Toll-like receptor response to Zika virus infection: progress toward infection control

Introduction

Zika virus (ZIKV) infections are a major global public health concern1,2. ZIKV, first isolated in 1947 from rhesus macaques in the Zika Forest in Uganda3, is divided into African and Asian lineages4. In Asia, ZIKV was first detected in 1966, but its effects on public health were unknown until outbreaks in the Pacific from 2007 to 2015 began spreading throughout the Americas in 20155,6. ZIKV can infect and replicate in many cell types, including fibroblasts, keratinocytes, monocytes, macrophages, endothelial cells, neuronal cells, and glial cells7. The susceptibility and response to ZIKV infection differ based on the cell type8. Although most ZIKV infections remain asymptomatic5,9, the infection can cause severe neurological complications in adults and induce abortion in pregnant women10,11 or congenital neurodevelopmental disorders such as fetal and newborn microcephaly12,13,14,15. In rare cases, ZIKV infection is associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome, a neurodegenerative disease16.

ZIKV transmission occurs through multiple modes, including Aedes mosquito (e.g., Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus)-borne transmission, blood transmission, transplacental and sexual transmission, and organ transplant17,18,19,20. Vertical transmission of ZIKV in A. aegypti has been reported; however, its role in viral maintenance is unknown21,22. ZIKV is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus belonging to the Flaviviridae family and genus Flavivirus23. Other medically important mosquito-borne flaviviruses include dengue virus (DENV), West Nile virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, yellow fever virus, and tick-borne encephalitis virus24.

ZIKV contains a non-segmented genome of approximately 11 kb with a single open reading frame flanked by 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions23. The ZIKV genome encodes a single polyprotein that is cleaved into three structural proteins, the capsid (C), membrane (M), and envelope (E), and seven non-structural (NS) proteins, including NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS523,25. ZIKV structural proteins aid in viral particle assembly and pathogenicity, and NS proteins facilitate viral replication and avoidance of host immune surveillance26,27.

Currently, no preventive vaccines or effective treatments are available for ZIKV infection; therefore, a safe and effective vaccine is urgently required. Several potential ZIKV vaccine candidates such as live-attenuated, inactivated, nucleic acid, viral vector, and recombinant subunit vaccines have been investigated and demonstrated promising effects in clinical trials28,29,30,31,32,33. Adjuvants enhance the efficacy of vaccines in different ways, including by promoting the maturation of antigen-processing cells and their interactions with T cells and enhancing the production of different types of T helper polarizing cytokines, multifunctional T cells, and antibodies34. The development of vaccine adjuvant formulations may overcome unmet clinical needs35. In addition to aluminum salts (e.g., alum), many other adjuvants are now used clinically in viral vaccines, including CpG ODN 1018, AS04, AS03, and AS0136. Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists exhibit potential as adjuvant candidates for use in numerous vaccines, including viral vaccines, suggesting the need for further investigation of TLR agonists in ZIKV vaccine development37.

TLRs

The innate immune system functions as a crucial component of host immunity by detecting conserved microbial structures such as microbe-associated molecular patterns and pathogen-associated molecular patterns, via germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), thereby providing protection38,39,40. Different PRRs, including TLRs, retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG)-I-like receptors, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein-like receptors, C-type lectin receptors, AIM2-like receptors, and DNA-sensing receptors, are involved in recognizing viral nucleic acids and proteins39,41.

Among the different PRRs, TLRs are the most widely characterized. These molecules are encoded by a large gene family, and different organisms contain different numbers of TLRs. For example, there are 10 TLRs (TLR1–TLR10) in humans and 12 TLRs (TLR1–TLR9 and TLR11–TLR13) in mice42. TLR localization and response activity also varies in cells; TLR1/2, TLR4/5/6, and TLR10 are localized on the cell-surface, whereas TLR3 and TLR7/8/9 are in the endoplasmic reticulum43,44. Cell-surface TLRs are involved in detecting viral proteins45, whereas intracellular TLRs are involved in viral RNA or DNA detection46,47,48,49.

TLRs contain a conserved N-terminal ectodomain of leucine-rich repeats, a single transmembrane domain, and a cytosolic Toll/interleukin (IL)-1 receptor (TIR) domain38,50. The TIR domain is involved in the activation of downstream signaling, and different TIR domain-containing cytosolic adaptor proteins, including myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88), MyD88 adaptor-like (MAL or TIRAP), TIR-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing interferon (IFN)-β (TRIF or TICAM1), TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM or TICAM2), and sterile α- and armadillo-motif-containing protein, are involved in regulating TLR signaling pathways51,52,53. The MyD88 adaptor protein is involved in all TLR signaling pathways, except for the TLR3 pathway54. TLR4 and TLR3 responses can activate the TRIF pathway that finally activates IRF3. The TLR4 signaling pathway is unique and can activate both the MyD88 and TRIF signaling pathways50. TLRs play important roles in the early recognition of invaders by sensing pathogen-associated molecular patterns and subsequently inducing proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that regulate the outcome of infection by priming the immune response and providing a link between innate and adaptive immunity19,38,41,42,55.

