The physiological characteristics and applications of sialic acid

Introduction

Sialic acid (SA), a crystalline reducing acid, was first isolated from bovine submaxillary mucin1. Nowadays, approximately 80 neuraminic acid derivatives have been classified2. They are widely found in animals (from echinoderms to higher animals), microorganisms, and insects, but not in higher plants2. Despite the size of the family, current studies have mainly focused on three core structural derivatives: N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac), N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc), and deaminoneuraminc acid (KDN). They usually occupy the far end of the glycan chain, making them particularly susceptible to interactions with other cellular and environmental factors. Host SA is mainly derived from endogenous synthesis and exogenous intake. Some endogenous SAs are synthesized by the liver, exist in large quantities in various parts of the body (such as the brain and colon)3, and play roles in promoting host neural development, enhancing memory, and regulating immunity. Neu5Gc is hydroxylated from CMP-Neu5Ac to CMP-Neu5Gc by CMP-Neu5Ac hydroxylase (CMAH)4. However, because of mutations in CMAH, humans lose the ability to biosynthesize Neu5Gc, which is in trace amounts in healthy individuals4, except in some patients. Therefore, foods such as red meat, milk products, and bird nests have become important sources of exogenous SA in the host5,6,7.

The important role of SA in affecting host physiological and pathological processes includes information transfer between cells, cell adhesion between, regulation of the life cycle, mediation of bacterial and viral infections, and involvement in tumor growth and metastasis. Of note, the diversity of SAs determines the diversity of their biological functions in human nutrition, and they have become potential targets for ameliorating some diseases. The presence of Neu5Gc is often closely related to the occurrence and development of diseases, such as cancer8. Neu5Ac is an important source of nutrients for brain development and cognition, particularly in infants and young children9. These results indicate that different types of SA have specific effects on host health. Considering the current lack of SA safety evaluation data, a detailed understanding of the source, structure, and physiological functions of different SA types is of great significance for developing SA products.

In this review, the three most widely studied types of SA, namely Neu5Ac, Neu5Gc, and KDN, were selected as the main research objects, focusing on their distribution in the host. Their metabolic processes and physiological functions in the human body are also discussed. In addition, the contents of SA in the external environment, especially in food, are summarized to clarify the application potential of different SAs in developing functional foods. Finally, the safety evaluation, application status, and future application prospects of SAs are analyzed, to facilitate the rational utilization of SA and the development of functional food components.

Distribution of SA

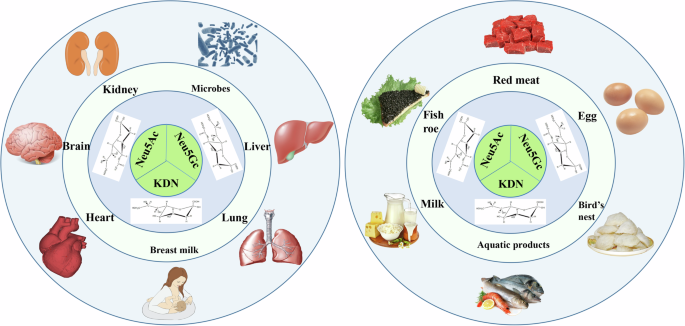

The distribution of different SAs in nature (especially in the host’s body) is significantly different, and this is attributable to the variation in external factors, such as diet types, and the physiological and developmental state of the host. Therefore, understanding the distribution of different SAs in the host and external environment is of great significance for the rational utilization and targeted regulation of different SAs (Fig. 1).

Neu5Ac N-acetylneuraminic acid, Neu5Gc N-glycolylneuraminic acid, KDN deaminoneuraminc acid, SA sialic acid. The image is created by the author and there is no copyright or conflict of interest.

Neu5Ac

Neu5Ac is widely distributed in nature, mainly as a component sugar in animal cell membranes, secreted fluid glycoproteins, glycolipids, and bacterial capsule substances. In the human body, Neu5Ac is primarily concentrated in the central nervous system, especially in the brain’s gray matter, where it combines with gangliosides and glycoproteins. It is an important structural and functional ganglioside component and correlates with brain growth and memory formation10,11. Neu5Ac could be detected in almost all tested organs and was the predominant type of SA distributed in animals12. In the gut, Neu5Ac plays a variety of biological roles at the interface of host epithelial cells and the microbiota. It is the most abundant SA type in adult and fetal mucins13. Many bacterial pathogens can mimic the host through cell surface decoration and provide structural building blocks to evade the host immune system14.

In food, SA exists mainly in a conjugated state and it binds to complex polysaccharides on the cell surface. Human milk is one of the richest sources of SA, primarily Neu5Ac. Most SA in breast milk is present in a conjugated state (oligosaccharide-conjugated), with a small amount remaining in the free state15. Edible bird nests are the main source of Neu5Ac7. In addition, it exists in large quantities in poultry eggs16, livestock meat17, and other foods, which is the most widely distributed SA type in food.

