Translation and validation of the COPD Patient Reported Experience Measure (PREM-C9) in Spanish and Catalan

Introduction

Studies of the patient experience in recent years have focused on a new element of value in the quality of healthcare. Patient experience is defined as the sum of all interactions that occur between the patient and the healthcare system within the framework of a specific organizational culture that influences the perception of the person being treated.2 Patient experience can be measured in different ways, including with qualitative studies and surveys.3 Patient Reported Experience Measures (PREMs) are questionnaires developed to assess the patient experience supporting the provision of person-centered and value-based health care.4

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Health Committee launched the Patient-Reported Indicators Surveys PaRIS initiative in January 2017. In that month, OECD Health Ministers met in Paris to discuss the next generation of health reforms. These discussions revealed clear political momentum to pay greater attention to what matters to patients. OECD describes PREMs as psychometrically validated tools to measure patients’ perceptions of their care experience including aspects of care such as continuity of care and care coordination, shared-decision making, provider-patient communication, and waiting times5,6.PREMs differ from patient satisfaction measures7 because they ask patients to provide feedback on their care experience. PREMs also differ from Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in that they aim to provide feedback on the care experience rather than focusing on patients’ views of their health status or health-related quality of life.

Increasingly, PREMS are becoming internationally recognized tools to measure the quality of health services from the patient’s perspective.8 As with any such measurement instrument, PREMs need to be developed following rigorous procedures, and carefully tested and validated. Although some generic PREMs exist,9 i.e. instruments that can be applied across a range of patient populations, there are also an increasing number of PREMs, which are aimed at specific patient populations. Such tools can focus on the particular needs and interests of specific groups of patients or patients undergoing a specific clinical process or intervention.

Accurately and reliably capturing the patient experience, in terms of both the impact of the illness itself and its treatment, is central to understanding how to optimize patient quality of life and the healthcare they receive. To do that, appropriate tools are necessary, including self-report questionnaires, which have been demonstrated to be reliable, valid, and sensitive to change. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), although measures of health-related quality of life have been available for some time,10 there are relatively few tools available to capture the patient experience of healthcare. One such tool is the COPD patient-reported experience measure 9-item list (PREM-C9), which was developed in the UK and which initial studies showed to be reliable and valid. Given that no such tool is available to assess the experience of COPD patients managed within the Catalan Health Service, it was interesting to translate and validate the instrument for use in that context.11 As far as we are aware, this is the first time the PREM-C9 has been validated in a language other than English. Its translation into Spanish will significantly broaden the scope for its use, as Spanish is the official language of 20 countries.

The PREM-C9, which is intended for use in patients with COPD12,13 was developed following a rigorous process involving substantial consultation with patients and caregivers and initial psychometric testing showed that it has satisfactory measurement properties. Having such a tool available can potentially contribute to the evaluation of the impact of the disease and assessment of the care received. However, as the concepts relevant to patients and the organization of health care can vary between countries, it is important to ensure a rigorous process of cross-cultural adaptation is followed when planning to use a questionnaire like the PREM-C9 in another country and language.

Before wider use, it is also important to ensure that new language versions show good measurement properties in the target population. Although the original authors did a thorough job of item reduction and exploring scale structure using the Item response theory approach, and of exploring convergent validity with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale (HADS), other aspects of construct validity, such as known groups’ validity and further investigation of structural validity via the analysis of factor structure, have not been performed to date. There is a clear grouping of items within the PREM-C9 into three subcategories, but no work was done with the original version to determine the extent to which those items form distinct clusters, which would allow for sub-scale scoring. If it is possible to score the instrument in this way, it could facilitate the interpretation of scores when using the PREM-C9.

Objectives

The aim of the current study was to test the validity and reliability of the PREM-C9 in Catalan and Spanish. We took the opportunity to expand on the psychometric testing of the original UK English version by exploring the instrument’s factorial structure and investigating its capacity to discriminate between relevant groups of patients (known groups’ validity). A further aim was to explore the impact of different demographic and clinical characteristics on overall PREM-C9 scores using multiple regression model.

Based on the results of the analyses performed, we provide suggestions as to how the questionnaire could be used and give indications about the interpretability of results with one global summary score analysis for two or three sub-scales or with individual item analysis.

