Three-year analysis of adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with brexucabtagene autoleucel in ZUMA-3

Introduction

Targeted treatments, including blinatumomab and inotuzumab ozogamicin, have improved outcomes for adults with relapsed or refractory (R/R) B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) in recent years, with overall complete remission (CR)/CR with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRi) rates of 44% for blinatumomab and 74% for inotuzumab; however, long-term survival remains low, with a median overall survival (OS) < 8 months following these therapies (median follow-up time: 11.7 and 29.6 months for blinatumomab and inotuzumab, respectively) [1, 2]. Following salvage therapy, patients in remission may receive consolidative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (alloSCT), which has curative potential in some patients with B-ALL [3]. However, alloSCT can result in serious toxicities such as graft-versus-host disease, limiting the number of patients who can tolerate it, and matched stem cell donors can be difficult to locate in a timely fashion [3, 4]. Given the barriers to alloSCT, less than half of patients treated with inotuzumab in the INO-VATE study or blinatumomab in the TOWER study received potentially curative alloSCT [1, 2]. Thus, other salvage therapies with curative potential are needed for patients with R/R B-ALL. More recently, CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies have been approved for R/R B-ALL, including tisagenlecleucel (approved in the United States [US] and European Union for patients aged <26 years) and brexucabtagene autoleucel (brexu-cel; approved in the US for patients aged ≥18 years and in the EU for patients aged ≥26 years), that have improved median OS in this patient population [5, 6]. Another anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy, obecabtagene autoleucel, is currently being investigated in adult patients with R/R B-ALL [7].

In the multicenter, single-arm, Phase 1/2 ZUMA-3 study, patients with R/R B-ALL (N = 78) treated with brexu-cel at the pivotal dose (1 ×106 CAR T cells/kg) had a CR/CRi rate of 73% and a CR rate of 60% [6]. After 2 years of follow-up, the median OS was 25.4 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 16.2–not estimable [NE]) in all treated patients and 47.0 months (95% CI: 23.2–NE) in responders (n = 57) [6]. Outcomes by baseline bone marrow (BM) blast percentage were largely consistent with the overall population, though patients with >75% BM blasts at baseline had numerically lower CR/CRi rates and median OS [6]. Additionally, a post hoc subgroup analysis performed after 2 years of follow-up found that patients in ZUMA-3 benefited from brexu-cel irrespective of prior therapies or subsequent alloSCT status [8]. However, survival appeared numerically higher in patients who received fewer previous lines of therapy and in patients who did not receive blinatumomab or inotuzumab as prior therapies, though unmatched baseline characteristics and small patient numbers may have contributed to these results [8].

Here, we report outcomes after 3 years of follow-up in all treated patients and those aged ≥26 years (the EU patient population) in ZUMA-3, with updated results for subgroups of patients who received blinatumomab, inotuzumab, or alloSCT as prior therapy as well as those responders who received subsequent alloSCT.

Methods

Study design and patients

Full methodology for the ZUMA-3 was previously reported [9]. Briefly, ZUMA-3 was a single-arm, multicenter, Phase 1/2 study (NCT02614066). Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years with R/R B-ALL (>5% blasts in the BM). Prior alloSCT was allowed if conducted ≥100 days before enrollment and immunosuppressive medication was discontinued ≥4 weeks before enrollment. Prior blinatumomab was permitted if patients had documented CD19 tumor expression from BM or circulating blasts following completion of prior line of therapy. If CD19 tumor expression was quantified, then ≥90% CD19-positive blasts were required for inclusion. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each site, all patients provided written informed consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [9].

Procedures

Patients in ZUMA-3 underwent leukapheresis and conditioning chemotherapy (intravenous fludarabine 25 mg/m2 on days −4, −3, and −2; and intravenous cyclophosphamide 900 mg/m2 on day −2), followed by one infusion of brexu-cel at a target dose of 1 × 106 CAR T cells/kg on Day 0 [9]. Subsequent consolidative alloSCT was allowed following brexu-cel, at physician’s discretion but was not protocol-defined [9].

