, including Fusobacterium nucleatum and Porphyromonas gingivalis, in the gut26.

Although gastric acid acts as a major barrier to prevent bacterial survival, certain bacteria can adhere to the surface of saliva in the form of biofilms, enabling them to bypass acidic conditions27. Biofilm formation allows pathogens such as Streptococcus mutans to persist within the oral environment by employing mechanisms like the production of reutericyclin, which inhibits neighboring commensal bacteria and promotes dysbiosis28. Cross-feeding and nutrient sharing among bacteria, including early colonizers like Fusobacterium nucleatum, facilitate biofilm development and support the survival and spread of more pathogenic bacteria like Porphyromonas gingivalis29. Moreover, bacterial communication often occurs when they are in close proximity30. Through chemical signaling, bacteria respond to the chemical, physical, and ecological characteristics of their environment. The physical and metabolic interactions between Candida albicans and Streptococcus mutans, for instance, enhance the biofilm’s structural integrity and acidogenic virulence31. Thereby promoting the ectopic colonization and survival of pathogenic bacteria.

Studies have shown that the periodontitis-related salivary microbiota can induce gut dysbiosis32. There are two explanations for the increased relative abundance of oral bacteria in feces: one is that oral bacteria invade and expand within the gut ecosystem (the Expansion hypothesis), the other is that the relative increase in oral bacteria and signify the depletion of other gut bacteria (the Marker hypothesis)33. Evidence supporting the Expansion Hypothesis comes from studies on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, where an increased abundance of Campylobacter concisus and Fusobacterium nucleatum was observed in fecal samples and intestinal biopsies. This suggests that these oral bacteria can migrate to the gut and lead to dysbiosis34. Conversely, support for the Marker Hypothesis suggests that disease associations may result from the loss of native gut commensals rather than a substantial rise in oral bacteria numbers, granting these oral taxa pathogenic potential in the gut environment33.

Additionally, gut microbiota can also influence the oral microbiota through fecal-oral transmission, either through direct contact or indirectly via contaminated food and liquids. Hands have been identified as critical vectors for the transfer of fecal and oral microorganisms within households and between individuals35.

Hematogenous pathway

The hematogenous pathway involves the systemic transmission of bacteria through the bloodstream36. Microorganisms originating in the oral cavity can enter systemic circulation due to mechanical perturbations from daily activities such as brushing or chewing, ultimately reaching distant body sites and influencing their local microbiomes37.

By traveling through the bloodstream, these microbes and their products can increase systemic inflammation, thereby contributing to a range of functional disorders38. Oral-gut pathogens can weaken mucosal barrier integrity, enabling bacteria and their byproducts to translocate into the bloodstream and disseminate to distant organs. This process may induce a systemic pro-inflammatory state triggered by TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-639. For instance, Fusobacterium nucleatum-induced apical periodontitis altered the bacterial flora in the rat gut, heart, liver, and kidney, and promoted intestinal inflammation40. Notably, the hematogenous pathway appears to be the preferred route for oral Fusobacterium nucleatum to reach colon tumors41.

Virulence factors from periodontal pathogens further exacerbate this cycle by disrupting the intestinal epithelial barrier, allowing bacteria and metabolites from the intestinal lumen to leak into the bloodstream, thus enhancing interconnections among microbial niches throughout the body42. As Porphyromonas gingivalis enters the gut, it exacerbates gut permeability and endotoxemia, which ultimately results in metabolic dysregulation and systemic inflammatory responses43. Porphyromonas gingivalis can significantly elevate endotoxemia levels by enhancing LPS in the bloodstream, which subsequently upregulates FMO3 expression, raises plasma TMAO levels, and causes gut dysbiosis and inflammation44. It also decreases the expression of tight junction proteins such as ZO-1, occludin, and Tjp1 in the small intestine, increasing gut permeability43. Additionally, studies have shown that direct injection of Pg-LPS (derived from Porphyromonas gingivalis) can induce gut microbiota changes through hematogenous transmission45. Notably, Porphyromonas gingivalis is the most abundant species detected in the coronary and femoral arteries46.

The hematogenous pathway facilitates microbial interactions within the oral-gut microbiota axis, directly contributing to the development and progression of various cardiometabolic diseases.

