Towards an interpretable deep learning model of cancer

Introduction

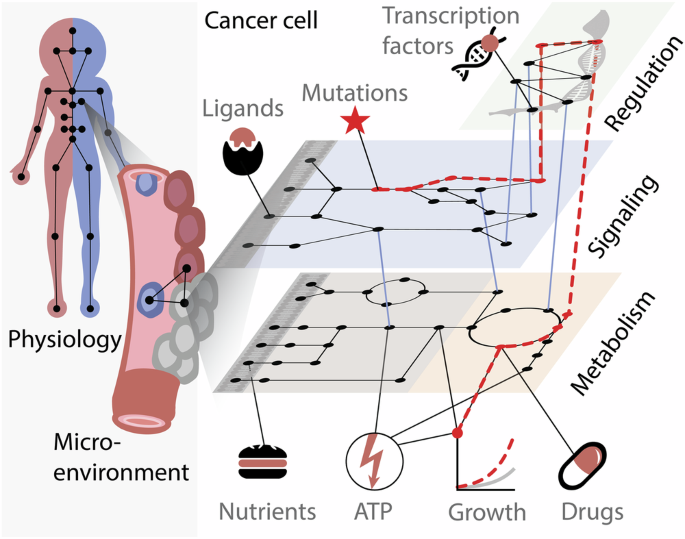

Cancer is a diverse neoplastic disease, where mutations and other alterations drive phenotypes such as sustained cellular proliferation, and evasion of the immune system1. Safe and effective cancer treatments could in principle be attained by targeting these specific deviations, i.e., precision medicine2. However, in practice, this is challenging because cellular processes are highly interconnected and furthermore depend on the microenvironment (Fig. 1). This complexity hampers our ability to establish causal relations between genetic alterations and disease phenotypes, such as which mutations are driving the disease and which are passengers3. It has been found that inhibiting cancer-specific signaling proteins can be highly effective4, but such treatments can also be thwarted by negative feedback loops, e.g., an ERK-dependent feedback loop that attenuates the effects of RAF inhibition5. Even if a treatment is successful at first, there may emerge cells that are resistant to treatment due to cellular heterogeneity, which may originate from both genomic and epigenetic differences6. Furthermore, cancer cells interact with other cells in their microenvironment, which expands their signaling repertoire7. Overall, this interplay between mutations, drugs, resistance mechanisms, feedback loops, and environmental factors, gives rise to a combinatorial number of possible causes, which can be challenging to investigate experimentally. A computation approach would therefore be advantageous.

Effects of a mutation in a signaling protein can propagate through gene regulation, and metabolism, to affect cellular growth.

Living cells are dynamical systems that depend on biochemical interactions between a vast number of molecules, which are governed by physico-chemical laws of kinetics and transport. Such systems can be described using mathematical models, and for this, models based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs) have commonly been used. They can be applied to model interactions between proteins and metabolites, enable predictions of disease-associated molecules, and provide mechanistic explanations of perturbations8,9,10,11. In principle, if all molecular relations were known and stochastic effects were disregarded, the activity of a cell could be derived from its initial condition, i.e., bottom-up modeling12. However, this remains severely daunting for both practical and theoretical reasons13, and an appealing alternative is to fit model parameters to systems-level data, i.e., top-down modeling.

Machine learning (ML) and specifically deep learning (DL) models are now becoming broadly employed in biology and medicine. These algorithms are trained, i.e., parameterized, on data to make rapid predictions that generalize to unseen conditions. Together with large-scale high throughput screening datasets14,15,16, these models have been successfully used in a wide variety of tasks17, including predicting drug synergy18, response to therapy19, survival probabilities20, disease outcomes21, and for cancer histology22. Some models include molecular structure in their description of the input, which allows them to extrapolate their predictions to untested molecules17,23. Many of these models predict phenotypes of interest without accounting for the underlying mechanisms, and they have therefore been criticized for their lack of biological interpretability24. Recently, prior biological knowledge has been integrated with the ML models, e.g., in the form of molecular networks, thereby making them more structured and interpretable, and has shown promising results at both the patient- and cellular level25,26,27,28.

