The puzzle of biologics manufacturing platform patents

Background and proposals for reform

As noted, contrary to standard patent law, some companies may seek and obtain patents either that embody processes that the company is already using secretly or that change these processes only modestly. The most direct reason is that the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) does not appear to receive information on an applicant company’s existing processes. (Below we confirm this supposition empirically.) Only the FDA, which must approve all biologics for marketing, receives this information as a matter of course.

Recognizing the information gap, a July 2021 White House Executive Order urged the USPTO and FDA to improve inter-agency information flow and thus patent quality and competition9. However, USPTO guidance issued on 29 July 2022 puts the onus on time-constrained patent examiners to ask applicants about secret manufacturing process information submitted to the FDA10. For this reason, and because of high-profile cases showing firms making conflicting statements to the USPTO and FDA11, the proposed Interagency Patent Coordination and Improvement Act of 2023 (IPCIA) sets up a detailed structure for direct inter-agency information flow, including with respect to secret information.

In addition to potentially invalid patents, would-be biosimilar entrants face substantial challenges with respect to notice. Although many originator biologics patents are filed after FDA approval of a relevant biologic, under the BPCIA, biosimilar companies must await litigation before they know which patents an originator biologic firm may assert12. Manufacturing platform patents create additional notice problems13 — by definition, these patents do not specify any particular originator molecule.

A final challenge pertains to the intersection of validity and notice. In some cases, a manufacturing platform patent may be valid because it encompasses a novel and non-obvious improvement over the process that was used at launch of the reference product. Such non-obvious improvements to platforms should be encouraged, particularly if the platform is going to be used across many subsequent product introductions. The problem is that, under the current system, a biosimilar company faced with such a patent cannot know whether the patent is novel and non-obvious and that it should therefore be able to make the previous biologic without infringing.

Consider a simplified hypothetical example of a company with two FDA-approved biologics and one platform patent. Biologic 1 is approved at time 1 and biologic 2 at time 2. Meanwhile, the company’s platform patent has a priority filing date halfway between — say, time 1.5. Assuming the platform patent represented a non-obvious improvement over the process used at time 1, and was used to make biologic 2, asserting the patent against a biosimilar of biologic 2 would create no notice challenge. And if the company making biosimilar 1 decided to use the improvement because (for example) the improvement was more efficient, patent assertion would be appropriate. The notice problem would arise in the case of the biosimilar company that simply wanted to follow the old process but could not be sure whether the old process was covered by an invalid patent. Meanwhile, the risk of an invalid patent to the old process of manufacturing biosimilar 1 follows directly from the problems of incomplete information at the USPTO about secret manufacturing processes, of time-constrained patent examiners who must parse that information, and of conflicting statements made to the USPTO and FDA.

Or consider another hypothetical example, where an originator develops several mutually non-obvious platform processes (Processes 1–10) before manufacturing a biologic. It chooses one process to use; say, Process 10. Well after launch, it files for patents on all ten processes. A biosimilar company, faced with patents that ‘flood the zone,’ may either eschew the market entirely or pick one on the logic that it was used and therefore invalid. But only the patent on Process 10 is invalid; all others would be valid, and so the biosimilar would face a 90% chance of infringement; the invalid notice is buried among valid patent notices with no guidance to potential competitors. The costs caused by this lack of notice could clearly be substantial.

While the IPCIA attempts to address potential invalidity issues before they occur, other proposed legislation targets notice and nonuse issues after the fact. In July 2024, the US Senate passed the Cornyn–Blumenthal Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act, which caps at 20 the number of secondary patents that may be asserted by an originator against a biosimilar of a given reference product. In order to be subject to the cap’s restrictions, these patents either must be filed late (actual filing date more than 4 years after a given biologic’s approval) or must cover a manufacturing process that is not used by the originator to make the reference product.

The issue of platform patents is also timely given the Prevent Pandemics Act’s effort to promote technology that “facilitates the manufacture or development of more than one drug or biological product through a standardized production or manufacturing process.”8 As directed by Congress, the FDA issued guidance in May 2024 discussing biopharma companies’ requests for “platform technology designation.” As the guidance notes, benefits of receiving this designation include timely advice and engagement with the FDA, as well as the ability to leverage data from a previous product that used the technology14.