Immune pathway

Pathogenic microorganisms can also influence the oral-gut microbiota axis through immune pathways. Dysbiosis of the oral microbiota can interact with gut-associated immune cells, triggering immune responses that affect both oral and gut health. Oral bacteria, particularly those implicated in periodontitis, stimulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which further drive the growth of pathogenic oral bacteria and contribute to gut inflammation8,47. When oral pathogens such as Klebsiella and Enterobacter colonize the gut, they activate the inflammasome and initiate inflammation in colonic mononuclear phagocytes, leading to disturbances in the intestinal immune environment48. Klebsiella are also capable of adapting to distant mucosal environments, such as the gut, through the use of complex virulence mechanisms49. Additionally, Streptococcus gordonii has been shown to aid Candida albicans in escaping macrophages, exacerbating immune dysregulation50.

Oral dysbiosis can reduce Th17 cell levels and fecal IgA, alter the M1/M2 macrophage ratio, and lead to chronic inflammation. It also causes metabolic disturbances, such as elevated lactate and reduced succinate and n-butyrate levels, aggravating gut microbiota imbalances42. Intestinal epithelial cells play an important role in responding to invading microbes by regulating the mucosal barrier and signaling immune cells in the lamina propria to adapt to environmental changes51. Oral bacteria that ectopically colonize the gut influence lamina propria macrophages by hyperactivating the inflammasome and increasing IL-1β production, resulting in localized mucosal damage47. The ectopic colonization of oral pathogenic bacteria may disrupt the intestinal epithelial barrier, increase the secretion of inflammatory factors, disrupt the host immune system, and cause imbalances in the gut flora52. The periodontitis salivary microbiota can induce dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, exacerbating colitis by damaging the mucosal barrier53. Approximately 30% of patients with IBD present oral manifestations that may precede gastrointestinal symptoms. This suggests that systemic inflammation related to IBD can lead to changes in oral microbiota, exacerbating oral inflammation54.

Over three decades ago, John Bienenstock proposed the concept of a “common mucosal immune system”, suggesting that the mucosal immune system itself is an “organ” where mucosal immune cells distributed throughout the body can interact across different mucosal tissues and organs55. Recent evidence confirms that potentially pathogenic oral bacteria and immune cells can migrate to the gastrointestinal tract, contributing to intestinal inflammation56. Some oral bacteria can survive within immune cells, such as dendritic cells and macrophages, potentially using these cells as “vehicles” to move from the oral mucosa to the gut47. Conversely, gut pathogens can influence oral health by inducing systemic immune responses57. Radiation-induced intestinal mucosal barrier damage, characterized by a reduced proportion of CD8+ T cell and an increased proportion CD4+ T cells, can lead to changes in the oral microbiota58. The migration of intestinal Th17 cells is a key pathogenetic mechanism that promotes periodontitis, and such migration may be induced by the ectopic colonization of Porphyromonas gingivalis in the intestines59.

Mechanisms for oral microbes to thrive in the gut

Oral microbes can thrive in the gut despite the different environment by adapting to the gut’s conditions and leveraging various mechanisms. (1) Acid Tolerance: Certain oral bacteria display notable acid tolerance, allowing them to endure gastric acidity and subsequently colonize the gut24. (2) Metabolic Adaptation: Some oral microbes adapt their metabolism to the gut environment by utilizing available nutrients. Nitrate respiration promotes Veillonella parvula’s growth on organic acids and expands its metabolic capabilities, facilitating its colonization in the gut60. (3) Immune Evasion: Specific oral microbes can evade host immune responses and modulate the host immune system to create a more favorable environment for their survival and colonization in the gut61,62. (4) Interaction with Gut Microbiota: Certain oral bacteria can enhance their own survival and growth by interacting with the existing gut microbiota33.