Outcomes

The primary endpoint for ZUMA-3 was overall CR/CRi rate per independent review. Secondary endpoints included overall CR/CRi rate per investigator review, duration of remission (DOR) and relapse-free survival (RFS; patients without CR/CRi by data cutoff were evaluated as having an RFS event at day 0) with patients undergoing subsequent anticancer therapies, including alloSCT, censored (Philadelphia chromosome-positive [Ph+] patients who achieved CR could receive maintenance tyrosine kinase inhibitor [TKI] therapy 2 months after infusion without censoring for subsequent therapy); OS; rate of alloSCT; and safety. Patients began the long-term follow-up period after the month 3 visit and were followed for survival and disease status, if applicable, every 3 months through the month 18 visit and then every 6 months through the month 60 visit. Disease assessment was performed per independent review through the month 24 visit or until disease progression. Disease assessment after the month 24 visit for patients’ whose disease had not progressed was performed per standard of care via investigator assessment. To have all disease assessments up to date in this analysis, remission rates, DOR, and RFS are reported herein by investigator review. An exploratory translational endpoint was CAR T-cell levels in the blood. Additional outcomes reported herein include outcomes of responders who proceeded to subsequent alloSCT, cumulative incidence of progressive-disease (PD) mortality and non-PD mortality, and reasons for non-PD mortality.

Statistical analyses

Updated ZUMA-3 endpoints are reported in Phase 2-treated patients aged ≥18 years and in pooled Phase 1 and 2 patients (including patients aged ≥26 years) treated with the pivotal dose, 1 × 106 CAR T cells/kg. Analyses of OS are also reported in all enrolled patients. Exploratory post hoc subgroup efficacy and safety assessments were performed for patients who did and did not receive prior blinatumomab, inotuzumab, and/or alloSCT [8]. Post hoc subgroup analyses by receipt of subsequent alloSCT were also performed [8]. Subgroup analyses were conducted retrospectively, with inherent differences in sample sizes and baseline characteristics; no hypotheses were tested and only descriptive statistics are reported. Time-to-event endpoints were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

Patients

Manufacturing details in Phase 1 and Phase 2 were previously reported [9, 10]. Notably, the median time from leukapheresis to brexu-cel manufacturing release for Phase 2 US patients was 13 days (interquartile range [IQR], 11–14), and the median time from leukapheresis to brexu-cel delivery to study site for Phase 1 US patients was 15 days (IQR, 14–16) [9, 10]. As of July 23, 2022, the median follow-up time for all treated patients was 41.6 months (range, 32.7–70.3; N = 78), for Phase 1 and 2 patients aged ≥26 years it was 41.6 months (range, 32.7–70.3; N = 63); and for all Phase 2 patients it was 38.8 months (range, 32.7–44.6; N = 55). Baseline characteristics were previously reported and were largely consistent across these three patient populations [8, 9, 11]. Briefly, for all treated patients, the median age was 42.5 years (range, 18–84), the median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1–8), the proportion of patients with >25% BM blasts at baseline was 72%, 22% were Ph+, and the proportion of patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 1 was 72% (Supplementary Table S1) [8]. The median age for Phase 1 and 2 patients aged ≥26 years was 47 years (range, 26–84), the median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1–8), the proportion of patients with >25% BM blasts at baseline was 67%, 25% were Ph+, and the proportion of patients with ECOG PS 1 was 71% [11]. The median age for Phase 2 treated patients was 40 years (range, 19-84; N = 55), the median number of prior therapies was 2 (range, 1–8), the proportion of patients with >25% BM blasts at baseline was 73%, 26% were Ph+, and the proportion of patients with ECOG PS 1 was 71% [9].

As previously reported, most Phase 1 patients (96%) and Phase 2 treated patients (93%) received bridging chemotherapy prior to brexu-cel infusion, with the most common chemotherapy (>20%) being dexamethasone (49%), non-liposomal vincristine (37%), cytarabine (28%), and liposomal vincristine (21%; patients could have received more than one type of bridging chemotherapy) [9, 10]. A total of 38 patients (49%) aged ≥18 years had prior blinatumomab exposure, 17 (22%) had prior inotuzumab exposure, and 29 (37%) had prior alloSCT [8]. Additionally, 15 patients (19%) aged ≥18 years proceeded to subsequent alloSCT while in response following brexu-cel, of which 14 patients had CR/CRi and 1 had partial remission [8].

Baseline patient characteristics for prior treatment subgroups were previously reported in patients aged ≥18 years [8]. Briefly, patients with prior blinatumomab had a median of 3 prior therapies, whereas patients without prior blinatumomab had a median of 2 prior therapies (Supplementary Table S1) [8]. Additionally, patients with prior blinatumomab had a numerically higher BM blast percentage at baseline (70%) versus patients without prior blinatumomab (54%; Supplementary Table S1) [8]. Patients with prior inotuzumab also had a higher median number of prior therapies (3 vs 2) and BM blast percentage at baseline (76% vs 52%) than patients without prior inotuzumab (Supplementary Table S1) [8]. Patients with prior alloSCT had a higher median number of prior therapies versus patients without prior alloSCT (3 vs 2), but both groups had similar baseline BM blast percentages (Supplementary Table S1) [8].