Methods

Study design and participants

This observational study was conducted on two samples of COPD patients recruited in the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona and Hospital Mútua Terrassa based on the following criteria: age≥18 years; a confirmed diagnosis of COPD and able to consent and sign a consent form, able to follow written and verbal instructions in Catalan and Spanish. Only patients with a clinical diagnosis of COPD based on the patient’s medical history and the presence of airflow obstruction confirmed by spirometry were eligible for inclusion in the study. Participants who met any of the following criteria were excluded: asthma/pulmonary fibrosis, who are nearing end of life and had significant other co-morbidities such as severe heart failure. The patients who had been discharged from the hospital in the last 15 days were excluded. The study period was between March and June 2022.

The questionnaire was self-completed. The questionnaire was administered in paper and electronic form. The electronic survey was created using Lime Survey software.

Sample size

The sample size was based upon a criterion of ten participants per number of items in the questionnaire (i.e. 10 × 9 = 90)14 which was considered sufficient for the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and multiple regression analysis.15

Study variables

Data was collected on the following variables in the order they are detailed below. All questionnaires were self-completed in paper or digital format. Participants were given the option of responding in Catalan or Spanish.

Sociodemographic data

Sociodemographic data collected included sex (male/female), age, educational level, and personal support. Educational level, (not completed; primary level; high school; Technical apprenticeship; university). Not completed means that the respondent did not finish obligatory primary education. Technical apprenticeship is a structured training program that combines on-the-job learning with classroom-based instruction. Personal support at home included the following response categories: living alone; living with company; living with one or more family relatives; living with non-family members; living in a nursing home).

Clinical data collected included

years since COPD diagnosis (>10 years; 5–10 years; <1 year); number of chronic diseases (0; 1–2; 3–4; >5); hospital COPD admissions per year (none; 1; ≥2).

The MRC Dyspnoea Scale

Reference16 was used to assess the degree of dyspnoea and the extent to which breathlessness affects mobility. The MRC Dyspnea Scale includes the following categories: breathlessness with strenuous exercise; breathlessness while; walking fast on level ground; walking slower than other people because of breathlessness; stopping for breath after a few minutes on level ground; being too breathless to leave the house).

Accessibility to healthcare services

accessibility to healthcare was assessed through five questions regarding various aspects of accessibility to healthcare services: access to hospital day services, ease of access to primary healthcare services, ease of in-person access to primary care services, ease of phone access to the pulmonologist, ease of in-person access to the pulmonologist. The response categories for each question were a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (nothing) to 5 (a lot).