Implications of the oral-gut microbiota axis for cardiometabolic diseases

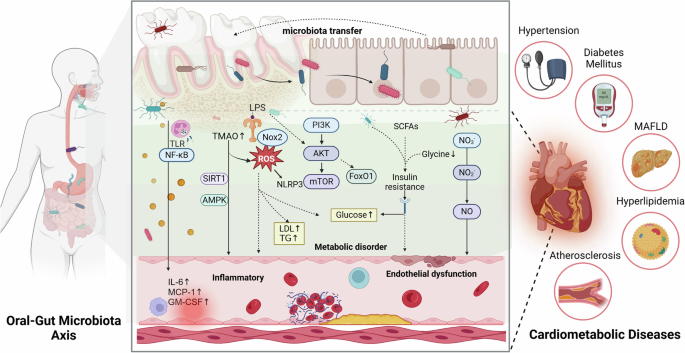

The microecology of the oral cavity and gut is intricately linked to cardiometabolic health. Emerging evidence suggests that interactions within the oral-gut microbiota axis significantly influences the development and progression of cardiometabolic diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, and so on63. Table 1 summarizes the characteristic alterations in oral and gut microbiota under disease conditions, and Fig. 3 illustrates the underlying mechanisms through which the oral-gut microbiota axis influences metabolic cardiovascular diseases.

This figure illustrates the interaction between oral and gut microbiota and their impact on cardiometabolic diseases. The translocation of bacteria between the oral cavity and gut can lead to microbial imbalances. These microbes and their metabolites can affect pathways such as TLR/NF-κB, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and the Nitrate-Nitrite-Nitric Oxide pathway, triggering systemic inflammation, metabolic disorders, and endothelial dysfunction. These processes negatively affect cardiometabolic health, contributing to conditions like hypertension, diabetes mellitus, Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD), hyperlipidemia, and atherosclerosis. This highlights the significant role of oral-gut microbiota interactions in the progression of cardiometabolic diseases. Created with BioRender.com.

Hypertension

Hypertension not only impairs vascular function but also causes target organ damage, including the heart, kidneys, and blood vessels, thereby linking it to broader cardiometabolic dysfunction64,65. Its development is often accompanied by metabolic abnormalities, such as insulin resistance and dyslipidemia66.

Hypertension is also influenced by the oral-gut microbiota axis. Certain oral bacteria are potent inducers of pro-inflammatory cytokines and have been significantly linked to the onset of hypertension67. Porphyromonas gingivalis activates vascular endothelial cells to secrete angiotensin II and pro-inflammatory cytokines, amplifying vascular inflammation and arterial hypertension68. Prevotella and Veillonella impair NO homeostasis, while Rothia and Neisseria support vascular function and blood pressure regulation through the nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway69. The presence of antibodies against specific oral bacteria, such as Campylobacter rectus, Veillonella parvula, and Prevotella melaninogenica, has been associated with increased blood pressure, suggesting an immune-mediated mechanism in hypertension70.

In hypertensive patients, increased similarity between the oral and gut microbiota has been observed, suggesting possible microbial translocation and colonization71. The ectopic colonization of the gut by salivary-derived Veillonella may exacerbate hypertension, indicating a direct link between oral and gut microbiota in hypertensive conditions72. Pre-hypertensive and hypertensive patients exhibit lower genetic richness and alpha diversity in the gut microbiome, along with a higher proportion of bacteria from the genus Prevotella compared with healthy controls73. Obesity-related hypertension is associated with alterations in oral and gut microbiota and elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines, suggesting that microbial interactions may lead to elevated blood pressure through systemic inflammatory responses74. Additionally, correlations between oral and gut microbiota and plasma metabolites, such as sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P), suggest that microbes might influence blood pressure through S1P-associated pathways71. Moreover, microbially derived metabolites such as TMAO enhance angiotensin II-induced vasoconstriction, further linking the oral-gut axis to hypertension75.

Since sodium absorption primarily occurs in the intestine, the gut microbiome may affect salt sensitivity, which is a known risk factor for hypertension. In hypertensive rats fed a high-salt diet, an increase in Erwinia and Corynebacteriaceae, alongside a decrease in Anaerostipes, was observed, indicating gut microbiota involvement in blood pressure regulation76. High-salt diets also reduced Bacteroides fragilis and arachidonic acid levels in the intestine, contributing to elevated blood pressure via increased corticosterone levels77.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most representative cardiometabolic diseases, characterized by significant metabolic disturbances, including persistent hyperglycemia and insulin resistance, and severe cardiovascular target organ damage78.

