Translocation-specific polymerase chain reaction in preimplantation genetic testing for recurrent translocation carrier

Introduction

Constitutional translocations are among the most frequent structural chromosomal abnormalities in humans. Although balanced carriers of these translocations usually manifest no clinical symptoms, they can often have reproductive issues, such as male infertility, recurrent spontaneous abortions, and offspring with a chromosomal imbalance that can lead to multiple congenital anomalies with associated intellectual disabilities. These problems are all the result of the recurrent generation of embryos with copy number abnormalities via an unbalanced segregation of translocated chromosomes. Euploid embryo selection using a combination of in vitro fertilization (IVF) and preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) using biopsied samples from trophoectoderm (TE) cells have been used to overcome these issues.

It is generally unnecessary in preimplantation genetic testing for structural rearrangements (PGT-SR) to distinguish balanced reciprocal translocation from normal diploidy. This is because a determination of euploidy or aneuploidy at the translocation segment through the simple detection of copy number variation (CNV) changes is sufficient for embryo selection that will avoid possible reproduction problems due to unbalanced translocation [1]. However, distinction between balanced reciprocal translocation and normal diploidy is occasionally required for some euploid embryos since balanced carriers can sometimes have reproductive problems or manifest pathogenic phenotypes. It is technically challenging to distinguish balanced reciprocal translocation from normal diploids using quantitative analysis such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) or microarray-based PGT. In the early days, detection using microarray of translocation-associated microdeletion at the breakpoint was used as a hallmark of an embryo carrying a translocation [2]. The haplotype of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) determined by trio-analysis using parental samples has also been successfully used to distinguish a translocated chromosome from its normal counterpart during embryo selection [3]. Determination of a translocation breakpoint at a nucleotide level of resolution using the mate-pair method has enabled translocation-specific PCR to be used to detect the translocation directly in biopsied samples from an embryo [4]. Further to this, recent advances in long-read sequencing technology have facilitated the identification of translocation breakpoints and simultaneously the further acquisition of haplotype information for nearby SNPs [5, 6]. However, determinations of these breakpoints must be custom-made for each patient, and long-read sequencing requires substantial time and effort and is costly.

t(11;22)(q23;q11.2) and t(8;22)(q24.13;q11.21) are the two well-known recurrent constitutional translocations in humans. The breakpoints are different at the nucleotide level among each translocation carrier, but are located within a common region of a few hundred base pairs that constitute characteristic palindromic AT-rich repeats (PATRRs) on each chromosome [7, 8]. Since the size of these PATRRs is less than 1 kb, it was possible to establish a specific PCR method for detecting all PATRR-related t(11;22) or t(8;22) translocations. For the detection of CNV alterations in PGT-SR, genomic DNA amplified from TE biopsy samples via whole genome amplification (WGA) is used. Multiple annealing and looping-based amplification cycles (MALBAC) or its derivative looping-based amplification (LBA) is generally used as the WGA method since the quantity of LBA-amplified WGA include less amplification bias than the other approaches such as multiple displacement amplification (MDA) [9, 10]. Notably however, it is empirically known that the relatively lower genome coverage of LBA may hinder the establishment of region-specific PCR [11]. In this present study, we compared these two WGA methods to distinguish between normal diploid and balanced reciprocal translocations in a PGT-SR for two palindrome-mediated recurrent reciprocal translocations; t(11;22) and t(8;22).

Materials and methods

Samples

All samples were obtained at the authors’ institution, Asada Ladies Clinic and Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital. Balanced reciprocal translocation carriers for t(8;22)(q24.13;q11.2) or t(11;22)(q23;q11.2) were enrolled and gave written informed consent for the experimental use of discarded embryos for which PGT-SR data were available. Discarded embryos that were unsuitable for transfer due to unbalanced translocations or translocation-unrelated aneuploidy were subsequently collected. The use of discarded embryos has been approved by the Ethical Review Board of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) (Approval number 107). This study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board of Fujita Health University (Approval number HG24-017) and registered to the UMIN-CTR (University Hospital Medical Information Network – Clinical Trials Registry) (Registration number UMIN000057033).

WGA

Initial diagnostic PGT-SR was performed using WGA-amplified DNA obtained via TE biopsy. The LBA-derivative method was applied to diagnostic PGT-SR owing to relatively unbiased amplification. For the discarded embryos resulting from PGT-SR findings, we performed additional biopsies and conducted WGA using the multiple displacement amplification (MDA) method. For the WGA by LBA method, we used Ion SingleSeq Reagents in the ReproSeq™ PGS kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA) or SurePlex in the VeriSeq PGS assay system (Illumina, San Diego, CA), and REPLI-g™ Single Cell Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used for WGA by MDA. All procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and extracted DNA were quantified by Invitrogen™ Qubit™ dsDNA Quantification Assay Kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Eugene, OR, USA).

