The transformation of agriculture towards a silicon improved sustainable and resilient crop production

Introduction

Sustainable and resilient food production is a key component if future food security is to be achieved for the world’s projected 10 billion people by 20641,2,3. Barring changes in consumption towards more plant-based diets, strategies to ensure sufficient food production largely involve increasing yields (production per unit area) as expanding agriculture to currently uncultivated land is unacceptable due to the resultant negative effects on biodiversity1. In already intensively used agricultural systems, yield increases are strongly linked to the application of phosphorus (P) or nitrogen (N) fertilizers, which goes hand in hand with high energy consumption during fertilizer production4. Increased fertilizer production is not sustainable and already exceeding the planetary boundaries, particularly as the global stock of mineral deposits containing apatite (the main P-containing mineral used for P fertilizer production) is not expected to last more than ~260 years5,6. Further, a large share of the P fertilizer applied to agricultural soils is not available to plants, as phosphate strongly binds, for example, to iron (Fe)-bearing pedogenic oxides/hydroxides7, further reducing the sustainable use of P fertilizer.

At the same time, as yield levels increase with higher fertilization levels, crop production is more variable in response to drought and high temperatures8,9, which are projected to intensify under climate change10,11. Increased drought risks threatens food security through decreasing yield12,13,14,15 and higher crop price volatility16. During intense drought, soil water content decreases to values near the permanent wilting point where water is no longer available for crops resulting in severe drought stress and wilting17. During such conditions, photosynthesis is inhibited by decreased stomatal conductance18. Crops possess different strategies to cope with water scarcity by (1) increasing stomatal closure to limit transpiration driven water loss, (2) increasing of water uptake due to morphological changes in root architecture, or (3) osmotic adjustments within the plants19,20.

Of particular interest in the context of limited P supply and increasing drought stress is the idea of applying reactive silicon (Si) to support restoring natural Si cycles and their associated functions in managed agroecosystems21,22. Natural cycling of Si includes the accumulation of Si in plant biomass and its subsequent release during litter decomposition (Box 1). While natural Si cycling increases reactive Si in soils, it is interrupted in current conventional intensified agricultural systems as the export of Si in crop harvest exceeds Si inputs23,24. With a Si content of approximately 28% (w/w) in the Earth’s crust Si is virtually everywhere, but most of this Si is very slowly released by silicate mineral weathering24. The more reactive forms of Si are (i) dissolved silicon (DSi) comprising monomeric silicic acid (plant available Si) and polymeric silicic acid and (ii) the so called amorphous silica (ASi) fraction, which is defined as X-ray amorphous or extractable by several alkaline extractants24.

An increasing number of studies reported that crop Si accumulation improved crop performance under stress25,26,27,28,29. A literature review showed a clear crop yield increase for many important crops after Si fertilization21. More recently, several studies at field scale presented positive effects of Si fertilization on biomass production and yield for crops30,31,32 in addition to the large number of studies reporting increases in rice yield during the last decades33. An additional effect of Si, demonstrated mostly for rice so far, with huge importance for reducing pesticide use in crops34, is the suppression of pathogen fungi affecting crop biomass through Si deposits in, e.g., plant leaves33,35.

To cope with the challenges of increasing global food consumption resulting from rising population coupled with economic growth, decreasing natural resources, biodiversity loss, and the impacts of climate change, a sustainability transformation of agricultural and food (agri-food) systems is increasingly understood as inevitable36,37,38. With agricultural transformation necessarily covering many aspects, from more sustainable diets and farming practices to a reconceiving of food as a human right and part of the global commons, any transition towards sustainable and resilient agri-food systems will be shaped by local context and values36,38,39. From this viewpoint, we outline the potential role and management options for re-establishing Si cycling in cropping systems through integrating reactive Si in crop production. We are well aware that the success of any new management strategy depends on a range of accompanying market, infrastructure, regulatory and cultural factors36,38, and changes in management strategy alone will likely serve only as incremental change and not support alone a wider transformation towards sustainability40.

