Topological dynamics and correspondences in composite exceptional rings

Introduction

Exceptional points (EPs) are non-Hermitian singularities where both eigenvalues and their corresponding eigenstates coalesce, exhibiting intriguing spectral topology distinct from Hermitian nodal structures which feature only coalescing eigenvalues1,2,3,4,5. These unique spectral degeneracies, fundamental to quantum mechanics, have been observed in diverse platforms such as photonic crystals, acoustic cavities, and solid-state spins6,7,8. EPs catalyze many interesting phenomena, including unconventional transmission or reflection9,10,11,12, enhanced sensing13,14,15, and unusual quantum criticality16,17,18,19,20. It should be emphasized that the quasistatic and dynamical encirclement around EPs exhibits intriguing band braiding21,22,23,24,25,26 and chiral mode transfer27,28,29,30,31,32, respectively, which signify the unique consequences of nontrivial EPs topology and provide broad applications for novel generation of quantum devices6,7,8. Besides the unique topology of non-Hermitian systems, EPs also inherit some topological properties of spectral degeneracies in Hermitian systems4,5,6.

Recent advancements have extended beyond isolated second-order EPs (2EPs) to discover exotic structures like high-order EPs33,34,35,36,37,38, exceptional lines39,40,41,42,43, and exceptional nexus44,45 leading to swallowtail catastrophe46, involving more complex coalescing eigenvalues and eigenstates. These exotic exceptional structures enrich the landscape of non-Hermitian physics5,47,48 and provide deeper insights into the quantum mechanisms for open systems49,50,51. Of particular interest, building up a holistic framework governing their non-Hermitian topological phenomena about encirclement process can enhance our understanding of intriguing topological properties and may inspire more applications in non-Hermitian systems52,53,54. However, the encircling outcomes obtained around higher-order and multiple EPs are obscure and lacking in characterization. And the experimental investigations of these higher-order EP geometries remain challenging due to the complexity of constructing non-Hermitian Hamiltonians with intricate degrees of freedom and symmetry constraints in real quantum systems.

In this work, we propose an experimental scheme to realize an intriguing composite exceptional ring (CER), which is an exceptional structure composed of one or more distinct exceptional rings. Specifically, the CER consists of a fixed third-order exceptional ring (TER) and several tunable Weyl exceptional rings (WERs), composed of 3EPs and 2EPs, respectively. By leveraging spin-vector-momentum coupling (SVMC) and spin-tensor-momentum coupling (STMC)55,56,57 this CER exhibits a distinct topological charge characterized by quantized Chern numbers. Traditionally associated with quantized Hall conductance58,59, these Chern numbers play a crucial role in dictating the chirality of boundary states, known as the bulk-boundary correspondence4,5,6. Importantly, we establish a distinctive correspondence linking these “conventional” topological invariants to the non-Hermitian topology of CER, including quasistatic and dynamical encircling results. We demonstrate that nontrivial bands engage in braiding processes during quasistatic encircling, leading to multiperiod spectra. Concurrently, dynamical encirclement triggers complex chiral-mode-switching behaviors, governed by the Chern numbers of system. This intricate behavior not only exemplifies the tunable topological charges of the CER but also extends our understanding of topological phenomena beyond conventional two-band systems. Especially, this correspondence can serve as a guiding principle for analyzing encirclement outcomes, which are invariably obscure and challenging to encapsulate in multiband systems, as well as for designing exceptional structures to attain targeted encirclement results. Furthermore, we show that CER and its encircling dynamics can be experimentally realized with cold atoms. Our work opens new avenues for exploring non-Hermitian topological properties of other complex exceptional structures and for extracting topological invariants in dissipative systems with crystal symmetry60,61,62.

Results

Hamiltonian and symmetries

Building upon recent exploration of triply degenerate points representing a type of quasiparticle excitations without high-energy counterparts and characterized by distinct topological charges55,56,57 (also detailed in the Supplementary Note 1), we begin with the following non-Hermitian Hamiltonian incorporating system dissipation

where ({hat{F}}_{alpha }) represents the spin-1 matrix within a pseudospin-1 framework and kα denotes the effective momentum. The terms ({k}_{alpha }{hat{F}}_{alpha }) and ({u}_{z}{k}_{z}{hat{F}}_{z}^{2}) manifest as SVMC and STMC55,56,57 respectively. Besides the linear dispersion, ({v}_{z}^{{prime} }{k}_{z}^{2}{hat{F}}_{z}) corresponds to the quadratic dispersion component of SVMC, which an be emerged in ultracold pseudospin-1 atomic gases confined within optical lattices56. The term (igamma {hat{F}}_{z}) introduces a non-Hermitian interaction associated with asymmetric dissipation acting on pseudospin states spin-↑ and spin-↓.