Despite the critical role of TLRs in early recognition and protection against infections, the TLR response may act as a double-edged sword, where a dysregulated TLR response may induce an immune-mediated pathology rather than protection56,57,58,59,60,61. Therefore, a clear understanding of the role of TLRs in any infection, including ZIKV, is imperative for immunopathogenesis studies and the development of therapeutic and preventive interventions against ZIKV infection. This review discusses the current progress in understanding the host TLR response to ZIKV infection, which may lead to new therapeutic or preventive strategies. Furthermore, recent advances in the use of TLR agonists as vaccine adjuvants to produce ZIKV vaccines have been described.

TLR response to ZIKV infection

ZIKV infection induces both innate and adaptive immune responses in the host. As an RNA virus, Zika viral RNA activates different PRRs, including TLRs (e.g., TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8) and RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs; e.g., melanoma differentiation-associated gene-5 [MDA-5] and RIG-I), resulting in the production of cytokines and IFNs62. Intracellular RNA virus sensors such as TLR3, MDA-5, and RIG-I can synergistically function against DENV infection, an important viral infection of the flavivirus group that shares antigenic similarities with ZIKV5,63. ZIKV infection can induce the expression of TLR3, RIG-I, and MDA5, inflammatory chemokines such as CXCL10 and CCL5, and antiviral cytokines, including IFNs, MX1, OAS2, and IFN-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15), in primary human corneal epithelial cells, which ultimately restrict viral replication20.

ZIKV strains from Asian and African lineages differ in their immune responses and pathogenesis4,64,65, suggesting a lineage-specific outcome of ZIKV infection.

Cutaneous, but not intravenous, inoculation with IL-27 played an important role in inhibiting ZIKV infection in a mouse model66. Hernandez-Sarmiento et al. reported a difference in proinflammatory and antiviral response in monocytes infected with different lineages of ZIKV, where the ZIKV Puerto Rico strain produced a higher proinflammatory response through TLR2 signaling and NF-κB activation and induced stronger IL-27-dependent antiviral activity than that against the ZIKV Nigeria strain67. In human skin cells, ZIKV induces the transcription of multiple PRRs, including TLR3, RIG-I, and MDA5, and several ISGs, including OAS2, ISG15, and MX1, resulting in enhanced IFN-β gene expression68. Notably, ZIKV is sensitive to the antiviral effects of both type I and II IFNs68. Cytidine/uridine monophosphate kinase 2, a type I ISG, restricts ZIKV replication by inhibiting viral protein translation69.