The aim of this Perspective is to raise awareness on the potential to manage reactive Si in agriculture, horticulture, vineyard, and fruit cultivation, supporting further research on pathways towards its wider integration and anticipating challenges. Hence, we focused on important biotic and abiotic stressors for agriculture, for which Si effects were already known. In this context, we summarize the positive effects of Si on P availability in agricultural soils and describe the role of Si for the mitigation of drought and pathogen impacts on crops. Finally, we outline the transformation of conventional agriculture to a Si-based sustainable crop production and address implications for future research.

Increased phosphorus availability by Si

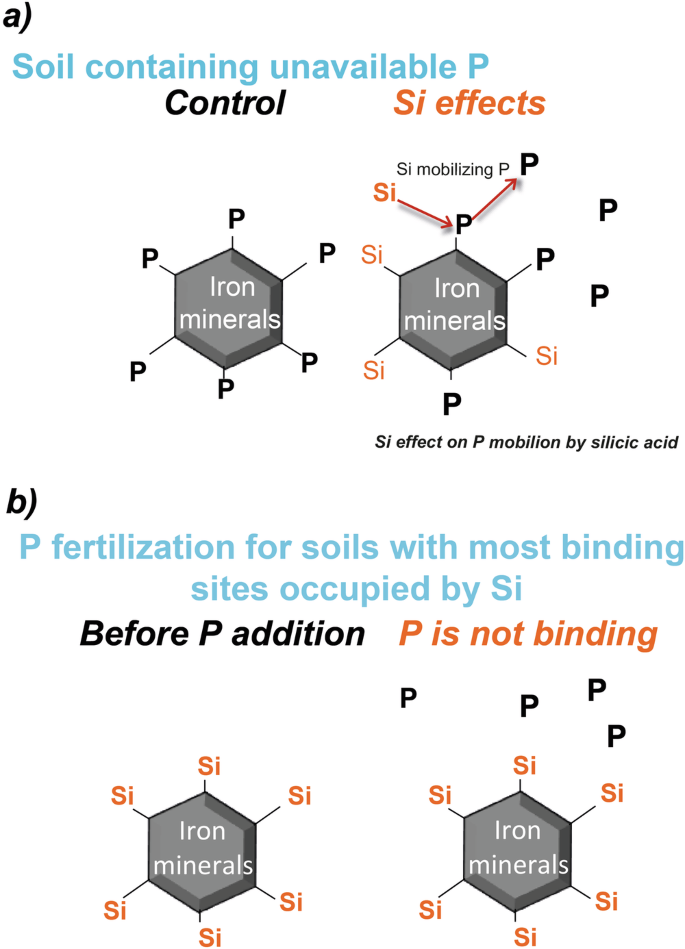

Phosphorus is a main limiting nutrient for crop production41,42 and a limited resource as minable deposits are declining rapidly5. At the same time, less tailored P fertilization leads to large P losses from agricultural soils to aquatic system leading to eutrophication42,43. Consequently, more efficient use of P fertilizer in crop production is required, potentially decreasing the need for P fertilizer and reducing the share of P fertilizer bound in the pool of plant unavailable P. The role of soil Si-fertilization to improving crop P nutrition44,45 has been known for approximately 100 years, confirmed by several more recent studies31,33,46,47. Abundant evidence indicates several underlying mechanisms for the improved P nutrition of crops due to Si31,48,49: (1) competition of dissolved Si (either monomeric or polymeric silicic acid) with nutrients, e.g. P for binding at the surface of soil particles49,50,51; and (2) application of ASi reducing the hydraulic conductivity of the soils at saturation52. Reduced hydraulic conductivity leads to a reduction of Fe3+ phases to Fe2+ with slower transport of electron acceptors (other than iron) to certain micro sites. In turn, this leads to a reductive dissolution of P-containing Fe oxides, consequently releasing P into the soil solution, increasing P availability for crops. Mobilization of P from the hitherto pool of plant unavailable P by Si may last from a few years to several decades depending on the soil stock of plant unavailable P. Even after all P is exhausted from the soil, it is hypothesized that farmers would need less P-fertilizer if the soils exhibit high Si availability with Si occupying most binding sites at the surface of soil particles (Fig. 1), increasing the availability of applied P. However, experimental evidence here is still lacking, though it is a promising future research field to potentially result in substantial reductions in the need for P fertilizer.

