Three-dimensional interaction between Cinnamomum camphora and a sap-sucking psyllid insect (Trioza camphorae) revealed by nano-resolution volume electron microscopy

Introduction

Plants harvest energy from the sun through photosynthesis to produce organic compounds, making them the primary producers in most ecosystems1. The phloem vascular tissue, which has an important function in plant growth and development, is the main pathway for long-distance transport of nutrients from source to developing sink organs2,3. Most phloem-feeding insects, belonging to the Hemiptera order, exhibit a distinctive feeding behavior observed in planthoppers, leafhoppers, and nearly all Sternorrhyncha species including whiteflies, aphids, mealybugs, and some psyllids2,4,5,6. This feeding adaptation evolved over more than 350 million years7,8. As a defining evolutionary trait, these insects have developed highly modified piercing-sucking mouthparts called stylets which are modified mandibles and maxillae, that travel from the plant cuticle, epidermis, and mesophyll tissues to access the nutrient-rich phloem sieve elements2,4,5,9,10,11. When the stylets pierce a phloem sieve element (SE), the plasma membrane lesion must be rapidly sealed by depositing callose and proteins to prevent leakage of phloem sap into the apoplast11,12. During penetration, Hemiptera insects deposit beads of rapidly gelling saliva to form a flange at the leaf surface (to limit stylets slippage) and a salivary sheath around the stylets that insulates the stylets from apoplastic defenses, respectively1,11,13. The salivary sheath remains in the plant after stylets withdrawal and thus enables us to microscopically follow the pathway of the stylets tip towards vascular bundles14,15.

Due to the efficient feeding pattern with stylets, most plant viruses are transmitted by Hemipteran insects, such as aphids, leafhoppers, planthoppers, whiteflies, mealybugs1,16,17 and the citrus huanglongbing pathogen Candidatus liberibacter (Proteobacteria) by the citrus psyllid Diaphorina citri18,19,20. Many attentions have been paid to the interactions of plants with whiteflies or aphids by now. Although both of them feed with stylets in multi-branched sheath paths, their feeding biology is very different. Aphids puncture and taste nearly every cell on the pathway to the phloem17,21, whereas whiteflies rarely piercing a cell before they establish phloem feeding sites1,8,11,22,23. Over the past decade, tremendous progress has been made in broadening our understanding of phloem–insect interactions. Integration of the tools of genetics, genomics, and biochemistry provides new approaches for identifying signaling pathways and mechanisms at the molecular level1,22,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. However, very less visible morphological details are available about the response of plant cells during insects exploiting the phloem tissue and how mouthpart structure relates to the function5. Knowledge about the fine structural changes of leaf tissues and mouthparts of Hemiptera internal structures are restricted to studies that are based on some discrete images by either light, confocal, or electron microscopy10,20,31,32,33,34,35,36. Volume electron microscopy (vEM), which is one of the seven Nature’s pick technologies that are poised to have an outsized impact on science, describes a set of high-resolution imaging techniques to reveal the 3D structure of cells, tissues and small model organisms at nanometre resolution37,38. Scientists have revealed several 3D structures with this technology, such as the pericardial nephrocytes in Drosophila39, the detailed structure for a whole brown planthopper10 and the entire brain of the larva of the Drosophila40.

The camphor psyllid (Trioza camphorae, Hemiptera: Psyllidae) infests the lower face of Cinnamomum camphora leaves, leading to the formation of visible pit galls on the leaves (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1). Some histological analyses with light microscopy have suggested hypertrophied epidermal cells and increased phloem areas as primary convergent processes in gall formation41,42,43,44. In this study, we applied vEM to present a detailed 3D structure of the interaction mode between the plant and the phloem-feeding Trioza camphorae at nanometre resolution. The psyllid stylets penetrate each cell on the way to the sieve tube, and the plant cells form new cell wall around the stylet bundle. Our vEM reconstruction results provide convincing evidence of significant decreases in plant cell volume and drastic increases in plant cell layers within the pit galls. Global transcriptomic profiles in infested leaves compared to non-infested ones reveals some up-regulated genes associated with cell wall thickness and cell replication, confirming our reconstruction results in molecular level. 3D structures involved in the feeding process of the stylets on plant leaves are also proposed. As phloem-feeding insects pose significant economic threats worldwide and remain challenging to understand due to their specialized feeding strategies5, understanding these structures with innovative vEM technique will be a key step towards a conceptual framework of phloem–insect interactions and mitigating the global destruction caused by phloem feeding pests and diseases.

