Topological decomposition of hierarchical skyrmion lattices

Introduction

Topology provides insights into the global properties of physical systems, which plays a crucial role in modern physics and governs many physical phenomena. Topological quasiparticles like skyrmions are prominent examples regarding the topological protection under continuous deformation of the field. Initially proposed in nuclear physics1,2, skyrmions have since emerged in various physical disciplines, including Bose–Einstein condensates3,4,5, liquid crystals6,7,8, magnetic materials9,10, acoustics11, and water waves12. Skyrmionic vector fields contain all possible polarization states, with each state mapped to a point on a spherical surface. The stability of skyrmions is rooted in their topological twists13, quantified by the skyrmion number, which indicates the number of times the sphere is wrapped. Since the first observation in chiral magnets9,10, skyrmions have garnered significant attention, where the inherent stability makes them promising candidates for applications in magnetic storage technologies14,15,16.

Recently, the topological quasiparticles were observed in the realm of optics with the skyrmionic texture constructed by various vector fields17, including electromagnetic fields18,19,20,21,22,23, spin angular momentum24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 and energy flow in nonparaxial beams33, as well as Stokes vectors in paraxial beams34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. The rapid advancement of Stokes skyrmions is driven by innovations in field generation technologies, including complex field synthesis via spatial light modulators35,45, universal optical modulators46, on-chip skyrmionic beam generators47,48, and spin-orbit optical-skyrmionic wave plates49. Optical skyrmions have demonstrated strong resilience to complex polarization aberrations50, while non-local skyrmions, as quantum entangled topological states of light51, further underscore potential applications in photonic computing52, optical communication53, nanoscale metrology54 and magnetic domain imaging55.

The symmetry fundamentally constrains the topology of optical skyrmions26,29,56. In optical systems with continuous rotational symmetry, isolated skyrmion configurations with integer topological number, such as single skyrmions and skyrmionium, are typically observed24,33,34,35,38. As the rotational symmetry of the field is broken, individual skyrmions will interact and may condense in a lattice, giving rise to the formation of skyrmion and meron lattices, with the topology constrained by the symmetry. Specifically, in nonparaxial beams, 3-fold and 4-fold symmetries lead to the formation of triangle and square meron lattices with a half-integer topological number27,29,56, while 6-fold symmetry can stabilize hexagonal skyrmion lattices with integer topological number18,19,26,27,29. Although various skyrmion lattices have been observed in nonparaxial beams, such lattice configuration in Stokes skyrmion remains untapped. Different with field or spin skyrmions, the topological feature of Stokes skyrmion is embedded in the polarization texture of structured light and manipulated by the selection of Poincaré beams. This leads to a more flexible manipulation of skyrmionic textures. High order skyrmions, anti-skyrmions and bimeron that are difficult to construct in other optical system have also been realized. These complex lattice structures often encode fundamental physical properties. Decomposing them into sublattices with distinct topological characteristics offers deeper insights into their underlying behaviors and opens pathways for applications in photonics and optical communication.

In this study, we demonstrate the topological synthesis and decomposition of hierarchical skyrmion lattices. We theoretically propose and experimentally demonstrate the formation of meron, skyrmion, and skyrmionium lattices for 3-fold, 4-fold, and 6-fold symmetry respectively. Similar to case in surface waves, the topology of sublattice configuration is constrained by the symmetry of field. However, additional sets of sublattice appear in the momentum space due to the spatial propagation, giving rise to totally different topology of the primary lattice. This demonstrates the topological states transition among skyrmion interactions. Square skyrmion lattice and hexagonal skyrmionium lattice were observed, which always require specific condition to construct in condensed matter system and have not been realized in optics. The topological lattice structure was experimentally realized by the interference of optical vortices using multiple pinholes. The experimental results agree well with the theoretical predictions. By superimposing different topological lattices with varying lattice constants and specific rotation angles, it is possible to create a super-topological lattice structure that is analogous to a moiré lattice. This approach offers a way to investigate interactions between different topological phases and may lead to the discovery of previously unexplored physical phenomena.

Results

Basic scheme for the formation optical stokes skyrmion lattices

The isolated optical Stokes skyrmions with spatial variation of polarization can be constructed through a superposition of Laguerre–Gaussian (LG) modes with orthogonal polarization states34,35,41.

where eR and eL represent orthogonal right and left-handed circular polarization states (RCP and LCP), (L{G}_{p,l},) is the Laguerre–Gaussian mode57 characterized by radial and azimuthal indices ((p,l),). ({phi }_{gamma },) is the global phase difference between the two orthogonal polarization components, which controls the helicity textures of skyrmion.