Effects of Si on P showing (a) how silicic acid is competing with P for soil sorption sites mobilizing plant unavailable P and (b) how a P fertilization could look like with most binding sites occupied by Si.

Si reduces drought impacts

The capacity of soils to store and supply water to crops is crucial for yield production for many crops and regions53 especially as drought intensifies under climate change54. For Europe, yield losses of up to 25% are projected under climate change55 with drought being the dominant factor for this decline56. In response to drought, crops have developed several adaptive traits to avoid the loss of water such as fast stomatal closure, reduction of stomata size and number, decrease of leaf size and number, change in partitioning of assimilates to plant organs, morphological changes in root architecture to increase water uptake from soil, and hormonal regulation for an optimized water usage19,20. During severe and or prolonged drought, soil available water decreases, prohibiting water uptake by roots, leading to increased plant stress in terms of inhibition of growth and reduced carbon accumulation up to enhanced senescence17.

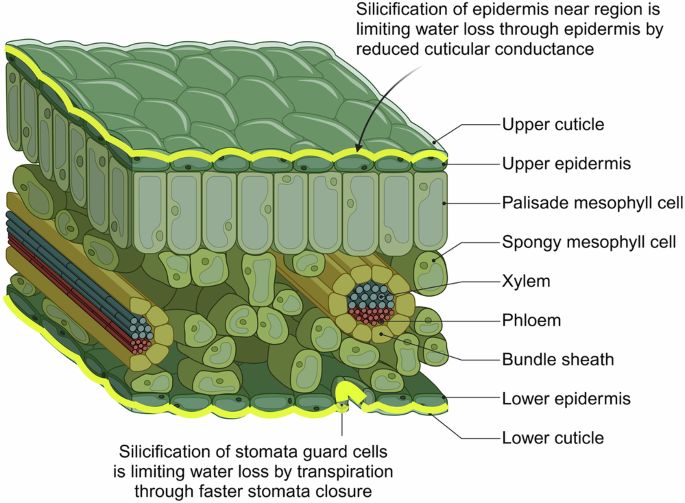

Several studies have demonstrated reduced water stress during drought due to plant Si accumulation. This is attributed to changes in physiology as a response to increased Si availability (DSi) in soils with positive effects on crop biomass and yield levels25,26,27,28,57,58. These effects can result from larger leaves25,29, increased root length26,27,28, or improved photosynthesis and stomatal conductance26,27,28. It was shown that Si deposits in the region of the epidermis reduce water loss by reduction in stomatal and cuticular conductance59 (Fig. 2). Recently, it has been shown that Si application to the soils improved rhizosheath formation, root hair length, and density, as well as decreased transpiration rate of crops60. Although the studies showing a clear effect of crop Si accumulation on drought stress mitigation by changing plant physiology, a study on rice drought stress response comparing a knockout mutant of rice for Si uptake transporter (disabling plant Si accumulation) and a wild-type rice (with high Si accumulation) concluded that plant internal Si effects may be low61 compared to the effect of ASi increasing water availability in the soils52.

The scheme shows Si deposition (yellow color) in cereal leaves and its positive effect on water loss via transpiration due to faster stomata closure and reduced cuticular conductance. This figure was created using BioRender.com.