Chromosome copy number analysis

We used the ReproSeq™ PGS kit for chromosomal copy number analysis. Library preparation for NGS analysis was conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Shallow whole-genome sequencing for robust copy number profiling was carried out using the Ion Chef equipment and the Ion S5 sequencer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Copy numbers were evaluated using IonReporter system. We also used the VeriSeq PGS assay system (Illumina, San Diego, CA) for chromosomal copy number analysis. Nextera libraries were prepared from the WGA-amplified DNA and subsequently sequenced with a VeriSeq PGS assay system by MiSeq (Illumina). The sequencing data were analyzed using BlueFuse Multi analysis software v4.5. Karyotype reports were produced manually.

Translocation-specific PCR

PCR primers were designed just outside the palindromic region where the breakpoints of the recurrent t(11;22) or t(8;22) translocations reside (Fig. 1). For t(8;22), the ~850 bp products from the der(8) breakpoint junction fragment were amplified with PATRR8-512 F (5′-GATTACATATGGCATCTGGTAGGCTG-3′) and PATRR22+178R (5’-CATGATTCTGGATAACTTCCAAA-3’) primers, while the~650 bp products from the der(22) breakpoint junction fragment were amplified with PATRR8+227R (5′-GTGCCAAAATGTCAAGTCATCTGTG-3′) and PATRR22-394 F (5’-TCAGTTTATTCCCAAACTCCCAAAT-3’) primers. We applied a two-step PCR system to amplification of the AT-rich translocation breakpoint junction fragment. The cycling conditions for the two-step PCR system were as follows: 94 °C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles at 98 °C for 30 s and 60 °C for 5 min. The resulting PCR products were electrophoresed at 135 V for 15 min on 2% agarose gels in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer using the Mupid-exU electrophoresis system (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan). The gel was stained with 0.5 µg/mL of ethidium bromide, and the PCR products were detected using the FAS-III ultraviolet transilluminator (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). For t(11;22), the der(11) products were amplified with JF11 (5′-GGAAGTTAGAGAAAACTGAGAA-3′) and JF22 (5′-CCTCCAACGGATCCATACT-3′), while the der(22) products were amplified with JF11.2 (5′-AACACTCCCACTGACAGCTA-3′) and JF22 primers. The PCR conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 1 min and a final incubation at 60 °C for 5 min. PCR reactions were performed using LA Taq DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) and the resulting amplified products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels. Blood or cheek swab samples from our t(8;22)(q24.13;q11.2) or t(11;22)(q23;q11.2) carriers were positive for these translocation-specific PCR tests. The size of the PCR products was approximately 1.2 kb for der(8) and 1.0 kb for der(22) at t(8;22), and approximately 900 bp for der(11) and 850 bp for der(22) at t(11;22).

Schema for translocation-specific PCR. Schematic diagrams of the t(8;22)(q24.13;q11.2) are shown on the left, and the t(11;22)(q23;q11.2) is shown on the right. Facing arrows within the chromosomes indicate the palindromic regions. Translocation-specific PCR was performed with primers designed in the flanking regions of the palindrome in each chromosome (green, blue, cyan, and purple arrows, respectively). The illustration of chromosomes is from TogoTV (©2016 DBCLS TogoTV/CC-BY-4.0)