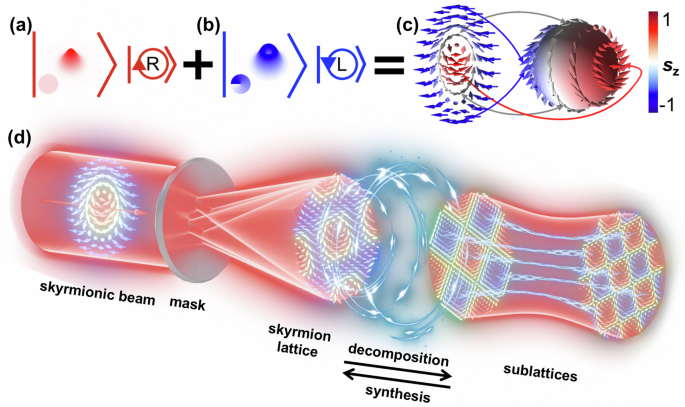

The isolated optical Stokes skyrmion, as described in Eq. (1), is illustrated in Fig. 1a–c. If the rotational symmetry of the optical field is broken, skyrmions may interact and condense in lattices. To achieve this, we modulate this isolated skyrmionic beam in Fourier space using an intensity mask with pinholes at the vertices of an equilateral N-fold polygon. This configuration generates skyrmion lattice on the transverse plane through multi-wave interference in real space, as depicted in Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the superposition of orthogonally polarized LG00 (Laguerre–Gaussian) mode (a) and LG01 mode (b) to generate an isolated skyrmion (c). Panel c also depicts the projection relationship between the skyrmion and the Poincaré sphere. The colorbar represents the Sz component of the stokes vector. d The isolated skyrmionic beam is modulated by masks with three, four, or six regularly arranged pinholes. The interference of multiple waves with different polarization states then leads to the formation of optical skyrmion lattices, which can be decomposed into hierarchical skyrmion sublattices.

The skyrmion lattice results from the interference of plane waves with different polarization states. To understand the generation principle of skyrmion lattice, we decompose these polarization states into the superposition of RCP ER and LCP EL as

where AR and AL are constants, l is the topological charge of orbital angular momentum (OAM), kr and kz are the transverse and longitudinal wave-vector components satisfying ({k}^{2}={k}_{r}^{2}+{k}_{z}^{2},) with k being the wave vector in air. N defines the N-fold rotational symmetry of the lattice. The global phase difference between the two orthogonal polarization components is denoted by θ0, which controls the helicity textures of optical skyrmion lattices. For the RCP component, the interfering plane waves have the same phase, generating an optical lattice or quasi-lattice with N-fold symmetry, as described by Eq. (2.1). Additionally, impressing an absolute phase 2πl/N onto the nth plane wave at each unit cell, forming a vortex lattice that acts as the LCP component (Eq. 2.2). Both components have identical wave vectors, differing only in phase. Superimposing these two lattice structures with orthogonal RCP and LCP enables the creation of spatially periodic polarization distributions, leading to a skyrmion lattice, as described in Eq. (2.3). The normalized Stokes vector, which constructs the optical skyrmion, can be derived from the Jones vector of the optical field (see Supplementary Note 1).

The rotational symmetry significantly influences the topology of the skyrmion lattice. It is determined by the number of interfering plane waves (corresponding to the number of pinholes in the Fourier plane), with the superposition of N waves resulting in a periodic or quasiperiodic transverse field distribution with N-fold rotational symmetry. In two dimensions, the interfering patterns can only be regularly tessellated with 3, 4 or 6-folds rotational symmetries, resulting in nontrivial skyrmion lattices. Consequently, we meticulously analyzed the topological properties of optical Stokes skyrmion lattices with rotational symmetries of N = 3, 4, and 6. Different geometric unit cell structures of the skyrmion lattice can be constructed with triangular lattices for N = 3, square lattices for N = 4, and hexagonal lattices for N = 6. By analyzing the intensity pattern in the Fourier plane, a hierarchical structure in skyrmion lattice is unveiled, where the primitive lattice contains one, two, and three sets of sublattices for N = 3, 4, and 6, respectively. The topological invariance of a skyrmion can be effectively characterized by the skyrmion number: Q(=frac{1}{4pi }iint {{{bf{n}}}}cdot frac{partial {{{bf{n}}}}}{partial x}times frac{partial {{{bf{n}}}}}{partial y}{dx}{dy}), where n represents the local unit Stokes vector. The rotational symmetry determines the skyrmion number of the unit cell of the skyrmion lattice, e.g. Q = ± 0.5 for N = 3, Q = 1 for N = 4, and Q = 0 for N = 6 for topological charge of l = 1, while different topology is embedded in each sublattice. Our results show that these specific symmetries promote unique geometric structures and topological properties within skyrmion lattices. For the sake of simplicity, we consider the case with l = 1 in the following, while similar results can be obtained for the other topological charges of vortex beam (see more details in Supplementary Note 1, Note 2, and Note 3).

