The supply and quality of STEM teachers

Literature review

In this paper, I rely on two theories to inform my approach and analyses: the economic labor market theory of supply and demand and the educational production function. The first theory provides the framework to examine the production of STEM teachers while the second theory explains the importance of STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications.

Using the economic labor market theory of supply and demand, Guarino et al. (2006) put forward a conceptual framework that posits the number of laborers in a specific occupation (i.e., the number of teachers) is the point at which the supply of available labor equals the demand for that labor. In its most basic terms, the economic equilibrium stipulates supply and demand for workers fluctuate based on the value assigned to the position. Within highly valued positions, there will be a surplus of labor, as more individuals will be seeking to enter that field. When positions are of low value, there will be a shortfall of labor, as fewer individuals will be seeking to enter the field. Applied to the labor market for teachers, individuals value certain teaching positions based on a variety of characteristics, including institutional characteristics, economic conditions, and feelings of fulfillment and personal satisfaction from the position (e.g., Zabalza 1987). While feelings of fulfillment and personal satisfaction are not available for analysis, there are several measures of institutional characteristics and economic conditions that can be leveraged to examine the production of STEM teachers. In particular, we can observe the sector and type of institution that produces STEM teachers, state gross domestic product (GDP), revenue progressivity, property tax, unemployment rate, average teacher salary, cost-of-living adjustment, and per-pupil-expenditure. These measures allow us to examine how institutional characteristics and economic indicators are associated with the production of STEM teachers. In sum, this conceptual framework is the foundation of this work to examine changes in STEM teacher production.

The other framework that informs this work is the education production function stating that the measure of school output, such as student learning or achievement, is a function of three main categories, school characteristics, environmental influences, and student characteristics, including ability and initial knowledge (Bowles 1970). While all three categories play influential roles in how much students learn or achieve, educators are most interested in the first category, school-based factors, since they have the most direct influence in these factors than the other two categories. After decades of research, the evidence suggests that teachers are the single most important school-based factor of student achievement (e.g., Chetty et al. 2014; Rivkin et al. 2005). As a result, educators and policymakers have spent substantial time and investment to ensure classrooms are staffed with qualified teachers (Hanushek et al. 2004; Ingersoll and Smith 2003) and to address the uneven distribution of the quantity and quality of teachers, particularly for traditionally disadvantaged students (Feng and Sass 2017; Lankford et al. 2002). Educators are then concerned, not only with the qualifications of teachers but also with who is teaching students, particularly in STEM disciplines since teacher demographics have direct implications on student achievement and aspirations (e.g., Makarova et al. 2019; Redding 2019). Towards this end, we care about STEM teacher demographics (i.e., gender, race/ethnicity) and qualifications (e.g., certification, graduate degree, and STEM qualification) as well as how these characteristics may differ by school status (i.e., higher-poverty schools, racially minoritized schools). To sum up, the education production function informs the analysis of STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications.

When we bring these two theories together, we observe that the economic labor market theory of supply and demand aligns closely with the education production function. In particular, the economic labor market theory of supply and demand would suggest that, if the STEM teacher supply is not sufficient to meet demands, then schools may face limited hiring options. All else equal, this may then lead to schools and districts hiring uncertified teachers and teachers teaching out of the field to meet demands. This suggests a reduction in teacher quality, which would then negatively impact student learning as well as their STEM aspirations. Overall, the integration of these two theories forms the basis of my perspective and analyses.

