The spinal cord injury (SCI) peer support evaluation tool: the development of a tool to assess outcomes of peer support programs within SCI community-based organizations

Introduction

Over 86,000 individuals in Canada have a spinal cord injury (SCI), with approximately 4000 new cases per annum [1]. Long-term health complications of a SCI (e.g., pressure injuries) place strain on the healthcare system and public/government services as impaired physical functioning can complicate obtaining or returning to employment [2]. The complex interaction of secondary health conditions and physical impairment associated with SCI can also alter social relationships and social participation opportunities [3,4,5]. These challenges contribute to the estimated $2.67 billion annual economic investment associated with SCI [6].

Programs and public services that help individuals with SCI manage and overcome the challenges of living with SCI play an important role in improving quality of life and reducing the strain on public health care and government services. Peer support programs are a widely available service in Canada, defined by our team as a peer interaction that aims to help individuals who share similar lived experiences adapt and/or thrive. Peer support programs offered by Canadian community-based organizations primarily adopt a discussion-based approach by facilitating one-on-one or group discussions between individuals with SCI [7]. Peer support has the potential to improve overall well-being and quality of life of people with SCI [8]. While peer support is recognized as an important service across Canada [7], it currently lacks high quality evidence of its effectiveness [7, 8]. This lack of evidence is partly attributable to the difficulties in aggregating data from different SCI peer support programs [7] due to inconsistent outcome reporting and variation of measurement instruments [8], as well as different focuses of the programs [7]. The difficulty in evaluating peer support programs delivered by community-based organizations is particularly relevant for Canadian SCI research. Research-based trials are difficult to implement in Canadian community settings, making the synthesis of data from community SCI peer support programs important for assessing evidence of effectiveness.

Development of a SCI peer support specific outcome measurement instrument (OMI; defined as a tool to measure quality or quantity of outcomes) [9] using a core outcome set would benefit SCI researchers and community program providers. A core outcome set is defined as a set of important outcomes, agreed upon by consensus, that should be measured to evaluate the effectiveness of programs for a specific population (e.g., persons with SCI) and context (e.g., peer support) [10]. No universal SCI peer support measure or core outcome set currently exists. There is therefore an inherent need to develop a SCI peer support OMI. This OMI can therefore help (1) researchers, (2) community organizations, and (3) partnership between researchers and community organizations to collect data using consistent outcome measures, that can be compared and aggregated across studies to determine the effectiveness of SCI peer support programs. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop and test a spinal cord injury (SCI) peer support evaluation tool by following and adapting the COSMIN guideline for community-based settings.

Methods

Design

This study used and adapted the four-step process to select core outcomes set by the Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative and the Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) initiative [9]. The four-step process has been used to develop OMIs for various disability groups [11] and for programs occurring in community settings [12]. Importantly, according to the COSMIN guideline, OMIs are not homogenous in their structure and can include various measurement approaches (e.g., single item measures, questionnaires, a score obtained through physical examination, a laboratory measurement, etc.) [9]. These steps allowed for a methodological process to identify and select outcomes that would be important for a community-based evaluation tool for SCI peer support programs. Appropriate methodologies were used for each step: Delphi consensus, measurement literature review, quality rating and community consensus methods, think-aloud, and test-retest. Ethic certificates were obtained for steps where participant data collection was conducted (McGill REB file #: 21-11-011). Participants provided informed consent before data collection.

This work was conducted by a community-university partnership. We used the integrated knowledge translation guiding principles for SCI research to guide this partnership [13]. The roles of each team member across research phases are presented in Supplemental 1.