Triangular meron lattice with 3-fold rotational symmetry

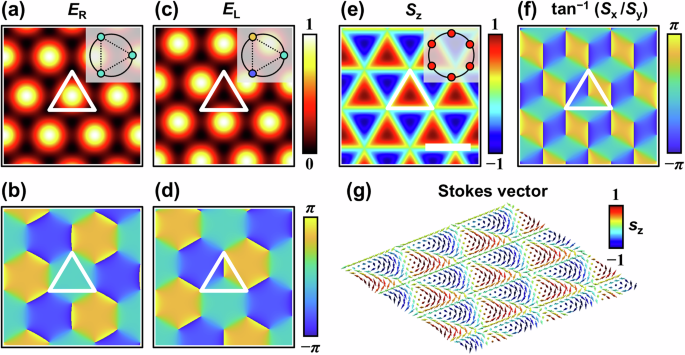

We start from the simplest case with 3-fold rotational symmetry, which will generate triangle meron lattice. We control the rotational symmetry of spectrum distribution in Fourier space to generate the optical lattices, as shown in the insets of Fig. 2a. The interfering patterns for the RCP component have no phase difference, generating a triangular lattice without vortex phase in the center of the unit cell of lattice, as shown in Fig. 2a, b. Conversely, the import of OAM for the LCP generates vortex lattices in each unit cell, as shown in Fig. 2c, d.

The intensity and phase distributions of a, b RCP (right-handed circular polarization) and c, d LCP (left-handed circular polarization) with marked triangle representing the unit cell. The insets in a and c illustrate the RCP and LCP field distribution in Fourier space, closed circles represent plane waves and color maps the relative phase. The normalized Stokes (S = [Sx, Sy, Sz]) distribution of e out-of-plane (Sz) and f in-plane component [tan−1(Sx/Sy)]. For the in-plane component, we use hue color to map the transverse azimuth from −π to π. The inset in e displays the Fourier spectrum of the Stokes vector field. g The optical Stokes orientation distribution corresponding to the top lattice showing a Stokes-meron lattice. The scale bar is 2λr/3, where λr is the transverse wavelength component.

The intensity and phase distributions of triangular lattice between the orthogonal polarizations are complementary, as shown by the marked triangle in Fig. 2a, c. This allows for a topological lattice in the superposition fields of orthogonal RCP and LCP components. The superposed out-of-plane Stokes component exhibits a triangular lattice with alternating upwards- and downwards-pointing equilateral triangles (polarity equal to ±0.5) [Fig. 2e]. The two opposite filling states results in six different vectors positioned in a hexagon in k-space, as shown in the inset of Fig. 2e. And the in-plane Stokes component exhibit Bloch type topology with vorticity equal +1 over all space, as shown in Fig. 2f. The superposition of both polarization components yields a triangular meron lattice with alternating skyrmion numbers [Fig. 2g]. A detailed derivation process is provided in supplementary Note 2.

Square skyrmion lattice with 4-fold rotational symmetry

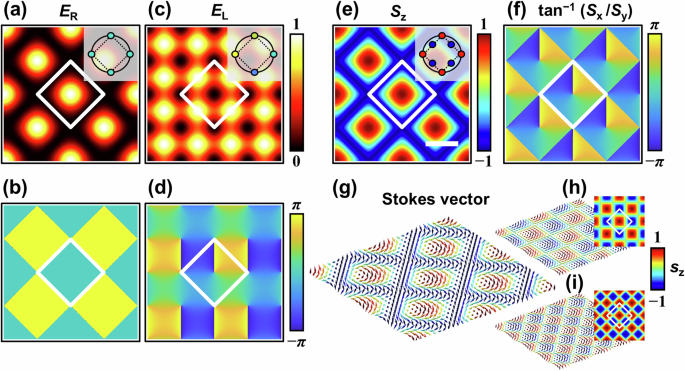

For the optical lattice with even rotational symmetry, the electric field for each circularly polarization component can be considered as a superposition of standing waves. Due to the additional π phase shift introduced by the OAM in the LCP component of counter-propagating waves, the orthogonal polarizations exhibit different interference patterns. Specially, constructive or destructive interference occurs at the center of each unit cell for the RCP or LCP component, respectively, resulting in bright or dark spots.