Microbiota composition in diabetic patients exhibits significant differences compared to non-diabetic individuals, affecting both the oral and gut ecosystems. In the oral cavity, patients with diabetes show an increased abundance of Actinomyces, Selenomonas, Veillonella, Prevotella, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Leptotrichia, Lactobacillus, Neisseria and Streptococcus, while Alloprevotella and Acinetobacteria are decreased79,80,81. Periodontitis-associated microbial changes contribute to systemic inflammation and metabolic disorders during the progression of diabetes82. A systematic assessment showed that severe periodontitis increased the incidence of diabetes by 53%83.

The intestinal translocation of the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis has been shown to trigger insulin resistance, emphasizing the role of oral-gut microbiota dysbiosis in systemic metabolic dysfunction84. In the gut, insulin-resistant participants showed a decrease in Bacillota and an increase in Bacteroidota85. Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, and Faecalibacterium were negatively correlated with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), while Ruminococcus and Fusobacterium were positively correlated with T2DM86. Gut flora may also mediate the effects of periodonontitis on systemic diseases, including pre-diabetes87. A findings indicate dysregulation of the oral-gut microbiota axis in patients with diabetes, characterized by an increase in oral Fusobacterium nucleatum and gut Lactobacillus. Further studies suggest that this dysregulation is closely associated with diabetic heart disease88. Additionally, studies have shown that an increase in the number of Bacteroides fragilis decreased the abundance of Lactobacilli and increased the abundance of Desulfovibrionaceae, resulting in the disruptions of glucose or lipid metabolism and enhanced inflammatory responses89.

A small increase in blood microbiota-derived LPS has been identified as a key factor in triggering low-grade inflammation, leading to insulin resistance in obesity-related cardiometabolic disorders90. Acetate activates the parasympathetic nervous system, increasing glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and the secretion of growth hormone-releasing peptides, potentially causing hyperphagia and obesity91. Propionate enhances catecholamine-mediated counter-regulatory signaling of insulin, contributing to insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia92. The upregulation of the glycine degradation pathway in oral and intestinal microbiota reduces serum glycine levels, promoting insulin resistance93. Additionally, gut microbial metabolites such as tryptamine and phenylethylamine impair insulin sensitivity in metabolic syndrome94.

Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia, a critical contributor to cardiometabolic diseases development95, is closely linked to dysbiosis in oral and gut microbiota96,97. Patients with periodontitis caused by the imbalance of microecosystems have decreased levels of HDL and increased levels of LDL and TG98. Periodontal pathogens, their metabolites, and pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by periodontal infections may contribute to various lipid metabolism disorders and lipid peroxidation99. In the microbial communities of the oral cavity of atherosclerotic patients, the abundance of Fusobacterium was positively correlated with LDL and TC levels, and the abundance of Streptococcus was positively correlated with HDL and apolipoprotein A1 levels100. The oral administration of Fusobacterium nucleatum significantly elevated the plasma triglyceride and cholesterol levels in ApoE−/− mice fed a high-cholesterol diet, promoting the onset and development of atherosclerosis101.

Experimental periodontitis in hyperlipidemic mice demonstrated more pronounced gut microbiota dysbiosis, characterized by increased inflammation and impaired intestinal function. Non-surgical periodontal treatment improved gut microbial composition, restored gut barrier integrity, and mitigated systemic lipid metabolic disturbances, highlighting the importance of oral-gut microbiota axis in hyperlipidemia102.Imbalances in the intestinal flora may induce oxidative stress, activating NLRP3 and triggering an inflammatory response, ultimately leading to dysfunction of the vascular endothelium and disruptions in glucolipid metabolism103. A study found that germ-free mice showed greater resistance to obesity induced by consumption of a high-fat diet and excreted high amounts of lipids in their feces, thereby altering cholesterol metabolism104. The colonization of the “obese microbiota” in germ-free mice resulted in a more significant increase in total body fat compared with the colonization of the “lean microbiota”105. These observations underline the influence of microbiota composition on lipid metabolism.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD), formerly known as Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) is a phenotype of liver disease associated with metabolic syndrome106. Like other metabolic conditions such as obesity and diabetes, MAFLD has systemic implications that extend beyond the liver, significantly increasing cardiovascular risks107.