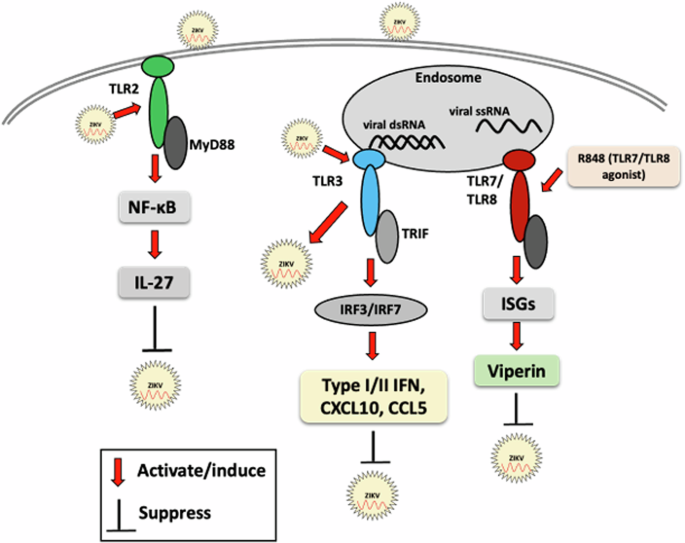

ZIKV infection induces TLR3 expression and inflammation, enhances ZIKV replication in astrocytes, and inhibits TLR3 expression, thereby reducing viral replication, suggesting TLR3-mediated pathogenesis12. Furthermore, ZIKV infection enhances TLR3-mediated inflammatory cytokine production and suppresses the IFN response triggered by RLRs in a SOCS3-dependent manner, thus facilitating virus replication70. Notably, ZIKV shares over 90% of its genome sequence with DENV17 and 55.6% amino acid sequence identity with DENV71; however, differential TLR responses have been reported72. TLR3 plays dual functions in flavivirus infection73. In contrast to ZIKV, TLR3 plays an antiviral role in DENV infection, while TLR7 provides protection against DENV and other flavivirus infection72,73. For further details of TLR response to flavivirus infection, readers may refer to previously published reviews72,73,74. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the TLR7 gene (rs179008) increase the severity of microcephaly in children with congenital Zika syndrome75, suggesting the importance of the TLR7 response in inhibiting ZIKV infection. Xu et al. demonstrated that IFNɛ-deficient mice exhibited abnormalities in the cervicovaginal tract, and intravaginal administration of recombinant IFNɛ protected IFNɛ-/- mice and highly susceptible type I IFN receptor 1-deficient (IFNAR1-/-) mice against vaginal ZIKV infection, suggesting the antiviral role of IFNɛ against ZIKV infection76. An overview of the TLR response to ZIKV infection is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Red arrows indicate the activation of TLR signaling molecules by ZIKV or its components, resulting in enhanced or reduced ZIKV infection. Black lines indicate the suppression or inhibition of the host innate immune response or ZIKV replication, as appropriate.

TLR agonist as therapeutic tool inhibiting ZIKV replication

The TLR7/8 agonist R848 (resiquimod)-induced antiviral protein viperin can inhibit ZIKV replication in myeloid cells by preventing the synthesis of viral RNA and proteins, suggesting that TLR agonists can be developed as prophylactic or therapeutic tools for treating ZIKV infection77.

Autophagy is an important component of the innate immune response that interacts with PRR signaling, leading to IFN production, and is used to defend against viral infection78. Numerous studies have demonstrated that immune signaling cascades are regulated by autophagy79. TLR signaling may induce autophagy primarily by enhancing the formation of autophagosomes and may enhance viral recognition and modulation of downstream synthesis of inflammatory cytokines80,81. Autophagy is involved in numerous viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus-1, influenza A virus, herpes simplex virus-1, and ZIKV81. During viral infection, TLR activation induces autophagy to promote IFN production; however, negative regulation of autophagy may cause termination of TLR signaling78. Autophagy also coordinates adaptive immunity. However, the ability of viruses to hijack and subvert autophagy renders autophagy a double-edged sword78. Despite the potential of autophagy to limit ZIKV replication, ZIKV can inhibit the Akt-mTOR signaling pathway in human fetal neural stem cells to induce autophagy, increasing virus replication and impeding neurogenesis82.

TLR agonist as adjuvant for ZIKV vaccine development

The whole virus can be used as a vaccine after attenuation or inactivation; however, several challenges, such as safety concerns, reduced immunity, and time-consuming manufacturing processes, limit its extensive use83,84. Additionally, poor immunogenicity remains a constraint in the development of effective peptides and DNA vaccines. To overcome these limitations, adjuvants have been used as vaccine components. TLR agonists represent a new toolbox in vaccine research, providing both immunomodulatory and immunotherapeutic effects85,86,87.

Respective TLR agonists that could be used as adjuvants in vaccines could activate specific TLR signaling pathways that culminate in the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB or interferon (IFN) regulatory factor (IRF), thereby regulating immunomodulation49. TLRs are crucial components in inducing dendritic cell maturation, regulating multiple dendritic cell functions, and providing links between innate and adaptive immunity88,89, highlighting the significance of the incorporation of TLR agonists in vaccine development. TLR ligands can enhance the antigen-processing of cells and trigger different Th responses90. A strong activation of the innate immune system is critical for the maturation and activation of immune cells as well as for the production of cytokines and chemokines to induce a potent adaptive immune response91.

Numerous investigations are currently in progress to develop effective adjuvant systems with TLR agonists to enhance the immune response and vaccine efficacy37,92. The use of TLR agonists as vaccine adjuvants to enhance vaccine efficacy has exhibited potential in various viral infections, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus -1, influenza virus, and severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus -256,93,94,95,96. In a phase III study, HEPLISAV-B, an HBV vaccine candidate, induced the rapid and consistent production of high antibody titers with sustained seroprotection with fewer immunizations, including poor vaccine responders97.