Neu5Gc

Neu5Gc is present in non-human primate cells, including some extant great apes, as well as many other mammals and invertebrates18,19, and salmonid fish eggs20. Mutations in the CMAH gene cause humans to lose the ability to biosynthesize Neu5Gc, which is virtually absent in healthy individuals4. Notably, Neu5Gc accumulates in large amounts in the human body under certain pathological conditions, especially in some inflammatory and neoplastic diseases, and it may be involved in physiological responses in the human body21,22,23.

Exogenous dietary intake is considered the main source of Neu5Gc in the human body. Dietary sources rich in Neu5Gc include red meat (beef, pork, and lamb) and some milk products, it is largely absent in plants, microbes, poultry, and fish5. When healthy humans ingest foods containing Neu5Gc, sialidase produced by their intestinal flora can metabolize glycans and release free Neu5Gc from the food24. Some free Neu5Gc is absorbed and excreted in urine, and other exogenous Neu5Gc reaches lysosomes via the pinocytic/endocytic pathway. It is exported in free form to the cytosol for activation and transfer to glycoconjugates25. It is then incorporated into the surface or secreted glycans, glycoproteins, and glycolipids of cultured human cells. Current studies have proposed two possible mechanisms for the abnormal accumulation of Neu5Gc in the body. First, individual differences lead to variable susceptibility or resistance to some microbial pathogens, which then affects the function of some endogenous SA receptors in the immune system. Second, excessive dietary intake of Neu5Gc may also lead to disturbances in the SA synthesis pathway and excessive accumulation of Neu5Gc in the body, triggering antigenic reactions.

KDN

KDN, which was first identified in 1986 as an unknown deaminated SA in Salmo gairdneri (rainbow trout) egg polysialoglycoprotein, protects oligo(poly)sialyl chains from exo-sialidase26. Early studies suggested that KDN is prevalent in some lower vertebrates and bacterial capsular polysaccharides27. Studies based on some mammals have found that, although KDN has been detected in the spleen, kidney, heart, and muscle, its amount is <1% of the total SA content12.

KDN is a type of SA that is closely related to the occurrence and development of host diseases. KDN was identified in human fetal umbilical cord red blood cells and ovarian cancer cell samples and is overexpressed in ovarian tumor tissues27,28,29. Although direct evidence is lacking, these findings suggest that KDN synthesis is involved in blood cell formation during animal reproduction and embryonic development. In addition, overexpression of KDN in ovarian and prostate cancer cells suggests that it may be an oncoembryonic antigen in these tumors that may develop as an “early warning” signal for disease onset and/or a key marker of disease recurrence29.

Importantly, significant changes in KDN levels within the body are strongly influenced by dietary intake. Oral mannose intake results in significant intracellular KDN enrichment in the spleen, lungs, kidneys, and brain. These findings suggest that dietary mannose affects KDN metabolism in various organs and highlight the possibility that the targeted regulation of dietary SA content protects host health30.

Synthesis and metabolism of SA in human

SA is internally synthesized by the liver3. The UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase is a key enzyme affecting the hepatic synthesis of Neu5Ac31. However, owing to immature liver development and the low activity of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase in newborn individuals, the amount of SA synthesized may not meet the demand for SA during early brain development32. Thus, exogenous SA is necessary, such as through maternal milk, to meet the needs of normal growth and development. Another major source of SA is placental transfer to the host offspring. Since fetal mice cannot produce SA, SA in pregnant mice may enter the fetus through the placenta to ensure fetal growth and development. Thus, the placenta can regulate the balance of SA content between the mother and fetus16.

Some of the SA in the body comes from exogenous intake, and the small intestine is the main site of SA uptake. After oral administration to rats, 90% of the administered Neu5Ac is absorbed from the intestine within 4 h. After intravenous administration, 90% of the administered Neu5Ac is excreted in the urine within 10 min33. Some Neu5Ac may reach the colon, where it can be catabolized by the microbial community and the host, thereby affecting the physiological state and microbiome structure of the gut34.

Physiological function

Maintenance of brain health

In 1981, Morgan et al. injected radiolabeled Neu5Ac into 12 day-old pups and found that 80% of the Neu5Ac was incorporated into the synaptosome after 2 h35. The same phenomenon was observed in male domestic piglets injected with Neu5Ac through the jugular vein. After 120 min, Neu5Ac was significantly enriched in the brain and its content was higher than in the liver, pancreas, heart, and spleen36. These results indicate that exogenous SA can cross the blood-brain barrier and enter various tissues, with significant enrichment in brain tissue. Previous studies have shown that 70% of conjugated SA in the brain tissue is in forming gangliosides9. As an important component of brain gangliosides and sialic glycoproteins9, SA combines with nerve cell adhesion molecules (NCAMs) to form polySA-NCAM, which complexes play important roles in synaptic plasticity and neurodevelopment9,37. Therefore, exogenous intake of SA may contribute to physiological health, and SA may be involved in the process of neural development.