Baseline patient characteristics for responders aged ≥18 years who did or did not proceed to subsequent alloSCT were also previously reported [8]. Responders who proceeded to subsequent alloSCT had fewer median prior therapies (2 vs 3) and lower baseline BM blast percentage than responders who did not (Supplementary Table S2) [8]. Additionally, responders who proceeded to subsequent alloSCT were more likely to be primary refractory (43% vs 28%) and were less likely to have been R/R after prior alloSCT (7% vs 51%; Supplementary Table S2) [8].

Efficacy update

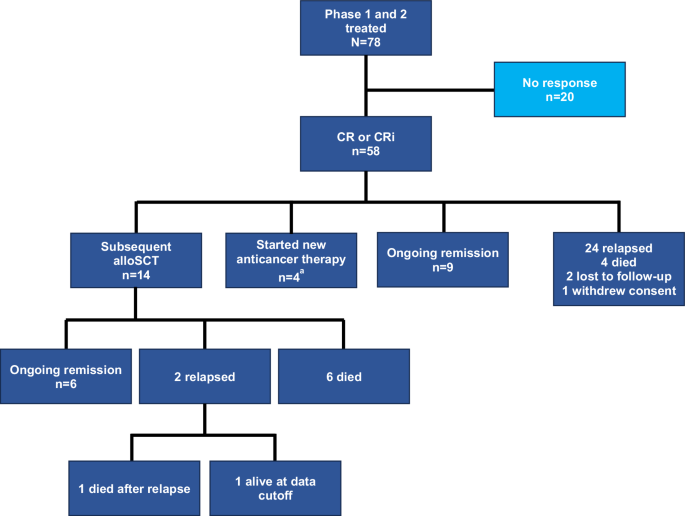

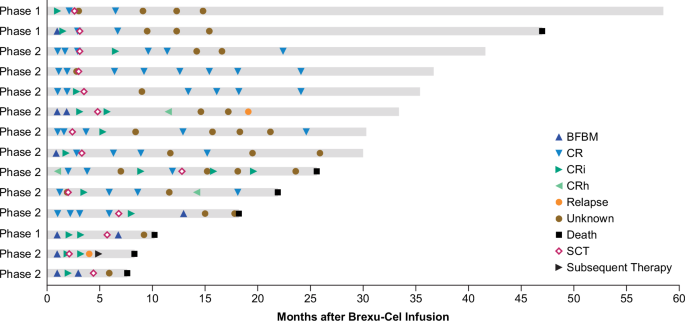

Consistent with the primary analysis, the overall CR/CRi and CR rates per investigator review of all treated patients (N = 78) in this analysis were 74% and 63%, respectively (Table 1) [9]. The median DOR with censoring at subsequent therapy including alloSCT (maintenance TKI therapy was not considered subsequent therapy) was 14.6 months (n = 58; 95% CI, 9.4–23.6; Supplementary Fig. S1A). Of the 58 CR/CRi, 24 relapsed; 14 proceeded to subsequent alloSCT, 9 were in ongoing remission without additional therapy; 4 started new anticancer therapy in remission (reasons for starting subsequent therapy: 2 patients were minimal residual disease (MRD)-positive; 1 patient withdrew partial study consent then relapsed per bone marrow biopsy carried out by investigator prior to starting new anticancer therapy; and 1 started new anticancer therapy prior to formal relapse owing to a measurement of rising MRD by clonoSEQ®); 4 died (n = 1 each of progressive disease, graft versus host disease, COVID-19, and missing cause of death); 2 were lost to follow-up; and 1 had withdrawn consent as of the data cutoff date (Fig. 1). Of the 58 patients with CR/CRi per investigator review, 14 were Ph+ at baseline, of whom, 4 patients (29%) started TKI therapy without being censored as permitted by study protocol. One of these patients subsequently died without relapse; 1 patient subsequently relapsed and died; one patient had subsequent alloSCT shortly after TKI start and was censored at last disease assessment per study protocol, prior to TKI start; and 1 patient remained in ongoing remission without additional therapy as of data cutoff. Among responders aged ≥26 years (n = 47), the median DOR, with censoring at subsequent therapy including alloSCT, was 13.7 months (95% CI: 9.4–24.1; Supplementary Table S3; Supplementary Fig. S1B). The median DOR was 13.7 months (95% CI: 8.7–23.6; Supplementary Fig. S1C) among responders in Phase 2 (n = 40). Similar to previously reported results for Phase 2 patients, the best overall MRD-negative rate at any visit among all treated patients was 79% (95% CI: 69–88; N = 78) and 98% among responders (95% CI: 91–100; n = 58) [9]. In Phase 1 and 2 patients aged ≥26 years, the best overall MRD-negative rate at any visit was 81% (95% CI: 69–90; n = 63) and 100% among responders (95% CI: 92–100; n = 47).

