Transition from irrigation with untreated wastewater to treated wastewater and associated benefits and risks

Introduction

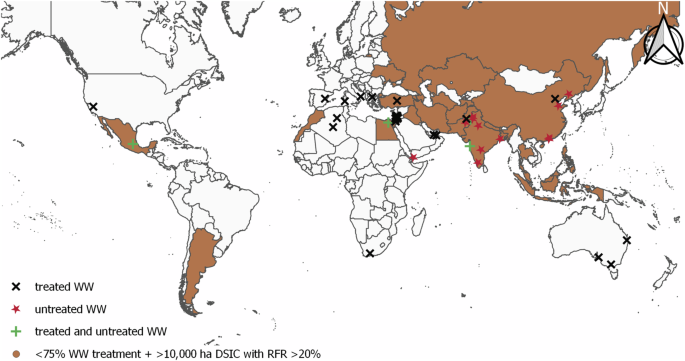

With growing population and increasing population density in urban agglomerations and megacities1 the pressure on regional water resources increases. Climate change may further exacerbate local water demands2. The reuse of wastewater for the irrigation of agricultural fields is one of the most powerful leverage points for more efficient utilization of water resources3. Such reuse of wastewater for irrigation in agriculture has evolved with the development of cities and water technologies and thus dates back several thousand years in different parts of the world4. Today, in some countries such as Israel, already 80% of the wastewater is recycled and used for irrigation5,6. Drechsel et al.7 estimated that globally roughly 30 million hectares of agricultural land are irrigated with untreated, partially treated, or diluted wastewater, by far exceeding the area of nearly 1 million hectares that is irrigated with treated, reclaimed wastewater. An overview of irrigation with wastewater of different degrees of treatment or wastewater-impacted surface water in different countries is shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Figure 1 shows that irrigation with treated wastewater was mainly studied in North Africa, Southern Europe, and Australia, whereas irrigation with untreated wastewater was mainly studied on the Indian subcontinent and in East Asia. Large data gaps exist, therefore, particularly for Southeast Asia and Southern South America (Fig. 1). In these regions, less than 75% of wastewater is treated and large areas are under irrigation with contaminated water.

Location of wastewater (WW) irrigation systems studied in the scientific literature (see Table 1) using either treated wastewater, untreated wastewater, or a mixture of both for agricultural production (symbols) and countries with a high likelihood of irrigation with river water containing untreated wastewater (brown color). Brown-colored countries are countries with a high likelihood of at least 10,000 ha downstream irrigated croplands (DSIC), a return-flow ratio (RFR) of more than 20%, and less than 75% of wastewater treated248. DSICs were defined as irrigated croplands downstream of a city with more than 50,000 inhabitants. The return-flow ratio describes the fraction of wastewater in a surface water body. The brown areas with red stars are the areas where a transition from untreated wastewater to treated wastewater irrigation would be most effective and most likely. The map of brown areas was created using QGIS (v. 3.16.3) based on Figure S6 (supporting online information of Thebo et al.246, published under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Licence).

Historically, the use of untreated wastewater for irrigation has been widespread in developing and emerging economies. However, the advantages of wastewater reuse within circular economy schemes for nutrient and water cycling8, also went along with disadvantages such as the risk of waterborne disease outbreaks9,10. Many nations are now starting to invest in their infrastructure for wastewater collection and treatment to reach SDG 6 “Clean Water and Sanitation”11, explicitly promoting the re-use and recycling of water and nutrients12. However, neither health nor environmental risks have yet been assessed from a holistic “One Health” perspective. The achievement of SDG 6 will induce a shift from irrigation with untreated wastewater in the past to irrigation with wastewater of a higher degree of treatment in the future. The implementation of the most common wastewater treatment schemes, like activated sludge systems, will reduce the load of organic matter, nutrients, and bacteria that is introduced by irrigation water into agricultural fields13. However, many pollutants, like pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), are often only partly removed from wastewater by conventional treatment14,15. Moreover, wastewater treatment plants are identified as hot spots for the spread of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics due to the high densities of bacterial cells, high biological activity, and the simultaneous presence of pollutants16,17,18,19. While the effects of changing the quality of irrigation water from clean water to (treated) wastewater have been analyzed intensively20,21, we are not aware of comprehensive reports on the opposite transition from irrigation with untreated wastewater to irrigation with treated wastewater.

This article reviews the benefits (Chapter 2) and risks (Chapter 3) of wastewater irrigation. Subsequently, water treatment options for reducing health and environmental risks are summarized (Chapter 4). The risk reduction achieved by wastewater treatments is recapitulated in Chapter 5. A particularly novel aspect is the potential side effects of switching from irrigation with water of low-level treatment and relatively high concentrations of organic matter, nutrients, pathogens, and contaminants to irrigation water of a higher treatment level and comparatively lower concentrations of organic matter, nutrients and pathogens, is addressed in Chapter 6. Conventional physico-chemical or activated sludge treatments produce large amounts of sewage sludge, which represent valuable nutrient-rich soil amendments, but bear important pollution risks (Chapter 7). Because advanced water treatment technologies might be not available for resource-limited settings, Chapter 8 sums up alternative and augmenting management options for reducing the health risks of wastewater irrigation. Finally, we draw conclusions for maximizing the benefits of wastewater irrigation while minimizing its risks and identify future research needs (Chapter 9).

Benefits of reuse of wastewater for irrigation

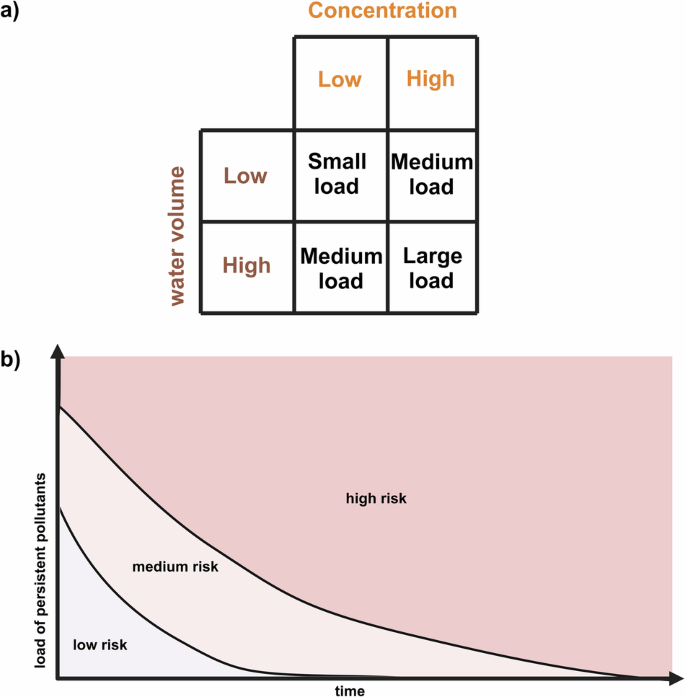

Aside from the apparent benefit of using less freshwater, the use of wastewater allows farmers to grow crops all year-round, especially in arid areas22. The comprehensive benefits of using wastewater for agricultural irrigation are outlined in Table 2. The use of wastewater may even improve yields compared to irrigation with clean water when wastewater irrigation accomplishes macro- and micronutrient demands by the crops. Relevant to the yield increase (as well as other benefits and risks) associated with wastewater irrigation is the load of wastewater ingredients introduced into the fields, not only their concentrations (Fig. 2). When nutrient loads of especially N and P provided by irrigation are large, as for irrigation with untreated wastewater of domestic or agricultural origin23,24, vegetative growth is fostered, increasing productivity of fodder crops. Consequently, irrigation with wastewater can reduce the use of synthetic fertilizers while maintaining the yield, e.g., of rice25 and wheat26. By using nutrient-rich wastewater for irrigation instead of discharging it into surface water, eutrophication of the latter is avoided27,28.