Changes in the teacher labor market

From the late 1980s to the early 2010s, the number of science and math teachers in the U.S. has increased by about 90% over time (Ingersoll and Merrill 2017). While this growth seems sufficient, there are causes for concern as the teacher supply changed in the last decade. Since 2009, the number of teacher candidates, those who have completed courses in a teacher preparation program (TPP) and taken in-state certification exams, has dropped 30 percent (Saenz-Armstrong 2023). During this time, STEM teacher shortages are reported by most states every year (Dee and Goldhaber, 2017; United States Department of Education, n.d.). Recent works suggest the teacher shortage, including in STEM fields, is large and growing (García and Weiss 2019; Nguyen et al. 2022). Moreover, schools and districts report difficulty in filling STEM positions three to four times more frequently than they do for other positions (Dee and Goldhaber 2017; Goldhaber et al. 2022). While it is currently unknown how the COVID-19 pandemic ultimately affected STEM teacher supply, the most current national and state surveys indicate many more teachers are thinking of leaving the profession altogether, particularly in economically disadvantaged or racially minoritized schools (Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond 2017; Steiner and Woo 2021). Additionally, there have been significant increases in the reports of teacher shortages, particularly STEM teachers, since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (Goldhaber et al. 2022). In sum, while there is evidence suggesting that the production of teachers may be decreasing in the last ten years, it is unknown the extent to which this also applies to STEM teachers, and at the same time, the need to increase STEM graduates is only increasing over time and the STEM teacher shortages appear to be growing.

STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications

While the supply of STEM teachers is important, the characteristics and quality of STEM teachers represent another important facet. To start, research has shown that female students who have female teachers can have increased self-efficacy and achievement (Sansone 2017) and that high schools with more female math and science teachers are more likely to have female students enroll and graduate with STEM degrees (Bottia et al. 2015). In terms of the teacher’s race/ethnicity, racially minoritized students have better academic outcomes when they have teachers who match their race/ethnicity (Redding 2019). For instance, when Black students are randomly assigned to at least one Black teacher in elementary school, they are substantially more likely to graduate from high school and enroll in college (Gershenson et al. 2022). For STEM students specifically, having a STEM mentor of one’s own gender or race in college was important for many students, particularly women and students of color (Blake‐Beard et al. 2011). In short, STEM teacher demographics have important implications for students’ aspirations and academic outcomes.

In terms of teacher quality, prior works have indicated that teachers who have more math and science content knowledge have more positive effects on student learning (Clotfelter et al. 2010; Goldhaber et al. 2017; Hill 2007; Hill et al. 2005). These studies establish that better-prepared STEM teachers produce higher-achieving STEM students, which is linked to higher STEM aspirations, particularly for women (Mann and DiPrete, 2016; Sax et al. 2015). Contemporary STEM instruction often incorporates more project-based learning approaches, requiring more teachers ability to communicate twenty-first-century competencies to their students (Morrison et al. 2021). Improving STEM teachers’ knowledge of content and curriculum would also improve STEM student outcomes (Hill et al. 2020). Despite the push for more highly qualified STEM teachers from federal to state initiatives (e.g., Educate to Innovate, 2024; Race to the Top, n.d.), STEM teachers remain the least prepared as 30% of math teachers, 26% of biology teachers, and 54% of physical science teachers do not have a major or degree relevant to their teaching assignment relative to 21% of English teachers (Hill and Stearns 2015).

An additional concern related to STEM teacher quality is that underserved and underrepresented students often experience less access to high-quality teachers than their more advantaged peers. For instance, low-income and minority students are two to three times more likely to be taught by out-of-field teachers, teachers with neither certification nor major related to the subject matter (Almy and Theokas 2010; Peske and Haycock 2006). Out-of-field teachers often present less complex classroom activities, have worse classroom climate, and less student engagement compared to in-field teachers (Du Plessis 2018). Moreover, out-of-field STEM teachers have alternative certificates and are more likely to serve Title I schools than their counterparts with standard certification (Carver-Thomas and Darling-Hammond 2017).

Data and methods

I use two sources of national data to examine the trends in STEM teacher supply, characteristics, and qualifications: (1) Title II data from the Higher Education Act and (2) the Schools and Staffing Survey (SASS) and its new iteration, the National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS). These two data sources are the most comprehensive and up-to-date data on STEM teachers.Footnote 1

Title II of the Higher Education Act is a federal law that governs the data collection and reporting on teacher preparation and education programs (Fountain 2023). Institutions of higher education and state departments collect data on teacher education programs, including enrollment and completion, and report it to Title II, and these data also include the number of teachers prepared by academic major and subject. These data are then subjected to reporting requirements and verification between the federal government and state agencies. Broadly speaking, Title II data from 2010 to 2022 provide the most comprehensive information on the supply of STEM teachers at the state and national levels. Title II provides yearly completion, defined as having met the preparation program standards, for traditional and alternative teacher preparation programs. I identify STEM teachers in Title II if STEM was their prepared subject area (CIP codes 13.13XX).

