The unreliability of crackles: insights from a breath sound study using physicians and artificial intelligence

Introduction

Breath sounds manifest with varying pitches, durations, and characteristics depending on the pathophysiologies affecting airflow within the respiratory tract. Abnormal breath sounds are observed in over 25% of adults upon auscultation, with prevalence increasing with age1. Auscultation thus serves as a valuable tool for diagnosing and assessing the disease severity in a real-time, non-invasive, and cost-effective manner. While studies have validated its reproducibility and reliability2,3,4, the inter-observer agreement of breath sounds remains uncertain and heavily reliant on physicians’ experience5,6. Additionally, physicians’ preferences and auscultatory skills contribute to classification discrepancies7,8. Consequently, the clinical importance of conventional auscultation is waning. Luca Arts et al. conducted a meta-analysis on the diagnostic accuracy of lung auscultation, suggesting its limited contemporary role and advocating for its replacement with superior diagnostic modalities such as ultrasound or radiography9.

Nevertheless, advancements in technology have revitalized auscultation by facilitating more consistent differentiation of breath sounds. The advent of digital stethoscopes offers enhanced resolution and noise cancellation. They inherently excel in sound acquisition compared to traditional bell and diaphragm stethoscopes, particularly for high-frequency sounds like wheezing10,11. Spectrograms provide visual assistance, enhancing breath sound classification and increasing inter-rater agreement12,13. Crucially, the rapid progress of machine learning has significantly enhanced the accuracy and objectivity of breath sound analysis8,14.Through spectrogram and digital analysis, we gain a better understanding of adventitious sounds: wheezing presents as high-pitched and “musical” sounds, typically lasting more than 100 ms with a dominant frequency of 400 Hz or higher15,16. In contrast, crackles are discontinuous and explosive, with durations less than 20 ms and frequencies ranging from 60 to 2000 Hz16,17.

It is widely acknowledged that human subjectivity impedes auscultation. Bohadana et al. observed that physicians’ ability to describe lung sounds was superior for wheezes compared to crackles7. Whether the characteristics of adventitious sounds themselves contribute to classification difficulties remains unclear. Moreover, the robustness of deep learning models against different sound characteristics remains uncertain. Therefore, we established a database with breath sounds recorded in clinical field. By exploring the database with both conventional medical expertise and contemporary deep learning methodologies, our study aims to evaluate the difference in the identification ability of different breath sound.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

This cross-sectional comparative study was conducted at the emergency department (ED) of the National Taiwan University Hospital Hsinchu Branch, a tertiary medical center with an average of 5000 monthly ED visits, between January 2021 and February 2022. Non-trauma patients aged over 20 years presenting to the ED were eligible for inclusion. Exclusion criteria comprised pregnant individuals, patients experiencing out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, those transferred to another medical facility, or those discharged against medical advice.

Outcomes

The outcome was the efficacy of the initial labeling physician and All-data AI model in the identifying different breath sounds. The sensitivity, specificity, and area under the receiver-operating characteristic (AUROC) curve were calculated. The definition of wheezing and crackles are inherently subjective. Hence, we considered there is still a gold standard but it should be determined by physicians with a majority rule.