While the guidance does not discuss patent issues, attention to such issues is important. As a vast literature investigating patents on digital platform standards demonstrates, companies that own patent portfolios that cover platform technologies can use them to substantially enhance their market power15. This flurry of policy interest informs our research methods.

Methods

We define manufacturing process patents to encompass patents containing at least one claim to (i) the preparation and production of the master cell line containing the gene for the desired protein; (ii) large-scale growing of cells that produce the protein, along with any tool designed for that purpose; and (iii) isolation, purification, analysis and post-production modification of the protein to make it ready for therapeutic use. We also include claims drawn to methods for producing engineered proteins and formulations.

As noted, we focus on patents with platform claims applicable to more than one biological product. Our definition of a platform claim parallels that found in the Prevent Pandemics Act. We examine patents issued to eight of IQVIA’s top ten biologics manufacturers by 2022 US sales. These are AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Genentech, Janssen (Johnson & Johnson), Merck, Novartis and Sanofi. We excluded Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk (the other companies in the IQVIA top ten) from our analysis because of unique issues related to their historical dominance in the insulin market and their current dominance in the GLP-1 agonist market. We added Regeneron, a prominent biologics company just outside the top 10 that has recently become quite active in litigation against biosimilars.

Unlike patents that specify a particular molecule, which can be retrieved by searching for information on that molecule, platform patents must be found by casting a wide net for different manufacturing steps and then sifting through results to eliminate false positives. To cast a wide net, we began by modifying a series of queries initially provided by the consulting firm Evalueserve. A high-level summary of our modified queries can be found in the Supplementary Data, Appendix A.

We implemented these queries in the Lens platform (https://www.lens.org/). Search results were then filtered by date range (dates of actual filing 2004–2024), jurisdiction (United States), document type (issued and amended patents) and assignees or applicants from each of the selected companies. Because of lags associated with patent grant, our filing dates conclude in 2022.

We used FACTSET to find, and include, most parent and subsidiary companies. For AbbVie and Genentech, however, we included their parent companies (Abbott Laboratories and Roche Group, respectively) only when these were co-assignees or co-applicants on the patent; both Abbott and Roche have vast operations outside the biologics arena. We also included only subsidiaries that appeared to be contributing to the selected company’s biologics products.

As this first collection was still too large to process manually, we performed an internal keyword search to exclude irrelevant patents, such as methods of treatment, gene or cell therapy, diagnostics, vaccines, and plant- or cosmetics-related patents. Details of this internal keyword search, and of further manual data curation, can be found in Supplementary Data, Appendix A.

Our review indicated that, although our search queries had been targeted toward patents with platform claims, we also retrieved a number of patents with claims specific to a particular biologic. Our final manufacturing patent dataset comprises 653 platform patents and 336 biologic-specific patents. Further details of our final dataset are in Supplementary Data, Appendix A. The full dataset is available for noncommercial use on request. Various robustness checks are detailed in Supplementary Data, Appendix B.

To gather data on the prosecution of manufacturing platform patents, we uploaded our collection into the LexisNexis Patent Advisor database and performed various keyword searches to determine whether patent examiners asked about prior commercial use of the manufacturing process. Information regarding the keyword search and of our manual analysis of 140 non-final and/or 102 final and/or 103 rejection reports are found in Supplementary Data, Appendix C.

To assemble litigation data on the patents in our set, we used Docket Navigator, data on biologics litigation16, and the FDA Purple Book’s ‘3A list.’ Starting in 2021, originators have been required to submit to the 3A list patents they believe are infringed by biosimilar defendants, even if the originators ultimately never assert them. Details of this litigation collection are found in Supplementary Data, Appendix D. Finally, we obtained information on all approved originator biologics from the FDA’s public resources.

Key results

For each of the nine companies, Table 1 shows the number of FDA-approved originator biologics between 2004 and 2022, as well as the number of platform patent applications filed by the company during that time (by actual filing date — that is, the date on which the patent was actually filed even if it can by virtue of various legal doctrines claim priority to an earlier patent date) that eventually issued as patents. The ratio of platform patents to approvals is interesting in light of the regulatory hurdles to substantial process change once a product is approved. Given these hurdles, large accumulations of patents on manufacturing processes without a series of approved products over time suggest that the company may not be using some substantial portion of the patents in most (or any) of its biologics production.