The PREM-C9 Questionnaire

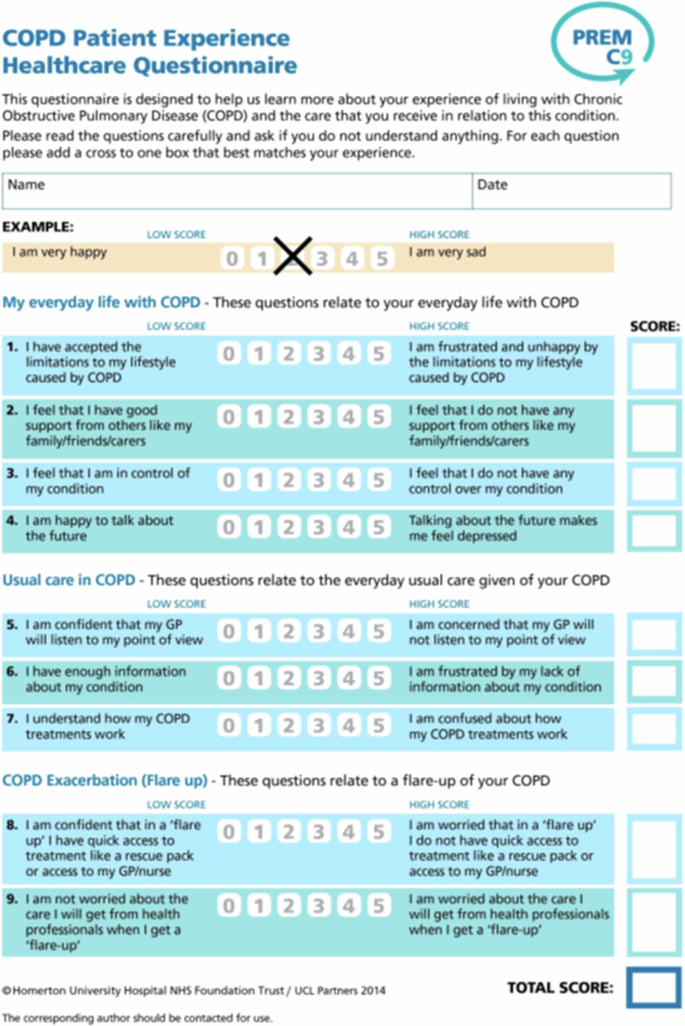

The PREM-C9 is a scale developed and validated within the English healthcare context to better measure and understand the experience of patients with COPD and the care they receive. It consists of 9 items distributed in 3 subscales that measure the impact of COPD in the daily lives of patients, their opinion of the health care they receive, and their expectations about the care they will receive in case of an exacerbation of the disease (Fig. 1). The PREM-C9 instrument describes the patient experience of COPD and items are scored on a six-point Likert scale from 0 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Summing scores from each item leads to a raw total score between 0 and 45. The 9-item version of the questionnaire demonstrated12 good fit to a Rasch model (xp = 0.33; PSI = 0.75) and good distribution of item scores. PREM-C9 scores correlated moderately with other measurement tools such as the COPD Assessment Test and the HADS Scale, and test-retest reliability was considered acceptable.12

The figure contains the items of the COPD Patient Experience Healthcare Questionnaire.

Satisfaction with care

Participants were also asked to rate their overall satisfaction with healthcare services by choosing one of five response categories: very satisfied, quite satisfied, moderately satisfied, slightly dissatisfied, and very dissatisfied.

Cross-cultural adaptation

Before using an instrument such as the PREM-C9 in another cultural or linguistic setting, it is important to ensure a rigorous process of translation and cultural adaptation. In the present study, translation followed the International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcome Research (ISPOR) Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures17. As both Catalan and Spanish are Roman languages, which means they evolved from Latin and both are official languages in Catalonia being widely spoken, the PREM-C9 was translated into both languages. The adaptation process consisted of forward and back translation by pairs of translators working independently and in-depth cognitive-debriefing interviews in COPD patients with a range of demographic and clinical characteristics to assess comprehension and acceptability. The face validity testing was performed by a sample of COPD clinicians and nursing staff. Harmonisation between the Catalan and Spanish versions formed the last stage of the adaptation process. Some aspects of the cross-cultural adaptation have been published previously11.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (HCB/2021/0540) and Hospital Mútua de Terrassa (CPMP/ICH/135/95) and was conducted between June and July 2022. Participants gave fully informed, written consent to participate.

Analysis

Questionnaires with missing values on any of the items of the PREM-C9 questionnaire were excluded from the analysis because complete data were considered a requirement for the known group validity and regression analyses.

For continuous data, descriptive statistics were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed variables. For categorical data, descriptive statistics were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The distribution of answers across response categories was assessed for each item, and potential ceiling and floor effects were estimated by calculating the percentage of subjects with the maximum and minimum possible scores for the PREM-C9, respectively. A ceiling effect was considered to be present when 15% or more of patients obtained the maximum score.18

Structural validity of the PREM-C9

Structural validity can be defined as the degree to which scores of a scale are an adequate indication of the dimensionality of the construct being measured19,20, Although the original authors only proposed one overall score for the PREM-C9, items are clearly grouped within the questionnaire itself into 3 categories (My everyday life with COPD, Usual care for COPD, and COPD exacerbation), suggesting that there may be an underlying dimensional structure to the items. We were interested in exploring whether this was in fact the case, as being able to score the questionnaire using sub-scales could facilitate interpretation. For example, patients could score well on one dimension but less so on another. To test this possible dimensional structure we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used to assess the adequacy of the model. Global model fit was evaluated by the following fit indices: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) – values close to 0.06 or below indicate good fit21,22. Values lower than 0.08 suggest adequate model fit22,23 and values ≥ 0,10 indicate poor model fit22,23. Comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥ 0.95 suggest good model fit22,21 and values from 0.90 to < 0.95 indicate acceptable model fit24.

Known groups’ validity

This type of construct validity assesses an instrument’s ability to distinguish among distinct groups who are expected to show different scores on the construct or measure of interest based on their demographic and/or clinical characteristics. Known group validity was estimated using non-parametric tests. Three hypotheses were identified and tested:

-

1.

Participants with a lower level of education will tend to have poorer scores on the questionnaire.

-

2.

Participants with higher breathlessness scores will have poorer scores on the questionnaire overall, particularly because greater breathlessness will impact on their experience of the illness itself.

-

3.

Participants reporting higher levels of overall satisfaction with care will have better scores on the questionnaire overall.

Given the non-normal distribution of scores on the PREM C9, between group differences to test the above hypotheses were performed using non-parametric tests. Effect size between any pairs of adjacent categories for which statistically significant differences were found on the variables of interest was calculated using Wilcox’s Q.