TLR agonist adjuvants may enhance the protective capacity of flavivirus vaccines and broaden antiviral antibody responses at reduced doses98. Consequently, it is considered that the use of TLR agonists could be a promising approach toward developing an effective ZIKV vaccine and enhancing ZIKV vaccine efficacy. Several well-studied TLR agonist adjuvants, including triacylated lipopeptides (e.g., Pam3CysSerLys4 [Pam3CSK4]) and their derivatives for TLR1/2, poly I:C (synthetic dsRNA) for TLR3, bacterial lipopolysaccharide or monophosphoryl lipid A for TLR4, bacterial flagellin for TLR5, imiquimod and resiquimod (nucleoside analog) for TLR7/8, and CpG ODN for TLR999, should be investigated for their potential use in ZIKV vaccine development100. In a previous study, West Nile virus (WNV) recombinant E-protein vaccine adjuvanted with TLR4 agonist SLA or the saponin adjuvant, QS21, was observed to induce long-lasting immune responses, providing sterilizing protection following WNV challenge and reduced viral titers to undetectable levels in preclinical models of Syrian hamsters98. TLR4 agonist was also demonstrated to enhance the efficacy of chikungunya virus vaccine101. Recently, using an immunocompetent mouse model, Shin et al. observed an enhanced immune-inducing potential of a plant-based recombinant ZIKV envelope protein vaccine when adjuvanted with CIA09A that contains cationic LMP, a TLR4-agonist deacylated low-fat sugar, and cholagogue saponin fraction QS-21102. CIA09A addition was reported to enhance both humoral and cellular immunities, including increased antibody production and the generation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and their effector cytokines production such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-4, and IL-6102.

DENV and ZIKV are closely associated. Therefore, understanding the mechanisms involved in the regulation of immune-mediated protection or pathogenesis during DENV and ZIKV infections is essential for developing therapeutic and preventive interventions for DENV and ZIKV infections17. Antibody-dependent enhancement remains a major obstacle in the development of DENV vaccines19, and challenges in the case of ZIKV vaccines cannot be excluded. A recent study reported that antibodies against the third domain of the envelope protein can induce neutralizing antibodies, with no evidence of antibody-dependent enhancement in other viral strains103. A ZIKV envelope recombinant protein production system was reported to enhance the development of a ZIKV subunit vaccine platform104.

Overall, the appropriate selection of specific pattern recognition receptor ligands (adjuvants) is crucial for formulating next-generation vaccines aimed at an efficient adaptive immune response with minimal side effects. Both existing and newly developed viral vaccine candidates could benefit from the judicious use of TLR agonists in vaccine formulation as vaccine adjuvants. Moreover, the use of multiple TLR agonists as adjuvants can enhance the immune response105. Therefore, further studies are warranted to explore the use of multiple TLR agonists and their effects in ZIKV vaccine formulations. Additionally, the potential of TLR agonists as vaccine adjuvants warrants further exploration for a wide range of viral vaccines.

ZIKV vaccines in preclinical and clinical development

Currently, no licensed ZIKV vaccine is available for clinical use. Due to this unmet medical need, efforts are underway to develop different types of ZIKV vaccines for clinical use, including live-attenuated, inactivated, nucleic acid, viral-vectored, and recombinant subunit vaccines28. The ZIKV envelope (E) and pre-membrane (prM) proteins are used as primary antigens for vaccine development28.

ZIKV-inactivated vaccine or DNA vaccines candidates yielded promising results in animal models106,107. A formalin-inactivated ZIKV vaccine administered prior to pregnancy prevented vertical transmission of ZIKV infection in a murine model108. In a phase 1 study, a purified ZIKV inactivated vaccine (ZPIV) was safe and immunogenic, and the highest seroconversion was observed in flavivirus-naïve individuals, followed by those primed with a Japanese encephalitis virus or yellow fever virus vaccine following the 3rd ZPIV dose109. In several other phase 1 studies, ZPIV was also found to be safe, well-tolerated, and immunogenic, exhibiting potential for further clinical development30,110.

A synthetic DNA vaccine consisting of the ZIKV pre-ME proteins produced antigen-specific cellular and humoral immunity with neutralization activity in mice and non-human primates111. Additionally, upon viral challenge, IFN-α/β receptor-deficient vaccinated mice exhibited 100% protection against infection-associated weight loss, death, and brain pathology111. A DNA vaccine encoding ZIKV NS1 was demonstrated to confer rapid protection against systemic ZIKV infection in immunocompetent mice112. A phase 1 study revealed that two DNA vaccine candidates were safe and immunogenic113. A recent study investigated the efficacy of four DNA vaccine constructs comprising full-length prM/M and E proteins, including ZK_ΔTMP, LAMP/ZK_ΔTMP, ZK_ΔSTP, and LAMP/ZK_ΔSTP33. ZK_ΔSTP vaccine candidate was more immunogenic compared to other counterparts and induced high cellular and humoral response in C57BL/6 adult mice, with high neutralizing antibody titers33. In a phase 1 clinical trial, GLS-5700, a synthetic DNA vaccine encoding ZIKV prME proteins, was safe and produced nAbs114. Additionally, passive transfer of post-vaccination sera resulted in 92% protection of IFNAR−/− mice after viral challenge with a lethal dose of the ZIKV-PR209 strain114. ZIKV DNA vaccines have exhibited promise against ZIKV infection; however, further clinical developments are needed to confirm their effectiveness in humans.

