The role of Neuregulin-1 in steatotic and non-steatotic liver transplantation from donors after cardiocirculatory death

Introduction

The shortage of liver donors means clinical liver transplantation (LT) waiting lists increase, so it is desirable to include “extended criteria” donors1, including donors after cardiocirculatory death (DCDs) or with steatosis (DCDs)2. However, these grafts show increased ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury with the subsequent increased risk of early graft dysfunction and primary graft non-function3,4,5. Many steatotic livers, particularly with severe fatty infiltration, are not considered for LT. So, increasing steatosis prevalence means the donor shortage is becoming critical6. Advances in therapies that reduce LT risks associated with steatotic livers and DCDs are urgently needed to decrease waiting lists.

Experimental cardiac abnormalities studies indicate that Neuregulin-1 (NRG1), an important type of epidermal growth factor-like protein, is altered in plasma7,8,9. So, cardiocirculatory death (CD) may cause systemic and subsequent hepatic NRG1 deficiencies with negative effects in DCD LT, as liver is an important NRG1 target10. Moreover, NRG1 has diverse effects on hepatocytes. Its beneficial effects include ErbB3-AKT activation, and IL-6 and TNF-α inhibition, in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease11. Moreover, NRG1 offers direct cryoprotection against toxicity from pentachlorophenol in isolated hepatocytes and furthermore reduced both inflammation and expression of stress-related genes12.

NRG1 helps regulate p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1)13,14. PAK1 seems to inhibit death for in vitro beta cells and human cancer cell lines15,16. Over-expression of PAK1 is beneficial against inflammatory bowel diseases17. Recently it was demonstrated that PAK1 plays a role in the beneficial effects of NRG1 in LT from brain death donors (BDD)18. To our knowledge, no study has previously evaluated the potential benefits of the NRG1-PAK1 pathway in LT from DCDs. In addition to the above, it has been reported that PAK1 acts through regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA)19. In different cell lines, PAK1 and VEGFA expression is positively regulated by NRG120,21. On the other hand, VEGFA is reportedly beneficial in non-steatotic livers in various surgery scenarios, including warm ischemia, liver resection and BDD LT18,22. So, the relationship between NRG1, PAK1 and VEGFA could be extremely important in DCD LT.

Insulin growth factor 1 (IGF1) could also be involved in the mechanisms of action of NRG1. In this sense, NRG1 and IGF1 interact in cardiomyocyte23; in endothelial cell cultures, PAK1 and IGF1 are related24. Furthermore, IGF1 protects against hepatic I/R injury: recombinant IGF1 treatment reduces hepatic injury in normothermic ischemia25 and improves LT outcomes26. So, like VEGFA, this growth factor could be involved in the NRG1 effects and underlying signaling mechanisms in LT from DCD.

Therefore, we evaluate: (a) the role of NRG1 in LT of both non-steatotic and steatotic liver recovered from DCDs; (b) the involvement of PAK1 in signaling pathways underlying NRG1 effects in this pathology; and (c) whether NRG1-PAK1 signaling pathway can regulate VEGFA and/or IGF1 in non-steatotic and steatotic LT from DCDs. Potential differences in such signaling pathways between non-steatotic and non-steatotic livers should be not discarded. This is because the underlying pathogenic mechanisms sensitivity are probably very different since one involves warm ischemia direct injury (here 30 min of cardiac arrest), the other intrinsec functional pathways alteration through fat accumulation in hepatocytes. The results of this study therefore could help characterize pathological molecular signaling mechanisms in both non-steatotic and steatotic livers in LT from DCDs. This, in turn, would result in identifying therapeutic targets to potentially improve post-LT outcomes in liver grafts recovered from DCDs.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals

This study was performed using male lean and obese Sprague Dawley rats (400-450 g) as nutritional obesity experimental model. Obese rats fed with a high fat diet (D12451, 45% kcal fat; Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) for 10 weeks whereas Ln rats fed with a control diet (2014 Teklad global, 13% kcal fat; Envigo, Huntingdon, UK)27,28. Ob rats showed severe macrovesicular and microvesicular fatty infiltration in hepatocytes (60–70% steatosis); Ln rats, no steatosis. Procedures were conducted according to EU regulations (Directive 86/609/EEC).

Experimental design

The animals were randomly distributed into the following groups:

Protocol 1. To investigate the role of NRG1 and VEGFA and their potential relationship

Group 1. Sham (n = 12: rats: 6 Ob and 6 Ln): only subjected to anesthesia and laparotomy.

Group 2. Prior to LT (n = 12 rats: 6 Ob and 6 Ln): Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, then the livers were flushed with University of Wisconsin (UW) solution, isolated, and maintained in cold ischemia in UW solution for 4 hours.

Group 3. Prior to CD + LT (n = 12 rats: 6 Ob and 6 Ln): Rats were anesthetized with isoflurane. CD was then induced via hypoxia by performing an incision in the diaphragm and blocking the descending aorta. An in situ 30-minutes period of warm ischemia was then applied17. After, livers were flushed with UW solution, isolated, and maintained in cold ischemia in UW solution for 4 hours.

Group 4. LT (n = 24 rats). In subgroup 4.1 (n = 12 rats: 6 LTs with steatotic grafts, from 6 Ob donors to 6 Ln recipients), the Ob rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, and their steatotic livers were then flushed with UW solution, isolated, preserved in ice-cold UW solution for 4 hours, and implanted into the Ln rats. In subgroup 4.2 (n = 12 rats: 6 LTs with non-steatotic grafts, from 6 Ln donors to 6 Ln recipients), the same surgical procedure was applied, but with Ln rats as both donors and recipients18,19.

Group 5. CD + LT (n = 24 rats). In subgroup 5.1 (n = 12 rats: 6 LTs with steatotic grafts, from 6 Ob donors to 6 Ln recipients), the Ob rats were anesthetized with isoflurane. CD was then induced via hypoxia by performing an incision in the diaphragm and blocking the descending aorta. An in situ 30-minutes period of warm ischemia was then applied17. After, livers were flushed using UW solution, isolated, preserved in ice-cold UW solution for 4 hours, and implanted into the Ln rats18,19. In subgroup 5.2 (n = 12 rats, 6 LTs with non-steatotic grafts, from 6 Ln donors to 6 Ln recipients), the same CD surgical procedure and LT were applied, but with Ln rats as both donors and recipients.

Group 6. CD + LT+anti-NRG1 (n = 24 rats). As Group 5, but with administration of an antibody against NRG1 (10 mg/kg, i.v.)20,21 immediately after reperfusion in the recipient.

Group 7. CD + LT+anti-NRG1 + VEGFA (n = 24 rats). As Group 5, but with administration of an antibody against NRG1 (10 mg/kg, i.v.)20,21 and VEGFA (10 mg/kg, i.v.)22,23 immediately after reperfusion in the recipient.

Group 8. CD + LT + NRG1. This group was divided into two subgroups. Subgroup 8.1, CD + NRG1(a)+LT (n = 24 rats): as Group 5, but treated with 5 mg/kg, i.v. NRG124 immediately after reperfusion in the recipient. Subgroup 8.2, CD + NRG1(b)+LT (n = 24 rats): as Group 5, but treated with 10 mg/kg, i.v. NRG124 immediately after reperfusion in the recipient.