Multiple regression analysis

A multiple regression model was carried out to determine which sociodemographic and clinical factors contributed most to differences in the PREM-C9 total score. The dependent variable was the overall PREM-C9 score. Independent variables included were: age ((categorized as <60years; 61-70 years; 71–75 years; >75 years to ensure a reasonably even spread of patient numbers in each age group)); Educational level; satisfaction; breathlessness; Hospital admissions per year (years since disease diagnosis and Accessibility to healthcare. Categories included for each variable within the model were as described in the section on study variables above, except for age which was categorised as <60 years, 61–70 years, 71–75 years, and>75 years to ensure a reasonably even spread of patient numbers in each age group, and accessibility which was transformed from a categorical to a continuous variable by calculating the average score of the five aspects measured. Similar models were constructed to test for association of the independent variables with PREM-C9 sub-scale scores.

In all statistical analyses, significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.

Reliability analysis

Reliability (i.e. the extent to which the items comprising the scale measure the same construct) was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, with a coefficient of 0.70–0.90 considered to indicate satisfactory reliability. Reliability was assessed for the Spanish and Catalan versions separately.

Results

Cross-cultural adaptation

Two translators who were native speakers of the target languages independently prepared a translated version of the questionnaire, two independent versions in Catalan and two independent versions in Spanish. In the back translation phase, two native English speakers translated each the Catalan and Spanish versions back into English. Therefore, four native English speakers participated in this process. The back-translations for each version were reviewed and compared, both with each other and with the original version. In the cognitive debriefing phase, the questionnaire was tested in a convenience sample of 10 patients with COPD (5 in Catalan and 5 in Spanish). There were 9 men and 1 woman and the average age was 68.8 years. In the face validity and harmonization phase, 7 healthcare and nurse staff participated in the study. They were asked about the relevance of content overall, whether they considered any important aspect to be missing, bearing in mind the objective of the questionnaire, and whether the patients they see on a daily basis would have trouble answering the questionnaire. In addition to these general questions, professionals were also asked for their views on specific aspects of the questionnaire, such as the most appropriate way to refer to an exacerbation of COPD so that patients could better understand it.

Overall, the language used in the original version of the questionnaire did not cause substantial problems for translation into Catalan and Spanish. There was substantial discussion around some of the terms used in the original version, however. For example, ‘frustrated’ can be a difficult word to translate as, while a direct translation exists in Catalan and Spanish, it is not widely used, especially among the older population. After discussion, therefore, ‘frustrated’ was replaced by ‘disappointed’ or ‘worried’ in the translated versions (depending on the item), based on a proposal by patients, as that seemed to be the closest natural-sounding alternative. Importantly, we also found substantial resistance to the way the numbers were ordered in the response scale. In the original version, the response scale runs from 0 (representing the most positive experience) to 5 (representing the most negative experience). However, patients in Catalonia are much more used to seeing higher numbers representing a more positive experience and were sometimes confused about how to answer. For that reason, a decision was made to reverse the numbering in the Catalan and Spanish versions, which means that whereas a higher score represents a ‘worse’ outcome on the original version, a higher score on the Catalan and Spanish versions represents a ‘better’ outcome.

Sample characteristics and data quality

Analysis of the missing responses for the PREM-C9 did not show any clear patterns in the missing data, which appear to be at random. A total of 239 individuals (male 68.9%; female 30.2%). were therefore finally included in the analysis, of which 61.4% completed the Catalan version and 38.7% the Spanish version. Overall, 50.6% of the total sample were over 71 years old. On the breathlessness scale, 28.8% of participants reported getting breathless with strenuous exercise, 30.2% when hurrying on level ground, and 16.7% reported walking slower than other people because of breathlessness. Table 1.

Acceptability and data quality

Ceiling and floor effects were within acceptable limits in this study, with 2 patients (0.8% of participants) scoring 0 (the floor effect) and 18 patients (7.5%) with the maximum score of 45 (ceiling effect).

Internal consistency

The measure’s internal consistency, was high for both the Spanish [Cronbach’s alpha=0.802 and Catalan [Cronbach’s alpha=0.875] versions.

Structural validity

Confirmatory factor analysis

The results of the CFA showed that the majority of items load on to their intended dimensions except for item 2 of the subscale “My everyday life with COPD”, which had the lowest factor loadings for both language versions (0.48 and 0.54 for the Spanish and Catalan versions, respectively). For the Spanish version, item 5 did not load as strongly as might be expected, The goodness-of-fit indices were very close to acceptable values for the CFI/TLI of 0.90. Factor loadings and factor correlations for the CFA model are presented in Table 2.