SA is frequently attached at the terminal of complex oligosaccharides in glycolipids, glycoproteins, and mucin. Sialylated human milk oligosaccharides are a key component of exogenous SA to infants, which may be a conditioned nutrient during rapid brain growth, promoting infant memory and intellectual development, and improving children’s intestinal absorption capacity and immunity38. Human milk containing SA in the form of sialyllactose influenced bound SA in the prefrontal cortex and the ratio of free SA to bound SA in the hippocampus in pigs39, which is closely associated with cognitive and memory development. However, incomplete de novo SA biosynthesis leads to SA deficiency, which reduces the pool of conjugated SA precursors. For example, the newborn rat brain absorbs more SA than the adult brain, and SA supplementation improves cognitive function in adult mice40. SA supplementation in the neonatal period through exogenous sources (such as milk powder) targeted to the brain to promote ganglioside and NCAM formation is conducive to promoting appropriate neurological, cognitive, and memory development and has a great role in promoting memory improvement and intellectual development in infants16. Therefore, SAs, especially Neu5Ac, have the potential to be a component of infant formulations.

Tumor growth signals

Abnormal sialylation of the surface of tumor cells and significant upregulation of sialotransferase activity are recognized cancer markers that are thought to be associated with aggressiveness and metastatic potential41,42,43, and abnormal SA levels have the potential to be used as a cancer biomarker44,45,46. There are several possible pathways whereby SA affects tumor growth. First, SA can be used as a recognizable receptor to mask other molecules; therefore, it can be used to mask the antigen determinant on the surface of malignant tumor cells, which can reduce their immunogenicity and increase their survival. Sialoglycans are recognized by CD33-associated Siglecs to negatively regulate the immune response, thus impairing immune surveillance47. Second, sialidase, which is an enzyme that catalyzes the removal of SA residues from glycoproteins and glycolipids, plays an important role in many biological processes by regulating cellular SA content48. For example, α2,3-sialyltransferase type I regulates ovarian cancer cell migration and peritoneal dissemination via epidermal growth factor receptor signaling49. On this basis, the use of α2, 3-sialylation inhibitors can significantly inhibit the migration and spread of tumor cells, indicating an important association between sialylation and tumor occurrence and development49. Third, SA is an important component of gangliosides, and in several types of cancer, the overexpression of gangliosides leads to the activation of cell signaling, increased cell proliferation and migration, and tumor growth50. The O-acetylation of SA residues is one of the main modifications of gangliosides and is mainly dependent on the activities of sialyl-O-acetyltransferase and sialyl-O-acetylesterase. Overexpression of O-acetylated gangliosides is a marker of some cancers51, and alterations may also affect tumor immunity and metastasis. Ganglioside synthesis is increased in human hepatocellular carcinoma stem-cell-like cells, and the inhibition of ganglioside synthesis can inhibit the proliferation and spheroid growth of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. This is partly due to the inhibition of chromosomal segregation and mitotic-progression-related regulatory genes52, suggesting targeted regulation of the synthesis of SA and its related products (such as gangliosides) is expected to be useful for treating tumors. Fig. 2

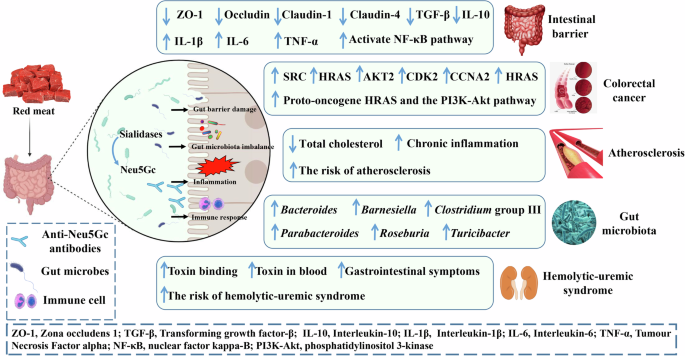

After dietary intake (such as red meat), Neu5Gc is released by sialidase produced by intestinal microbes, which further affects host health and disease. This mainly involves the following mechanisms (Fig. 2): (1) affecting intestinal barrier function, (2) regulating the structural composition of the intestinal flora, (3) inducing inflammation, and (4) inducing an immune response. The image is created by the author and there is no copyright or conflict of interest.

Therefore, in addition to the body’s synthesis of SA, the intake of exogenous SA appears to be related to the occurrence and development of a variety of tumors. Many studies have demonstrated that excessive red meat intake may be associated with a higher risk of various digestive tract diseases, such as colon and liver cancers53,54. Long-term consumption of red meat by human-like Neu5GC-deficient mice significantly increases the incidence of cancer by five-fold, which may be attributed to the presence of Neu5Gc in red meat21. Neu5Gc in red meat can induce the production of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies. The response of the total anti-Neu5Gc antibody population to Neu5Gc antigen epitopes may be related to chronic inflammation and the occurrence of colorectal cancer55. This is caused by the interaction of metabolically accumulated dietary Neu5Gc with circulating anti-Neu5GC antibodies56. Importantly, CMAH is a key gene in the synthesis of Neu5Gc, and the recent use of CMAH gene deletion in mice has provided the possibility of further exploring the relationship between Neu5Gc, inflammation, and related tumors4. Systemic inflammatory responses occur when mice are fed a diet containing Neu5Gc, leading to a significantly higher incidence of cancer21. These experimental results may explain why diet and its specific components are closely related to susceptibility to certain diseases. Fig. 3