The Hamiltonian (1) possesses several intriguing symmetries, that significantly influence the generation of exceptional structures. Firstly, it possesses rotational symmetry around the z-axis, defined by ({hat{{{mathcal{C}}}}}_{z}H({{bf{k}}}){hat{{{mathcal{C}}}}}_{z}^{-1}=H[{{mathcal{R}}}({{{bf{e}}}}_{z},phi ){{bf{k}}}]) with ({hat{{{mathcal{C}}}}}_{z}={e}^{-iphi {hat{F}}_{z}}) and ({{mathcal{R}}}({{{bf{e}}}}_{z},phi )) being element of SO(3) group. This symmetry imposes a spatial arrangement of EPs into rings. Additionally, the Hamiltonian preserves both parity-time (({{mathcal{PT}}})) symmetry63 and pseudochirality symmetry43 in kz = 0 plane. This is articulated by the relations ({e}^{ipi {hat{F}}_{x}}H({k}_{x},{k}_{y},0){e}^{-ipi {hat{F}}_{x}}={H}^{* }({k}_{x},{k}_{y},0)) and ({e}^{ipi {hat{F}}_{z}}H({k}_{x},{k}_{y},0){e}^{-ipi {hat{F}}_{z}}=-{H}^{{dagger} }({k}_{x},{k}_{y},0)). In light of these two symmetries, a significant TER emerges in this plane, characterized by the equation ({k}_{x}^{2}+{k}_{y}^{2}={gamma }^{2}), delineating a phase transition boundary with respect to ({{mathcal{PT}}}) symmetry breaking, as depicted in Fig. 1a. Beyond this plane, the presence of these two symmetries will vanish associated with the absence of 3EP, although WER composed of 2EPs may appear. Furthermore, in the absence of quadratic SVMC interaction (({v}_{z}^{{prime} }=0)), the Hamiltonian also exhibits ({{{mathcal{CM}}}}_{x}) symmetry, expressed as ({e}^{ipi {hat{F}}_{z}}H({k}_{x},{k}_{y},{k}_{z}){e}^{-ipi {hat{F}}_{z}}=-{H}^{* }({k}_{x},-{k}_{y},-{k}_{z})). This symmetry represents a hybridization of particle-hole and mirror symmetries. Under ({{{mathcal{CM}}}}_{x}) symmetry, WERs necessarily appear in symmetric pairs distributed about the kz = 0 plane.

a The typical spectrum in kz = 0 plane. b The exceptional nexus in hx–hz–h2z space (left panel) with the surfaces defined by varying k and its projection (right panel). The parameters used in defining surfaces are indexed by circles, triangles, and squares in c. The structure comprises exceptional lines formed by 2EPs, denoted by green and black lines, which converge at a 3EP marked by a red circle. It is emphasized that only the black lines, which do not lie in hz = 0 plane, can intersect with the surfaces. c The phase diagram with Chern numbers ({{{{mathcal{C}}}}_{-1},{{{mathcal{C}}}}_{0},{{{mathcal{C}}}}_{1}}) and evolution of CER upon inclusion of STMC and SVMC. The pseudospin configurations of each band at the south (north) poles of the integral surface, namely the brown spherical surface, are shown below kS (kN). The typical distribution of exceptional rings has been illustrated for each phase, where red solid (blue dashed) circle indexes the TER (WERs). In all panels, γ = 0.2 is maintained.

Topological composite exceptional ring

To delineate the formation and spatial positioning of WERs, we analyze the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) within the ky = 0 plane, leveraging the rotational ({hat{{{mathcal{C}}}}}_{z}) symmetry. In this configuration, pairs of symmetric EPs extends to form an exceptional ring in 3D space. Specifically, within this setting, the Hamiltonian simplifies to

where ({h}_{x}={k}_{x},{h}_{z}={k}_{z}+{v}_{z}^{{prime} }{k}_{z}^{2}), and h2z = uzkz. The spectrum analysis of H1(k) reveals six two-fold exceptional lines in the hx–hz–h2z parameter space, converging at a 3EP [marked by red circle at coordinates (∣γ∣, 0, 0)], as illustrated in Fig. 1b. This unique configuration is known as an exceptional nexus44. Projecting this nexus onto the hz–h2z plane, results in distinctive mappings of the exceptional lines: two (green lines) project onto the line hz = 0, while the others (black lines) map onto curves approaching the asymptotes h2z = ± hz as ∣h2z∣ tends to infinity.