Known groups’ validity

As shown in Table 3, two of the three hypotheses tested to assess known groups’ validity were confirmed, with statistically significant differences found between response categories on the satisfaction (p < 0.001) and breathlessness (p = 0.023) scales. No statistically significant differences were observed between the different categories for the education variable. Bivariate analysis showed that there were statistically significant differences at p < 0.05 when comparing “Somewhat satisfied” (median [IQR] score of 26 [21–31]) vs “Quite satisfied” (36 [29.3–40]) and “Quite satisfied” vs “Very satisfied” (40 [33–43]) on the satisfaction scale, and between “Being too breathless to leave the house” (27 [20–36]) and “Stopping for breath” [3730–40] on the breathlessness scale. Effect sizes for those between-group differences were 0.429, 0.227, and 0.296, respectively, indicating small to moderate differences in score.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with PREM-C9 scores

The results shown in Table 4 confirm that low levels of satisfaction and greater breathlessness were associated with significant reductions in PREMS C9 scores. For example, a rating of ‘Somewhat satisfied’ on the satisfaction scale is associated (p < 0.01) with a mean (2.5%–97.5% CI) increase (poorer overall COPD experience) of 7.18 (10.95–3.41) points on the PREMS C9 compared to the reference category of ‘Very satisfied’. Likewise, a rating of “Somewhat or very dissatisfied” is associated with an increase of 8.62 (14.33–2.91) points on the PREMS C9. On the breathlessness scale, three categories showed a statistically significant association with higher (poorer experience) scores on the PREMS C9 when compared with the reference category of “Breathless with strenuous exercise”. “Hurrying on level ground”, “Stopping for breath” and “Too breathless to leave house” were associated with mean/median (2.5–97.5% CI) PREMS C9 score increases of 4.48 (8.01-0.95, p = 0.01), 5.95 (9.92-1.98, p < 0.01), and 9.58 (15.61-3.55, p < 0.01), respectively. In addition, we found that a time from diagnosis of 1 year or less was associated with poorer COPD experience with a mean/median (2.5–97.5% CI) increase in PREMS C9 score of 6.40 (11.65 – 1.15, p = 0.02) compared to the reference category. Finally, accessibility also showed a statistically significant association with PREMS C9 score. On the other hand, age, number of chronic diseases, educational level, and number of hospital admissions were not found to be associated with PREMS C9 scores.

Discussion

This is the first study we are aware of to explore the psychometric properties of translated versions of the PREM-C9, a new measure of patient experience for those with COPD. It is important to re-assess the psychometric properties of translated versions of PREM, or PREM measures, to ensure that translation has not affected their measurement properties. In addition, in this study we went a step further by further exploring the dimensional structure of the questionnaire and by evaluating its known groups’ validity, as well as re-assessing its reliability. The overall results indicate that the questionnaire adheres to a three-factor model, and has acceptable known groups validity and reliability.

The Spanish and Catalan versions of the PREM-C9 showed high Cronbach’s alphas with respect to the reliability of the translated versions indicating a very satisfactory level of internal consistency. The results indicate that, in the translated versions, the items cluster around the same concept and that the instrument provides a highly reliable estimate of a patient’s COPD experience.

As part of the current study, we also explored the instrument’s structural validity via the use of factor analysis. Although in the original study the authors demonstrated unidimensionality of the overall construct (which they labeled ‘patient experience’) using Rasch analysis, they also refer to three dimensions of experience within that overall construct, i.e. “My Everyday Life with COPD”, “Usual care in COPD”, and “COPD Exacerbations”. It was not clear in the original study, however, whether there was any psychometric support for this proposed scale structure. The results of the factor analysis performed here suggest that, in general, there is support for such a structure, although item 2 of “My Everyday Life with COPD” (in the Catalan version) and items 2 and 5 of “Usual care in COPD” (in the Spanish version) do not load as strongly as might be expected on to their proposed sub-scales. The lower factor correlation observed in item 5 in the Spanish version might be attributed to the fact that the respondents to the Spanish version were, on average, older and had a lower level of education compared to those who participated in the Catalan version and may not have fully understood either the wording or the intention of the item. For example, they might not appreciate why clinicians should listen to their point of view and be happier with a more paternalistic relationship.