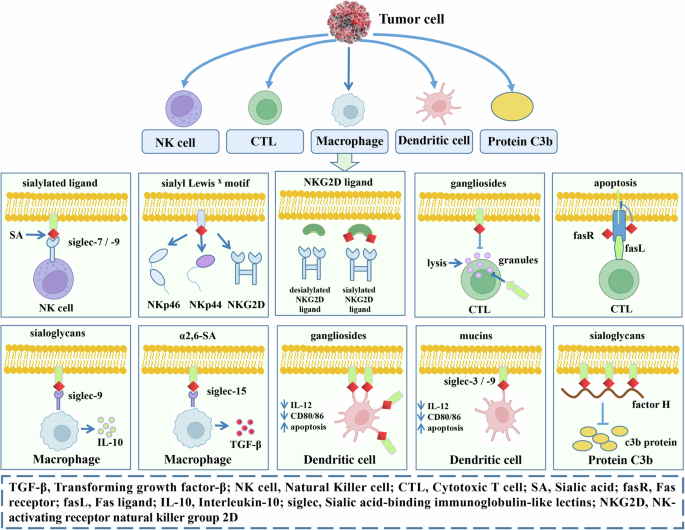

SA in cancer cells affects tumor immune evasion (Fig. 3). First, it protects them from being killed by natural killer (NK) cells. Siglecs expressed by NK cells bind to SA and inhibit its signal transduction. Sialyl Lewis X can be detected by activating the receptors NKp46, NKp44, and NKG2D, thereby inducing NK cell activation. NKG2D usually binds relative ligands, and sialylation of cancer cells reduces the NK-activating signals derived from tumor cells. Second, SA disables the main killing mechanism of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Hypersialylation of FasR desensitizes tumor cells to Fas-mediated cytotoxicity. CTLs expressing FasL can eliminate tumor cells that express FasR. Third, SA regulates the function of macrophages. Gangliosides influence the trafficking of lytic granules to immunological synapses and the free of lytic proteins. α2,6 SAs in some tumor cells stimulate the Siglec-15-dependent TGF-β production by monocytes nd macrophages. Expression of Siglec-9 in macrophages is capable of lowering TNF-α production and increasing IL-10 production. Fourth, SA inhibits the activation and function of dendritic cells. Tumor-bound or secreted salivary glycans regulate the activation and maturation of dendritic cells, thereby inhibiting the activation of antitumor T-cell responses. In addition, α2,6 SA-carrying mucin 2 can bind Siglec-3 and induce apoptosis of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Fifth, a central regulatory protein factor H binds to sialoglycans on the surface of host cells, which inhibits the deposition and expansion of the complement-activating protein C3b on the cell surface and downstream activation of the complement replacement pathway. The image is created by the author and there is no copyright or conflict of interest.

In addition, KDN may act as an oncofetal antigen in these tumors, and its enhanced levels in tumor cells are closely related to human cancer pathogenesis29,57. In these studies, increased levels of KDH, along with a higher KDH: Neu5AC ratio, were considered “early warning” signals or predictive markers for detecting potentially malignant phenotypes in ovarian and other human cancers. Although relevant reports are limited at present, it is still proposed that the possible mechanism of high KDN levels in tumor cells involves hypoxia, which is a common feature of locally advanced tumors and highly invasive metastatic cancer cells. Hypoxic human cancer cultures can enhance the mRNA expression levels and enzymatic activity of Neu5Ac 9-phosphate synthetase (NPS) and phosphomannoisomerase. Elevated NPS levels promote KDN synthesis58. Based on these results, targeting SA and its related products may be an effective strategy for alleviating tumor-related diseases. For example, the use of sialidase inhibitors, such as 2, 3-didehydro-2-deoxyneuramic acid in combination with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, can significantly inhibit the malignant biological behavior of tumor cells49.

Antiviral activity

SA, usually as terminal monosaccharides on different cell surfaces and as secreted glycoconjugates, can interact with bacteria and viruses to affect their function. SAs are involved in critical interactions with many different viruses (as well as other pathogens) at different stages of their infection and transmission cycles59. The first step in the viral life cycle is for virus particles to attach to the cell surface and then proliferate in the target cell. SA plays an important role in regulating virus-receptor interactions and appears to be associated with the increased virulence and infectivity of viruses60. Frierson et al. explored the role of SA binding in the pathogenesis of neuroviruses using animal models60. The results showed that SA-bound reoviruses (wild-type) showed stronger infectivity than the serotype 3 reovirus (mutant), which does not bind SA. In addition, the virus replicated in primary cultures of cortical neurons in an SA-dependent manner. Notably, neuraminidase treatment significantly reduces the infectivity and replication capacity of wild-type viruses in mice. The goblet cells and mucus are considered the main innate defense mechanism of the body61. SAs on the mucosal and cell surfaces can bind and trap viruses, preventing them from entering target tissues and removing bound virions through active processes mediated by mucociliary transport62. For example, the antiviral activity of ovomucin is closely related to its SA component, and free SA strongly promotes the binding of ovomucin to hemagglutinin (HA), thereby enhancing the interaction63. In addition to masking effects and regulating receptor interactions, SA o-acetylation of glycolipids has been shown to regulate immune cell development and activation. SA bound to the virus is involved in the maturation and activation of immune cells. O-acetylation of SA at the c9 site on B cells is necessary for the appropriate development and activation of these cells, and the 9-O-acetylation state of SA regulates the function of CD22, a Siglec that acts as a BCR signaling inhibitor in vivo64.