For the optical field with 4-fold rotational symmetry, the RCP component construct a square lattice, with the boundaries formed at the zero points of electric field, as shown in Fig. 3a, b. While the introduction of OAM in the LCP component produces a lattice structure with alternating bright and dark regions with a smaller periodicity. Uniquely, the smaller-period lattice of the LCP component can match the larger-period lattice of the RCP component, forming a complementary vortex lattice, as shown in Fig. 3c, d. In each unit cell, the Stokes vector points along positive z axis at the center and negative z axis at the boundary, with skyrmion number equal to +1, as shown in Fig. 3e, g (the detailed derivation of skyrmion number is provided in Supplementary Note 2). The interference pattern of electric field results in two distinct groups of Stokes vector in the Fourier spectrum [Fig. 3e], corresponding to two sets of sub-lattices with different topology perperties [Fig. 3h, i].

The intensity and phase distributions of a, b RCP (right-handed circular polarization) and c, d LCP (left-handed circular polarization). Marked squares represent the unit cell of the lattices. The insets in a and c illustrate the RCP and LCP field distribution in Fourier space; closed circles represent plane waves and color maps the relative phase. The normalized Stokes (S = [Sx, Sy, Sz]) distribution of e out-of-plane (Sz) and f in-plane component [tan−1(Sx/Sy)]. The inset of e show the Fourier domain spectrum, which could divide into two sets of sublattices according to the radius. g The Optical Stokes orientation distribution of primitive skyrmion lattice. h, i The Optical Stokes orientation distribution of two meron sublattices, and the insets shown the normalized Stokes distribution of out-of-plane (Sz). The size of the marked square is the same as that of the primitive lattices. The two sublattices are extracted from the inverse fast Fourier-transform (IFFT) of the lattice points in the frequency domain, specifically (sqrt{2})kr and 2kr lattice points (as further explained in Supplementary Note 2). The scale bar is λr/2, where λr is the transverse wavelength component.

From the Fourier spectrum of Stokes vector, the primitive skyrmion lattice could be divided into two sets of sub-lattices. For the lattice points located at the inner square [blue dots in Fig. 3e], the field pattern and topological lattice manifest a contraction of scale by a factor of 1/(sqrt{2}) and undergoes a relative rotation of π/4 with respect to the primitive lattice [Fig. 3h]. While another sublattice fed by the red dots in Fig. 3e displays a scale reduction of 1/2 relative to the primitive lattice [Fig. 3i]. Due to the decomposition of skyrmoin lattice, the topological properties of these sublattices diverge from the primitive lattice with each unit cell in the sublattices having a skyrmion number of ±0.5, forming meron lattices. [Fig. 3h, i] (as detailed in supplementary Note 2).

Hexagonal skyrmionium lattice with 6-fold rotational symmetry

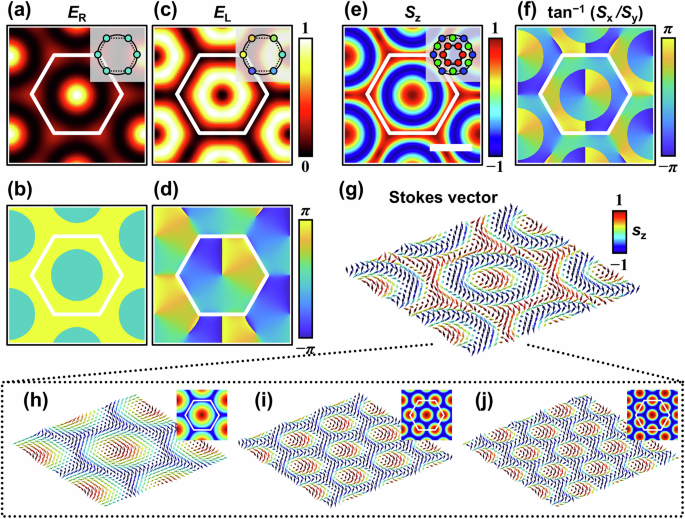

For the optical field with 6-fold rotational symmetry, a hexagonal lattice structure is formed. A dark intensity ring corresponding to a phase discontinuity within each unit cell is obtained for the RCP component [Fig. 4a, b]. In contrast, the electric field of LCP component is zero at the center and boundary of each unit cell, while a bright intensity ring can be obtained inside [Fig. 4c, d]. This leads to twice flips of Sz, where the out-of-plane Stokes vectors rotate from upwards to downwards at the phase discontinuities and then revert upwards at the boundary [Fig. 4e], resulting in a skyrmionium lattice with a skyrmion number of zero [Fig. 4g].

