To bond or bridge: how do populist attitudes intensify the effect of online social capital on political engagement?

Introduction

Populism serves as a direct advocate for the interests and concerns of the general population against the perceived dominance of the more powerful elites (Mudde, 2017). Recent studies have seen a (re)surge in discussions on the realization of populism in politics, with notable cases in Europe, America, and Australia examined through a populist lens (e.g., Bourdin and Torre, 2023; Fenton-Smith, 2020; Morieson, 2023). Yet, while populism is often viewed as an indicator of democratic politics, the two are not one and the same, as the latter premises its functioning on institutional mediation, balance of power, and the negotiation among political elites (Arditi, 2003). Populism, on the other hand, does not presuppose democracy but rather its people/elite antagonist relationship, whereby charismatic political leadership establishes itself as “a common man” speaking on behalf of the people, thereby gaining representativeness (and power) by standing with the people and against the elite (Arditi, 2003; Abts and Rummens, 2007). Indeed, democracy is not guaranteed with populism, and there have been undemocratic populists (e.g. Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro) charismatically manipulating the rhetoric for regime stabilization, if not authoritarianism (Spanakos, 2008; Robinson and Milne, 2017; Sagarzazu and Thies, 2019).

Moving from the West to the East, populism emerges as an equally compelling theme. Taiwan, one of the most politically “populist” regions in Asia, has been studied to a great extent, especially since the 2010s with the flourishing of populist political figures (e.g. Krumbein, 2023; Liu, 2022; Wu and Chu, 2019). Examining the role of populism in Taiwan, one observes that populist politicians have appeared across different eras, and more importantly, different parties. From Chen Shui-bian of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in the early 2000s to Han Kuo-yu of the Kuomintang (KMT) in the late 2010s, and more recently, Ko Wen-je of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) founded in 2019, a trend of politicians employing populist strategies involving anti-establishment movements and sentiments is clearly evident (Wu and Chu, 2019). The three aforementioned populist figures, along with many others, distanced themselves from the ruling party, criticized the corruption and ineffectiveness of the existing political system, before discursively and ideologically attacking, if not outright vilifying, their identified “elite” (in the case of Chen Shui-bian targeting the long-ruling KMT, Han Kuo-yu the in-office DPP, and Ko Wen-je the conventional politicians from both DPP and KMT) (Krumbein, 2023; Liu, 2022).

To explore the dynamics of Taiwanese populism, we consider the interrelation of three key factors, namely online social capital, political efficacy, and online political engagement. Among these, political engagement among citizens represents a cornerstone of healthy democratic societies. However, the forms of political engagement have been altered considerably in recent decades due to the rise of digital technologies and online platforms. Social media and other online spaces now serve as important arenas for political discourse, activism, and various forms of digital participation. This shift toward online political engagement has raised questions about its relationship with online social capital (i.e., the resources, networks, and connections that individuals can access and mobilize through internet-based interactions). While past research has explored linkages between offline social capital and conventional political participation, much less is known about how online social capital influences newer modes of digitally-enabled civic and political activities (Ellison et al. 2007; Valenzuela et al. 2009; Boulianne, 2015). On top of that, we also recognize the importance of understanding social capital in its two distinctive forms: bonding and bridging (Putnam, 2000). These are fundamentally different in nature and are likely to contribute to different statistical representations.

Understanding this relationship is particularly important for researchers and policymakers, as younger generations have grown up immersed in digital environments and may engage with politics quite differently than previous cohorts. Factors like political efficacy beliefs and populist sentiments could potentially mediate or moderate how online social capital translates into online political behaviors among young adults. Recent studies have thus begun to address this gap. Gil de Zúñiga et al. (2012), for instance, found that online social capital significantly predicts online political participation, indicating that digital interactions can in fact foster political engagement. Similarly, Skoric et al. (2016) demonstrated that social media use enhances political participation by facilitating exposure to diverse viewpoints and fostering civic discussion. In terms of the role of social media in mobilizing young citizens and enhancing their political efficacy, Theocharis and Quintelier (2016) have observed its significance.

In light of these developments, our study aims to further explore the nuanced relationship between online social capital and political engagement in the digital age, in which populism may play a significant role in catalyzing online interactions into more active forms of political participation. The fact that Taiwanese politicians approach their supporters regularly through official websites and social media, keeping them abreast of recent policies, international relations, and cross-party dynamics, promotes populism in an online context, thereby influencing individual behaviors and aligning them more closely with political processes. The realization of online political engagement can be seen in occasions where individuals express their thoughts, preferences, and criticisms of political parties or political figures on social media. This activeness, as we argue, is likely to be enhanced by members of their online networks, such as close friends or family members, with similar stances (bonding social capital), and connections with those holding differing perspectives through broader online platforms (bridging social capital). This process will likely be further facilitated assuming individuals have the willingness — which can be fostered through education, mass communication, societal norms, and more — to engage themselves in politics (political efficacy).

Therefore, we hypothesize that populism, through the cultivation of political efficacy as a mediator, can intensify the impact of online social capital on political engagement. To test our hypotheses, we conducted an empirical study focusing on young adults, a demographic particularly active on social media and whose political attitudes and behaviors are still in formation. By examining how online social capital and populism interact to influence political engagement within this group, we aim to add resolution to the understanding of the evolving landscape of political participation in the digital era.

Our study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, it adds to the current understanding of how online social capital relates to political engagement, a relationship still not fully understood despite its growing significance. Second, it highlights the role of populism as a moderating factor, offering a new perspective on how political ideologies can shape the impact of social media on political behavior. Finally, by focusing on young adults in Taiwan, this study provides insight into the digital political behavior of a demographic often at the forefront of technological adoption and political activism. Taiwan, a new democracy in Asia where electoral populism is taking its own course, provides a unique context for examining the role of online social capital (OSC) in political engagement. The country’s high internet penetration and vibrant democratic culture make it an ideal setting for studying how digital interactions influence political behaviors. Since the 2010s, Taiwan has seen the flourishing of populist political figures, which has further intensified the political discourse on digital platforms. Our study situates these dynamics within the broader landscape of Taiwanese political engagement, exploring how OSC, facilitated by digital platforms, is mobilized in this populist climate. This context is integral to understanding the practical implications of our findings, particularly in how different forms of OSC (bonding vs. bridging) interact with political efficacy to shape online political engagement among young adults.

