Too old for healthy aging? Exploring age limits of longevity treatments

Introduction

Energy metabolism as an important modulator of longevity

Aging is characterized by progressive functional and molecular impairments, that occur at different rates across and within species. These alterations known as hallmarks of aging are reviewed in detail in refs. 1,2. Whether aging is programmed or stochastic is still under debate3,4, but defined genetic and environmental factors are known to influence the rate of aging, opening avenues for modulation of organism’s longevity.

The different approaches to extending the organism’s lifespan include genetic interventions, such as mutations in the growth hormone receptor (GHR) or insulin/ insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) receptor pathways5,6, drugs such as metformin or rapamycin7,8, stress preconditioning such as moderate temperature stress or hypoxia9,10,11,12 and various forms of calorie restriction (CR) including intermittent fasting (IF) and fasting mimicking diet13,14,15. Despite significant progress in the development of longevity remedies in the past decade, the success of these interventions is highly dependent on physiological variables such as biological sex, genetic background, metabolism and age of the treated individual16,17,18. As a result, there are significant differences in the presence and extent of interventional benefits19,20, and it is therefore critical to evaluate the applicability of specific longevity treatments from a personalized perspective, given the variation between individuals.

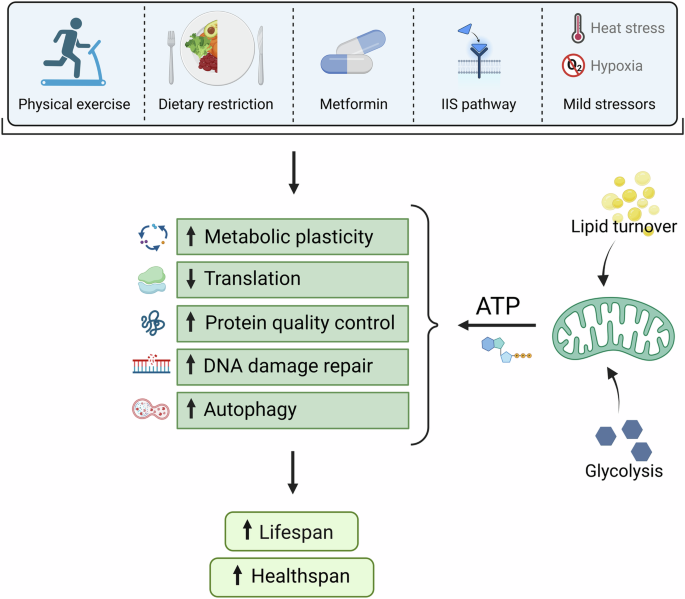

Analyzing together the studies that characterize molecular signatures of long-lived species and the well-studied longevity interventions, it is apparent that molecular pathways that drive lifespan regulation across species converge on specific cellular processes such as energy metabolism19,21, DNA damage repair22, nutrient sensing and signaling23, protein homeostasis and quality control24,25, and mitochondrial function26. Lifespan regulation in a given organism is thus subject to modulations in these cellular processes, which vary significantly among individuals. Similar to longevity mechanisms, anti-aging treatments operate through a defined array of common cellular responses including activation of sirtuins27, upregulation of autophagy and mitophagy28,29, mitigation of oxidative stress30, translational attenuation31,32 and enhancement of the adaptive stress responses33,34. While these quality control mechanisms are seemingly very different, there is a common theme among them all, which is that all these pathways require energy for the execution of their activities (Fig. 1). For example, DNA repair is a highly energy demanding process with its important player, poly ADP (adenosine diphosphate)-ribose polymerase (PARP) being among the largest consumers of nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (NAD+) in the cell35, and high levels of genotoxic stress in DNA repair deficient organisms are linked not only to premature aging but also to significant rewiring of systemic energy depots36 and metabolic remodeling37 demonstrating the important link between metabolism and DNA repair. Similarly, protein quality control systems such as chaperones and the proteasome are major energy consumers38 with decline of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis during aging being a key limiting factor for chaperone efficacy39. Given that up to 60% of cellular ATP depot is invested into ribosome biogenesis and protein translation40,41, the extension of lifespan by the attenuation of these activities may be explained by energy saving at least in part.

The figure provides an overview of the current interventions that effectively extend lifespan and improve organ function during aging. The common mechanistic targets of these interventions are summarized, and the key dependence of these downstream adaptive processes on the efficacy of energy metabolism and mitochondria is highlighted.

