Tradeoffs between the use of improved varieties and agrobiodiversity conservation in the Sahel

Introduction

In Sub-Saharan Africa, agricultural yields still lag behind those in other regions of the world1,2,3,4. This is even worse in the Sahel region, where farmers are facing many challenges due to climate change5,6,7. Since the 1980s, substantial efforts from Sub-Saharan African governments and international research institutes have led to the development and diffusion of improved varieties8,9. There is widespread evidence that the use of improved varieties has affected crops yields10 and smallholder farmers’ well-being positively in Sub-Saharan Africa11,12.

The use of improved varieties is often also argued to contribute to biodiversity conservation, in the sense that if the use of local varieties still prevailed, more land would have been needed, and the loss of forests and grasslands, the reduction in biodiversity and the extinction of wild species would have been disastrous13. However, a recent strand of literature shows that agricultural intensification, including the use of improved varieties, may threaten biodiversity, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa2,14,15. In other words, production gains, through the use of intensification methods, including the use of improved varieties, may occur at the costs of biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa. This raises the issue of the existence of possible tradeoffs between the use of improved varieties and (agro)biodiversity conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The issue is of high policy relevance. On the one hand, the application of improved production technologies, including the use of improved varieties, is a necessity for improving per capita food production and reducing food deficits in the developing world13. On the other hand, biodiversity conservation, especially crop/varietal diversity conservation, is also a prerequisite for (future) food and nutrition security. In Sub-Saharan Africa, more than one in four people are undernourished and malnourished16, and hunger is expected to increase significantly by 203017. In addition, climate change is hitting Sub-Saharan Africa especially hard5. Crop/varietal diversity conservation in situ and ex situ offers a global solution, in the sense that it helps increase the number of food options, including more nutritious food, create climate-resilient crops varieties, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and ensure food security for future generations18.

This paper measures spatial varietal diversity and examines the effects of growing improved varieties of pearl millet and groundnut on varietal diversity on farms, taking advantage of household- and farm-level data in two countries of the Sahel region (Mali and Niger) in 2019. According to the dataset, which comes from a large-scale baseline survey conducted in the context of the climate-smart agricultural technologies (CSAT) project in Mali and Niger, developed by the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) and funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, pearl millet and groundnut are cereal and legume crops that come first, in terms of a number of plots and planted area. Pearl millet and groundnut are important crops for responding to food security and nutrition challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa and have been associated with poverty reduction through increasing household income12,19.

We use ecological indices to measure spatial pearl millet and groundnuts diversity on farms. Then, we model (through a two-equation system) a representative farmer’s decision-making of growing an improved crop seed (over other crop seeds) and its effect on on-farm diversity of crop varieties. The model is estimated for a sample of 3131 pearl millet- and groundnuts-producing households using the maximum likelihood (ML) approach of the seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) model. We find greater richness of pearl millet varieties in Niger than in Mali, whereas both countries are not different in terms of the richness of groundnuts varieties grown. We also find that the diffusion of improved pearl millet varieties contributes to fewer varieties grown in Niger, whereas it contributes to more varieties grown in Mali. In the case of groundnuts production, the diffusion of improved varieties does not displace the other varieties grown in Mali and Niger.

Our contribution is twofold. First, we contribute to the debate on the existence of possible tradeoffs between agricultural intensification (through the use of improved varieties) and (agro)biodiversity conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa, focusing on both cereal and legume crops. Second, we present the case of the Sahel region, one of the Sub-Saharan regions most affected by hunger and malnutrition.

Results

We first document the spatial diversity of pearl millet and groundnut varieties grown in Mali and Niger. The surveys were able to identify and name improved pearl millet and groundnut varieties and pearl millet and groundnut landraces grown by farmers, based on farmers, extension agents and researchers’ feedback. Farmers have local (or common) names for improved varieties and enumerators were able to link local names with scientific names, based on the name of the variety provided by a specific extension agent to a specific farmer. Most of identified improved pearl millet and groundnut varieties have been developed by the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) and its national partners, including the Institute of Rural Economics (IER) in Mali and the Niger Institute of Agricultural Research (INRAN). ICRISAT, IER and INRAN were partners in the implementation of the CSAT project activities. The least recent year of release of the identified improved varieties is 2010 for pearl millet and 2011 for groundnut, based on information retrieved from the online databases of pearl millet and groundnut programs of ICRISAT.