Data collection

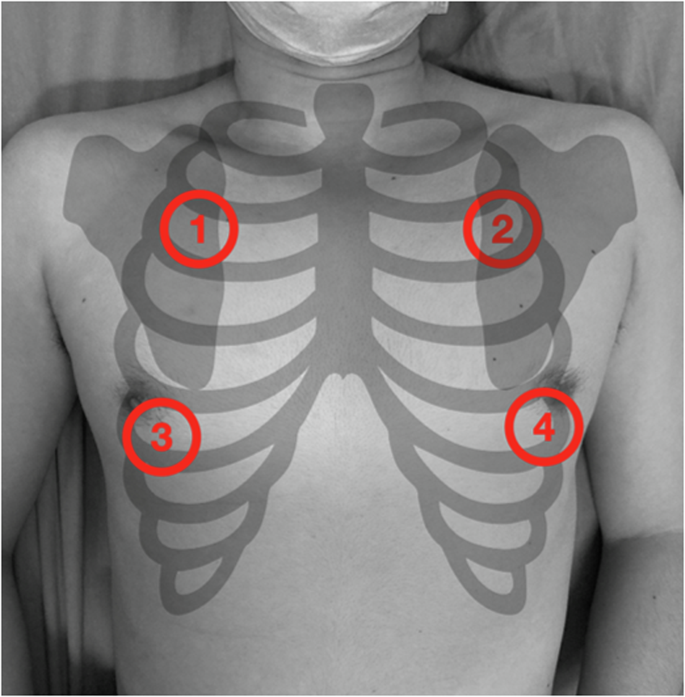

Patients’ breath sounds were recorded at the ED with fidelity, including possible noises. Recording was performed using a CaRDIaRT Electronic Stethoscope DS101, with a frequency range from 0 to 8000 Hz. The 20-1000 Hz are specifically highlighted. We exported soundwaves into digital formats as “.wav” format at 16-bit depth, resampled all recordings into 16 kHz, and converted them into mel-spectrograms. A 10-second recording of breath sounds was obtained from four sites on both lungs. The upper sites were located at the midclavicular line of the second intercostal space, while the lower sites were located at the anterior axillary line of the inferior scapular rim (Fig. 1). Since each recording is exactly 10 seconds long, no partitioning or segmentation was performed.

Auscultation recording was acquired at 4 sites of both lungs. The upper sites were located at the midclavicular line of the second intercostal space (area 1, 2), and the lower sites were at the anterior axillary line of the inferior scapular rim (area 3, 4).

The recordings were then uploaded to the online database “Formosa Archive of Breath Sound,” with no post-processing or filtering applied. Each recording was assigned to a physician for labeling, who was blinded to the patient’s clinical information. Physicians were allowed to replay the recordings multiple times and adjust the volume before labeling. Respiratory sound records from different chest locations of the same participant were presented concurrently during labeling. Breath sounds were categorized into five groups: normal, wheezing, crackles, unknown, and no breath sounds. Normal breath sounds were defined as unremarkable inspiration and expiration without adventitious sounds. Wheezing was characterized by high-pitched, “musical” sounds heard during either inspiration or expiration. Crackles were described as non-musical, brief, explosive sounds primarily occurring during inspiration18. Breath sounds were labeled as unknown if they could not be classified as wheezing or crackles but exhibited distinct inspiratory and expiratory phases. Recordings containing only ambient noise were labeled as no breath sounds. A pre-training course was provided for the labeling physicians to ensure inter-rater reliability. The pre-test demonstrated an acceptable Kappa value of 0.7 on the demo recordings.

Each breath sound was labeled by a single physician, with a total of five physicians involved in labeling the recordings. Additionally, six artificial intelligence (AI) breath sound interpretation models were developed: five AI models emulating the physicians, trained with their respective labeling data (referred to as AI doctors), and a final model trained with all available data (referred to as the All-data AI model). Every breath sound was then labeled by five AI doctors and the All-data AI model again. To ensure the robustness of labels in our database, labels were examined by three tests: physician’s label, the All-data AI model’s label and the majority opinion of the five AI doctors. Any discrepancy among these three tests would be considered as doubtful. Through above measures, we tried to identify as many doubtful labels as possible. Doubtful labels were then reassessed by two additional human physicians. The final label, determined by a majority rule among the three physicians (the initial labeling physician plus two additional physicians), served as the gold standard.

Model training

Based on the successful utilization of Mel spectrograms in breath sound classification as demonstrated in prior literature, all breath sound recordings underwent conversion into Mel spectrograms to facilitate efficient feature extraction and input5,19,20. Our model was constructed based on CNN14, which has exhibited promising performance in audio tagging tasks21. To further bolster performance and generalizability, we fine-tuned the network utilizing pre-trained weights from AudioSet, a comprehensive audio dataset comprising 2,063,839 training audio clips sourced from YouTube.

