The role of rivers in the origin and future of Amazonian biodiversity

Introduction

The Amazon biome contains more species than any other region on Earth1. Although often referred to as a forest, Amazonia is a complex mosaic of intertwined environments thriving in a monsoonal climate2,3. The history and current distribution of the Amazonian biota are intrinsically linked to the development and seasonal dynamics of the world’s largest fluvial system, which extends from highlands in the Andes and on the Guiana and Brazilian plateaus to the equatorial Atlantic Ocean4. This drainage network determines which areas are flooded during the austral summer when the South American monsoon is active3 and distributes nutrients and sediments across the lowlands5 and to the ocean. Sediments deposited by Amazonian rivers build floodplains, which are later converted into sedimentary non-flooded uplands by fluvial incision6,7. Consequently, rivers control the spatial distribution of the different Amazonian environments, and how they change through time spans ranging from thousands to millions of years.

Geological and climatic processes throughout the Neogene period (23.03–2.58 million years ago (Ma)) and the Pleistocene period (2.58–0.011 Ma) established the transcontinental river and drainage system observed today8,9, characterized by upland and seasonally flooded environments in lowland Amazonia6,10,11. During the Holocene epoch (0.011 Ma to the present), humans established populations within Amazonia, driving large-scale ecological shifts12. Following European invasion, intensive exploitation of natural resources involving infrastructure development and land-use change caused rapid changes to the Amazonian fluvial system13.

The rivers of Amazonia and their floodplains provide and regulate connectivity for species adapted to aquatic and seasonally flooded habitats14. However, these rivers and floodplains are barriers to dispersal for species that inhabit the upland non-seasonally flooded terra firme environments15. Thus, historical changes in drainage configuration have affected the diversification of ecologically distinct taxa in unique ways16, contributing to the complex patterns of diversity and distributions seen today17. Our understanding of the relationship between Amazonia’s rivers and biodiversity remains incomplete. However, this complex system is under threat from anthropogenic factors driving rapid change13, including damming of rivers18, riverbed and floodplain mining, and forest degradation, habitat loss and fragmentation in interfluvial and catchment areas19,20. The effects of these changes are enhanced by extreme climatic events fuelled by global warming20.

Amazonia’s rivers and seasonal flooding also sustain ecological interactions that maintain its biodiversity and are essential to Indigenous peoples and local communities21,22. The disruption of these interactions could trigger cascading effects, accelerating the degradation of the Amazonian biome and jeopardizing food security and the ways of life of Indigenous peoples and local communities. An integrative multidisciplinary and multicultural approach is essential to advance the debate about Amazonia’s history, current threats and possible futures.

In this Review, we explore the patterns and processes of diversification in Amazonia driven by the interactions of biodiversity with fluvial environments and mediated by ecological traits. Throughout, we focus on the biota associated with terrestrial and seasonally flooded environments, because the processes driving distribution and diversification of freshwater aquatic organisms are vastly distinct. We first describe the spatial and temporal variation of Amazonia’s drainage system, before exploring the various theories regarding the origin of the region’s rich biodiversity. We then discuss the biotic diversification associated with specific riverine subbasins, and the variety and distribution of threats to the Amazonian river network. Finally, we propose a hypothesis-testing framework for the future study of Amazonia, based on the heterogeneity of the distinct regions and rivers, that integrates knowledge from different scientific fields and cultural backgrounds.

Rivers structure Amazonian biogeography

In 1852, Alfred R. Wallace noted that distinct species of primates occurred on the opposite margins of large Amazonian rivers23,24. Following those observations, scholars have debated whether rivers are important in the regionalization of Amazonian biodiversity. These debates are often focused on groups for which more taxonomic, diversity and distribution data are available, such as birds and primates. For these groups, most taxa are not widely distributed across Amazonia and their distributions are delimited within common areas called areas of endemism25.

Recognized areas of endemism for birds26,27, primates28,29,30,31 and butterflies32 mostly correspond to Amazonian interfluves, with the large Amazonian rivers as their limits (Fig. 1). This pattern has also been observed for lizards33,34, frogs35,36 and vascular plants37,38. Distribution data for 620,000 Amazonian bird specimens from more than 10,000 localities has identified ten zoogeographical regions largely congruent with previously described interfluvial areas of endemism39 (Fig. 1c). Only approximately 23% of Amazonian bird taxa and 10% of Amazonian primate species occur in three or more of these zoogeographic regions, corroborating early observations that most Amazonian taxa are not widespread in the vast Amazonian region (see refs. 39,40,41 and The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species).

a,b, Variations in community compositions in Amazonia for species of terrestrial vertebrates (a), and subspecies of birds (b), with colours indicating differences in community species/subspecies composition. c, Areas of endemism based on the congruence of species distributions within Amazonia. Areas have been delimited with different methods throughout the literature. The interfluvial areas presented in c are based on analyses of bird species endemism. d, The difference between the number of recognized species (lighter shading) and total taxonomic units (species combined with subspecies, darker shading) for Amazonian birds, demonstrating the potential to underestimate total diversity when only species-level taxa are considered. In all maps, north is at the top. Amazonian areas of endemism have distinct community compositions with high taxonomic disparity. The data in panel a are from the IUCN Red List and the BirdLife International State of the World’s Birds: 2023 Annual Update, data in panel b are from ref. 39, panel d adapted with permission from ref. 39, Wiley. Multidimensional scaling analyses in panels a–c follow ref. 39.

For other taxonomic groups, such as bats42, termites43 and ferns44, the effect of rivers in shaping distribution patterns and community composition is not evident. Other factors including geographic distance, terrain elevation, environmental heterogeneity and climate are cited as strong drivers of current distributions45. In some groups, this pattern could be due to variations in dispersal capacity (bats) or dispersal mode (ferns). However, incomplete taxonomic knowledge can also affect the ability to detect refined patterns of distribution (Box 1).

Contributing to this complexity, the rivers of Amazonia are highly heterogeneous in terms of their aquatic, seasonally flooded and upland bounding environments, development history, and potential effectiveness as barriers to upland biotic dispersion through time. Thus, although the biogeographic literature on Amazonian riverine barriers tends to treat all rivers as analogues46, this approach should be refined according to the different abiotic characteristics and historical development of specific rivers.