The acetylated form of SAs is prevalent in mammalian cells. Viruses encode SA-modifying enzymes (sialidases or esterases) that allow them to control viral replication and release with high specificity59. SAs are typically present at the endpoints of N- and O-glycoproteins, which perform important recognition responses to environmental factors, such as other cellular factors and/or pathogens. Viral sialidases have traditionally been defined as neuraminidase (NA) because they degrade Neu5Ac59. SA is the target of specific recognition by many viruses. It can mediate viral binding and cell infection, and can also act as a decoy receptor to bind virions and block viral infections59. Therefore, reducing SA levels on the cell surface by neuraminidase treatment has been shown to inhibit the entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus into Calu-3 human airway cells. This provides direct evidence that virus-SA interactions may contribute to virion attachment65. Further studies on viral-SA interactions are required to prevent zoonotic transmission. Host-derived SAs are closely associated with the virulence of certain viruses. SA plays a distinct role in the viral infection of host cells, which may be attributed to different modifications occurring in different viruses at different stages of their infection and transmission cycles59. Given the high variability of SA in individual animal cells and tissues, determining the functional diversity and pathways of action resulting from different virus-SA carbohydrate combinations is critical for understanding the complex effects of SA on viral systems59.

Marker of inflammatory diseases

Numerous studies have demonstrated that elevated total SA levels are associated with the pathogenesis of various inflammation-related diseases, such as atherosclerosis and chronic heart failure66,67,68. Gruszewska et al. showed that chronic viral hepatitis can affect the serum total SA concentration, which may be a useful marker for distinguishing chronic hepatitis B from hepatitis C69. Therefore, serum total SA content has been considered a marker of inflammation in patients with various inflammatory diseases. Further experiments have provided direct evidence of the relationship between SA and inflammation. Dietary Neu5Gc supplementation may promote inflammation, hepatocellular carcinoma, and hemolytic uremic syndrome23. However, Neu5AC appears to inhibit high-fat diet (HFD)-induced inflammatory responses70. In addition, intravenous administration of SA exerts a similar inhibitory effect on inflammation, significantly reducing lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxin levels, oxidative stress, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels, and associated inflammatory responses. Moreover, intravenous SA administration reverses histopathological changes in the liver71. These results highlight the potential role of SA in modulating inflammatory responses.