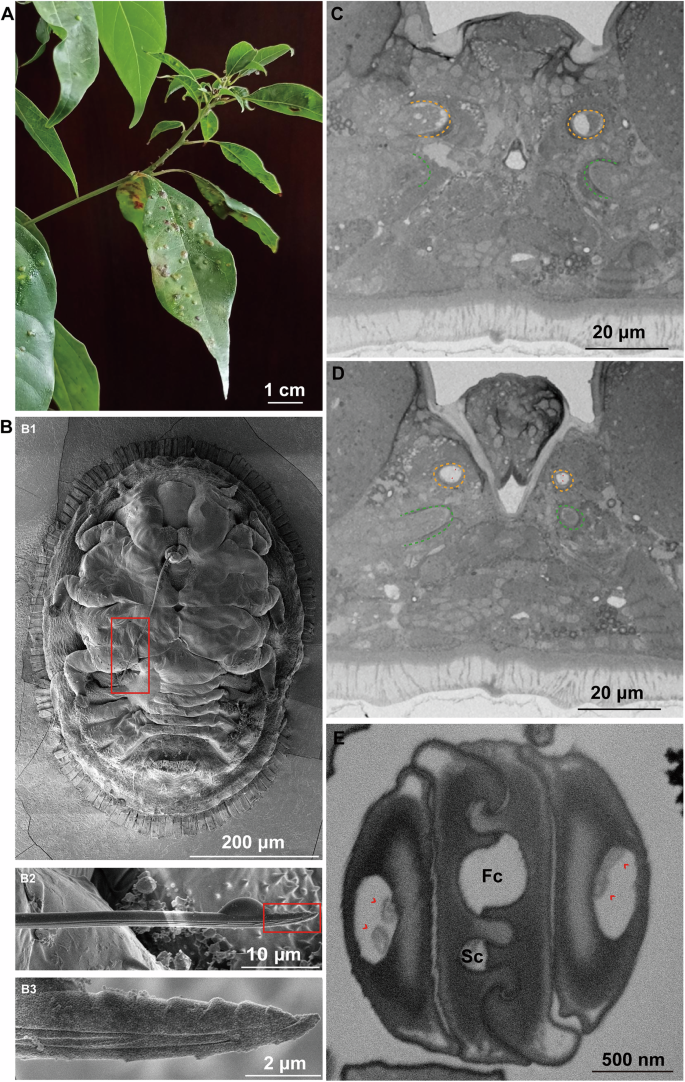

A Pit galls formed by Trioza camphorae nymphs on Camphor tree leaves B SEM images of the Trioza camphorae. Image (B2) which shows the stylets is zoom in of the red box in (B1), and image (B3) is zoom in of the red box in (B2). C–E Cross sections of the stylets shown by 2D images. C–E represent sample images from the stylets base to the distal end, respectively. Yellow and green dash lines indicate the mandibular and maxillary stylets, respectively. Red arrowheads point to the dendrites. Fc food canal, Sc salivary canal.

Results

Structure and feeding mechanism of T. camphorae stylets on plant leaves

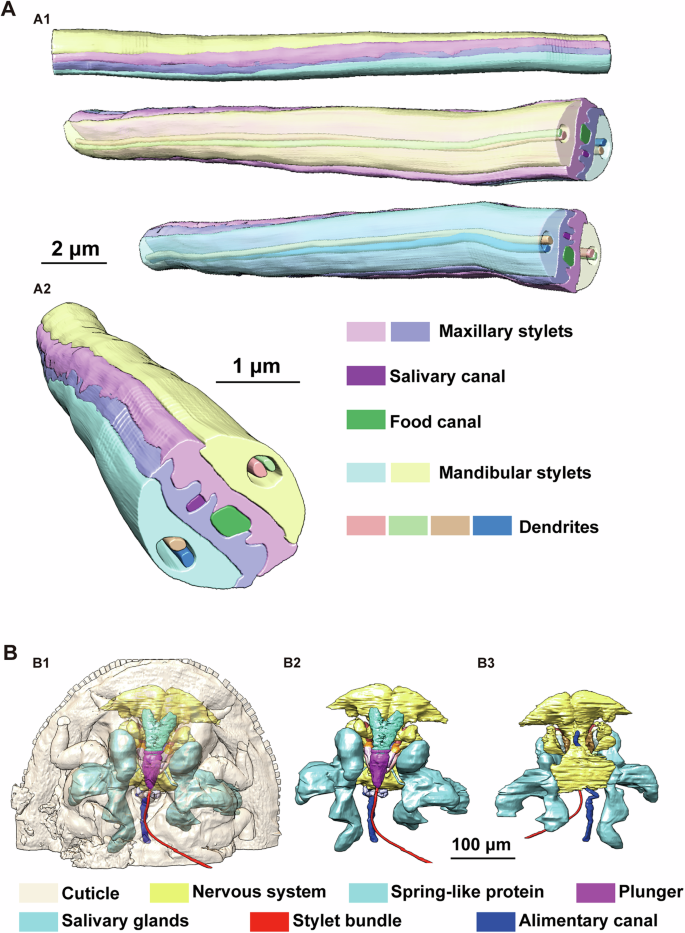

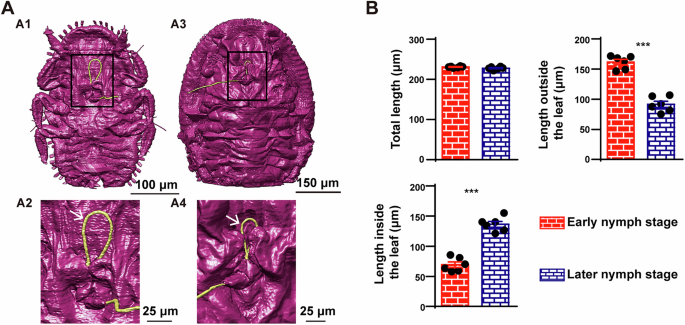

T. camphorae is an important pest that severely damages the camphor tree, leading to the formation of visible pit galls (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1). A series of serrate ridges extend along the distal of the mandibular stylets on the lateral surface, which probably helps the stylet bundle penetrate and fasten in plant tissues (Fig. 1B). Notably, the base of the stylets contains numerous neuron bodies, while only two dendrites are present at the apex (Fig. 1C–E). Internally, the maxillary stylets are equipped with a series of ridges and grooves to form an interlocking system: dorsal, middle and ventral locks. The food canal (Fc) through which plant sap is sucked up into the psyllid esophagus is situated between the dorsal and middle locks. The salivary canal (Sc) that directs saliva into the plant runs ventrally to the food canal and is separated by apposed ridges on the two contiguous maxillary stylets (Fig. 1E). Based on the reconstruction of serial sections, the thin stylet bundle of camphor psyllid is a long flexible tube formed of two maxillary stylets enclosed by a pair of mandibular stylets, each of which has an unbranched dendrite canal housing 2 dendrites that run throughout the length of the stylets (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, neither the maxillary nor the mandibular stylets are directly connected in parallel to the main nervous system. Instead, they are controlled in series by the nervous system (Supplementary Fig. 2A). The 3D structures involved in sap-sucking are depicted in Fig. 2B, providing an overview of the relative position of various structures in three dimensions. These include the stylets, the sucking pump components such as the spring-like protein and the plunger, muscles located at the base of the stylets, as well as the salivary glands and the alimentary canal. Unlike whiteflies, where the stylets may remain coiled within the nymph’s body if the total length is not necessary to reach the phloem tissue35, our study reveals that the stylet bundle is coiled outside the body of T. camphorae nymphs (Fig. 3A). To examine whether the stylet bundle grows with the nymph’s development, we reconstructed and calculated the total length of the stylets in both early (first instar) and later (the 3rd instar) nymphs. Interestingly, while the total length of the stylets showed no significant difference between stages, much longer stylets were found inside the leaf tissue as the nymphs progressed in growth (Fig. 3B).

A 3D reconstruction of the stylet bundle. (A1), side view of a section of the stylets with or without transparency of mandibular styles. (A2), cross section of the stylets. B Overview of the 3D structures involved in feeding process of the stylets on plant leaves. (B1, B2) Ventral view, (B3) Dorsal view. Some obvious elements are labled in corresponding color.

