Tough polymer gels reinforced by strain-induced crystallization

Introduction

Polymer gels are soft materials comprising a polymer network and a solvent. Hydrogels swollen with water have high biocompatibility; thus, they are candidates for the implantation of biomedical materials, such as artificial vessels, ligaments, and tendons [1]. Ion gels containing salt as a solvent exhibit ion conductivity and can be used in applications involving soft electronic devices, such as soft actuators/sensors and flexible batteries [2]. However, conventional polymer gels are mechanically fragile [3], which limits their application.

Since 2000, the mechanical toughness of polymer gels has been significantly improved using sophisticated network architectures [4,5,6]. Tough polymer gels are classified into two groups: (i) dissipative tough gels with breakable bonds and (ii) highly deformable homogeneous gels. Dissipative tough gels have breakable weak cross-links between the polymers, such as ionic interactions, hydrogen bonds, coordinate bonds, and hydrophobic interactions [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. When dissipative gels are deformed, the weak cross-links are broken to dissipate energy, leading to their high mechanical toughness [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. The fracture energy of dissipative tough gels reaches 1000 J/m2, which is approximately 100 times greater than that of conventional gels (approximately 10 J/m2). The mechanical toughness can also be improved by homogenizing the network structure [12,13,14]. Conventional gels have an inhomogeneous network structure with a distribution of strand lengths between the cross-linking points, causing stress concentration on the short strands under deformation. Stress-concentrated strands are highly stretched and ruptured, resulting in the brittle fracture of conventional polymer gels. To reduce the stress concentration, Ito et al. fabricated slide-ring (SR) gels in which the polymer chains were cross-linked by ring molecules [12, 13]. When the SR gels were deformed, the ring cross-links slid along the polymer chains to homogenize the chain deformation and tension. Sakai et al. developed a homogeneous polymer gel, called tetra-polyethylene glycol (Tetra-PEG) gel, by end-crosslinking tetrabranched PEG macromers [14]. SR and Tetra-PEG gels could be stretched to high strains without any chain rupture and mechanical hysteresis [13, 15]. However, although the toughness of SR and Tetra-PEG gels is greater than those of conventional polymer gels, their fracture energy ranges from 10 to 50 J/m2 [16, 17]; these values are lower than those of dissipative tough gels. Once highly stretched polymer chains rupture in homogenous gels, chain breakage causes macroscopic fracture [18].

In this work, we introduce our recent studies on a significant improvement in the mechanical toughness of homogeneous polymer gels via strain-induced crystallization (SIC) [19,20,21,22].

Although SIC is a well-known toughening mechanism in natural rubbers [23], to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies on the SIC of amorphous polymer gels have been reported. We found that SIC occurred for the SR and Tri-/Tetra-PEG gels with sufficient polymer concentrations; this drastically increased their crack propagation resistance. The strain-induced crystals disappeared immediately after strain reduction. The reversible formation/dissolution of the polymer crystals yielded elastic mechanical responses with minimal hysteresis under cyclic stretching. Recently, tough and elastic polymer gels have emerged in the field of polymer gel science [24,25,26].