Energy metabolism therefore stands out among longevity mechanisms since it dictates the outcomes of other cellular responses by controlling the energy reservoir. And unsurprisingly, metabolic dysfunction underlies the progressive loss of cellular health, and deterioration of tissues, leading to impaired organismal function, and elevated mortality risks42. Mitochondria, organelles that largely control the energy status of the cell are not only regulatory units of many metabolic processes, but also crucial instigators of the development and progression of aging-associated diseases42. A growing body of evidence connects aging-driven functional impairments to the imbalance between cellular energy supply and demand43,44, which can be improved by interventions that directly or indirectly target energy metabolism.

In this context, it is noteworthy that the most reliable, robust and long-known interventions for healthy aging all target energy metabolism in one way or another. For example, the attenuation of the growth hormone (GH) signaling elicits lifespan extension across species by shifting energy resources from growth towards repair activities45. Similarly, various forms of dietary restriction (DR) such as intermittent fasting (IF), time-restricted feeding (TRF) and calorie restriction (CR) act in large part by increasing metabolic resilience of the cells and their ability to swiftly alternate between metabolic substrates for energy production known as metabolic plasticity46. Same is true for DR mimetic drugs like metformin19. Finally, one of the most promising longevity drugs, rapamycin is thought to exert its anti-aging effects by attenuating translation and upregulating autophagy47,48. However, recently we and others found that rapamycin treatment also stabilizes cellular energy expenditure, likely by shutting down energy demanding activities such as ribosome biogenesis, thus reducing metabolic pressure and protecting mitochondria from stress19,49,50.

While offering a perfect entry point for longevity modulation, as seen from above examples, reliance on metabolic plasticity can also be a weakness. For example, we and others recently demonstrated that the efficacy of DR and DR-mimetic interventions like metformin strongly depends on mitochondrial fitness51,52,53, limiting their benefits in mitochondrial mutants and in old organisms affected by aging-associated mitochondrial dysfunction19,54. In addition, the ability to rapidly activate glycolysis, which is essential for metabolic plasticity, also declines with age contributing to loss of metformin benefits in old Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans)19,55. Similar blunting of the adaptive benefits by mitochondrial aging was seen also for aerobic exercise56. And even life-prolonging impairments of insulin/IGF-1 signaling (IIS), which strongly influence metabolism and rely on modulation of mitochondrial resilience29, are most effective early in life57. Collectively, are metabolic longevity treatments mostly applicable in young organisms, or is there a path to deliver metabolic healthspan benefits also to older individuals? In this review, we will discuss this important question in detail and in the context of the current literature.

Chapter 1: Reduced metabolic plasticity limits the effectiveness of metabolic stress-based interventions at old age

It is noteworthy that some of the most effective interventions that prolong life and reduce the prevalence of aging associated diseases operate by inflicting moderate metabolic stress in the organism’s cells. The stress adaptation of the cells then underlays the pro-longevity effects of these interventions. The key examples of such remedies can be seen below.

Aerobic exercise

One of the longest known and the most robust ways of improving health and extending lifespan is physical exercise. Its applications for boosting health in humans go as far as ancient Greece58. Recently, exercise has been found to elicit a 30–35% reduction in all cause human mortality59,60 and its capacity to enhance life expectancy in humans has also been observed61. Experimental studies in animal models revealed the mechanistic basis of these positive outcomes. For example, a study in C. elegans revealed that exercise elicits transient fragmentation of the muscle mitochondrial network, which confers fitness benefits in a manner dependent on the activity of the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)62. Other studies observed mitochondrial changes not only in the muscle but also in the brain of exercising mice63,64, and shifts in mitochondrial respiration were found in the human muscle following aerobic training65, identifying mitochondria as a key target of exercise. Because mitochondrial fission is often associated with mitochondrial stress66, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) known to be produced by stressed mitochondria were found to play a key role in the effects of exercise67, it is reasonable to link the benefits of exercise to its ability to inflict reversible metabolic stress. The key adaptive responses induced by endurance exercise (the most common form of aerobic training) include inhibition of target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling, boosting of mitochondrial biogenesis, remodeling of triglyceride (TAG) expenditure and activation of autophagy68,69,70. All of these cellular changes are well known to be associated with long and healthy life, and all of them can be triggered by mitochondrial stress19,51,52.