The parameters hx, hz, and h2z within H1(k) depend on kx and kz, defining a surface in the parameter space. This surface invariably intersects the 3EP at kx = ± γ and kz = 0, correlating with the emergence of TER described in Eq. (1). Specifically, under the purely linear dispersion from SVMC interaction (({u}_{z}^{{prime} }={v}_{z}=0)), the parameter surface remains flat with h2z = 0, intersecting the exceptional nexus solely at the 3EP. After incorporating STMC interaction (uz ≠ 0 and ({v}_{z}^{{prime} }=0)), the initially flat surface inclines with a slope of uz, allowing intersections with the exceptional lines (black lines) at two symmetric points. These intersections herald the emergence of an additional pair of WERs composed of 2EPs. with opposite momenta kz, consistent with the above discussed forementioned symmetries. As strength of STMC increases, these WERs move away from the 3EP towards higher values of ∣kz∣ within the range (0, 1), and eventually vanish when uz > 1, due to the asymptotic relationship h2z = ± hz inherent to these exceptional lines.

When both quadratic SVMC and STMC are incorporated into the Hamiltonian, the parameter surface curves, projecting as a parabola in the hz–h2z plane, corresponding to the location of WERs becoming asymmetric about kz. The number of WERs within ∣kz∣ ∈ (0, 1) remains symmetric about kz = 0 plane for (0 , < , {u}_{z} , < ,1-{v}_{z}^{{prime} }), becoming asymmetric as uz falls within the range (1-{v}_{z}^{{prime} } , < ,{u}_{z} , < ,1+{v}_{z}^{{prime} }). Outside these ranges, the WERs completely disappear when ({u}_{z} , > , 1+{v}_{z}^{{prime} }) or uz = 0. Figure 1b illustrates the outcomes for various values of uz while fixing ({v}_{z}^{{prime} }). Clearly, intersections are confined to the 3EP (3EP and one 2EP) for ({u}_{z} , > , 1+{v}_{z}^{{prime} }) and uz = 0 ((1-{v}_{z}^{{prime} } , < ,{u}_{z} , < ,1+{v}_{z}^{{prime} })) scenarios. The evolution of CER are summarized in Fig. 1c, with detailed discussions available in Supplementary Note 2.

Further analysis reveals that the CER possesses a nontrivial topological charge characterized by Chern number

where Ωn(k) = ∇k × 〈ψn(k)∣i∇k∣ψn(k)〉 denotes the Berry curvature of the nth band. Here the integral surface ({{mathcal{S}}}) encloses CER.

In Fig. 1c, the CER is classified into three distinct topological phases according to its Chern number. Specifically, in the regime dominated by linear SVMC (({u}_{z} , < ,1-{v}_{z}^{{prime} })) and indexed as phase I, the Chern number for CER is given by ({{{mathcal{C}}}}_{n}=-2n), regardless of whether the CER supports paired WERs (uz ≠ 0) or not (uz = 0). Conversely, in the phase II where STMC dominated ({u}_{z} , > , 1+{v}_{z}^{{prime} }), the CER encompasses only one TER and exhibits a Chern number of ({{{mathcal{C}}}}_{n}=-n). In these scenarios, only two bands exhibit nontrivial Chern numbers, akin to the characteristics of a Weyl point and WER. By contrast in the intermediated regime, (1-{v}_{z}^{{prime} } , < ,{u}_{z} , < ,1+{v}_{z}^{{prime} }) the phase III is generated by the interplay between STMC and quadratic SVMC, yielding Chern number configuration of {2, − 1, − 1}. This phase showcases all three nontrivial bands, highlighting complex topological dynamics induced by the combination of STMC and SVMC.

Under the rotational symmetry ({hat{{{mathcal{C}}}}}_{z}), eigenstates along the rotation axis kx = ky = 0 also serve as eigenstates of ({hat{{{mathcal{C}}}}}_{z}), thus preserving their bare spin state. Consequently, the topological charge of the CER can be extracted from the eigenstates at the poles of ({{mathcal{S}}}), as depicted at the top of Fig. 1c. This leads to a simplified expression for the Chern number56,57 (see Method section):

where kS (kN) represents the south (north) pole of the integral surface ({{mathcal{S}}}). Specifically, the E0-band does not occur spin-flipping for phases I and II, while it undergoes a transition from pseudospin-↓ to pseudospin-0 for phases III with three nontrivial bands. This distinctive relationship between spin features and topological charges of the CER leads to diverse topological phenomena during the encircling process, even when the encircling path remains fixed, as discussed subsequently.