Procedures

Step 1. Conceptual considerations

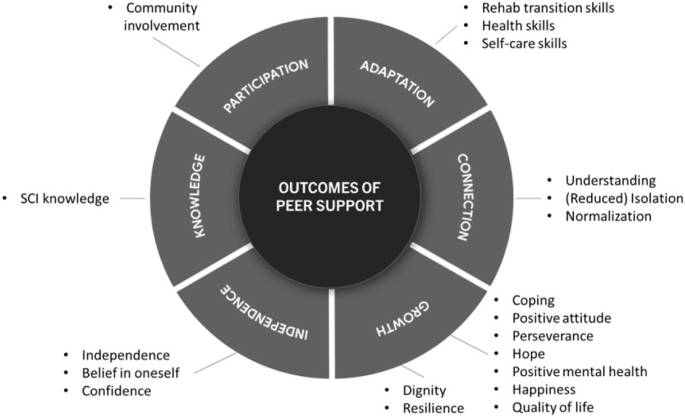

Prior to selecting outcomes of SCI peer support programs delivered by community-based organizations, an understanding of the relevant outcomes to this context was needed. Published in two separate papers, our group identified 87 outcomes relevant to SCI peer support through meta-synthesis and a qualitative study among peer support users [14, 15] (87 outcomes were listed in Supplemental 6). The peer support outcome model developed from the meta-synthesis also guided this study to ensure that each category was represented by at least one outcome (Fig. 1). We conducted two Delphi consensus studies among peer support users (Delphi 1) and peer support program coordinators and directors (Delphi 2) to identify the most important outcomes for SCI peer support. Detailed information on the Delphi methodology is available in our previous publication [16].

Note. Figure adapted from Rocchi et al. [14], reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com).

Step 2. Finding existing outcome measurement instruments

To reduce burden on peer support users/peer mentees who will be completing the core outcome set (hereafter referred to as the SCI Peer Support Evaluation tool), our partnership decided to use a single-item measure for each outcome. This decision aligns with a recent call for single-item measures in time-restricted conditions to facilitate response and to reduce data-processing costs [17], which are important for community-based organizations. Regarding outcomes identified in Step 1, online databases (e.g., Neuro-QOL, NIH Toolbox, PROMIS, ASCQ-Me, PsychINFO, MEDline) were individually searched by two researchers (ZS, OP) for validated single-item and multi-item measures for each outcome (see Supplemental 2). ZS and SS searched and identified items that related to the outcomes from surveys of our partnered community-based organizations. For each outcome, ZS and OP each selected validated multi-item and single-item measures that aligned with the outcome definitions. Outcome definitions were informed by the data from the meta-synthesis [14].

Step 3. Quality assessment of outcome measurement instruments

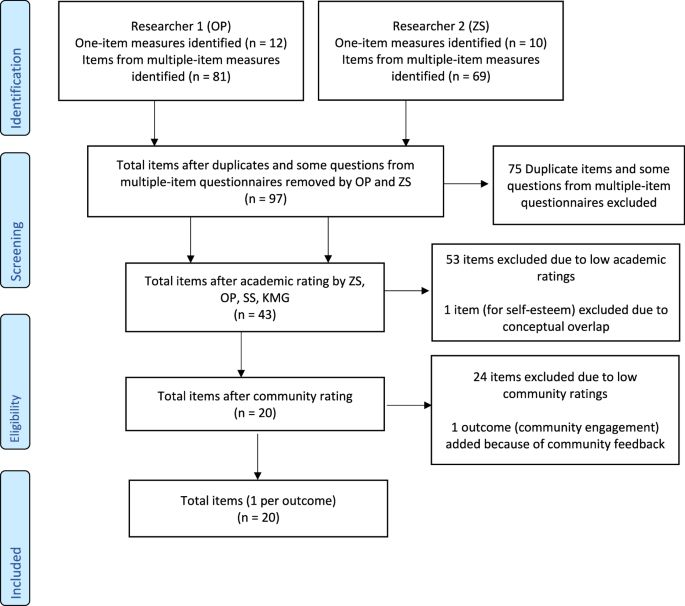

Four researchers (SS, KMG, OP, ZS) separately reviewed and rated the 97 items based on the conceptual alignment with the respective outcomes and their definitions, using a four-point scale ranging from 0 (Does not match the definition) to 3 (Greatly matches the definition). When multiple items were rated as “3” for the same outcome, the researchers indicated with an asterisk the item they felt was the best conceptual match. The four researchers then summed the rating scores and met to select the top two items for each outcome. Next, four community-based partners (CM, TC, HF, SC) and two researcher partners (HG, VN) used the same scale and procedures to rate the remaining items. The item that received the highest sum score was kept for each outcome. There were instances when the items received the same sum score for one outcome or there were inconsistent ratings across the team members (CM, TC, HF, SC, HG, VN). The team had two online meetings to discuss and decide on best matches of items to outcomes. The team also identified potential outcomes that were conceptually overlapping or not relevant. As a result, the team removed any overlapping item(s) and made minor modifications to the wording to fit the goal of the SCI Peer Support Evaluation Tool (see Fig. 2 for flow chart). Through the team meetings and follow-up email exchanges, we created a preliminary version of the SCI Peer Support Evaluation Tool consisting of the remaining outcomes and items.