In the following sections, we review the relevant literature on online social capital, political engagement, political efficacy, and populism, and outline our research methodology. We then present our empirical findings, discuss their implications, and conclude with suggestions for future research in this area.

Literature review

Bringing things online: online social capital and online political engagement

The interrelation between social capital and political engagement, which has been an often deliberated topic in political studies, serves as the focus of our initial examination. Traditionally, social capital has been defined as an effort to enhance the social coherence and efficiency of society by way of social organization, including trusts, norms, and networks (Putnam, 1993). Political engagement, on the other hand, is characterized as “individual acts intended to influence the political system in some ways” (Milbrath, 1965, p. 18). Verba et al.’s (1995) civic voluntarism model predicts political engagement with socioeconomic status (SES) as an embodiment of resources (along with psychological engagement, recruitment, and issue engagement). The interrelation of social capital offline and traditional forms of political engagement has been studied in multiple contexts, sometimes with the usage of mass media (e.g. Dodd et al. 2015; Hyman, 2002; Zhang and Chia, 2006). A general positive correlation in general has been confirmed by previous studies: a higher level of social capital, embodied in mutual trust and connection towards society, often yields improved civic and political participation (e.g. Gibson, 2001; Kapucu, 2011; Mishler and Rose, 2005).

With the Internet and various forms of digital technologies evolving rapidly over the past decades, studies have tended to bifurcate social capital into “offline” and “online” discussions, especially when focusing on resources obtained through people that can only be connected online instead of offline (e.g. Constant et al. 1996; Williams, 2006; Wohn et al. 2013). By bringing social capital “online”, Faucher (2018) argues that it becomes a product of online exchanges that can be “built through strategies of accumulation” (p. xvi). As the online environment facilitates the accumulation of social capital in a wider range of audiences, users often convert their experiences and labor (both cognitive and creative) from an offline to online setting, generating online social capital (Faucher, 2018). Some propose a further delineation of Putnam’s (2000) “bridging” and “bonding” social capital, whereby the former is obtained from weak, tentative, and sometimes wide relationships lacking the depth that may broaden horizons or inform new world views, while the latter refers to strongly bonded personal connections (e.g. families, close friends) that provide emotional and substantial support, as well as mobilized resources. Williams (2006), for example, examines the concept of online social capital in the context of Granovetter’s (1973) weak-tie hypothesis, interrelating weak-tie networks to online bridging social capital and their strong-tie counterparts to online bonding social capital, thus offering a new perspective for various similar studies (e.g. Ahmad et al. 2022; Kwon et al. 2013; Sajuria et al. 2014). Thereafter, the study of Gibson and McAllister (2013) identifies bonding as the only kind of social capital positively significant for political participation. Sajuria et al. (2014) reach a similar conclusion, but indicate that online bridging social capital can be observed with the presence of nongovernmental organizations or professional brokers.

Along with social capital, the concept of political engagement has progressed over time in terms of both definition and form. Since the arrival of the digital era, political engagement has shifted in terms of its nature, and scholars have thus started assessing political engagement online versus offline (Bimber and Copeland, 2013). Individuals and groups involved in civil or political society are engaged online through the Internet, digital media, and technology, resulting in empowerment through civic culture and deeper participation (Dahlgren, 2000; Tiemann-Kollipost, 2020). Newer forms of online political engagement with social media including Facebook, Instagram, and X (formerly Twitter) have thus been studied (e.g. Blank and Lutz, 2017; Geise et al. 2020; Halpern et al. 2017), as major political events have materialized in the forms of online crowdfunding, agenda communication and various forms community participation in the U.S. election 2020 (e.g. Ahmed et al. 2023; Baber et al. 2022; Green et al. 2022); or “GetUp!”, an online, independent, progressive political group in Australia (e.g. Vromen, 2015, 2017; Vromen and Coleman, 2013).

As previously discussed, the significance of studies on social capital and political engagement in their conventional forms is well established, with the latter being cultivated by the former. Meanwhile, digital technology is significantly impactful in offering “entirely new forms of political participation” (Theocharis et al. 2023, pp. 802–803). Taking these into account, we hypothesize that a similar interrelation exists when both variables are present in an online context.

In this regard, efforts have been made to study the interrelation between online social capital (or social media social capital) and political engagement. Lee (2022) reveals that “Twitter social capital” is strongly associated with traditional participation in political organizations; likewise, Bush (2018) confirms that social media usage for gathering information enhances the level of online social capital, which further drives individuals to be more civically and politically active.

Discussion of both social capital and political engagement in their online forms, however, has been somewhat limited. The two often presented in the form of comparative studies between offline and online forms, instead of directly inspected for their causal relations (e.g. Gil de Zúñiga et al. 2017; Sajuria et al. 2014; Skoric et al. 2009). Yet, as noted by Park and You (2021, p. 1758), the associations between social capital and political engagement should indeed be contextualized online, as “the decline in participation in offline communities is not sufficient to predict the decline of social capital or democracy, because online communities can be expected to serve as social capital”. This study, therefore, aims to shed light on the dynamics at play within the association of online social capital and online political engagement.

Efficacy matters: political efficacy as a mediator

When political matters are negotiated, especially when individuals are studied as research subjects, behavioral explanations can be obtained by considering their political (self-)efficacy (Aberbach, 1969; Miller and Miller, 1975; Pollock, 1983). Political efficacy describes one’s willingness to engage in political processes as a result of his or her perception of the potential for political or social change (Campbell et al. 1954; Caprara et al. 2009). It has been one of the key factors in explaining one’s intention for, or level of, political engagement (e.g. Rosenstone and Hansen, 1993; McCluskey et al. 2004; Verba et al. 1995), as it positively influences active participation in socio-political and democratic engagement, typically by reinforcing belief in one’s power to influence government actions, policies, or even systems (Finkel, 1987; Gil de Zúñiga et al. 2017). Moreover, it should be noted that oftentimes when it is associated with political engagement, internal rather than external efficacy tends to have a stronger effect on prediction (e.g. Krampen, 2000; Marx and Nguyen, 2016; Reichert, 2016).