Dietary restriction

Dietary interventions are known to humans for nearly as long as exercise71, and the first scientific evidence of life extension in a model organism (rats) by a form of dietary restriction (DR) called calorie restriction (restriction of calories without malnutrition) was published as early as 193572. Since this first publication, new forms of DR were developed such as intermittent fasting or time restricted feeding (both referring to feeding restricted to specific hours during the day)73, as well as diets lacking specific nutrients such as low carbohydrate diet (reducing specifically the proportion of carbohydrates74) and ketogenic diet (low carbohydrate and high fat diet75). Notably, when caloric restriction (CR) is performed in mice, it is often hard to disentangle the effects of reduced calorie intake from the effects of fasting, because the animals consume the limited food within ∼2 h from its provision followed by self-imposed fasting for ∼22 h. A recent study used small food pellets to either evenly distribute the restricted calorie intake over the 24 h period, or induce controlled 12 h fasting periods in combination with CR. Interestingly, while calorie reduction was alone sufficient for improving longevity in mice, the strongest effect was reached by combining CR with 12 h fasting during the active phase of the circadian cycle76, emphasizing the importance of dietary timing. While the different types of DR may appear distinct, they all have a common mode of action of limiting the availability of nutrients to the cells thus forcing cells to mobilize internal nutrient reserves and/or switch to using an alternative set of substrates for ATP synthesis, thereby improving the ability of the tissues to swiftly alternate between energy sources known as metabolic plasticity77,78. The mechanisms driving metabolic plasticity in the case of DR are similar to the effects of exercise and include mitochondrial fission and fusion, changes of mitochondrial bioenergetics, AMPK activity and remodeling of lipid metabolism53,79. These mechanisms are functionally important in driving the effects of DR as seen by, for example, the failure to achieve DR benefits in AMPK deficient animals80.

DR mimetic drugs

Because dietary interventions are physically challenging and require strict compliance, as soon as the mechanisms linking DR to improvements of health and longevity became evident, the pharmacological compounds, which replicate some of the molecular DR effects were put forward and referred to as DR or CR mimetics81. Among the many available DR mimetics some act by enhancement of autophagy and/or mitophagy – including spermidine, curcumin and urolithin A82,83, some such as rapamycin replicate effects of nutrient sensing by inhibiting TOR81 and others like metformin act by limiting mitochondrial effecacy19,84. Although the direct cellular targets of metformin are still under debate52,84,85,86, with cellular effects possibly depending on its concentration85, at least some studies demonstrate metformin to be an inhibitor of electron transport chain (ETC) complex I84,86,87. Through its interaction with mitochondria, metformin can mimic a very large array of DR effects such as mitochondrial fission and fusion, induction of autophagy, remodeling of lipid metabolism, oxidative stress responses and attenuation of protein translation7,19,51. Just like its targets, the efficacy of metformin in extending lifespan and healthspan is controversial. It was found to improve longevity of C. elegans very successfully7,19,51 but failed to do so in Drosophila melanogaster (D. melanogaster)88. An NIA Interventions Testing Program (ITP) study initiating metformin treatment at nine months of age showed no significant life span extension (https://phenome.jax.org/itp/surv/Met/C2011), while another independent study initiating drug treatment at twelve months of age showed clear longevity improvement89. At the same time, metformin effectively supported neuronal integrity and function in mouse models of aging-linked neurodegenerative diseases (Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease)90,91,92, and during aging in healthy mice93. Finally, a recent study showed cognitive benefits and deceleration of epigenetic aging by metformin in male primates94. Collectively, an evident variability in metformin induced longevity benefits is seen between different models and studies, but overall, it still holds promise as an anti-aging drug given that the mechanisms, which drive variation, can be understood and reliably controlled.