Based on these results, we recommend using the overall scale score as the primary outcome when applying the PREM-C9. While the availability of sub-scale scores can be useful when presenting and interpreting results with the questionnaire (for example, we might be more interested in experience of the illness itself, i.e. items 1 – 4, rather than confidence in health care providers in case of an exacerbation, and it is therefore useful to be able to separate out those items), further investigation with the Spanish version, and with the original English version, is required before the use of sub-scale scores can be recommended. It is also possible that individual PREM-C9 items could be useful in identifying patients with, for example, poor levels of support (item 2) or who feel they do not have enough information about their condition (item 6) and actions could then be taken to address such issues. Though such use of the instrument has not been explored to date, future research could explore this type of application.

With regard to the testing of known groups’ validity, two out of our three hypotheses were fulfilled, for satisfaction and breathlessness, but not for educational level. Despite the negative finding for the latter, we think these results provide preliminary evidence for known groups’ validity, given that satisfaction and breathlessness were probably the strongest candidates to be associated with overall COPD experience. Education was included because we believed that those with lower levels of education might have lower scores on items such as being happy with the amount of information they have about their condition and its treatment or their understanding of how treatment works. The fact that that did not appear to be the case is interesting and may warrant further investigation. Furthermore, the finding that PREM-C9 scores did not vary by educational level might be of interest to other researchers wishing to investigate the known groups’ validity of the PREM-C9, or other PREMs measures. The results, therefore, contribute to the evidence base around which factors affect PREM scores, an evidence base that is still relatively scant, given that psychometric analysis of PREMs is at a relatively early stage compared to PROMs.

The finding that educational level was not associated with PREM-C9 scores was supported by the results of the multiple regression analysis, which also showed that overall lower levels of overall satisfaction with health services and a greater degree of breathlessness were associated with poorer scores on the PREM-C9, thereby supporting the results of the known groups’ analysis. The regression analysis also showed that those with a more recent COPD diagnosis also had poorer scores on the PREM-C9, which might be due to those patients having to adapt to their new situation, though it should be noted that the number of patients in that category was quite low.

Our study had several strengths. Concerning the translation, or cultural adaptation, of the instrument from English into Catalan and Spanish closely followed internationally recognized recommendations and included forward and back translation, cognitive debriefing interviews with COPD patients, and an initial face validity check with clinicians and nurses attending COPD patients. This type of rigorous translation procedure is important to avoid pitfalls such as the incorporation of inappropriate language or concepts in the translated version25. For example, without such a rigorous procedure, we may have missed the inappropriateness of the original response scale ordering for use in Catalan- and Spanish-speaking patients. On the other hand, the rather general, culture-free content of the questionnaire and the use of plain, non-colloquial language in the original version facilitated its development in Catalan and Spanish.

Another strength of the current study was the large sample size, which was substantially greater than that in the original study. This also allowed us to develop a regression model that permitted exploration of the demographic and clinical variables associated with PREM-C9 scores.

Study limitations include the fact that we did not assess test-retest reliability or responsiveness, due to practical difficulties involved in recruiting patients for longitudinal observation. The original English version showed acceptable test-retest reliability and some evidence of responsiveness in patients receiving pulmonary rehabilitation and investigation of these two elements should be the target of future research with the Catalan and Spanish versions. Another limitation arises from the sample size in the analysis of known group validity, which may not be sufficient to demonstrate more conclusive results. We recognize that future studies can contribute to confirming or strengthening these findings. However, the overall results and tendencies observed provide reasonable support for instrument’s construct validity. An additional potential limitation to our study was the need to pool results from the Catalan and Spanish versions for known groups’ and regression analysis. Although we had originally intended to have similar sample sizes for the two languages, which would have allowed for separate analysis, in the event it was not possible, in part because of the higher levels of patients who did not respond to any item of the PREMC9 questionnaire of the Spanish version. On the other hand, given that the two languages have many features in common and reflect a reality where both languages are spoken, this approach was considered reasonable under the circumstances, and has been adopted in previous studies of this type26,27.

In conclusion, the Catalan and Spanish versions of the PREM-C9 have shown good reliability and known groups’ validity. Though further research is required, the evidence generated to date with these versions and with the original English version, suggests that the instrument is appropriate for use as a measure of overall COPD experience. Based on the results found here, we would not currently recommend using sub-scale scores with the PREM-C9 and would recommend that users report results using the overall score. Future studies with the instrument should further assess its underlying factor structure and the possibility of using it as a screening tool to identify individual patients and/or sub-groups of patients with negative elements of patient experience for which solutions might be available. Future research with the Catalan and Spanish versions should focus on investigating responsiveness.

Responses