Transfer learning method for prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of biliary atresia

Introduction

Biliary atresia (BA) is a severe hepatobiliary disease in infants, characterized by obstructive cholestasis. It involves progressive fibroinflammatory obliteration of the extrahepatic biliary tree and rapid progression of intrahepatic biliary fibrosis1. It is the leading indication for pediatric liver transplantation, affecting 1:8,000 to 1:18,000 infants globally, often leading to end-stage liver disease by two years of life. The progression of BA can be slowed with Kasai portoenterostomy, a procedure that attempts to establish bile flow by removing atretic bile ducts and creating a liver–intestine anastomosis2. Treatment within 30 days offers the best chance of delaying or preventing transplantation. However, BA is typically detected late as it is challenging to identify in its early stages. Thus, early identification of BA remains a critical challenge in pediatric hepatology.

Abnormal direct or conjugated bilirubin measurements in new-borns with BA suggest the prenatal onset of liver dysfunction2,3. Our previous studies demonstrated the usefulness of prenatal ultrasonography in diagnosing BA, with the fetal gallbladder identified as a critical feature. This feature exhibited the best diagnostic performance as a single parameter, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) of 0.914 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.869-0.948)4,5. However, accurate diagnosis via ultrasonographic examination remains challenging due to the lack of expertise in diagnosing fetal BA, stemming from its low incidence rate in most hospitals.

One potentially promising method to enhance fetal BA diagnosis accuracy is utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) techniques. Among these techniques, deep-learning models have shown superiority or comparability to human experts in various medical data analysis tasks, such as diagnosing fetal central nervous system defects6,7 and fetal heart defects8. However, to our knowledge, no AI model based on ultrasonographic images has been developed for prenatal BA diagnosis. The success of AI models relies on large-scale data for optimal performance, posing a challenge in collecting data for rare diseases with low incidence rates, especially prenatal data. Given the consistency between the features observed in fetal gallbladders and those in infants with BA4,5,9,10,11, it is worth exploring whether learning from neonatal gallbladder ultrasonographic images could aid in identifying BA fetal gallbladders.

Transfer learning, a type of AI method, can leverage existing generalizable knowledge from related tasks to facilitate learning separate tasks using a small dataset12. In recent years, transfer learning has been increasingly utilized to construct medical image analysis models to overcome data scarcity13,14. However, no study has been conducted on transferring information learned from postnatal images to a fetal diagnostic model. Deep domain generalization (Deep DG) is an efficient and popular transfer learning method capable of generating new samples or domains at the image level and/or augmenting features at the feature level. Data or features are augmented or generated to enhance the corresponding attributes, such as shape, or bridge the gap between domains15.

Hence, this study aimed to develop a transfer learning method for the automatic and accurate identification of BA based on fetal ultrasonographic images of the gallbladder. Additionally, it offers a potential solution for AI research on rare congenital diseases.

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients in both training and test dataset

For model development and testing, we prospectively collected 7211 non-BA fetal gallbladder images from 3795 pregnancies and 1041 BA gallbladder images from 134 pregnancies between November 2017 and July 2023. These pregnancies were sourced from 20 hospitals across Northeast, Western (Northwest and Southwest), and Southeast China. A detailed flowchart of patients and images selection was depicted in Fig. 1.

The diagram provides a schematic illustration for the recruitment and allocation of participants in our study, including the training dataset and test dataset. SJ Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, BA biliary atresia, DB public database (provided by Zhou et al. in this study), GA gestational age, w week.