The utility of network-based approaches for studying cancer has long been appreciated. These have been used to map the cell’s functional organization29, for causal integration and mechanistic hypotheses-generation on cancer data30, and to characterize the response to drug therapies and their mechanism of action31. A plethora of network-centric tools has been created for interrogating the biology of diseases and the mechanism of action of therapeutic solutions32. For example, in Cytoscape researchers may integrate large molecular networks and omics data, to perform network statistics and visualization in a fast and simple way33. Some approaches, such as CausalR34 CARNIVAL35, and COSMOS30, utilize omics data and prior knowledge to propose causal networks that underlay the observed condition. Additionally, some approaches simultaneously infer gene regulatory networks from single-cell RNA sequencing data and use them to perform in silico perturbations, thus interrogating the potential effect of the perturbation of specific molecular species36,37. However, most network-based approaches are primarily descriptive; i.e., they are not constructed to make quantitative predictions about unseen conditions, such as combinations of mutations that have not previously been observed. This may therefore require manual interpretation. Furthermore, they do not generally encode the structure of the molecules that induce the observed biological effect, and therefore cannot directly predict the effects of previously untested molecules.

Because cellular processes are highly interconnected in cancer, system-level models are required to predict the effects of mutations and other alterations. In this perspective, we discuss the feasibility of constructing such models in light of recent progress in DL algorithms, and data acquisition methods, along with the accumulated prior knowledge of molecular networks. We also explore potential applications if such a model is successfully implemented.

Predictive deep learning models

ML, and in particular artificial neural networks (ANNs) facilitate the construction of large-scale predictive models. ANNs approximate unknown, complex functions through a sequence of linear matrix operations and non-linear transformations, with layers of latent variables between them. The models are referred to as ‘deep’ if multiple layers are used. These models can contain millions of parameters and can rapidly be fitted to paired samples of input- and output data using automatic differentiation. The flexibility and scale of DL make it a promising candidate for fitting models of complex and heterogeneous molecular data. For cancer specifically, DL has been used to predict response to therapy19, and tumor phenotypes after perturbations with high performance38, and other ML models have been used to predict patient response using transfer learning approaches from pre-clinical models39.

However, while DL models excel at predictions, their relation to the underlying mechanisms that they approximate is often opaque, i.e., the black box problem25. It has therefore been proposed that more interpretable DL models should be used for biological systems, and explainable AI has indeed gained a lot of interest over the last years40,41. For example, Keyl et al. used an interpretation method termed layer-wise relevance propagation40, coupled with an ANN model for predicting protein interaction networks from proteomic data for individual patients42. Laurie and Lu developed a DL architecture for survival prediction, whose components capture specific aspects of tumor dynamics43.

We reason that, while purely predictive models can be useful for many tasks, such as prioritizing perturbations for further experimental validation, the development of safe and effective therapeutics, should be rooted in a purposeful process. Particularly, they should be designed to affect specific targets, with known mechanisms of action, and well-characterized dynamics. This may be achieved by a model of the human cell. According to a survey of the biomodelling community44, such a model should, at a minimum, cover signal transduction, metabolism, and gene regulation, including transcription, translation, and degradation processes. While this survey pertained to a framework that mixed different model-types, an integrated model using DL would be advantageous for automatizing parameterization using different types of experimental data.

DL models have now been developed using prior knowledge for each of the major cellular subsystems. For signaling, we developed a model that predicts transcription factor (TF) activities or cell viability from ligand- or drug stimulation27. This model simulates signal propagation using a recurrent neural network (RNN) with a prior knowledge signaling network as a scaffold. We recently expanded this approach to simulate cancer cell signaling under perturbations with small molecule drugs, while simultaneously inferring their off-target effects28. For metabolism, a model has been developed that predicts metabolic rates from metabolite concentrations for E. coli bacteria45. Finally, for gene regulation, a model has been developed that reproduces the chemistry of TF-DNA binding and predicts gene expression levels from TF concentrations46. Using similar formulations, an integrated model of these processes could be reconstructed.