A Reconstructions of external surface in both early and later nymphs. (A1) and (A2) show the ventral view of an early nymph. (A3, A4) show the ventral view of a later nymph. (A2, A4) are zoom in of the black box in (A1, A3), respectively. White arrows point to the stylets (yellow) coiled outside the body. B Statistical analysis of the length of the stylets in both early and later nymphs. The length of the stylets was visualized as mean ± SEM and analyzed by Unpaired t-test (n = 6 biologically independent samples), ***p < 0.0001.

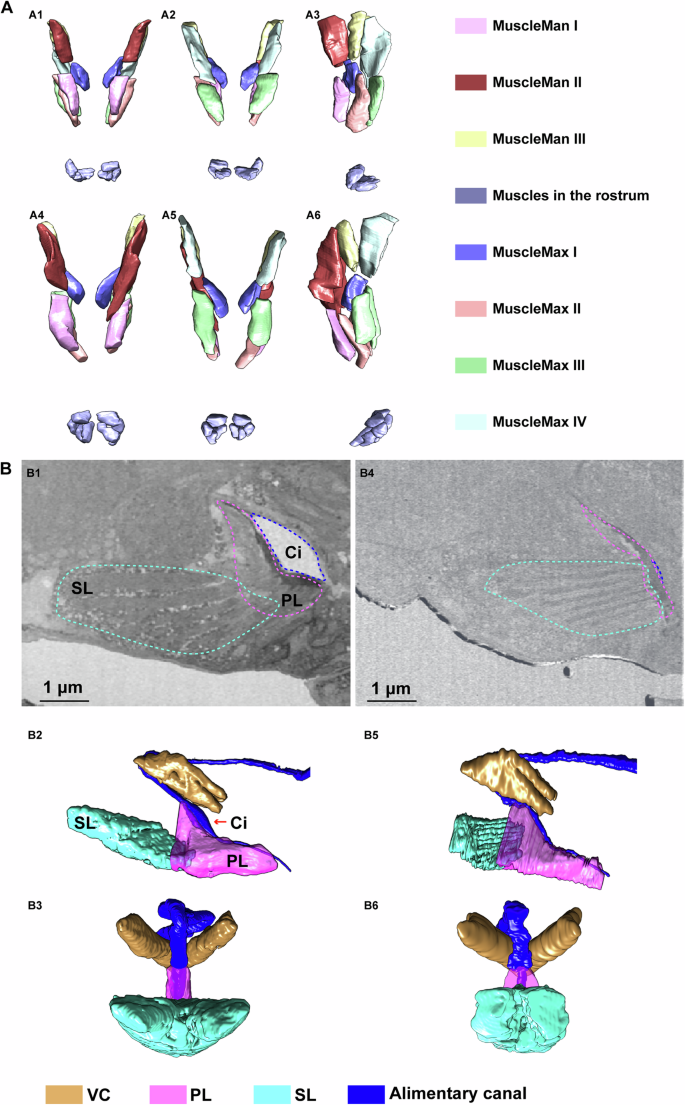

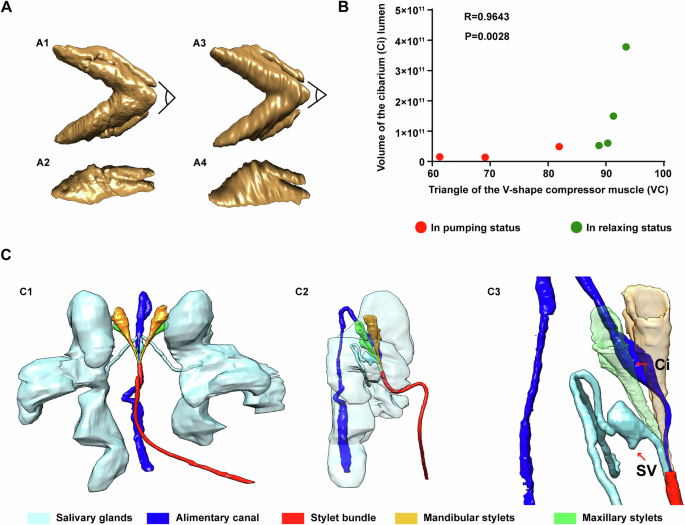

To delve deeper into the feeding process of the T. camphorae stylets on plant leaves, we initially examined the musculature potentially involved in the feeding process using two nymph samples in either feeding or relaxing status (Figs. 4, 5A). Seven pairs of muscles were identified at the bases of the stylets (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 2B), with three pairs responsible for the mandibular stylets (MuscleMan I-III) and the remaining pairs for the maxillary stylets (MuscleMax I-IV). During feeding, these muscles are long and thin compared to their relaxed state (Figs. 4A–6). When the muscles contract to protract the stylets, the stylets stretch out through the rostrum to explore the leaf tissue. And muscles in the rostrum likely dictate the directions. Once the stylet bundle reaches the phloem, fluids are first imbibed through the food canal by turgor pressure45,46,47 into the cibarium which is the extreme anterior end of the esophagus, and then propelled into the esophagus by the sucking pump located in the head. The four-part sucking pump in T. camphorae consists of a spindle-shaped cibarium (Ci) covered by a flexible plunger (PL), a spring-like protein (SL) extending from the head capsule to the plunger, and a dorsal V-shaped compressor muscle (VC) that moves anteroventrally to compress the cibarium lumen upon contraction (Fig. 4B). During the pumping action, the contracted spring-like protein pushes the plunger towards the ceiling of the cibarium, while the contracted V-shaped muscle compresses the cibarium, facilitating the pumping of fluids into the esophagus. Moreover, we observed that the angle of the V-shaped muscle appeared to decrease during pumping (Fig. 5A). Subsequently, we reconstructed additional V-shaped muscles and cibarium from six individuals in either pumping or relaxed status to calculate V-shaped angles and volumes of the cibarium for statistical analysis. Statistical analysis revealed a positive correlation between the V-shaped angle and cibarium volume (P = 0.0028), suggesting that smaller angles correspond to smaller volumes (Fig. 5B). Understanding the functional interaction between the sucking pump and the stylets is crucial for elucidating the feeding behavior of sap-sucking insects in general. Additionally, since saliva produced in salivary glands is essential for sap-sucking and mediating interaction between the insect and the plant, we also reconstructed the salivary glands along with their core component structure, the salivarium (SV)10. Saliva produced in the salivary glands eventually flows into the Sc in the stylet bundle through the pocket-like salivarium (Fig. 5C).