aReasons for starting subsequent therapy: 2 patients were MRD+ and 2 patients were relapsed per bone marrow biopsy carried out by investigator. alloSCT allogeneic stem cell transplant, CR complete remission, CRi complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery.

In all treated patients, the median RFS, with censoring at subsequent therapy including alloSCT, was 11.6 months (N = 78; 95% CI: 6.0–15.5; Supplementary Fig. S2A). In patients aged ≥26 years, the median RFS, with censoring at subsequent therapy including alloSCT, was 11.6 months (n = 63; 95% CI: 3.2–14.8; Supplementary Fig. S2B) and was 11.6 months in Phase 2 patients (n = 55; 95% CI: 2.8–15.5; Supplementary Fig. S2C).

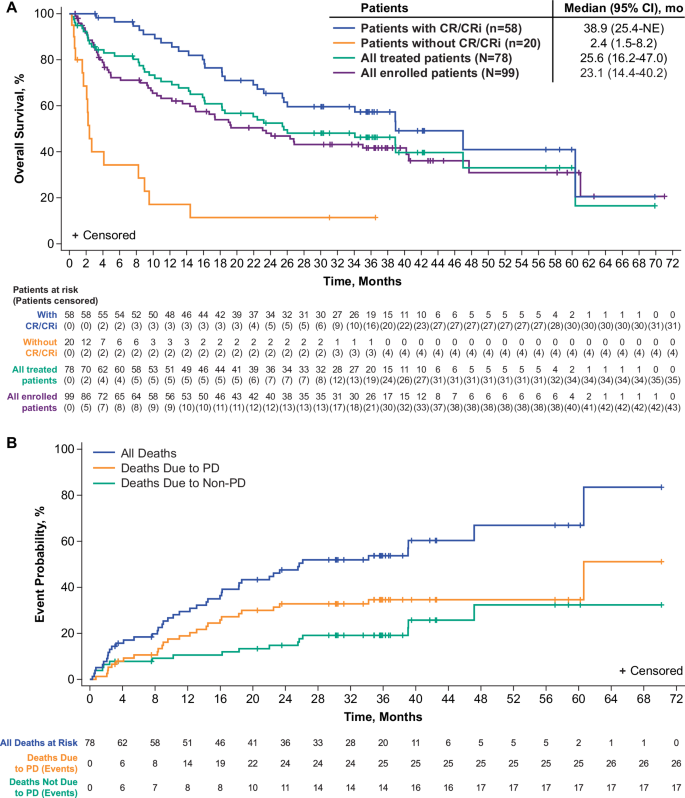

The median OS was 25.6 months (95% CI: 16.2–47.0) for all treated patients (n = 78) and 38.9 months (95% CI: 25.4–NE) for responders per investigator review (n = 58; Fig. 2A), with 28 patients (36%; 26 responders) alive on or after data cutoff. In patients aged ≥26 years, the median OS was 26.0 months (95% CI: 15.9–60.4; Supplementary Fig. S3A) for all treated patients (n = 63) and 47.0 months (95% CI: 25.4–NE) for responders per investigator review (n = 47). In all treated Phase 2 patients (n = 55), the median OS was 26.0 months (95% CI: 16.2–NE; Supplementary Fig. S3C) and 38.9 months (95% CI: 25.4–NE) in responders per investigator review (n = 40). Among all enrolled patients at the pivotal dose, median OS was 23.1 months (95% CI, 14.4–40.2; Fig. 2A) for Phase 1 and 2 patients aged ≥18 years (N = 99); 23.1 months (95% CI, 13.5–47.7; Supplementary Fig. S3B) in patients aged ≥26 years (N = 81); 23.1 months (95% CI, 10.4–40.5; Supplementary Fig. S3D) Phase 2 patients (N = 71).

A Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival, and (B) cumulative incidence function measurements of PD-related mortality, and non-PD mortality. CI confidence interval, CR complete remission, CRi complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery, NE not estimable, PD progressive disease.

Cumulative incidence of cause-specific mortality

The 36-month rate of non-PD mortality for all treated patients was 19% (n = 15) and the 36-month rate of PD mortality was 35% (n = 27; Fig. 2B). At data cutoff, there were 17 patients with non-PD mortality; 1 death was determined to be brexu-cel–related (brain herniation on Day 8), 1 death was determined to be related to both brexu-cel and lymphodepleting chemotherapy (septic shock on Day 18), and 15 deaths were deemed unrelated to brexu-cel. The most common causes of non-PD mortality included graft versus host disease (n = 3; Days 554, 773 and 1429), sepsis (n = 2; Days 50 and 72), and pneumonia (n = 2; Days 15 and 46), with 6 deaths having occurred in patients who received subsequent alloSCT (Supplementary Table S4).

Survival update in key subgroups

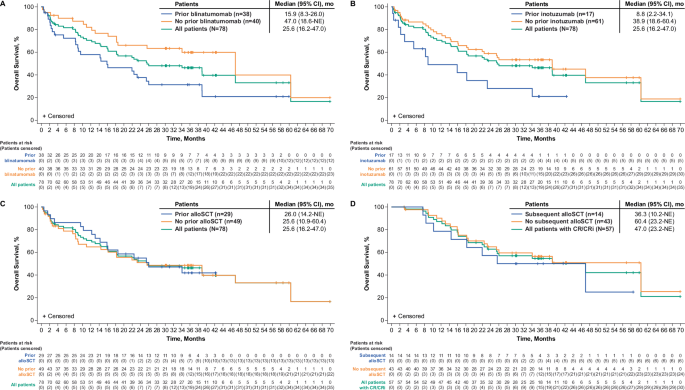

Consistent with previous reports, the median OS for all treated patients with prior blinatumomab exposure (n = 38) was 15.9 months (95% CI: 8.3–26.0), and was 47.0 months (95% CI: 18.6–NE) for patients without prior blinatumomab exposure (n = 40) (Fig. 3A); however, differences in median number of prior therapies and other baseline characteristics may have confounded these results [8]. Trends for median OS also remained consistent with prior reports for all treated patients with prior inotuzumab exposure (n = 17) at 8.8 months (95% CI: 2.2–34.1) and 38.9 months (95% CI: 18.6–60.4) for those without prior inotuzumab exposure (n = 61; Fig. 3B) [8]. With longer follow-up, the median OS estimates for patients with and without prior alloSCT were similar at 26.0 months (n = 29; 95% CI, 14.2–NE) and 25.6 months (n = 49; 95% CI: 10.9–60.4), respectively (Fig. 3C), whereas estimated medians for patients without prior alloSCT appeared higher in a previous report [8].

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival by (A) prior blinatumomab exposure, (B) prior inotuzumab exposure, (C) prior alloSCT exposure, and (D) subsequent alloSCT exposure. alloSCT allogeneic stem cell transplant, CI confidence interval, CR complete remission, CRi complete remission with incomplete hematologic recovery, NE not estimable.