To supplement the Title II data, I also merge economic variables measured at the state level to examine how state-level conditions relevant to the labor market theory of supply and demand may be associated with the production of STEM teachers. These measures come from a variety of sources, including the BLS, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the School Finance Indicators Database (SFID), the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), and the Common Core of Data (CCD). Economic factors include the unemployment rate, measures of state gross domestic product (GDP), cost-of living adjustment for the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment, a measure of poverty, state and local revenue progressivity measure, and state property tax revenue as well as state-level per-pupil-expenditure and average teacher salary.

The SASS and NTPS, administered by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), consist of nationally representative samples of public school teachers in the United States and include about 30,000 public school teachers every wave. SASS/NTPS uses a stratified probability sample design where schools are selected using a probability proportional to the size of the school within grade-level strata within state strata. A sample of teachers is selected within each sampled school based on selected characteristics for state and national representation. The SASS and NTPS include detailed comprehensive data on teacher characteristics and qualifications, such as race/ethnicity, gender, teacher education, and experience, which is ideal for exploring how STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications have changed over time. These data have been used and verified in hundreds of studies (for more documentation, see Cox et al. 2017).

To provide a thorough contemporary examination of the STEM teacher workforce nationally over time, I use SASS and NTPS data from 2004 to 2021. Specifically, I use the 2003–2004, 2007–2008, 2011–2012, 2015–2016, 2017–2018, and 2020–2021 waves. Data on STEM teacher demographic characteristics and education variables are available for every wave. Missing data are less than 1% over the entire time frame. I note that some variables of interest are not available in the 2017–2018 wave as the NTPS rotates the survey module every other wave. STEM teachers are defined as teachers who report their main teaching assignment as either natural science, such as physics and chemistry, computer science, or mathematics. Other areas of technology and engineering that are not well defined across the different waves and sometimes not accepted as STEM are not included. For instance, I do not include vocational or career training in the definition of STEM teachers as CTE is sometimes counted separately from STEM.

In the analysis of the SASS and NTPS data, through the lens of the education production function, I examine teacher characteristics, such as gender, race/ethnicity, age, and novice teacher status, as well as their qualification, such as having graduate degree(s), having certification, and being a qualified STEM teacher (i.e., if their first or second major is in a STEM field or they have state certification in a STEM subject). In terms of school characteristics, I consider the results separately for higher- and lower-poverty schools as the resources and working environment for STEM teachers differ substantially in these environments. In sum, I am able to analyze key STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications that are relevant for the STEM teacher workforce and their implications for students.

Analysis

This study included both descriptive and regression analyses, and each data source was analyzed separately. Using the Title II data, in descriptive analyses, I examine the potential supply of new STEM teachers nationally over time. Using the SASS and NTPS data, I examine changes in STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications nationally over time. In regression analyses, I use ordinary-least square (OLS) regression models to estimate the association between average STEM teacher preparation across institutions over time and economic and institutional characteristics (see Wooldridge 2010). This model can be written as:

Y is the supply of new STEM teachers for institution i from state s in year t. ({{boldsymbol{Size}}}_{{boldsymbol{i}}}) represents a series of dummy variables for the size of the institution (small, medium, and large; in reference to small institutions with fewer than 5000 students); ({{boldsymbol{Sector}}}_{i}) is a series of dummy variables representing four institutional categories: private non-profit four-year-and-higher, private for-profit four-year-and-higher, public non-profit two-year, and private for-profit two-year (in reference to public non-profit four-year institutions). HBCU is a binary variable indicating whether the institution is recognized as a Historically Black College and University by the federal Department of Education. ({{boldsymbol{Econ}}}_{s}) is a series of economic variables (i.e., state GDP, property tax revenue, per-pupil expenditure, and average teacher salary). ({gamma }_{t}) is a year-fixed effect to account for temporal shocks that may be specific to particular years. Lastly, ({e}_{{ist}}) is a random error term. I employ heteroskedastic-robust standard errors in all models. Since economic variables are not available for all years, I exclude them from some models that examine institutional characteristics.