Oral microbiota dysbiosis is a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of chronic liver diseases, including MAFLD. Studies have shown that the salivary microbiota of MAFLD patients has a higher abundance of Howardella, Treponema, Desulfobulbus, Bulleidia, Propionibacterium, and Filifactor compared to healthy controls108. MAFLD patients exhibit reduced species richness and diversity in their gut microbiota. At the phylum level, the relative abundance of Bacteroidota, Pseudomonadota, and Fusobacteriota is increased, while Bacillota is decreased. At the genus level, the relative abundance of Prevotella, Bacteroides, and Escherichia-Shigella is elevated109.

Notably, Porphyromonas gingivalis, a well-known periodontal pathogen, has been identified as a direct risk factor for MAFLD110. Porphyromonas gingivalis and its LPS can translocate from the oral cavity to the gut, causing gut dysbiosis111, which is linked to increased hepatic expression of TLR2, TNF-α, and IL-17, thereby promoting liver inflammation112. It can also accelerate fibrosis by activating hepatic stellate cells, thereby contributing to the progression of MAFLD113. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, another periodontal pathogen, has also been implicated in MAFLD development by altering gut microbiota and affecting glucose metabolism114. Periodontitis-induced dysbiosis has systemic effects, including endotoxemia and altered serum metabolome, which contribute to hepatic inflammation and steatosis, thereby worsening MAFLD111.

Fatty liver-related gut dysbiosis is marked by reduced beneficial bacteria and increased pro-inflammatory bacteria, disrupting metabolism, immune function, and mucosal barrier integrity, and heightening susceptibility to opportunistic pathogens115. Impaired gut barrier function facilitates the translocation of pathogens, bacterial endotoxins, and other inflammatory mediators into the portal vein, ultimately reaching the liver116. Oral bacteria or their byproducts may also disseminate to the liver, exacerbating MAFLD117. Gut microbiota-derived components (e.g., LPS, peptidoglycan) and metabolites (e.g., SCFAs, TMAO) interact with hepatocytes via the portal vein, influencing glucose and lipid metabolism, immune responses, and redox balance, thereby driving MAFLD progression118.

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease and a major contributor to cardiometabolic diseases119. Microbiome imbalances contribute to foam cell formation, atherogenic lipid accumulation, and accelerated plaque progression120.

Oral bacteria can easily enter the circulatory system and induce low-grade inflammation, a widely recognized risk factor for atherosclerosis121. A study identified Streptococcus mutans in all oral samples (100.0%) and atherosclerotic plaques (100.0%), suggesting that this bacterium, originating from the oral cavity, likely reached the atherosclerotic plaques through the hematogenous pathway122.

Porphyromonas gingivalis evades host immune clearance and enters the circulation in various forms along with blood and lymphatic fluids to colonize the arterial walls. This colonization directly induces local inflammation in blood vessels and disrupts lipid profiles, thus contributing to the progression of atherosclerosis123. Translocation of oral bacteria, including Porphyromonas gingivalis, to the gut disrupts the microbiome, significantly reducing alpha diversity and beneficial bacteria like Akkermansia and Clostridiaceae. This dysbiosis impairs gut barrier integrity, increasing susceptibility to pathogen colonization124. Additionally, Porphyromonas gingivalis induces smooth muscle cell apoptosis and inhibits macrophage pinocytosis125, while affecting endothelial progenitor cell angiogenesis through the Akt/FoxO1 signaling pathway, further contributing to plaque instability and progression126.

Streptococcus constitutes the predominant bacterial population in the oral cavity, and an increased abundance of Streptococcus in the gut has been associated with coronary atherosclerosis and systemic inflammatory markers127. Research indicates that Streptococcus mutans may promote atherosclerosis by adhering to type I collagen, inducing platelet aggregation, invading endothelial cells, and increasing interleukins, MCP-1, and foam cell formation122. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection in the oral cavity affects the expression of surface markers on endothelial cells and regulates vascular endothelial growth factor receptors, leading to impaired tissue vascularization during inflammation128. This bacterium promotes intestinal inflammation by activating TLR4 and NF-κB, enhancing systemic inflammation and accelerating atherosclerosis101,129. The gut bacteria associated with coronary atherosclerosis, such as Streptococcus anginosus and Streptococcus parasanguinis, have been detected in oral saliva samples, emphasizing their correlation with poor dental health127. One study found that the gut flora may mediate the effects of chronic endodontic apical periodontitis on atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice130.