A 3D structure of muscles in charge of the stylets. (A1–A3): in relaxed individual; (A4–A6): in feeding modality. (A1, A4), ventral view; (A2, A5), dorsal view; (A3, A6), side view. B Reconstruction of the sucking pump in the head. (B1–B3) show sucking pump in relaxed individual. (B4–B6) show sucking pump in feeding modality. (B1, B4) are cross sections of the sucking pump showed by 2D images. Dash lines indicate the corresponding elements bellow. (B1, B2, B4, B5) are side view. (B3, B6) are rotated ninety degrees counter-clockwise from (B2, B5), respectively.

A 3D structure of the V-shape compressor muscle. (A1, A3), ventral view, (A2, A4), side view. (A1, A2) show VC in relaxed individual. (A3, A4) show VC in feeding modality. B Correlation analysis of the V-shape angle and the cibarium volume. Data were computed with nonparametric Spearman correlation. Spearman r = 0.9643 and P = 0.0028. C The relative position of the salivary glands and the alimentary canal. (C1), ventral view, (C2), side view with transparency of the salivary glands, (C3), zoom in of (C2) to show the relative position of the salivarium (SV) and cibarium (Ci).

Cellular responses of interaction between plant and the insect

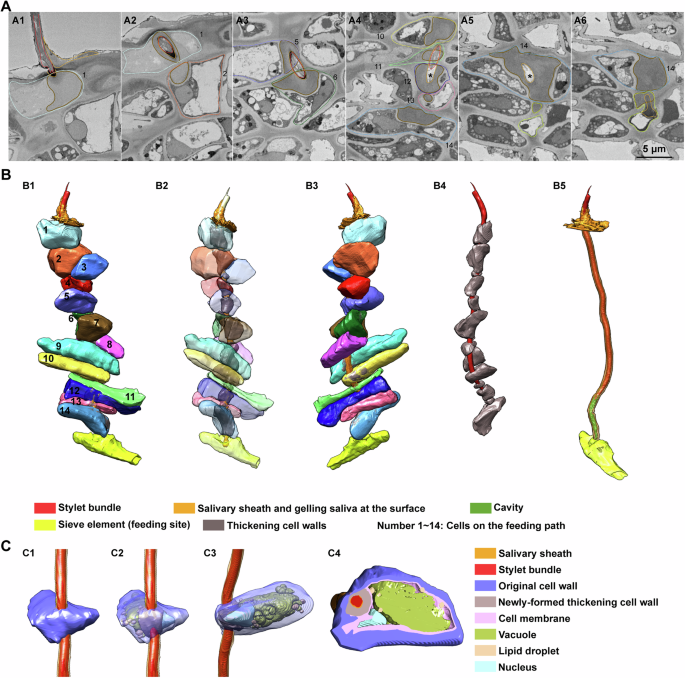

While our understanding of plant responses to Hemipteran insects primarily resides at the molecular level, details at the cellular level remain relatively elusive. In pursuit of deeper insights, we captured high-resolution images of leaf tissues during the exploitation of phloem tissue by the stylets (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Video 1). Notably, we observed a smear of gelling saliva on the leaf surface, and reconstructed cells penetrated by the stylets from the lower epidermis to the upper epidermis (Fig. 6). To our surprise, T. camphorae feeds with stylets in a branchless sheath path to the phloem tissue, which is different from the assumed multi-branched sheath paths observed in both aphids and whiteflies (Fig. 6A, B). The stylets ultimately puncture an elongated sieve element and start to feed on (Fig. 6A6, the cell surrounded by yellow dash line). Intriguingly, the stylets penetrate every cell on the way to the feeding site, wherein new cell walls form around the salivary sheath with the stylets wrapped inside, eventually fusing with the original cell walls to create remarkably thickening cell walls (Fig. 6A, B). Significantly, the penetrated cells laying from the lower cuticle to the phloem display no signs of shriveling or lack of nuclei, indicating their vitality (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, we discovered an irregularly shaped cavity formed by the gelling saliva at the end of the salivary sheath, adhering to the punctured sieve element (Figure 6A4, 6A5 and 6B5). The volume of this cavity, calculated across four samples is 19.69 μm3, 28.08 μm3, 16.88 μm3 and 33.97 μm3, respectively. This phenomenon suggests that the stylets rapidly secrete gelling saliva to prevent sap leakage into the intercellular space upon piercing the sieve element, subsequently retracting slightly. The cavity facilitates the flow of sap into the stylets, driven by turgor pressure. Additionally, we observed several empty paths of the salivary sheath remaining inside the leaf tissue at various depths relative to the lower cuticle surface, with only one deepest path reaching a shriveled sieve element inferred to be a former feeding site (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). This suggests that the stylets must be fully withdrawn and then reinserted into the leaf at a new penetration site, probing different cell contents to guide the stylets to the phloem through several cell layers. Reconstruction of phloem cells near the feeding site showed a deep exploration of phloem tissue by the stylets (Supplementary Fig. 5). The stylets passed through several sieve elements, companion cells and parenchyma cells at various cell layers before feeding. It’s important to note that the stylets ever puncture a sieve element (cell #13 in Fig. 6A4 and Supplementary Fig. 6) without stay before final arriving the choosing feeding site, indicating a persistent exploring until the “right” contents are detected. The fact that insects won’t necessarily start feeding as soon as they come across a sieve element, proposing a principle of right plant saps rather than short distance.

A Cross sections of the feeding path showed by 2D images. Dash lines and numbers indicate the corresponding cells on the feeding path in (B1). Continuous thin lines indicate stylets (red), salivary sheath (yellow) and newly formed thickening cell wall (brown), respectively. Black stars in (A4, A5) indicate the cavity. B Reconstruction of the cells penetrated by the stylets from lower epidermis to the feeding site. (B1), overview of the reconstruction from one side. (B2), view of the reconstruction with transparency of these cells. (B3) is rotated 180 degrees from (B1). (B4) shows the stylets and the thickening cell walls corresponding to the 14 cells in (B3). Penetrated cells are removed to highlight the cavity (green) in (B5). C Reconstruction of details inside the penetrated cell. (C1), overview of the reconstruction and the cell is numbered as 5 in (B1). (C2), view of (C1) with transparency of original cell wall. (C3), rotate image (C2) ninety degrees clockwise. Cell membranes in (C2, C3) are removed to present the inner details. (C4), an example cross section of the cell reconstruction.