Group 9. CD + LT + VEGFA (n = 24 rats). As Group 5, but with administration of VEGFA (10 mg/kg, i.v.)22,23 immediately after reperfusion in the recipient.

Group 10. CD + LT(b) (n = 40 rats). In subgroup 5.1 (n = 20 rats: 10 LTs with steatotic grafts, from 10 Ob donors to 10 Ln recipients), the Ob rats were anesthetized with isoflurane. CD was then induced via hypoxia by performing an incision in the diaphragm and blocking the descending aorta. An in situ 30-minutes period of warm ischemia was then applied17. After, livers were flushed using UW solution, isolated, preserved in ice-cold UW solution for 24 hours, and implanted into the Ln rats18,19. In subgroup 5.2 (n = 20 rats, 10 LTs with non-steatotic grafts, from 10 Ln donors to 6 Ln recipients), the same CD surgical procedure and LT were applied, but with Ln rats as both donors and recipients.

Group 11. CD + LT(b)+anti-NRG1 (n = 40 rats). As Group 10, but with administration of an antibody against NRG1 (10 mg/kg, i.v.)20,21 immediately after reperfusion in the recipient.

Group 12. CD + LT(b)+VEGFA (n = 40 rats). As Group 10, but with administration of VEGFA (10 mg/kg, i.v.)22,23 immediately after reperfusion in the recipient.

Protocol 2. To evaluate the role of adipose tissue and the involvement of circulating sFlt1 in the levels of NRG1 and VEGFA in recipients with either steatotic or non-steatotic liver grafts.

Group 13. CD + LT + LP (n = 24 rats). As Group 5, but peripheral adipose tissue (mesenteric, perirenal, retroperitoneal, and epididymal) were resected and extracted from the recipient before graft implantation25.

Group 14. CD + LT+anti-sFlt1 (n = 24 rats). As Group 5, but with an antibody against soluble VEGF receptor-1 (sVEGFR1; also known as sFlt1) (1 mg/kg i.v.) immediately after reperfusion in the recipient26.

Group 15. CD + LT + VEGFA+anti-sFlt1 (n = 24 rats). As Group 5, but with VEGFA (10 mg/kg, i.v.)6,7 and an antibody against soluble VEGF receptor-1 (sVEGFR1; also known as sFlt1) (1 mg/kg i.v.) immediately after reperfusion in the recipient26.

Group 16. CD + LT + LP + NRG1(b) (n = 24 rats). As Group 5, but mesenteric, perirenal, retroperitoneal, and epididymal adipose tissue were resected and extracted from the recipient before graft implantation, and treated with 10 mg/kg, i.v. NRG124 immediately after reperfusion in the recipient.

Samples were collected after cold ischemia in Groups 2 and 3. In Groups 4-9 and 13-15, samples were collected 6 hours after LT. We selected these study conditions, including the doses and pre-treatment points used with the different drugs, based on studies cited together with our preliminary studies. A 4-hour period of cold ischemia is long enough to induce liver injury after transplantation in both types of liver graft, while at the same time resulting in high 6-hour survival rates after LT. Thus, the experimental conditions used in this study were the most appropriate to evaluate the effect of NRG1 on injury and inflammation, as well as the NRG1 signaling pathways, in LT of grafts from both non-steatotic and steatotic livers from DCDs. In addition, to evaluate the effect of different drugs (anti-NRG1 and VEGFA treatment) on prolonged ischemic period (24 hours), after the surgical procedure, the survival of receptors was monitored for 14 days in Groups 10, 11 and 12

The experimental groups are summarized in Fig. 1.

Protocol 1. Group 1. Sham (anesthesia and laparotomy). Group 2. Prior to LT (Livers maintained in cold ischemia in UW solution for 4 h. Group 3. Prior to CD + LT (After CD induction, livers were maintained in cold ischemia in UW for 4 h. Group 4. LT (4.1 steatotic grafts from Ob rat preserved in UW for 4 h and implanted into Ln rats. 4.2 the same surgical procedure was applied, but with Ln rats as both the donors and recipients). Group 5. CD + LT (5.1 CD was induced in Ob rats. Then, livers were preserved in UW for 4 h and implanted into Ln rats. 5.2 the same as 5.1, but with Ln rats as both the donors and recipients). Group 6. CD + LT+anti-NRG1 (as Group 5 + NRG1 antibody). Group 7. CD + LT+anti-NRG1 + VEGFA (As Group 5 + NRG1 antibody and VEGFA). Group 8. CD + LT + NRG1 (As Group 5 + different doses of NRG1; NRG1(a), 5 mg/kg and NRG1(b), 10 mg/kg). Group 9. CD + LT + VEGFA (as Group 5 + VEGFA). Group 10. CD + LT(b) (as Group 5 but livers were preserved in UW for 24 hours). Group 11. CD + LT(b)+anti-NRG1 (as Group 10 + NRG1 antibody). Group 12 CD + LT(b)+VEGFA (as Group 10 + VEGFA). Protocol 2. Group 13. CD + LT + LP (As Group 5+lipectomy in recipient before liver grafts implantation). Group 14. CD + LT+anti-sFlt1 (As Group 5+sFlt1). Group 15. CD + LT + VEGFA+anti-sFlt1 (As Group 5 + VEGFA and a Flt1 antibody). Group 16. CD + LT + LP + NRG1(b) (As Group 5+lipectomy in recipient before liver graft implantation and NRG1(b)). All drugs were administered immediately after reperfusion in recipient.

Biochemical determinations

Plasma transaminases (alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)) were determined using standard procedures. Total bilirubin, the von Willebrand factor (vWF) and hyaluronic acid (HA) were determined in plasma using commercial immunosorbent assay kits (total bilirubin MBS730053, vWF MBS703460 and HA MBS162865 from MyBioSource Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). NRG1 and VEGFA levels were quantified in liver, plasma and adipose tissue using immunoassay kits (NRG1 E-EL-R0790 and VEGFA E-EL-R2603 96 T from Elabscience Biotechnology Co. Ltd, Wuhan, China) according to manufacturers’ instructions. PAK1, IGF1, PI3K, phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt), Wnt2 and Id1 were measured in liver tissue using immunoassay kits according to manufacturers’ instructions (PAK1 MBS2887909, p-Akt MBS3808116, Wnt2 MBS8807293 and Id1 MBS1604796 from MyBioSource, Inc, San Diego, CA, USA; IGF1 E-EL-R0010 from Elabscience Biotechnology Co. Ltd, Wuhan, China; PI3K CSB-E08418r-96T from Cusabio, Wuhan, China). sFlt1 in plasma was measured using a commercial kit (sFlt1 MBS732055 sandwich from MyBioSource, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). ILs (IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10) were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays with commercial kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). Lipid peroxidation was determined by measuring the formation of malondialdehyde (MDA) with the thiobarbiturate reaction27. As an index of neutrophil accumulation, myeloperoxidase (MPO) was measured photometrically with 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine as the substrate28. To establish hepatic edema, after resection, hepatic samples were weighed and placed in a drying oven at 55°C to constant weight. Here, hepatic edema is revealed by an increase in the wet-to-dry weight ratio29. We measured hepatic nitrotyrosine as a peroxynitrite formation index, using a commercial kit (HK501 from Hycult Biotech, Uden, The Netherlands).