Saturating knowledge and accumulating data

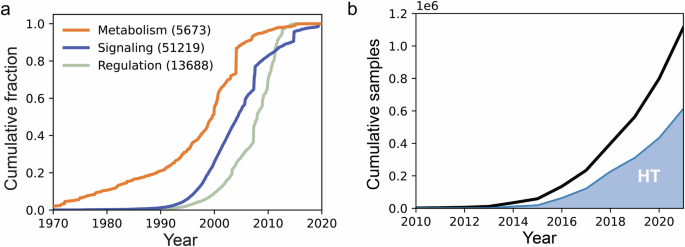

Our accumulated knowledge of molecular networks has now reached the genome-scale, thus enabling the creation of genome-wide predictive models. Advancements in both experimental47,48,49,50 and computational51,52,53,54 techniques have resulted in the curation of prior knowledge networks with thousand molecular interactions55,56. Prior knowledge of molecular relations is in principle finite since it is limited to specifying which interactions can take place if the participating molecules are present at appropriate concentrations. These relations place a structural constraint on which cell states are possible, although they are not always in effect, since not all molecules are present in every cell and cellular condition. Using this type of knowledge, large networks have been reconstructed for metabolism, signal transduction, and gene regulation55,56,57,58. An analysis of the first publication date for the references behind each interaction suggests that the rate of new discoveries is slowing (Fig. 2a). One interpretation may be that our prior knowledge of molecular interactions is reaching completion, although other possible interpretations may include a shift in research interests from basic biochemistry, or a lag between discovery and addition to databases. In particular, for the gene-regulatory network, the low coverage of interactions with literature support (8%, corresponding to less than one interaction per gene) may reflect a shift in the valuation of evidence, from individual published studies to inclusion in public databases.

a Prior knowledge by date of discovery. Interactions for metabolism (biochemical reactions and transport in Human179), signaling (protein-protein interactions in OmniPath56), and gene regulation (transcription factor-gene interactions in Dorothea58) by publication date of the oldest reference in the database. The total number of interactions with at least one PubMed reference is given in parenthesis and covers 50%, 98%, and 8% of the total interactions respectively. b Human transcriptomics samples in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) using RNAseq technology. A majority are from studies that include more than 250 samples, here labeled as high throughput (HT).

Simultaneously, the amount of well-annotated high-throughput data continues to increase rapidly. It can in principle increase infinitely, as it quantifies the cell state or phenotype under particular experimental conditions. To successfully model these data, both the experimental design (or metadata) and the cellular responses should ideally be recorded in databases. One such database, the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database59, has now surpassed a million human samples (Fig. 2b). There are public datasets14,15,16,60,61,62, that cover numerous perturbations such as gene knockouts, and stimulation by different drugs and ligands, in thousands of cell-lines, e.g., the CLUE platform hosts transcriptome profiles for more than 780,000 unique conditions16. These offer a vast amount of data to study and model the transcriptomic profile of diseased and perturbed samples in bulk, or even at the single-cell level.

Analyzing samples at the single-cell level, via molecular barcoding (e.g., nucleotide barcoding), has enabled the characterization of groups of cells in heterogeneous populations, which has allowed for a detailed characterization of cell types in different organs63. This can be particularly useful for clinical tumor samples, where the mixture of different cell types and their individual states would be challenging to deconvolute from bulk measurements64. After identifying individual cell types in a sample, it is possible to perfume pseudo-bulking, an analysis where gene expression data from cells derived from the same cell type is aggregated into distinct pseudo-bulk samples, reducing the impact of technical variability and dropout effects, often present single-cell RNA sequence data. Single-cell analysis has also allowed the exploration of variability in seemingly homogeneous cell populations65. Finally, the developments in molecular barcoding have also enabled systematic screening of combinations of stimuli, e.g., the transcriptomic response to 420 different drug combinations was measured in a pooled experiment, by using unique barcodes for each drug66.

Using different experimental techniques, molecular quantities of different modalities are now routinely characterized at the genome-scale67, including metabolite concentrations (metabolomics), concentrations of mRNA transcripts (transcriptomics), protein concentrations (proteomics), and protein phosphorylation levels (phospho-proteomics), which relates to their signaling state. It is also increasingly common to quantify multiple data types for the same group of cells or subjects (multi-omics)67 and, alternatively, to study the same set of cell lines with different techniques in different studies, e.g., one study-related metabolic profiles to differences in growth rate61, among the 60 cancer cell lines in the NCI60 panel, while another quantified their signaling responses to different drugs using phospho-proteomics62. However, so far it has proven challenging to integrate data from different studies, data modalities, and conditions67. This is in part due to a lack of unified analysis frameworks and because of difficulties in handling samples and subjects with missing data.