Cellular responses during gall formation

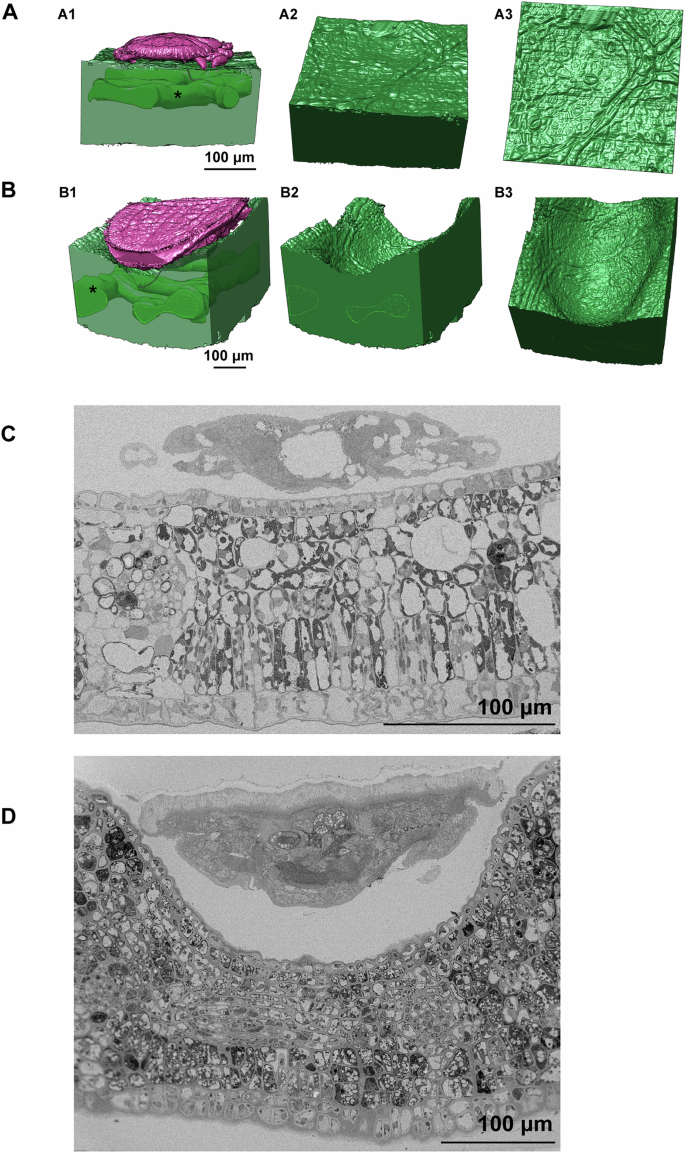

Many psyllids exhibit localized gall formation on the leaf lamina rather than along the leaf margin. T. camphorae, infesting Cinnamomum camphora, exemplifies this by forming pit galls48,49,50. Nymphs initially feed within shallow pits on the lower leaf surface. As nymphs commence feeding, they settle and become flattened against the leaf surface, resulting in small discolored bulging galls on the upper leaf surface (Supplementary Fig. 1). Previous discussions on gall tissue have relied on basic optical histological analyses. To gain deeper insights into the morphological details, we reconstructed both gall tissues and healthy leaf tissues, calculating the volumes of several series of cells located at the bottom and side wall of the gall for statistical analysis (Figs. 7, 8). During early nymph development, the shallow pit is not yet formed and discernible to the naked eye (Fig. 7A, C). The cell layers and volumes of all cell types, except the upper epidermis, exhibit no significant changes across various samples. However, the volumes of upper epidermis cells at both gall sites are significantly reduced, resulting in thinner leaf tissue at the gall bottom (Fig. 8A1–A3 and B). Subsequently, activated cell division is observed at the gall sites and the cell layers on the side wall increase drastically (almost three times compared to healthy leaf), contributing to the thickening leaf tissue constituting the bulging galls (Fig. 7B, D, Fig. 8B). However, despite this increase, the volumes of all cell types except the lower epidermis are significantly decreased (Fig. 8A4–A6 and 8B). At the gall bottom, where nymphs are appressed, the increase in cell layers is less drastic but still significant compared to healthy leaf tissue. Moreover, the volumes of cells at this site are significantly decreased, resulting in a thinner leaf thickness (Fig. 8B).

A Reconstruction of gall tissue and nymph in early nymph stage. (A1) View of the reconstruction from one side and black star indicates the vascular bundle. (A2), an oblique view of the leaf lower surface. (A3), intuitive view of the leaf lower surface. B Reconstruction of gall tissue and nymph in later nymph stage. (B1), view of the reconstruction from one side and black star indicates the vascular bundle. (B2), remove the psyllid in (B1). (B3), an oblique view of the gall. C Cross section of the leaf tissue infesting by psyllid in early nymph stage. D Cross section of the leaf tissue infested by psyllids in the late nymph stage.

A Reconstruction of series of cells in leaf tissues from the lower epidermis to the upper epidermis. (A1–A3), leaf tissues in early nymph stage. (A4–A6), leaf tissues in later nymph stage. (A1, A4) represent cells in leaf tissues without infestation (healthy leaf), (A2, A5) represent cells at the gall bottom (base of gall), (A3, A6) represent cells at the side wall of the gall (side of gall). B Statistic analysis related to gall tissues in both early and later nymph stages. These three groups of graph represent the comparisons of the cell volume in different leaf tissues (n = 3 biologically independent samples), the leaf thickness (n = 6 biologically independent samples) and the number of leaf cell layers (n = 3 biologically independent samples), respectively. Health leaf, Base of gall and Side of gall in the same nymph stage were analyzed for statistical significance using ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. The dataset of Health leaf was the control column in each comparison. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Proposed model of interaction between plant and the psyllid