The deterioration of barrier function, dysregulation of microecology, and amplification of pathogenic bacteria may lead to an increase in the levels of pro-atherosclerotic metabolites such as LPS and TMAO131. The gut microbiota metabolite TMAO indirectly promotes atherosclerosis-associated inflammation through ROS stimulation and signaling involving AMPK and SIRT1132. Moreover, elevated ROS levels may enhance cardiac remodeling by inducing hypertrophic signaling and apoptosis133, accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis134.

Coronary heart disease

Coronary heart disease (CHD), a typical example of cardiometabolic diseases, represents the ultimate manifestation of accumulated metabolic dysregulation135. Its progression is closely associated with disruptions in the oral-gut microbiota axis. Microbial imbalances impair metabolic function, weaken immune regulation, and compromise barrier defenses, thereby exacerbating systemic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction, a key drivers of CHD development and progression74,84,99,123.

The translocation of microbiota is a critical trigger in the development of CHD. Pathogenic bacteria can migrate to the gut via the enteric, hematogenous, or immune pathways, leading to gut microbiota dysbiosis46,59,124. This dysbiosis compromises gut barrier integrity, allowing translocated oral bacteria and their metabolites to enter systemic circulation. These substances activate immune responses, stimulate the production of inflammatory cytokines, disrupt glucose and lipid metabolism, exacerbate endothelial damage and atherosclerosis, thereby accelerating CHD progression136. This translocation effect is further amplified in the context of metabolic disorders such as hyperlipidemia and diabetes, creating a vicious cycle88,102.

The microbiota metabolite TMAO exacerbates oxidative stress by decreasing the levels of superoxide dismutase, increasing the levels of malondialdehyde and glutathione peroxidase, and producing pro-inflammatory cytokines137. This process accelerates endothelial cell senescence and vascular aging through oxidative stress138,139. Microbiota-derived N,N,N-trimethyl-5-aminovaleric acid accelerates cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting carnitine synthesis and the subsequent fatty acid oxidation140. Imidazole propionate activates the p62/mTORC1 pathway in hepatocytes and primary hepatocytes, increases insulin resistance141, and promotes myocardial injury via the myocardial p62/mTORC1 pathway142.

To further elucidate the relationship between specific microorganisms and multiple cardiometabolic diseases, we have summarized the relevant changes in Table 2.

Interventions targeting oral-gut microbiota axis

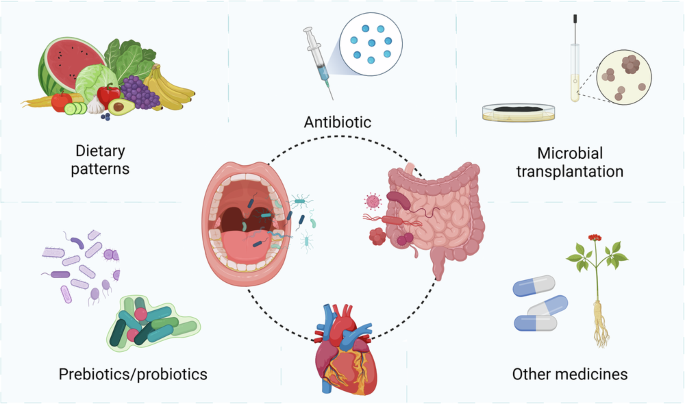

Targeting the oral-gut microbiota axis offers a promising approach to alleviating cardiometabolic diseases risks and minimizing future cardiovascular events143,144. A healthy microbiota supports cardiovascular health by providing essential nutrients, improving barrier function, enhancing immune responses, clearing cellular debris, and expelling toxins145,146. Interventions targeting the oral and gut microbiota include specific dietary patterns, taking prebiotics/probiotics, undergoing microbial transplantation, using antibiotics, and utilizing other medicines147,148 (Fig. 4).

Improving the microbial balance in the oral and gut is beneficial for Cardiometabolic health. Key intervention strategies focusing on the microbiota include dietary patterns, prebiotics/probiotics, microbial transplantation, antibiotics, and other medicines. Created with BioRender.com.