Attenuation of the insulin/IGF-1 receptor signaling

To answer the debate of whether aging can be genetically controlled, the first genetic mutants that prolong lifespan were discovered in late 1990s – early 2000 in C. elegans and D. melanogaster95,96,97,98. Interestingly, large percentage of the discovered genes were implicated in energy metabolism. For example, the C. elegans clk-1 and isp-1 genes encode components of the mitochondrial ETC, and their partial loss of function was found to prolong lifespan by triggering moderate mitochondrial stress97, similar to the above described effects of exercise and DR. The partial loss of function of the nematode daf-2 and age-1 genes in turn interfered with the IIS pathway, which integrates systemic nutrient states with cell-autonomous adaptive responses95. In fact, inactivation of daf-2 is among the strongest lifespan extenders ever discovered, leading to doubling of lifespan in C. elegans6,99, while in mice, some of the most significant lifespan extensions, as well as improvements in cognition and glucose tolerance, have been linked to spontaneous or experimentally induced mutations that impair GH biosynthesis, GH function, or IGF-1 sensitivity13,100,101. In fact, GH receptor knockout (GHRKO) mice have received the Methuselah longevity prize, holding the record for the longest-lived laboratory mouse at 1819 days (nearly 5 years, compared to the typical lifespan of 2–2.5 years)102. Notably, GH/IGF-1 pathway is downregulated by dietary restriction, with DR and GH/IGF-1 inhibition triggering similar longevity programs13. By using drug-inducible gene disruption, it was shown that inactivation of the GHR gene from mature adulthood improves metabolism and extends lifespan in mice102. In C. elegans, disruption of the insulin/IGFR pathway in neurons or intestine was effective in extending lifespan99,103, but such tissue-specific effects were not matched by mouse tests. Intestine specific ablation of GHR had little effect on both the intestine and the homeostasis of the whole body, while inactivation of GHR in specific neurons did not confer positive organismal changes but instead impaired the response of the mice to caloric restriction making them lose too much energy and weight during this treatment104. This comparison indicates that while pro-longevity effects of inhibiting insulin/GH/IGF-1 axis exist across species, some features of this response differ between vertebrate and invertebrate models. The molecular mechanism linking IIS inhibition and longevity is complex and involves boosting of adaptive stress responses via the DAF-16/Forkhead box protein O (FOXO) transcriptional activity (like antioxidant response) or independently of DAF-16/FOXO (like autophagy, AMPK- and TOR-regulated responses)105. But notably, it was recently found that IIS inactivation profoundly affects mitochondria, causing mitochondrial stress and accelerated mitochondrial turnover as well as changes in fission and fusion and mitochondrial ATP output29. Moreover, the defects of mitochondrial biogenesis abrogated life extension by inactivated daf-229, suggesting that mitochondria are among upstream sensors of metabolic stress instigated by IIS deficiency, orchestrating the downstream adaptations and longevity boosting. In line with cross-species mitochondrial involvement, hallmarks of mitochondrial biogenesis were observed also in tissues of GHRKO mice106.