Strain-induced crystallization of slide-ring hydro gels

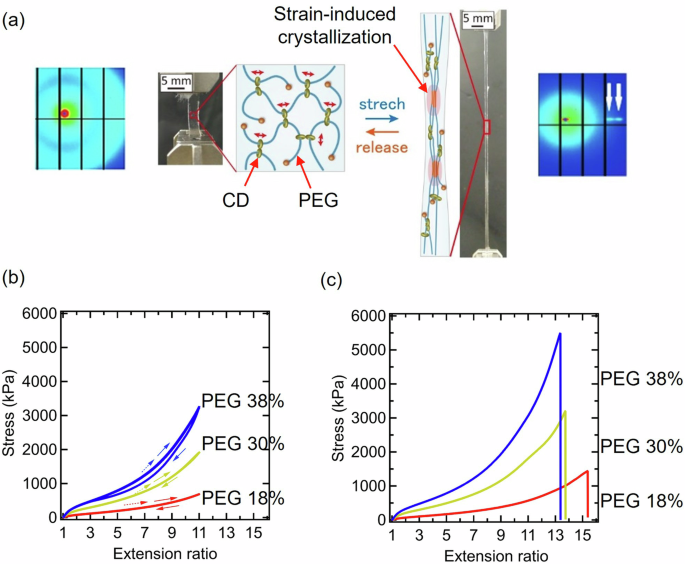

We discovered reversible SIC in SR hydrogels [17]. SR gels are prepared by cross-linking the ring molecules of polyrotaxanes, in which cyclodextrins (CDs) are threaded onto polyethylene glycol (PEG). SIC occurs in the SR gels under the following conditions: (i) low CD coverages on PEG, (ii) high PEG concentrations, and (iii) high PEG molecular weights [19]. In previous studies, the CD coverage of the conventional SR gels was approximately 25%, and they did not exhibit SIC [12, 13]. In conventional SR gels, the presence of uncrosslinked CDs on PEG suppresses the SIC of PEG. Recently, we successfully synthesized low-coverage polyrotaxane in high yields [16, 27]. By using a polyrotaxane with 2% CD coverage and 35 k/mol of PEG molecular weight, we fabricated SR gels with almost no uncrosslinked CDs and on PEG. While SR gels with PEG concentrations lower than 13% do not undergo SIC and have fracture energies lower than 50 J/m2 [16], SIC occurs in the SR gels with PEG concentrations higher than 18% [19]. When we stretch the SR gels with SIC, the polymer chains are uniformly stretched and aligned in the stretching direction, followed by crystallization of planar zigzag PEG at high strains, as shown in Fig. 1a. SIC was confirmed from diffraction spots in wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) patterns (Fig. 1(a)). The diffraction spots corresponding to the strain-induced crystals disappeared immediately when the applied strain decreased. The reversible SIC resulted in elastic mechanical responses with minimal hysteresis under repeated stretching (Fig. 1b). Owing to SIC, the rupture stress and strain of the SR gels were 1–5 MPa and 1200–1400%, respectively (Fig. 1c). The fracture energy of the SR gels ranged from 2200 to 3600 J/m2; these values were comparable with those of the dissipative tough gels.

a Reversible strain-induced crystallization of the SR hydrogels, (b) loading‒unloading stress‒extension ratio curves and (c) stress‒extension ratio curves until fracture of the SR hydrogels with different PEG concentrations. Reproduced from Ref. [19] with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science

Strain-induced crystallization of slide-ring ion gels

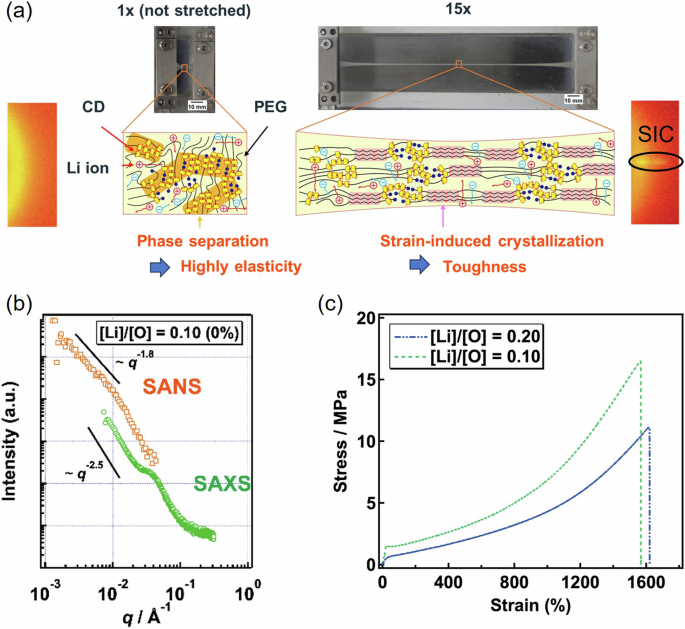

SIC can occur not only in hydrogels but also in ionic gels. We successfully fabricated tough and stiff SR ion gels containing a lithium salt using SIC of PEG and phase separation of CDs (Fig. 2a) [20]. Ion gels containing Li salts have been used as separator membranes in flexible batteries. Electrolyte membranes require high stiffness (Young’s modulus) and toughness (fracture energy). High stiffness (Young’s modulus >10 MPa) is required to prevent short circuits due to Li metal dendrite growth in the electrode during charge‒discharge [28]. High toughness is desirable for suppressing crack propagation under repeated deformation of flexible batteries. However, for conventional polymer gel electrolytes, a trade-off between toughness and stiffness exists. We have overcome this trade-off by combining the phase separation of CDs and the SIC of PEG.

a Strain-induced crystallization and phase separation of tough and stiff SR ion gels, (b) SANS and SAXS profiles of an SR ion gel, and (c) stress‒strain curves until fracture of the SR ion gels. Reproduced from Ref. [20] with permission from the American Association for the Advancement of Science

In the SR ion gel, the CDs do not dissolve in the Li salt and form a continuous hard domain, yielding a high Young’s modulus (>10 MPa). The phase-separated structure was observed via small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). Figure 2b shows the SANS and SAXS profiles of the SR ion gel. A broad peak at 3.0 × 10−2 Å−1 corresponds to a correlation length of 20 nm, which is consistent with the distance between the aggregates of CDs observed via atomic force microscopy (AFM). The power law behavior I(q) = q−2.5 in the lower q regime indicates that the CD aggregates form a 3D network structure. Furthermore, the SR ion gels exhibit SIC of PEG, as confirmed by WAXS (Fig. 2a), resulting in their high stretchability (Fig. 2c) and high crack propagation resistance (fracture energy: 33 kJ/m2).