In an online context, political efficacy has exhibited a strong tendency to affect political engagement. While survey data might be limited, cross-sectional, single-country studies have revealed a clear and stable association between political efficacy and online engagement in various national contexts (Oser et al. 2022). It is thus unsurprising that political efficacy with online political engagement has become a new, but validated trend in the investigation of political participation of young adults, with corresponding case studies conducted in mainland China (e.g. Tang and Wen, 2023; Wei and Zhao, 2017; Ye and Zhang, 2017) and South Korea (e.g. Lee, 2021; Park, 2015; Park and Karan, 2014).

This focus on political efficacy naturally extends to its antecedents, particularly social capital, which has long been recognized as a key factor shaping individuals’ sense of efficacy. Indeed, empirical research has verified the positive association between social capital and political efficacy, by which more capital yields higher efficacy (e.g. Bäck and Kestilä, 2009; Schyns and Koop, 2010). Individuals with higher levels of social capital tend to be more interested in politics and tempted to participate in civil society, as those “with strong ties to the community tend to have a greater degree of access to and confidence in community resources” (Chung et al. 2022, p. 612; Schyns and Koop, 2010). Yet, despite the fact that researchers may be expected to examine online social capital in light of the younger generation more frequently using online media (e.g. Park and You, 2021), there has been a paucity of research examining its association with political efficacy within an online context.

As one of the most “immediate attitudinal” explanations of political actions (Wolfsfeld, 1986, p. 108), the mediating effect of political efficacy on interrelations pertaining to social capital has been identified by empirical studies (e.g. Liu et al. 2023; Park and Shin, 2005). This research, therefore, takes into account and anticipates the inevitably significant online context, with political efficacy as a mediating factor between individuals’ online (bonding and bridging) social capital and levels of online political engagement.

Populism as a moderator: politicizing “the people” online?

Populism is frequently framed as a dichotomy of “the people” versus “the elite” (Hwang and Park, 2023; Venizelos, 2023), with Mudde (2004) further refining this division to distinguish between “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite”. In theory, “the people” possess a general will and are homogeneous (Mudde, 2017), whereas “the elite”, on the other hand, are believed to enjoy privileges that disregard the common good and risk alienation from the ordinary people (Abts and Rummens, 2007; Schedler, 1996). As a result, they are often accused of corruption and portrayed as immoral for marginalizing the interests of the general populace (Demertzis, 2006; Mudde, 2017). In other words, to further reinforce the effect of the dichotomy, moral terms are employed: the elite are vilified, while the people are glorified (Bonikowski, 2016).

Efforts have been made by scholars to analyze the interrelation between social capital and populism. The 2016 U.S. elections which saw Donald Trump, the former president elected, have emerged as a particularly emblematic focus of studies of populism in contemporary American politics, as researchers argue thatsupport for populist candidates represents the result of the declining social capital of U.S. citizens (e.g. Giuliano and Wacziarg, 2020; Lynch et al. 2022; Rodríguez-Pose et al. 2021). Algan et al.’s study (2019, as cited in Boeri et al. 2021) on the role of social capital in the context of the 2017 French presidential elections shows a similar trend, as voters with low interpersonal trust were found more likely to vote for Marine Le Pen, a widely-regarded populist candidate.

Following Putnam’s concept, in parallel with the impact on social capital, political negotiations are also likely to be affected. Ideally, “the people” in the populist notion should not only be the source of political power in a democratic society, but also rulers of a nation who may criticize and rebel against the political regime (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser, 2017). Various studies have been conducted to analyze political engagement within populist ideological settings, classifying these as country-based or continental (often Pan-European) case studies, and examining participation in various forms, such as petition signing and voting (Anduiza et al. 2019; Huber and Ruth, 2017; Rhodes-Purdy, 2015). Efforts to shed light on the correlation between political efficacy and populism have also been made (e.g. Geurkink et al. 2020; Rico et al. 2020; Magni, 2017). The study of Geurkink et al. (2020) serves as one such account of contemporary populism which reveals that political trust and external political efficacy do indeed affect populist attitudes, further relating to different populist voting preferences.

Our study explores populism as a moderating factor in terms of “populist attitudes”. We adopted the individual-level measure by Van Hauwaert et al. (2020), conceptualized based on “anti-elitism, the sovereignty of the people, and a Manichean division of the world into good and bad” (p. 3). In examining the relationship between political efficacy (our mediator) and populist attitudes (our moderator), both have been shown to drive anti-elitism among “the people” (Geurkink et al. 2020). The absence of both factors can lead to limited or even unexpected effects on electoral participation (Jacobs et al. 2024).

Therefore, despite the idea of populist attitudes originally being distinctively associated with explaining voting behaviors (e.g. Akkerman et al. 2014; Van Hauwaert and van Kessel, 2018), we suggest in this study that they take up the role of mobilizing “the people” in general to involve in political engagement. While past studies focus on populism with conventional participation, we specifically address the under-analyzed online context, for which Engesser et al. (2017) identify five populist elements, namely emphasizing the sovereignty of the people, advocating for the people, attacking the elite, ostracizing others, and invoking the ‘heartland’. Specifically, we hypothesize that with populist attitudes serving as a moderator, online social capital is positively associated with online political engagement, mediated by political efficacy.

As such, our study seeks to fill the gap in understanding the impact of populism on social capital, political engagement, and political efficacy, with populism deliberately identified and hypothesized as the moderating factor. Moreover, in accordance with Verba et al.’s (1995) civic voluntarism model, SES here is also tested as a co-moderator with populism. The highlighting research question delves into how populism intensifies or weakens the effect induced by online social capital through political efficacy, ultimately impacting the online political engagement of young adults.

The case of Taiwan in a populist lens

Taiwan had been under authoritarian rule with strict political control characterized as the White Terror Era, whereby the Kuomintang (KMT) had been the only legitimized party in the hands of Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo (Chen, 2008). Following the lifting of the suppressive “Martial Law” and the “Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion” in 1987 and 1991 respectively, Taiwan transitioned to participatory politics with the realization of electoral democracy in 1992 (Hsu, 2009; Tsai and Tsai, 2024).

Populism then came into play right after the start of parliamentary politics. When Lee Teng-hui of KMT was elected president in the 1990s, scholars argued that his governance exemplified “authoritarian populism”. His promotion of Taiwanese patriotism, alongside KMT’s long-standing dominance, raised concerns that the democratization process might paradoxically serve as a means for the party to maintain control and establish a legitimized authoritarian state (Hsu, 2011; Krumbein, 2023; Wang and Chang, 2023).