Quasistatic encircling process

A defining characteristic of non-Hermitian topology at EPs is the exchange of eigenstates and associated eigenvalues along a quasistatic path encircling the EP, resulting in a nontrivial braiding structure21,22,23,24,25,26,64,65,66. To explore this property, we define a closed path encircling the CER described by

where ϑ varies from 0 to 2π with ϕ and R being constants. It’s worth noting that the choice of ϕ does not affect the spectral behavior due to the rotational symmetry ({hat{{{mathcal{C}}}}}_{z}). For simplicity, we set ϕ = 0, confining the path to the ky = 0 plane, as shown in Fig. 2a. Crucially, the integer period point of this closed path k0 falls within the region of unbroken ({{mathcal{PT}}}) symmetry. This aspect is intricately linked to the topological charge of the CER. In scenarios with a trivial middle band, the branches corresponding to the highest and lowest energies at the initial point [E±1(k0)] intersect, while the third branch returns to its initial state, as illustrated in Fig. 2b and c. In contrast, all branches will swap with each others when CER hosts three nontrivial bands, giving rise to the triple period beyond the two-band non-Hermitian system, as shown in Fig. 2d. Thereby a nontrivial correspondence is established:

where (N({{{mathcal{C}}}}_{n} , ne , 0)) and Tϑ/2π denotes the number of nontrivial bands and the multiple of the spectra period. This relationship inherently reflects a distinctive spin texture associated with different topological charges of the CER. During this quasistatic process, each branch evolves into specific bare spin states at the half period point around kN. Subsequently, during the transition from momentum near kN to momentum near kS, the associated eigenstate predominantly maintains this bare spin state considering (Happrox igamma {hat{F}}_{z}). As the path returns to the ({{mathcal{PT}}}) symmetric point, these bare spin states evolve into eigenstates with real energy. Consequently, band with nontrivial Chern number associated with different bare spin states kN and kS, switch after one period, thereby verifying the correspondence in Eq. (6). We also calculate the Berry phases of the branch over a completed spectra period39. It is found that the two braiding branches shown in Fig. 2c possess nontrivial Berry phases of ± π whereas the leftmost one has a trivial Berry phase. Additionally, all branches depicted in Fig. 2b, d exhibit zero Berry phases. Additional examples and the confirmation of this quasistatic topological property,determined by the Chern number of the CER, are provided in the Supplementary Note 3.

a The typical closed path (black circles) defined in Eq. (5) with radius R = 1. b–d The spectra responses during the quasistatic encircling of CER under different parameter settings. Here, we use vertical gray dashed lines to index points completing encirclements. The parameters are ({v}_{z}^{{prime} }=0.5) and γ = 0.2, while uz = 0 for b, 1.8 for c, and 1 for d. In these cases, the CER includes only one TER (red circle in a) in b and c, and an additional WER (blue circle in a) in d.

Dynamical encircling process

The diverse topological characteristics of CER lead to more intriguing phenomena during dynamic encirclement. Specifically, we dynamically tune the parameter ϑ = ωt in Eq. (5) and the evolution of the state is governed by:

where the subscript denotes clockwise and counterclockwise dynamics associated with ω < 0 and ω > 0, respectively, while the superscript indexes the sign of dissipation γ. Importantly, the Hamiltonian exhibits ({{mathcal{PT}}}) symmetry after periods k(mT) = k0, where T = 2π/∣ω∣ and m is an integer. Particularly, the Hamiltonian approximate reduces to (H[{{bf{k}}}(mT)]approx 2R{hat{F}}_{x}) when dissipation is significantly weaker compared to the coupling strength at the initial time ∣γ/2R∣ ≪ 1.