The training cohort comprised 4143 images from 2208 fetuses without BA and 689 images from 52 fetuses with BA from Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, and the proportion of fetuses with BA was 2.30%. To ensure the applicability of models across diverse populations, medical centers, equipment, and image qualities, they must demonstrate robustness to minor variations in image quality. Hence, we conducted additional assessments of the AI models under various simulated scenarios. In total, 3068 images from 1587 fetuses without BA and 352 images from 82 fetuses with BA were used for the testing datasets. Test cohort A consisted of 1140 images from 594 non-BA fetuses and 140 images from 38 fetuses with BA from 12 hospitals in Northeast China. The proportion of fetuses with BA in this cohort was 6.01%. Test cohort B included 1208 images from 618 non-BA fetuses and 88 images from 19 fetuses with BA from five hospitals in Western China, with the proportion of BA fetuses being 2.98%. Test cohort C comprised 720 images from 375 non-BA fetuses and 124 images from 25 BA fetuses from two hospitals in Southeast China, with the proportion of BA fetuses being 6.25%. The patients did not overlap among the three test datasets or the training dataset. Additionally, 200 images from 200 infants without BA and 200 images from 200 infants with BA from a public database, with the proportion of BA infants being 50%, were used to establish the transfer-learning model (TLM). Test cohort D, a subset of test cohort A, including 40 non-BA fetal ultrasonographic images and 20 BA fetal ultrasonographic images (the percentage of BA infants was 33.33%) was used for the reading study.

Comparison of the performance among the selected networks

Comparison of the performance among the ResNet, ConvNext, Swim Transformer, and EfficientNetV2 networks revealed that ResNet-18 demonstrated the best diagnostic performance, achieving an accuracy of 98.15% with the shortest training time of 3.62 hours, surpassing other selected networks. Accuracy values for the networks were presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Comparison of the performance between the basic deep-learning model (BLM) and TLM in predicting BA in fetuses

A comparison of BLM and TLM performance in predicting BA in fetuses highlighted the superiority of TLM. As illustrated in Fig. 2, TLM outperformed BLM in classifying BA across the three test cohorts. TLM achieved higher AUC values of 0.906 (95% CI 0.872–0.940) vs 0.793 (0.743–0.843) for test cohort A, 0.914 (0.875–0.953) vs 0.790 (0.727–0.853) for test cohort B, and 0.907 (0.869–0.945) vs 0.880 (0.838–0.922) for test cohort C. Notably, TLM improved prediction accuracy for BA cases significantly compared with BLM, with a mean sensitivity of 86.10% vs 67.81% (P < 0.05). Additionally, TLM exhibited specificity from 94.12% to 96.81% across the three test cohorts. Further detailed prediction metrics for each test cohort were presented in Table 1.

a The confusion matrix and ROC curves of both BLM and TLM in test cohort A (hospitals in Northeast China). b The confusion matrix and ROC curves of both BLM and TLM in test cohort B (hospitals in Western China). c The confusion matrix and ROC curves of both BLM and TLM in test cohort C (hospitals in Southeast China). The confusion matrix in green color present the result of BLM; the confusion matrix in red color present the result of TLM. BA biliary atresia, ROC receiver operating characteristic, BLM basic deep-learning model, TLM transfer-learning model.

Performance of TLM compared with performance of sonologists

The performance of TLM was compared with the performance of sonologists in test cohort D. TLM demonstrated a superior ability to identify BA, with a sensitivity of 90.00% (18/20), specificity of 82.50% (33/40), accuracy of 85.00% (51/60), positive predictive value (PPV) of 72.00% (18/25), and negative predictive value (NPV) of 94.29% (33/35). In contrast, initial diagnoses by sonologists yielded accuracies of 66.67%, 68.33%, and 76.67% for the three senior sonologists (P > 0.05), 71.67%, 70.00%, and 70.00% for the three junior sonologists (P > 0.05), and 60.00%, 51.67%, and 65.00% for the three rural sonologists (P > 0.05). The AUC achieved by TLM was significantly higher than that achieved by sonologists alone (AUC 0.862 [0.759–0.966] vs AUC 0.713 [0.563–0.862], P < 0.05). Additional performance metrics for the diagnoses were listed in Table 2. TLM completed a single image reading and diagnosis in only 0.02 seconds (s), significantly faster than the time required by sonologists (median [interquartile range (IQR)], 8.57 [5.06-11.01] s, Wilcoxon signed-rank test P < 0.001).