Companies that started out producing entirely or mostly recombinant biologics (that is, Regeneron, Genentech and Amgen) have the largest number of manufacturing process platform patents (Table 1). Companies with a greater focus on small molecule assets have fewer such patents. The exception is Merck, which has a substantial number of patents despite a history as a small molecule company. One reason may be that Merck obtained its first recombinant biologic approval in 1986 while the other companies with small molecule origins did so later (Janssen in 1994, Novartis in 1998, AbbVie in 2002 and BMS in 2005).

That said, for Amgen and Genentech, their ratio of platform patents to approved biologics is more modest. In principle, these companies, along with other companies with many approvals, have the potential to actually use platform patents in a standardized fashion across these approvals. In contrast, for Merck and AbbVie, their modest biologics approval record suggests an effort to accumulate platform patents that may not be used but that are nonetheless collected, at least in part, to chill biosimilar entry.

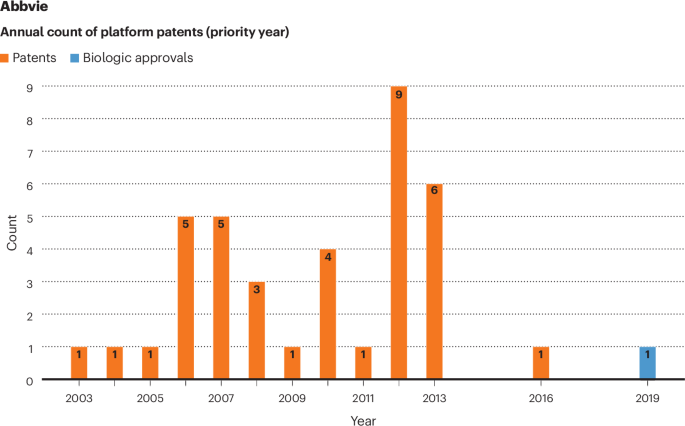

The contrast between different companies’ platform patenting strategies is also demonstrated by more granular analysis of priority filing years and FDA approval. Thirty-seven of AbbVie’s 38 platform patents have priority filing dates between 2004 and 2016 — a period during it had no new FDA approvals of recombinant biologics (Fig. 1). Although these patents either are invalid or were not used to make a biologic at launch, 8 of the 37 were nonetheless involved in litigation against would-be biosimilar competitors of Humira (adalimumab), which was approved and launched in 2002, more than one year before this time frame (Supplementary Data, Appendix D, Supplementary Table 3).

Thirty-seven of AbbVie’s 38 platform patents have priority filing dates between 2004 and 2016 — a period during which it had no new FDA approvals of recombinant biologics.

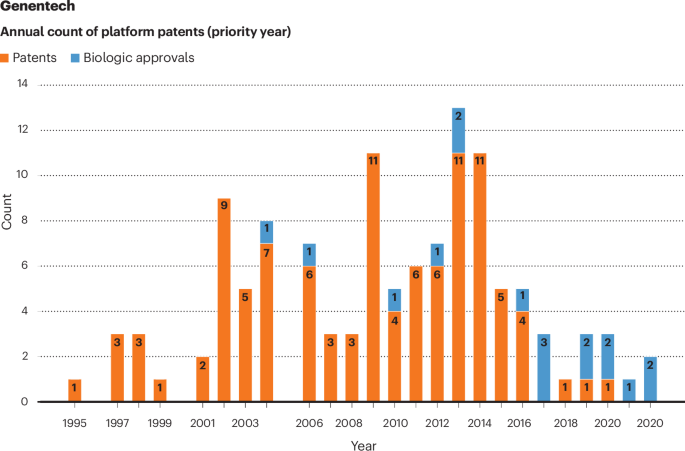

The Genentech case poses an interesting contrast. Genentech had 7 biologics approved (and an unknown number of platform patents granted) before our study period. During our study period, it enjoyed a steady stream of FDA approvals, starting with Avastin (bevacizumab) in 2004 (Fig. 2). Genentech has also accumulated 73 platform patents that have priority dates after Avastin’s approval. Some of those patents may be valid, used as part of a process that is becoming standardized to promote efficiency and quality, and quite properly asserted against biosimilars of some of the 16 subsequent Genentech biologics.

Genentech has accumulated 73 platform patents that have priority dates since 2004.