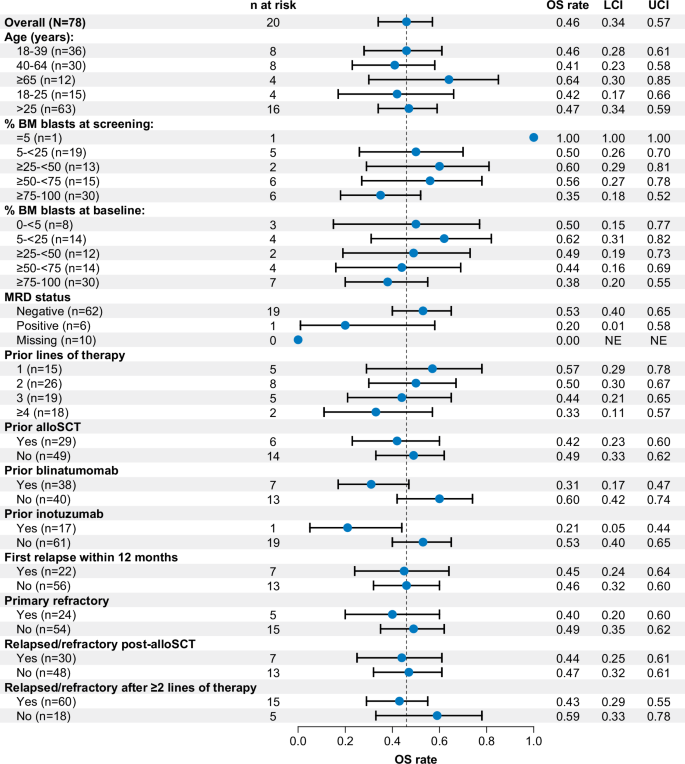

OS rates at 36 months for most key subgroups were largely similar to the overall population (46%; 95% CI: 34–57). Notably, the 36-month OS rates by bone marrow blast percentage at baseline and age categories were similar to that of all patients, but was lower for patients who received blinatumomab (31%; 95% CI, 17–47) or inotuzumab (21%; 95% CI, 5–44) as prior therapy, and was lower among patients who had ≥4 prior therapies (33%; 95% CI, 11–57; Fig. 4). Rates of OS at 36 months among patients aged ≥26 years and Phase 2 patients were similar to those for all treated patients (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5).

Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival at Month 36. alloSCT allogeneic stem cell transplant, BM bone marrow, LCI lower confidence interval, MRD minimal residual disease, NE not evaluable, OS overall survival, UCI upper confidence interval.

Outcomes after subsequent alloSCT

As previously reported, 14 patients with CR/CRi proceeded to subsequent alloSCT while in remission following brexu-cel [8]. Of these patients, 10 had CR as best response and 4 had CRi, with a total median time from brexu-cel infusion of 114 days (range, 78–175) for Phase 1 patients and 101 days (range, 60–390) for Phase 2 patients. As expected and consistent with the 2-year data cut, responders who received subsequent alloSCT (n = 14) and responders who did not receive subsequent alloSCT (n = 43) experienced a numerically longer median OS compared with the overall patient population. However, responders with subsequent alloSCT appeared to experience less benefit with a median OS reached at 36.3 months (95% CI: 10.2–NE; n = 14), whereas responders without subsequent alloSCT had a median OS of 60.4 months (95% CI: 23.2–NE; n = 43 Fig. 3D) [8]. Of the 14 responders who proceeded to subsequent alloSCT, 6 were in ongoing remission at data cutoff, 2 relapsed (1 patient died after relapse), and 6 died without relapse (Fig. 5; n = 1 each of hypoxia on Day 778; hemorrhagic shock due to gastrointestinal bleed on Day 231; herpes simplex viremia on Day 309; multi-organ failure due to infection and graft versus host disease on Day 554; cardiopulmonary arrest on Day 667; and pulmonary graft versus host disease on Day 1429). Median OS results were largely consistent across all subgroups examined among Phase 1 and 2 patients aged ≥26 years and Phase 2 patients (prior blinatumomab: Supplementary Figs. S6A and S7A; prior inotuzumab: Supplementary Figs. S6B and S7B; prior alloSCT: Supplementary Figs. S6C and S7C; subsequent alloSCT: Supplementary Figs. S6D and S7D, respectively).

alloSCT allogeneic stem cell transplant, BFBM blast-free hypoplastic or aplastic bone marrow, brexu-cel brexucabtagene autoleucel, CR complete remission, CRh complete remission with partial hematological recovery, CRi complete remission with incomplete hematological recovery, SCT stem cell transplantation.

Safety update

Safety outcomes for patients in ZUMA-3 after 3 years of follow-up remained largely consistent with previous reports [6]. Brexu-cel–related treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) remained unchanged, and no Grade 5 adverse events occurred since the prior data cut in Phase 1 and 2 patients (N = 78). No new incidence of cytokine release syndrome (CRS), neurologic events, infections, or hypogammaglobulinemia of any grade were reported since the prior data cut. As previously reported, one patient had a secondary malignancy of ongoing Grade 4 myelodysplastic syndrome at data cutoff [9]. Two additional events among 1 patient (Grade 1 and 2 leukemic retinopathy, both resolved with treatment) were previously reported as secondary malignancies but were subsequently recategorized as leukemic retinopathy as a manifestation of the underlying B-ALL (or leukemia) diagnosis [9]. None of these events were T-cell malignancies or deemed related to brexu-cel per investigator assessment [9].