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from frozen liver and peripheral adipose tissue using TRIzol Reagent (15596026 from ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and was reverse transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (4368813 from ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed with TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (4352042 from ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and using premade Assays-on-Demand TaqMan probes (Rn01482168_m1 for Nrg1, Rn01511602_m1 for Vegfa and Rn00667869_m1 for actin beta as endogenous control, from ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Histology

To establish the severity of the hepatic injuries, sections of liver embedded in paraffin were stained with H&E. Then, board-certified pathologists determined a blind histological score using a point-counting method: grade 0, minimal or no evidence of injury; grade 1, mild injury consisting of cytoplasmic vacuolation and focal nuclear pyknosis; grade 2, moderate to severe injury with extensive nuclear pyknosis, cytoplasmic hypereosinophilia, and loss of intercellular borders; grade 3, severe necrosis with disintegration of hepatic cords, hemorrhage, and neutrophil infiltration; and grade 4, very severe necrosis with disintegration of hepatic cords, hemorrhaging, and neutrophil infiltration27.

Statistics

The normality of our data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Due to deviations from normality, we utilized the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test to determine the statistical significance of differences among groups. For groups showing significant differences in the Kruskal-Wallis test, we conducted post-hoc pairwise comparisons using the Mann–Whitney U test, with p-values adjusted using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method to control for multiple comparisons. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are expressed as means ± standard error. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and was statistically analyzed with a log rank test and p values of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Role of endogenous NRG1 and its effects on VEGFA in steatotic and non-steatotic LT from DCDs

Non-steatotic and steatotic liver NRG1 levels were similar in Sham (without surgical intervention), Prior to LT (livers with cold ischemia, but without CD) and Prior to CD + LT (DCDs grafts with cold ischemia) (Fig. 2a). Therefore, CD does not increase hepatic NRG1 before grafts implantation in the recipient. However, NRG1 protein levels increased in grafts in CD + LT, compared to LT and Sham (Fig. 2a).

a Levels of NRG1 and PAK1 in liver tissue. b Levels of IGF1 and VEGFA in liver tissue. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

NRG1 helps regulate PAK113,14,18. However, the changes we observed in NRG1 levels in our experimental conditions were not associated with changes in hepatic PAK1 levels (Fig. 2a): PAK1 levels in non-steatotic and steatotic LT from DCDs (DCD + LT) were similar to Sham and LT. Furthermore, administration of an NRG1 antibody to inhibit its action (CD + LT+anti-NRG1), yielded no changes in hepatic PAK1 levels compared to CD + LT (Fig. 2a). So, PAK1 is not regulated by NRG1.

We next investigated the capacity of NRG1 to affect levels of IGF1 and VEGFA in non-steatotic and steatotic LT from DCDs. IGF1 levels in both non-steatotic and steatotic grafts were unchanged in all our groups (Fig. 2b). Similarly to NRG1, VEGFA levels were similar in Sham, Prior to LT (cold ischemia, without CD) and Prior to CD + LT (Fig. 2b), but increased in non-steatotic and steatotic grafts in CD + LT, compared to LT and Sham. Thus, as with NRG1, VEGFA increased in the recipient during reperfusion in both types of liver from DCDs. NRG1 inhibition (CD + LT+anti-NRG1) caused no changes in hepatic IGF1, but decreased VEGFA in both types of liver compared to CD + LT (Fig. 2b).

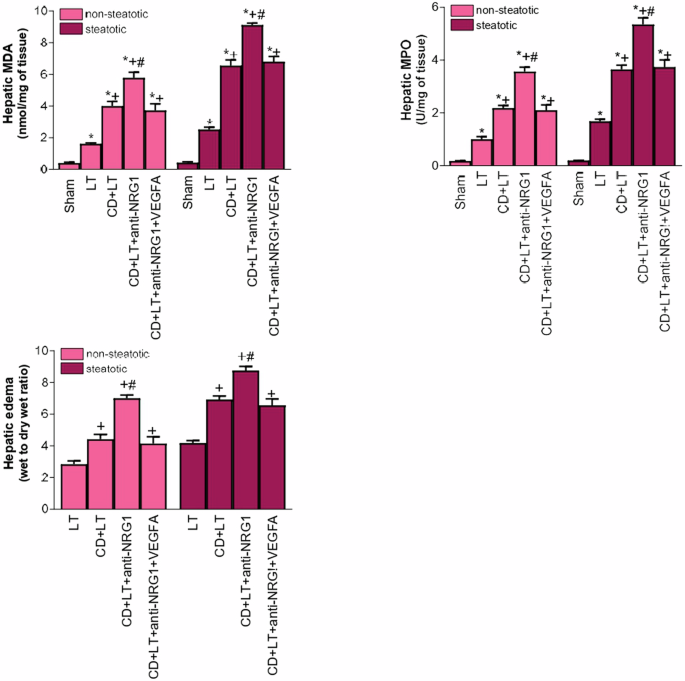

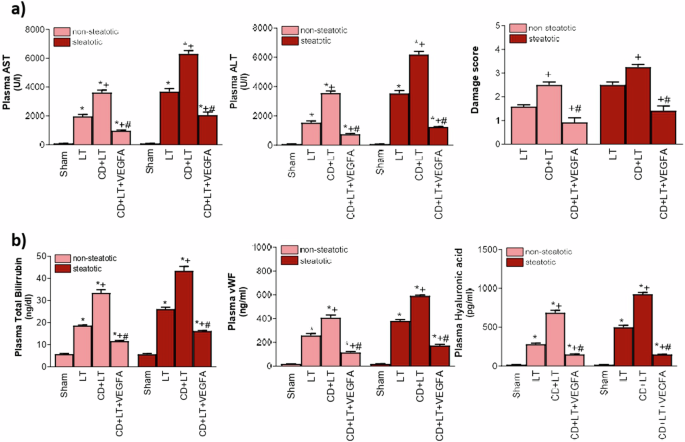

Relevance of NRG1-VEGFA pathway for damage and inflammation in steatotic and non-steatotic LT from DCDs

After this, we addressed the importance of NRG1-VEGFA for hepatic injury in non-steatotic and steatotic LT from DCDs. NRG1 inhibition (CD + LT+anti-NRG1) exacerbated hepatic injury, increasing transaminases, damage scores (Fig. 3a), total bilirubin, and endothelial cell damage (vWF, HA; Fig. 3b), compared to CD + LT, in both liver types. It also increased inflammatory responses: increased oxidative stress (MDA), neutrophil accumulation (MPO), and edema formation in non-steatotic and steatotic grafts, compared to CD + LT (Fig. 4). In CD + LT, histological evaluation of non-steatotic livers showed moderate multifocal areas of coagulative necrosis, while steatotic grafts showed extensive and confluent areas. The extent and number of necrotic areas increased in steatotic and non-steatotic grafts in CD + LT+anti-NRG1 (Fig. 5).

a ALT and AST levels in plasma and damage score in the liver. b total bilirubin levels, vWF, and HA levels in plasma. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

Liver MDA levels as index of oxidative stress; liver MPO levels as neutrophil accumulation and hepatic edema parameter. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

In the CD + LT, histological evaluation of non-steatotic livers showed moderate multifocal areas of coagulative necrosis and neutrophil infiltration, randomly distributed throughout the parenchyma, whereas steatotic livers of the CD + LT group showed extensive and confluent areas of coagulative necrosis. The extent and the number of necrotic areas was increased in steatotic and non-steatotic grafts of the CD + LT+anti-NRG1 group while the extent and the number of necrotic areas was reduced in the CD + LT + VEGFA group (10X).