The spatial congruence between current species distributions and river channels suggests that biotic diversification and drainage development might be linked through Amazonian history. However, this hypothesis needs more mechanistic testing, including reconstruction of evolutionary trajectories, understanding of the relationships of organisms with the environments they occupy, and reconstruction of the spatiotemporal development of the riverine landscape.

Amazonian rivers through time

At present, large rivers are important determinants of the spatial distribution of Amazonian biota and ecosystems. However, Amazonian rivers themselves are constantly evolving and have been through many local to regional shifts over time spans of thousands to millions of years, with drivers ranging from tectonic processes47 to climate changes6,48. In this section, we discuss the shifts in the Amazonian drainage system through time and their effects on regional heterogeneity.

Amazonian drainage evolution

During the Cretaceous period (145–66 Ma) and possibly during the Palaeogene period (66–23.03 Ma)9, the region that now corresponds to Amazonia was comprised of local sandy river systems that flowed into extensional tectonic basins aligned in an east–west direction49. Subsidence mechanisms and the resulting deposition of sediments, which are more easily erodible than the Precambrian shield rocks even when lithified, led to a long-lasting east–west depression between the Brazilian and Guiana shields50 (Fig. 2). This depression controlled the orientation and position of the modern Amazon River basin, as well as the spatial distribution of rivers with wider floodplains over soft sedimentary terrains or rivers with bedrock rapids in shield terrains.

Colours indicate ages for the surface geological units in the region. Dark lines mark the current locations of main river channels. Amazonian rivers flow over distinct geological terrains, influencing how they change through time. The area northward of the Solimões–Amazonas River corresponds to Precambrian (Proterozoic) rocks of the Guiana Shield. Conversely, rocks of the Brazilian Shield correspond to Proterozoic units southward of the Solimões–Amazonas River. Areas drained by western alluvial rivers are represented by Neogene and Quaternary units. Valleys incised into Cretaceous and Palaeogene units outcropping along the Solimões–Amazonas River eastward of the Negro and Madeira Rivers give origin to ria lakes in the Negro, Trombetas, Tapajós and Xingu rivers. Data for the map are adapted with permission from ref. 171, Servicio Geologico Colombiano (SGC).

The effects of tectonic forcings on the Amazon River basin have been modelled both numerically47 and conceptually51. Tectonic events modelled in this way include the origin of the Amazon headwaters during the initial uplift of the Andes in the Cretaceous and uplift acceleration in the Miocene (23.03–5.33 Ma)52,53 and the establishment of a transcontinental river system reaching the Atlantic Ocean. Tectonic events during the Miocene epoch led to the development of a large-scale depression, the Pebas System, in western Amazonia51, likely to be related to the flexural loading of the Andes and the effects of plate subduction in the mantle beneath the northern part of the South American Plate54. Sedimentary records of the Pebas System found in the Pebas and Solimões formations contain a Late Miocene fossil record of land and aquatic vertebrates, as well as freshwater invertebrates and possible marine invertebrates in specific stratigraphic levels55,56,57. Hence, the Pebas System records that western Amazonia hosted a Miocene wetland and/or shallow-water environment, eventually connected with the Caribbean Sea57, before establishment of the eastward-flowing fluvial system connecting the northern Andes with the Atlantic Ocean.

The gradual infilling of the sub-Andean Pebas System with Andean-derived sediments is the most plausible explanation for the connection between the western drainage system and the eastern Atlantic river basin47,58, giving rise to the current transcontinental configuration of the Amazon River basin. Alternatively, the first transcontinental drainage connecting the Andes and the Atlantic Ocean might have occurred via the Madeira River, including the sedimentary filling of the Madre de Dios basin in Bolívia59. Dynamic topography driven by mantle convection is another potential mechanism leading to continental-scale drainage reorganization. In this scenario, the onset of the Pebas System would have resulted from long-term subsidence (101 metres per million years) and the end of the system would have resulted from a subsequent uplift provoked by subducted flat slabs migrating eastward, forming an eastward-sloped lowland drained by rivers connecting the Andes and the equatorial Atlantic54. The first transcontinental drainage path and timing are still uncertain, but provenance in marine sediment cores near the mouth of the modern Amazon River indicate an age of at least 9 Ma for the onset of the connection60.

The establishment of a transcontinental drainage system and the associated transformation from a major wetland environment in western and central Amazonia into lowlands dominated by rivers and floodplains are key elements in the history of Amazonian palaeogeography51,61. Nevertheless, changes in the configuration of the drainage systems and the resulting landscape transformations continued to influence species distributions throughout the Pliocene (5.33–2.58 Ma) and Pleistocene epochs6,11,15,62.

Changing configuration of the drainage system

Changes in the configuration of the Amazon drainage system include channel-reach repositioning in two different contexts: channel avulsion during base-level rise, and channel capture, which is more frequent during base-level fall.

Channel avulsion occurs when a fluvial system disperses and deposits sediments across a wide and unconfined basin, distributing water and sediments in large fan-shaped structures called megafans63. In these systems, sediments tend to accumulate at channel margins (aggradation), leading to the formation of alluvial ridges that are higher than the adjacent floodplains. This accumulation eventually results in bank rupture and diversion of channel waters into low-lying areas. Wide areas of Pleistocene terrace surfaces in western and central Amazonia display scroll bar structures64 indicative of palaeochannels now at a higher base level and thus disconnected from active channels6. The process of channel avulsion has a decadal to centennial recurrence time and is mostly restricted to floodplains, although their effect on upland areas needs further investigation. Accordingly, avulsions probably have few implications for the barrier effect of rivers for upland terra firme species65 but can cause dynamic changes in connectivity and population sizes for floodplain-associated populations11.

By contrast, river-capture events are caused by advancing incision pulses resulting from base-level fall66. River capture occurs when the headwaters of a small river retreat and reach the valley of a large river and the large river starts flowing into the small river valley. As the capture process depends on headwater erosion, it is more frequent in areas where rivers flow over unconsolidated soft sedimentary successions, such as in western and central lowland Amazonia64. River capture of the main reaches in large shield rivers (rivers flowing over Precambrian shields formed by igneous and metamorphic rocks) is possible, but is less frequent and slower, owing to the lower erodibility of the shield bedrocks. This is evident in the ongoing river capture of the Casiquiare River, in which the Negro River is capturing the upper Orinoco River67.