Parties other than the KMT emerged following Taiwan’s democratization, and DPP led by Chen Shui-bian took office in the general election 2000 (Hsu, 2009; Shyu, 2008). Since then, Taiwan’s political landscape has been shaped by the party rivalry between KMT and DPP (e.g. Fell, 2005; Rigger, 2014), and until fairly recently, the inclusion of TPP (e.g. Hioe, 2024; Nachman, 2024). Populism during this period is characterized as “electoral populism”, as the election-driven democratization often sees populist rhetoric to mobilize “the people”, influence policy-making, and manipulate election outcomes (Shyu, 2008; Wang and Chang, 2023). In the general election 2020, for instance, Han Kuo-Yu of the KMT established himself as a “common man”, aligning himself with the interests of the low-skilled and economically unprivileged, and gaining support through the catalyst of perceived economic insecurity (Krumbein, 2023; Tsai and Pan, 2021). Wielding his anti-elite discourse against the ruling DPP, he voiced an ambition to overturn the “economically and morally decaying” Taiwan (Batto, 2021; Krumbein, 2023). TPP’s Ko Wen-je adopted a similar anti-establishment rhetoric, but with a different target of the “corrupt elite”. Framing the general public as diligent individuals who have fallen victim to a government controlled by special interests and political elites from outside their ranks, he resonated with populist sentiments. As a result, TTP has been presented as an alternative choice for the people to replace the mainstream political parties in the general election 2024 (Shen, 2024).

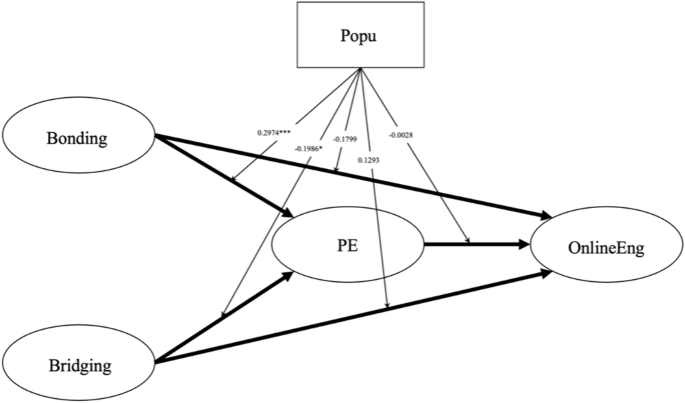

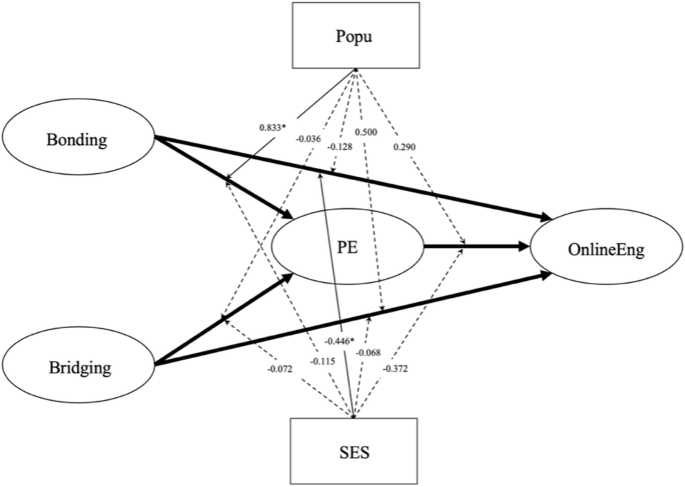

This backdrop of populist politics in Taiwan provides a distinctive context for our study. In particular, our focus is on the manifestation of populist attitudes, which we define as individuals’ agreement with populist features (e.g. anti-elitism sentiments, a people/elite antagonistic relationship, etc.). While we acknowledge the influence of populist leaderships with which these attitudes are affiliated, our primary concern is not individuals’ specific preferences for any political parties or politicians, but rather how they perceive and respond to populist themes in Taiwan’s electoral politics. This distinction is integral to the analysis and interpretation of our findings, as we see that populist attitudes exert a moderating effect on our theoretical framework (see Fig. 3 for such illustration and result).

Research hypotheses

Based on the above literary framework, we develop the following research hypotheses to examine the role online bonding social capital and online bridging social capital play in catalyzing online political engagement, as well as the significance of political efficacy in mediating those associations. We also test for moderating effects of populism and SES in the following:

-

1.

Direct Association Hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Higher levels of online bonding social capital are associated with higher levels of political efficacy.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Higher levels of online bonding social capital are associated with higher levels of online political engagement.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Higher levels of online bridging social capital are associated with higher levels of political efficacy.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Higher levels of online bridging social capital are associated with higher levels of online political engagement.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Higher levels of political efficacy are associated with higher levels of online political engagement.

-

2.

Mediating Effect Hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Political efficacy would mediate the association between online bonding social capital and online political engagement.

Hypothesis 7 (H7): Political efficacy would mediate the association between online bridging social capital and online political engagement.

-

3.

Moderating Effect Hypotheses:

Hypothesis 8 (H8): Populism would moderate the association between online bonding social capital and political efficacy.

Hypothesis 9 (H9): Populism would moderate the association between online bonding social capital and online political engagement.

Hypothesis 10 (H10): Populism would moderate the association between online bridging social capital and political efficacy.

Hypothesis 11 (H11): Populism would moderate the association between online bridging social capital and online political engagement.

Hypothesis 12 (H12): Populism would moderate the association between political efficacy and online political engagement.

-

4.

Co-moderating Effect Hypotheses:

Hypothesis 13 (H13): Populism and socioeconomic status would co-moderate the association between online bonding social capital and political efficacy.

Hypothesis 14 (H14): Populism and socioeconomic status would co-moderate the association between online bonding social capital and online political engagement.

Hypothesis 15 (H15): Populism and socioeconomic status would co-moderate the association between online bridging social capital and political efficacy.

Hypothesis 16 (H16): Populism and socioeconomic status would co-moderate the association between online bridging social capital and online political engagement.

Hypothesis 17 (H17): Populism and socioeconomic status would co-moderate the association between political efficacy and online political engagement.