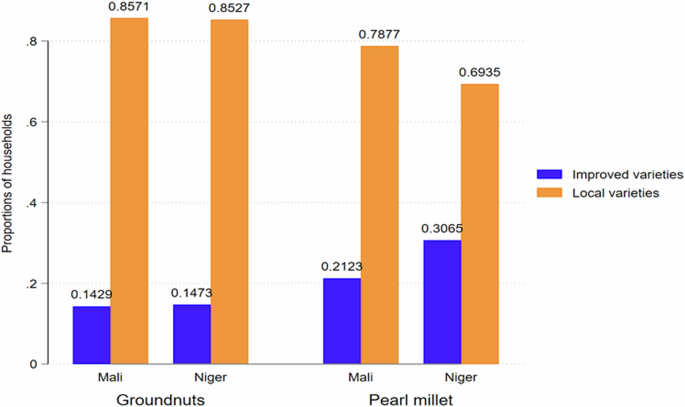

In the case of pearl millet production, the surveys conducted in both countries registered 914 and 1602 millet-producing households in Mali and Niger, respectively. Figure 1 shows the proportions of households growing improved pearl millet varieties on their plots. In both countries, the proportions of households growing improved pearl millet varieties were lower than those growing local varieties. In Mali, 21.23% of households were growing improved varieties, while in Niger, 30.65% of households were growing improved varieties. The same applies to the land allocated. In Mali, 24.85% of the total pearl millet area were dedicated to improved pearl millet varieties, while in Niger, 30.15% of the total pearl millet area were dedicated to improved pearl millet varieties.

This figure shows the proportions of adopters (from 0 to 1) by crop and country. N = 1271 and 1860 observations in Mali and Niger, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source data file. Analyses were performed in STATA 17.

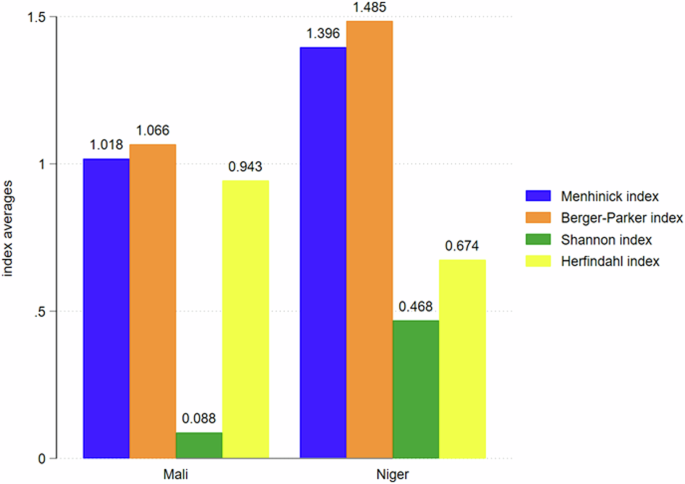

Figure 2 shows the average values of spatial diversity indices of pearl millet varieties grown in Mali and Niger. The average value of the Menhinick index (1.396) was higher in Niger (two-sample two-sided t-test: p = 0.000) than in Mali (1.018), suggesting greater richness of pearl millet varieties on farms in Niger, when standardized by area. In terms of proportional abundance, the average value of the Shannon index (0.468) was higher in Niger (two-sample two-sided t-test: p = 0.000) than in Mali (0.088), suggesting the proportional abundance of some pearl millet varieties in Niger than in Mali. Finally, in terms of specialization, Malian farmers tend to specialize more in a single millet variety than Niger farmers do. The average value of the Herfindahl index (0.943) was higher in Mali (two-sample two-sided t-test: p = 0.000) than in Niger (0.674).

Average values are reported for each diversity index in each country. N = 1271 and 1860 observations in Mali and Niger, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source data file. Analyses were performed in STATA 17.