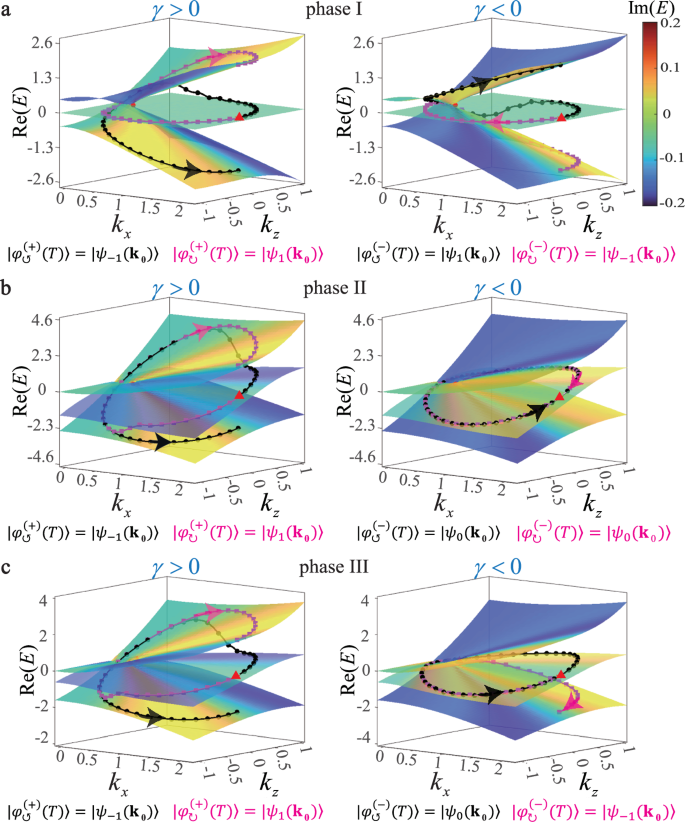

Figure 3 displays the evolution of the state on energy surface during one encircling process, where the outcome is independent of the initial state configuration. As depicted, the encircling process consistently results in chiral behavior that remains invariant with respect to the topological charge of the CER when γ > 0, producing a pair of biorthogonal states. Specifically, under counterclockwise (clockwise) dynamic, the state transitions to the branch with the lowest (highest) real energy: (|{varphi }_{circlearrowleft }^{(+)}(T)rangle =|{psi }_{-1}({{{bf{k}}}}_{0})rangle) [(| {varphi }_{circlearrowright }^{(+)}(T)rangle =| {psi }_{1}({{{bf{k}}}}_{0})rangle)]. Conversely, CERs with different topological charges exhibit distinct encircling dynamics when γ < 0. In phase I, the results for clockwise and counterclockwise dynamics are reversed, as shown in the right panel of Fig. 3a, analogous to the behavior observed in non-Hermitian two-band systems. While the altering of dissipation will produce symmetric outcome for phase II: (|{varphi }_{circlearrowleft }^{(-)}(T)rangle =|{varphi }_{circlearrowright }^{(-)}(T)rangle =|{psi }_{0}({{{bf{k}}}}_{0})rangle), shown in Fig. 3b. Despite both scenarios involving one TER, their distinct topological charges result in different encircling dynamical behaviors. Moreover, in phase III, where the CER hosts all nontrivial bands, unique chiral dynamics are evidently illustrated by (|{varphi }_{circlearrowleft }^{(-)}(T)rangle =|{psi }_{0}({{{bf{k}}}}_{0})rangle) and (| {varphi }_{circlearrowright }^{(-)}(T)rangle =|{psi }_{-1}({{{bf{k}}}}_{0})rangle), contrasting with other scenarios, as shown in Fig. 3c.

The expectation energy during counterclockwise (clockwise) encirclement process is depicted by black lines with circles (magenta lines with squares). The energy of initial state is marked with a red triangle. Parameters are set to ({v}_{z}^{{prime} }=0.5,| gamma | =0.2), and ∣ω∣ = 0.02π for all panels. The specific value of uz is uz = 0 for a, 1.8 for b, and 1 for c, matching those in Fig. 1b.

The dynamical results of encircling processes around CER are governed by the Chern number, as demonstrated with additional examples in the Supplementary Note 3 and explained by Eq. (4). Notably, the evolution of the system is prominently influenced by the dissipation term around the midpoint of the cycle (t = T/2), causing the states to converge towards the bare spin state (|uparrow rangle) ((|downarrow rangle)) for γ > 0 (γ < 0). Consequently, the momentum evolves from near kS (kN) to k0 in the counterclockwise (clockwise) encirclement process, corresponding to the state evolving adiabatically. Thus, the results of encircling are determined by which branch aligns with (|uparrow rangle) ((|downarrow rangle)) at kS and kN in the counterclockwise and clockwise encirclement processes under positive (negative) dissipation, respectively. Considering the relationship given in Eq. (4), the correspondence between dynamic encircling process and Chern number is further established by the equation

with r↻ = − r↺ = 1. This pivotal relationship provides a systematic approach to analyzing state transitions in different exceptional structures and extracting topological invariants from dissipative topological phases. Actually, this dynamical correspondence is established via the bridge that connects topological invariants and symmetry indicators at higher symmetric momenta. Thus, this approach can be applied to topological phases defined by other topological invariants as well. Given that a large number of topological crystalline phases have been discovered through symmetry-based indicators60,61,62, it should be noted that some of these phases cannot be characterized by conventional topological invariants and even lack the bulk-boundary correspondence. Our results can be extended to these systems and established dynamical correspondence will be conducive to extracting their topological features, which can be achieved by introducing suitable dissipation and investigating the dynamical process.