Amazonian rivers flow over heterogeneous terrains formed by diverse rock types and hosting structures, such as fractures and boundaries between geological units, that influence knickpoint location and river courses. For example, boundaries between rocks of contrasting erodibility can determine channel direction and be focal points for drainage capture and rearrangement68. Thus, the geological heterogeneity of the substrate of Amazonian watersheds can act as an autogenic control for drainage shifts, decoupled from contemporary climate or tectonics. Substrate heterogeneity in areas under uplift is inherited from the overlap of past geological events but can influence the modern riverine landscape. Progressive knickpoint propagation can eventually lead to the capture of large rivers, emerging as an alternative explanation for grand regional shifts in the Amazonian fluvial landscape69.

Besides autogenic controls, channel avulsion and river capture are also influenced by climatically driven variations in water and sediment discharge related to precipitation changes driven by insolation cycles, such as precession cycles that have a periodicity of around 23,000 years70. Channel avulsion and river capture might also be driven by variations in base water level induced by sea-level changes, which occur following glacial–interglacial cycles and have a periodicity of approximately 100,000 years. Sea-level changes lead to delayed effects on large fluvial systems. Sea-level fall causes the lowering of the river base level, triggering riverbed erosion beginning close to the coast. The resulting increased slopes in the river profile drive the upstream propagation of the incision pulse over thousands of years. Increased river discharges also cause rivers to incise into their valleys. Both mechanisms potentially reduce floodplain area, because channel incision lowers the maximum vertical reach of floodwaters71. The consequences of such a process include the rapid transformation of large areas of floodplains into uplands that are not flooded6,11. Conversely, base-level rise associated with sea-level rise and/or reduction of river discharges results in net sediment deposition in river systems. These aggradational scenarios favour the expansion of floodplain environments, enabling the gradual lateral migration of river channels onto their respective valleys and channel avulsion in unconfined lowland areas. Sedimentary successions from the extensive Pleistocene terrace systems in western and central Amazonia record fluvial deposition in unconfined environments at different base levels during the Late Pleistocene. The last phase of floodplain expansion occurred after the Last Glacial Maximum (approximately 21,000 years ago) when a rising sea level and precessional strengthening of the South American monsoon favoured base-level rise and sediment accumulation in river valleys11. Tracking incision and aggradation phases in periods before the Late Pleistocene (older than 129,000 years) is still difficult owing to the lack of age constraint for the development of fluvial terraces in higher-elevation Amazonian interfluves.

Regional heterogeneity within Amazonia

The western and eastern Amazonian fluvial systems evolved in contrasting ways. The western depression is characterized as a large area of low-lying terrains formed by the infilling of the Pebas System during the Neogene period (23.03–2.58 Ma) (Fig. 2). During the Late Pleistocene, this area was occupied by highly dynamic megafan systems that reacted to changes in base level caused by variations in discharge and sea level. These changes led to distinct environmental shifts between flooded and unflooded areas and local episodes of river-channel capture, affecting the middle and lower courses of the Negro, Japurá, Solimões, Juruá, Purus and Madeira river basins. The eastern portion of the Amazon basin has been characterized by large rivers with narrow floodplains, such as the Tapajós and Xingu, flowing into stable valleys for longer periods of time, with limited evidence of river-capture events, and environmental responses to base-level change being limited to the valley areas. However, the watersheds of these eastern Amazonian rivers have headwaters in the Cerrado Brazilian savannah, which has a hydroclimate susceptible to frequent severe droughts72,73 owing to connections with the northeastern and southern Brazil climates74. As such, drought events can frequently reduce floodplain extension and connectivity. Thus, the western and eastern Amazonian rivers have demonstrably varied historical development and differing susceptibility to changes in their floodplains and pathways.

Coupling drainage and biodiversity evolution

The geological and climatic history of Amazonia has greatly constrained the environmental and ecological variation of the region (Fig. 3). Over time, emerging methods and advancing taxonomic knowledge have enabled quantification of this influence on the evolution of the extremely diverse Amazonian biota.

a–i, Habitats in terra firme environments vary across Amazonia (main panel). Colours correspond to habitat types across the region, based on a combination of soil and vegetation data. The georeferenced field photographs depict representative habitat types: a, open savannah habitat dominated by grasslands; b, terra firme understory crossed by a small creek; c, open canopy white sand environment (WSE)172 with dispersed bushes and small trees; d, understory of WSE forest; e, understory of terra firme forest; f, area dominated by Chusquea bamboo (credit: Tomaz N. Melo); g, understory with prevalence of Lepidocaryum tenue; h, open canopy WSE; i, understory of drier upland forest in eastern Amazonia. Map colour channels are based on principal component analysis of soil organic matter concentration determined by soil pH at 15 cm of depth, using bands 1, 2, 6 and 7 from Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Aqua and Terra sensors. The red, green and blue colours correspond to principal components 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Soil data are from ref. 173 and MODIS data are from ref. 174. Even within upland terra firme forest there is marked heterogeneity between distinct regions of Amazonia.

Diversification hypotheses

The discussion about the origin of high Amazonian species diversity has long been framed by competing diversification hypotheses75. The refugia hypothesis76 proposed tropical climate variations induced by Pleistocene glaciations as the main driver of changes in habitat distribution, leading to ecological barrier formation and speciation of forest taxa. However, the observation that rivers constrain biotic dispersal and shape taxa distributions has supported an alternative explanation for diversification: the riverine barrier hypothesis15,77. The perception that Amazonian rivers experienced major changes during the Miocene51 and that glaciation-induced changes in vegetation cover occurred during the Pleistocene led to a simplistic hypothesis-testing framework in which Pleistocene diversification was assumed to be related to refugia whereas older diversification was assumed to be related to drainage development16,78. However, as discussed previously, both the drainage system and the climate were dynamic and coinfluential15 during the Pleistocene. The interplay between climate change and riverine barriers is considered in the proposal of the river-refuge hypothesis28,79. This hypothesis posits that the combination of riverine barrier effects (which are weaker at river headwaters) and climate variation (which causes the retraction of rainforest toward the centre of the biome and away from headwaters) can contribute to the effective isolation of populations. Genomic analysis of populations close to the headwaters of the Teles Pires river suggested that hybridization does occur, but is spatially restricted, indicating that speciation might occur with some parapatric contact, or that the headwater regions might support sink populations that fail to homogenize sister populations even with inward gene flow80.