While I view these results as associational, the methods employed here enable me to reduce potential biases that come from omitted variables that are correlated with both the independent and dependent variables (Wooldridge 2010). Examples of these omitted variables include potential STEM teacher candidates’ perception of the teaching profession or available grants and financial aid to lower the cost of attending teacher preparation programs, factors that are important but may not be available to be included in the analysis. In short, the regression models allow me to examine the relationship between each independent variable of interest and the supply of new STEM teachers while accounting for a series of other important factors that are correlated with both the independent variable and the outcome.

Results

STEM teacher production

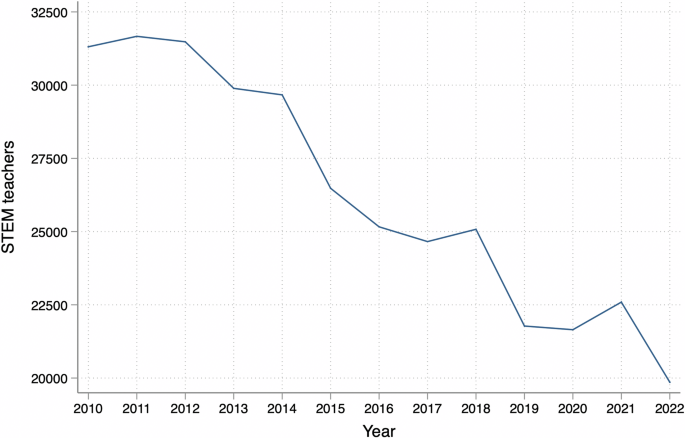

Data from Title II indicate that nationally STEM teacher production has decreased substantially from a high of nearly 32,000 STEM teachers in 2011 to under 20,000 in 2022, which represents a 37% drop over the last decade (Fig. 1). The average number of STEM teachers produced at IHEs each year has decreased from about 22 to about 14 teachers (Appendix Fig. 4) where the reduction is more pronounced at smaller institutions, dropping from 16.1 to 6.5 STEM teachers, relative to a drop from 29.7 to 23.5 at larger institutions (Table 1). The decline of STEM teacher production can also be observed in virtually every state (Appendix Fig. 4). Overall, the data strongly suggest that STEM teacher production has dropped precipitously throughout the U.S.

The production of STEM teachers nationally over time.

Next, to examine this further, I explore the extent to which economic and institutional characteristics are associated with STEM teacher production (Table 2). In Model 1, I examine the relationships between institutional characteristics and STEM teacher production. I find that, while production has decreased for institutions of all sizes, large institutions produce about 18 more STEM teachers on average compared to smaller institutions (with less than 5000 students). Relatedly, STEM teachers mostly come from public four-year institutions relative to two-year and four-year private non-profit and for-profit institutions. For instance, holding all else constant and accounting for secular trends, private non-profit four-year institutions produce about 10 STEM teachers less than public four-year institutions (Model 1 of Table 2). Lastly, HBCU institutions also produce less STEM teachers than their counterparts.

In Model 2, I add economic indicators to examine their relationships with STEM teacher production. I find that many economic indicators are highly associated with teacher production. For instance, accounting for secular trends over time and institutional characteristics, I find that states that have higher GDP and states with more progressive taxes are associated with more STEM teacher production. In particular, states with higher state and local revenue progressivity are associated with nearly 3 more STEM teachers produced at IHEs relative to other IHEs with lower revenue progressivity. I also find that states with higher unemployment rates are associated with higher STEM teacher production, suggesting that people with STEM skills are more likely to become STEM teachers when they are less able to find industry jobs. Relatedly, I find that average teacher salary is strongly associated with STEM teacher production. In particular, for every $10,000 increase in average teacher salary, there is a corresponding increase of 6 STEM teachers. In terms of cost of living, STEM teacher production is negatively associated with higher cost of living, but the magnitude is fairly small (one standard deviation increase in a cost-of-living adjustment for a two-bedroom apartment is associated with a decline of 0.03 STEM teachers). Similarly, while per-pupil-expenditure per $10,000 is also negatively associated with STEM teacher production, the magnitude is rather small (−0.0005; p < 0.01). In short, there is substantial evidence that the production of STEM teachers is strongly tied to economic conditions as the labor market theory of supply and demand would suggest.

STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications

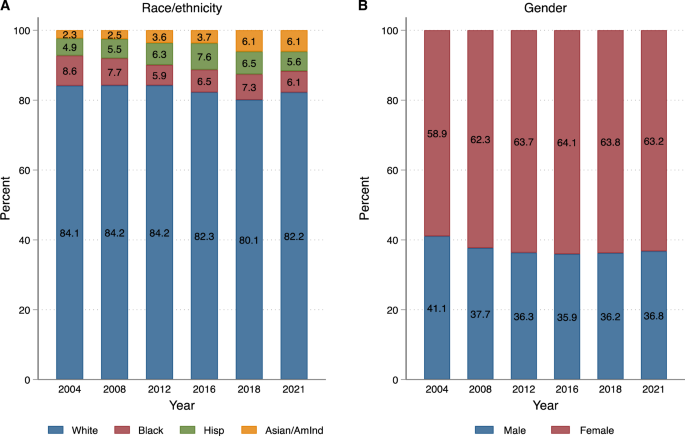

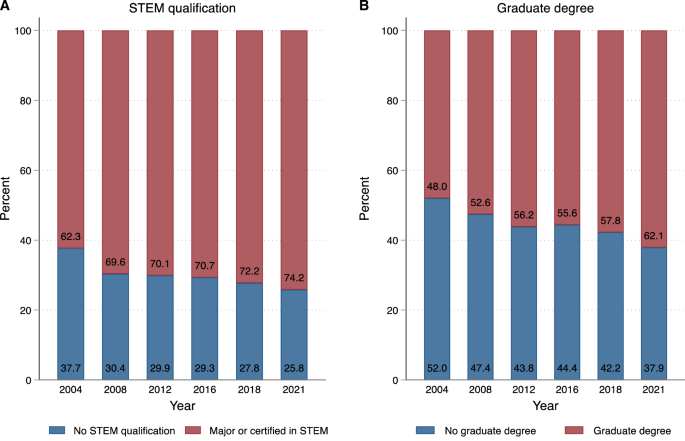

In this section, I analyze changes in STEM teacher characteristics from 2004 to 2021. I focus on the most interesting findings below, but all descriptive results can be found in Appendix Table 4. To start, a little more than four out of five STEM teachers in the 21st century were White while about six percent are Black, Hispanic, and Asian/American Indian each (Fig. 2). In particular, the percentage of Asian and American Indian STEM teachers has grown from 2.3 percent in 2004 to 6.1 percent by 2021. Moreover, there was also an increase of female STEM teachers in the profession, growing from about 59 percent to 63 percent. During this time period, I also observed that STEM teachers were becoming more qualified by at least two measures. First, from 2004 to 2021, the percent of STEM teachers who have graduate degrees has increased from 48 percent to 62 percent (Fig. 3). Second, the percentage of STEM teachers who have their first or second major degree of study in STEM has increased from 62 percent to 74 percent (Fig. 3). Lastly, I note that the inflation-adjusted STEM teacher salary has stagnated in the 21st century (actually a decline from $62,400 in constant 2021 dollars in 2004 to $61,200 in 2021).

A Illustrates changes in STEM teacher race/ethnicity over time, and B illustrates changes in STEM teacher gender over time.

A Illustrates changes in STEM teacher qualification over time, and B illustrates changes in STEM teacher graduate degree over time.