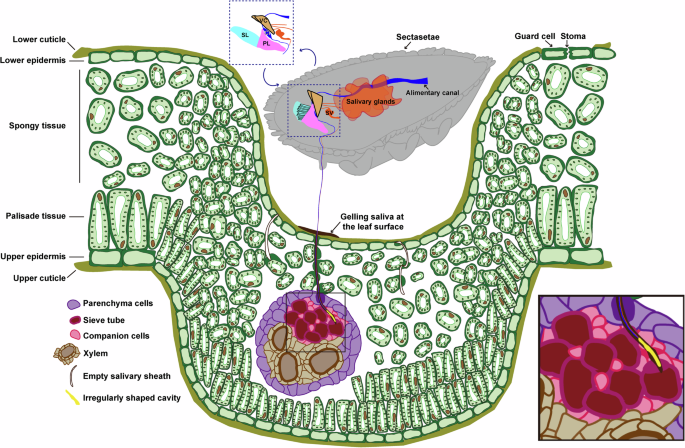

Through the meticulous reconstruction of the plant cells penetrated by the stylets along the feeding path and the examination of gall tissues at nanometer resolution, we have uncovered deeper insights into the plant cellular response to phloem-feeding insect. Our findings shed light on a morphological model of interaction between plant and the psyllid (Fig. 9). As the stylets initiate penetration, gel saliva is released onto the leaf surface, immobilizing the stylet bundle. Concurrently, as the stylets exploit the leaf tissue, saliva is secreted through the salivary canal, diffusing around the stylets to form a protective salivary sheath, shielding the stylets against plant chemical defenses. This study marks the observation of a branchless sheath path leading to the sieve tube in sap-sucking Hemipterans. Notably, all plant cells on the way to the feeding site are penetrated by the stylets, resulting in the remarkable thickening of cell walls. Additionally, the presence of an irregularly shaped cavity formed by gelling saliva adhering to the punctured sieve element suggests the retraction of the stylets post-penetration. It has been described that callose forms amorphous clogging deposits (papillae) at the sites of degraded plant cell walls to limit the penetration and spread of the fungal infections in Arabidopsis51,52. Rice leaves restrict phloem sap ingestion by the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens through callose deposition at the sieve plates53. Callose deposition has also been documented in various plant-aphid interactions. For example, in wheat leaves infestation by the aphids, a significant callose deposition is found in sieve plates, companion cells, stylet tracks or epidermal cells54,55. Moreover, infestation of barley with aphids results in callose deposition in epidermal cells and sieve plate pores56,57. In this study, the presence of thickening cell walls in penetrated cells, without signs of cell death, suggests a protective response, possibly due to callose deposition at puncture sites, limiting damage and sap outflow. Furthermore, activated cell division is observed in gall tissue and most of leaf cells exhibit a significant decrease in cell volume. The thickening leaf tissue is caused primarily by the drastic increase in cell layers rather than volume. The presence of several empty paths of the salivary sheath within the leaf tissue at various depths relative to the lower cuticle surface suggests the previous passage of stylets through these regions. Taken together, our study utilizing the innovative vEM technique, unveils the plant cellular morphological response at nanometer resolution, opening new perspectives in understanding phloem-insect interactions.

Proposed model of interaction between plant and the psyllid.

Discussion

Various psyllids are known to induce gall formation in their host plants, ranging from simple pit galls to more elaborate structures such as roll leaf galls or completely enclosed nipple gall36,48,49,58. The feeding behavior of T. camphorae nymphs within shallow pits on the lower leaf surface results in the formation of pit galls on the upper leaf surface48. Previous studies propose that hypertrophy of the phloem bundles is associated with galls induced by phloem-sucking Hemipterans42,43,59,60. The epidermal cells on both surfaces and the parenchyma cells are hypertrophied by calculating the cell area in leaf-rolling galls42. In our study, we observed activated cell division in pit gall tissue, along with a significant decrease in cell volume and a drastic increase in cell layers (Fig. 8B). This thickening of the leaf tissue in pit galls appears to be primarily due to hyperplasia rather than hypertrophy. Indeed, the volume of vascular bundle per 100 μm is significantly increased in pit galls (Supplementary Fig. 7A, B).

Furthermore, to gain insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying gall formation, we conducted high-throughput RNA sequencing of camphor leaves infested by T. camphorae (Supplementary Fig. 7C–F). Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed significant alterations in global transcriptomic profiles in infested leaves compared to non-infested ones (Supplementary Fig. 7C). A total of 1481 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are identified, comprising 964 upregulated and 517 downregulated genes. The gene WAT1, a determinant of cell wall thickness, and the histone gene associated with cell replication are the most significantly upregulated, while genes involved in defensive terpene synthesis and WRKY transcription factors are the most significantly downregulated. We identified 23 DEGs associated with plant hormone signal transduction (Supplementary Fig. 7D). Interestingly, half of these genes link to the auxin pathway, and the majority of them show significant upregulation upon T. camphorae infestation. Enrichment analysis demonstrate that the majority of upregulated genes are associated with chromosomes and associated proteins, DNA replication proteins, cytoskeleton proteins, flavonoid biosynthesis, and exosomes (Supplementary Fig. 7E). In contrast, genes related to beta-alanine metabolism, terpenoid and polyketide metabolism, peroxisomes, fatty acid degradation, and phosphatidylinositol signaling system are significantly suppressed (Supplementary Fig. 7F). These results suggest that T. camphorae infestation potentially activate plant cell proliferation while inhibiting plant defenses. During the gall development, a combination of cell division and cell growth occurs, which was primarily orchestrated by phytohormones61. For example, in galls formation on Rhus chinensis and R. javanica, auxin and cytokinin signalings were substantially activated62,63. Similarly, upregulation of auxin response genes was reported in the insect-induced gall of Hawaiian Metrosideros polymorpha64. While another gall-forming aphid-like parasite phylloxera, Daktulosphaira vitifoliae, interestingly induced stomata formation in proximity to the insect, promoting the assimilation and importation of carbon into the gall. The expression of genes associated with transportation of water, mineral and nutrient, glycolysis, and fermentation was upregulated in leaf-gall tissues65. In our study, the induction of GH3 auxin-responsive promoters, auxin-induced proteins, and auxin response factors (Supplementary Fig. 7D) strongly implicates auxin signaling as a key player in T. camphorae-induced gall formation. However, the precise mechanisms by which psyllid effectors modulate host auxin signaling require further investigation. Interestingly, the presence of marginal sectasetae (labeled as sectasetae in Fig. 9) around the body, observed in T. camphorae, is characteristic of typical pit galler morphology66. In contrast, the absence of these structures in the Asian citrus psyllid, despite its close phylogenetic relationship, results in the lack of gall development in infested plants18,19,67.