Dietary patterns

Long-term dietary intake is a direct driver of oral and gut microbiota, affecting the structure and activity of trillions of microorganisms in the body149. Studies have shown that dietary interventions (including normal diet, sucrose, dairy products, and vegetables) lead to significant changes in oral microbiota composition150. The consumption of higher-quality carbohydrates has been associated with improved cardiometabolic health, potentially mediated by the presence of metabolism-friendly flora151. High-fiber diets and acetate supplementation can alter the composition of the gut microbiota, thereby preventing the onset of hypertension and heart failure152. Additionally, high-fiber diets have shown positive effects on glucose homeostasis and systemic inflammation in individuals with T2DM153. A high 12-component modified Japanese Diet Index (mJDI12) significantly increased dietary fiber intake, which in turn increased butyrate-producing bacteria in the gut and reduced Alloprevotella in the oral microbiota, highlighting the benefits of a balanced diet on both oral and gut health154. Recent studies have shown that dietary interventions targeting prediabetic individuals can induce significant changes in both oral and gut microbiota, which are closely associated with blood glucose regulation, metabolic health, and immune responses, further validating the potential of dietary interventions in improving cardiometabolic health155. SCFAs, the major intestinal metabolites of dietary fiber, attenuate intestinal dysbiosis and hypertension. They also restore the balance between immune-associated Th17 cells and Tregs156. Dietary supplementation with branched-chain amino acids can alleviate dyslipidemia and inflammation by influencing the gut microbiota, thereby reducing high-fat diet-induced atherosclerosis157.

Prebiotics/probiotics

Probiotics are effective in improving heart health by establishing a healthy gut microbiome or supplementing with its metabolites158. Probiotics are defined as live strains of microorganisms that, when used in sufficient amounts, provide health benefits to the host159. By contrast, prebiotics are substrates that are selectively utilized by host microorganisms to confer health benefits160. The lack of prebiotics predisposes mice to hypertension, consequently leading to pathological cardiac remodeling161. Konjac glucomannan, a natural soluble dietary fiber, acts as a prebiotic by enhancing gut microbiota abundance, increasing probiotic numbers, and promoting SCFA production, thus maintaining gut homeostasis162. The probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum induces Nrf2-mediated antioxidant signaling and eNOS expression, thereby improving myocardial diastolic function163. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG improved the gut microbiota and the peripheral blood metabolome, increased the abundance of beneficial bacteria, and attenuated endothelial damage and the formation of atherosclerotic plaques164. It also exerted protective effects against myocardial dysfunction in obese mice with intermittent hypoxia by upregulating the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathways165. Furthermore, the enteric probiotic Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG improved periodontal bone regeneration in patients with periodontitis and hyperlipidemia by modulating the intestinal microbiota and increasing the expression of bone-enhancing metabolites in the blood166. Lactobacilli may ameliorate T2DM-related periodontitis by maintaining the gut barrier function167. The intestinal probiotic Akkermansia muciniphila protects the epithelial barrier, maintains flora homeostasis, and improves metabolism. It inhibits Fusobacterium nucleatum-induced inflammation in gingival epithelial cells by regulating inflammatory factor secretion through the TLR/MyD88/NF-κB pathway168.

Microbial transplantation

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is an effective strategy for restoring gut microbiota of patients by transplanting beneficial flora from the feces of healthy individuals into their intestines169. FMT has shown great potential in treating various metabolic and cardiovascular conditions. By restoring gut microbiota balance, FMT can improve metabolic markers, reduce systemic inflammation, and enhance overall gut health170. In patients with T2DM, FMT significantly improved gut microbiota composition, insulin resistance, and body mass index171. In animal studies, FMT significantly increased the intestinal flora diversity in hypoxic rats, which improved cardiac hypertrophy to a certain extent172. FMT with feces from normal mice restored gut microbiota and barrier function, reduced the pathogenicity of the oral microbiota, reversed the Th17/Treg imbalance in periodontal tissue, and alleviated alveolar bone loss173. Based on the positive outcomes of the ECOSPOR III trial (SER-109 versus Placebo in the Treatment of Adults with Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection), the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved SER-109174, the first oral fecal microbiota drug.

Inspired by the success of FMT in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders, oral microbiota transplantation (OMT) has also been proposed175. Studies indicate that OMT significantly reduced periodontitis-associated pathogenic microbial specie and increased beneficial bacteria176. OMT ameliorated oral mucositis in mice, reconstructed the oral and gut bacteria configurations, and reprogrammed the gene expression profile of tongue tissues177. A study on beagle dogs with periodontitis demonstrated that OMT can serve as an adjunct to mechanical and chemical full-mouth debridement, providing additional modulation of the oral microbiota composition in these dogs178.