While we observe these important changes over time, we are also concerned about how they vary for traditionally disadvantaged schools, schools serving a higher concentration of racially minoritized students, and students receiving free-and-reduced lunch. In Table 3, I show the differences in STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications between lower-poverty schools and higher-poverty schools in 2012 and 2021 (results for majority White and racially minoritized schools are shown in Appendix Table 5). In 2012, Black STEM teachers were 7.7 percentage points more likely to work in higher-poverty schools than in lower-poverty schools, and on the other hand, White STEM teachers were 16.3 percentage points less likely to work in higher-poverty schools. Novice STEM teachers were more likely to work in higher-poverty schools while those with a graduate degree or STEM qualifications were much less likely to work in higher-poverty schools (3.9 percentage points and 8.0 percentage points respectively). Moreover, STEM teachers in higher-poverty schools earned about $6100 less than their counterparts in lower-poverty schools. In other words, in 2012, there were systematic differences between STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications in higher and lower-poverty schools. By 2021, some of these differences have narrowed, but gaps remain.

In 2021, Black STEM teachers were 7.3 percentage points more likely to work in higher-poverty schools than in lower-poverty schools, and on the other hand, White STEM teachers were 14.5 percentage points less likely to work in higher-poverty schools. STEM teachers with a graduate degree or STEM qualifications continued to be less likely to work in higher-poverty schools (7.4 percentage points and 7.3 percentage points respectively). STEM teachers in higher poverty earned nearly $4000 less than those working in lower-poverty schools. In short, the differences in STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications between higher and lower-poverty schools have persisted, albeit decreasing over time, from 2004 to 2021. The main exception here is that the STEM teacher salary gap has narrowed between higher and lower-poverty schools.

In Appendix Table 5, we observe that many of these differences also exist between majority White and racially minoritized schools. For instance, minority STEM teachers were more likely to work in racially minoritized schools than majority White schools. STEM teachers with a graduate degree were less likely to work in racially minoritized schools than majority White schools, though there were no differences in STEM qualification. Moreover, there were no salary differences for STEM teachers working in majority White and racially minoritized schools.

Discussion and conclusion

Prior works have suggested that the STEM workforce goes hand-in-hand with the STEM teacher workforce (Diekman and Benson-Greenwald 2018). Our evidence suggests that the supply of STEM teachers is at a critical juncture with strong implications for the future STEM workforce. Overall, the results indicate that STEM teacher production is responsive to economic conditions as the labor market theory of supply and demand suggests, and from the perspective of the education production function, there are changes to STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications that have implications for student outcomes.

Nationally, we are seeing a huge drop in the production of STEM teachers over the last decade, and institutions of higher education are producing fewer STEM teachers every year. This is particularly problematic as previous works suggested that we needed an additional 10,000 STEM teachers every year for a decade, not a loss of more than 10,000 over ten years (Feder 2022). Stated differently, not only we have been unable to increase the production of STEM teachers, but rather, there are less STEM teachers coming into the profession now than there were a decade ago. This trend threatens the US ability to produce STEM graduates to compete with other countries. This work is the first to clearly document the extent of the decline in STEM teacher production nationally and over time so that future work can explore why STEM teacher production has decreased and how to increase the supply of STEM teachers.

In accordance with the economic labor market theory of supply and demand, this current and prior works suggest that there are economic conditions associated with STEM teacher production. STEM teachers are more likely to come from states with higher economic outputs or more progressive taxes. When the unemployment rate is higher or when teacher salary is higher, STEM graduates are more likely to become STEM teachers. In particular, even after accounting for numerous factors and economic conditions, the results suggest that for every $10,000 increase in average teacher salary, there is a corresponding increase of 6 STEM teachers in annual production at an IHE. This finding along with prior works showing how postsecondary grants can increase STEM education participation and how increases in salary and compensation can improve teacher recruitment and retention, particularly for STEM teachers (Nguyen et al. 2020; Pham et al. 2021), suggest strategic and targeted financial investment into STEM education, both at the K-12 and higher education, can improve both STEM teacher pipeline and future STEM workforce.