These increased injuries in CD + LT+anti-NRG1 were associated with decreased VEGFA in non-steatotic and steatotic livers. So, we next studied if endogenous NRG1 exerted its benefits via VEGFA. To do this we had to give a dose of VEGFA to rats (both with non-steatotic and with steatotic livers) undergoing blockade of NRG1 effects (CD + LT+anti-NRG1 + VEGFA group) that resulted in liver VEGFA levels like those registered in the CD + LT group (Fig. 2b). Under these conditions, hepatic injury (transaminases, damage score, total bilirubin, vWF, HA, and damage score; Fig. 3) and inflammation (MDA, MPO, and edema; Fig. 4) were now lower than when only NRG1 was inhibited (CD + LT+anti-NRG1), producing similar results to CD + LT, in non-steatotic and steatotic livers.

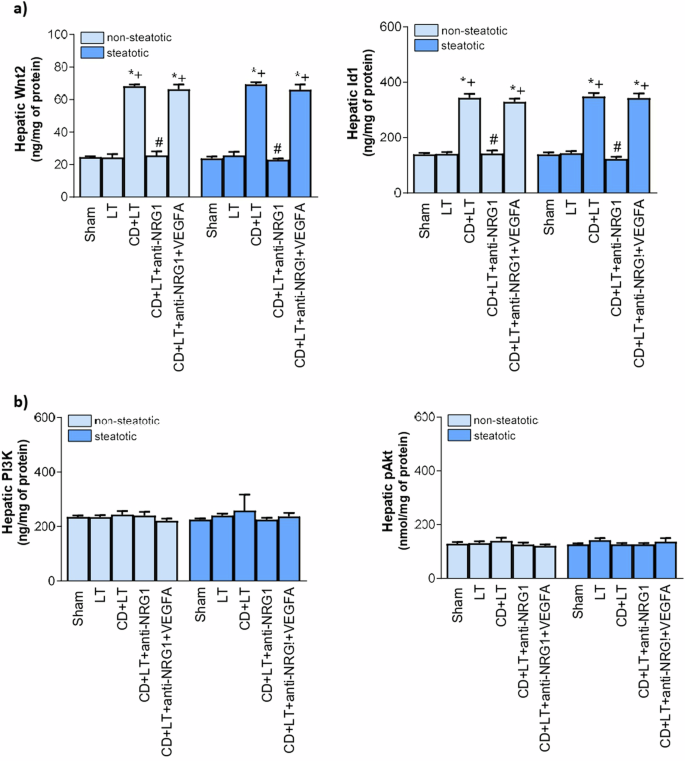

The mechanisms of action of endogenous NRG1-VEGFA pathway in steatotic and non-steatotic LT from DCDs

As VEGFA is downstream of NRG1, next, we investigated whether the effects of VEGFA on hepatic damage and inflammatory response were mediated though the Id1-Wnt2 pathway. Indeed, the relevance of Id1-Wnt2 pathway in damage and inflammation29,30, and relationship between VEGFA and Id1-Wnt222,31 are known. Our results indicate a direct correlation between the levels of VEGFA and Id1-Wnt2 pathway. Thus, increased VEGFA (induced by NRG1) was indeed associated with higher Id1/Wnt2 levels in steatotic and non-steatotic livers in CD + LT than in Sham or LT (Fig. 6a). The blockade of NRG1 action (CD + LT+anti-NRG1 group) (which reduced VEGFA levels) was associated with low levels of Id1/Wnt2 (Fig. 6a) when compared with the results observed in the CD + LT group. However, NRG1 inhibition with increased VEGFA (CD + LT+anti-NRG1 + VEGFA) yielded Id1 and Wnt2 similar to CD + LT. In addition to Id1-Wnt2, the PI3K-Akt pathway has also been implicated in VEGFA effects in isolated hepatic cells32. However, this does not occur in our surgical conditions, since changes in VEGFA levels induced by the different interventions (CD + LT, CD+anti+NRG1, CD + LT+anti-NRG1 + VEGFA) were not associated with changes in the protein expression of PI3K/Akt compared to LT or Sham (Fig. 6b). Hence, NRG1 regulated VEGFA, which in turn increased Id1/Wnt2 pathway protection, in steatotic and non-steatotic LT from DCDs.

a Id1 and Wnt2 levels in liver. b PI3K and Akt in liver. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

Role of exogenous NRG1 and its effects on VEGFA in in steatotic and non-steatotic LT from DCDs

Considering protection provided by endogenous NRG1 in liver grafts from DCDs, we evaluated whether administration of exogenous NRG1 could potentiate the benefits induced by the former regarding hepatic damage and inflammation in non-steatotic and steatotic livers. We found that it did not: exogenous NRG1 at 5 mg/kg (CD + LT + NRG1(a)) yielded parameters indicating greater hepatic injury (AST, and vWF levels; Fig. 7a) and inflammation (MDA, and MPO: Fig. 7b) than in CD + LT group. Higher doses confirmed this: double the dose (CD + LT + NRG1(b)) resulted in even more damage and inflammation (Fig. 7a, b).

a AST and vWF levels in plasma. b MDA and MPO levels in liver. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

So, exogenous NRG1 failed to alleviate hepatic damage or inflammation in non-steatotic and steatotic LT from DCDs. The levels of VEGFA after the administration of exogenous NRG1 (CD + LT + NRG1(a) and CD + LT + NRG1(b) groups) increased in comparison to those observed in the CD + LT group (Fig. 8a). However, although the increases in VEGFA induced by the exogenous NRG1, this was associated with a reduction in the levels of both Id1 and Wnt2 (Fig. 8b).

a NRG1 and VEGFA levels in liver. b Id1 and Wnt2 in liver; c Nitrates and nitrites and nitrotyrosine levels in liver. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

To try to explain the harmful effects of the administration of exogenous NRG1, we investigated whether this treatment could be inducing peroxynitrite (ONOO-) formation (known for its potent cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects), generated when NO combines with superoxide33,34,35. This approach was based on: a) studies indicating that NRG1 can affect nitric oxide generation36; and b) reports demonstrating harmful effects of superoxide and peroxynitrites in liver surgery37,38. Importantly, in steatotic and non-steatotic grafts from DCDs, exogenous NRG1 increase NO (measured by nitrates and nitrites) associated with excess nitrotyrosine generation, indicating increased oxidative stress involving ONOO- formation (Fig. 8c). Thus, nitrotyrosine was notably increased in our experimental groups with exogenous NRG1 (CD + LT + NRG1(a) and CD + LT + NRG1(b)), compared to CD + LT group.