Brexu-cel–related TEAEs, CRS, and neurologic events were largely consistent across prior therapy subgroups. However, patients without prior blinatumomab experienced Grade ≥3 CRS at a numerically lower rate and Grade ≥3 neurologic events at a numerically higher rate than patients with prior blinatumomab. Patients without prior inotuzumab and patients with prior alloSCT experienced Grade ≥3 CRS at lower rates than their respective counterparts (Table 2). Of the 43 patients treated in Phase 1 and 2 who died, 5 deaths occurred since the prior data cutoff due to the following causes, none of which were determined to be brexu-cel–related: progressive disease (n = 2; Day 1036 and Day 1837), hypoxia with acute respiratory distress syndrome and accompanying hypotension (n = 1; Day 778), intracranial hemorrhage deemed related to relapsed ALL with thrombocytopenia and possible central nervous system involvement (n = 1; Day 1183), missing cause of death (n = 1; Day 1184) [12].

Pharmacokinetics update

Consistent with previous ZUMA-3 analyses, median peak and area under the curve from Day 0 to Day 28 (AUC0‑28) anti‑CD19 CAR T‑cell levels were higher in evaluable pooled Phase 1 and 2 patients with ongoing remission (n = 7; median peak, 62.97 cells/μL [range, 21.89–83.99]; median AUC0-28, 698.13 cells/μL×days [range, 185.75–1122.59]) compared with patients who relapsed or died after achieving remission (n = 19; median peak, 23.26 cells/μL [range, 2.18–322.24]; median AUC0-28, 263.13 cells/μL×days [range, 15.29–2624.52]) and non-responders (n = 18; median peak, 2.45 cells/μL [range, 0.00–183.50]; median AUC0-28, 32.08 cells/μL×days [range, 0.00–642.25]; Table 3) [8, 12]. Patients who had alloSCT, started new anticancer therapy, withdrew consent, or were lost to follow-up at data cutoff were not included in this analysis. Similar to results previously reported for Phase 2 patients, of the 9 Phase 1 and 2 patients with ongoing remission, 8 were evaluable for B cell recovery. At 6 months post-infusion, 7 of 8 patients had full B cell recovery, and all 8 evaluable patients had full B cell recovery by Year 1, with no detectable anti-CD19 CAR T cells [12].

Discussion

After 3.5 years of median follow-up in ZUMA-3, patients continued to benefit from brexu-cel therapy, with a median OS of almost 4 years in 58 responders, including 9 patients who were still in ongoing remission without subsequent therapy or alloSCT at data cutoff. Additionally, consistent with prior reports, overall MRD negativity rate was high among responders (98%), which has previously been shown to be associated with longer OS across many studies of adult patients with B-ALL [9, 10, 13]. OS rates at 36 months and median OS across key subgroups were generally similar although patients who received prior blinatumomab or inotuzumab had numerically lower 36-month OS rates and medians relative to the overall population. However, as discussed in a previous analysis, these results may be confounded by differences in baseline characteristics such as number of prior therapies and small sample sizes. For example, patients with prior blinatumomab had a higher disease burden at baseline (70% vs 54% BM blasts) and more prior therapies (median 3 vs 2) versus patients with no prior blinatumomab [8]. Similarly, patients with prior inotuzumab treatment had a higher disease burden and more prior therapies than patients without prior inotuzumab, along with a small sample size of patients treated with prior inotuzumab (n = 17) [8]. Recent reports of patients treated with brexu-cel with and without prior blinatumomab treatment in real-world settings have shown high CR/CRi rates and OS rates at 6 months or 1 year regardless of prior treatment status [14, 15]. Interestingly, in one real-world study, patients who did not respond to prior blinatumomab treatment had a lower 1-year OS rate following brexu-cel therapy versus patients with response to prior blinatumomab treatment or blinatumomab-naive patients [14]. However, we previously reported that responses to brexu-cel in ZUMA-3 were observed regardless of best response to prior blinatumomab therapy. As such, more studies are needed to determine the impact prior blinatumomab and response to prior blinatumomab on efficacy of brexu-cel, but there were patients with prior blinatumomab treatment in both ZUMA-3 and in the real-world analysis who experienced significant benefit from subsequent brexu-cel therapy [16].