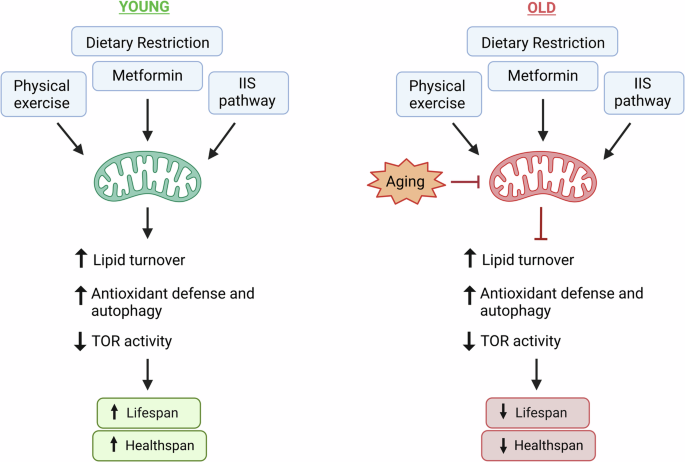

The above examples thus demonstrate that induction of moderate metabolic and especially mitochondrial stress are among most effective ways to prolong life. However, the reliance on mitochondria may be a source of limitations. For example, an early study using RNAi-mediated gene inactivation demonstrated that ablation of the IIS pathway does not extend lifespan of C. elegans when initiated at post-reproductive age57. At the same time, treatment with the monoclonal antibody against IGF-1R improved healthspan and increased lifespan in female mice treated at 18 months of age (with typical lifespan being 26–30 months)107, and recent studies in nematodes found that degron-driven DAF-2 inactivation during late adulthood is effective in lifespan extension108,109. In humans, GH/IGF-1 levels are naturally decreasing with age, and clinical hazard including outcomes like mortality and dementia, increases at both high and low circulating IGF-1 levels110. It is thus plausible that the outcome of the insulin-1/GH/IGF-1 axis ablation at old age is context-dependent. In this context, we and others recently found that aging associated mitochondrial dysfunction limits the lifespan benefits of DR, DR mimetic metformin and exercise in late life19,54,56. Metformin for instance enhances metabolic plasticity for healthy aging in young C. elegans but causes acute energy exhaustion and lethality in older nematodes and human cells with impaired mitochondria (Fig. 2). Genetic or toxin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction can also trigger metformin toxicity, regardless of age, emphasizing the importance of mitochondria in this effect. Notably, treatment from young adulthood to the end of reproduction maximizes longevity benefits without requiring lifelong exposure19. These observations suggest that interventions relying on mitochondrial and metabolic stress for their pro-longevity outcomes may lose efficacy during aging due to mitochondrial dysfunction and disrupted metabolic plasticity. However, we can use the knowledge of such limitations to deliver these treatments at the age of their maximal efficacy.

The figure summarizes key interventions that promote healthy longevity by inflicting moderate mitochondrial and metabolic stress. At young age (left panel) these moderate stressors act as boosters of functional resilience for healthy aging triggering cellular remodeling towards elevated defense responses and metabolic plasticity. Conversely, at old age (right panel) these adaptive activities are blunted by mitochondrial aging leading, in case of a simple organism C. elegans, to energy exhaustion and premature death. While immediate death is not expected in more complex organisms, hints of reduced late life benefits and elevated degenerative side effects are seen also in higher species.

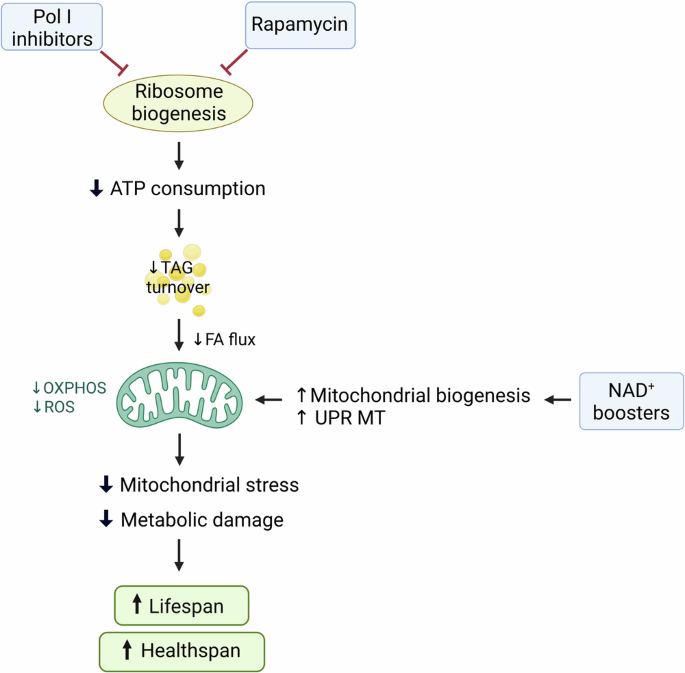

Chapter 2: Is there a solution for the elderly? Stress-reducing interventions work well late in life

Because some of the most effective longevity treatments appear to lose efficacy at old age due to aging-associated decline of energy metabolism, it becomes critical to identify interventions that act independently of age. These remedies should ideally (a) not rely on mechanisms which fail with age such as the ability of mitochondria to respond to stressors and (b) better focus on prevalent metabolic deficits of old organisms such as lowered ATP production and depletion of energy depots19,21. Interestingly, interventions that combine these two features are indeed effective at any age as discussed below and summarized in Fig. 3.

The figure lays out a mechanism, which connects the reduction of ribosome biogenesis by either rapamycin treatment or direct inactivation of Pol I to healthy longevity. As ribosome biogenesis is highly energy consuming (∼60% of total cellular ATP expenditure), its blunting liberates ATP reserves and reduces energy expenditure. Cells respond to drastically reduced energy demand by slowing down the consumption of triglyceride (TAG) reserves thus reducing the flux of fatty acids (FA) into mitochondria and dampening OXPHOS. Lowered OXPHOS levels downregulate mitochondrial stress and ROS production and thereby reduce the build-up of metabolic damage. This direct “de-stressing” of mitochondria is effective independently of age and elicits benefits even very late in life. Similar mitochondrial “de-stressing” and improvement of mitochondrial health can be achieved in both young and old organisms by supplementation of NAD+ precursors via NAD+-dependent epigenetic de-repression of the genes implicated in mitochondrial biogenesis and quality control.