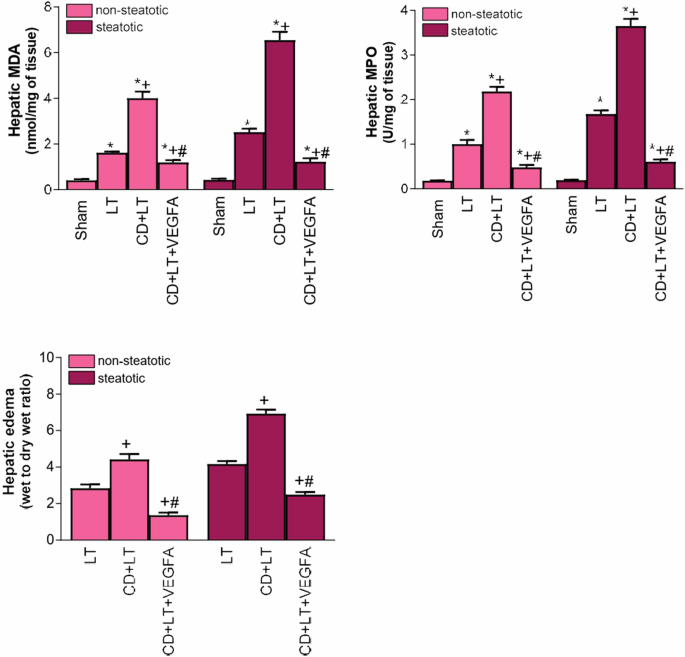

Role of exogenous VEGFA pathway in steatotic and non-steatotic LT from DCDs

As VEGFA is involved in the mechanisms of action of endogenous NRG1, and VEGFA is downstream of NRG1, next we will evaluate whether the administration of exogenous VEGFA is able to potentiate the actions of endogenous VEGFA. Our results indicated that exogenous VEGFA administration (CD + LT + VEGFA group) -which reach to the livers since induced a raise in the VEGFA levels (Fig. 2b)- exerted benefits in steatotic and non-steatotic livers, since reduced hepatic damage (transaminases, damage score, total bilirubin, vWF, HA; Fig. 9) and inflammation (MDA, MPO, and edema; Fig. 10) compared to CD + LT. The extent and the number of necrotic areas were reduced in steatotic and non-steatotic livers in CD + LT + VEGFA compared to CD + LT (Fig. 5). This treatment (CD + LT + VEGFA) (CD + LT + VEGFA), protecting against damage and inflammation, resulted in increased Id1/Wnt2 protein expression compared to CD + LT, LT and Sham, without changes in PI3K/Akt (Fig. 11). Thus, as for endogenous VEGFA (Fig. 6), exogenous VEGFA effects on damage and inflammation might be explained by changes in Id1-Wnt2 signaling pathway protein expression rather than by changes in the PI3k-Akt pathway.

a ALT and AST levels in plasma and damage score in the liver. b total bilirubin levels, vWF, and HA levels in plasma. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

MDA levels in liver tissue as an index of oxidative stress; MPO levels in liver tissue as a parameter of neutrophil accumulation and hepatic edema. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

a Id1 and Wnt2 levels in liver. b PI3K and Akt in liver. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

Effect of endogenosus NRG1 and exogenous VEGFA on pro-and anti-infammatory ILs in steatotic and non-steatotic LT from DCDs

As mentioned above, the levels of NRG1 and VEGFA and those of Id1/Wnt2 (downstream pathway of NRG1-VEGFA) were similar in steatotic and non-steatotic livers of CD + LT. However, differences were observed in the level of liver injury and inflammatory biomarkers in steatotic livers of CD + LT, confirming the lower tolerance of steatotic livers to ischemia-reperfusion. Such results might be explained by a dysregulation between pro- and anti-inflammatory ILs, between both types of liver grafts. Indeed, the induction of CD (CD + LT) resulted in IL-6 and IL-10 (anti-inflammatory ILs) higher in non-steatotic than in steatotic ones, while the levels of IL-1 (pro-inflammatory IL) was higher in the presence of steatosis (Fig. 12). In addition, the effect of NRG1 and VEGFA on both ILs (IL-6 and IL-10) were different depending on the type of the liver (steatotic versus non-steatotic). Indeed, NRG1 inhibition (CD + LT+anti-NRG1) yielded IL-6 and IL-10 in non-steatotic and steatotic livers, respectively lower than in CD + LT, resulting in higher IL-1β in both types of liver grafts. However, the benefits of exogenous VEGFA treatment (CD + LT + VEGFA) on hepatic damage and inflammation resulted in increased IL-6 and IL-10 in non-steatotic and steatotic livers, respectively compared to CD + LT. Under these conditions, IL-1β levels were reduced. The pharmacological modulation of NRG1 or VEGFA (CD + LT+anti-NRG1 and CD + LT + VEGFA) did not induced changes in the levels of IL-10 and IL-6 in non-steatotic and steatotic livers, respectively (Fig. 12).

IL-6, IL-10 and IL-1β in liver. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

Identification of the tissue source of NRG1 and VEGFA in steatotic and non-steatotic LT from DCDs

We next investigated whether liver tissue was responsible for increased NRG1 and VGFA observed in grafts from DCDs at the time of reperfusion. Our results indicated that NRG1 and VEGFA mRNA levels in non-steatotic and steatotic livers from DCDs were similar to Sham or LT (Figs. 13a and 14a). So, we measured NRG1 and VEGFA mRNA and protein levels in adipose tissue from recipients (during reperfusion), based on the adipose tissue–liver axis role in liver diseases39, secretion of mediators derived from adipose tissue to circulation40,41,42,43, and recent indications of the presence and key role of NRG1 in adipose tissue44. NRG1 and VEGFA mRNA and protein levels increased in adipose tissue in CD + LT compared with Sham or LT (Figs. 13a, b, 14a, b). This was associated with increased NRG1 and VEGFA protein levels in circulation and liver tissue in CD + LT compared with LT or Sham (Figs. 13b, 14b).

a mRNA levels of NRG1 in liver and adipose tissue. b Protein levels of NRG1 in adipose tissue, plasma and liver. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

a mRNA levels of VEGFA in liver and adipose tissue. b Protein levels of VEGFA in adipose tissue, plasma and liver. c Protein levels of sFlt1 in plasma. Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean. P < 0.05 versus Sham (asterisk); P < 0.05 versus LT (plus sign); P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

So, we removed peripheral adipose tissue via lipectomy. Now, NRG1 and VEGFA plasma levels in CD + LT + LP were lower than in CD + LT. In line with this, hepatic NRG1 and VEGFA protein levels in CD + LT + LP were lower than in CD + LT, resembling levels in Sham (Figs. 13b and 14b). Thus, adipose tissue provides NRG1 and VEGFA that reach the liver via the circulation.