Relationship between irrigation water volume. concentrations of irrigation water constituents, bacteria and ARGs, irrigation time and risk. a “Load” of bacteria, antibiotic resistance genes, organic matter, and pollutants introduced into wastewater-irrigated fields determined as a product of water volume and concentration, and b increase of environmental risk as a function of cumulative time of irrigation and load of persistent pollutants.

Wastewater irrigation has been particularly efficient in retaining N. The N use efficiency was enhanced to 65% and is thus larger than the N use efficiency of <50% of N fertilizers27. Da Fonseca et al.29 estimated that between 179–451 US$ ha−1 can be saved per year for N fertilizers in the first two years when irrigating with secondary treated wastewater containing up to 31.9 mg L−1 N. Besides, the reduction of synthetic N fertilizer usage results in lower emissions of CO2 and N2O, and, due to the high warming potential of N2O, contributes to climate change mitigation30. Additionally, utilizing wastewater for irrigation can reduce energy consumption and CO2 emissions associated with fertilizer production when the nutrient supply with wastewater alleviates fertilizer needs.

Wastewater irrigation also increases the retention of CO2 in wastewater-treated soils by accumulating soil organic matter31,32, mainly due to the greater production of plant (root) biomass. Sánchez–González et al.31 found, for example, that after 40 years of wastewater irrigation in alfalfa-maize crop rotation, the soil organic carbon content increased by a factor of 1.5 and reached a new steady state. The elevated soil organic matter content may be essential for soil health in that it stabilizes soil structure, binds cations, buffers against acidification, provides habitats for microorganisms, and stores nutrients that become available for plant growth upon mineralization33. Also, heavy metals like Cu and Pb22 as well as priority, hydrophobic organic pollutants are well retained by elevated soil organic matter contents34. A loss of soil organic matter by shifting from untreated to treated wastewater irrigation would thus represent a challenge for agriculture and the environment, due to the loss of its many positive functions.

Risks associated with wastewater irrigation

The benefits of wastewater irrigation described above must be weighed against the associated risks. In this section, we analyze first the risks for human health and secondly environmental risks.

Human health risks

Wastewater contains a wide range of potential pathogens for humans, including bacteria, viruses, and parasites35,36,37,38 some of which may make their way to their host through contaminated food – even internalized into tissue – or via groundwater when aquifers are shallow and soils allow their transport. Outbreaks of cholera and typhoid fever were the reason for extensive sanitation efforts in many countries in the last centuries39. The most widespread health hazard of reusing wastewater in agriculture, especially for farmers and their families is the occurrence of helminth and other parasite infections, whereas diarrhea caused by enteric viruses and/or bacteria is a more relevant risk for crop consumers38,40,41,42, and for persons exposed to aerosols produced during water distribution and irrigation43.

Especially among farmers who come into contact with wastewater containing helminth eggs, there is a high incidence of infection by parasitic nematodes44. The incidence of Ascaris sp. infections among farmers and their family members who were exposed to polluted irrigation water was three times higher than that among non-farmers in the control group in a study performed in Ghana44. However, since helminth eggs have also been found on vegetables irrigated with wastewater, such as lettuce, spinach, cilantro, celery, and parsley45, end consumers are also exposed to them. To reduce the risk of helminth infections, guidelines for the reuse of wastewater for irrigation include limits for the number of helminth eggs in irrigation water, e.g. 0.25 eggs or 1 egg per gram of total solids (TS)46,47. Nevertheless, according to Navarro et al.48, it could be more efficient to target higher limits for helminth eggs as these low limits are often not complied with anyway. The risk would be only marginally larger with somewhat higher but achievable values (up to 10 eggs g−1 TS).

The risk of diarrhea is increased in areas using wastewater containing pathogenic bacteria or viruses for irrigation49. Diarrhea is the third leading cause of death in young children worldwide, with about 445,000 children succumbing to this per year50. In addition, repeated episodes of diarrhea and/or worm infections in children may lead to stunting, environmental enteric dysfunction, impaired cognitive functions, and pneumonia51,52,53.

According to Ferrer et al.54, irrigated vegetables and water from wastewater channels in Thailand were seriously contaminated with Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica, both of which also cause diarrhea. The infection risk was high in their tested scenarios and significantly above the risk that was considered acceptable by the WHO47 guidelines. Wastewater-related Giardia infections were also shown in inhabitants of agricultural villages in the Mezquital Valley wastewater irrigation district in Mexico55. Communities in Mexico exposed to wastewater with fecal indicator concentrations in the range of 105 to 107 colony-forming unit (CFU) /100 mL had twice the prevalence of diarrhea compared to those exposed only to freshwater56. This finding not only applies to Mexico but is the case worldwide, as Adegoke et al.57 show in their meta-analysis. For example, the incidence of shigellosis, salmonellosis, typhoid fever, and infectious hepatitis was two to four times higher in kibbutzim communities (Israel) employing spray irrigation with only partially treated wastewater58. Also, a cholera epidemic in Jerusalem was partially caused and spread by wastewater-irrigated vegetables59. However, in Mexico not only the type of wastewater but also the distance to the open canal that is transporting the wastewater determines the prevalence of diarrhea. The risk decreased with the increasing distance of a household to a wastewater channel43. Similarly, the incidence of 600 cases of paratyphoid fever associated with the consumption of raw vegetables was inversely related to the distance of the townships from wastewater-irrigated, contaminated fields in China60.

But not only problems with the gastrointestinal tract can occur. Irrigation with wastewater also increases the risk of enterovirus infections (respiratory tract infections) for farmers and consumers61. Sewage irrigation can also impact the skin. Workers from Hanoi who use wastewater as a source of water and nutrients for agriculture were found to have an increased risk of contracting skin diseases62.

In addition to the health effects due to the transmission of pathogens, wastewater irrigation might also compromise human health by increasing exposure to pollutants. As summarized in a review article by Khalid et al.63, it has been shown that the metal content in soils resulting from irrigation, whether treated or untreated with wastewater, has a significant impact on human health. Pb and Cd pose the greatest risk to human health in connection with wastewater irrigation. A study performed by Lekouch et al.64 in Morocco compared the Pb and Cd content in the hair of children, showing that children whose parents worked as farmers in a region in which irrigation with untreated wastewater was practiced had significantly higher contents than those who were not exposed to untreated wastewater irrigation. Also, Khan et al.65 stated that there is an elevated health risk from Pb, Cd, and Mn when consuming wastewater-irrigated crops. Concerning heavy metal contamination in food, Natasha et al.66 showed that contamination in wastewater (up to 63.6 µg L−1) did not lead to health risks associated with most crops. However, different results from other working groups showed that the actual risk exerted by metals depends mainly on the type of crop and the soil’s physico-chemical properties, which influence the metal transfer factor from the soil to edible parts of plants67,68,69,70. Natasha et al.66 and Zhang et al.71 showed that especially children are at risk of As poisoning of wheat irrigated with untreated wastewater. The risk of As accumulation in rice could be reduced by changing the cultivation method with raised beds and furrows72. Anwar et al.73 reported a potential cancer risk from beans grown after irrigation with municipal wastewater in Pakistan to consumers’ health, especially due to Pb, Cd, and As exposure. Contrarily, the consumption of wastewater-irrigated (secondary and tertiary treated) artichokes was proposed to be safe for both adults and children in terms of heavy metal contamination, according to Gatta et al.74 Based on the estimated daily intake, Gatta et al.74 determined that there are minimal possible health concerns from trace metals and their data support that residents may safely consume artichokes that have been irrigated with treated wastewater.