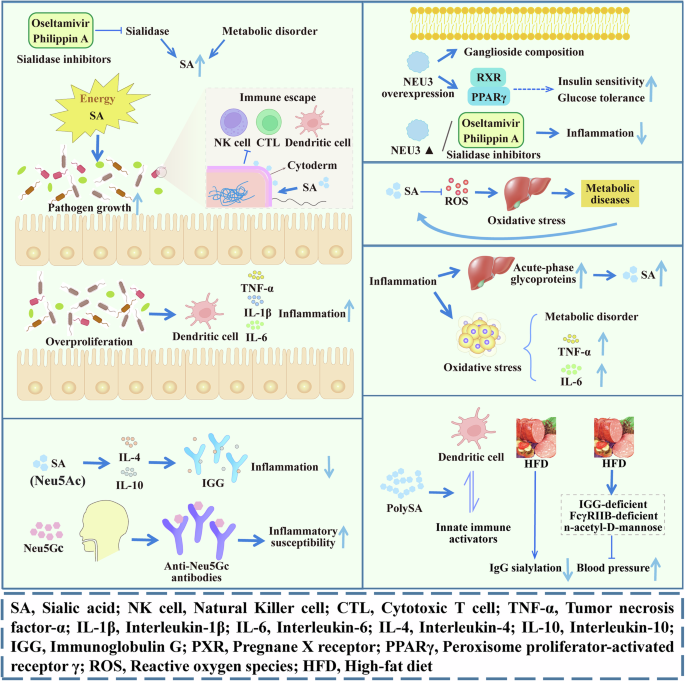

SA affects inflammatory diseases in several ways (Fig. 4). First, it acts as an energy source to promote the growth of pathogenic bacteria. SA derivatives located at the terminus of host glycans in the intestinal mucosa are sources of carbon and nitrogen for symbiotic and pathogenic bacteria, supporting their growth via the SA catabolic pathway. SA can also serve as a cell wall precursor that masks bacteria from host immune surveillance, further enhancing the viability and virulence of pathogenic bacteria72,73. For example, sialidase activity in the gut mediates the release of SA from intestinal tissues, thereby promoting the growth of Escherichia coli during inflammation. Excessive proliferation of E. coli may stimulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by intestinal dendritic cells, thus exacerbating the inflammatory response74. Similarly, excess SA levels, induced by abnormal SA metabolism in TP53-mutated zebrafish, can be ingested by Aeromonas species, which promotes their excessive growth. Aeromonas species colonize the intestine and induce intestinal inflammation in TP53-mutated zebrafish75. These results indicate that SA may induce inflammation through the accumulation of pathogenic bacteria in a specific environment. Notably, the sialidase inhibitors oseltamivir and Philippin A are effective at blocking the increased inflammatory response caused by dysbiosis and prevent the overgrowth of sialic-utilizing pathogens by reducing the availability of free SA75. Therefore, the manipulation of SA metabolism may provide an effective treatment strategy for gut microecological disorders and inflammatory diseases caused by related pathogens. Second, SA affects host immunity. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) exhibits distinct effects on regulating the immune response (pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory), which may be attributed to certain residues in the sugar portion attached to the constant fragment of IgG76. SA can reduce the immune response of glioblastoma cells by increasing the expression levels of anti-inflammatory factors, such as IL-4 and IL-1077. These results indicate that SA may be directly and/or indirectly involved in regulating the immune response, which in turn affects the body’s inflammatory response. In addition, exogenous SA, as an antigen, can produce an immune reaction in the body. Since Neu5Gc is not synthesized in humans, exogenous Neu5Gc can react with circulating anti-Neu5GC antibodies78. The resulting antigen-antibody interaction may explain the association between a Neu5GC-rich diet and susceptibility to inflammation and related diseases.

SA regulates inflammation by promoting the growth and proliferation of pathogens and regulating the immune response. SA and its related proteins regulate body metabolism through peroxidation stress, inflammation, and immunity. SA Sialic acid, NK cell Natural Killer cell, CTL Cytotoxic T cell, TNF-α Tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1β Interleukin-1β; IL-6 Interleukin-6, IL-4 Interleukin-4, IL-10 Interleukin-10, IGG Immunoglobulin G, PXR Pregnane X receptor, PPARγ Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, ROS Reactive oxygen species, HFD High-fat diet. The image is created by the author and there is no copyright or conflict of interest.

Effects on metabolic diseases

SA and its related metabolic enzymes are important indicators of the pathophysiology of metabolic diseases. Understanding the synthesis and catabolic patterns of SA can deepen our knowledge of the pathophysiology of metabolic diseases. The liver is an important site for synthesizing and glycosylation of glycoproteins and glycolipids. The physiological state of the liver largely influences changes in the sialylation patterns of glycoproteins and glycolipids. Liver disease may affect the serum concentrations of certain carbohydrate derivatives, especially SA, attached to the ends of oligosaccharide chains69. The release of SA from the glycolipid terminal residues of cell membranes may be due to cell membrane rupture and/or lipid oxidation, and the released SA enters the bloodstream. Increased SA levels reflect changes in the structural integrity of glycolipids in cell membranes and are associated with pathological states79. On this basis, a large amount of pre-clinical and clinical trial data supports the use of serum SA content as an important indicator of metabolic diseases80,81,82.

Several possible mechanisms underlying the influence of SA on metabolic diseases have been proposed (Fig. 4), including the role of sialidase, inhibition of oxidative stress, influence of metabolism-related inflammatory responses, and immune regulation. SA is important for the function of insulin receptors83. During insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and type 2 diabetes, increased SA synthesis in the liver and kidney results in the release of more SA into the bloodstream during cell renewal84. Correspondingly, altered levels of SA and its related enzymes can lead to altered insulin signaling85,86. For example, impaired insulin sensitivity in the skeletal muscle and liver is associated with decreased NEU3 protein abundance87, and NEU3 overexpression in the liver improves insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance by altering ganglioside composition and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma signaling85. Mice lacking NEU3 have reduced HFD-induced adipose tissue accumulation and liver inflammation compared to normal mice, and the injection of sialidase inhibitors can achieve similar effects88. These data suggest that sialidase regulates fat and liver tissue inflammation and that sialidase inhibitors are potential therapies for inflammation caused by an HFD.

Oxidative stress is one possible mechanism through which serum SA levels influence metabolic disease. While SA is located mainly at the outermost end of the glycan chain of all cell types, released SA acts as an active oxygen scavenger89 to reduce oxidative stress. Increasing evidence supports the central role of inflammatory factors in the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases. An HFD leads to excessive lipid storage in adipocytes, the production of stress signals, and the disturbance of metabolic function, which induces inflammatory responses90. IgG sialylation is reduced in HFD-fed mice, and transferring it to IGG-deficient mice results in increased blood pressure, while no hypertensive response occurred in mice lacking FcγRIIB. Supplementation with the SA precursor n-acetyl-D-mannose inhibits obesity-related hypertension induced by an HFD in mice91, suggesting that SA influences metabolic diseases by modulating immunity.