Next, we investigated whether in adipose tissue, NRG1 was capable of regulating VEGFA in the surgical conditions evaluated in this research. In this sense, when we administered an NRG1 antibody (CD + LT+anti-NRG1 group), NRG1 protein levels in adipose tissue, circulation and liver decreased, compared to CD + LT (Fig. 13b) and VEGFA mRNA decreased in adipose tissue (Fig. 14a). This was associated with reduced VEGFA protein levels in adipose tissue, circulation and liver in CD + LT+anti-NRG1, compared with CD + LT (Fig. 14b). Furthermore, on administering concomitantly NRG1 antibody and exogenous VEGFA (CD + LT+anti-NRG1 + VEGFA group), VEGFA protein levels increased in adipose tissue, and consequently in circulation and liver, approaching those in CD + LT (Fig. 14b). The results show NRG1 increases VEGFA in adipose tissue. So, VEGFA is released into circulation from adipose tissue and consequently taken up hepatically thereby exerting its effects. To confirm this adipose tissue–liver axis role in the NRG1-VEGFA signaling pathway, we administered NRG1 to DCD LT recipients with and without lipectomy. NRG1 supplementation (CD + LT + NRG1(b) group) increased NRG1 in adipose tissue, circulation and liver compared to CD + LT group (Fig. 13b); moreover, VEGFA mRNA and protein levels in adipose tissue, and protein levels in plasma and liver increased (Fig. 14a, b). However, on adipose tissue removal (CD + LT + LP + NRG1(b) group), VEGFA was not generated: reductions in VEGFA protein levels were observed in plasma or liver in CD + LT + LP + NRG1(b) compared to CD + LT (Fig. 14b). Exogenous VEGFA administration (CD + LT + VEGFA group) increased VEGFA protein levels in adipose tissue, plasma and liver compared to CD + LT (Fig. 14b).

sFlt1 can sequester VEGFA from circulation, thereby preventing VEGFA reaching the liver to exert its effects45,46,47, and considering that plasma sFlt1 levels are elevated in different liver diseases48,49, an attempt was made to discern whether, in addition to the key role of adipose tissue on the release of VEGFA into the circulation and the subsequent increase in VEGFA in liver grafts from CD + LT group, such changes in VEGFA levels may be also explained by potential differences in the circulating levels of sFlt1. However, circulating sFlt1 in CD + LT was like Sham or LT (Fig. 14c), indicating a minor role of sFlt1 under our experimental conditions. This was confirmed by administration of an sFlt1 antibody to CD + LT (CD + LT+anti-sFlt1) resulting in VEGFA in steatotic and non steatotic grafts similar to CD + LT. Anti-NRG1 treatment modified plasma VEGFA compared CD + LT, so were measured sFlt1 circulating in CD + LT+anti-NRG1 and CD + LT+anti-NRG1 + VEGFA, resulting in levels like those in CD + LT or Sham (Fig. 14c). We further coadministered VEGFA with an sFlt1 antibody (CD + LT + VEGFA+anti-sFlt1 group) to avoid sFlt1 binding to VEGFA. This yielded VEGFA circulating and hepatic levels similar to CD + LT + VEGFA. Therefore, sFlt1 did not prevent VEGFA reaching the liver to protect against damage and inflammation.

Effect of endogenosus NRG1 and exogenous VEGFA on the survival of recipients with liver grafts from DCDs submitted to prolonged ischemic periods

Survival experiments indicated that recipients of non-steatotic grafts from DCDs submitted to 24 hours of cold ischemia had a survival rate at 14 days after transplantation of 30% (CD + LT(b)). NRG1 Inhibition (CD + LT(b)+anti-NRG1) reduced survival (10%) while VEGFA treatment enhance survival until 70% (CD + LT(b)+VEGFA) (Fig. 15). In recipients of steatotic grafts, lethality was fostered because CD + LT(b) resulted in 10% survival rate. NRG1 Inhibition (CD + LT(b)+anti-NRG1) reduced survival (0%, all animals died) whereas in steatotic DBD LT supplemented with VEGFA (CD + LT(b)+VEGFA) the survival was 60% (Fig. 15). The most of death in recipients with non-steatotic or steatotic grafts of CD + LT(b) and CD + LT(b)+anti-NRG1 occurred at day 1 after transplantation: 7 of 10 rats for non-steatotic CD + LT(b) died, and 9 of 10 rats for steatotic CD + LT(b) died; 9 of 10 rats for non-steatotic CD + LT(b)+anti-NRG1 died, and 10 of 10 rats for steatotic CD + LT(b)+anti-NRG1 died. However, all the deaths in recipients with non-steatotic or steatotic grafts of CD + LT(b)+VEGFA groups occurred at day 2 after transplantation: 3 of 10 rats and 4 of 10 rats died, in non-steatotic CD + LT(b)+VEGFA and steatotic CD + LT(b)+VEGFA, respectively (Fig. 15).

Survival rate at 14 days after transplatation with either steatotic or non-steatotic grafts from DCDs. P < 0.05 versus CD + LT (hash sign).

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate for the first time that endogenous NRG1 is beneficial in non-steatotic and steatotic DCD LT improving liver damage and inflammation and the outcomes with liver grafts submitted to either 4 h of 24 h of cold ischemia. Moreover, CD does not increase hepatic NRG1 prior to LT, but it increased upon reperfusion in DCD graft recipients. We also establish a new endogenous pathway beneficial in DCD LT: NRG1-VEGFA.

In vitro studies suggest PAK1 inhibits cell death15,16; and relationships between PAK1 and NRG1 have been reported in cell lines and BDD LT13,14,18. However, our results indicate that PAK1 plays no role in the benefits of endogenous NRG1 and there is no relationship between NRG1 and PAK1 in DCD LT, thus contradicting the supposed role played by PAK1 and the relationship reported between NRG1 and PAK1.

Similarly, the reported relationship between NRG1 and IGF1 in different cell types and steatotic BDD LT18,23 did not occur in DCD LT. In our hands, IGF1 was not the downstream mediator of the NRG1 pathway in non-steatotic and steatotic LT from DCDs, because the exacerbated damage and inflammation resulting from inhibition of NRG1 was not associated with altered grafts IGF1 levels. These differential effects are no surprising and could be explained by differences in experimental models: a link between NRG1 and PAK1 or IGF1 has been observed in bowel diseases, cancer, isolated cells, and LT from BDDs13,14,18,23 but not in the in vivo surgical DCD LT model used in our current research. Moreover, LT-associated BD and CD involve different complex signaling networks37,50,51,52.

We did find that endogenous NRG1 modulates VEGFA levels in non-steatotic and steatotic LT from DCD. Pharmacologically inhibiting NRG1 decreased VEGFA in both types of grafts, exacerbating injury and inflammation. Therefore, we conclude the NRG1-VEGFA signaling pathway tends to mitigate hepatic damage and inflammation under our surgical conditions, since administering VEGFA (the final effector of this novel pathway) to non-steatotic and steatotic DCD grafts in which NRG1 had been inhibited, prevented the injurious effects of this NRG1 blockade.

Hence, we can report VEGFA as a pivotal mediator of the beneficial effects of endogenous NRG1 in DCD LT, independently of either PAK1 or IGF1.

The downstream mediator of endogenous NRG1-VEGFA pathway in steatotic and non-steatotic LT from DCDs was investigated in the present research. The PI3K/Akt pathway has been implicated with VEGFA in isolated hepatic cells32, but under our conditions, VEGFA effects were unassociated with PI3k/Akt. However, NRG1 induced VEGFA generation, causing up-regulation of Id1/Wnt2 in steatotic and non-steatotic DCD LT, associated with hepatic damage mitigation, and a well-known anti-inflammatory response and protection53,54,55. Reportedly, in hepatectomy with vascular occlusion, VEGFA reduced liver injury and inflammation via different signaling pathways: Wnt2 in non-steatotic livers; PI3K/Akt in steatotic ones22. However, here, in DCD LT, the Id1/Wnt2 pathway was involved in VEGFA protection in both types of graft. Differences between studies subjecting livers to partial hepatectomy with warm I/R and our DCD LT could explain these differences. For instance, in LT from DCD there is no resection and both warm and cold ischemia are present; in addition, reperfusion times when Id1/Wnt2 were assessed, were substantially different in each experimental model. This should be considered since different responses to same therapeutical treatment in livers based on the kind of surgical procedure have been demonstrated previously. This was the case for the effects of angiotensin II in livers submitted either to hepatic resections with I/R or LT38,56. Ofcourse, CD and inherent I/R to LT are two pathological conditions that imply complex mechanistic networks, and when combined, they could result in new molecular signaling pathways that have not been described to date.