Participants and procedure

In 2022, we conducted a self-administered online survey targeting students enrolled in higher education institutions (HEIs) across Taiwan. The selection of HEI students as our sample is not only based on their higher propensity to be active online, but also their critical role in Taiwan’s future social and political landscape. Young adults, especially those in higher education, are not only highly active online but are also at a formative stage in developing their political opinions and behaviors. Moreover, over 90% of Taiwanese young adults aged 20–29 are active on social media platforms, making them an ideal group for studying online social capital and political engagement (Taiwan Internet Information Centres, 2020). Moreover, university students in Taiwan are in an educational environment that encourages critical thinking and political awareness, likely enhancing their political efficacy and participation. While this setting may differentiate them from other young adults who are not enrolled in higher education—and who may exhibit different political engagement patterns—it also positions them as a particularly influential group in shaping future political landscapes.

Compared to the general population, this group of respondents may enjoy a slightly higher socioeconomic status, as it includes individuals who are more likely to pursue higher education. In terms of SES, our sample includes a mix of students from different economic backgrounds that we have categorized based on their parents’ occupations, which may still differ from the SES distribution of all 20–29-year-olds in Taiwan. Considering the high enrollment rates of 86% in Taiwanese higher education, such a sample of university students can still offer us a rough picture of internet behaviors among Taiwanese young people.

To this end, we selected a random sample of 12 universities from three regions (Northern, Middle, and Southern regions) and distributed online questionnaires to each institution. Our sample includes participants from the Northern, Middle, and Southern regions of Taiwan, which are known to differ in terms of population density and socioeconomic status (SES). The Northern region, being more densely populated and economically developed, may have a higher average SES compared to the Middle and Southern regions. The dataset was compiled from the participating universities, consisting of 8 public HEIs and 4 private HEIs. From the distributed questionnaires, we received responses from 720 individuals, achieving a response rate of approximately 62.5%. To ensure data integrity and exclude careless responses, we applied two screening criteria and only included participants who took at least 10 minutes to complete the survey. This resulted in a final sample of 450 respondents (52.22% female; age range = 20–29 years).

Measures

Online social capital

Williams (2006) developed a scale for social capital with offline and online variants, integrating subscales of bridging capital and bonding capital with 10 items each, and using 5-point Likert scale response sets. We adopted the wording from the original “online social capital” measure, and the items were translated into traditional Chinese and inspected by bilinguals. The concepts used for developing the bridging items included (1) outward looking, (2) contact with a broader range of people, (3) a view of oneself as part of a broader group, and (4) diffuse reciprocity with a broader community. An example item is “Interacting with people online/offline makes me want to try new things.”. The concepts used for developing the bonding items were (1) emotional support, (2) access to scarce or limited resources, (3) ability to mobilize solidarity, and (4) out-group antagonism. One example item is “There is someone online/offline I can turn to for advice about making very important decisions.” The Cronbach’s Alpha for Online Bridging Capital was 0.929; The Cronbach’s Alpha for Online Bonding Capital was 0.789.

Political efficacy

The Perceived Political Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (PPSE-S) created by Vecchione et al. (2014) was aimed at measuring the political efficacy of research respondents. The four items of the scale were translated and back-translated between traditional Chinese and English before a finalized traditional Chinese version was approved by two linguistic raters. Respondents were asked to indicate how capable they felt in carrying out the specific action or behavior described (e.g. “Promote public initiatives to support political programs that you believe are just”) according to a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely). The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.783.

Populism

Van Hauwaert et al. (2020) arranged a measure of eight items (Likert scale 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) to evaluate populist attitudes, six of which correspond with those put forth by Akkerman et al. (2014). The eight-item scale was developed as an extension of the original six-item scale due to the perceived inability of the six-item scale to capture medium-to-high levels of populist attitudes. One illustration of the items is “Politicians always end up agreeing when it comes to protecting their privileges.”. We conducted bidirectional translation between English and traditional Chinese on the eight items, and the results were reviewed by the author and co-authors. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.790.

Online political engagement

Nine items were used to measure respondents’ online political engagement (Vissers and Stolle, 2014). Four items are focused on political engagement through Facebook, such as “Joined FB group started by friends or private citizens to support social/political goal”; the remaining five items are based on other forms of online political participation, such as “Taken part in a march or demonstrated”. A modified scale of eight items was applied in this study. All items were translated and back-translated with the assistance of Chinese-English bilinguals, and discrepancies were identified and discussed before finalizing the traditional Chinese version scale. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they agree (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) that they will or would be willing to engage in each of the political activities. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.917.

Results

Descriptive profile

Table 1 displays the descriptive profile for the research participants (total N = 450, Male=215, Female=235). Participants with valid answers all fell in the 20–29 age range. In terms of household monthly income, we observe that there were 7 males (1.56%) and 10 females (2.22%) with no household income; and 32 males (7.11%) and 36 females (8.00%) had unknown as an answer or did not respond. The majority of males fell in the 70,001–100,000 NTD and 100,000–200,000 NTD income range (both 8.67%), while the majority of female participants fell in the 70,001–100,000 NTD income range (10.22%). Furthermore, the majority of participants reside in the northern area of Taiwan.

Perceived social class status for males and females include, 28.89% and 30.22% who were identified as middle class, 13.56% and 14.44% as lower middle class, 3.33% and 4.22% upper middle class, 2.00% and 3.11% lower class, and 0.0% and 0.22% as upper class respectively. We also added “father’s occupation” and “mother’s occupation” in the questionnaire, and in Table 1 we chose the higher of the two to represent family’s socioeconomic status. Compared with perceived social status, we observe relatively large differences in middle class (59.11% perceived, 20% when measured by parents’ profession) and upper class (0.22% perceived, 20.67% when measured by parents’ profession).