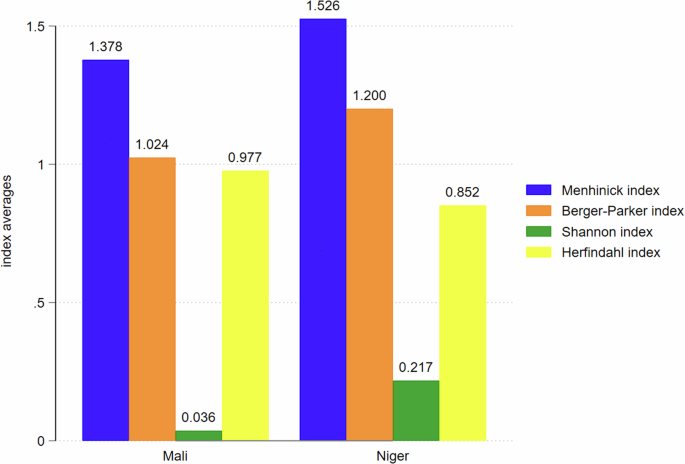

In the case of groundnut production, the surveys conducted in both countries registered 357 and 258 groundnut-producing households in Mali and Niger, respectively. In Mali and Niger, as for the pearl millet production, the proportions of households growing improved groundnuts varieties were lower than those growing local varieties (see Fig. 1). In Mali, 14.29% of households were growing improved varieties, while in Niger, 14.73% of households were growing improved varieties. The same applies to the land allocated. In Mali, 19.44% of the total groundnut area were dedicated to improved groundnut varieties, while in Niger, only 1.37% of the total groundnut area were dedicated to improved groundnut varieties. Figure 3 shows the average values of indices of the spatial diversity indices of groundnuts varieties grown in Mali and Niger.

Average values are reported for each diversity index in each country. N = 1271 and 1860 observations in Mali and Niger, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source data file. Analyses were performed in STATA 17.

Regarding the richness of groundnuts varieties grown, we found that the difference between the average values of the Menhinick index in Mali and Niger was not statistically significant (two-sample two-sided t-test: p = 0.232), suggesting that both countries are not different in terms of richness of groundnut varieties grown. However, the average value of the Berger-Parker index (1.024) was lower in Mali (two-sample two-sided t-test: p = 0.000) than in Niger (1.200), suggesting the relative abundance of some groundnut varieties in Niger than in Mali. The abundance of some groundnut varieties in Niger than in Mali is confirmed by the fact the average value of the Shannon index (0.217) in Niger was higher (two-sample two-sided t-test: p = 0.000) than in Mali (0.036). Finally, Malian farmers tend to specialize more in a single groundnut variety than Niger farmers do, as the average value of the Herfindahl index (0.977) in Mali was higher (two-sample two-sided t-test: p = 0.000) than in Niger (0.852).

Effects of the use of improved pearl millet varieties on on-farm pearl millet diversity

This section presents two sets of empirical results. First, we present the effects of the use of improved pearl millet varieties on on-farm pearl millet diversity in Mali. Second, we present the effects on on-farm pearl millet diversity in Niger. For both sets of results, we ran the seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) model, using the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation approach. The models are estimated with controls such as household characteristics (age, sex, education, household size and income), farm characteristics (farm size, number of farm plots, number of flat plots, number of fertile plots, irrigation and distance to field from residence), market characteristics (distance to nearest town, distance to nearest market and transport fare to the nearest urban area) and agro-ecological zone (rain zone and non-rain zone).