After surmising that endogenous hepatic NRG1 protects both types of liver, we evaluated administration of exogenous NRG1. However, this exacerbated hepatic damage or inflammation caused by CD and LT, contrary to results suggesting exogenous NRG1 exerts therapeutic effects in isolated hepatocytes, experimental models of cardiac regeneration or neurodegenerative diseases, and in patients suffering heart failure57,58,59,60. Our results thus indicate that administration of NRG1 is not beneficial in DCD LT, independently of the type of liver (non-steatotic or steatotic). This is consistent with deleterious effects of exogenous NRG1 reported in BDD LT18. Further research is needed to determine if these results extrapolate to clinical DCD LT and then, rule out totally the application of exogenous NRG1.

Differential effects of (endogenous or exogenous) NRG1 have also been reported with other mediators in hepatic I/R and LT61,62. Endogenous and exogenous NRG1 induce changes in VEGFA levels in liver grafts. In our view, the potential benefits of VEGFA induced by exogenous NRG1 might be counteracted by the effects of exogenous NRG1 on the generation of peroxynitrites. NO can act as an antioxidant an antineutrophil, so it has potential to provide protection33,34,35. However, when NO and O2- are at high levels, they combine, generating ONOO- with cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory effects63,64. In our hands, exogenous NRG1 increased NO (measured by nitrates and nitrites) associated with excess nitrotyrosine generation, indicative of increased oxidative stress involving ONOO- formation, which reduces cell antioxidant defenses, interference with signal transduction65 and also promotes inflammation in liver66,67. In addition to the formation of peroxynitrites by exogenous NRG1, dysregulation of cellular Id1-Wnt2 signaling downstream of the NRG1-VEGFA pathway, may also contribute to the observed deleterious effects of exogenous NRG1. Although exogenous NRG1 increased VEGFA, this was associated with reduced Id1/Wnt2 (the downstream signaling pathway of VEGFA): lower than observed in CD + LT, subsequently exacerbating hepatic damage.

It has been described in different pathologies (not related with liver diseases or hepatic I/R) some effects of immune system on NRG1. In this line, in different preclinical models of spinal cord, heart and retinal regeneration in zebrafish, it has been reported that T-reg like cells may have the ability to stimulate different regenerative processes through modulating factors as NRG1 among others68. Another recent study supports the idea that inflammatory myeloid cell-derived IL-1β suppresses the regeneration of intestinal tissue by modifying the secretion of NRG1 by stem-like fibroblasts69. Macrophages, that have also been reported as a cell population with a potential regulatory effect over liver I/R injury70,71 seem to be strongly related with NRG1 since in inflammation-dependent alternative macrophages from inflammatory bowel disease patients seem to express NRG172. In addition, the relation between macrophages and Nrg1 has been described, indicating that M2-like macrophage-mediated regulation of Nrg1/ErbB signaling has a substantial effect on fibrotic tissue formation in a preclinical model of myocardial infarction being critical for apoptosis, senescence and fibrosis development in mice heart73. Therefore, as it has been explained, there are various the immune cells with an important role over I/R liver injury that may affect NRG1 activity so the potential uptake or secretion of NRG1 by the liver as a consequence of immune system different factors should not be completely discarded. Nevertheless, intensive investigations will be required in order to identify an immune-mediated action over NRG1 in the context of liver I/R injury. If this is the case, modulating specific aspects of the innate and acquired immune response might be of interest in terms of potential therapeutic targets.

The current study shows several limitations including more mechanistic approach intra- and extra-hepatically, to elucidate whether there are possible differences based on gender, as well as to evaluate the potential multiple complex interrelations between immune cells and NRG1 in LT from DCD. All this constitutes interesting topics to be addressed in years to come.

Exogenous VEGFA, the final effector of the NRG1-VEGFA pathway, protected steatotic and non-steatotic DCD grafts submitted to either 4 h or 24 h of cold ischemia and potentially can be transferred to clinical settings. Since it is currently impossible to diagnose with precision and accuracy the presence and degrees of steatosis during LT graft procurement74, strategies that benefit steatotic and non-steatotic livers are preferable. So, VEGFA is a serious therapeutic candidate in DCD LT and the NRG1-VEGFA-Id1/Wnt2 pathway offers new mechanistic insight into potential steatotic and non-steatotic graft therapies; the action of endogenous and exogenous VEGFA is related with the Id1/Wnt2 signaling pathway.

Under CD + LT conditions, steatosis had not impact on NRG1-VEGFA but exacerbated damage and inflammation, confirming the lower tolerance of steatotic livers to damaging effects. These results are no surprising since it has been also reported that equal levels of a mediator, for instance when administering NO or cortisol at the same dose, can cause different effects on hepatic injury in steatotic and non-steatotic livers61,75. It is important to bear in mind following evidence. (A) This might be explained by a dysregulation between anti-and pro-inflammatory ILs (IL6/IL10 and IL1, respectively), between both types of liver grafts in CD + LT. Unfortunately, steatotic liver grafts from DCDs exhibit a decreased ability to endogenously generate anti-inflammatory ILs (IL-6 and IL-10) and an increase ability to increase the levels of pro-inflammatory ILs (IL-1β), and consequently high levels of inflammation and damage occur. Additionally, in the setting of LT and CD, the effect of NRG1-VEGFA on both ILs (IL-6 and IL-10) was different depending on the type of the liver: IL-6 for non-steatotic livers and IL-10 for steatotic ones, and this occurred even though both types of livers have similar levels of NRG1 and VEGFA. Both IL-6 and IL-10 have been recognized as playing an important role in providing hepatoprotection against hepatic I/R injury76,77,78,79,80 and both ILs regulate IL-1β (with inflammatory and damaging effects in liver surgical conditions)78,79,80,81,82. (B) it should be considered the huge amount of evidence concerning different signaling pathways underlying injuries of the type I/R in liver that are either steatotic or non-steatotic80,83,84,85,86. In addition, the underlying pathogenic mechanisms sensitivity are probably very different since one involves warm ischemia (here 30 min of cardiac arrest), the other intrinsic functional pathways alteration through fatty infiltration in hepatocytes. Steatotic livers are recognized as pathological87; therefore, it is not surprising that at similar levels of NRG1 and VEGFA in both types the livers, their effects of on hepatic damage may be more pronounced in steatotic liver grafts compared to non-steatotic ones. This is understandable in light of the well-documented variations in molecular mechanisms, as well as morphological and functional differences, between steatotic and non-steatotic livers during I/R injury, which is inherent to LT88,89. (C) Levels of NRG1 and VEGFA in liver do not determine the extent of liver damage or the susceptibility of steatotic livers from DCD undergoing LT. The role of a mediator in liver injury is evidenced by pharmacologically altering its activity and noticing changes in liver damage parameters, as we have observed in the current study with NRG1 cand VEGFA, and also validated with numerous previous studies56,61,80,90,91,92. Importantly, in steatotic grafts, administering for instance VEGFA led to greater mitigation in some parameters of liver damage and inflammation compared to non-steatotic livers.