Regulation of the gut microbiota

SA may be utilized by sialidases encoded by intestinal microbial genes, thus regulating the structure of the intestinal flora. Sialidase cleaves these terminal residues from the sialic-binding substrate that can be used as a metabolic substrate for intestinal bacteria adapted to the mucosal environment. Increased sialidase activity in the gut mediates the release of SA from intestinal tissues, which is then utilized by intestinal microbes. Some native microbes such as Bifidobacterium, a symbiotic organism in the gut, can degrade milk gangliosides and release SA, thus playing a probiotic role in the gut92.

SA intake also has a regulatory effect on intestinal microbes. Under homeostatic conditions in the gut, SA binds to mucus. A small amount of free SA is present in the intestinal lumen, which is then degraded by symbiotic bacteria that can degrade polysaccharides. In Cmah−/− mice, which cannot synthesize Neu5Gc, a Neu5Gc-rich diet induces significant changes in the gut microbiota, enriching Clostridiales and Bacteroidales24. Ma et al. found that oral SA administration increased the relative weight of the liver and decreased serum aspartate aminotransferase activity34. It also regulated the relative abundances of the intestinal flora. However, in some special cases (such as an imbalance of intestinal flora caused by antibiotics), the abundance of symbiotic bacteria that degrade polysaccharides decreases and this promotes the production of free SA by increasing sialidase activity, resulting in the proliferation and increased virulence of a large number of opportunistic bacteria in the gut (such as E. coli). This further promotes mucosal layer degradation and intestinal barrier breakdown93. These results not only demonstrate the close relationship between SA, the gut microbiota, and host health but also emphasize that the effects of SA are influenced by the ecological environment of the gut.

The diversity of glycans in complex multicellular organisms is driven by endogenous and exogenous evolutionary selection. Interactions with cells within the body may affect host health. SAs, such as Neu5Ac and Neu5Gc, can be transported to the Golgi, where they can be used as donors of newly synthesized glycoproteins and glycolipids to be delivered to the cell surface as part of the glycosylation of the cell surface of gut microbes94. These glycoconjugates play important roles in a wide range of cell-cell and cell-molecule recognition processes95,96. SA can serve as a surface decoration or attachment site for human pathogens, enabling microbial sialylation to evade the immune system97,98,99. The influence of SA on microorganisms is manifested through its involvement in formatting bacterial surface capsules. Some studies have shown that Neu5Ac can be incorporated as a terminal non-reducing sugar into lipooligosaccharides, which are the main components of the outer membrane of Haemophilus influenzae, and may play important roles in microbial virulence and pathogenicity100.

Based on the findings of previous studies, the acquisition of SA by bacteria depends on several main pathways, including de novo biosynthesis and environmental sources73,97. Neu5Ac aldolase (NanA) and NeuAc synthetase (NeuB) are important enzymes involved in Neu5Ac synthesis. NeuB then catalyzes the condensation of ManNAc 2 with phosphoenolpyruvate to form SA101. NanA catalyzes the production of Neu5Ac from ManNAc and pyruvate102. These results suggest that the ability of microorganisms to synthesize SA de novo is due to specific genes possessed by the microorganisms themselves, and also the influence of SA on microbial physiological functions, such as colonization ability103. Bacteria have evolved multiple ways to obtain SA from the environment73,97. Many bacteria produce sialidases, which remove SA residues from complex glycan structures. Normally, SA levels in the gastrointestinal tract are extremely low. However, the free SA content in the environment may be increased by intestinal dysbiosis or mucosal inflammation, due to increased expression levels of associated sialidases. For example, the human pathogen H. influenzae uses lipopolysaccharide sialylation to evade the host’s innate immune response. However, H. influenzae lacks the gene for the de novo synthesis of SA; therefore, it uses exogenous SA to modify lipopolysaccharides and relies on their respective transporters to protect lipopolysaccharide sialation100,104,105,106.

Besides, host-derived SA influences the viability and virulence of pathogenic microorganisms under certain circumstances. SA can be released by sialidases and then taken up by certain bacteria and used to decorate their surfaces or by microorganisms as a source of nutrients. For example, the results of in vitro and in vivo experiments have shown that free SA induces the expression of neuraminidase genes and toxicity regulators, and enhances the colonization and invasion capacity of Streptococcus pneumoniae in the nasopharynx107. This result suggests that SA is a signaling factor that may lead to fundamental changes in the physiological characteristics of bacteria, thereby enhancing their ability to attach to surfaces and/or survive in biofilm environments. Therefore, it is possible to target host SA, and the virus-binding region to resist viral infection.

Other functions

Serum SA levels are elevated in patients with hypothyroidism, and there is a correlation between SA levels and atherosclerotic indicators108. A significant association has been observed between elevated plasma Neu5Ac levels and an increased risk of poor clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure109. Total serum SA levels in renal dialysis patients are closely correlated with C-reactive protein levels110. There is a correlation between serum SA levels, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels, and blood pressure in patients with prehypertension111. Based on the findings of the abovementioned studies, SA may be a superior marker to C-reactive protein for assessing the occurrence and development of many diseases; however, direct evidence is still lacking. Presently, serum SA levels of patients with different diseases are mostly determined for common types of SA (such as total SA or Neu5Ac), but few studies have explored the relationship between the levels of other types of SA and diseases. Importantly, different SAs play different roles in various physiological environments.