In addition to metals, pharmaceuticals are contained in wastewater and taken up by crops75,76,77,78,79,80. Consumption of fresh products irrigated with reclaimed wastewater significantly increased concentrations of carbamazepine and its transformation products in human urine81. This illustrates that the exposure of individuals to pharmaceuticals via the wastewater irrigation – soil – plant – human route is possible.

Among the different pharmaceuticals in wastewater, antibiotic agents are of special interest. Especially, hospital wastewater and treated wastewater from antibiotic production facilities may be highly contaminated with antibiotics82,83. While antibiotics released into the environment with wastewater are unlikely to exert acute effects on human health, they likely promote the evolution, selection, and dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes. In numerous reviews, the importance of the environment as a source of antimicrobial resistance determinants and their mobility has been emphasized84,85,86. In this regard, the relative abundance of sul1 resistance genes in wastewater-irrigated soils was found to be two orders of magnitude higher than in non-irrigated soils87 with the resistance genes accumulating along water flow paths within the soil88. Moreover, ARG transfer between even phylogenetically distantly related bacteria may accelerate, as Jechalke et al.89 showed that wastewater irrigation led to an increase in the absolute abundance of the class 1 integron integrase gene, intI1, the quaternary ammonium compound resistance genes, qacE/qacE∆1, streptomycin and tetracycline resistance genes, and the IncP-1 plasmid signature gene, korB, in soils. Uncertainties exist regarding the minimum concentrations of pharmaceuticals for the selection of resistant bacteria in soils, particularly in hot spots like preferential flow paths88. The concentrations of antibiotics and antimicrobials that enter the environment as a result of anthropogenic activities are below the minimum inhibitory concentration (MICs) values of susceptible bacteria90. Here it has to be noticed that even very low concentrations of antibiotics, several hundred-fold below the MIC, can be selective for antibiotic-resistant bacteria in laboratory cultures91 and in biofilms92. Gullberg et al.91 determined minimal selective concentrations (MSC) of 0.1 ng mL−1 for ciprofloxacin and 15 ng mL−1 for tetracycline. The MSC is defined as the concentration of an antimicrobial agent at which the growth rate of a susceptible and a resistant strain is balanced due to the fitness cost of the resistance on one side and the impact of the antibiotic on the other side. Therefore, a growth advantage can be seen for the resistant strain compared to the susceptible strain at concentrations above the MSC. While the range of ciprofloxacin concentrations found in treated wastewater effluents (between 0.27 and 0.30 ng mL−1) as reported by Karnjanapiboonwong et al.93 is higher than the abovementioned MSCs, the concentration of tetracycline in wastewater is lower than the MSC as shown in various studies (e.g., 0.977 ng mL−1 94, or 0.630 ng mL−1 95). So, at first glance, it appears that tetracycline contaminations, unlike ciprofloxacin, do not select for resistant bacteria. However, combinations of several compounds at low concentrations were able to lower the MSCs even further96. In general, antibiotics, pharmaceutical agents, and heavy metals introduced into the soil with wastewater can select for resistances via co-selection mechanisms97 or enhance the conjugative transfer of resistance genes carried by plasmids98,99,100,101,102,103. Thus, Song et al.104 showed that exposure of soil bacteria towards Cu and Zn caused a stronger selection of tetracycline resistance than exposure to tetracyclines itself. A co-selection of antibiotic resistance by quaternary ammonium compound disinfectants in the environment (as documented in clinical settings) has also been proposed, but more research is needed to underpin the relevance of disinfectants for the selection and spread of antibiotic resistance in the environment105. Zeng et al.106 have recently shown that manure application increased the co-selection effect of the antibiotic sulfamethoxazole and the quaternary ammonium disinfectant benzalkonium on the soil resistome (i.e., all resistance genes of the bacterial community). In addition, it has been recently shown that non-antibiotic pharmaceuticals can have antibiotic side effects and may, therefore, contribute to the selective effects of antibiotics107,108.

Resistant environmental bacteria and resistance genes reach humans via direct exposure (e.g., occupational exposure of field workers or recreational activities like water sports) or the food chain. The most important exposure pathway in the food chain in the case of wastewater irrigation is plants, especially fresh produce. Several recent studies indicated that the resistome of plants is shaped by the plant species, the soil type, and the antibiotics present in the soil and irrigation water77,92,109,110,111. The effects of antibiotics and disinfectants in plant tissues on the selection of resistant plant-associated bacteria and the transfer of ARGs are largely unexplored.

Environmental risks

A wide range of chemical pollutants is introduced into wastewater-irrigated fields112,113. An immediate increase in contents of soluble salts originating from detergents, cleaning material, and other sources112 in wastewater-irrigated soils is common114, but can be counterbalanced by overirrigation. If irrigation is insufficient, salts can accumulate in the rooting zone, resulting in salinization of soil upon wastewater irrigation115,116. Potential consequences are acute toxic effects of mainly chloride (Cl–) and sodium (Na+) on most crop varieties as well as osmotic stress. Ganjegunte et al.117 showed in a soil column experiment that soils irrigated with salt-rich wastewater contained less soil organic matter than freshwater-irrigated soils. They postulated that salts introduced into the wastewater-irrigated soil inhibited plant growth as well as soil bacteria, resulting in fewer biomass inputs and buildup and ultimately less organic soil matter than in freshwater-irrigated soils. Surfactants and Na+ can exacerbate the dispersing of soil particles, leading to the deterioration of soil structure, pore blockage, and eventual reduction of soil permeability and waterlogging118. The negative effects of salinization can be minimized by elevated organic matter contents that stabilize the aggregates119 or by wastewater treatment, though only with expensive processes such as reverse osmosis120 (see next section). In addition, simple dilution with water of low-salt content can solve the problem, thus posing avenues for mitigation when wastewater quality changes.

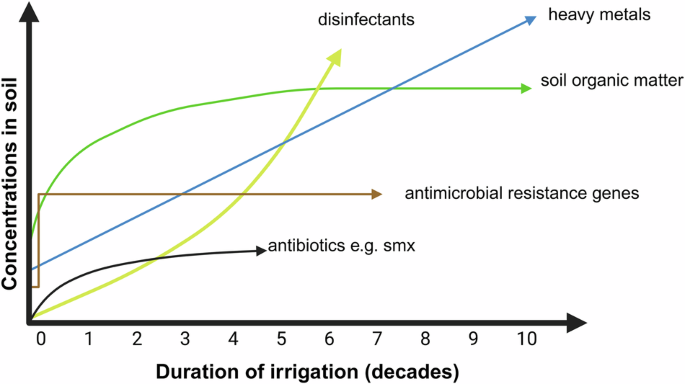

Heavy metals contained in the wastewater tend to accumulate linearly over time in the irrigated soil112,121,122,123. Apart from the load of metals introduced into the fields (Fig. 2), the accumulation rate of metals (slope in Fig. 3) depends on the binding and retention of the metals in the soil. The binding strength and the retention of metals in soils in turn are controlled by soil pH, soil texture (clay content), soil organic matter content, and redox regime (e.g.,124) and are further metal-specific. Overall, metal binding strength and retention tend to decrease with decreasing pH, clay content, and soil organic matter content.