Proposed structure for an integrated model

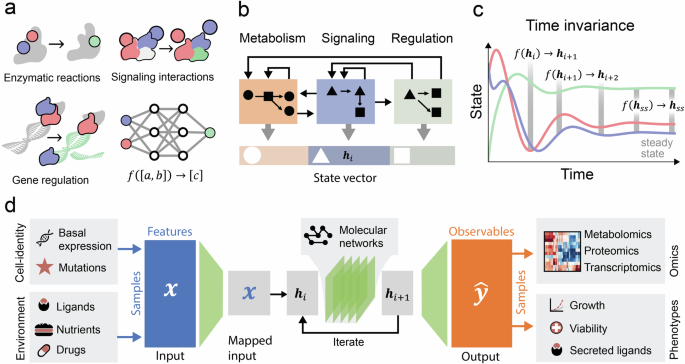

The activity of a cell consists of a series of molecular interactions that alter its molecular composition. To model these processes, the interactions could be represented by subfunctions that approximate the input-output relations between the molecular quantities involved (Fig. 3a). These interactions can be broadly classified as belonging to a particular cellular subsystem such as metabolism, signaling, or gene regulation that interact through shared molecular quantitates. A unified model may be constructed from a large number of such relations (Fig. 3b). For example, an enzyme can synthesize a metabolite that affects a signaling protein in control of a TF that regulates the expression of a gene. Such a modular structure with well-defined processes acting on state variables corresponding to observable molecules would ensure the model’s interpretability.

a Neural networks can approximate input-output relations between biomolecules such as metabolite concentrations, phosphorylation states of proteins, and transcription factor activities. b Integrated processes, the state vector partitioned into classes such as metabolite concentrations, signaling states, and protein concentrations. Each class is updated by independent functions that interact through their dependencies on the shared state space. c State trajectories constructed from repeated applications of a function on the state. d Inputs (x) describing the samples’ condition are mapped into their corresponding state elements. Analogously, outputs (ŷ) are extracted from the state to omics data and phenotypes. Prior knowledge of molecular networks is encoded into the architecture that updates the state vector.

As for many other physical systems, it can be assumed that these molecular functions do not directly depend on which cell type, or cellular compartment they occur in, i.e., that they are space invariant. It can be assumed that the de facto observed differences between cells and compartments originate from differences in molecular concentrations and post-translational modifications that can all be considered inputs to the functions. The use of invariances has been found useful in other neural network applications as it allows parameters to be shared between seemingly different conditions17, e.g., for image recognition, where the same convolution function is applied across all parts of an image. A potential challenge for this is the existence of cell-type-specific versions of molecules, such as proteins translated from genes with multiple splicing variants, i.e., isoforms. These may either be represented by independent functions or integrated into a unified function by using the isoform composition as an additional input. Another challenge may be ambient environmental factors such as temperature or pH that affect biochemical rates and thus the input-output relations, but in principle, these could also be used as input.

It can also be assumed that only molecular quantities, not the functions themselves, change over time, i.e., that they are time-invariant. This implies that molecular trajectories can be constructed from repeated application of the same functions (Fig. 3d), with different inputs at different times, starting with some initial condition and potential perturbations. Based on this assumption, time dynamics can be simulated using recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which are DL architectures that iteratively model sequential operations17, and which have as output intermediate hidden states of a model, that are used as input to calculate the next state. Black box RNNs have been used to recapitulate predictions by ODE models of signaling68 and we have used an RNN to directly model signal propagation from ligands to transcription factors, under the assumption that they reach a (pseudo-) steady state27.