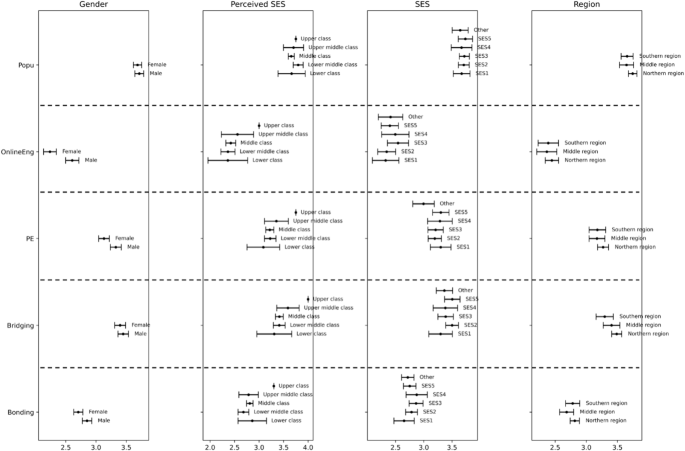

For a preliminary overview of respondents’ behavior, we provide cross-sectional descriptive statistics (Table 2). First, we observe males averaging higher than females on all the items of interest (online bonding social capital, online bridging social capital, political efficacy, online political engagement, and populism). In terms of perceived social class status, we first exclude upper class from this discussion, since there is only one respondent, leading to questionable representativeness. The average responses in perceived social class status lack observable patterns, but we do observe that the upper middle class averaged the highest in online bridging social capital, political efficacy, and online political engagement. The lower class averaged the highest on online bonding social capital, and the lower middle class averaged the highest on populism. For the socioeconomic status (SES) measured by parents’ occupation, we observe no meaningful pattern. However, we note the highest average responses approximating each other (<0.01) in different SES groups, e.g., online bonding social capital (SES3 = 2.86, SES4 = 2.87), online bridging social capital (SES2, SES5 = 3.50), and political efficacy (SES4 = 3.29; SES1, SES5 = 3.30). Based on an overall observation of the behavior in different regions in Taiwan (northern, middle, and southern), we spot a salient trend by which respondents from the northern region average the highest on every measure. Additionally, the statistics reveal subtle differences regarding the average degree of political efficacy, online political engagement, and populism among respondents from the middle and southern regions. These regional differences are significant and should be considered when interpreting our findings, as they may impact the generalizability of our results. We have thus taken these regional variations into account in our analysis, particularly regarding their influence on online social capital and political engagement (See Fig. 1).

Popu populism, Bonding online bonding social capital, Bridging online bridging social capital, OnlineEng online political engagement, PE political efficacy. SES levels are displayed as SES1-5. 2. Upper class in perceived SES only had one respondent, hence represented by the respondent’s original data.

Correlation Analysis

In Table 3 we display the correlation matrix of our variables of interest. The abbreviations include Popu = populism, Bonding = online bonding social capital, Bridging = online bridging social capital, OnlineEng = online political engagement, and PE = political efficacy. The independent variables (IV) online bonding social capital (({r}_{{PE}}) = 0.428, ({r}_{{OnlineEng}}) = 0.561, all p < 0.001) and online bridging social capital (({r}_{{PE}}) = 0.400, ({r}_{{OnlineEng}}) = 0.390, all p < 0.001) are significantly and positively correlated with the mediator political efficacy and the dependent variable (DV) online political engagement. The IVs themselves are also positively correlated ((r=) 0.464, p < 0.001). However, the moderator populism is only correlated with online bridging social capital and political efficacy (({r}_{{Bridging}}) = 0.232, ({r}_{{PE}}) = 0.179, both p < 0.001). Additionally, the IV online political engagement and the mediator political efficacy are positively correlated ((r=) 0.471, p < 0.001).

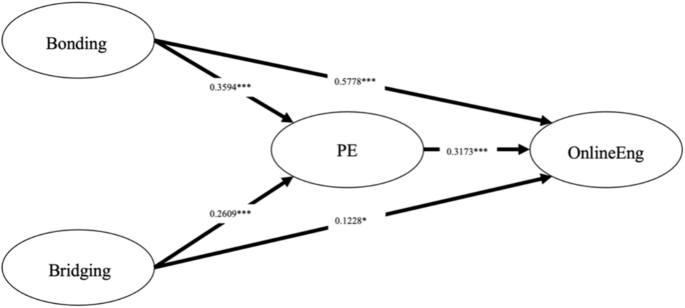

Mediation analysis

Before conducting the moderated mediation analysis, we test for simple mediation (see Fig. 2 for conceptual diagram; see parameter estimates in Table 4). We can observe that the IVs online bonding social capital and online bridging social capital are positively affecting the DV online political engagement (({a}_{1}) = 0.5778, CI[0.4555, 0.7000]; ({a}_{2}) = 0.1228, CI[0.0178, 0.2280]). Furthermore, online bonding social capital and online bridging social capital both positively influence political efficacy, while political efficacy positively impacts online political engagement (({b}_{1}) = 0.3594, CI[0.2530, 0.4660]; ({b}_{2}) = 0.3173, CI[0.2159, 0.4190]; ({b}_{3}) = 0.2609, CI[0.1684, 0.3540]). Finally, from the significant indirect effects, ({c}_{1}) = 0.1140 (CI[0.0644, 0.1640]), and ({c}_{2}) = 0.0828 (CI[0.0433, 0.1220]), we can determine that a mediation effect exists, and thus we proceed to conduct the moderated mediation analysis.

Bonding online bonding social capital, Bridging online bridging social capital, OnlineEng online political engagement, and PE political efficacy. 2. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Moderated mediation analysis

For a conceptual diagram, see Fig. 3. In Table 5 we report the parameter estimates of the interaction terms. In Table 6 we then illustrate the conditional mediation with different moderator levels (i.e., the mean-1SD, the mean, the mean+1 SD). Of the five paths tested for moderation, the paths online bonding social capital to political efficacy and online bridging social capital to political efficacy are significantly moderated by populism, with estimated interaction effect coefficients of 0.2974 (CI[0.1215, 0.4733]), and −0.1986 (CI[−0.3542, −0.0429]) respectively. This indicates that as the effects of online bonding social capital and online bridging social capital on online political engagement are mediated by political efficacy, the interference of the moderator, populism, will cause the effect of online bonding social capital on political efficacy to increase, and the effect of online bridging social capital to decrease. This statement can be corroborated in the table of conditional mediation (Table 6), where we see that the effect of online bonding social capital on political efficacy is increasing (0.1752, 0.3355, 0.4958, all significant) as the moderator level increases, whereas the effect of online bridging social capital on political efficacy is decreasing (0.3410, 0.2339, 0.1269, all significant). Likewise, the indirect effects behave in a similar way, with the indirect effect of online bridging social capital even falling out of the significance interval as the moderator reaches the highest level (mean+1 SD) in Table 6. In summary, apart from the significant interaction terms, we can observe mostly significant and dissimilar indirect effects, indicating the presence of different levels of indirect effects as the value of the moderator changes. Consequently, we determine that there is a moderated mediation effect within our model.