Many questions remain regarding the link between Neu5Gc and host health and disease. Accumulating evidence suggests that excess Neu5Gc intake is closely associated with the occurrence of tumors and other diseases. Paradoxically, the absence of Neu5Gc has adverse health effects. Loss of Neu5Gc synthesis in CMAH-deficient mice is associated with delayed wound healing and age-dependent hearing loss4. These results suggest that adequate Neu5Gc levels play an important role in maintaining physiological health, whereas excessive intake of Neu5Gc may pose health risks.

Dietary SA supplementation, safety evaluation, and application prospects

Neu5Ac mainly exerts protective effects on brain health and metabolic diseases. Further experiments have reinforced the great potential of Neu5Ac, but not Neu5Gc or KDN, in developing functional products. Thus, it is important to determine whether long-term high-dose SA intake has negative effects on the body. Notably, the existing research mainly focuses on animal experiments, and few studies have examined its effects on humans. For example, Choi et al. conducted a subchronic dietary toxicity study of Neu5Ac in Sprague-Dawley rats before the intrauterine stage to assess the in vivo genotoxicity and mutagenicity of Neu5Ac112. The results showed that when the maternal diet contained 2% Neu5Ac, no maternal toxicity or adverse effects on offspring development were observed. In vitro, genotoxicity and mutagenicity tests have also supported the notion that SA is non-genotoxic. These results support the use of Neu5Ac in infant formulas and related foods. Besides, red-meat/Neu5Gc-mediated increased risk for atherosclerosis, which can be mitigated by a diet rich in Neu5Ac113 in the human-like Cmah-null background. However, unlike humans, who cannot synthesize Neu5Gc, Sprague-Dawley rats can synthesize SA, and both Neu5Ac and Neu5Gc in the organs are significantly increased shortly after birth, indicating that individual experimental animals do not fully mimic the physiological characteristics of the human body114. The safety evaluation of SA needs to be further clarified in clinical studies. Therefore, further clinical studies are warranted to evaluate the safety of Neu5Ac as a food additive. However, there are currently no safety evaluation results for Neu5Gc or KDN.

Considering the great potential of SA in maintaining host health, it has been used in drug development. For example, Neu5Ac has been used to synthesize several antiviral drugs, such as zanamivir, which has been recognized as effective in treating and preventing infections, it can be used to prevent and treat the infections of both influenza types A and B115, leading to increased global demand for Neu5Ac. Notably, SA content has also been used as an important indicator of pathology and as a target for intervention notably in cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and malignancy116, given the close association of SA content with individuals in different diseases. A 32 month cohort study found that serum total SA was independently associated with hs-CRP, lipoprotein, intima-media wall thickness, and wall-to-lumen ratio in hemodialysis patients. Increased serum total SA concentrations were associated with more CV events66. To sum up, SA has shown a relatively huge application prospect in the field of food and medicine.

The European Commission approved Neu5Ac for use as a food additive in the market at the prescribed amounts. Notably, in food such as edible bird’s nest, egg yolk peptide, CGMP, etc., SA mainly contains conjugate structure rather than monomer. Approximately 14%–33% of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) are cross-linked with Neu5Ac. For example, 3′-sialyllactose (3′-SL) and 6′-sialyllactose (6′-SL), two simplest sialylated HMOs, incorporate Neu5Ac residue with galactose molecules of lactose via α2,6- and α2,3-linkages, respectively117.

Future prospects

Different SAs show variable effects on host health, and previous studies have mainly focused on Neu5Ac, Neu5Gc, and KDN. Based on previous reports, Neu5Ac has great application prospects owing to its significant probiotic functions. However, some issues remain unaddressed. First, although a large number of preclinical studies have demonstrated the probiotic roles of Neu5Ac, there is a lack of sufficient clinical and safety evaluation data to support this viewpoint. Therefore, it is necessary to strengthen data regarding the application and safety of Neu5Ac in larger clinical samples. In addition, attention should be paid to the addition ratio of Neu5Ac in food (such as infant formula), so that the content and proportion of milk powder are more similar to the composition of breast milk. Second, the requirements for and types of SA vary at different growth stages. Therefore, a safe dosage of Neu5Ac for different individuals and the appropriate age groups should be determined. An excess and/or lack of SA can have adverse effects on host development. Third, the function of different types of SA is affected by the external environment, such as the physiological state of the host (health or disease), which may cause changes in the way SA is absorbed, metabolized, and transported by the body, resulting in different physiological effects. Further analysis is needed to determine the pathways by which different types of SA are absorbed and transported to healthy and diseased tissues to develop appropriate treatments that target SA regulation.

Notably, at present, multi-omics (especially glycomics) and other technologies can be used to quantitatively detect changes in the content of different SAs and their related synthetic precursors. Combined with data from human physiological and biochemical index databases, artificial intelligence, and other technologies to assess the regulation of SA content in the host, a more accurate SA supplement type and dose can be formulated for the test population.

Responses