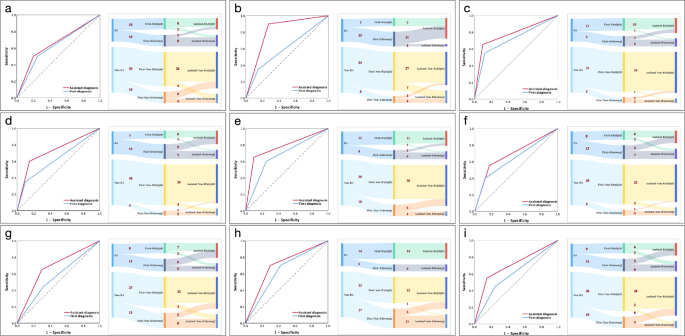

With TLM assistance, diagnostic ability improved significantly for all sonologists (Table 2); however, it remained inferior to independent TLM diagnosis. The final diagnosis was corrected from the wrong initial diagnosis in 40.00% (8/20), 68.42% (13/19), and 35.71% (5/14) for senior sonologists A, B, and C; 41.18% (7/17), 44.44% (8/18), and 35.29% (6/17) for junior sonologists D, E, and F; 45.83% (11/24), 26.09% (6/23), and 52.38% (11/21) for rural sonologists G, H, and I. However, this model may also misguide sonologists, leading them to alter an initially correct diagnosis to an incorrect one. The percentages of such conversions were 15.00% (6/40), 17.07% (7/41), and 4.35% (2/46) for senior sonologists A, B, and C; 9.30% (4/43), 2.38% (1/42), and 11.63% (5/43) for junior sonologists D, E, and F; while 16.67% (6/36), 2.70% (1/37), and 12.82% (5/39) for rural sonologists G, H, and I. Changes in diagnostic decisions for each sonologist were presented separately in Supplementary Table 1 and further summarized in Fig. 3.

a The ROC curve and detailed diagnostic changes in BA for senior sonologist A after receiving assistance from the TLM. b The ROC curve and detailed diagnostic changes in BA for senior sonologist B after receiving assistance from the TLM. c The ROC curve and detailed diagnostic changes in BA for senior sonologist C after receiving assistance from the TLM. d The ROC curve and detailed diagnostic changes in BA for junior sonologist D after receiving assistance from the TLM. e The ROC curve and detailed diagnostic changes in BA for junior sonologist E after receiving assistance from the TLM. f The ROC curve and detailed diagnostic changes in BA for junior sonologist F after receiving assistance from the TLM. g The ROC curve and detailed diagnostic changes in BA for rural sonologist G after receiving assistance from the TLM. h The ROC curve and detailed diagnostic changes in BA for rural sonologist H after receiving assistance from the TLM. i The ROC curve and detailed diagnostic changes in BA for rural sonologist I after receiving assistance from the TLM. ‘First-’ represents sonologists’ independent diagnosis; ‘Assisted-’ represents the second diagnosis with the assistance of TLM; ‘10’ or ‘8’ represent the specific number of cases, respectively. ROC receiver operating characteristic, BLMbasic deep-learning model, TLMtransfer-learning model, BAbiliary atresia.

Visual interpretation of the TLM model

Visual interpretation of the TLM model revealed significant insights. The heatmap, presented with a rainbow color map scale, highlighted regions of high relevance (red), medium relevance (yellow), and low relevance (blue). The gallbladder wall exhibited high prediction probability based on the heatmap’s location (Fig. 4).

The diagram provides the heatmap of both BA cases and Non-BA cases. BA biliary atresia.

Discussion

In this study, we successfully developed an intelligent diagnostic model for the prenatal diagnosis of BA by integrating neonatal and fetal gallbladder ultrasonographic images, which demonstrated excellent diagnostic accuracy, and higher than diagnoses made by sonologists.