The intensity and phase distributions of a, b RCP (right-handed circular polarization) and c, d LCP (left-handed circular polarization). Marked hexagon visualizes the unit cell of the lattices. The insets illustrate the RCP and LCP field distribution in Fourier space; closed circles represent plane waves and color maps the relative phase. The normalized Stokes (S = [Sx, Sy, Sz]) distribution of e out-of-plane (Sz) and f in-plane component [tan−1(Sx/Sy)]. The inset shows the Fourier domain spectrum, which could divide into three sets of sublattices according to the radius. g The Optical Stokes orientation distribution of primitive skyrmion lattice. h–j The optical Stokes orientation distribution of three skyrmion sublattices. The insets shown the normalized Stokes distribution of out-of-plane (Sz). The size of the marked square is the same as that of the primitive lattices. The three sublattices are extracted from the inverse fast Fourier-transform (IFFT) of the lattice points in the frequency domain, specifically kr, (sqrt{3})kr and 2kr lattice points (see more details in Supplementary Note 2). The scale bar is 2λr/3, where λr is the transverse wavelength component.

The composition of wavevector in the Strokes vector for 6-fold rotational symmetry leads to a more complex Fourier spectrum with three sets of sublattices as shown in the inset of Fig. 4e. Sublattice 1 has the same unit cell size as the primitive lattice but exhibits a different topological property, forming a skyrmion lattice with a skyrmion number of 1 [Fig. 4h]. Sublattice 2, on the other hand, is scaled down by a factor of 1/(sqrt{3}) and rotates relatively by π/6 [Fig. 4i]. Sublattice 3 displays a scale reduction of 1/2 relative to the primitive lattice, without any relative rotation [Fig. 4j] (as detailed in supplementary Note 2). The Stokes vectors in each unit cell of all the three sublattices rotate from the center ‘up’ state to the ‘down’ state at the boundary, manefesting skyrmion lattices.

Topological decomposition of skyrmion lattice

It has been demonstrated that the topology of skyrmion lattice is constrained by the symmety of optical field, where meron and skyrmion lattices are formed for square and hexagonal symmeties respectively26. This discuss the case for a topological lattice with identical wavevector in the momentum space. However, multiple sets of wavevectors are present in the Stokes skyrmion lattice, leading to the interplay between hierarchical sublattices and the modulation of skyrmion topology.

The sublattice configuration in the Stokes parameter is a result of different composition of wavevectors in synthetic dimensions. For square skyrmion lattices or hexagonal skyrmionium lattices, the period of the sublattices is less than or equal to that of the primary lattice [Figs. 3g–i and 4g–j]. Since the interfering patterns are two-dimensional Bravais lattices, the sublattice can be regularly tessellated by each unit cell of the primary lattice. For example, the sublattice configuration can be arranged by repeating the white frames across the entire plane in Figs. 3g and 4h, demonstrating a periodic compatibility between the primary and sublattices.

The spin states at the boundary of unit cell play a crucial role in the topological decomposition of skyrmion lattice, which is dependent on the symmetry of optical field. For four-fold symmetry, on account of the alternating skyrmion number in the meron sublattices, multiple meron cells are included in a unit cell of the primitive lattice (eg: one positive and one negative merons in sublattice 1 with k = (sqrt{2})kr; two positive and two negative merons in sublattice 2 with k = 2kr). In sublattice 1, the z component of Stokes vector is negative along the boundary, which reaches minima at the vertices, as illustrated in Fig. 3h. Conversely, the Sz distribution exhibits maxima at the vertices and minima at the edge centers for sublattice 2, as illustrated in Fig. 3i. Upon superimposing the two sublattices, the in-plane component of Stokes vectors counteracts and the spin states point along negative z axis at the boundary of each unit cell. While both sub-lattices share maxima value of Sz at the centers, leading to a spin up state at the central of the primary lattice. The synthesis of sublattice configurations results in the square skyrmion lattice, which is abnormal in optical system.