The long discussion about the role of riverine barriers or refugia in the origin of Amazonian species exemplifies how current patterns of diversity and distributions are often used to discuss diversification hypotheses45; however, the current distributions of species are not sufficient evidence for testing hypotheses about historical processes of diversification15,16,81. Testing historical hypotheses requires data obtained from the reconstruction of phylogenetic and population histories15.

Molecular tests of historical hypotheses

Mechanistically, disruptions to dispersal, and consequently reduced population connectivity, are fundamental to diversification because isolated populations accumulate genetic differences, eventually leading to speciation2. Tests for linkages between diversification and the development of drainage systems rely primarily upon molecular data from which the geography and timing of genetic differentiation can be estimated, although this estimation is not without challenges (Box 1). The application of a molecular clock can estimate divergence times using the degree of genetic differences separating taxa. Comparison of divergence times to the geological history of the Amazonian fluvial system has in turn been used to support interpretations about the drivers of diversification of Amazonian biota2,16,51.

Tests based on the timing of divergence can be applied to any organism for which sequence data are available. However, several assumptions must be made to assign the driver of diversification to the river barrier itself when using such an approach. Most biogeographic studies interpreting the geological history of the Amazonian fluvial system assume that the river channels behave as continuous barriers throughout time, and that shifts in their positions are episodic82. Under this assumption, most of the landscape, dominated by upland terra firme forest, has been relatively stable in the long term, and any major changes were related to the presence or absence of specific riverine barriers that split populations causing diversification. However, as discussed previously, the riverine landscape has been highly dynamic even as recently as the Late Pleistocene6,11,58, with local rearrangements in river-channel connections and positions83 and regional variation in the extent of seasonally flooded and unflooded terrains supporting distinct kinds of habitat6. Therefore, the presence or absence of a river channel across a specific area in the present day does not necessarily capture the complex scenarios that characterize regional histories, which potentially complicates tests based on species distributions and divergence times. Likewise, seeking general conclusions about the role of riverine barriers by treating the different Amazonian rivers in the same way overlooks the important historical and physical characteristics of individual rivers. These singular characteristics of distinct rivers might result in varying levels of coincidence between current river channels and species diversity patterns, divergence times or degree of genetic isolation.

Trait-based predictions

Species-specific functional traits can complicate the interpretation of the roles of riverine barriers in diversification. To test the generality of a hypothesis of diversification history, studies often rely on evaluations of the congruence of divergence histories across multiple taxa84. However, interpretating these evaluations must be done cautiously because of strong assumptions and potential biases in such tests. Given limited information about species distributions and taxonomy (Box 1), there is the risk that estimated divergence times for non-sister taxa or clades might be included and misidentified as sister taxa, inflating the variance in divergence times. Because the lack of congruence of divergence histories implies that there has been gene flow across the river in some taxon pairs, the river barrier hypothesis could be rejected when the lack of congruence might reflect a compromized study design. Even if sister taxa have been accurately identified, reliance on congruence criteria makes assumptions about the nature of riverine barriers. Specifically, it ignores the effects of taxon-specific traits, such as habitat affinities that modulate both the strength of barriers and the connectivity among populations through time85,86,87.

Under the assumptions discussed above, the rejection of global concordance for all clades within a studied region independent of their traits and habitat affinities leads to poor predictive power. It is better to rely on refined hypotheses in which predicted concordance reflects shared species functional traits, which provide more insightful tests88. For example, different species have evolved specific adaptations to the different Amazonian environments (Box 2) and therefore use habitats differently; for biota associated with non-flooded terra firme habitats, large rivers can be barriers, whereas they can be dispersal corridors for biota associated with seasonally flooded igapó and várzea habitats89. Testing for concordance in genetic divergence across taxa with shared functional traits provides a more meaningful test for the shared effects of riverine barriers than those that assume global concordance. Even closely related taxa associated with the same kind of habitat can differ in their dispersal capabilities and perceive barriers differently, as has been shown for understory and canopy birds90,91. As such, there is no reason to expect concordant distribution patterns and common diversification processes for different groups of taxa solely on the basis of co-occurrence within Amazonia.

Modelling biodiversity patterns

Spatially explicit mechanistic models can simulate geographical patterns of biodiversity. Models that include both ecological and evolutionary processes92,93 have been applied at continental scales and could offer an alternative route to reconstructing diversification history and investigating the roles of landscape change. These models can accommodate spatiotemporally dynamic landscapes and integrate multiple macroecological and macroevolutionary processes that shape biodiversity, including adaptation, range shifts and fragmentations, speciation, interspecific competition and extinction. The simulated biodiversity output of these models, including species richness maps, phylogenetic metrics, species ranges and ecological traits92,93, can then be compared with maps and metrics derived from empirical data for the focal taxa. A resemblance between the simulated outputs and empirical data can confirm the role of potential processes as drivers of diversification. Although mechanistic models can offer insights into the processes that shape biodiversity, using them can be challenging. The estimation, optimization and interpretation of model parameters, as well as the measurement of the goodness of fit between observed data and model predictions, are not straightforward procedures and require the application of additional techniques such as pattern-oriented modelling94,95.

In general, to reconstruct the relationships between the evolution of the biota and the changing characteristics of the landscapes through time we need to make use of both genomic and geological data, mediated by ecological information (essential to guide any interpretations). This crucially multidisciplinary approach is the core of biogeographic and geogenomic investigations and is particularly challenging for megadiverse biotas in highly heterogeneous landscapes, such as Amazonia.

Rivers and biotic diversification

Considering the heterogeneity of Amazonian environments and fluvial system (Figs. 2 and 3), relationships between drainage development and biotic diversification are best presented regionally. Below, we consider both the specific geological context of watersheds and the ecological affinities of taxa to review existing evidence on biotic diversification associated with the main Amazonian rivers.