In particular, policymakers should award more grants and scholarships, including larger awards, to potential STEM teacher candidates as STEM teacher candidates are responsive to economic conditions. Many states have started to award teacher candidates more and larger awards, particularly when they have good academic standing and are in high-needs areas like STEM (e.g., Arkansas S.B. 26). The NSF Robert Noyce scholarship can also induce people to become STEM teachers (e.g., Morrell and Salomone 2017). Likewise, loan forgiveness for STEM teachers would likely increase the number of potential candidates who may forgo higher earnings in industry to work as STEM teachers. Existing evidence suggests that these financial incentives can shape potential candidates’ decision to teach in STEM (Smith 2021). Moreover, targeted programs that incentivize STEM teachers to teach in high-needs schools have also been found to be effective (Podolsky and Kini 2016). Higher salaries specifically for STEM teachers can also be used to recruit more STEM teachers (See et al. 2020). Simply put, the results of this current work and prior research indicate that policymakers can leverage existing tools to increase STEM teacher production.

In terms of teacher characteristics and qualifications, there is some potential good news as the diversity and quality of the STEM teacher workforce is slowly increasing over time. In the last twenty years, we have seen a small increase in the number of racially minoritized STEM teachers, largely from Asian backgrounds. The hope here is that the diversification of STEM teachers will lead to the diversification of STEM graduates to meet current demands and the need to broaden STEM participation (Benish 2018; Camilli and Hira 2019). Recent research suggests that there are multiple ways to recruit teachers from different racial/ethnic backgrounds (e.g., Anderson and Anderson 2022; Liu et al. 2017). Moreover, bridging the gap between the labor market theory of supply and demand and the education production function, targeted scholarships and salary incentives for racially minoritized STEM teachers would increase both the supply of STEM teachers and also diversify the profession.

While we have observed a growth in the proportion of female STEM teachers, we still observe substantial a gender gap in STEM graduates, even though female STEM students are not more likely to drop out in the first year of STEM programs than male students in the U.S. and internationally (Griffith 2010; Vooren et al. 2022). Prior works have shown that STEM degrees continue to be male-dominated and that institutes of higher education need to do more to support female STEM graduates (and potential teachers) to enroll and graduate (Vooren et al. 2022; Xu 2017). To this point, having more female STEM professors to mentor the next generation of students, particularly female STEM students, may provide the support and guidance that students need to feel supported and graduate (Blake‐Beard et al. 2011). Organizations like the Women in Science and Engineering (WISE) can increase support for women in STEM (Gold et al. 2021).

On other fronts, the number of STEM teachers who have graduate degrees or have a major degree of study in STEM has increased by 14 and 12 percentage points respectively, and previous works have consistently documented the positive effects of teachers’ math and science knowledge on student learning (e.g., Clotfelter et al. 2010; Hill 2007). Moreover, these positive changes have happened in both traditionally disadvantaged and more affluent schools. While there are systematic differences in the STEM teacher characteristics and qualifications in higher and lower-poverty schools, some of these differences have narrowed over time. In other words, STEM opportunities are improving in some ways for all students and improving faster for traditionally disadvantaged students.

In conclusion, this work demonstrates that, while STEM teacher production has decreased substantially over the last ten years, STEM teacher production is sensitive to economic conditions. Strategic and targeted financial investment into STEM education can increase more STEM graduates and more STEM teachers. Similarly, policymakers have existing tools they can use to support more female STEM graduates and racially minoritized STEM graduates, including STEM teachers, and to diversify the teaching profession.

Future directions

While this work makes several contributions in examining STEM teacher supply and qualifications, it does have some limitations and related opportunities for future work to explore. First, in some ways, the positive changes in teacher qualification are surprising since we observe a reduction in the STEM teacher supply. One potential explanation is that schools may be increasing the classroom size for STEM courses or offering fewer STEM courses when they are unable to hire STEM teachers, while STEM teachers may earn graduate degrees to increase their salary since teachers with graduate degrees earn more on the pay schedule than teachers without graduate degrees. Moreover, while economic conditions, such as teacher salary and unemployment rates, are related to teacher supply, they may also influence teacher quality through supply dynamics. For instance, we should examine if positions with low teacher salaries do not attract certified STEM teachers and therefore are taken up by alternatively certified teachers or lower-qualified teachers. Alternatively, we could explore if certified or high-quality STEM teachers move to districts with better economic conditions. While these questions are beyond the scope of this paper, future work using longitudinal administrative data should attend to these important issues.

Responses