Schematic representation of the accumulation of soil organic matter31, heavy metals121, disinfectants129, antibiotics (e.g. sulfamethoxazole (SMX)87, and antimicrobial resistance genes87 in soils over time during irrigation with untreated wastewater in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico.

Mahjoub et al.125 reported that wastewater contains estrogen-like and dioxin-like organic contaminants and that estrogen-like contaminants were transferred to irrigated soil, leading to concentrations of 0.05 ng E2-EQ g−1 (estradiol equivalent). The fungicide hexachlorobenzene, the plasticizer Bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and other compounds were recently found in soils irrigated with treated wastewater from the wastewater treatment plant of the Penn State University in Pennsylvania at higher concentrations compared to non-irrigated fields126.

Several studies provided evidence of a wide range of pharmaceuticals, surfactants, and disinfectants present in wastewater used for irrigation127,128,129. Sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, carbamazepine, and trimethoprim accumulated in soil with increasing duration of irrigation87, with concentrations reaching a constant level after several decades of irrigation (Fig. 3). Sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin that enter irrigated soils with wastewater accumulated mainly along water flow paths88. Durán-Alvarez et al.130 analyzed acidic pharmaceuticals, carbamazepine, and potential endocrine disruptors in soils irrigated with untreated wastewater and found that carbamazepine accumulated in soil while all other compounds dissipated, so that their concentrations declined over time. Gibson et al.131 also described that carbamazepine (3.5–7.0 mg kg−1) and triclosan (5.7–16.7 mg kg−1) accumulated in wastewater-irrigated soils after 90 years of wastewater irrigation. The phenomenon that pharmaceuticals, which are in principle biodegradable, accumulate in soil over extended periods is closely linked to the “aging” of their binding forms and the process of sequestration132.

Accumulated PPCPs in soil can further be taken up by plants, resulting in the contamination of the food chain with possible consequences for human health (see Chapter 2)133,134.

Large amounts of plastic, especially in the size of microplastic (1 µm–5 mm) are present in untreated wastewater, originating from care products, surface runoff, atmospheric deposition, washing machine effluents, and inadequate end-of-life strategies135,136. Likewise, improper disposal of plastic items in toilets and sewer channels leads to plastic in untreated wastewater. Plastic concentrations found in untreated wastewater range from 1000 to 627,000 items m-3, and exceed by far the concentrations in lakes (up to 34,000 items m-3), rivers (up to 67,500 items m-3), ground- (up to 80,000 items m-3 near landfills) or treated wastewaters (0–125,000 items m-3)135,137,138,139. Most of these items are hardly degradable nor can they easily be leached out of the soil (e.g.,140). Hence, their accumulation in the soil will depend on the loads and bear a larger risk as irrigation with polluted water continues over time. Although >98% of microplastics can be removed from water during its treatment, because of the enormous volume of wastewater generated daily, a significant amount of microplastics still ends up in the environment141 and accumulates in the irrigated soils142,143,144. Microplastics in extremely high concentrations can disrupt the activity of microbial decomposers and nutrient cycles, interfere with plant growth and development, hinder organisms’ digestive apparatus and plant root systems, and may act as a vector for hazardous substances and ARGs36,145. Fortunately, such extreme concentrations are frequently not yet reached140.

Figure 3 summarizes the different patterns of the accumulation of pollutants. If their input load is rather constant, heavy metals increase linearly121, because they are not degraded in soils. Antibiotics show an asymptotic accumulation, either because of the start of inputs at a certain point of time in the past or because of equilibrium between inputs on the one hand and degradation and/or transformation on the other hand87. An exponential increase with increasing time of irrigation as observed for disinfectants might be caused by either historically large inputs that declined over time or by increasingly strong sequestration of pollutants in soils129. Moreover, the rate of pollutant accumulation in soils depends on the pollutant load introduced into the fields, thus the product of irrigation water volume and pollutant concentration in the wastewater (Fig. 2), which in turn depends also on the level of wastewater treatment, as will be shown in the next section (Fig. 4). The accumulation of pollutants in soils further depends on their persistence, which is mainly determined by their recalcitrance against biological breakdown, by the presence and activity of degrading organisms in soil and by their mobility in soil, i.e., by their transfer into other compartments, as plants or the ground- or surface water.

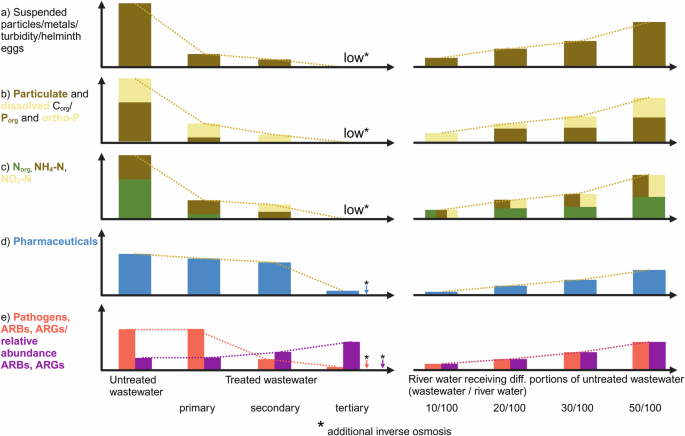

Impact of selected wastewater treatment levels on different water quality parameters (left) and the effect of mixing untreated wastewater with unpolluted surface water (right). a Suspended particles, metals, turbidity, helminth eggs, b particulate and dissolved organic C (Corg), organic P (Porg) and ortho-P, c organic N, NH4-N, and nitrate-N, d pharmaceuticals, e pathogens, and concentrations as well as relative abundance of antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARBs) and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs).

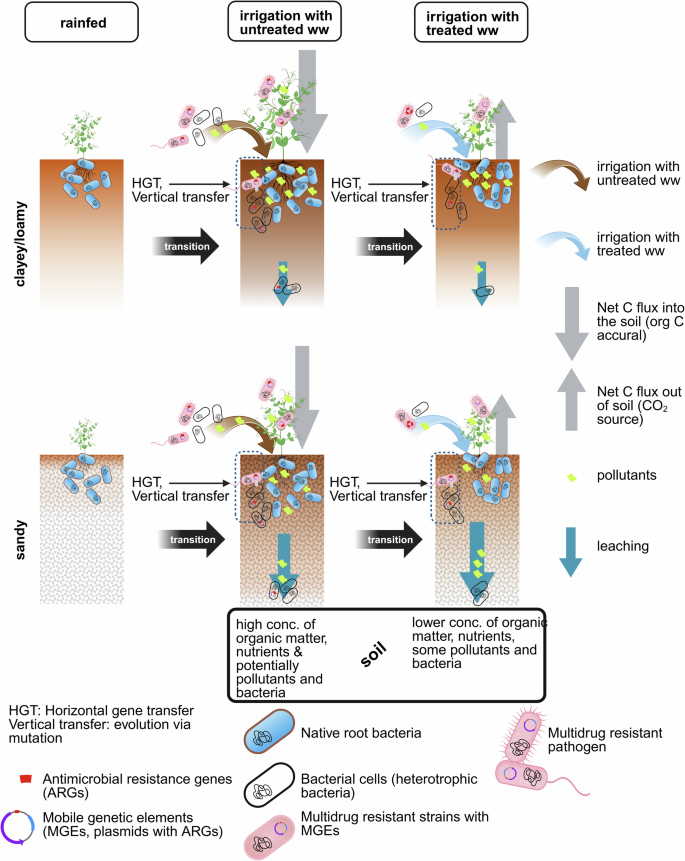

Figure 5 illustrates that the soil characteristics influence the accumulation and retention of pollutants as well. Due to the larger surface area of soil particles, and larger reactivity of fine soil particles such as clay minerals and (hydr)oxides compared to coarse quartz sand grains, clayey soils likely experience a stronger accumulation compared to sandy soils. Larger contents of soil organic matter contribute to sorb and chelate heavy metals and bind organic pollutants. Circumneutral to slightly alkaline pH values decrease the solubility of many metals and reduce their bioavailability (e.g.,124).