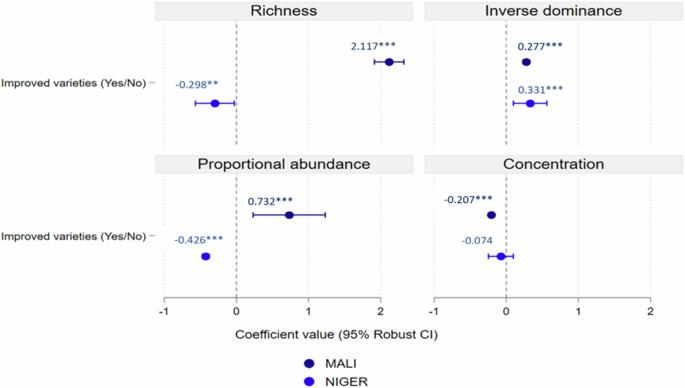

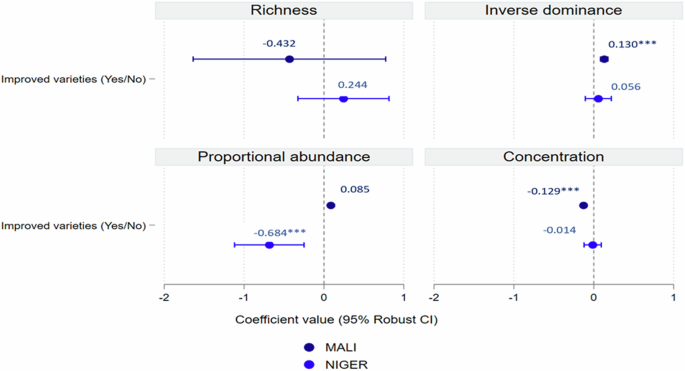

Figure 4 presents the estimates of the SUR model, based on Malian and Niger pearl millet-producing households, where the spatial diversity concepts are the richness (the Menhinick index), the inverse dominance (the Berger-Parker index), the proportional abundance (the Shannon index), and the concentration (the Herfindahl index). We found that, in Mali, growing an improved pearl millet variety had a positive and significant effect on the richness and the proportional abundance of pearl millet varieties, and a negative and significant effect on the specialization of farmers in a single pearl millet variety. In addition, we found that farm characteristics such as the farm size, the availability of an irrigation system, the slope and fertility of the soil, and the household size were the determinants of on-farm millet diversity. First, the richness of millet varieties was associated with small households. Second, the specialization in a single pearl millet variety was higher in small and less irrigated farms. Finally, we found that income was a determinant of households’ use of improved pearl millet varieties. Households with higher income were more likely to grow improved pearl millet varieties (see the regression results in the appendix file and the Zenodo repository).

Points are coefficients values of the SUR regressions (Robust estimation of standard errors and 95% confidence interval of the values of the coefficient). Richness, inverse dominance, proportional abundance and concentration are spatial diversity concepts measured by the Menhinick index, the Berger-Parker index, the Shannon index and the Herfindhal index, respectively. ***,**,*: coefficient values are statistically significant at 1, 5, or 10% significance level, respectively. N = 913 and 1602 observations in Mali and Niger, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source data file. Analyses were performed in STATA 17.

Figure 4 also presents the estimates of the model, based on the Niger millet-producing households. Contrary to the Malian case, we found that growing an improved pearl millet variety had a negative and significant effect on the richness and proportional abundance of pearl millet varieties. Growing an improved pearl millet variety was associated with less richness of pearl millet varieties and less abundance of some pearl millet varieties. As in the Malian case, we found that farm characteristics and household size were determinants of on-farm pearl millet diversity. The richness of millet varieties was associated with small and more fertile farms, and small households. In addition, as in the Malian case, households with higher income and living in the less rainy zone of the country were more likely to grow improved pearl millet varieties (see the regression results in the appendix file and the zenodo repository).

Effects of the use of improved groundnut varieties on on-farm groundnut diversity

Figure 5 presents the estimates of the SUR model, based on the Malian and Niger groundnut-producing households. The models are estimated with controls such as household characteristics (age, sex, education, household size and income), farm characteristics (farm size, number of farm plots, number of flat plots, number of fertile plots, irrigation and distance to field from residence), market characteristics (distance to the nearest town, distance to nearest market and transport fare to the nearest urban area) and agro-ecological zone (rain zone and non-rain zone).

Points are coefficients values of the SUR regressions (Robust estimation of standard errors and 95% confidence interval of the values of the coefficient). Richness, inverse dominance, proportional abundance and concentration are spatial diversity concepts described by the Menhinick index, the Berger-Parker index, the Shannon index and the Herfindhal index, respectively. ***,**,*: coefficient values are statistically significant at 1, 5, or 10% significance level, respectively. N = 356 and 258 observations in Mali and Niger, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source data file. Analyses were performed in STATA 17.

We found that growing an improved groundnut variety had no effect on the richness and proportional abundance of groundnut varieties in Mali. It also had a negative and significant effect on the specialization of households in a single variety. In other words, in Mali, growing an improved groundnut variety was not associated with less richness of groundnut varieties and specialization in a single variety. In addition, the farm size was a determinant of the richness index. Big farms were associated with less richness of groundnut varieties. Contrary to the millet case, the household’s income and the fact of living in the less rainy zone of the country were not determinants of the use of improved groundnut varieties (see the regression results in the appendix file and the Zenodo repository).