Currently, the diagnosis of BA in clinical practice primarily relies on serological testing and ultrasonographic examination after evident jaundice symptoms appear in the neonatal period. Research on its prenatal diagnosis is limited. In our previous prospective cohort study, we found that 93.3% of BA fetuses exhibited gallbladder dysplasia on prenatal ultrasonography4. However, most doctors lack experience in the prenatal diagnosis of BA, and there is an absence of an objective basis for evaluating the gallbladder. The earlier International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG) guidelines16 did not routinely recommend gallbladder assessment using prenatal ultrasonography. According to the latest ISUOG guidelines17, identifying the gallbladder as a hypo-echoic structure in the upper fetal abdomen is optional, indicating an increasing focus on gallbladder evaluation.

The highest AUC value of our BLM based solely on fetal ultrasonographic images was 0.880 (95% CI 0.838–0.922). Given that BA is a rare disease, obtaining ultrasonographic images of the gallbladder prospectively before delivery is challenging. Through collaboration with multiple medical centers nationwide, we acquired only 134 cases of BA over the past seven years, making it the largest gallbladder dataset of BA fetuses reported in the literature. Expanding the sample size further to enhance the diagnostic accuracy of the model is difficult. We found that, in the process of exploring fetal BA ultrasonographic features, doctors benefited from learning the features of infant ultrasonographic images for diagnosing fetal BA. Hence, we hypothesized that intelligent learning from infant gallbladder images could enhance the accuracy of fetal BA diagnostic models. Our results confirmed that the TLM outperformed the BLM in all three test sets, and the overall diagnostic performance could be improved significantly, especially for the determination of the gallbladder in the BA group. This indicates that the addition of gallbladder images from the 200 infants with BA successfully enhanced the recognition of BA gallbladders in the model. Learning from children’s images to optimize diagnostic models for fetal-related diseases represents a breakthrough in prenatal AI diagnostic models. Moreover, the heatmap highlighted the most informative regions for AI diagnosis, with the gallbladder wall exhibiting the highest prediction probability. As the gallbladder wall is a crucial ultrasonographic characteristic for clinically diagnosing fetal BA9,11, this further underscores the reliability of TLM.

In the image-reading experiment, we observed that diagnostic accuracy was suboptimal for each level of doctor, and diagnostic performance was inferior to that of TLM alone, even with TLM assistance, reflecting the current clinical situation of BA prenatal diagnosis. This is attributed not only to doctors’ lack of diagnostic experience in BA but also to the contraction of the fetal gallbladder in the uterus causing significant variations in normal gallbladder ultrasonographic images, posing considerable challenges for doctors in prenatal diagnosis. As the largest prenatal diagnosis referral center in Northeast China, we encounter an increasing number of fetuses coming for consultation due to issues with the size and shape of the gallbladder. Most final diagnoses indicate normal gallbladder contractions. However, this suspected diagnosis places a heavy burden on pregnant women and their families. With TLM assistance, doctors’ accuracy in determining BA and normal fetal gallbladders has significantly improved, which holds crucial practical implications. Simultaneously, our diagnostic model also holds high diagnostic value for images captured by smartphones; thus, in the future, we can implement our model on smartphone terminals for more convenient clinical applications.

Our study possesses several strengths. Firstly, it was a prospective multicenter study that established the largest fetal BA gallbladder database. Secondly, our diagnostic model underwent testing across different regions, instruments, and image qualities in China. Its consistent performance across varying conditions underscored its potential for broader generalization. Thirdly, we successfully optimized the fetal diagnostic model through the application of transfer learning with infant images. This enhancement significantly improved the diagnostic accuracy of traditional models and served as an effective example for establishing prenatal intelligent diagnostic models for rare congenital diseases.