Amazon River

In the lowlands, the mainstem of the Amazon River, including the Solimões River (the Amazonas River west of the Negro River mouth, in Brazil), drains heterogeneous terrains of varied erodibility and elevation (Fig. 2), which determines channel and floodplain width and stability through time. In the western lowlands, it flows over the Neogene and Quaternary soft sedimentary deposits of the Solimões sedimentary basin and in the east it cuts across the Palaeozoic–Mesozoic rocks of the uplifted Amazonas sedimentary basin (Fig. 2). The upper and lower portions of the Amazonas–Solimões River have distinct histories and were independent before their connection in the same transcontinental eastward-flowing watershed. This connection initiated a regional and long-lasting shift in the landscape, with consequences for both non-flooded and seasonally flooded habitats and their associated biota. Watershed expansion following the connection of the rivers led to a mainstem channel with increased water discharge and floodplains, both enhancing the barrier effect for upland forest species and establishing a wide and continuous corridor across the entire equatorial lowlands for species adapted to seasonally flooded habitats. Although there is geological evidence that Andean-sourced sediments reached the Atlantic Ocean, travelling across eastern Amazonia during the Late Miocene96, the estimated time for the fluvial connection between Andes and the equatorial Atlantic is still debated, encompassing the Miocene51,60,69,96, Pliocene8,59,97 or Pleistocene epochs98,99. This variance in estimation indicates that the chronology of biotic diversification could contribute to understanding this history100.

The Amazon River is an important biogeographic barrier both for community composition101 and for delimiting lineage distributions62,81. However, the ages of diversification events associated with this riverine barrier vary depending on their location along the Solimões–Amazonas River, both for populations adapted to seasonally flooded várzea and for those adapted to upland terra firme environments. Diversification events related to the Amazon River are often the oldest ones in the phylogenetic history of Amazonian clades81, which could be explained by the long-lasting persistence of large floodplains along this river with its extended west–east and south–north watershed, reducing the sensitivity of this river to geographical climate variability. On average, diversification events associated with the Solimões River (the upper portion of the Amazon River) are more recent than those associated with the lower portion of the Amazon River (Fig. 4). The ages of diversification events vary among clades even when comparing taxa associated with the upland terra firme forest, although most events are more recent than the Miocene, which is among the proposed ages for the establishment of the transcontinental Amazon River.

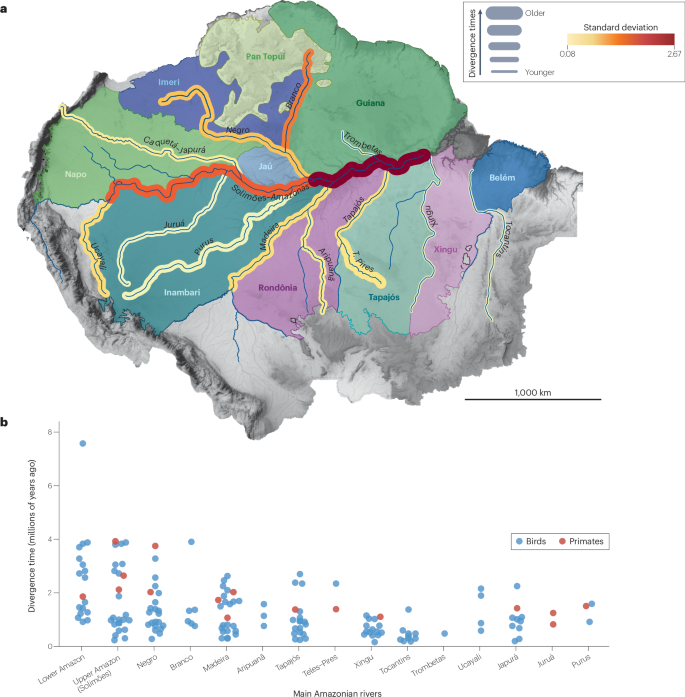

a, Amazonian areas of endemism and riverine barriers. The riverine barrier width corresponds to the average time divergence of sister clades separated by that barrier. Riverine barrier colour indicates the standard deviation of all the clade splits associated with that river. b, Divergence time for splits between sister clades of birds (blue) and primates (red) across the main Amazonian rivers, based on molecular phylogenetic dating. Data for panel b located in Supplementary Data 1. There is substantial variation in diversification dates related to each riverine barrier, but older splits are mostly associated with the Amazonas, Solimões and Negro rivers, and the most recent splits are mostly associated with Brazilian Shield rivers such as the Tapajós and Xingu.

For birds and primates from upland terra firme forests, most diversification events across the Amazon River date to the past 4 Ma (Fig. 4). For amphibians, small distribution ranges and many as-yet-undescribed species102,103 (Box 1) preclude a finer association of diversification events with specific barriers, although there is evidence of distinct histories in eastern and western Amazonia, with Miocene-to-Pleistocene diversification in western Amazonia36,104,105 and older diversification events associated with the lower Amazon River in eastern Amazonia106. For birds that occur along the Amazon River floodplains, a common genetic discontinuity is found between the mouths of the Negro and Madeira rivers, further characterizing the distinct histories associated with the upper (Solimões) and lower Amazon River14. Reconstruction of historical sedimentation dynamics along the Amazon River floodplains indicate Pleistocene cycles of expansion and retraction related to precipitation and base-level variation6,7, which drive the genomic organization86 and demographic history of floodplain bird populations, in a clear link between riverine dynamics and biotic diversification11,87.

The distinct histories of the upper and lower portions of the Amazon River have signatures in current biodiversity organisation, suggesting that the river has not been a single biogeographic barrier through time. The western Amazon River (Solimões) experienced several drainage reorganizations during the Neogene, as demonstrated by floodplain deposits forming extensive upland interfluves, whereas the eastern Amazon River is derived from an ancestral river that flowed eastward between the Guiana and Brazilian shields from the Cretaceous49. Thus, the variation of the strength of the riverine barrier effect over time was probably more relevant for the diversification of upland terra firme biota than was the dating of the onset of the transcontinental Amazon River. Biotic diversification suggests that changes in the strength of different portions of the Amazon River as a dispersal barrier occurred during the Pliocene and Pleistocene (Fig. 4).

Negro River basin

The Negro River flows over Precambrian rocks of the Guiana Shield and reaches the sedimentary substrates of the Solimões and Amazonas basins in its lower course. The wide valley of the lower Negro forms a fluvial ria. Sediment accumulation in the upstream sector of the ria has given birth to the Anavilhanas, one of the world’s largest and most complex fluvial archipelagos4,107 (Fig. 2). The Negro River’s pathway runs along the boundary between the Guiana Shield and soft sedimentary terrains of the Solimões sedimentary basin. The largest tributary of the Negro River is the Branco River, which drains the Tepuis mountains and the northern Brazilian savannahs107,108.