The active pumping mechanism for fluid intake evolves independently across arthropod lineages, yet all share a common functional principle: altering the volume of a chamber to force fluid in or out68,69. The fundamental pattern of the psyllid pumping chamber, formed by the cibarium, mirrors that of various insects with sucking mouthparts including those in the Hemiptera, Lepidoptera, Diptera, Siphonaptera, and Thysanoptera68,69,70,71,72. Previous studies have suggested that the volume of the pump chamber is regulated solely by dilator muscles or through coordination between dilator and compressor muscles10,68,69,70,71,72. In our study of psyllids, we reveal, in fine structural detail, the presence of a sucking pump, with only compressor muscles responsible for regulating the chamber’s volume (Fig. 4B). Contraction of the spring-like protein and the V-shaped muscle compresses the spindle cibarium, facilitating the pumping of fluids into the esophagus. Recent biophysical investigations have begun exploring these pumping complexes through the lens of biomechanical science [58, 62]. Further study of additional examples will enrich our understanding of this process.

The newly observed intracellular branchless feeding path of psyllids distinguishes them from the classical multi-branched models observed in aphids and whiteflies. Studies focusing on aphid feeding behavior suggest a model involving intercellular pre-programmed radial orientation of stylet progression via cell walls, intermittently punctuated by regular intracellular sampling toward the sieve elements2,15. In whiteflies, the highly branched salivary sheath formed by a single whitefly crawler in cleared sweet potato leaf demonstrates that the nymph is able to at least partially withdraw and reinsert its stylets bundle35. A previous study using scanning electron microscopy shows that in most cases the whitefly stylets intracellularly penetrate through the epidermal cell to continue intercellular penetration in mesophyll cells35. However, other researchers using Electrical Penetration Graph techniques and light microscopy proposed that whiteflies always start with intercellular penetration through the epidermis and mesophyll, while few intracellular punctures occur when the stylets bundle is close to the phloem8,73,74. Intriguingly, our findings using the volume electron microscopy (vEM) technique unveil a unique feeding pattern of psyllids, wherein the stylets penetrate every cell on the path to the feeding site, leaving behind an irregularly shaped cavity at the end of the gelling saliva adhering to the feeding sieve element (Fig. 6). The presence of multiple shallow or deep branchless salivary sheaths suggests considerable trial and error in reaching or changing feeding sites. The dead-end salivary sheath indicates complete stylets retraction, followed by the selection of a new penetration site on the leaf tissue (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

Sap-sucking Hemiptera’s feeding behaviors necessitate the ability to locate feeding sites buried deep within leaf tissues, yet our understanding of how stylets navigate to the sieve elements remains incomplete. Considering that sucrose in phloem sap is several-fold higher than in the cytosol of mesophyll cells75, it has been proposed that the brief punctures of epidermal and mesophyll cells by stylets help aphids locate sieve elements by sensing sucrose gradients76. Also, low pH in the probed cell sap is considered to be a stimulus for stylets retraction for aphids. They continue probing until appreciable sucrose concentrations and a neutral pH are sensed15. While during the migration of the whiteflies stylets, the intracellular punctures occur much less frequently compared to aphids73,74. Newly findings suggest that whiteflies may track increasing sucrose concentrations in leaves using sugar receptors to locate feeding sites2. We posit that psyllids may similarly use intracellular penetrations to sample contents of different cells, guiding stylets to the phloem tissue across several cell layers. Furthermore, our observations reveal that the base of psyllid stylets contains numerous neuron bodies, suggesting potential sensory functions related to pressure, sugar, pH, or ion concentrations (Fig. 1C–E). Although no opening is observed at the apex of mandibular stylets, neurons may detect these stimuli through other ways such as receptor molecules.

In conclusion, this study highlights a notable observation of a branchless sheath path leading to the sieve tube in sap-sucking hemipterans, revealing that plant cells respond to insect feeding by thickening cell walls. The thickening of leaf tissue during gall formation is attributed to cell hyperplasia rather than hypertrophy. Although feeding patterns with stylets vary among different phloem-feeding insects, similar cellular responses may occur in punctured plant cells. Enabled by the innovative vEM technique, these findings offer detailed visualizations of fine structural changes in plant cells and pit gall tissues, advancing our understanding of cellular responses to insect activity. The 3D structures of plant cells and the adaptations of stylets for specialized feeding strategies could even inspire novel concepts for tunnel excavation in bionics. Future research into the molecular mechanisms of gall formation may further aid in developing innovative control strategies against gall-inducing pests.

Methods

Insects and plants

The T. camphorae used in this study were originally collected at a camphor (Cinnamomum camphora) forest in Ningbo University (Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, China, E121°31’ N29°52’ in April 2023). They were maintained on camphor plants which had been transplanted from the forest to the green house under relatively constant environmental conditions.

Samples and preparation

T. camphorae infests on the lower part of Cinnamomum camphora leaves after incubation and pit galls are obvious at the 3rd instar. Taken this into consideration, we prepared T. camphorae and leaf samples to separately collect digital images of both early (first instar) and later (the 3rd instar) nymphs at a resolution high enough (65.11 × 65.11 × 100 nm) to reconstruct the muscles, nerves and glands. We also collected higher resolution (12.21 × 12.21 × 100 nm) images to reconstruct the stylets bundle and the leaf cells. The physiological activities of psyllids were stopped by dripping liquid nitrogen on the body. The samples were fixed for 24 h in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (TED PELLA, Lot No.: 2171002), and 0.003% CaCl2 (Sigma, C-2661-500G) in sodium cacodylate (Sigma, CAS: 6131-99-3) buffer (0.1 M). The tissue blocks were then washed in sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M) and treated with a solution containing equal volumes of 2% OsO4 (TED PELLA, Lot No.: 4008-160501) and 3% potassium ferrocyanide (Sigma, CAS: 14459-95-1) in 0.3 M sodium cacodylate with 4 mM CaCl2 for 1 h on ice. After rinsing with double-distilled water (ddH2O), the samples were incubated in 1% thiocarbohydrazide (Sigma, CAS: 2231-57-4) (in water) for 20 min at room temperature. Then the samples were rinsed with ddH2O (double distilled H2O, Merck Millipore, Milli-Q Reference System) and treated with 2% aqueous OsO4 for 30 min at room temperature. The tissue blocks were washed in ddH2O and immersed overnight at 4 °C in 1% aqueous uranyl acetate. After washing with ddH2O, the samples were incubated in 0.66% lead nitrate (Sigma, CAS: 10099-74-8) diluted in 0.03 M L-aspartic acid (Sigma, CAS: 56-84-8) (pH 5.5) for 30 min at 60 °C, then dehydrated in an ascending ethanol series and flat-embedded in EPON 812 resin (EMS, cat. no: 14900) for 48 h at 60 °C10.