In order to tackle the challenges posed by data imbalance and scarcity, we implemented various data augmentation techniques, including SpecAugment and Mixup, alongside employing a batch-balancing strategy (Appendix 2). SpecAugment applies random time and frequency masks directly onto the Mel spectrograms, thereby enhancing model generalizability22. Additionally, Mixup blends two spectrograms in random ratios, effectively broadening the training distribution and resulting in enhanced performance22. Furthermore, the batch-balancing strategy mitigates data imbalance by oversampling the minority class within each batch23. By incorporating these methodologies, we optimized our model’s accuracy and robustness in classifying respiratory sound recordings.

Statistical analysis

Dichotomous and categorical variables were presented as numbers (percentages). Sensitivity and specificity were calculated using standard formulas for a binomial proportion, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) estimated using the Clopper-Pearson interval method. The calculation was performed with a “one v.s. the others” approach (i.e., for wheezing, the calculation was performed comparing wheezing to non-wheezing cases). Comparison was conducted between the All-data AI model and the initial physician who labeled the breath sounds. Sensitivity and specificity comparisons were conducted using McNemar’s test, as all breath sound files were labeled by both physicians and the All-data AI model. The performance in differentiating breath sounds was evaluated using the AUROC. Comparisons of AUROC values were performed using the Delong test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Considering that breath sound recordings from the upper auscultation sites are clearer than those from the lower sites due to interference from the female breast, we performed the sensitivity analysis using recordings only from the upper chest. Moreover, a subgroup analysis by sex was also conducted. Finally, unweighted Cohen’s kappa was measured to evaluate the agreement between physicians and the All-data AI model. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), Python, version 3.8 (Python Software Foundation), and R software, version 4.4.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

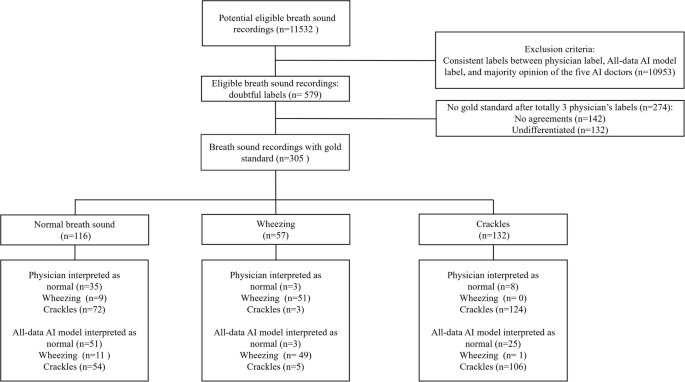

The Formosa Archive of Breath Sound has included 11,532 breath sound recordings at the time of writing, making it the largest breath sound database in Asia and one of the few databases dedicated to audio recording in clinical setting. Among them, there are 978 recordings of crackles, 277 recordings of wheezing, 4247 recordings of normal breath sound. Comparison of demographics between different breath sounds was not performed as a single patient could present with different breath sounds at various chest sites. Each of the 11,532 sound files was initially labeled by one of the five human physicians. Following the labeling by physicians and AI interpretation, 579 doubtful labels requiring further evaluation were identified. These doubtful labels were relabeled by two additional physicians, who were randomly selected from the rest four physicians. After a majority vote, those with undifferentiated or non-conclusive agreements were excluded. Ultimately, 305 final labels with definitive classifications (normal, wheezing, or crackles) were established as the gold standard. Among the 305 recordings, there were 199 patients and their characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age was 68.8 years, and 105 (52.76%) patients were male. 19 (9.55%) patients have congestive heart failure. 11 (5.53%) patients have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 13 (6.53%) patients have asthma. The distribution of labels from physicians, the All-data AI model, and the gold standard are displayed in Fig. 2 and further illustrated in a confusion matrix (Supplementary Figure 1, Appendix 1). Notably, we found that many normal breath sounds were misclassified as crackles by both physicians and the All-data AI model.