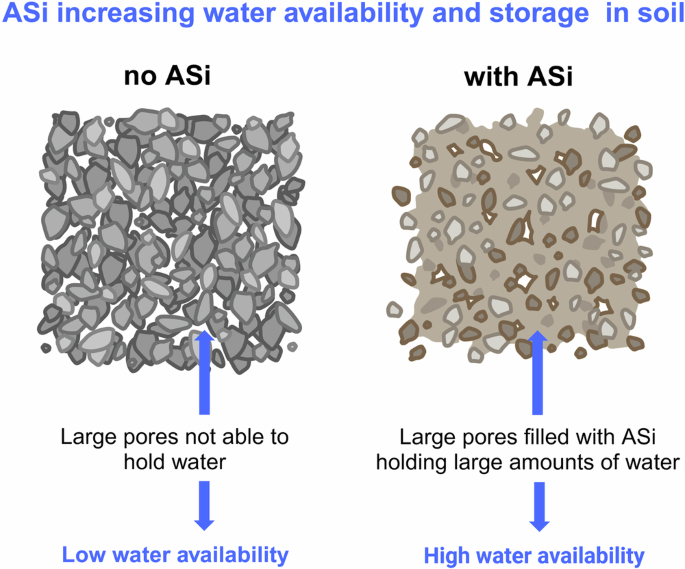

Indeed, recent studies demonstrated that soil ASi content is a main control on water holding capacity and plant available water in soils52,62,63. For example, increasing the soil ASi concentration by 1% (weight) improved the plant available water in these soils by more than 40%52. This effect of ASi increasing both the water availability and storage in soils can be explained by ASi leading to more water retention in larger soil pores, especially in coarse texture soils (Fig. 3). ASi was found to improve soil water retention in soil pores by increasing the capillary force64, as the smaller the pore size, the greater the capillary force. ASi improves water supply for crops under drought, sustaining the transpirational water demand of crops63 by increasing the hydraulic conductivity especially for coarse-textured soils, maintaining water access to crops even as soil dries52,63.

The ASi is filling the pores of the coarse texture soil. This figure was created using BioRender.com.

The positive effects of ASi increasing soil water availability and storage maintaining crop production and yield under drought have been confirmed in field experiments31,32,33. In coarse-textured soils ASi may shift the pore size distribution towards smaller pore sizes, strongly suggesting changed pore size distribution being the reason for the increased water retention of those soils in addition to the high water holding capacity (700–800%) of the ASi itself52. In those pores, the ASi is holding large amounts of water due to the high water holding capacity of ASi and decreasing the pore volume52. However, the effect of ASi in improving soil water availability and retention was not detected for fine-texture soils, as ASi may rather clog smaller pores65. Furthermore, fine-textured soils have a higher content of particles in the silt and/or clay size fraction, which lead to soils with small pores only. Such small pores can hold water more efficiently as compared to coarse texture soils.

Overall, reactive Si holds a large potential to mitigate drought stress during crop production via soil and plant internal effects supporting more resilient crop production under increased drought stress intensities and duration expected with climate change. Studies showing effects of reactive Si (DSi and ASi) on crop yield and performance during drought are still limited in terms of different soil types, climatic conditions, crop, and cultivar types. Unclear is also how effects would scale up if Si is applied to larger regions. This calls for increased field level measurements of reactive Si in agricultural, horticulture and vineyard research programs to get a better overview of the existing levels of reactive Si in different soils in relation to management practices, crop types, and climatic conditions.