A unified model operating on defined molecular quantitates allows for a straightforward mapping of inputs, and extraction of outputs. In this formulation, the cell state is expressed as vectors of molecular features, such as transcription factors, metabolites, proteins, etc. The inputs encode the cell type, environment, and perturbation of each specific sample (Fig. 3e). A mapping submodule can then assign the inputs to the affected molecules, for example drugs can be mapped to their targets, mutations to the affected proteins, and ligands to their receptors. The differences between cell types can be encoded through their basal molecular concentrations. Analogously, predictions pertaining to experimental data can be extracted from the state of the corresponding molecule, e.g., the expression of a gene from the representation of its mRNA concentration (Fig. 3e). The cell state is also a suitable input for submodules that predict cellular phenotypes, such as cell viability. For this, the state as a whole may be used or a knowledge-based subset, e.g., a core set of TFs that regulate cell proliferation has been used to predict viability9. This general representation would allow virtually any experimental conditions in any cell type to be integrated using the same model with different inputs. Because cellular processes are known to operate at different timescales, it would sometimes be warranted to separate slower processes into separate conditions, that can be simulated independently.

The purpose of the model is to predict unobserved cell states and the effects of untested perturbations for drug development. To train the model, the difference between expected and predicted values of the molecular quantities and phenotypes can be minimized using Mean Squared Error or the negative log-likelihood. This can be done for the final steady state of the model or alternatively across different iteration steps corresponding to integration across multiple time points. For single-cell data the model could be trained on pseudo-bulked profiles of each cell type, alternatively, the full distributions of gene expression in each specific cell type may be used a formulation inspired by evidential deep learning69, where the model estimates the statistical moments of an output distribution. To confirm the model’s ability to extrapolate to unseen perturbations, cross-fold-validation should be utilized by holding out perturbations during training that are dissimilar from the ones used in each training fold. Finally, experimental validation is necessary to evaluate interesting results of perturbations and states, where no experimental data exists, and to confirm these findings.

In the long term, one could envision that the neural networks could also model the experimental setting so that much less preprocessing would be required. Currently, preprocessing is a challenge due to differences in sequencing depth (and dropout) as well as differences in experimental protocol, such as RNA extraction, proteomics methods, etc. The cells of individuals represent natural experiments that perturb the input to an idealized cell. Cancer corresponds to a subspace of these perturbations. The challenge that these models could address is that the circumstances of every specific cancer are slightly different, and the optimal treatment (such as a currently existing or putative drug) will be patient-dependent (i.e., the motivation for precision medicine). These models could act as a scaffold to unify data from different circumstances to predict which treatment has the potential to be effective in this particular case. Predictive models (such as neural networks) have the advantage over descriptive (statistical) models that they may extrapolate to make a prediction in a case that has previously not been observed. Although in practice, models may not be directly deployed in clinics, they may help provide biomarkers to stratify patients into different treatment regimes that can be clinically tested.

Challenges and limitations

For models based on prior knowledge, the accuracy and completeness of the networks are of high importance. It can be expected that the prior knowledge both includes miss-annotated interactions and that it is incomplete. Critical examination and curation of interactions that are found to have high importance for the model predictions, in combination with validation experiments if the evidence is dubious, may be required to alleviate the limitation of miss-annotations in the prior knowledge. The incompleteness is expected to decrease as knowledge accumulates further, but this could also be addressed by including terms that model the influence of unknown factors70. If these terms significantly improve the model fit and generalization, they may constitute novel interactions to be experimentally validated, although inference of protein-protein interactions would not be the main goal of this endeavor. Similarly, processes beyond the model’s scope may manifest as missing interaction between molecular species, e.g., effects of splicing variants, microRNAs, or epigenetic modulation. An analysis of which conditions cause the model to fail and which measurements are affected may provide insight into the importance and magnitude of external influences.

Missing values and other irregularities often occur in biological data, and can be problematic for modeling. This may involve data collected from different cells at different time points, batch-batch variation between different groups of samples, or failed phenotype measurements67. Although, not apparent directly from their formulation, by applying a few modifications, DL models are well suited to handle these issues. Because ANNs estimate parameters using some version of stochastic gradient descent (SGD), missing data points can be omitted from the gradient calculations and allowed to take on any value. Furthermore, because SGD predicts gradients for the input variables, missing values can be automatically estimated to best agree with the experimental observations. In principle, batch effects could be accounted for by modeling differences in experimental equipment or other confounding variables. This type of “end-to-end” parameterization compared to manual feature selection, and standardization, simplifies the analysis and has proven useful in areas such as image processing17. Furthermore, semi-supervised learning approaches have been established to train models in cases where output data is not available for all of the samples71.