However, despite these contributions, some limitations must be addressed. Firstly, the BLM and TLM were established solely based on the deep learning of gallbladder ultrasonographic images. In cases where the fetal gallbladder cannot be visualized, our intelligent model is not applicable. As reported, non-visualization of the fetal gallbladder was associated with an incidence of BA of approximately 4.8%18. Furthermore, in our previous study, the gallbladder was visualized in about 86.67% of BA cases4. Additionally, in clinical practice, sonologists often monitor morphological changes in suspicious findings over time before making decisions, suggesting the need to incorporate video analysis into future studies. Furthermore, our previous study found that combining indicators such as right hepatic artery dilation, seroperitoneum, and enhanced intestinal echogenicity with a high-risk gallbladder can significantly enhance the accuracy of prenatal BA diagnosis. The development of a multimodal intelligent diagnostic model that incorporates additional information—such as gallbladder measurements, other ultrasonographic indicators, clinical information (e.g., maternal disease, gestational age, etc.), and biochemical test results—holds great promise for accurately diagnosing prenatal BA. Another limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size of the database. Despite considering the rarity of the disease and employing several methods to mitigate this limitation, the sample size remains small for AI research, potentially resulting in overfitting of the findings. Therefore, conducting a larger-scale multicenter validation of our system is necessary before widespread implementation in clinical practice.

The visualization rate of the fetal gallbladder increased as gestation advanced, reaching a plateau above 90%, which was maintained between 16 and 34 weeks19. Although the TLM showed stable results in predicting BA in fetuses between 22 and 36 weeks of gestation in our research, we still do not recommend applying the AI tool for routine screening currently. However, it could be a powerful auxiliary tool for the differential diagnosis of BA in cases with high-risk gallbladders during mid and late pregnancy.

In this study, we developed and evaluated a transfer learning method, the TLM, for diagnosing fetal BA, which outperformed the traditional deep learning method across various conditions, indicating its potential for broader generalization. Additionally, our study highlighted the significant diagnostic improvement achieved through the collaboration between AI and sonologists. We believe that this study offers a powerful approach for the prenatal diagnosis of BA, addressing the insufficient diagnostic abilities associated with poor prognosis. Moreover, the innovative framework for transferring postnatal information to prenatal analysis presented in our work serves as a valuable reference for establishing similar medical image analysis tasks.

Methods

Data sources and study population

Fetuses were recruited from the Shengjing Hospital, China Medical University, in Shenyang, Liaoning Province, China, serving as the training cohort from November 2017 to July 2023. From March 2020 to July 2023, ultrasonographic images of fetal gallbladder were prospectively gathered from hospitals across Northeast China (test cohort A), Western China (test cohort B), and Southeast China (test cohort C). Detailed information about the centers involved is provided in Supplementary Table 2. All participating centers adhered to identical inclusion and exclusion criteria (Supplementary Table 3). Raw data was collected with various ultrasound devices, the detail was displayed in Supplementary Table 4. All data collection was conducted by doctors with >10 years of experience in fetal ultrasonography. Additionally, an independent open-access dataset containing 200 images from 200 infants with BA and 200 images from 200 normal infants, provided by Zhou et al. 20, was used as the transfer learning dataset.

This prospective cohort study was part of the program of Shengjing Birth Cohort (Birthcohorts 2017-05-10-0000-00-00), and received approval from the Institutional Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University (2017PS264K). Besides, the research across multiple medical centers was obtained additional ethical approval in 2020 (2020PS227K) and was registered at www.chictr.org.cn (ChiCTR2200059705). Written informed consent was provided by participants.

Data preparation

All ultrasound images in JPEG or JPG format were directly applied in our study, which were directly exported from the ultrasound equipment. The video data was converted into still images of 0.5 s frame by frame and exported as JPEG format. The video data underwent initial conversion into frame-by-frame still images. Each converted image, along with freeze-frame images, was assessed and selected for inclusion, while irrelevant and blurred images were excluded. Two sonologists were tasked with capturing photographs of the original ultrasonographic images from test cohort C using smartphones vivo S3 and Huawei nova 7 before analysis. Subsequently, two senior sonographic experts reviewed all images, excluding those of poor quality. Given that each image contained irrelevant regions (e.g., dark regions near the image boundaries and textual information around the top regions), a bounding box encompassing the entire gallbladder was manually drawn by two sonologists using the free software ‘LabelImg’ (https://pypi.org/project/labelImg/). Simultaneously, each image was assigned a label indicating the final diagnosis of either BA or non-BA based on the results of the gold standard. Two other senior doctors conducted a double-check to ensure the appropriateness of the bounding boxes and labels. Two image augmentation techniques, ‘RandomResizedCrop’ and ‘RandomHorizontalFlip’, were subsequently applied to the training images. These strategies aim to replicate the diversity of real-world data, thereby enhancing the generalization performance of the model. Following data enhancement, all images were resized to 224 × 224 pixels.