PRISMA-inspired flow chart for item Identification.

Step 4. Generic recommendations on the selection of outcome measurement instruments

We consulted with Executive Directors/Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) and Peer Support Program Coordinators from ten Canadian provincial community-based SCI organizations to discuss the preliminary version of the SCI Peer Support Evaluation Tool. The Directors/CEOs and Coordinators provided feedback, via an online survey, on the relevancy, appropriateness of language use, clarity, specificity/unambiguity, and unintended adverse effects of each item [Supplemental 3]. They also participated in a 2-h online consultation meeting. To modify any item(s) that received a lower rating, participants discussed in breakout rooms and large group discussions. Our team then met to modify the items for each outcome to ensure content validity.

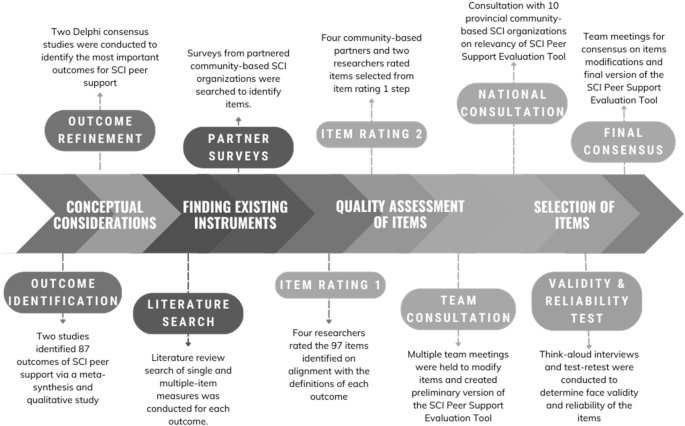

Next, we assessed the response face validity and test-retest reliability of the evaluation tool items based on recent recommendations [17]. For face validity, we used a think-aloud method [18] and for test-retest reliability, we used a 10-day recall testing period. Adults with SCI who received peer support from the partnered community-based SCI organizations were recruited (SCI BC, SCI Saskatchewan, SCI Ontario, Ability New Brunswick). Participants first responded to the items with a researcher present on an online meeting. The researcher prompted participants to voice their thoughts to capture their understanding and approach to answering each item. Once participants answered all the questions, they were asked to reflect on the process of responding to the evaluation tool and provide feedback [Supplemental 4: think-aloud interview guide]. Ten days later, participants were asked to complete the evaluation tool again without thinking aloud. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed. Participants’ utterances for each item from the interviews were pulled from the transcripts. Six researchers (including two people with SCI who were also peer supporters/mentors) (a) rated the correspondence between participants’ responses and outcome definitions, (b) in smaller groups, discussed the main issues (e.g., clarity) and suggested changes for the items with poor correspondence ratings, and (c) met as a larger group to reach consensus on suggested changes prior to bringing forward to the partnership. Reliability of the participants’ responses at two time points was tested using interclass correlation coefficient (ICCs). See Fig. 3 for overview of SCI Peer Support Evaluation development procedures.

SCI peer support evaluation tool development procedures.

Results

Step 1. Conceptual considerations

The Delphi studies identified 21 outcomes rated as very important or “one of the most important” for SCI peer support programs. The ratings of each outcome can be found in our previous publication [16].

Step 2. Finding existing outcome measurement instruments

The online database and community document search yielded a total of 22 single-item measures related to the 21 outcomes identified in Step 1. An additional 150 items from validated multiple-item measures were identified, totaling 172 single item questions. After duplicates and some questions from multiple-item questionnaires were removed (n = 75) a total of 97 items remained. During this process, a 22nd outcome was identified (community engagement) and added to the list due to its meaningfulness to the community-based organizations and alignment with the peer support outcome model [14]. Supplemental 5 provides a breakdown of single-and multiple-item measures identified per outcome.

Step 3. Quality assessment of outcome measurement instruments

Supplemental 6 outlined the 97 items identified in Step 2 and the decisions on retention/removal of each item. During this process, the team agreed on the final 20 outcomes that aligned with our broad conceptualization of peer support outcomes (see Fig. 1) and its respective items. During two partnership meetings, we agreed on using a neutral statement (i.e., “Thinking about my experience with [the peer support program]”) as the stem/preamble for the evaluation tool. Given semantic and agreement scales do not appear to cause more response bias [19] and semantic scales are often referred to item-specific evaluations [20], we also decided to use semantic differential scales with two antonyms at each end of the 5-option scale for the items (e.g., Thinking about my experience with [the peer support program], I feel _____ in my experience with my spinal cord injury/disability: (1) a lot less alone, (2) less alone, (3) as alone as before, (4) more alone, (5) a lot more alone).