Data collection

Resin blocks were trimmed using a Leica EM trimmer, until the surface of the black tissue in the block could be observed. Next, resin blocks were glued on a stub with electrically conductive colloidal silver (TED PELLA, Lot No.: 169773610), followed by coating with about 30 nm platinum using a sputter coater (Leica, ACE200). 3D data were obtained by a scanning electron microscope (Thermo Fisher, Teneo VS) with one ultramicrotome in the specimen chamber, which allowed synchronous sectioning of resin blocks and imaging of the sample surface10. Each serial face was imaged with 2.5 kV acceleration voltage and 0.2 nA current in backscatter mode using a VS DBS detector with a slice thickness of 70 nm. The image store resolution was set to 6144 × 6144 pixels with a dwell time of 2 µs per pixel or 8192 × 8192 pixels with a dwell time of 1 µs per pixel.

3D reconstruction and presentation

The images were aligned, filtered, manually segmented, and used to generate surfaces using the Amira 2021.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) software. The surfaces generated in Amira were exported as MRC files. Chimera was used to reassemble the structures, and the segmentation artifacts were carefully removed. The resulting Chimera projects were used and static images were exported. The volumes and lengths of all reconstructed structures were calculated using the label analysis tool in Amira 2021.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) software.

Cryo-SEM

For the observation of the outer surface of the insect with cryo-SEM, samples were fixed in liquid nitrogen and transferred to a Cryo-SEM system (Leica, EM VCT 500) which preserved samples at −150 °C. They were then plasma coated with 5 nm gold using a cryo-sputter coater (Leica, ACE600) and viewed under a field emission scanning electron microscope (Thermo Fisher, Helios UC G3) at −150 °C.

Analysis of camphor leaves in transcriptional responses to T. camphorae infestation

The non-infested camphor leaves were selected, and infested by T. camphorae (20 psyllids per leaf). Samples were collected 5 days later when the infested area exhibited a slight pit, and approximately 15–20 pit were generated in one leaf (one psyllid usually developed one pit). The whole leaves with no T. camphorae were collected and grinded with liquid nitrogen. The non-infested leaves of the similar developmental stage with the infested one were used as a control. Then, samples were homogenized in the TRIzol Total RNA Isolation Kit (Takara, Dalian, China), and total RNA was extracted following the manufacturer’s protocols. Three biological replicates were performed for each treatment, with each collected on different plants. The RNA samples were sent to Novogene Institute (Novogene, Beijing, China) for transcriptomic sequencing as previously described in ref. 77. Briefly, mRNA isolation from total RNA employed poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. mRNA fragmentation occurred under elevated temperature using divalent cations in NEBNext First Strand Synthesis Reaction Buffer (5X). First strand cDNA synthesis utilized a random hexamer primer and M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase. Subsequently, the second strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H. Blunt ends were generated by converting the remaining overhangs using exonuclease/polymerase activities. Following adenylation of DNA fragment 3’ ends, NEBNext Adaptors with hairpin loop structures were ligated to prepare fragments for hybridization. To select cDNA fragments within the preferred length of 250–300 bp, library fragments were purified using the AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, USA). Subsequently, 3 µl of USER Enzyme (NEB, USA) treated the size-selected, adaptor-ligated cDNA, incubating at 37 °C for 15 min, followed by 5 min at 95 °C, before PCR amplification. PCR employed Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase, Universal PCR primers, and Index Primer. Finally, PCR products were purified using the AMPure XP system, and library quality was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. The index-coded samples were clustered using the acBot Cluster Generation System, with the TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina), following the manufacturer’s guidelines. After cluster generation, library preparations underwent sequencing on an Illumina Novaseq6000 platform. The output raw sequencing reads were filtered to remove adaptor sequences and low-quality reads using Trimmomatic v0.39 (LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:36)78. The clean reads from each cDNA library were aligned to the reference sequences of Cinnamomum camphora79. The low-quality alignments and multiple mappings to the genome were filtered using SAMtools v1.7 with the parameter “-bSF 4”80. Gene expression levels were quantified using Cufflinks, which estimates transcript abundance based on read alignments81. To account for gene length and enable cross-gene comparisons, the expression values were normalized to transcripts per million (TPM) using rnanorm82. This normalization adjusts for gene length and sequencing depth, providing a standardized measure of expression that facilitates biological interpretation. To address differences in sequencing depth and library composition between experimental groups, the TPM-normalized expression matrix underwent further normalization using the TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) method. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using DESeq283, with the false discovery rate (FDR) set at 0.05 and a fold change threshold of ≥2 (log2 fold change ≥ 1 or ≤ −1). In this study, KEGG enrichment analyses were performed using TBtools software v1.069784. In this software, enriched P-values were calculated according to one-sided hypergeometric test: ({P} = 1 – {sum}_{i = 0}^{m-1} left(frac{left({{{bf{M}}}atop{{bf{i}}}}right) left({{{{bf{N-M}}}}atop{{bf{n-i}}}}right)} {left({{{bf{N}}}atop{{bf{n}}}}right)}right)), with N represents the number of gene with KEGG annotation, n represents the number of DEGs in N, M represents the number of genes in each KEGG term, m represents the number of DEGs in each KEGG term.

Statistics and reproducibility

Detailed information of samples used for reconstruction were showed in Supplementary Table 1. All data sets were presented as Mean ± Standard Error of Mean (SEM). Data were analyzed for statistical significance using student’s t-test (Fig. 3B) and using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (Fig. 8B and Supplementary 7B). Statistical significance is indicated with p-values as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.0001. The sample sizes were provided and defined in the corresponding legends. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, www.graphpad.com.

Responses