Experimental scheme with cold atomic gases

The observed CER with its dynamical encirclement can be realized for ultracold gases trapped in 2D square optical lattice. The experimental setup involves three hyperfine states in the spin-1 ground manifold, manipulated by Raman-assisted spin-orbit couplings. Additionally, the dissipation for (|uparrow rangle) and (|downarrow rangle) states can be generated by using a resonant optical beam18. To proceed further, the lattice Hamiltonian in momentum space under periodic boundary conditions is given by (further details can be found in Method section):

where ({d}_{x}({{bf{k}}})=sin {k}_{x},{d}_{y}({{bf{k}}})=sin {k}_{y},{d}_{z}({{bf{k}}})=delta +igamma ,{d}_{z}^{{prime} }({{bf{k}}})={delta }_{2}-4{t}_{u}cos {k}_{x}-4{t}_{u}cos {k}_{y}), and (epsilon ({{bf{k}}})=2{t}_{u}cos {k}_{x}+2{t}_{u}cos {k}_{y}) with tu being the strength of spin-independent hopping. And δ and δ2 are two-photon detunings dependent on a tunable parameter kz: (delta ={k}_{z}+{v}_{z}^{{prime} }{k}_{z}^{2}) and δ2 = uzkz + 8tu. The effective Hamiltonian near k = 0 corresponds to the formulation presented in Eq. (1). The square geometry is taken for this lattice system, where non-Hermitian skin effect can be prevented67,68 due to the four-fold rotation symmetry ({e}^{-ipi {hat{F}}_{z}/2}{H}_{0}({k}_{x},{k}_{y}){e}^{ipi {hat{F}}_{z}/2}={H}_{0}(-{k}_{y},{k}_{x})). Real and imaginary components of the spectrum can be observed through frequency and decay rate of Rabi oscillations in cold atom system18, thereby enabling the detection of CER.

To facilitate the dynamical encircling process, the incorporation of on-site spin-flipping dynamics is crucial, which can be described by the Hamiltonian:

where tx denotes the strength of on-site spin-flipping, adjusted to control the central momentum kx of CER. For constructing the dynamical encircling process, we modulate ({t}_{x}=R[1+cos (omega t)]) and adjust ({k}_{z}=Rsin (omega t)). Here, we assume a deep lattice where the nearest-neighbor tunneling is negligible (tu = 0). The initial state is prepared as a zero-momentum Gaussian wavepacket in real space with a width σ, and in spin space as the state (|0rangle). To monitor the dynamical process, an observable related to the spin component of zero momentum state (|v(t)rangle =langle {{bf{k}}}=0| varphi (t)rangle) is introduced:

This observable can be directly measured using spin-resolved time-of-flight images in cold atom experiments69. After completing one encircling period, (langle {hat{F}}_{x}rangle) is expected to approximate values close to − 1, 0, or 1, as shown in Fig. 4, reflecting the characteristics of the continuous Hamiltonian dynamics depicted in Fig. 3, considering (H({{{bf{k}}}}_{0})approx 2R{hat{F}}_{x}). These configurations not only highlight the versatility of the experimental setup but also deepen the understanding of dynamical topological phenomena in non-Hermitian systems.

The observable (langle {hat{F}}_{x}rangle) defined in Eq. (11) throughout the dynamic encirclement of CERs with distinct topological charges. The initial state is a Guassian wavepacket centered at zero momentum with a width of σ = 4. Parameters are fixed at ({v}_{z}^{{prime} }=0.5,| gamma | =0.2,| omega | =0.02pi) and R = 1 for all panels. Specific values of uz are 0 for a, 1.8 for b, and 1 for c. Results for different signs of γ and ω are distinguished by different line and symbol colors (red circle, black square, orange triangle, and blue diamond), as indicated in the inset of a.

Conclusion

We have explored an intriguing exceptional structure named as CER, consisting of a TER and a variable ensemble of WERs based on recent research into exotic band degeneracy points associated with unconventional quasiparticle excitations. By manipulating the interplay between STMC and quadratic SVMC, this CER exhibits a range of topological charges, characterized by Chern number. Importantly, we have established the clear link between these Chern numbers and the topological properties embed during the encirclement process. The emergence of the CER, driven by STMC and quadratic SVMC, enables intricate band braiding and state transitions that transcend conventional two-band systems. This relationship underscores the profound link between conventional topological invariants and dynamic quantum phenomena unique to non-Hermitian systems, enhancing our comprehension of topological physics in non-Hermitian systems. Specifically, one can utilize the topological charge to analyze and even design the encirclement physics of other exceptional structures. Conversely, it is also possible to measure the topological charge through encirclement outcomes. The interplay between this dynamical correspondence and other characteristics of topological phases might give rise to more fascinating phenomena, which we will explore in the future. Furthermore, we have proposed achievable experimental setups utilizing cold atoms in optical lattices to realize the CER. The insights gained from our study may pave the way for further exploration of unique exceptional structures and hold promise for diverse applications in designing quantum devices based on non-Hermitian topologies.