Responders (n = 43) who did not proceed to subsequent alloSCT had a numerically higher median OS than responders who proceeded to subsequent alloSCT suggesting that patients who respond to brexu-cel may experience long-term survival regardless of whether they receive consolidation therapy in the form of alloSCT. As previously stated, baseline patient characteristics between subgroups were not balanced, though responders without subsequent alloSCT had a numerically higher median number of prior therapies, numerically higher median BM blasts at baseline, and were numerically more likely to have had prior alloSCT than responders who proceeded to subsequent alloSCT [8]. It is also important to note that 6 of 14 responders (43%) who proceeded to subsequent alloSCT died due to non-PD events, 2 of whom died due to graft versus host disease. Additionally, 35% of all non-PD mortality events (n = 6) occurred in patients who proceeded to subsequent alloSCT. Rates of treatment-related mortality for consolidative alloSCT after CAR T-cell therapy were high (29–35%) in 2 other studies of CAR T-cell therapy in patients with R/R B-ALL, but these also examined small sample sizes (n = 17–21) [17, 18]. Given the small patient numbers in each subgroup and the lack of balanced patient characteristics between responders who did or did not proceed to subsequent alloSCT in ZUMA-3, it is difficult to fully assess the risks and benefits of consolidative alloSCT after brexu-cel treatment. However, given responders without subsequent alloSCT had a median OS of ~5 years, it is clear that long-term remissions can be established without subsequent alloSCT. These results provide support for additional studies with more patients to assess the risks and benefits of consolidative alloSCT following CAR T-cell therapy in R/R ALL.

There were no new safety signals and no new AEs of interest among patients in ZUMA-3 since the prior data cut. This is consistent with the one-time administration of brexu-cel and has been demonstrated in long-term follow-up of other CAR T-cell therapies [5, 19]. Of the 5 deaths that occurred since the previous analysis, none were determined to be related to brexu-cel. Safety outcomes were also largely consistent across patient subgroups, although patients without prior blinatumomab or inotuzumab treatment, as well those with prior alloSCT, experienced fewer Grade ≥3 CRS events. This may be related to the lower disease burden at baseline and smaller number of prior therapies observed in these patient subgroups versus patients with prior blinatumomab or inotuzumab treatment and patients without prior alloSCT [8]. Conversely, patients without prior blinatumomab experienced higher rates of Grade ≥3 NEs for reasons that remain unclear. As noted above, differences in baseline characteristics and number of prior therapies in these subgroups limit interpretation of these results and more studies are needed to fully understand the impact prior therapies may have on adverse events experienced with subsequent brexu-cel therapy.

Given the EU’s approval of brexu-cel is limited to patients aged ≥26 years with R/R B-ALL, we assessed the efficacy and safety outcomes of patients ≥26 years (n = 63) in this follow-up analysis. This patient population benefitted from brexu-cel therapy with outcomes comparable to the overall ZUMA-3 population, suggesting that patients can benefit from brexu-cel treatment regardless of age.

Consistent with previous reports, median peak CAR T-cell levels were higher in ongoing responders versus patients who relapsed or non-responders, suggesting that these parameters may be an early indicator of long-term durability of remissions [6, 8]. As has been suggested previously, the B-cell recovery and lack of detectable CAR T cells in ongoing responders suggest that persistence of CAR T cells in blood is not necessary for maintaining remission after brexu-cel therapy [6]. A prior analysis examined median peak and area under the curve from time of infusion to Day 28 CAR T-cell levels among patients who received prior blinatumomab or inotuzumab treatment versus those who did not. No significant differences in either metric were observed between patients who did or did not receive either of these prior treatments, suggesting that prior targeted therapy did not significantly lessen anti-CD19 T-cell expansion in patients treated with brexu-cel [8].

Limitations of this study include the single-arm study design of ZUMA-3, small patient numbers in certain subgroups, limited availability of independent review of remissions after 24 months, and unmatched baseline characteristics between corresponding subgroups.

With almost 3.5 years of median follow-up in ZUMA-3, updated results demonstrate that brexu-cel continues to provide benefit for adult patients with R/R B-ALL, including responders without subsequent alloSCT. As of the data cutoff date, 9 patients were in ongoing remission per investigator review without subsequent therapies, including alloSCT, suggesting that brexu-cel therapy can produce long-lasting remissions that extend survival in patients with R/R B-ALL. Brexu-cel demonstrated durable efficacy across key subgroups, though survival appeared better in patients not previously treated with the targeted therapies blinatumomab or inotuzumab. However, unmatched baseline characteristics and small patient numbers among subgroups may have contributed to these results. No new safety signals were identified, and no cases of secondary T-cell malignancies have been reported at any time in ZUMA-3. Additional studies are needed to fully assess the impact of prior and subsequent therapies in patients with R/R B-ALL who receive brexu-cel.

Responses