In Niger, growing an improved groundnut variety had no effect on the richness of groundnut varieties, but a negative and significant effect on the proportional abundance of some groundnut varieties. In other words, growing an improved groundnut variety is not associated with less richness of groundnut varieties. The farm characteristics, such as the farm size and the soil fertility, and the fact of living in the rainiest zone of the country, affected the richness of groundnut varieties negatively (see the regression results in the appendix file and the Zenodo repository).

Discussion

The use of improved varieties can make a large contribution to improving per capita food production and reducing food deficits in the developing world13. Whether production gains, through the use of improved varieties, may come at the cost of losses in agricultural biodiversity is a critical question, especially for the Sahel region, one of the Sub-Saharan regions most affected by hunger and malnutrition16.

The evidence presented in this paper indicates greater richness and a higher proportional abundance of some specific pearl millet varieties on farms in Niger. Regarding groundnut production, both countries conserve an equal richness of groundnut varieties, but Niger still has a higher proportional abundance of some specific groundnut varieties. A possible explanation is that, with the same richness of groundnut varieties in Mali and Niger, Niger farmers dedicate small land to improved groundnut varieties, implying a higher proportion of local groundnut varieties in Niger. Some recent studies confirmed that African rural households-maintained crop/variety diversity20,21,22. In fact, increasing crop/variety diversity opens market opportunities for households, while still contributing to self-consumption21.

We further found that growing an improved pearl millet variety had a positive and significant effect on the richness of pearl millet varieties on farms in Mali, and a negative and significant effect in Niger. Therefore, the introduction of improved pearl millet varieties in both countries contributes to more varieties grown in Mali and fewer varieties grown in Niger. To understand the results of millet in Niger, one needs to consider that there is an emphasis on early maturity for millet in the country. Therefore, most of the cultivars grown in the country tend to have that trait. Due mostly to the recurrence of early cessation of rains, most farmers emphasize that they need early maturing varieties. In addition, in recent years, herders tend to come back early from the north where animals graze during the rainy season. The early cessation of rains in the north makes them return early and farmers need to harvest before they come back.

In the case of groundnut production, we found that growing an improved groundnut variety had no significant effect on the richness of groundnut varieties in Mali and Niger. Therefore, contrary to the case of pearl millet production in Niger, the introduction of improved groundnut varieties in the Sahel region does not displace the other varieties grown in both countries. These results show the existence of tradeoffs between agricultural intensification (through the use of improved varieties) and agrobiodiversity conservation of pearl millet in Niger and the need for policymakers to adopt policies that promote more environmentally sustainable pearl millet production. They also illustrate the choice made by farmers for different crop varieties in different countries, facing the introduction of improved varieties: to diversify or not to diversify? In some cases, they decide to focus on fewer varieties, whereas in other cases they decide to diversify. This is in line with some authors22 who showed that, in the Ghanaian context, it is not just crop/variety diversification over-specialization, but it depends on the dimension and the extent of diversification. They concluded that Ghanaian households need to diversify, but not infinitely; after some level of diversification, they need to specialize.

Apart from these core results, evidence also shows that household’s income and the agroecological zone are important determinants of the adoption of improved pearl millet varieties in Mali and Niger. But they are not relevant for the adoption of improved groundnut varieties. This is understandable, in the sense that improved pearl millet varieties and related inputs are less affordable in the Sahel region23, apart from those provided by international agricultural research institutes such as the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), national agricultural research institutes and NGOs24,25, and are designed to be climate-smart and minimize risk from the short, variable length rainy seasons of the Sahel region26. It is important to note that these institutions do not commercialize the improved varieties. Household and farm characteristics and the agroecological zone, including household size, farm size, soil fertility, the existence of an irrigation system, and the fact of living in the less rainy zone of the country, are also important determinants of the on-farm diversity of millet and groundnut varieties grown in Mali and Niger. These findings are in line with the literature on the determinants of crop diversity on farms in African countries20,21,22,27.

Several caveats are in order when considering the results. First, the research focused on 2 major cereal and legume crops. Although they are staple foods in the Sahel region, it would also be relevant to consider the other crops, as agrobiodiversity conservation involves between and within crop diversity conservation. Second, improved varieties are assembled from gene-to-gene combinations of several individual parents, including landraces where they could be genetically as diverse as the existing plant population in the farmers’ fields. Therefore, it is important to use both biophysical and socio-economic considerations to address this issue of identification of improved varieties. Third, the research focused on a specific aspect of biodiversity, which is agrobiodiversity. Deforestation is also a major environmental issue in the Sahel region. Between 2000 and 2020, Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger lost almost 15% of their forest28. However, the effects of agricultural intensification (through the use of improved varieties) on deforestation and biodiversity in the region is still unknown. Understanding these linkages is important to know if the promotion of improved varieties may come at the cost of losses in biodiversity in the Sahel region.