Step 4. Generic recommendations on the selection of outcome measurement instruments

Through consultation with provincial community-based SCI organizations, nine Executive Directors/CEOs and Peer Support Program Coordinators provided feedback (Table 1). All items reached consensus as they received an average rating above 5 out of 7 for relevancy, language appropriateness, clarity, and specificity (Supplemental 7). In the consensus meeting, participants discussed and revised items that may lead to unintended/adverse effects through ratings or comments. For example, we changed the item for Dignity from “My life has _____ value.” To “I feel my sense of self-worth is ______.” due to the low rating and participants’ comments. All modifications were summarized in Supplemental 6.

Face validity was very good as per participants’ comments during the think aloud interviews. Participants found the items easy to understand and relevant to their peer support experiences. For example, when answering the item for SCI Knowledge, one participant said: “I think I learned a great deal, actually, she [mentor] told me a lot about her experiences with certain things, like sexuality and things like that”. Based on similar responses, no modifications were needed for 14 items. Based on participants’ responses, we deemed wording changes were required for items related to: understanding/feeling understood, normalization, rehabilitation transition skills, dignity, resilience, and coping. For example, when answering the item for Understanding/feeling understood, one participant stated: “I wasn’t sure who the people were that the question referred to. Is it the people in the peer program or people outside of SCI? I didn’t really know”. According to their comment, we changed the item from “I feel there are some people who understand me _____” to “I feel _____ understood”. In examining reliability, the ICC between the test-retest across items ranged between 0.32 and 0.89. However, after identifying and removing outlier scores (n =1 to 2 participants for 7 outcomes), ICCs ranged between 0.61 and 0.89 (Supplemental 8), representing an acceptable test-retest reliability. Some of the low ICCs were related to outcomes requiring wording changes (e.g., confidence and belief in oneself).

The research team then created first iterations of changes to the 6 items and presented the changes to the larger partnership in two consensus meetings and a final voting consensus exercise. After these consensus meetings, modifications to the normalization, coping, dignity, and resilience items consisted of minor wording changes for clarity purposes (see Supplemental 8). For the understanding and rehabilitation transition skill outcomes, the items were modified to improve clarity on the intent of the item and enhance the alignment with the outcome (see Supplemental 8). To focus participants’ attention on peer support, we included the stem for each item in the final version. To help participants recall their whole peer support experience, an introductory text was added upon peer review and was approved by the full partnership. This final version, consisting of single items for 20 outcomes, was approved by the full partnership team as having evidence to support its content validity in SCI (Table 2).

Discussion

The SCI Peer Support Evaluation Tool fills an important gap in the current SCI peer support literature and practice. For one, there have been issues in comparing the impact of programs within and across organizations due to the difficulties in aggregating data from different SCI peer support programs [7]. This tool provides valid and reliable single-item measures of 20 outcomes that will improve consistency in evaluating SCI peer support programs within (e.g., virtual vs in-person peer support programs) and across organizations in Canada. Similarly, the tool should help reduce the inconsistency of outcome reporting and variation of measurement instruments across the international SCI peer support literature [8]. The single-item approach facilitates the evaluation of peer support programs delivered by community-based organizations or researchers by having easy to use items. The single items can be used independently as only outcomes that align with goals of peer support programs can be selected. The development of the SCI Peer Support Evaluation Tool extends the COS and OMI development literature for persons with disabilities [21] or chronic diseases [22]. This study provides an example of how to develop a COS and OMI by utilizing the research, SCI lived experience, and community programming expertise of partnership members while following the IKT guiding principles (as outlined in Fig. 3 and Supplemental 1).

An IKT approach enabled us to adopt a pragmatic research paradigm that focuses on solving practical problems [23, 24]. We engaged the individuals involved in peer support programs (organization staff, peer supporter/mentors, peer mentees, etc.) at different stages by utilizing IKT partnership strategies [25]. In reflection, strategies “co-writing grant”, “listening to each other”, “engaging persons with SCI” were of particular importance because they maximized opportunities to share decision-making and expertise. Despite the use of these strategies, the length of time to complete this research was longer than expected, requiring us to cope with challenges in losing and onboarding community partners. As partnership research becomes more common, equipping partnerships on how to manage attrition and on-boarding will be important.