The lower Negro River shows evidence of incision during the Neogene9, with changes in the position of the main channel or tributaries109,110,111. During the Late Pleistocene and Holocene, changes in discharge and base level leading to sediment accumulation or incision phases promoted shifts in the extension and continuity of the lower Negro River’s seasonally flooded habitats (igapó) and archipelagos107,111,112. These changes affected the connectivity of populations associated with seasonally flooded habitats along the river85,113 and of terra firme forest populations in opposite margins114,115. For example, population genomic modelling indicates that the lower Negro ria became an effective barrier for floodplain specialist birds within the past 20,000 years85.

There is evidence for upland forest habitat establishment in the interfluve between the lower Negro and the Amazonas (Solimões) River since at least 3 Ma (ref. 9), coinciding with the historical effect of the Negro River as a barrier for terra firme forest birds and primate species and populations62,81,114,116,117,118 (Fig. 4). Phylogeographic and geological data corroborate the establishment of the Negro River’s lower course as a large river in the past 3 Ma (refs. 9,110) and the connection with the Branco River in the Late Pleistocene108. Together, these data highlight the effect of reorganization of the central Amazonian drainage system on biotic diversification during the Late Neogene and Pleistocene.

Madeira River basin

The Madeira River flows close to the boundary between the western sedimentary terrains and the higher-elevation terrains of the Brazilian Shield. It accounts for 15% of the Amazon River discharge and provides the largest portion of its suspended sediments4,119, which are crucial for building seasonally flooded habitats along the Amazon River in eastern Amazonia. The Madeira watershed drains the Madre de Dios, Solimões and Amazonas sedimentary basins, and has some eastern bedrock tributaries in the Brazilian Shield (Fig. 2). Its upper tributaries in the sub-Andean lowlands are characterized by avulsive channels shifting across a large wetland (Madre de Dios, Mamoré and Guaporé Rivers), probably reorganized during the past 4 Ma owing to the uplift of the Fitzcarrald Arch120. The upper and western portions of the Madeira watershed include alluvial rivers and most eastern tributaries are bedrock rivers. The western portion of the watershed, identified by the interfluve with the Purus River, corresponds to a mosaic of terraces with preserved fluvial depositional features. These suggest that larger floodplains were converted into uplands during the Pleistocene10,121,122, and that past connections between the Madeira and the Purus might have existed, influencing their lower portion’s discharge and effectiveness as barriers to upland taxa64.

Most diversification events associated with the Madeira River align with its dynamic Pleistocene history, with splits in terra firme forest bird and primate taxa currently isolated by the Madeira River dating to around 1 to 2 Ma62,81,118,123,124,125 (Fig. 4). Population genomic structure of upland forest bird and frog populations83,126,127 and the characterization of a hybrid zone within the Madeira–Tapajós interfluve suggest that tributary rearrangements have been controlling population connectivity in this region128. Genomic studies of other taxa with similar distribution patterns123,129,130,131 further reveal the importance of tributaries for the isolation of local populations.

Rodent populations associated with seasonally flooded forests along the mid and lower Madeira are genetically close to populations along the Purus River132, supporting the idea that both rivers have had connected or pervasive floodplains. Connectivity between floodplains could have been established through the Amazon River mainstem or through capture events in tributaries draining the Purus–Madeira water divide. There is also evidence of past isolation and late Pleistocene contact between bird populations from the várzeas of the Madeira and Amazon Rivers14,133. Fauna associated with aquatic environments, including caimans and river dolphins, show evidence of genetic discontinuities along the current main channel of the Madeira134,135. These studies further suggest late Pleistocene changes in connectivity both along the Madeira River and with the Purus and Amazon Rivers.

Western sedimentary basin rivers

Western Amazonian rivers, such as the Juruá, Purus, Japurá, Ucayali and Marañón, flow over Pleistocene alluvial terrains6 (Fig. 2), are susceptible to incision and aggradation, and show more frequent lateral channel migration and avulsion compared to bedrock eastern rivers. During the Pleistocene, the interfluves of western Amazonian rivers went through substantial variations in the relative extent of their floodplains and uplands (terra firme). The uppermost terrace surfaces document a major base-level fall leading to a decrease in floodplains and expansion of non-flooded forest areas between 100,000 and 40,000 years ago6, affecting the watersheds of the Juruá, Purus and western Madeira rivers136. There is also evidence of changes in the course of large rivers mainstems draining alluvial terrains, including a Late Pleistocene shift of the lower Juruá River into its modern position137 and a large avulsion of the Ucayali River138. Although these channel shifts are spatially limited, their recurrence through time can lead to cumulative large-scale changes in the distribution of uplands (supporting terra firme forest) bounded by floodplains (hosting seasonally flooded habitats).

Morphological and genetic variation in terra firme forest taxa reveal only a few examples of diversification events associated with western Amazonian rivers (Fig. 4). This limited variation may be related to their dynamism as alluvial rivers, which promote frequent changes in the spatial distribution and connectivity of alluvial uplands (fluvial terraces). This landscape dynamic implies the formation of permeable and short-duration barriers through time46. For example, most species documented in an area that moved to the opposite side of the Ucayali River (owing to an avulsion in the eighteenth century) matched taxa on their current river side, and not on the opposite side, pending detailed genetic analyses for investigating past hybridization138. However, large sampling gaps still hinder a better understanding of the role of these rivers as barriers to dispersal. Detailed terra firme bird inventories in opposite margins of the Juruá River, for example, have found several taxa with distributions delimited by the main channel and bounding floodplains65.

Although important for shaping seasonally flooded environments, channel meandering within the floodplains due to lateral shifts often has minor effects on the connectivity of terra firme taxa because they remain isolated on opposite margins by the channel belt–floodplain complex. This isolation might explain some early Pleistocene diversification events associated with dynamic rivers flowing over alluvial terrains, such as the Japurá, Ucayali and Purus36,124,126,139,140 (Fig. 4). The Late Pleistocene retraction of floodplains in western Amazonia and the expansion of terra firme habitats over abandoned floodplains6 probably constrained the current distributional limits of species from these areas and could explain the observed instances of introgression involving taxa from small western Amazonian interfluves141,142,143.