Methods

Survey design and data collection

The study was conducted in the context of the climate-smart agricultural technologies (CSAT) project in Mali and Niger. The CSAT project is an initiative of the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and implemented by National Agriculture Research System (NARS) partners and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) from Mali and Niger. Data were collected through rural household surveys conducted in Mali and Niger in 2019. The surveys were conducted in 4 regions in Mali (Kayes, Koulikoro, Segou, and Sikasso) and 4 regions in Niger (Dosso, Maradi, Tillabery, and Zinder). Figure 6 shows the countries and regions selected for household surveys. Enumerators collected information from 3131 cereals- and legumes-producing households in Mali and Niger. In each country, a multistage stratified sampling was used to select the surveyed households. First, 4 regions were selected, based on the intensity of cereals and legumes productions, agroecology, accessibility and security. Second, 8 communes were selected from these regions. Third, 5 intervention and 5 non-intervention villages were selected. The final stage was the random selection of the households in each village, based on a sampling frame of households provided by the extension agents.

Retrieved from IITA’s Geographical Information System.

The survey was carried out in all the selected CSAT project regions, communes, and villages. To guide against any possible spillover effects, the intervention and non-intervention households were selected from the same communes and villages with similar characteristics, but the non-intervention villages were far from the intervention villages. In addition, to minimize the effect of selection bias, the non-intervention households were also selected using the same household eligibility criteria (agriculture as main occupation, residence in the village, willingness to give part of the farmland for trials, demonstrations, seed multiplications and improved seed dissemination), applied by the project to identify the project intervention households.

The survey was administered electronically using “Surveybe” and covered household composition and characteristics; knowledge and adoption of improved agricultural technologies, including improved varieties; training needs; input use and crop production, including cereals and legumes crops and varieties grown and area allocated to each; livestock production; crop utilization and household food and nutrition security, household total income; household assets, market access and migration; welfare and poverty evaluation; perceptions of climate change; awareness and damaging effects of pests and crop diseases; shocks and coping mechanisms. The quality of data was checked electronically. The data were uploaded in an electronic format immediately after collection, and supervisors checked automatically each enumerator’s start time, end time and GPS location, validating the interview and comparing its time and GPS location to that of other enumerators. A last layer of data quality check was done by the general supervisor, validating the interviews validated by each supervisor. In areas with limited electricity connectivity, each enumerator was given a battery pack to ensure that the tablets had the power to complete the interviews without problems.

Modelling farmer’s decision making and its effect

Following some authors20 who model farmer’s decision-making of growing an improved crop variety (over other crop varieties) and its impact on on-farm diversity of crop varieties, we developed a system of two equations. The system captures (1) farmer’s decision to grow an improved crop variety and (2) the impact of growing an improved crop variety on the spatial diversity of the crop varieties. We hypothesized that growing an improved crop variety generates benefits from the decision, in terms of yield and new traits or attributes29. If the farmer prefers the improved crop variety over the other crop varieties, this may lead to the abandonment or a reduction in area allocated to other crop varieties, reducing the spatial diversity of the crop varieties. The model is formulated for farmer i as follows:

Equation (1) describes the farmer i’s decision to grow an improved crop variety. She compares the expected utility from growing an improved crop variety, ({U}_{{modern}}), with the expected utility from growing other crop varieties, ({U}_{{others}}). She grows an improved crop variety if ({G}_{i}^{* }={U}_{{modern}}-{U}_{{others}} ,> ,0). ({G}_{i}^{* }) is a latent variable that captures the expected benefits from growing an improved crop seed. It is determined by a set of exogenous variables ({X}_{i}) and the error term ({e}_{i}). The farmer (i)’s observed decision to grow an improved crop variety is a binary variable ({G}_{i}):