Strain-induced crystallization of Tri-PEG and Tetra-PEG gels

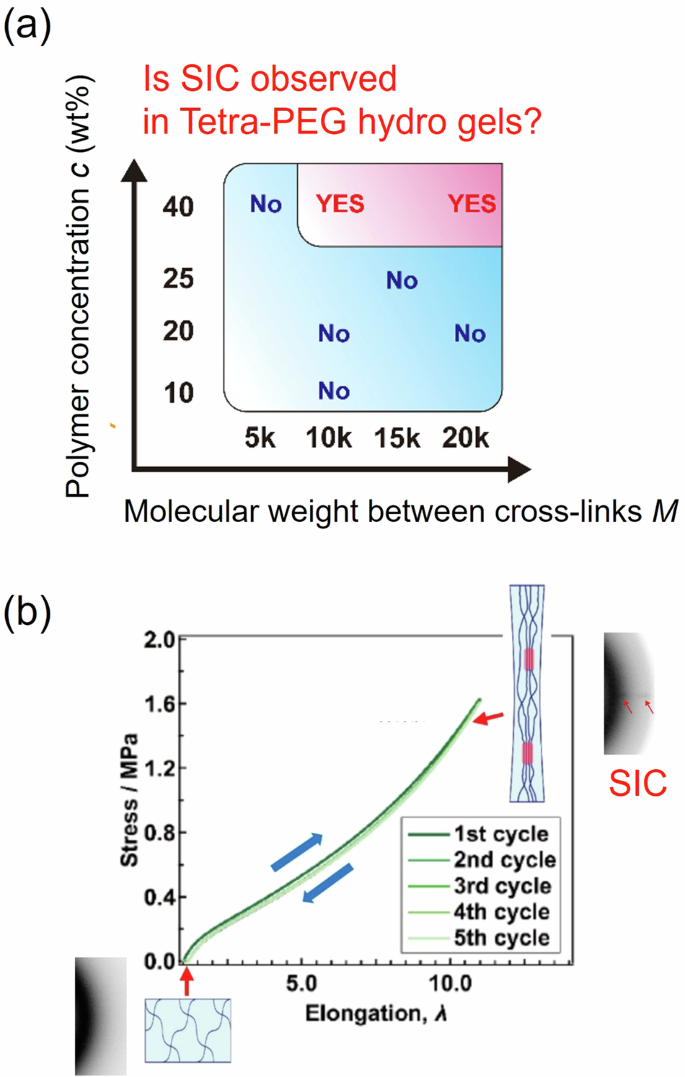

In addition to SR gels, homogeneous polymer gels with covalent cross-links exhibit SIC under appropriate conditions [21, 22]. In covalently cross-linked homogeneous gels, SIC occurs for smaller branch numbers, higher polymer concentrations, and longer strand lengths between the cross-linking points [21, 22]. For Tetra-PEG hydrogels, SIC is observed when the PEG concentration c ≥ 40% and the strand molecular weight between the branching points M ≥ 10 k g/mol (Fig. 3a) [22]. Tetra-PEG gels with SIC exhibit high mechanical toughness (fracture energy: 650 J/m2) and elastic mechanical responses originating from reversible SIC, as observed by WAXS (Fig. 3b) [22]. Furthermore, Tri-PEG gels, formed from tri-branched PEG macromers, show SIC at a relatively lower polymer concentration than Tetra-PEG gels [21].

a Phase diagram of the PEG concentration c and PEG molecular weight between the cross-links M where SIC occurs for Tetra-PEG hydrogels. b Loading‒unloading stress‒extension ratio curves of Tetra-PEG hydrogels showing reversible SIC. Reprinted from Ref. [22] with permission from the American Chemical Society

Conclusions

In this work, we provide an overview of our recent progress in toughening homogeneous polymer gels, SR and Tri-/Tetra-PEG gels, using SIC. Because polymer chains in polymer gels are diluted with solvent, SIC is more unlikely to occur in polymer gels than in rubbers containing no solvent. Our recent studies revealed that homogeneous polymer gels have the advantage of uniformly aligning polymer strands in the stretching direction, resulting in an efficient SIC. SIC occurs in homogeneous polymer gels, such as SR gels and covalently cross-linked Tri-/Tetra-PEG gels, with sufficiently high polymer concentrations and large molecular weights of polymer chains.

Because strain-induced polymer crystals form and dissolve rapidly under cyclic stretching, tough and elastic polymer gels with little mechanical hysteresis can be fabricated due to SIC; these gels are difficult to attain using the concept of dissipative tough gels containing breakable bonds. Tough and elastic hydrogels and ion gels can be applied to biomedical materials and soft electronic devices that need constant mechanical responses under repeated deformation.

Responses