NAD+ boosters

Nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide (NAD+) is structurally comprised of two covalently joined mononucleotides (nicotinamide mononucleotide or NMN, and AMP), and has its core function as an enzyme cofactor that mediates hydrogen transfer in oxidative or reductive metabolic reactions111. In addition, NAD+ serves as an ADP ribose donor for PARPs that are involved in DNA damage sensing and chromatin opening to initiate repair112, and it is required for the histone deacetylase activity of sirtuins to boost peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1α)-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis and expression of the protective genes implicated in mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPR MT)27,113. Thus, DNA repair competes for NAD+ depots with mitochondrial quality control mechanisms, and this competition is especially critical during aging when DNA damage increases, and mitochondrial damage increases too. In addition, NAD+ synthesis declines with age leading to NAD+ exhaustion, with up to ∼40% drop in levels detected for example in the aging mouse brain114, and direct negative impact on energy metabolism in aging113. With the discovery that organismal NAD+ levels can be improved by dietary supplementation of its precursors like nicotinamide riboside (NR) or NMN115,116, NAD+ boosting became an attractive intervention for healthy aging. Recent studies indeed show that NAD+ repletion has a potential to improve health during aging, with positive effects seen in animal models of diverse aging-associated diseases ranging from cardio-vascular disease to cognitive decline117,118. While improvements of health with NAD+ boosters are seen across organisms119, their ability to extend lifespan has been most clearly demonstrated in C. elegans by using NAD+ precursor NR113, and NAD+ precursor NAM improved aspects of healthspan but not lifespan in mice120. The discrepancy may be due to higher complexity of the mouse system compared to the worm, making life extension more complicated to achieve, but it is also plausible that the kind of NAD+ booster used plays a role, with some drugs being purer and more effective than others. In all cases however the improvement of mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial health and energy metabolism by NAD+ boosters was found to be the key driver of their positive impact113. Notably, the reinvigorating effect of NR and NMN on mitochondria is not limited by aging, with even late life treatments showing benefits121,122,123. In our view, this is because NAD+ boosting (a) targets the deficit, which is relevant in the aged cohort (e.g. NAD+ exhaustion and associated decline of mitochondrial resilience) and (b) it targets mitochondrial homeostasis very directly at the respective gene expression level without involvement of intermittent adaptive mechanisms that are instead required for connecting interventions like DR and exercise to the same mitochondrial responses. NAD+ boosters are thus promising enhancers of energy metabolism and ATP synthesis at old age.