Shield rivers

Large eastern Amazonian rivers, such as the Tapajós, Xingu and Tocantins, drain the Brazilian Shield and have low sediment load and clear water (Fig. 2, Box 2). Rivers draining the Guiana Shield also have clear water, but have smaller watersheds than do Brazilian Shield rivers. Amazonian shield rivers have rapids and narrow floodplains and have been historically more stable than other Amazonian rivers because most of their watersheds flow over Precambrian bedrocks with higher resistance to erosion. However, some sections of these rivers flow over diverse geological terrains, with headwaters draining Cretaceous–Cenozoic soft sedimentary terrains in the central Brazilian savannah. These upper sections are more susceptible to lateral channel migration than lower sections (Fig. 2). The lowermost reaches of the Xingu and Tapajós are fluvial rias144,145, similar to the downstream reach of the Negro River, with wide channels (100–150 km in length and 10–20 km in width) incised in soft Cretaceous–Cenozoic sedimentary rocks of the Amazonas and Marajó sedimentary basins (Fig. 2). The lower Tocantins is characterized by a wide estuary currently disconnected from the Amazon River mainstem (Fig. 2). Thus, the Tapajós, Xingu and Tocantins watersheds sustain different riverine landscapes compared to western Amazonian rivers. Similar characteristics occur in rivers draining the Guiana Shield, such as the Trombetas and the Paru rivers. The shield rivers also have a smaller influence on the spatial distribution of habitats in their adjacent uplands than do the western alluvial rivers, whose floodplains can expand over upland areas. Hence, shield areas can act as geomorphological refugia for terra firme upland habitats during phases of fluvial aggradation and floodplain expansion. However, although less susceptible to landscape changes caused by river meandering, the eastern uplands over the Guiana and Brazilian shields may be subject to changes in vegetation structure, driven by climate change in eastern Amazonia73,81.

Surveys of birds, reptiles and frogs on opposite margins of the Tapajós indicate that the river is the main factor structuring biological communities from the upland terra firme forest146,147,148. However, on average, Brazilian Shield rivers are associated with more recent diversification events when compared to the Amazon, Negro and Madeira rivers62,81,125,149 (Fig. 4). This pattern is corroborated by the few existing studies with dense sampling in frogs150,151.

Brazilian Shield rivers have headwaters in central Brazil, where precipitation is susceptible to the hydrological effects of climate change72,73. Thus, their aquatic and seasonally flooded habitats are sensitive to droughts, potentially reducing their strength as barriers to the dispersal of terra firme forest taxa. This effect is most pronounced in the smaller drainages of the upper courses, where gene flow and introgression have been detected80,81,152,153. Pleistocene climate changes led to a stronger reduction in precipitation in southeastern Amazonia72,73 in comparison to western Amazonia, both reducing the effectiveness of shield rivers as barriers to upland species dispersal and promoting local extinctions, which in turn could have permitted recolonization from adjacent interfluves81.

The lower portions of Brazilian Shield rivers cross the Amazonas sedimentary basin before reaching the Amazon River main trunk. Sediment deposition ages obtained in lower elevation terraces bounding the Amazon River indicate that there have been important phases of incision during the Pleistocene, leading to the abandonment of floodplains and the formation of new areas covered by terra firme forest10. The expansion of uplands bounding the Amazon River and the lower Xingu and Tapajós rivers might have promoted a reorganization of distribution patterns for species specialized in terra firme forests, with potential contact among populations from the opposite margins of these large rivers81,124,128.

The barrier strength of shield rivers responds to a more restricted set of variables when compared to alluvial rivers draining soft sedimentary terrains. Their discharge and the width of their floodplain belts rely mostly on the hydroclimate, with a reduced influence of autogenic sedimentary dynamics compared to western Amazonian alluvial rivers. However, their lower portions can be influenced by changes in the trunk river, affecting connectivity among populations occurring in adjacent interfluvial areas. Similar behaviour is expected for rivers draining the Guiana Shield, which are still poorly studied in terms of sedimentary and palaeoclimate changes.

Spatially heterogeneous threats

Rivers are major drivers of environmental heterogeneity and landscape changes in Amazonia over time. The geography and chronology of Amazonian biotic diversification are in contrast with theories proposing long-standing landscape stability following the establishment of the transcontinental Amazon River, presumably in the Neogene51. Geological and genomic evidence indicate marked changes in drainage configuration and the distribution of upland and seasonally flooded habitats during the Quaternary (2.58 Ma to present). The evidence reviewed above indicates a major division of Amazonia in terms of fluvial landscape dynamics and history. The landscape of the western alluvial region, west of the Negro and Madeira rivers, is widely reshaped by rivers over a timespan of tens to hundreds of thousands of years. This reshaping occurs through frequent incision and aggradation phases, as well as channel capture and avulsion over soft sedimentary terrains, leading to the expansion (connectivity) or reduction (fragmentation) of upland terra firme habitats, contrasting with the eastward plateau areas that have harder terrain (for example, the Precambrian rocks of the Guiana and Brazilian shields), and where river valleys experience long-term widening and have narrow, confined floodplains.

Amazonian rivers differ in their historical and current vulnerability to precipitation changes. The Solimões–Amazon mainstem has catchment areas spanning both hemispheres, and the Madeira and Negro rivers feature catchments in high-precipitation areas in the Andes. Consequentially, these rivers would be historically the most resilient within Amazonia to changes in moisture distribution by the South American monsoon, and therefore less vulnerable to discharge variation owing to extreme climate events. By contrast, eastern rivers draining the Brazilian Shield, owing to their dependence on precipitation from the central Brazil savannah (the Cerrado)154, were probably the most vulnerable to past climate changes, affecting their historical roles as barriers to biotic dispersal81. Amazonian rivers over the Brazilian Shield are also currently more vulnerable to discharge reductions due to the combined effects of deforestation155 and extreme dry seasons caused by anthropogenic climate change156.