That said, as of June 2024 (Supplementary Data, Appendix D, Supplementary Table 3), a number of these patents have been asserted numerous times not simply to protect subsequent biologics (for example, Actemra, approved in 2010) but also against biosimilars of Avastin, Rituxan (rituximab, approved 1997) and Herceptin (trastuzumab, approved 1998). For example, the Genentech patents in Table 2 have been asserted not only against biosimilars of Actemra (tocilizumab) but also against biosimilars of Rituxan, Herceptin and Avastin (RHA). With respect to RHA, the patents are either invalid or were not used at approval. Even for Actemra, patent 9714293 is either invalid or was not used at approval.

In Supplementary Data, Appendix E, we provide histograms of priority filing dates, actual filing dates and FDA approvals for all nine companies in our dataset. A comparison of these histograms with our litigation data (Supplementary Data, Appendix D, Supplementary Table 4) reveals some interesting patterns. Like Genentech, Amgen appears to be deploying its large portfolio of platform patents and FDA approvals to protect both previous approvals and subsequent approvals. Meanwhile, Regeneron’s large portfolio of platform patents is currently being asserted only against biosimilars of Eylea, the only one of its biologics currently facing biosimilar entry. Presumably Regeneron’s incidence of patent assertion will increase going forward. Yet even the patents currently being asserted have priority dates both before and after Eylea’s approval date.

Ex ante USPTO examination is necessary to provide would-be biosimilar companies assurance that the platform patents are in fact valid over prior art created by a company’s prior commercial production. To determine whether the USPTO considered the possibility of prior commercial use, we used Patent Advisor to search patent prosecution histories (specifically Section 102 and 103 rejections) for terms related to such use. We did not find a single case in which the prosecution history indicated an inquiry into companies’ existing manufacturing processes. Without evidence of such inquiry, we cannot be confident that even companies like Genentech, with their impressive records of FDA approval, have platform patents that are valid.

We also examined the impact of potential limits on ex post assertion, for example, the Cornyn–Blumenthal 20-patent cap on assertion of certain secondary patents that are either filed 4 years after FDA approval or not used. Although courts are given discretion not to enforce the cap, and secrecy prevents us from determining whether a given manufacturing process patent has been used — as, indeed, such a determination would be difficult for a biosimilar applicant — we can determine whether consistent judicial adherence to the 4-year post-approval cap could exert a constraining effect.

To do this, we looked at biologics that have recently come out of their 12-year ‘absolute’ regulatory exclusivity zone — that is, those that were FDA-approved in the period 2009–2012. Previous research on patents specific to the six top-selling biologics showed that the density of patent filing (by actual filing date) peaks at 12 years after approval2.

Results are shown in Table 3. The numbers for companies such as Amgen, Genentech and Regeneron are substantial; the cap would limit the assertion of many platform patents for these companies and would limit the assertion of at least some platform patents for half of the ten biologics in this set.

Policy implications

Several policy implications emerge from our results. First, given the complete absence of patent examiner inquiry into prior commercial use, the IPCIA’s provision for direct, trade-secrecy-preserving information exchange between the FDA and the USPTO is necessary. However, the bill’s current requirement for pre-exchange consultation with product sponsors imposes expensive burdens on time-constrained agency personnel and should be excised. Second, although the Cornyn–Blumenthal cap on assertion of patents that are filed late or that are not used should exert some constraining effect, the effect would be strengthened by eliminating judicial discretion and by creating mechanisms by which a biosimilar could determine whether or not a patent had been used).

Finally, the recent creation of a ‘platform technology designation’ could yield not only private benefits for originators but also social benefits in the form of greater efficiency and quality17. To the extent that the platform technology is covered by many patents, however, the designation reinforces the exclusionary power of such patents. By definition, the technology then becomes one that biosimilar competitors must use not just in one product but across multiple originator products.

To mitigate the possibility of inappropriate anticompetitive use, companies that receive the benefit of a platform technology designation should be required in return to introduce greater transparency in the patent ecosystem. Specifically, they should be required both to identify which of their products use the platform and to list patents that cover the platform. Such a listing requirement would still fall short of what is required for small molecule patents in the Orange Book. But it would at least begin to account for the particularly potent anticompetitive potential of a patent on a FDA-designated platform.

Responses