Schematic change of crop growth as well as inputs, abundance/concentrations, plant uptake and leaching of bacteria, antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs), and pollutants when moving from rainfed agriculture to irrigation with untreated or low-quality water to irrigation with treated water of higher quality as influenced by soil type (sandy versus clayey/loamy soil). Clayey and loamy soils with typically large filter and buffer capacities can build up more soil organic matter (darker color), and retain larger amounts of pollutants as well as nutrients, allowing large increases in crop yields under irrigation. Sandy soils with typically smaller filter and buffer capacities tend to accumulate less organic matter, retain fewer pollutants as well as nutrients, and provide smaller increases in crop yields under irrigation than clayey/loamy soils. During the transition from irrigation with untreated wastewater or low-quality water to irrigation with treated water of higher quality with smaller concentrations of organic matter and nutrients (right half of figure), crop yields and soil organic matter contents decline leading to a release of accumulated pollutants. Yield reductions and release of pollutants are likely larger for sandy soils with small filter and buffer capacities than for clayey and loamy soils.

Summarizing, wastewater irrigation bears many adverse effects on human and environmental health. Their magnitude depends on the type, pathogenicity, and survival of organisms contained in wastewater in the environment as well as the toxicity, persistence, and loads of pollutants released into agricultural fields. Water treatment prior to its use in agriculture aims at minimizing these risks.

Treatment of water for irrigation

Treatment of wastewater prior to its use for irrigation is recommended to reduce health and environmental risks8. Wastewater treatment is a broad term that indicates any form of treatment without considering the level or removal of water constituents, yielding gradients in resulting water quality (Fig. 4). Wastewater typically undergoes pre-treatment to get rid of gross solids, sands, debris, and oil that could interfere with later stages of treatment. The goal of the primary treatment is to settle and eliminate organic and inorganic suspended particles (Fig. 4a). Septic tanks, Imhoff tanks, and primary settlers are most used in this step. Since heavy metals tend to sorb to particles, primary treatment can already lead to a reduction of their concentrations in wastewater (Fig. 4a). Secondary treatment technologies break down and remove soluble biodegradable organics by biological processes (aerobic or anaerobic) (Fig. 4b). Sorption of heavy metals and other pollutants to flocs can further reduce their concentrations in wastewater (see following Chapter 7). Organic N is removed together with the organic particles, yet a part of the organic N compounds is mineralized to NH4-N and further oxidized to NO3-N in aerobic treatment systems (Fig. 4c). Aerated lagoons, activated sludge, trickling filters, oxidation ditches, and artificial wetlands are examples of common secondary treatments. Tertiary and fourth treatment stages include the removal of microbes, hazardous substances, residual suspended particles, and nutrients before the water is used for crop irrigation or discharged into the environment (Fig. 4). This step can include filtration with activated carbon, membrane filtration, reverse osmosis, and infiltration/percolation as well as disinfection with chlorination (most common), ozonation or ultraviolet (UV) irradiation.

The primary (mechanical) treatment has a negligible role in the removal of ARGs from wastewater (Fig. 4e). A reduction of only 0.15-1.75 orders of magnitude was reported. The secondary (biological) treatment in activated sludge tanks is also not effectively removing ARGs. In contrast, the high nutrient content and bacterial concentrations are enhanced, especially triggered by the co-occurrence of pollutants, and horizontal gene transfer of ARGs. Within the biological treatment system, ARGs partially attach to activated sludge flocs, in consequence up to 38% of the ARGs are removed in the effluent by sedimentation in the secondary sedimentation tanks. Which in consequence leads to an accumulation of ARGs in surplus sludge. Advanced treatments have different effects. For UV disinfection in doses routinely applied in WWTPs only minor to no effects concerning ARG reduction were reported. For chlorination and chemical oxidations, it is even reported that they increase the release of ARGs through the release of DNA from bursting bacterial cells. In general, the release of treated wastewater into rivers increases the content of ARGs in river water by approximately two log scales146.

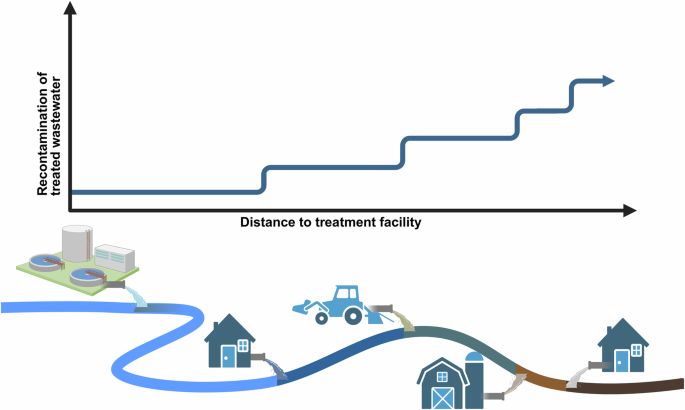

Tertiary treatment and disinfection stages are not often used in low-income countries147. Countries with larger gross domestic products typically treat a larger portion of their wastewater with more sophisticated treatment technologies148,149. The high cost of advanced treatment methods often prevents their application in regions with limited financial resources, leading to a reliance on lower levels of treatment or even untreated wastewater for irrigation. An overview of the relative costs can be found in Table 3. The type of treatment applied, however, determines the final characteristics of the wastewater used for crop irrigation. Treatment typically reduces not only pathogens but also the nutrient and organic carbon contents of the water. While this is advantageous to protect surface water bodies, these nutrients are lacking when the water is subsequently used for irrigation of agricultural fields. Moreover, any discharge into the river results in the mixing of treated and either clean or polluted water (Fig. 6), i.e., in variable water qualities at different irrigated fields. Leveraging the full beneficial potential of wastewater treatment for irrigation requires the prevention of re-contamination of treated water or the re-growth of harmful organisms like bacteria. Espira et al.150 assumed that re-contamination was the reason for the increasing risk of bacterial infection after the passage of treated wastewater through a sentinel village in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico.

Recontamination of treated wastewater following its discharge into rivers and irrigation channels, when the coverage with treatment is incomplete.

A complete removal of all hazardous organisms, ARGs, and pollutants by water treatment often cannot be achieved14,151,152,153. Therefore, the WHO guidelines for the safe use of wastewater in agriculture explicitly recommend adapting the degree of treatment to the type of crop to minimize the health and environmental risks47. Considering the soil’s capacity to filter and immobilize pollutants could help decrease risks further.

Reduction of risks by increasing the level of wastewater treatment for irrigation

Moving from irrigation with low-quality (untreated) wastewater to irrigation with higher-quality (treated or reclaimed) wastewater reduces health and environmental risks. In the following, we summarize how different kinds of treatments reduce distinct indicators of health and environmental risks.

According to Ben Ayed et al.154, in Tunisia 496 and 960 helminth eggs per liter in untreated wastewater diminished to 0 and 52 eggs per liter after stabilization ponds or activated sludge treatment, respectively. A decrease in the number of helminth eggs from 30 and 46 eggs per liter to 0-1 egg per liter by constructed wetlands, stabilization ponds and conventional activated sludge treatments was also described by Sharafi et al.155. López et al.156 showed a reduction of Enterococcus spp. by 2.6-log units and a reduction of Pseudomonas spp. by 1.5-log units after primary treatment, which depending on the number of bacteria in untreated wastewater could allow the safe irrigation of e.g. fodder crops.