For six-fold symmetry, each sublattice exhibits skyrmion topology with the spin vectors rotating from the central up state to the edge down state, while containing different unit cells based on the wavevector in the Fourier spectrum. In sublattice 1, one skyrmion is included in a unit cell of the primitive lattice. In constrast, three and four skyrmions are contained in one unit cell for sublattice 2 and 3 respectively, leading to the oscillation of Sz between 1 and -1 along the boundary, as shown in Fig. 4i, j. Due to the π/6 rotation of each sublattice relative to the adjacent one in the k-space, the Stokes vectors possess inverse patterns along the cell boudary [Fig. 4i, j], while sharing maxima value of Sz at the centers. Hence the spin vecotrs of synthesis lattice points along the positive direction in both the center and boudary of each unit cell, manifesting a skyrmionium lattice with null skyrmion number. This emphasizes how sublattice interactions shape the composite lattice topology and geometry.

Experimental results

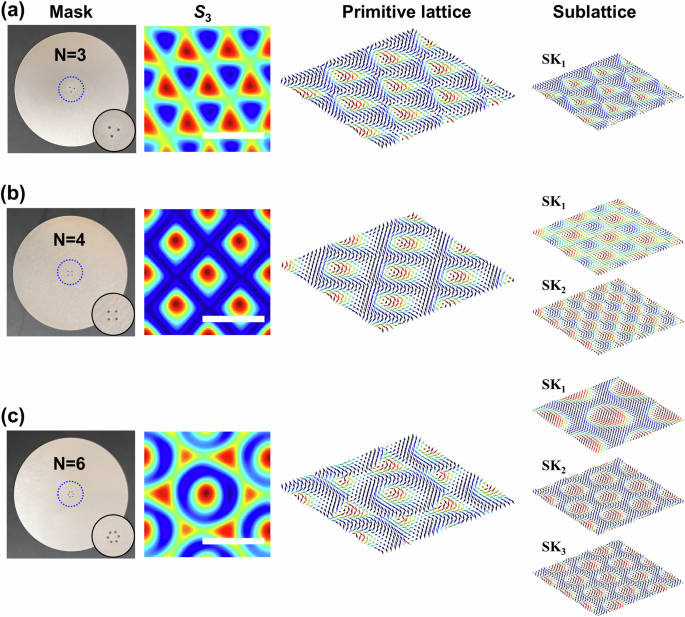

We experimentally demonstrated the skyrmion lattices with 3-fold, 4-fold, and 6-fold rotational symmetries. The details of the experimental setup are provided in Methods section and Supplementary Fig. S6. The measured Stokes distributions and the reconstructed local Stokes vector orientation exhibit a meron lattice for the 3-fold symmetry field (skyrmion number per unit cell: 0.48, alternating between positive and negative values), a skyrmion lattice for the 4-fold symmetry field (0.99), and a skyrmionium lattice for the 6-fold symmetry field (0.11) [columns 3, 4 of Fig. 5a–c], all of which closely align with the simulation results for respective symmetries [cf. Figs. 2c, d, 3c, d and 4c, d]. Higher-order rotational symmetries yield an increased number of sublattice sets. The presence of 3-fold symmetry manifests as a unique ring of lattice points exclusively within the frequency domain. Conversely, 4-fold and 6-fold symmetries exhibit two and three lattice constants in the frequency domain. To extract the sublattices, the inverse fast Fourier-transform (IFFT) is applied to the lattice points in the frequency domain corresponding to (sqrt{2})kr and 2kr for square lattice, and kr, (sqrt{3})kr and 2kr for hexagonal lattice, respectively. This procedure effectively filters out noise to ensure precise results. The reconstructed Stokes distributions exhibit two sets of square meron sublattices for 4-fold symmetry [right column of Fig. 5b]. Sublattice 1 has a skyrmion number of 0.48, and Sublattice 2 has a skyrmion number of 0.47. For 6-fold symmetry, three sets of hexagonal skyrmion sublattices are observed, with skyrmion numbers of 0.97, 0.97, and 0.98 for Sublattices 1, 2, and 3, respectively [right column of Fig. 5c]. These results show good agreement with the simulated results in Fig. 3d, e. The sublattice exhibit different topological properties with respect to the primitive lattice, revealing the complex interaction between Stokes skyrmions. (see Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5 for more experimental results).

The first column to end column of a–c shown the intensity mask in Fourier space, experimental Sz component, the orientation of the normalized Stokes vector of primitive lattice, and sublattices for 3-fold, 4-fold, and 6-fold rotational symmetry, respectively. The scale bar is λr, where λr is the transverse wavelength component.