Flow of data through the study.

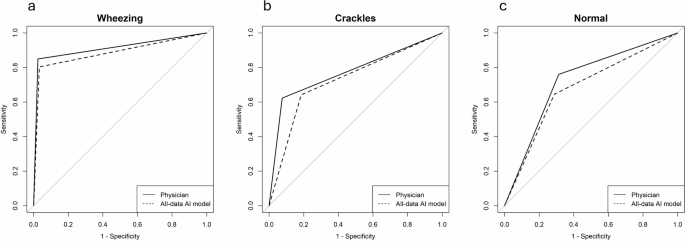

Based on the 305 gold standard labels, a comparison of breath sound identification ability was conducted between the All-data AI model and the initial physician who labeled the breath sounds. For calculation of sensitivity and specificity, contingency table was provided (Supplementary Table 1, Appendix 1). The result was shown in Table 2: For wheezing, both human physicians and the All-data AI model exhibited good sensitivities (89.5% vs. 86.0%, p = 0.480) and good specificities (96.4% vs. 95.2%, p = 0.248). There was no significant difference observed in AUROC between the two (0.951 vs. 0.934, p = 0.438) (Fig. 3a). Regarding crackles, both human physicians and the All-data AI model demonstrated good sensitivities (93.9% vs. 80.3%, p = 0.001) but poor specificities (56.6% vs. 65.9%, p = 0.023). Again, there was no significant difference noted in AUROC between the two (0.728 vs. 0.721, p = 0.168) (Fig. 3b). For normal breath sound, both human physicians and the All-data AI model exhibited poor sensitivities (30.2% vs. 44.0%, p = 0.020) but good specificities (94.2% vs. 85.2%, p = 0.002). No significant difference in AUROC was observed between them (0.698 vs. 0.695, p = 0.334) (Fig. 3c).

No significant difference of AUROC was noted between physician and All-data AI model for wheezing, crackles and normal breath sound. 3a. Wheezing 3b. Crackles. 3c. Normal breath sound.

The results of subgroup analysis by sex are presented in Supplementary Table 2a and 2b. For both male and female, subgroup analyses demonstrated a higher AUROC for wheezing compared to crackles, consistent with our main findings. No significant difference in AUROC was found between human physicians and the All-data AI model, except for crackle identification in female patients. Furthermore, after excluding breath sound recordings from the lower chest, 180 gold-standard recordings remained for the sensitivity analysis. The result was shown in Supplementary Table 3. The AUROC for wheezing identification remained above 0.9, while the AUROC for crackle identification stayed between 0.7 and 0.8. Lastly, Cohen’s kappa was calculated to evaluate the agreement between human physicians and the All-data AI model. In wheezing identification, the Kappa value was the highest at 0.948 while for crackles and normal breath sound identification, the Kappa values were only fair to moderate (0.516 for crackles and 0.298 for normal breath sound) (Supplementary Table 4, Appendix 1).

Discussion

Our study established the first breath sound database in the emergency department setting with clinical fidelity. Through double examination by both human experts and a deep learning model, the breath sound database was provided with relatively robust labels. Auscultation has long been criticized for its susceptibility to subjectivity and the observers’ abilities, which limits its clinical utility7,9,24. While an increasing number of studies attempt to address these issues with artificial intelligence25, it should be noted that different breath sounds not only influence human perception differently but also present varying complexities in signal processing and pattern recognition for machine learning. This study yielded two major findings: firstly, compared to wheezing, the identification of crackles proves to be more challenging and less prone to reaching a consensus. Secondly, despite employing multiple versions of deep learning models and adjustments in data sizes, the performance of crackle identification by deep learning still fell short compared to wheezing. Other auscultatory findings, such as heart murmurs, have been reported to exhibit good sensitivity and specificity, with AI achieving an AUC of 0.92 in detecting structural murmurs26. Therefore, despite a fair AUROC, crackles remain unreliable for its low specificity, low inter-rater agreement, and potential for confusion with normal breath sounds. Further examination is warranted for accurate diagnosis and proper management.