According to a review by Wang et al.157, wastewater treatment typically achieves a 53–78% removal of antibiotics, ARGs (min. two orders of magnitude in the city of Bonn158), and 99% of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Nevertheless, residues of antibiotics, disinfectants, ARGs, and resistant bacteria are still released with the treatment plant effluent into the environment153,157. Munir et al.159 showed that disinfection processes such as chlorination and UV exposure did not contribute to a further significant reduction of ARGs and antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Filtration should remove 100% of the bacteria, otherwise, the presence of nutrients can lead to regrowth, which might prevent the irrigation of e.g. fresh produce with the treated water.

Due to the high density of different bacteria, their high activity, and reproduction rates in combination with their exposure to antibiotics and other pollutants, wastewater treatment can facilitate the spread of antibiotic resistance. High antimicrobial resistance transfer rates in activated sludge can be assumed from the high abundance of ARGs and mobile genetic elements. This reflects that the resistome of activated sludge is rich in ARGs harbored by mobile genetic elements such as transposons and integrons, which are mainly located on plasmids160,161. Resistance genes for antibiotics, disinfectants, and heavy metals are often co-located in genetic units (chromosomal DNA or plasmids) in bacterial cells162. The presence of at least one of those pollutants can select for resistant bacteria during wastewater and sludge treatment163,164. Different groups of plasmids were found to be carriers of the ARG pool. It was shown that plasmids contributed significantly to the transmission of resistances among environmental and clinical strains165,166. Li et al.167 demonstrated that broad host range IncP-1 plasmids persisted in a sewage sludge bacterial community under different O2 and nutrient levels. They caused fitness effects when present in different members of complex bacterial communities including Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas. Host tracking in metagenomic studies showed that a variety of bacteria in the wastewater treatment effluent contained multidrug-resistance plasmids. This confirmed that wastewater treatment plants are hotspots of ARG exchange160. Bacteria harboring ARGs that are released with treated wastewater into soils that have been irrigated with untreated wastewater for a long period of time might be exposed not only to the residual pollutants in the treated wastewater but also to pollutants that are released from these soils.

Choubert et al.168 demonstrated that the metals Pb and Cd, which Khalid et al.63 identified as particularly hazardous, are reduced by an average of approximately 75% (Pb) and 50% (Cd) across nine secondary treatments. However, it is noteworthy that there were also instances where wastewater treatment plants removed less than approximately 10% of these elements. The reduction of metal concentrations in wastewater through treatment mitigates the likelihood of human exposure to these metals through exposure to contaminated water, which reduces the risk of chronic diseases and acute health problems.

However, while metals are typically removed quite efficiently, conventional wastewater treatment (i.e., primary and secondary activated sludge) achieves only partial reductions of several emerging contaminants. For example, the concentration of diclofenac was only marginally reduced (0.6%) by a conventional activated sludge treatment. The same applied to carbamazepine, sulphapyridine, and venlafaxine169. Östman et al.170 calculated loads of benzotriazole, methyl benzotriazole, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, chlorhexidine, quaternary ammonium compounds, and fluconazole in the order of a few to more than 100 g day−1 to be released from three different Swedish wastewater treatment plants with biological and chemical treatment processes. Moreover, Aymerich et al.169 described that some transformation products (Carbamazepine > 2-Hydroxycarbamazepine and Venlafaxine > N-Desmethylvenlafaxine) of the parent pharmaceutical molecules were generated during the wastewater treatment process. These products may have a similar or different harmful effect as the parent substances. In contrast, when carbamazepine was directly released into river water, the transformation products were not formed and carbamazepine contents were reduced169. The discharged treated wastewater may also contain novel chloro-dimethyl-benzotriazole compounds, which are possible transformation products of the chlorine disinfection process at the wastewater treatment plant126. So organic micropollutants can still end up in the water and soil despite most types of wastewater treatment, thus feigning a false absence of risk in the use of treated wastewater. If water treatment fails to eliminate these compounds, then also no mitigation from improvements in wastewater quality can be expected.

Large plastic pieces are removed in wastewater treatment plants by bar screens, while the evidence about the fate of microplastics is dependent on the plastic loads of the incoming water as well as on treatment technology. On the one hand, some studies showed high removal efficiencies of up to 99.7% for microplastics by primary followed by secondary treatment171. On the other hand, still high amounts of plastics (99 items L−1) were found in wastewater after primary treatment172. The fraction not removed during the treatment process is probably dominated by small plastics (nanoplastics 1–100 nm), and will end up in river systems, making wastewater treatment plants one of the most important land-based microplastic sources for aquatic systems173,174,175,176 and for soil when the treated wastewater is used for irrigation142,143,144. Depending on the electrochemical conditions, nano and eventually also very small microplastics may migrate and transport viruses and ARGs177.

Overall, it can be expected that implementation of wastewater treatment will reduce the introduction of harmful organisms, ARGs, and pollutants into the irrigated agricultural fields, if re-contamination of water in rivers and irrigation channels can be prevented. However, the change from long-term irrigation with highly contaminated water to irrigation with improved water quality could lead to the release of pollutants that accumulated in the soil over time in the past, which is addressed in the next chapter.

Transition from long-term irrigation with low-quality water to irrigation with improved-quality water

A holistic assessment of the consequences of the implementation of wastewater treatment in long-established wastewater irrigation schemes must take into account the remaining nutrients and contaminants in the effluents as well as the accumulation of pollutants, pathogens, and resistance genes in soils during preceding irrigation with lower quality water described in Chapter 3.

Although salts and especially Na+ are found in the influent and effluent of wastewater treatment plants, the sodium percentage in the effluent can be higher than in the influent, as shown for a plant in India by Gautam et al.178. Chávez et al.179 showed that Ca2+ was not removed, Na+ was removed by 14% and K+ was increased by 167% in partially treated wastewater compared to untreated wastewater. Thus, the effects of soil salinization mentioned above could even be increased when irrigating with treated wastewater (if no reverse osmosis or similar cost-intensive methods are used). The applied water volume needs to be adjusted to wash soluble salts out of the rooting zone, limiting water-efficient irrigation techniques such as drip irrigation.

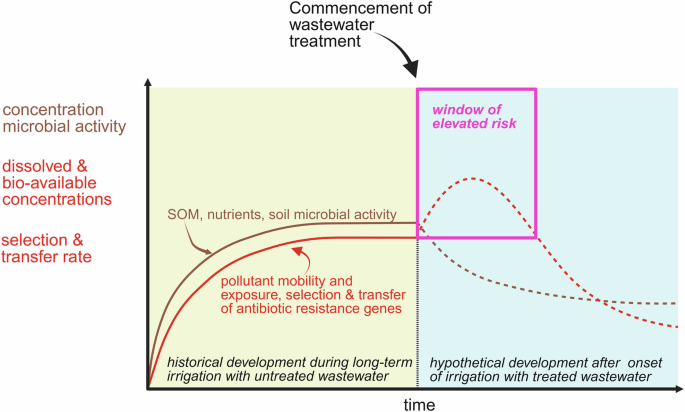

As outlined in Fig. 5, pollutant concentrations can be “buffered” by soils or even an additional mobilization might occur after the change in irrigation water quality. As a consequence of re-contamination of treated wastewater or “buffering” as well as mobilization of legacy pollutants, the reduction of the exposure of humans and related health risks might be smaller than expected, similar or even increase after the introduction of wastewater treatment, although the quality of the water used for irrigation has been improved.