BD increases hepatic NRG1 before and during LT; hepatic cold ischemia also increases NRG1 in experimental BDD LT18. However, in our DCD LT study, both non-steatotic and steatotic NRG1 levels were similar in Sham, Prior to LT and Prior to CD + LT. So, CD does not increase hepatic NRG1 before graft implantation, but NRG1 was increased in recipients. This might be expected as BD and CD are extremely different, involving molecular signaling through different networks of mediators37,50,51,52, suggesting NRG1 was generated at different LT times, depending on BD or CD.

NRG1 and VEGFA could not be explained by an increase in the synthesis of NRG1 and VEGFA in liver. Next, based on the involvement of adipose tissue in liver diseases39, and reports of NRG1 in adipose tissue44, we investigated if adipose tissue is associated with increased NRG1 and VEGFA in DCD grafts at reperfusion. We found NRG1 and VEGFA levels were higher in adipose tissue, circulation and liver tissue of recipients of CD + LT than in basal groups without CD (LT and Sham). Withdrawing peripheral adipose tissue, such increases were no longer observed. Taken together, our results demonstrate for the first time, that the increases in NRG1 and VEGFA observed in steatotic and non-steatotic DCD grafts during reperfusion in the recipient are derived from adipose tissue, which secrets NRG1 and VEGFA to circulation where they are taken up by the liver, thus mitigating the harmful effects of CD (Fig. 16). Moreover, regulation of VEGFA by NRG1 occurs in adipose tissue, since when NRG1 action was blocked (CD + LT+anti-NRG1), VEGFA was reduced in adipose tissue, circulation and liver: NRG1 could not trigger adipose tissue to send VEGFA into circulation, resulting in aggravated damage and inflammation. The combination of pharmacological blockade of NRG1 and exogenous VEGFA supplementation in DCD LT (CD + LT+anti-NRG1 + VEGFA), restored VEGFA in adipose tissue, circulation and liver of the recipient, abolishing detrimental effects from inhibition of NRG1. Lipectomy and supplementation of exogenous NRG1 (CD + LT + LP + NRG1(b)) proved the key participation of adipose tissue in the NRG1-VEGFA pathway in DCD LT: with adipose tissue, exogenous NRG1 (CD + LT + NRG1(b)) augmented VEGFA in adipose tissue, plasma and liver at reperfusion time of recipients of transplanted grafts from DCD. In contrast, when peripheral adipose tissue was absent and NRG1 was also administered (CD + LT + LP + NRG1(b) group), despite the presence of exogenous NRG1 in plasma and liver in recipients of transplanted grafts from DCD, VEGFA was not induced and then, did not increase neither in plasma nor liver of recipients.

In CD + LT, NRG1 increases VEGFA in adipose tissue from recipients during reperfusion. Then adipose tissue secretes VEGFA to circulation and it is up taken by the liver to mitigate the damaging effects induced by CD. Indeed, in CD + LT + LP, such increases in NRG1 and VEGFA were no longer observed. Under NRG1 inhibition (CD + LT+anti-NRG1), VEGFA levels were reduced in adipose tissue, circulation and liver, because there is no NRG1 available to generate VEGFA in adipose tissue to be delivered into circulation and liver to lessen injury. Such reduction in VEGFA in adipose tissue, circulation and liver were not observed when administrated concomitantly NRG1 antibody and exogenous VEGFA (CD + LT+anti-NRG1 + VEGFA). NRG1 administration (CD + LT + NRG1(b)) increased NRG1 in adipose tissue, circulation and liver. Under such conditions, the levels of VEGFA were increased in adipose tissue and consequently in circulation and liver. However, lower Id1/Wnt2, (pathway downstream VEGFA) and increased peroxynitrite production and exacerbated damage and inflammation were observed. Lipectomy combined with NRG1 in recipient (CD + LT + LP + NRG1(b) group) led to higher NRG1, but reduced VEGFA in either plasma or liver of CD + LT + LP + NRG1(b) than in CD + LT group. Thus, in absence of adipose tissue, NRG1 was not able to increase VEGFA in either circulation or hepatic tissue. Furthermore, VEGFA administration (CD + LT + VEGFA) increased VEGFA levels in adipose tissue, circulation and liver thus alleviating hepatic damage and inflammation.

We next evaluated whether the levels of circulating sFlt1 in DCD LT sequestrate exogenous VEGFA, reduce circulating VEGFA bioavailability, and consequently restrict its uptake by the liver and protection. In warm ischemia under vascular occlusion, circulating sFlt1 may determine VEGFA availability and its effects on target organs22, in line with increases in circulating sFlt1 in liver cirrhosis and chronic kidney disease48,49,93. However, circulating levels of sFlt1 in CD + LT and groups where NRG1 was pharmacologically modulated were unchanged compared with Sham; inhibition of sFlt1 action in CD + LT to avoid sFlt1 binding to VEGFA (alone or combined with exogenous VEGFA) resulted in hepatic VEGFA levels similar to those observed when VEGFA was administered alone. So, in our conditions, circulating sFlt1 did not sequestrate exogenous VEGFA. The minor role of sFlt1 contrasts with previous reports48,49,93 indicating that the role of sFlt1 is specific depending on the different liver diseases and surgical condition (warm ischemia associated with hepatic resections)22 versus LT from DCD as in our study.

Chronic donor shortages mean DCD LT is increasing. However, post-graft survival rates are lower and primary nonfunction more common with such organs. Warm ischemia prior to cold ischemia, and hepatic steatosis both contribute to these undesirable complications52,94,95. The adipose tissue–liver axis plays a crucial role in the NRG1-VEGFA signaling pathway in steatotic and non-steatotic DCD LT in recipients but not donors. When CD is induced in non-steatotic and steatotic donors, at reperfusion, adipose tissue from recipients generates NRG1, inducing VEGFA production, which is secreted into circulation and taken up hepatically, mitigating harmful CD effects. NRG1-VEGFA promoted the expression of Id1/Wnt2 in liver from recipients (Fig. 16), clearly associated with diminished hepatic damage and inflammation. So, in the pathology of DCD LT with non-steatotic and steatotic grafts, endogenous NRG1 exerts its beneficial effects via the VEGFA-Id1/Wnt2 signaling pathway. Our results also modify the dogma that exogenous NRG1 administration is always beneficial since under the conditions evaluated here, exogenous NRG1 is not appropriate in non-steatotic or steatotic DCD LT. Both types of DCD liver grafts benefit from exogenous VEGFA administration in the recipient; this pharmacological approach could increase organ donor pools. As VEGFA supplementation is equally effective with or without steatosis, clinicians did not have to worry about the presence or degree of fatty infiltration in liver grafts. These findings show that VEGFA administration could be an effective strategy in real clinical situations of DCD LT. Obviously, intensive research is necessary to determine whether these experimental results extrapolate to clinical practice in DCD LT.

Responses