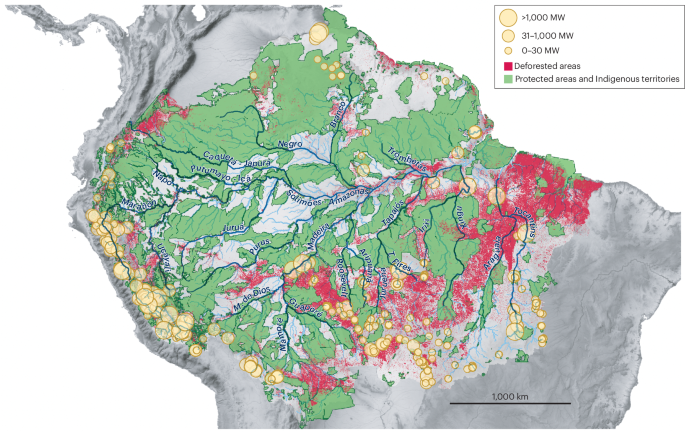

The combined effects of landscape dynamism and the conditions for resilience of populations in a highly productive and vast environment have contributed to the currently observed patterns of high species richness in Amazonia. However, combined anthropogenic effects19,157 concentrated in some interfluves pose threats to the maintenance of these conditions15,17,25. Various factors, including riverine barriers, endemism patterns and diversification history, often with ecologically similar species occupying adjacent interfluves, hinder population access to areas not affected by deforestation and/or more resilient to climate change. This dispersal restriction further enhances the importance of considering biogeographic patterns in extinction risk assessments (Fig. 5). Additionally, populations at interfluves with reduced hydroclimatic resilience in southeastern Amazonia can carry genetic signatures of population bottlenecks and lower genetic diversity. It is unclear whether an unstable demographic past will improve the resilience of a population to current anthropogenic effects through pre-existing adaptations or will aggravate it owing to lower genetic diversity. Thus, the genomic characterization of populations is important in determining their conservation status and for improving impact-assessment reports.

Green areas indicate protected areas and Indigenous territories. Red areas indicate regions affected by deforestation. Yellow circles correspond to operational hydropower dams and are sized according to their installed capacity in megawatts (MW). Hydropower dam data are for the year 2020. Amazonian interfluves are heterogeneous in both the degree to which they are affected by deforestation and to which they are covered by protected areas and Indigenous territories. Data for hydropower dams, deforestation and protected areas are from the RAISG Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information.

The annual cycle of flooding is essential for the functioning of Amazonian ecosystems. Seasonally flooded habitats have unique biodiversity and provide resources for terra firme forest populations during the dry season158,159. The effects of hydropower dams on the sedimentary budget and hydrology of rivers are cumulative and far-reaching, disrupting the natural flooding cycle and the ecological processes dependent on it. The construction of hydropower dams also contributes indirectly to other threats on ecosystems, such as regional deforestation160 and the suppression of large stretches of seasonally flooded habitats18, which are often not evaluated in impact-assessment studies for Amazonian dams161. Seasonally flooded habitats are also especially vulnerable because they take a long time to recover from fires, and their vulnerability might increase because climate change is expected to increase the frequency and intensity of droughts in eastern Amazonia, during which fires are more likely to occur162. Seasonally flooded habitats are therefore severely threatened under the current development model imposed on Amazonia. The evolution of taxa in seasonally flooded habitats is coupled with hydrological connectivity and riverine habitat availability11,87; the collapse of these habitats has the potential to affect not only large downstream portions of the basin, but also ecological processes, such as seasonal food resources159, that sustain the neighbouring terra firme forest, driving whole ecosystem degradation.

Many Amazonian Indigenous peoples and local communities depend on Amazonian rivers for the maintenance of their cultural traditions, their food resources and their survival163. Large hydropower dams have had devastating consequences for these communities, including the Santo Antônio and Jirau dams in the Madeira River (operation started in 2012), and the dams of the Belo Monte hydropower plant in the Xingu River (operation started in 2016, with full operation in 2019). These dams have disrupted flooding cycles in long stretches of seasonally flooded forests. The resultant ecological impacts in aquatic and seasonally flooded ecosystems are ongoing161,163,164. The construction of these sizeable Amazonian dams are dangerous large-scale experiments, because ecosystem functioning and biodiversity patterns are not well enough understood to assess the effects of these disruptions, even over short prospective timescales. It is clear, in part based on evidence collected by the Indigenous peoples and local communities affected163,165, that ecosystems are decaying rapidly, and that the natural resources needed for their subsistence are quickly becoming unavailable.

The combined effects of deforestation, fire, river impoundment and climate change are quickly shifting the long-lasting conditions that have promoted the evolution and maintenance of Amazonia’s high biodiversity17. The rate of change driven by anthropogenic impacts is much higher than that of historical landscape evolution13, and our understanding of the consequences is still emerging.

Summary and future directions

Besides biotic distribution patterns delimited by large rivers, the phylogeny of several Amazonian clades reveal nodes that can be related to current riverine barriers, most of them dated to the Pliocene and Pleistocene2,16,91,114. Variability in the node ages related to each riverine barrier suggests that landscape changes over multiple spatiotemporal scales have affected connectivity in different ways in distinct taxa. Thus, generalized congruence seems improbable, which does not mean that riverine evolution has not affected biotic diversification15,88.

Combining ecological and historical information is essential to formulating meaningful hypotheses that could help us to understand the many drivers of diversification and the factors that enable the maintenance of the highly diverse ecosystems that comprise Amazonia. Future methodological approaches should incorporate the heterogeneous nature of both Amazonia and the species–habitat associations within it. An interdisciplinary approach should be targeted, incorporating Earth and life sciences from its inception, and more geographically focused, thanks to the heterogeneity of Amazonia. Geogenomic approaches combine geological and genomic data100,166,167, but require extensive pre-existing knowledge, including data on landscape history, species distributions, taxonomy, habitat association and diversification patterns. Given the vastness of Amazonia, this information is scarce (Boxes 1 and 2) but is becoming more available. Continued field research, establishment and maintenance of local biological collections, accumulation of genomic data, and the sampling of targets for climatic and physical landscape reconstructions are essential to improving geogenomic approaches within Amazonia. An understanding of the associations between species and specific habitats, as well as the ecological processes that drive species occurrence and abundance are both critically important. Insights can be generated through standardized sampling across the basin168, and through partnerships with Indigenous peoples and local communities, who hold profound knowledge about the ecological processes and have developed ways of life that preserve these processes24,169,170.

In modern-day Amazonia, the study of biogeography could connect our understanding of past landscape change, current diversity patterns, threats and potential future scenarios. Increasing and integrating this knowledge, and making it available for decision-makers, especially regional governments and Indigenous peoples and local communities managing their own territories, is essential to both understanding and protecting the region. The ecological and social costs of infrastructure development in Amazonia need to be addressed in an integrative context, considering multicultural and interdisciplinary insights. Impact assessments involving Amazonian rivers should include a detailed evaluation of consequences to distinct ecosystems, biotic interactions and local human populations, both upstream and downstream17,18. These assessments are currently hindered by lack of knowledge about biodiversity patterns and ecological processes on a basin scale. Therefore, infrastructure development involving and affecting Amazonian rivers should be avoided.

Responses