Discussion

Breaking the rotational symmetry of isolated skyrmions could generated 3-fold triangular meron lattices, 4-fold square skyrmion lattices, and 6-fold hexagonal skyrmionium lattices. In contrast, the other rotational symmetries, such as 5-fold and 7-fold, will form quasicrystals58, which retain rotational symmetry but lack translational symmetry. The proposed generation and decomposition method offers high flexibility for customizing lattice structures. By adjusting the radius of the multi-aperture ring in the mask, the lattice periodicity can be controlled, while the ratio of RCP and LCP determines the radius of skyrmions. Waveplates enable conversion between skyrmion and bimeron topologies, and rotating the mask alters the lattice orientation. These features collectively provide precise control over both the geometric and topological properties of the lattice.

The topological decomposition of skyrmion lattices is specifically effective for primary skyrmion lattices with both rotational and translational symmetries. These lattices have frequency spectra grouped by radii, each corresponding to sublattices with unique periodicities and topological properties, ensuring a clear and unique decomposition scheme for each primary topological lattice. This method is versatile and can be extended to a wide range of skyrmion systems beyond those generated using Stokes vectors. However, it becomes less effective for irregular or non-periodic tiling structures that lack translational symmetry, as the absence of periodicity complicates the identification of sublattices in the frequency domain. Despite this limitation, the approach provides a robust framework for understanding and manipulating structured skyrmion lattices with well-defined symmetries.

Beyond our approach, other techniques for generating skyrmion lattices include conformal cartographic projections59, which map spherical patterns onto planar surfaces, and point light source arrangements that create meron lattices56 each exhibiting unique topological characteristics. Additionally, moiré patterns, formed by overlapping multiple skyrmion lattices60,61,62, provide an avenue for generating more complex skyrmion structures with enhanced features. These alternative methods expand the potential for exploring and applying skyrmion lattices in diverse contexts.

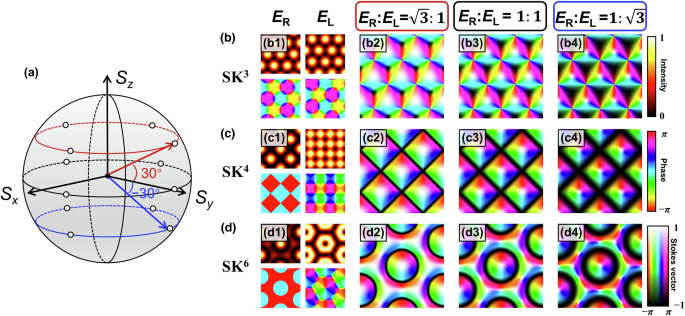

The formation of the skyrmion lattice depends on rotational symmetry-breaking mechanisms of the optical field. On the Poincaré sphere, latitudes θ represent the amplitude ratios between LCP and RCP components with the relation ER/EL = tanθ [Fig. 6a]. The mapping of different points on the Poincaré sphere to corresponding points in the cross-section of the optical field results in the creation of a skyrmion structure34, characterized by a unique arrangement of polarization states, as describe in Eq. (1). The polarization state at the pinhole of the circular ring is determined by the ratio between circular ring of the intensity mask and the beam width. Our findings indicate that the polarization distribution at different latitudes only affects the rotation tendency of spin vectors without changing the topological properties or the unit cell size of the skyrmion, which exclusively depends on the transverse wave vector kr, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 6b–d.

At each latitude, N (N-fold rotational symmetry) polarization states were selected using the intensity mask with pinholes on circular ring. a Poincaré sphere of polarization states. b Triangular meron lattice with 3-fold rotational symmetry. c Square skyrmion lattice with 4-fold rotational symmetry. d Hexagonal skyrmionium lattice with 6-fold rotational symmetry. Figures b1, c1, and d1 shown the amplitude and phase distribution of ER (right-handed circular polarization component) and EL (left-handed circular polarization component). Figures b2, c2, and d2 shown the Stokes topological lattice at 30 degrees north (ER: EL = (sqrt{3}!:1)), Figs. b3, c3, and d3 at the equator (ER: EL = (1!!:1)), and Figs. b4, c4, and d4 at 30 degrees south (ER: EL = (1!!:sqrt{3})). Here, the full three-dimensional normalized Stokes vector (S = [Sx, Sy, Sz]) components were depicted using hue color to map the transverse azimuth from −π to π, and changing brightness to map the z-component from −1 to 1, simultaneously. This method is useful for identifying the geometric structure of the lattice. The polarization states at different latitudes only affects the radius of the skyrmion unit cell (defined as the radius of the geometric shape where Sz = 0 is located) without change the topological properties or the unit cell size of the skyrmion.