Given the positive outcomes observed in existing studies, microbiota transplantation holds great potential for future clinical applications. However, research on microbiota transplantation remains limited, and uncertainties persist regarding its effects on microbiota from different ecological niches, the optimal transplantation dose, long-term clinical effects, and safety.

Antibiotics

Antibiotic treatment has a significant effect on the microbiota. Broad-spectrum antibiotics may alter the gut microbiota to improve the outcome of stroke in rats179. In a mouse model, ampicillin treatment reduced the levels of LDL and VLDL levels, the risk factors for atherosclerosis, resulting in fewer aortic atherosclerotic lesions180. Invasive dental procedures with antibiotic prophylaxis have been shown to significantly reduce infective endocarditis events181. However, excessive use of antibiotics can lead to gut dysbiosis, affecting the Th17/Treg balance and disrupting the oral microbiota. This imbalance may increase the abundance of periodontitis-associated pathogens, reduce probiotics, and upregulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, ultimately exacerbating periodontitis173. Studies have shown that antibiotic use disrupts the oral microbiome balance, significantly affecting the composition, diversity, and metabolic function of the oral microbiota in rats182. In addition, the misuse of antibiotics and the development of bacterial resistance are issues that should not be overlooked. Therefore, the advantages and disadvantages must be carefully evaluated when considering the use of antibiotics.

Other medicines

Microorganisms in the digestive system may directly participate in the absorption and metabolism of medicines. Cagliflozin (Cana) was effective in improving glucose metabolism disorders in patients with T2DM, which may be attributed to the restoration of the balance between the gut and oral microbial communities. Treatment with Cana increased the relative abundance of SCFA-producing bacteria in the intestine and a significant increase in Prevotella and Veillonella in the oral cavity183. Metformin, a drug widely used in the treatment of diabetes, has been found to exert its antidiabetic effects by changing the gut microbiota, partially restoring the gut dysbiosis associated with T2DM184. Aspirin ameliorates immune inflammation in atherosclerosis by modulating the Treg/Th17 axis and CD39-CD73 adenosine signaling through the remodeling of gut microbiota in ApoE−/− mice185. Monomers and compounds of Chinese herbal medicine may also improve coronary heart disease and mitigate the associated risk factors by modulating the gut microbiota186. Tongxinluo capsules reduced the inflammatory response, inhibited the NLRP3 inflammatory pathway, and improved the stability of plaque by improving the gut microbiota and increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria and the contents of beneficial metabolites187. Dengzhanshengmai capsule reduced systemic inflammation, improved the intestinal barrier function, and enhanced the cardiac function in rats with heart failure188. These studies provide robust evidence supporting the potential to improve cardiometabolic health by targeting the microbiota.

Future perspectives and research directions

The oral-gut microbiota axis is an emerging field, with increasing evidence highlighting its role in cardiometabolic health. However, several critical gaps remain in our current understanding. The molecular pathways of oral and gut microbiota interactions are still unclear due to the complexity and diversity of microbial communities and their effects on host metabolism and immune responses. Most studies are observational and cross-sectional, providing a static perspective and failing to explore underlying mechanisms. This limits our understanding of how microbial shifts contribute to cardiometabolic diseases. Moreover, current research often isolates oral or gut microbiomes rather than examining their combined effects, missing a holistic view of their impact on health. Many studies rely on animal models or small human cohorts, which may not fully represent the complexity of human microbiota interactions.

Future research should focus on elucidating the molecular mechanisms of the oral-gut microbiota axis, identifying key microbial metabolites and signaling pathways involved. Longitudinal studies tracking changes in oral and gut microbiota, combined with advanced multi-omics techniques, will provide deeper insights into how these interactions influence cardiometabolic diseases. Developing therapeutic strategies based on microbiota modulation, personalized to individual microbiota profiles, could optimize treatment outcomes and minimize side effects.

In conclusion, the oral-gut microbiota axis represents a promising target for improving cardiometabolic health, with further research needed to translate these findings into clinical applications.

Responses