Discrete RNNs that may be used to simulate cellular dynamics are coarse-grained by design, which may pose a challenge for detailed simulations. While this limitation could in principle be circumvented using continuous time RNN architectures, these have hitherto relied on ODE solvers and thus suffer from issues with speed and scalability72. For some problems there exist closed-form approximations of the dynamics that can be used directly in the RNN, thereby achieving speedups by several orders of magnitudes72. Notably, a direct correspondence has been established73 between an RNN with specific architecture and a common numerical ODE solver, thereby further reducing the gap between the two approaches.

Applications and outlook

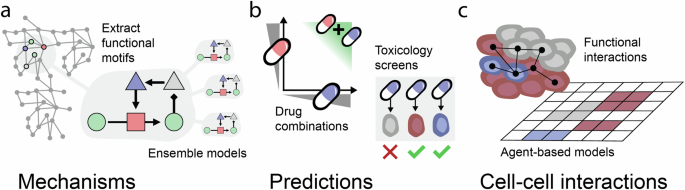

If successfully implemented and trained, these models would provide a succinct representation of cellular states and dynamics. This is expected to have many applications. The structured relation between state variables enables mechanistic interpretation of the modeling results (Fig. 4a). This may provide insight into emergent behavior and non-trivial dynamics, such as complex feedback structures that are not apparent in smaller-scale models13.

a Condition-specific functional motifs may be extracted from larger models. Ensembles of models may address model-model variability. b Synergistic effects of drug combinations may be predicted. Models of healthy cells could be used to anticipate toxicity effects. By modeling the effects of drugs in both healthy and diseased cells of different types, toxicity effects can be simulated. This can help estimate which drug combinations and doses will be tolerated to select promising candidates for further experimental or clinical validation. c The functional exchange of metabolites or ligands between cells of different types may be enquired. Artificial neural network models may act as surrogates for rules in agent-based models of cell-cell interactions.

Models may also be used to predict responses to non-tested conditions and counterfactuals (Fig. 4b). This may have applications for drug discovery, for example, drug resistance can be mitigated by drug combinations4, however, this is challenging to screen for experimentally as it grows exponentially for high-order drugs combinations. Another application may be to predict the effects of drugs on healthy cells. Drugs normally have off-target effects, and while this is sometimes important for their effectiveness74, it can affect healthy cells adversely and prevent the drugs’ translation to clinical use.

Yet another application may be to study cell-cell interactions (Fig. 4c). It is common to interrogate this through the expression pattern of ligands and their receptors in different cell types75, and this principle could be advanced to predict the effects on downstream signaling targets and predict which ligands and metabolites are secreted. One way to simulate the effects of cell-cell interactions at scale is through agent-based models (ABM) that represent different cell types by rules that describe their input-output relations76. However, the rules used in ABM models (such as Boolean models of signaling) are typically manually encoded, which is laborious and biases the result. It has been shown that these rules can be substituted by DL models77, e.g., allowing an ANN to model the complete signaling structure which incorporates multiple potential logical rules, which could relieve the need for manually defining the interactions, thus allowing for rapid data-driven model construction.

After constructing models that can simulate cellular responses and cell-cell communication, -potentially with single-cell resolution, the next natural step is to make use of clinical data for patient-level predictions. For example, the proposed framework may be used to map genomic mutations and gene expression for individual cell types, via signaling, creating this way interactome-based DL models that can include the transcriptomic and genomic identity of cells as input. Then the model could leverage approaches where given the single-cell gene expression profile of individual patients and the identification of each cell type present, the patient response can be predicted78.

The aim of constructing integrative models is to enable end-to-end simulation of genotype-phenotype relations. Such a project may help bridge the areas of metabolism, signaling, and gene regulation that are currently mostly studied in isolation. Through simulations, models will allow rapid generation and testing of hypotheses that would be impractical or impossible in the lab and clinical setting. This is anticipated to have many applications, for identifying drug targets, biomarkers, and treatment options.

Responses