Pathogen control in crop production by Si

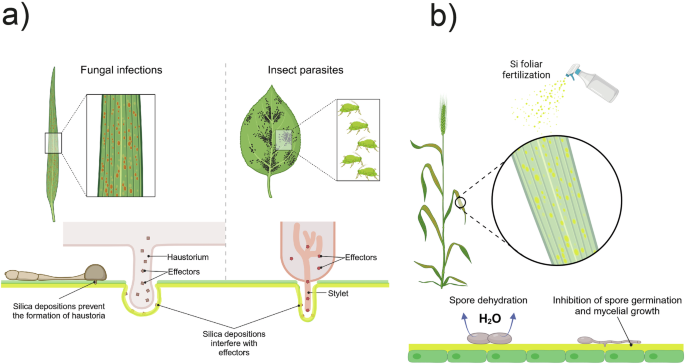

Si has pronounced beneficial effects on plants under biotic stress, which has been well-documented by a large number of studies33,66. Silica depositions in plants can act as a mechanical barrier increasing plants’ resistance against the penetration of (insect) herbivores and pathogens. The various Si-related benefits for plants under abiotic and biotic stress reported in the literature have been unified in the so-called “apoplastic obstruction hypothesis”67. According to this hypothesis silica deposition in the apoplast enhances the resistance of plants under biotic stress on two different ways: (i) by preventing the formation of haustoria, i.e., specialized hyphae formed by fungal parasites to invade plant cells and (ii) by interfering with the injection of effectors (specialized small proteins) secreted by parasites (e.g., fungi or insects) to suppress plant defense responses (Fig. 4a). Regarding abiotic stress these silica deposits are hypothesized to (i) fortify apoplastic barriers of the plant vasculature precluding the transport and accumulation of toxicants like metal(loids) (“heavy metals”) into the shoot and (ii) co-precipitate with toxicants in the extracellular matrix. In plants with Si deficiency such toxicants can cause an elevation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in cells, which can be accompanied by increased oxidative stress, decreased enzyme activity, or changes in gene expression. Indeed, these positive Si effects on plant physiology have been described in numerous studies68,69.

Illustration of the positive effects of (a) silica deposition on plants’ resistance against attacks by fungi and insects and (b) Si foliar fertilization on fungal infections. This figure was created using BioRender.com.

Examining Si deposition in wheat leaves, Leusch70 showed that in the locations where mildew tried to penetrate the wheat leaves Si deposits disabled the fungal penetration. More recently, Knight and Sutherland71 observed that almost all cell types in wheat leaf sheath tissues were extensively colonized by Fusarium, except for the vascular bundles and silica cells. Such effect of Si deposits in aboveground biomass reducing fungal penetration is widely accepted for rice plants33,35. Moreover, the effect of the plant Si content reducing herbivory is known for several plant and herbivore species72,73. Si accumulation in grasses was found to increase due to exposure to invertebrate and vertebrate herbivores73,74. However, it is not clarified yet, if silica deposition is controlled and specific, thus actively regulated in plants35,75, or passively driven by plant transpiration76,77.

Si foliar fertilization has been found to be a promising approach for fungal disease control in crop production69. Foliar Si applications are assumed to decrease fungal infections by spore dehydration (osmotic effect)78 and antifungal activities (inhibition of spore germination and mycelial growth) by silicates79,80 (Fig. 4b). Taken into account that Si foliar application can be effective at much lower rates compared to soil application81, Si foliar application might be a promising method for fungal disease control in sustainable crop production. However, the benefits of foliar vs soil Si application vary between species. Foliar Si application is very effective at preventing pathogen infection in fruit crops69,82, but soil application may have more overall benefits for gramineous crops that can effectively accumulate large amounts of Si in their aboveground biomass.

Si in soils has also shown a range of positive effects on regulation of biotic stressors on plant health. Soil microorganisms are key in nutrient cycling, and thus are crucial for maintaining soil health and sustainable crop production83. In this context, the relationships between microorganisms, especially bacteria and fungi, and soil Si content have been the focus of research. It was shown that ASi application to soil might favor an increase in beneficial microbes in soils and a decrease of pathogens84. However, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood yet. Silicate fertilization generally seems to stimulate microbial functions that are beneficial for crop production. Slag silicate fertilization, for example, was found to increase the relative abundance of saprotrophic fungi enhancing the decomposition of organic matter in flooded rice fields85. In another study, the abundance of soil microbes involved in, e.g., nutrient cycling and fixation increased after Si fertilization86. Further, analyses of microbial communities in the rhizosphere and surrounding soils showed positive effects of Si fertilization on plant-growth-promoting microbes in sugarcane and wheat fields84,87,88. Overall, Si has beneficial effects for sustainable and resilient crop production by decreasing the pressure from pathogens and herbivores as well as by improving the microbial community with increasing beneficial microbes and decreasing pathogens in the soil.