Recently, Ziegler Rivera et al.180 showed in batch and column experiments that the mobility of potentially toxic elements (e.g., As, Cd) in soils might be increased by switching from irrigation with untreated water to irrigation with treated wastewater. They also found that Zn, Pb, and Cd mobilization was even stronger when chlorination of wastewater was performed. One of the factors contributing to the release of Cr and Cd in soils was the higher salinity in their experiments mimicking treated wastewater irrigation.

There is only sparse information on the degree and rates at which pharmaceuticals and other pollutants that have accumulated in soils due to irrigation with untreated wastewater can be released when switching from irrigation with untreated wastewater to irrigation with treated wastewater. Carrillo et al.181 showed that sulfamethoxazole slowly desorbed from Phaeozems and Leptosols with a long history of irrigation with untreated wastewater when these soils came into contact with treated wastewater. In contrast, no desorption was observed in Vertisols181. The fact that many organic pollutants can nowadays still be found in groundwater and surface waters several years after the end of their production and application indicates that the pollutants can slowly return from the soil matrix into soil water and drainage. A prominent example illustrating the enduring release of pharmaceuticals from contaminated wastewater-irrigated soils is the “Rieselfelder” around Berlin. There, wastewater was treated by infiltration into the sandy soils (soil-aquifer treatment) from the late 19th century until the early 1990s. Although the infiltration of sewage was stopped 30 years ago, the “Rieselfelder” continues to act as a source for pharmaceuticals in groundwater182,183. Mordechay et al.184 showed that wheat grown under rainfed conditions took up carbamazepine introduced into the soil with treated wastewater in the past, illustrating the storage and subsequent release of this component in soil.

The release of pollutants that have accumulated over time in the past in irrigated soils (see Figs. 3 and 5) might occur since the organic matter loads as well as the total concentrations and relative proportions of soluble ions in the treated wastewater differ from those of the untreated wastewater. As illustrated in Fig. 5 a reduction of nutrient inputs will reduce biomass yields if not compensated by the application of fertilizer. Since the organic matter content of soils depends on organic matter inputs, a reduction of organic matter loads introduced with wastewater and reduced biomass production might lead to a decrease of soil organic matter contents (SOM), which is likely faster and more pronounced for sandy soils than for clayey soils (Fig. 5). Because SOM is an important sorbent of pollutants, decreasing organic matter contents could in turn reduce the binding of pollutants in soils and promote the mobilization of legacy pollutants, which can then be leached to groundwater or taken up by crops (Fig. 5). This reduction of binding and mobilization of pollutants is probably larger for sandy soils than for clayey soils due to the smaller sorption and buffering capacity of the mineral phase of sandy soils. Hence, overall, the implementation of wastewater treatment could lead to a transient disequilibrium of the steady state condition established previously during long-term irrigation with untreated wastewater before a new steady state equilibrium is reached. As a consequence, the implementation of wastewater treatment might open a window of transiently elevated risk (Fig. 7).

“Window of elevated risk” opening during the transition from irrigation with untreated wastewater/low-quality water with high concentrations of organic matter, nutrients, and pollutants to irrigation with treated wastewater or higher-quality water.

Sewage sludge: an implicit byproduct of water treatment needing attention

Many of the contaminants, like heavy metals and pharmaceuticals, but also plastics that are eliminated from the wastewater during the treatment process accumulate in the sewage sludge135,161. Metals that enter the treatment plant via surface runoff or domestic wastewater are partitioned differently between the solid phase, i.e. the sludge, and the liquid phase, i.e. the effluent. Karvelas et al.185 showed that Cu and Mn accumulate to almost 80% in the sewage sludge, as do 40% of Cr, Ni, Pb, Fe, and Cd. Early on in 1983, Petrasek et al.186 showed that it is mainly the distribution coefficient Log KOW that explains whether organic pollutants accumulate in effluent or sewage sludge if they are not transformed, degraded, or lost to the atmosphere by outgassing during treatment. Thus, most of the polychlorinated biphenyls, phenols, phthalates, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons investigated were bound to the sewage sludge. The only exceptions were lindanes, bis-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalates, phenol, and di-n-butyl phthalates, which were present in higher quantities in the effluent. Katsoyiannis and Samara187 investigated 26 persistent organic pollutants in a similar study and showed that a significant fraction of organic pollutants accumulated in sewage sludge compared to sewage plant effluents. These ranged from a fraction of 39% accumulating in sludge for β-hexachlorocyclohexane to a fraction of 98% p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (metabolite and degradation product of the organochlorine pesticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane). Golet et al.188 reported concentrations of ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin in sewage sludges ranging from 1.40 to 2.42 mg kg−1 from different treatment plants. Göbel et al.189 analyzed activated sludge revealing concentrations of sulfapyridine, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, azithromycin, and clarithromycin between 28 and 68 μg kg−1. Also, antimicrobial quaternary ammonium compounds have consistently been demonstrated to enrich and persist in digested sewage sludges at mg kg−1 level161,170,190.

As many wastewater pollutants end up in sewage sludge during the treatment, the overall reduction of environmental risks that can be achieved by conventional activated sludge wastewater treatment depends to a large degree on the handling and disposal of sludge. If the sludge is used for fertilizing agricultural land, and to compensate for potential reductions of nutrient inputs and SOM losses, these pollutants will reach soils. The question then arises whether the addition of pollutants with sludge as a single but large pulse every 3 to 5 years, as generally used for solid organic amendments as biosolids, is preferable to the continuous addition of small amounts by each irrigation with untreated wastewater. Critical is therefore the degradation and detoxification of pollutants during sludge treatment. At least for metals, however, such degradation does not occur. Thus, advanced treatment for the removal of metals might become necessary if an application of sludge to agricultural land is envisioned.

Not only pollutants, but also nutrients and organic matter that are removed from wastewater during the treatment process are retained in sewage sludge as a byproduct of several water treatment types, like activated sludge treatment. Hence, the application of sewage sludge (or “biosolids”) to agricultural land is a well-established practice to close nutrient cycles and improve soil fertility191. A prominent and well-studied example is the recycling of P via land application of sewage sludge (ash)192,193,194,195, which can help, therefore, to mitigate future shortcomings in this essential nutrient. P recycling is important because it is an essential nutrient for all living organisms with limited availability. Conventional Pfertilizers are made from phosphate rock, which is a sedimentary rock rich in P-containing minerals as apatites. The natural reserves of these rocks are limited. Scientists have warned that in some decades, the limited availability of P rock will jeopardize agricultural production. The present rate of mining would result in a full depletion of the P rock deposits in about 370 years. This time will most likely be shorter than 370 years because both output and demand are currently rising196. Thus, P as a scarce resource must be recycled to close the P cycle197 and to avoid inputs of some specific co-contaminants like uranium from low-quality P rocks into soils198,199.

The fate of C and nutrients applied with the sludge to soils significantly depends on sludge treatment. In wastewater treatment plants with secondary biological activated sludge treatment procedures, about 90% of the organic carbon is removed from the wastewater200. This organic carbon is then either retained in the sewage sludge or released into the atmosphere as CO2. In a study by Gascó et al.201, the sludge’s organic carbon content reached up to 77 w/w%.