Our results are consistent with prior studies indicating that crackle identification is more inaccurate and unreliable than wheezing.6,7,12,24,27. The high-pitched musical tonal quality and longer duration of wheezing render it more distinctive and easier for human recognition compared to crackles, which are discontinuous and transient7,28. Additionally, louder background breath sounds also hinder the perception of crackles, particularly the coarse ones29. Previous studies have emphasized the importance of standardized terminology, auscultation training, and advanced equipment for improved breath sound classification6,7,11,24,28. A unified definition with common terminology can mitigate bias stemming from personal preferences or cultural differences, a factor crucial for crackles given its varied and vague manifestations.

In machine learning, our findings that wheezing identification rates surpass those of crackles are consistent with prior researches5,30,31,32. Emmanouilidou et al. developed signal processing tools for the analysis of pediatric auscultations and found crackles to be more difficult to discriminate. From a signal processing perspective, the frequency of crackles is ill-defined and may overlap with wheezing. Its short duration comprises only a small proportion of the signal, rendering it susceptible to contamination by normal segments between crackles32. Previous studies have also indicated that crackles are more challenging to locate in the breath cycle or signal duration due to their brief existence. Shanthakumari’s study confirmed that wheezing differs more from normal breath sounds compared to crackles in most first-order statistical features33. In summary, the difficulty in crackle detection stems from a low signal-to-noise ratio, crackle-like noise artifacts, and irregular loudness34.

As shown in Table 2 and the confusion matrix, there were many normal breath sounds misclassified as crackles for both physicians and All-data AI model. This explained the high sensitivity of crackles and the high specificity of normal breath sounds. Other machine learning studies have also indicated that crackles are more likely to be confused with normal lung sounds35,36. Notably, our study recorded the breath sound with an electronic stethoscope. Peitao Ye, et al. had suggested that electronic stethoscope is prone to producing false crackles, potentially interfering with medical decision-making37. However, their definition of normal breath sounds was based solely on the fact that they came from healthy individuals, without further examination to rule out any pulmonary pathologies. Especially crackles is reported to be the most frequent adventitious sounds in healthy people38. Finally, the study recruited patients from ED. Since patients are assumed to be ill to visit the ED, there may be a subconscious effect that lower the physicians’ thresholds to diagnose adventitious breath sound.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the inclusion of 579 breath sound files categorized as doubtful arose from discrepancies between physicians’ labels and AI interpretations. Thus they were more ambiguous and much harder for classification essentially. Secondly, breath sound labeling was conducted by emergency physicians rather than pulmonologists. Although researches on the association between medical specialty and the ability to identify different breath sounds has yielded inconsistent results, we acknowledge that labeling physicians from a single specialty could be a limitation of our study, given their specific training and cultural practices6,27,28,39. Third, our breath sound files were recorded in ED environment and contaminated by ambient noise. Nevertheless, this setting offers a more clinically realistic scenario. Fourth, despite having fewer samples for wheezing, both human physicians and the All-data AI model demonstrated better wheezing recognition. This further strengthens our results, as fewer samples typically lead to poor machine learning training. Lastly, the use of Mel spectrogram as input may have contributed to the similar performance of the All-data AI model to human experts16,40. However, the current model was trained with our breath sound database, which comprises relatively large datasets and exhibited fair performance. Overall, while machine learning increasingly serves as a black box model for accomplishing more complex tasks, the decision-making process is often challenging for explanation and understanding by physicians41. Our study not only compared breath sound classification between humans and machines in different breath sound but also contributed to a better understanding of the black box model.

Conclusion

Both human physicians and deep learning model exhibited superior performance in identifying wheezing compared to crackles or normal breath sounds, indicating shared weaknesses in the classification of these categories. Therefore, medical decisions based on crackles should be made with caution and confirmed through additional examinations. For AI training, greater attention should be given to distinguishing between crackles and normal breath sounds (Table 3).

Responses