Towards a Si-improved sustainable and resilient crop production

To benefit from the positive effects of Si in agroecosystems, Si-fertilization is required. Current high-yield agriculture with its high annual exports of reactive Si resulted in the ASi depletion of agricultural soils with consequences for Si availability (anthropogenic desilication)24. For example, each year, rice producers apply ~900 kg Si ha−1 or more (up to 3000 kg Si ha−1)89 of Si fertilizer, as Si is highly important for rice cultivation90. The most widely applied Si fertilizers are wollastonite, silica gel, liquid suspensions or solutions of meta-silicate, silicic acid, potassium-silicate, slags, fly ash, as well as rice and Miscanthus straw, biochar, and manure91,92,93. We recommend the application of synthetic ASi, straw, and silica gel, as the physical and chemical properties of the Si in those compounds is largely the same as for natural ASi in soils52,94,95.

Common synthetic ASi production from quartz sand requires large amounts of energy96, which is not sustainable. As such, efforts to replace the ASi produced from quartz sand by ASi from biomass (e.g., recycled crop straw) is a more sustainable alternative (Fig. 5). Production of ASi from rice biomass was shown to achieve a quality comparable with synthetic ASi products97. Such ASi production from biomass requires less energy compared to synthetic ASi production from quartz sand96 but requires a systems-based approach to production38 if it is to be sustainable. To avoid tradeoffs between food and ASi production, biomass for ASi production could come from non-food plants with large biomass and a very high content of ASi98.

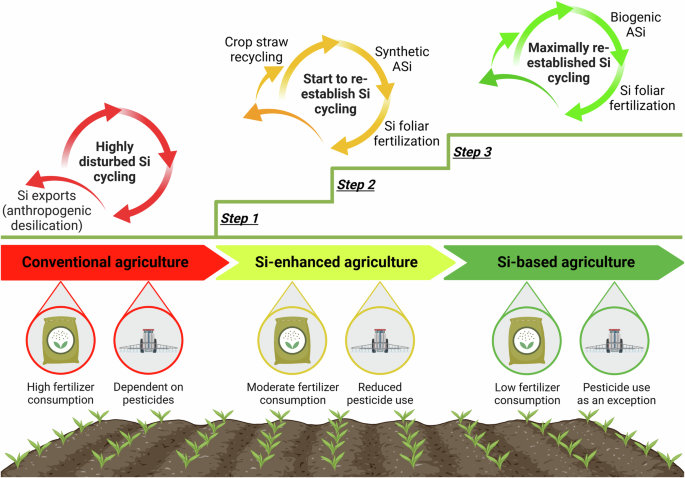

Step 1: start of crop straw recycling, soil application of synthetic ASi (produced with conventional energy) and use of Si foliar fertilizers (produced with conventional energy); Step 2: continuing crop straw recycling, soil application of synthetic ASi (produced with green energy) and use of Si foliar fertilizers (produced with green energy); Step 3: continuing crop straw recycling to build up a biogenic ASi pool that will replace the synthetic ASi pool in soils in the long-term, usage of Si foliar fertilizers produced with green energy. Consequently, the consumption of mineral fertilizers and the use of pesticides can be reduced stepwise. This figure was created using BioRender.com.