Popu populism, Bonding online bonding social capital, Bridging online bridging social capital, OnlineEng online political engagement, and PE political efficacy. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

Co-moderation on Individual Paths

In the previous section we discussed the moderated mediation effect with populism as the moderator for each path. To further examine the moderating effects of populism accompanied with socioeconomic status, we conduct co-moderations on each path. It also should be noted here that we excluded the data of 45 participants classified as “other” in socioeconomic status (refer to Table 1). This is due to the need to quantify socioeconomic status as a five-point scale to match the original literature. See Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 for conceptual diagrams. The symbolic equation for Fig. 4 is:

where (Y) is the DV in a path, (x) is the IV, and (W) and (Z) are moderators. Table 7 displays the interaction term estimates in co-moderation. Among the 10 moderating interaction terms, two are significant. Populism would positively affect the positive relationship running from online bonding social capital to political efficacy, meaning higher levels of populism would increase the strength of online bonding social capital influencing political efficacy. Socioeconomic status, on the other hand, would negatively impact the positive association between online bonding social capital and online political engagement. This implies that in people with higher socioeconomic status, their online political engagement would be less affected by online bonding social capital. In this environment, the moderating phenomenon where we added SES was different than that of the moderated mediation model where populism was the sole moderator (interaction terms were significant in paths online bonding social capital ⇒ PE and online bridging social capital ⇒ PE). See Table 8 for hypotheses acceptance.

X IV, Y DV, W, Z moderators.

Popu populism, SES socioeconomic status, Bonding online bonding social capital, Bridging online bridging social capital, OnlineEng online political engagement, and PE political efficacy. In moderation pathways, solid lines indicate a moderating effect, and dashed lines signify no moderating effect. *p < 0.05.

Discussion and implications

Within the Taiwanese context, the above findings support the hypothesized causal relations of online social capital (both bonding and bridging) to political efficacy and online political engagement, as well as the positive association among the latter two (H1-H5). Together with the affirmed mediating effect of political efficacy (H6-H7), this aligns well with the results of similar, albeit more conventional, prior studies (e.g. Liu et al. 2023; Park and You, 2021). The highlight of this section, however, lies in the ability of this study to examine the moderating effect of populism on the causal model, along with the effect of socioeconomic status (SES) in the case of Taiwanese populist politics.

Taiwanese populism on online social capital and political efficacy

The moderating effect of populism on online social capital is validated in our moderated mediation analysis, with the cases of both bonding and bridging to political efficacy being significant (H8 and H10). However, the nature of the populist effect on the two associations differs, as the effect of online bonding social capital on political efficacy increases, while the effect of online bridging social capital decreases. The distinct political features of Taiwan may offer the most reliable account for this discrepancy between the two types of social capital. With research data for this study collected in 2022, right before the Local Elections in November, and with participants’ eyes foreseeably fixed on the General Election in January 2024 (comprising both presidential and legislative phases), this study should be contextualized within the Taiwan party-dominant political dynamics.

While conventional means still play a part in political campaigns, Taiwanese politicians have shifted to online platforms as their major arena, efficaciously mobilizing the population to engage in electoral participation. The reliance and importance of involvement in online politics for present-day Taiwanese political figures and parties have already been addressed in various studies (e.g. Lin et al. 2023; Liu, 2022; Zhong et al. 2022). This could be further evidenced by the sizeable social media followings of the three presidential candidates, with Ko Wen-je, standing for the TPP, boasting 2.2 million followers on his official Facebook account, and 1.1 million on Instagram.

Addressing the five key populist elements as defined by Engesser et al. (2017), Liu (2022) highlighted the tendency of online discourses to “attack [opposing] elites” and “ostracize others” in the last run of elections (from the 2018 Local Elections to the ouster of then Kaohsiung mayor Han Kuo-yu in 2021). The populist atmosphere in Taiwan has been radicalized by the two party-led political powers of the DPP and KMT. The former sought to engage its supporters by emphasizing the local Taiwanese identity and vilifying opponents as traitors of the country, while the latter strategized to galvanize supporters among the unemployed and unskilled workers due to economic insecurity in the late 2010s (Krumbein, 2023).

Fast-forwarding to the 2022 and 2024 elections, the three-way campaigns featuring DPP, KMT, and TPP, only served to intensify online populism. TPP, for instance, states on its official website and social media that “reform is an obligation as the new party-state becomes a reality” and “the grassroots must take over the untrustworthy regime” (Taiwan People’s Party, 2024). Although the TPP fell short in the Presidential Election, it is undeniable that it edged ever closer to success, with Ko Wen-je garnering 3.69 million votes, or 26.46% of the total, just barely losing out to the elected president Lai Ching-te’s 5.59 million votes, or 40.05% (Central Election Commission, 2024). The electoral success of TPP was largely driven by its rising popularity among Taiwanese young adults (Hioe, 2024; Nachman, 2024). The TPP’s mobilization of supporters through unconventional means, engaging them in the online sphere before remerging with traditional campaign routes, proved unexpectedly successful—not only for the TPP but also for its opponents. It thus seems the growing power of populism, facilitated by the online context, is only continuing to serve as the resolution of Taiwanese politicians to articulate their ideologies.

Explaining online social capital under populism: bonding over bridging

Revisiting the manifestation of online social capital under populism, we see that whereas the association between online bonding social capital and political efficacy is strengthened, the connection with its bridging counterpart degraded (H8 and H10). This can likely be explained with the mechanism of politics in Taiwan. Bonding social ties, either among peers or established with political figures, has proven significant with the prevalence of populism in Taiwan (e.g. Jhang, 2021; Zhong et al. 2022). This could be further traced to the emphasis on daily interpersonal contact in Chinese communities, which Son (2013) recognizes as one of the major differences between Chinese and Western forms of cultivation of social capital. Bonding social capital is characterized by its inner-oriented nature, which aligns with the populist focus on solidarity among “the people” (Page-Tan, 2021). In practical terms, this connection is evident in how Taiwanese politicians effectively mobilize their supporters through online platforms, establishing strong, emotionally charged communities. Despite their virtual nature, the formation of these online communities enables in-group political exchanges (Park and You, 2021). Moreover, family and spousal ties, which are crucial sources of social capital in Taiwan, play a significant role in this dynamic (Son, 2013). Characterized by some as “family politicization” (e.g. Ichilov, 1988; Van Liefferinge and Steyvers, 2009), the close familial bonds, within and across generations, not only amplify the influence of populism in political discussions, but also lead to likenesses in political attitudes and values, as well as efficacy.