Model development

We initially trained and validated several networks using the training data, including the Swim Transformer, ResNet, ConvNeXt, and EfficientNetV2. We then selected the most suitable network for establishing the model. The training cohort was first divided into training and validation datasets at a ratio of 8:2 at the case level for comparison. In this study, we developed and evaluated two types of AI architectures: BLM and TLM for intelligent diagnosis of BA. The BLM was trained exclusively using a training cohort comprising fetal ultrasonographic images, with the output predictions evaluated on external test datasets. Conversely, the TLM utilized a training cohort consisting of both fetal and infant ultrasonographic images, employing the Deep DG strategy. Initially, we generated synthetic samples from fetal and infant ultrasonographic images in the training cohort using a powerful technique called mixup21. By leveraging the advantages of mixup, models can learn more generalized representations that are better suited for real-world applications. The selected network was then trained with synthetic samples for BA prediction, resulting in a TLM. Finally, we used the test cohorts to assess the performance of both BLM and TLM and further evaluated the generalization ability of these models in various clinical scenarios. The entire procedure for model establishment is illustrated in Fig. 5.

a The process of network selection and basic deep-learning model establishment. b The process of the transfer-learning model establishment. c The testing process of the basic deep-learning model as well as the transfer-learning model. BA biliary atresia.

To interpret the prediction decision and recognize the prediction results, we deployed Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) for heat map generation. Grad-CAM is a powerful interpretation method for connecting an output class with the input image and the learned features to explain the image class. This method has been widely used in previous studies due to its compatibility with various models and its flexibility in integrating with any layer of a post hoc network22.

The design for the reading process

A new test cohort, cohort D was employed for the reading comparison between the TLM and sonologists with varying levels of expertise, as well as the efficacy of TLM assistance in clinical practice. Forty non-BA fetuses and twenty BA fetuses were randomly selected from test cohort A. Then, one image was randomly chosen from each fetus to serve as image data for test cohort D. A researcher not involved in data collection, preprocessing, and assessment process performed the entire random selection process. In total, test cohort D comprised 40 gallbladder images from 40 non-BA fetuses and 20 gallbladder images from 20 BA fetuses. Nine sonologists, including three senior sonologists (with >10 years of experience in fetal ultrasonography from Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University), three junior sonologists (with >5 years of experience, also from Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University), and three rural sonologists (with >10 years of experience from primary hospitals) were enlisted for the evaluation (Supplementary Table 5). All sonologists participating in the assessment were blinded to the follow-up results and were not involved in image quality control or labeling. The assessment comprised two reading processes: initial read and second read. The images from cohort D were presented on a screen, and the sonologists independently completed a questionnaire regarding their subjective evaluation of the target ultrasonographic images, making optional decisions regarding BA or non-BA. Their responses and reading times were recorded. The doctors were kept unaware of the final diagnosis, and an evaluation of the TLM-assisted diagnosis was conducted one month later. In the second reading process, the display settings differed, with the AI reference displayed parallel to the original images. Similarly, the sonologists independently evaluated the images, completed the questionnaire, and recorded their responses and reading times. The reading process design is illustrated in Fig. 6.

The diagram provides the reading process of sonologists at various levels. BA biliary atresia, AI artificial intelligence.

Model assessment and statistical analysis

Performance metrics for predicting BA included accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and AUC along with 95% CIs. ROC curves were generated, plotting sensitivity (true-positive rate) against 1-specificity (false-positive rate). DeLong’s test was utilized to compare AUCs. The diagnostic time required by all sonologists was described as the median [IQR]. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed to compare the time required by the TLM and sonologists. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P values < 0.05 indicated statistically significant differences. The analyses were conducted using the SPSS software package version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc Statistical software (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium).

Responses