Another option to increase Si availability and ASi soil pool size is through the use of silicate-solubilizing bacteria99. Various types of silicate (e.g. quartz, magnesium silicate, and feldspar) have been reported to be solubilized by silicate-solubilizing bacteria (Bacillus sp., Burkholderia sp., Enterobacter sp., Rhizobium yantingense, Bacillus globisporus, Rhizobium tropici, Janthinobacterium sp., Acidobacillus sp., Pseudomonas stutzeri, and Aminobacter sp.)100,101,102,103,104,105. Silicate-solubilizing bacteria employ different mechanisms, involving pH reduction by inorganic and organic acids, chelating metabolites, exopolysaccharides, and ligands106,107,108,109,110,111. The release of both organic and inorganic acids by silicate-solubilizing bacteria further improves acidolysis.

Upon the restoration of ASi content and Si availability in agricultural soils to the high levels present in unaffected natural soils, this high level of reactive Si can be sustained by maximally closing the biogeochemical Si cycling by biogenic ASi (straw) recycling in the long-term23 (Fig. 5). The rebuilt of the biogenic ASi pool in agricultural soils by crop straw recycling might also represent a promising tool for the long-term sequestration of carbon and metal(loid)s (“heavy metals”) in these soils112.

Clearly, the pressure on transforming current agriculture towards more sustainable and resilient practices is high. In line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, the European Union has developed the farm-to-fork strategy with concrete targets for agriculture until 2030 as part of the European Green Deal113 and different countries in Europe such as Germany114 or Switzerland115,116 have developed national strategies, and policies towards these goals. Systems-based approaches are increasingly fostered117,118 and types of agriculture that build on comprehensive system approaches such as agroecology are of particular interest in this regard38. Yet, a more explicit consideration of ASi would further enhance the potential of such approaches.

Conclusions and implications for future research

In this Perspective, we have highlighted the potential of a Si-improved agriculture to produce resilient crops in a sustainable way, consistent with the goal to not surpass planetary boundaries6 regarding P resources and water availability. Nevertheless, there are several open questions concerning the economics, feasibility, and unintended negative consequences of re-establishing Si cycles in farming systems and agricultural landscapes. With current technologies, it is questionable if reactive Si can be brought to scale to ensure an equitable and fair use of Earth’s resources across world regions119. Critical knowledge gaps will require large investments in future research that should include the following aspects:

(1) Experimental approaches on the addition of reactive Si in the field, as well as experiments on fields with different initial availability of reactive Si have to be established. This is crucial to better understand the effects of reactive Si effects under a variety of field conditions.

(2) Observational and monitoring approaches, such as global and regular surveys of reactive Si in agricultural soils and its relation to farming systems performance are missing. This is important for broadening the database on the relationship between reactive Si and sustainable agricultural management.

(3) Synthesis studies mining available data on sustainability and resilience of agricultural systems in relation to the availability of reactive Si need to be performed. In parallel research is needed to evaluate how reactive Si can be brought to scale in farmers’ fields and larger agricultural landscapes and regions. Largely unknown, but important, is the effect of reactive Si on the availability of nitrogen (N), as only few data exist suggesting an increased N mobility due to reactive Si in peatlands120. In agricultural soils, the long-term application of straw (biogenic ASi) has been found to reduce the need for mineral N fertilization23.

(4) The effects of reactive Si on greenhouse gas emissions and soil carbon storage are not well understood yet, as most corresponding studies were performed using saturated soils providing contradicting results32,121,122.

Important research questions are: (1) How does the optimal amount of reactive Si vary across production environments and conditions to meet both goals of improved P and improved water availability? For soils with a large share of unavailable P, a strong increase in reactive Si may lead to P availability exceeding the needs of crops, potentially increasing the risk of P eluviation and subsequent eutrophication of aquatic systems. (2) What is the optimal amount of reactive Si for different soil types, management practices, crop types, and climatic conditions? (3) How do crop production systems need to be designed to ensure sufficient long-term availability of reactive Si. A considerably better understanding of the role of Si for sustainable and resilient crop production can be obtained by making use of the already existing wealth of data at the national, regional, and global level.

Responses