Methods

Chern numbers and spin textures

In this section we discuss the relationship between spin textures and the Chern number of CER. We choose the integration surface ({{mathcal{S}}}) in the Eq. (3) as a spherical surface enclosing CER, centered at the origin with polar (azimuth) angle θ (ϕ). Due to the rotation symmetry, Hamiltonian H from Eq. (1) satisfies (H(theta ,phi )={e}^{-iphi {hat{F}}_{z}}H(theta ,0){e}^{iphi {hat{F}}_{z}}), and then corresponding eigenstates of nth band can be expressed as:

where (|{psi }_{n}(theta ,0)rangle) is a smooth and single valued function of the polar angle θ. The Berry connection is then given by:

Notifying (|{psi }_{n}(theta ,0)rangle) is independent of ϕ, the Berry curvature will be:

As a result, the Chern number of CER is expressed as:

which corresponds precisely to Eq. (4).

It is noteworthy that Eq. (15) holds true for both Hermitian56,57 and non-Hermitian system. Previous studies have demonstrate that the Chern number of triply degenerate point can be revealed by measuring spin texture along the rotation axis kx = ky = 0, where it equals the spin-flipping behavior at the origin (the location of triply degenerate point). In the Hermitian system, the band index can be reliably determined based on their local energies. In contrast, the band index is determined by the ({{mathcal{PT}}}) symmetric momenta k0 in present non-Hermitian system.

Derivation of the lattice Hamiltonian for cold atoms

In this section, we derive the lattice Hamiltonian for cold atoms in detail.

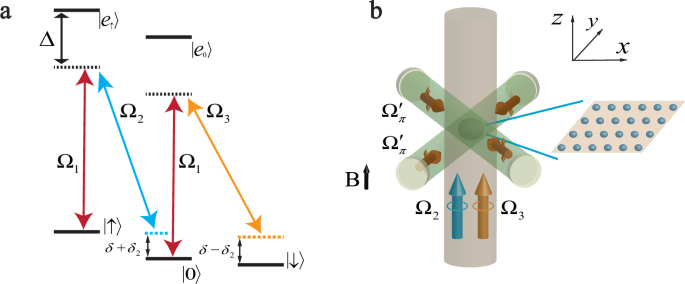

As discussed in above and shown in Fig. 5, we consider an ultracold gas subjected to a bias magnetic along z axis and trapped in a square optical lattice ({{{mathcal{U}}}}_{{{rm{ol}}}}({{bf{r}}})=-{U}_{ol}[{cos }^{2}({k}_{L}x)+{cos }^{2}({k}_{L}y)]). We focus on five relevant magnetic Zeeman sublevels, including three ground states and two electronic excited states, as shown in Fig. 5a. The atomic transition frequency between the ground and excited states is denoted by ωa. Under the influence of the magnetic field, the linear and quadratic Zeeman shifts for the ground (excited) states are ωZ and ωq (({omega }_{Z}^{{prime} }) and ({omega }_{q}^{{prime} })), respectively.

a Involved five sublevels. b Illustration of laser configurations and optical lattices. The atoms are trapped in a 2D optical lattice. The red lasers represent π-polarized standing-wave lasers that couple the state (|sigma rangle) to (|{e}_{sigma }rangle) with σ = ↑, 0, while the blue (orange) laser represents a σ-polarized standing-wave laser along z direction that couples (|0rangle leftrightarrow |{e}_{uparrow }rangle) ((|{e}_{0}rangle leftrightarrow |downarrow rangle)).

To manipulate the atoms, we introduce two π-polarized standing-wave lasers, represented by the red lines in Fig. 5, which couple the state (|sigma rangle) to (|{e}_{sigma }rangle) with σ = ↑, 0. The detuning between the atomic and laser frequencies is Δ = ωa − ωL with ωL being the laser frequency. The Rabi frequencies of two standing-wave lasers are ({Omega }_{pi }^{{prime} }sin ({k}_{L}x-{k}_{L}y)) and (i{Omega }_{pi }^{{prime} }sin ({k}_{L}x+{k}_{L}y)), respectively, giving rise to the total Rabi frequency ({Omega }_{1}({{bf{r}}})={Omega }_{pi }[sin ({k}_{L}x)cos ({k}_{L}y)+icos ({k}_{L}x)sin ({k}_{L}y)]) with ({Omega }_{pi }=sqrt{2}{e}^{ipi /4}{Omega }_{pi }^{{prime} }). Additionally, a σ-polarized standing-wave laser along z direction with Rabi frequency Ωσ couples (|0rangle leftrightarrow |{e}_{uparrow }rangle) ((|{e}_{0}rangle leftrightarrow |downarrow rangle)) with frequency ωL + ΔωL (({omega }_{L}-Delta {omega }_{L}^{{prime} })), as indicated by the blue (orange) line in Fig. 5. Moreover, additional radio frequency pulses generate effective dissipation for (|uparrow rangle) and (|downarrow rangle) states.