From a practical standpoint, evaluating SCI Peer Support programs using this tool will help identify the strongest and weakest part of a program. Such evaluation may guide community-based organizations on how to optimize SCI peer support delivery. The evaluation tool can also support funding applications by providing evidence-based data on the impact of SCI peer support, to support the sustainability of these programs. While an advantage of the tool is that it can measure 20 different outcomes, we appreciate that not all evaluations will require assessments of all 20 outcomes. A benefit of the SCI Peer Support Evaluation Tool is that community-based organizations or researchers aiming to evaluate a peer support program can have the flexibility to select the items that corresponds to outcomes of the tested peer support program, meaning not all 20 items needed to be added in program evaluation efforts. We therefore encourage evaluators to select the items that are most relevant to their research/program evaluation questions and to administer them without additional modifications. These steps will help to ensure consistent, valid, comparable assessments across studies/evaluations. The tool therefore provides a key starting point to assess these 20 identified outcomes of peer support. It does not preclude organizations and programs to assess other outcomes that may be specific to their peer support program such as wheelchair skills or self-management [26].

Despite the benefits of this SCI Peer Support Evaluation Tool, we cannot assume that this tool will automatically be implemented within community-based organizations. Community-based organizations highlighted in our meetings and in past research [7] that they often do not have the knowledge or expertise to use measurement or evaluation tools. However, evidence-based resources are more likely to be adopted by target users if implementation tools are created [27, 28]. Our team is concurrently developing a toolkit to support the implementation of the SCI Peer Support Evaluation Tool. This toolkit will help users to set-up an internal process to identify and select the outcomes and items that are most relevant with their program (visit www.mcgill.ca/scipm for resources). It will also provide decision-making aids for administrating the tool, managing the data, and interpreting the results. Such approaches should then facilitate the use and ultimately lead to greater evaluation of SCI peer support program for SCI community-based organizations.

We acknowledge that single-item measures have their limitations. From a psychometric perspective, multiple items provide better estimates of reliability and capture more information on the social, cognitive, or emotions factors of human experiences [17]. However, community-based organizations have little resources for research-level evaluations, and their evaluations cannot cause high assessment burden to their members. Indeed, it would be nearly impossible, in the SCI peer support context, to assess 20 different outcomes using standard, research-level measures [7, 14]. Using single-item measures is therefore a method to counter participant burden within community contexts [17]. The SCI Peer Support Evaluation Tool provides an evidence-based resource to measure key outcomes within peer support programs delivered by SCI community-based organizations.

Assessing a variety of outcomes with single items, community-based organizations and researchers may better capture the complexity of SCI peer support. In our previous research, we measured only a few outcomes and we concluded that the results did not necessarily reflect the breadth or depth of impact of peer support [29,30,31]. Assessing multiple outcomes, while minimizing participant burden, might help to elucidate the impact of peer support.

Study limitations

We recognize that convergent or predictive validity was not assessed, but rather focused on face validity through a think aloud survey [17]. There is now an opportunity to revisit the psychometrics of this tool once it is implemented and used in the community context to examine other dimensions of validity and reliability with a larger sample. These future studies could also examine the relationship and interplay between these outcomes whereby identifying whether peer support has direct or indirect impacts on certain outcomes. Finally, the development of this evaluation tool was conducted in a community-based Canadian context. We acknowledge that SCI peer support programs in Canada primarily adopt a discussion-based approach, while alternative approaches (e.g., activity-based) are also used in and outside Canada. Due to the differences in peer support programs, different outcomes may be identified as important in other contexts. The decision to focus on the Canadian community-based organizations was driven by the goal to address the unique practical need of these organizations in assessing the impact of their programs. Gathering perspectives from individuals involved in diverse peer support programs beyond the Canadian context could offer unique insights in future research. However, given the rigorous approach to develop items for each outcome, the potential for international usage of this evaluation tool remains high. Further validation and refinement of the tool (e.g., updated definition based on international consensus on a peer support taxonomy) with input from a diverse, international perspective would increase its usage beyond the Canadian context.

Conclusion

The SCI Peer Support Evaluation Tool provides an important and practical resource to facilitate the assessment and evaluation of the complex nature of SCI peer support. The implementation of this tool should facilitate the optimization of peer support programs for people with SCI in Canada, and hopefully serve useful for other international contexts.

Responses