Equation (2) describes the impact of growing the improved crop variety on the spatial diversity of the crop varieties. Let’s introduce another latent variable, ({I}_{i}^{* }), which captures farmer i’s diversification strategy. It is also determined by the decision to grow an improved crop variety ({G}_{i}), a set of exogenous variables ({Z}_{i}) and the error term ({u}_{i}). On farm, this diversification strategy may be approached by an index ({I}_{i}), which has the minimum value (underline{I}) and the maximum value (bar{I}):

Measurement of on-farm crop diversity

We measured the varietal diversity of cereals and legumes on farms by using ecological indices of spatial diversity29,30, especially the Menhinick index, the Berger-Parker index, the Shannon index and the Herfindahl index. Their choice is motivated by the following reasons. First, in terms of diversity concepts, the selected indices are apparent, spatial, and intra crops29. Second, they represent different dimensions of diversity, including richness, dominance, proportional abundance (or heterogeneity) and concentration30. Finally, they fit the information collected by the rural household surveys conducted in both countries (cereals and legumes varieties grown and percentage of area under cereals and legumes varieties grown).

The Menhinick index dr is a richness index, which represents the number of distinct plants of varieties of a specific crop in a defined geographical area such as a farm. It is computed as follows:

where S is the number of varieties of a specific crop and A is the total crop area on a farm.

The Berger-Parker index ({d}^{d}) is an (inverse) dominance index, which represents the relative abundance of a variety of a specific crop. It accounts for the frequency that a variety is counted. It is computed as follows:

where ({p}_{i}) is the crop area share occupied by variety (i).

The Shannon index ({d}^{e}) is a proportional abundance (or evenness) index, which combines the richness and relative abundance concepts. It is also called a heterogeneity index and is computed as follows:

The Herfindhal index ({d}^{c}) is a concentration index, which expresses specialization. It tells whether a single variety occupies the planted area. It is computed as follows:

Empirical estimation

The two-equation system may be perceived as a fully observed conditional recursive mixed-process model31. First, the two-equation system is a multiequation mixed model, as the two equations have different types of dependent variables. Equation 1 is a probit/logit model and Eq. 2 is a tobit model. Second, the system is recursive, as we have two clearly defined stages. The first stage, the probit/logit model, expresses farmer i’s decision to grow an improved crop seed, whereas the second stage, the tobit model, expresses the effect of the farmer i’s decision on the spatial diversity of the crop varieties. Finally, the endogenous variable ({G}_{i}^{* }) appears on the right-hand side of Eq. 2 as observed.

As explained31, the parameters of this fully observed conditional recursive mixed-process model can be consistently estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) approach of the seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR) model. It is important to note that the ML SUR provides consistent estimates of the parameters of a mixed-process simultaneous system when it is recursive and fully observed. In other cases of a mixed-process simultaneous system, the ML SUR approach may not be relevant. To fix ideas, the multiequation mixed model for farmer (i) can be written in a general form as follows:

where

({{boldsymbol{y}}}^{* {prime} }=left[{G}_{i}^{* },{I}_{i}^{* }right]), ({varepsilon }^{{prime} }=left[{e}_{i},{u}_{i}right]), ({{Delta }}=left(begin{array}{cc}0 & beta \ 0 & 0end{array}right)), ({{boldsymbol{x}}}^{{prime} }=left[{{boldsymbol{X}}}_{{boldsymbol{i}}},{{boldsymbol{Z}}}_{{boldsymbol{i}}}right]) and B = [α γ]. g1 (.) and g2 (.) are link functions.

To express censoring, we assume ({underline{tau }}_{ij}) and ({bar{tau }}_{ij}) as the lower and upper censoring threshold for ({y}_{j}). Therefore, the overall censoring range, that is the region of possible values of (left[{e}_{i},{u}_{i}right]) generating observable values for (left[{G}_{{boldsymbol{i}}},{I}_{{boldsymbol{i}}}right]) given (left[{X}_{i},{Z}_{i}right]) is the following cartesian product:

Let’s represent the zero-centered normal distribution by:

To express the observation-level likelihood, we define the probability distribution function for ({varepsilon }_{i}) as:

We also define an error link function that connects the error process to the outcome:

Thus, the observation-level likelihood is the ratio of two integrals over certain regions of the distribution ({f}_{{{boldsymbol{varepsilon }}}_{i}}), which is known given ({boldsymbol{Sigma }}) and the outcome of any multinomial choices:

Table 1 shows the variables used for the empirical estimation. Descriptive statistics and econometrics analyses were performed in STATA 17.

Responses