The Stokes skyrmion lattice enables various type transformations through the combination of waveplates41. So that the circular ring can also be positioned along other meridians on the Poincaré sphere. For example, by rotating the Poincaré sphere, a meridian can be rotated to the position of equator, such as rotating 90 degrees along Sx. The skyrmion becomes a bimeron40,41, and so does the skyrmion lattice (see Supplementary Fig. S1 for more details). In this case, the latitude only affects the radius of the unit cell in a similar way. In conclusion, any circular ring on the sphere can form a topological structure homeomorphic to a skyrmion. The radius of the circular rings corresponds to the radius of skyrmion unit cell.

Beyond the influence of rotational symmetry, the topological structure demonstrates periodicity with respect to the topological charge of vortex beam, aligning with the rotational symmetry N of the lattice. The topological charge of the incident beam determines the vorticity of the skyrmion lattice, resulting in positive, negative, or even higher-order skyrmions with a vorticity of ±2, which can be decomposed into three second-order skyrmions (see more details in Supplementary Note 3).

The mask design plays a central role in the experiments. The aperture size mainly affects the Gaussian envelope of the lattice, which does not significantly alter the lattice structure itself. The radius of the circular aperture ring, however, has a more direct impact, influencing the lattice periodicity. More importantly, the precision of aperture positioning and size critically affects skyrmion lattice generation. As fabrication errors increase, minor distortions, such as small additional structures at lattice vertices, may arise but generally do not affect the overall topology. However, significant errors lead to severe deformations, compromising both structural integrity and topological consistency. In addition, precision in aperture positioning and size affects the decomposition of skyrmion lattice. Minor inaccuracies introduce minimal distortions, preserving overall integrity. While increasing errors lead to spectrum broadening, vertex distortions, and structural deformations. Severe errors result in significant lattice disruption, including merging and loss of sublattice boundaries (see more details in Supplementary Note 4).

Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrate both theoretically and experimentally the formation of square skyrmion lattices, and hexagonal skyrmionium lattices under 4-fold, 6-fold symmetries in optical system, which is difficult to achieve for magnetic skyrmions. Importantly, we demonstrate the topological synthesis and decomposition of hierarchical skyrmion lattices: the square skyrmion lattices decompose into two sets of square meron lattices, while hexagonal skyrmionium lattices divide into three sets of skyrmion lattices. The number of sublattice sets within the primary lattice is governed by the symmetry. By superimposing different topological lattices with varying lattice constants and specific rotation angles, it is possible to create a skyrmion quasicrystal or topological super-lattice structure analogous to a moiré lattice, enabling precise measurement of tiny displacements or deformations. Stokes skyrmions, with robust topological protection and resilience to perturbations, are well-suited for high-density, error-resistant information storage. Their periodic lattice structures enhance stability and enable advanced encoding schemes based on skyrmion numbers and symmetries, paving the way for optical commination, photonic computing and quantum data storage applications.

Methods

Experimental details

We experimentally demonstrated the skyrmion lattices with 3-fold, 4-fold, and 6-fold rotational symmetries. The experimental setup utilizes one spatial light modulator (SLM) divided into two sections to precisely control the complex amplitude of right and left-handed circular polarization states (RCP and LCP) component of vectorial optical fields, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S6. A He–Ne laser beam (expanded and collimated; horizontal linear polarization; wavelength = 632.8 nm) is employed as the input light source, and the intensity is regulated using a half-wave plate (HWP) and a polarizer. The beam is divided into two parallel beams by the two beam splitters (BS) and a mirror (M). And then, the amplitude and phase of the two beams were modulated by the two sections of SLM. The hologram can be calculated by ({Phi }_{H}=[1-{{{{rm{sinc}}}}}^{-1}({A}_{beam})]cdot ({Phi }_{beam}+{Phi }_{grating}))63. A blazed grating phase is encoded on the SLM to transfer the modulated beam to the first diffraction order. The first diffraction order is filtered by the spatial filter within a 4f-imaging system. The two x-polarized beams were transformed to orthogonal circular polarization RCP and LCP by two quarter-wave plates (QWPs). The superposition of the two beams is achieved using another BS, resulting in the construction of an isolated skyrmion.

To break rotational symmetry, the skyrmionic beam is modulated using intensity masks consisting of three, four, or six evenly spaced pinholes. Each aperture has a radius of 0.15 mm, arranged in a circular ring with a radius of 0.6 mm. The masks are fabricated with a precision of ±20 µm (See Supplementary Fig. S7). The beam is then Fourier-transformed using a Fourier lens. The interference between plane waves results in the formation of skyrmion lattices, which are collected by the CCD. The Stokes distribution is reconstructed by the Stokes polarimetry with a QWP and a polarizer, as described in Eq. (S7) in Supplementary Material.

Responses