mTOR inhibitors and rapamycin

As discussed above and similar to mitochondrial biogenesis, mTOR inhibition is an essential downstream target of interventions that act by inflicting metabolic stress. Some effects of DR, DR mimetics and exercise such as changes in protein synthesis and enhanced autophagy can be replicated by pharmacological TOR inhibitors. Rapamycin is the best known and widely used mechanistic TOR (mTOR) inhibitor, giving the name to the respective pathway (TOR stands for “target of rapamycin”). This drug was initially discovered as a strong antifungal agent produced by aerobic Gram-positive soil bacteria124, and later gained clinical attention due to its potent immunosuppressor and anti-cancer properties125,126. In parallel, genetics and functional tests in yeast and rodent tissue identified mTOR kinase as a molecular target of rapamycin, explaining the ability of the drug to reduce cell proliferation and size125,127. The complexity of the TOR pathway and its cellular effects is discussed in detail elsewhere128, while for this review it is important to note that the key role of TOR in the context of metabolic stresses is to adjust protein translation and ribosome biogenesis to the available resources of the cell. Specifically, TOR integrates diverse upstream cues such as availability of amino acids, nucleotides and free ATP with the levels of ribosome biogenesis and protein translation to prevent these two highly demanding activities from exhausting cellular reserves. The attenuation of protein synthesis by rapamycin contributes to healthy longevity by reducing protein folding stress and protein aggregation47. Additionally, TOR is a potent repressor of autophagy/mitophagy and lysosome biogenesis48,129 making yet another link between TOR inhibition, metabolic stress and longevity. Although most studies attribute rapamycin’s effects to its intracellular actions, its ability to reduce experimental colitis in mice was associated with alterations in gut microbiota composition. Moreover, autophagy induction by rapamycin was lost following microbiome ablation130. On the other hand, a study in Drosophila suggested that life-extending effects of rapamycin are independent of microbiota at least in invertebrates131. In general, the positive impact of rapamycin on lifespan and healthspan has been extensively demonstrated across species including C. elegans, Drosophila and mice8,132,133. At the level of pathology in mice, rapamycin reduces cancer, alleviates atherosclerosis and heart disease, improves blood brain barrier and reduces pathology in Alzheimer’s disease models134. And importantly, rapamycin benefits can be achieved independently of age, with even late life exposure delivering effects8. Interestingly, the lifespan extension induced by rapamycin was comparable following administration at 4, 9, or 19 months of age, and even short-term treatment in older mice, lasting only 8 weeks, resulted in long-term improvements in cardiac function, which continued weeks after the treatment had ended135. In another study three months of rapamycin treatment at middle age were sufficient to increase life expectancy by 60%136. As with NAD+ boosters, rapamycin replicates some of the DR and DR-like effects at the level of very downstream effectors and without reliance on adaptive intermediates like mitochondria, which are known to fail with age. Moreover, we recently found that rapamycin stabilizes ATP levels in old human cells and nematodes by lowering energy demanding ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis, and thus reducing aging-associated mitochondrial and metabolic stress19. In summary, rapamycin’s inhibition of anabolic activities conserves resources and reduces protein and mitochondrial stress, offering an ideal solution for aging organisms with weakened stress responses.

Polymerase I inhibitors

While rapamycin is recognized as an effective longevity drug, concerns about side effects from TOR inhibition persist. This opens the need for developing specific inhibitors targeting individual TOR targets, such as rRNA transcription by Polymerase I (Pol I)137,138. Recently, we found that inhibiting Pol I, either directly or by inactivating its co-factor TIF-1A, indeed extends lifespan in C. elegans by conserving energy used for rRNA synthesis and ribosome biogenesis. Multi-method analyses showed that tif-1a inactivated nematodes deplete triglyceride reserves more slowly than controls, particularly in middle and old age. This slower triglyceride use decreases fatty acid flow into mitochondria, downregulating oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and reducing mitochondrial stress and metabolic damage (Fig. 3). These changes decelerate metabolic aging, leading to longer life and better organ function. As shown by other groups, reduced Pol I activity also exhibits pro-longevity effects in Drosophila and humans, suggesting potential cross-species benefits139,140. These studies collectively demonstrate that inactivation of a seemingly non-metabolic process of rRNA transcription elicits a cascade of profound and complex metabolic changes that eventually prolong life. Importantly, we found Pol I inactivation to elicit longevity benefits also at very old age likely because it (a) acts upon a very downstream longevity mechanism similar to NAD+ boosters and rapamycin, and (b) it targets aging-relevant deficits such as energy exhaustion and superfluous mitochondrial stress.

Discussion

In this review we demonstrated that the majority of aging mechanisms either depend on energy and energy metabolism or regulate it or both, highlighting energy metabolism as one of the central modulators of aging. Additionally, we propose two categories of metabolic interventions for healthy aging: (1) those that elicit moderate mitochondrial and metabolic stress like exercise and metformin, with subsequent stress adaptations driving their lifespan benefits, and (2) those like NAD+ boosters, rapamycin and Pol I inhibitors, that directly modulate very downstream longevity targets and thereby reduce metabolic stress and molecular damage accumulation. While both intervention categories are highly effective, the key variable is age: the efficacy of remedies relying on adaptive resilience is often limited by the failure of mitochondria and other plasticity mechanisms later in life. Conversely, the interventions that limit energy exhaustion and molecular damage build-up by direct reduction of anabolic activities are equally effective regardless of age. Understanding these specific nuances enables us to putatively tailor the most appropriate treatment regimen for each age group. This age-adjustment concept may be an important step toward the necessary personalization of longevity treatments, because the “one drug for all” approach is likely as ineffective in longevity therapies as it is in conventional medicine.

Responses