The bridging of online social capital, on the other hand, requires individuals to utilize weak-tie networks and widen, discover, or devote themselves to new but unfamiliar perspectives, process which often have to be fostered with the help of organizations (Granovetter, 1973; Putnam, 2000; Sajuria et al. 2014). It is essentially inclusive, involving weaker but crucial ties that connect people to diverse information and facilitate exchange across different networks (Page-Tan, 2021). As elaborated by Liu (2022), populism is reflected in the nature of Taiwanese politicians using online platforms to engage in attacking opposing elites and ostracizing others (Liu, 2022). As a result, bridging online social capital is likely to be weakened with populism encouraging individuals to retreat into their in-groups and view those outside their group with suspicion. Moreover, with the party-dominant politics in Taiwan, the clear-cut boundary between political parties (typically KMT vs. DPP vs. TPP) only weakens, if not discourages, intergroup exchanges. “The people” under populism, therefore, are less likely to engage in communication with politically heterogeneous groups, reducing their ability to build bridging social capital and, consequently, diminishing the potential for developing political efficacy through these broader interactions. Based on Engesser et al.’s (2017) notion, the sovereignized and emotionalized elements constituting populism run contradictory to the embodiment of online bridging social capital, thereby lowering its effect on political efficacy.

From these interpretations, likeness is the key to online social capital situated in populism, and especially essential in the emotional-based party dynamics of Taiwanese politics. Populist ideology, as our study proves, is bond-dependent and is transmitted “from one like-minded person to another” (Engesser et al. 2017, p. 1119).

Socioeconomic status the only influence on online political engagement

Notably, while populism does possess moderating effects, its impact on the paths pertaining to online political engagement is found to be insignificant. This is the case in our moderated mediation model (H9, H11, H12), and is further reaffirmed in our co-moderation model (H14, H16, H17). The significance of the moderating effect of populism on efficacy but not engagement is that it can help explain the predominance of conventional political participation in Taiwan in the form of elections, sit-ins, and protests, as compared with its online counterpart. While the populist ideology, as observed by Engesser et al. (2017), manifests in online contexts, it does not directly lead to higher levels of online engagement. That is to say, in terms of its significance and role in the embodiment of the party-dominant and electoral politics in Taiwan, while the potential for populism to affect individuals’ efficacy is ubiquitous across the Internet, it may tend to steer individuals toward conventional participation rather than taking action online, which might explain its insignificance in influencing both the effects of social capital and political efficacy on online engagement.

Conversely, SES, instead of populism, serves as the sole significant moderator in any engagement-related path. From the co-moderation model, we find that SES negatively impacts the positive association of online bonding social capital and online political engagement (H14). Following the civic voluntarism model of Verba et al. (1995), people with higher SES tend to have more resources (including time, money, and individual skills), and therefore, they tend to, and are better able to, be politically engaged. Such a tendency is also applicable to the case of Taiwan according to the results of previous studies (e.g. Chen et al. 2020; Wu and Chang, 2017). Our study carries this discussion from a conventional to an online setting, and illustrates the significance of SES by situating it as a moderator. While the socioeconomically privileged may not depend on the cultivation of social capital but on their own political knowledge and critical thinking skills to be involved in politics, individuals with lower SES, especially young adults such as our participants, may not possess the competency to follow and understand the ongoing politics, and are consequently counting on their established bonds with peers, family, or even political figures for guidance.

Conclusion and limitations

On top of reaffirming the interrelations between online social capital, political efficacy, and online political engagement, our study uncovers the possibility of politics being studied with populism and SES as moderators instead of variables. In the specific case of Taiwan, we demonstrate the comprehensive explicability of populism in terms of understanding the interaction between individuals and party-led politics. We are also able to replicate a study in the online context that has long been unexplored, positioning both variables (dependent and independent) within the increasingly significant cyber networks.

In terms of the practical implications of our findings, particularly in the context of Taiwanese political engagement, our analysis reveals that different types of online social capital (OSC) have distinct impacts on political efficacy and engagement. Individuals with high online bonding social capital, for example, are more likely to experience enhanced political efficacy, which in turn fosters greater political engagement. This finding suggests that political actors and policymakers could strategically leverage bonding OSC to mobilize specific voter groups, particularly in a populist climate. Moreover, the influence of online bridging social capital, which connects individuals across diverse networks, highlights the potential for fostering broader, cross-cutting political engagement. In the context of Taiwan’s dynamic political environment, these insights provide valuable guidance for understanding and influencing digital political behaviors among young adults.

Unfortunately, however, our study admittedly suffers from several research limitations. First, while our research subjects comprise young adults from 20–29, other age groups who are equally, if not more, influential on Taiwanese politics are not addressed. Our data collection of HEI students may also not be sufficiently representative of all young adults aged 20–29 in Taiwan, but instead skewed towards the younger end of the age group. Second, the SES of young adults is also family-dependent, and therefore, its moderating effect should be identified among the middle-aged and elderly demographic groups whose SES will be determined as a self-dependent factor.

Lastly, it is important to note that digital platforms, such as social media networks, are not neutral facilitators of socialization and political engagement. These platforms are designed with specific affordances, algorithms, and commercial interests that can shape the ways in which OSC is formed, maintained, and mobilized. As such, the formation and impact of OSC must be understood within the context of these platform dynamics, which can involve biases and inequalities in social capital accumulation.

Our analysis, while robust in exploring the relationships between OSC, political efficacy, and engagement, acknowledges its limited scope in capturing the many nuances underpinning these platform dynamics. Future research should further investigate how different platform affordances and algorithms impact the formation of OSC and its subsequent effects on political behaviors. It would also be interesting for comparative studies on Taiwan politics to be conducted between online and offline social capital and engagements; these studies may also address cross-national contexts between Taiwan and other nations and democracies.

Responses