When sludge is applied to agricultural land, most of its organic matter content is mineralized rapidly (50% of carbon in 60 days202) due to enhanced microbial activity in the soil. The mineralization of organic matter after land application depends, to a large degree, on the treatment of the sludge. Badza et al.203 concluded that the addition of aerobically treated sludge leads to a higher loss of organic carbon released as CO2 per kg soil than the addition of anaerobic sludge. The land application of anaerobically-treated sludge, on the other hand, promotes the mineralization of N-containing organic compounds in the soil203. In general, the total protein content is higher in sewage sludge than in wastewater200, indicating rather low stability in soil. Therefore, while the land application of sludge allows in principle to maintain or even to increase SOM stocks, it has to be kept in mind that the sludge-derived organic matter is to a large degree mineralized fast, which might also trigger additional mineralization of native SOM (“priming effect”). Indeed, Adany and Tambone204 showed that the addition of 1 t ha−1 of sludge over a period of 10 years was insufficient to cause a significant increase in SOM contents.

Balancing benefits and risks of the implementation of water treatment for wastewater irrigation

Depending on the level of treatment, reclaimed water allows the production of a wider range of crops, including fresh produce with the exception of leafy vegetables205, which maximizes the benefit of increased productivity and yield. Thus, using tertiary treated wastewater to grow fresh produce not only helps tackle problems of drought and freshwater scarcity, but also enhances sustainable crop production and agricultural practices, resulting in increased yield and enhanced nutritional quality in crops and fresh produce206,207, supporting the achievement of SDG 2. Contrary to Mordechay et al.205, Manasfi et al.208 showed a de minimis risk to human health associated with eating raw leafy green vegetables irrigated with effluents from conventional secondary treatment with three successive stabilization ponds. The possibility of selling fresh produce of high value instead of crops like fodder or grains can further increase farmers’ income while maintaining the same acreage. Yet, the production of fresh produce might require increased know-how, labor, and investment in pest control compared to e.g. the production of fodder crops or grains. Especially if previous irrigation with untreated wastewater has led to a strong accumulation of pollutants in soils so that a “window of increased risk” is conceivable, monitoring the quality of produced plants is advisable until a new equilibration of the irrigation system is reached.

While the positive effect of wastewater irrigation on economic yields and nutrition can be maximized by the treatment of wastewater before its use in agriculture, other benefits might be at least partly compromised. An important task of wastewater treatment is the removal of P from wastewater to prevent eutrophication of surface water209. Preventing eutrophication of water bodies is also the reason why N compounds are converted to N2 in wastewater treatment plants210 and thus released into the atmosphere, resulting in lower N concentrations in treated wastewater. Crop yields may decline if alternative fertilizers are not used to make up for the decreased N and P supply of treated wastewater to irrigated soils (Fig. 5). If synthetic N fertilizers are employed to prevent yield decline, the reduction of CO2 emissions achieved by wastewater irrigation is jeopardized by N fertilizer production. Decreasing yields would imply a decreasing return of crop residues to soils. Given that irrigated soils accumulate large quantities of SOM over time as a consequence of high biomass yields and inputs as well as direct inputs of organic matter with irrigation water, a switch from irrigation with untreated to irrigation with treated wastewater can result in decreasing SOM stocks. Declining contents of SOM might in turn affect soil structure, water holding capacities and infiltration rates and thus amplify the decrease in productivity211. Hence, as a consequence of declining soil organic matter stocks, the implementation of wastewater treatment might turn irrigated soils from CO2 sinks into CO2 sources until a new equilibrium SOM stock is reached (Fig. 5). The reduction of SOM contents increases the risk of fostering other soil degradation processes, like erosion (by water and wind), loss of biodiversity, and lower retention or even release of pollutants212,213.

The fact that maximizing the level of water treatment for minimizing health and environmental risks can jeopardize the benefits of wastewater irrigation. This calls for a flexible, integrated, and customized choice of suitable water treatment technologies in combination with additional strategies for risk mitigation considering the irrigated crop, the history of irrigation as well as the filter and buffer capacities of soils.

Integrated approaches to wastewater management for irrigation: Combining water treatment and augmenting strategies for risk control in resource-limited settings

Advanced wastewater treatment for mitigating risks is not always a viable option due to structural or financial constraints (see Table 3). The integration of treatment with augmenting strategies for risk control can effectively address the challenges encountered in resource-limited settings if advanced water treatment technologies cannot be implemented. Protection against wastewater hazards can be provided at all points along the water-food chain from the source of the wastewater to the treatment plant, to the farm, from the retailer to the consumer. This is known as the multiple-barrier approach47,214. In an alternative approach to the maximal treatment of wastewater, risks can be mitigated by the implementation of drip or flood and furrow irrigation techniques. When utilizing sprinklers, their height can be reduced to minimize the potential for splashing. Yet, sprinklers will enhance the dissemination of potential pathogens by aerosols, so it must be considered carefully depending on the crop type and irrigation water quality. Furthermore, the irrigation process can be halted a few days to weeks (depending on the crop) before the harvest. It is also crucial to emphasize the importance of avoiding direct contact with wastewater215,216 and to refrain from washing the products with irrigation water, both during and after the harvesting process. In this way, the risk of helminth infection would decrease when implementing crop restrictions and better washing practices, even with higher limit values for helminth eggs in irrigation water48. At the point of sale and subsequently, at the end consumer, the products should be washed with either vinegar (an expensive product and therefore often used in insufficient quantities), salty water (readily available), or a potassium permanganate solution (also readily available, but potentially harmful depending on its concentration)217. Transportation and storage of the products at low temperatures prevent pathogen proliferation on the products214,218. The enhancement of general sanitary conditions can also serve to mitigate the risk of health hazards, both for the end consumer and for the marketer or restaurant. Good sanitary conditions particularly prevent the cross-contamination of food214.

Conclusions and research needs

The reuse of wastewater for irrigation in agriculture is widespread and is expected to expand further due to rising pressures on regional water resources driven by climate change and population growth, especially in urban agglomerations. Investments in wastewater collection and treatment to reach SDG 6 “Clean Water and Sanitation” will help to mitigate health and environmental risks associated with wastewater irrigation.

Leveraging the full beneficial potential of wastewater treatment for irrigation requires the minimization of re-contamination and re-growth of harmful organisms in rivers used for irrigation and irrigation channels. The opening of “windows of elevated risks” for human and environmental health after the implementation of water treatment in long-established irrigation systems should be monitored to allow countermeasures. The probability of the “opening” and the “size” of potential “windows of elevated risk” after the implementation of wastewater treatment depends on i) the magnitude of water quality change (i.e. untreated to tertiary treated or untreated to primary treated), ii) irrigated crops, iii) the cumulative load of pollutants that soils have accumulated during past irrigation, and iv) soil properties.

Augmenting risk management measures within a “multi-barrier” approach can help to maximize the benefits of wastewater irrigation while minimizing the potential risks associated with the transition from irrigation using untreated wastewater or heavily polluted surface water to the utilization of treated wastewater. A holistic and sustainable management of wastewater and wastewater irrigated soils within the interconnected cycles of water, carbon, nutrients, and other elements, requires an integrated assessment of multiple goals in addition to SDG 6 “Clean water and sanitation”. These are SDGs 1 “No Poverty” (increased income), 2 “Zero Hunger” (improved food production), 11 “Sustainable Cities” (link cities with the rural surroundings in a sustainable circular system), 12 “Responsible Consumption and Production” (recycling of nutrients), and 13 “Climate action” (less energy consumption for N fertilizers and carbon accural), and 15 “Life on land” (Restore and promote the use of terrestrial (agro)ecosystems). Further research questions (Box 1) must be answered to minimize risks and maximize the benefits of wastewater irrigation.

Responses