mRNA vaccine technology appears to provide a simplified, flexible, and fast vaccine production platform115. Several preclinical studies have indicated the potential of lipid-nanoparticle (LNP)-encapsulated modified mRNA (mRNA-LNP) vaccine encoding ZIKV prME proteins in producing high nAb titers, and they were demonstrated to protect against ZIKV infection and confer sterilizing immunity in mice and non-human primates32,116,117. Essink et al. reported the findings of two randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging, multicenter, phase 1 trials of the mRNA-based ZIKV vaccine, where both candidate vaccines (mRNA-1325 and mRNA-1893) administered in a two-dose schedule were well-tolerated; however, their immune responses differed118. The mRNA-1325 vaccine at three dose levels (10, 25, 100 μg) induced poor ZIKV-specific nAb responses, whereas the mRNA-1893 vaccine at four dose levels (10, 30, 100, or 250 μg) induced robust ZIKV-specific nAb responses, independent of flavivirus serostatus, that persisted until month 13118. The promising findings support the continued development of mRNA-1893 against ZIKV. A phase 2, randomized, observer-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-confirmation study of the mRNA-1893 vaccine in adults aged 18–65 years living in endemic and non-endemic flavivirus areas was conducted to evaluate its safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity; however, these data have not been published (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT0491786). Overall, mRNA-based ZIKV vaccine development exhibits significant potential for providing immunity against ZIKV and warrants further clinical investigations.

Various viral vectors, including lentiviruses, retroviruses, adenoviruses, and adeno-associated virus vectors, can be used for vaccine development to infect host cells and enhance both humoral and cellular immune responses119,120. A non-replicating adenoviral vector type 26 (Ad26) encoding ZIKV M-Env antigens induces ZIKV-specific CD4+ and CD8 + T-cell responses and produces ZIKV-specific neutralizing antibody (nAb) that protects mice and non-human primates against ZIKV challenge121. Kurup et al. developed a virus-vectored ZIKV vaccine using measles vaccine (MV) vectors expressing ZIKV-E or ZIKV-E/NS1, revealing that dual-antigen vaccines (MV-ZIKV-E/NS1) could eliminate ZIKV from the female reproductive tract, thereby enhancing protection through NS1 antibodies122. MV-ZIKA and MV-ZIKA RSP also provided protection in infant rat fetal models and reduced fetal viral loads123. The baculovirus-based ZIKV virus-like particle vaccine was safe and effective, eliciting neutralizing antibodies and virus-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) with potent memory T-cell responses124. Viral vector-based ZIKV vaccines exhibit promise and could be utilized for clinical development.

In contrast to traditional vaccination approaches, oral dissolving films or mucoadhesive film technology, a new concept in the field of pharmaceuticals for vaccine studies, has exhibited significant potential in microparticulate ZIKV vaccine administration via the buccal route125. Robust humoral (IgG, subtypes IgG1 and IgG2a) and T-cell responses (CD4 + /CD8 + ) were observed in vivo for ZIKV-specific immunity125. Cibulski et al. demonstrated that the ZIKV-E domain III recombinant protein nano adjuvanted (Quillaja brasiliensis-based saponin) vaccine-induced increased production of anti-ZIKV IgG, IgG1, IgG2b, IgG2c, and IgG3 compared to that of the alum-adjuvanted vaccine or unadjuvanted vaccine126. Overall, different approaches are currently being pursued for the development of ZIKV vaccines, and the advancements in the clinical development of ZIKV vaccines are summarized in Table 1.

Conclusion

The association between TLR responses is crucial for investigating ZIKV infections. The TLR response in viral infections may act as a double-edged sword and a balanced response is critical for the overall benefit to the host. The development of a safe and efficacious vaccine that is equally effective against the Asian and African lineages of ZIKV will benefit from a more comprehensive understanding of host innate immune responses, particularly the interactions between TLRs and viral components. A thorough understanding of TLR responses is essential for targeting TLR in therapeutic and prophylactic interventions. TLR agonists have also demonstrated significant potential as vaccine adjuvants to enhance ZIKV vaccine efficacy. However, further studies are required to identify more suitable TLR agonists as vaccine adjuvants.

Responses