When the atom-light detuning Δ is large, we can adiabatically eliminate the excited states to derive the effective Hamiltonian within the ground state manifold56:

where ({M}_{x}(r)=Omega sin ({k}_{L}x)cos ({k}_{L}y)), and ({M}_{y}(r)=Omega cos ({k}_{L}x)sin ({k}_{L}y)) with (Omega =-sqrt{2}{Omega }_{pi }{Omega }_{sigma }/Delta). Here (delta ={omega }_{z}+frac{Delta {omega }_{L}^{{prime} }-Delta {omega }_{L}}{2}+frac{| {omega }_{sigma }{| }^{2}}{2Delta }) and ({delta }_{2}=-{omega }_{q}-frac{Delta {omega }_{L}^{{prime} }+Delta {omega }_{L}}{2}-frac{3| {omega }_{sigma }{| }^{2}}{2Delta }) act as tunable effective Zeeman fields, and γ represents the strength of dissipation.

Incorporating nearest-neighbor hopping between lowest s orbits, we obtain the lattice Hamiltonian

where ({hat{psi }}_{{{bf{j}}}}={[{hat{a}}_{{{bf{j}}},uparrow },{hat{a}}_{{{bf{j}}},0},{hat{a}}_{{{bf{j}}},downarrow }]}^{T}) with ({hat{a}}_{{{bf{j}}},sigma }) is the annihilation operator for the σ component at site j, and ({hat{n}}_{{{bf{j}}},sigma }={hat{a}}_{{{bf{j}}},sigma }^{{dagger} }{hat{a}}_{{{bf{j}}},sigma }). tu is the spin-independent hopping and t0 is the strength of spin-flipping hopping.

To further process the system, a gauge transformation, ({hat{a}}_{{{bf{j}}},0}to {(-1)}^{(m+n)}i{hat{a}}_{{{bf{j}}},0}), has been implemented56. Upon Fourier transformation, the Hamiltonian in momentum space takes the form as (the lattice constant is taken as unit a ≡ 1/kL ≡ 1)

where the coefficients are defined as follows: ({d}_{x}({{bf{k}}})=2{t}_{0}sin {k}_{x},{d}_{y}({{bf{k}}})=2{t}_{0}sin {k}_{y},{d}_{z}({{bf{k}}})=delta +igamma ,{d}_{z}^{{prime} }({{bf{k}}})={delta }_{2}-4{t}_{u}cos {k}_{x}-4{t}_{u}cos {k}_{y}), and (epsilon ({{bf{k}}})=2{t}_{u}cos {k}_{x}+2{t}_{u}cos {k}_{y}). Additionally, the parameters δ and δ2 act analogously to effective Zeeman fields. Setting (delta =2{t}_{0}{k}_{z}+4{v}_{z}^{{prime} }{t}_{0}^{2}{k}_{z}^{2}) and δ2 = 2uzt0kz + 8tu, which vary with the parameter kz, the effective Hamiltonian expanded around kx = ky = 0 is given by:

Upon setting 2t0 as the energy unit (2t0 ≡ 1), HCER corresponds to the Hamiltonian of CER in Eq. (1).

As discussed in above, on-site spin-flipping is introduced to realize the dynamic encircling process around CER. This effect is achieved by introducing two π-polarized standing-wave lasers that couple (|sigma rangle) to (|{e}_{sigma }rangle) with σ = ↑, 0 at the frequency ωL, as the red one in Fig. 5. The Rabi frequencies of these lasers are ({Omega }_{pi }^{{primeprime} }cos ({k}_{L}x-{k}_{L}y)) and ({Omega }_{pi }^{{primeprime} }cos ({k}_{L}x+{k}_{L}y)), yielding the total Rabi frequency of (2{Omega }_{pi }^{{primeprime} }cos ({k}_{L}x)cos ({k}_{L}y)). As a result, the momentum space Hamiltonian is modified to

whose momentum representation is detailed in Eq. (10). By adjusting tx, δ, and δ2, the dynamical encircling process can be realized.

We assume the lattice depth is sufficiently deep to suppress tunneling (tu = 0). Other parameters are tuned as

during the dynamical process. The initial state is prepared as a Gaussian wavepacket:

where ({{mathcal{N}}}) is the normalization factor, m (n) is the lattice index along x (y) direction with m0 (n0) denoting the center position of wavepacket, and σ is the width of Gaussian wavepacket. This setup allows for the simulation of the dynamical encircling process. Future investigations will explore additional topological features, such as boundary states within this lattice model.

Responses