Results

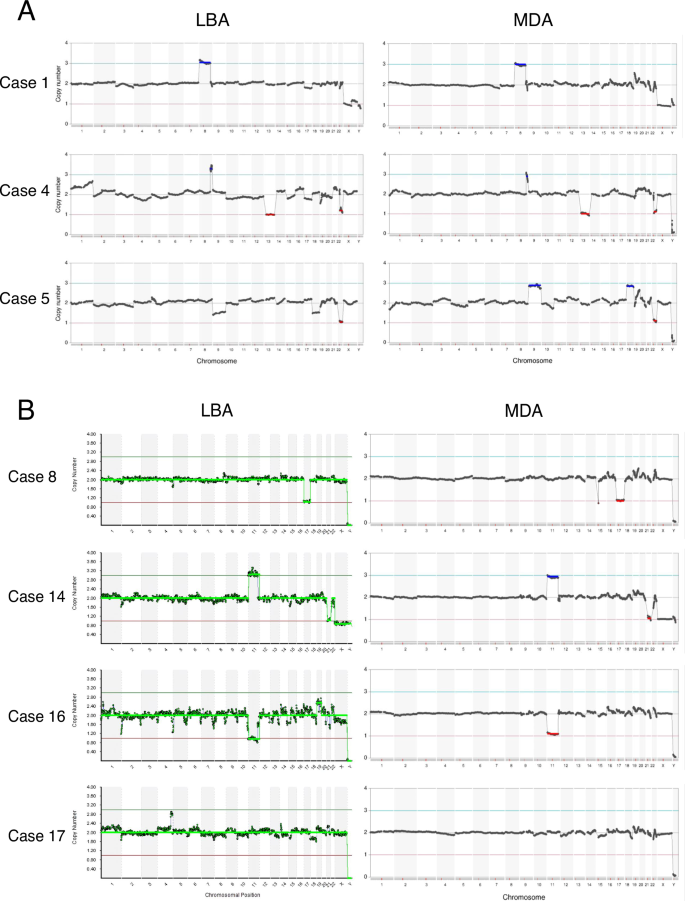

Fourteen specimens from t(11;22)(q23;q11.2) carrier embryos and five from t(8;22)(q24.13;q11.2) were collected. Each specimen was biopsied at two locations in the embryo, and WGA was performed using the LBA and MDA methods, respectively. We first performed CNV analysis and compared the quantitative performance of the MDA and LBA methods (Fig. 2A, B). The chromosomal contents estimated by NGS were almost equivalent and generally consistent regardless of the WGA method used. The partial or whole aneuploidy analysis of translocation-related chromosomes, as well as of translocation-unrelated chromosome, showed similar results. In some embryos, inconsistent findings were observed. For example, Sample 1 was determined to have an 8pter-q24 trisomy by CNV analysis, suggesting that it should carry der(8)t(8;22) instead of normal chromosome 22. However, 22pter-22q11 monosomy was not detected in this specimen possibly due to the small size of the region and its highly repetitive nature with region-specific segmental duplication (Fig. 2A) [12]. Similarly, we could not detect CNV for 22pter-22q11 in some embryos from the t(11;22) carrier (Fig. 2B, Samples 14 and 16). Other inconsistencies were considered to be noise or a sampling bias caused by somatic mosaicism. These data are summarized in Table 1.

Results from CNV analyses of TE biopsy samples in PGT-SR for t(8;22)(q24.13;q11.2) (A) or t(11;22)(q23;q11.2) carriers (B). In each figure, WGA by LBA is shown at the left and by MDA on the right. The CNV profiles were almost equivalent for each WGA sample. In Sample 17, partial trisomy 4 was only observed with LBA, which was considered to result from a mosaicism sampling bias, and Sample 5 was considered to include chromosomal nondisjunction pairs. Each embryo was biopsied at two locations in the TE, but they were not collected from the exact same site. Sampling bias may potentially arise due to somatic mosaicism depending on the specific location of the TE biopsy. However, the results of the CNV analysis of translocation chromosomes would not be affected by difference of biopsy sites since it is derived from germline transmission

We next performed translocation-specific PCR on the WGA products to detect each derivative chromosome. The results indicated that the WGA products amplified using the MDA method were able to yield each derivative chromosome. For example, Sample 4 was determined to be 8q24-qter trisomy with 22q11-qter monosomy by CNV analysis, suggesting that it harbors der(22)t(8;22) instead of normal chromosome 22 (Fig. 2, Table 1). Translocation-specific PCR testing of Sample 4 was negative for der(8) and positive for der(22), which is consistent with the CNV analysis (Fig. 3A, #4). In another example, Sample 1 was determined to be carrying der(8)t(8;22) instead of normal chromosome 8 as mentioned above (Fig. 2, Table 1). Consistently, translocation-specific PCR analysis of this sample was positive for der(8) and negative for der(22) (Fig. 3A, #1). On the other hand, none of the translocation derivative chromosomes were detected by PCR when using the LBA-amplified DNA (Fig. 3). All the PCR results obtained for the t(11;22) and t(8;22) embryos are summarized in Table 1.

Results of translocation-specific PCR for t(8;22)(q24.13;q11.2) and t(11;22)(q23;q11.2). A Results of translocation-specific PCR for der(8)t(8;22) and der(22)t(8;22). B Results of translocation-specific PCR for der(11)t(11;22) and der(22)t(11;22). Sample numbers are presented on the top line, while the corresponding WGA methods are listed on the bottom line. L indicates looping-based amplification (LBA), M multiple displacement amplification (MDA), P positive control, N negative control. Each balanced translocation carrier unrelated to the family was used as a positive control (lanes P); non-carrier was used as a negative control (lanes N). The first lane on the left contains size markers and the arrows indicate the 1 kb markers

Finally, we attempted to distinguish normal euploidy from a balanced translocation using this same methodology. Sample 8 was an embryo from a t(11;22) carrier in which the copy number of chromosomes 11 and 22 were found to be normal by CNV analysis but this specimen harbored a translocation-unrelated monosomy 17 (Fig. 2B, Table 1). Since we could not determine whether this sample was normal without t(11;22) or a balanced t(11;22) translocation, we performed translocation-specific PCR. The results showed positivity for both the der(11) and der(22) PCR, indicating that the embryo carried a balanced reciprocal translocation (Fig. 3B, #8, Table 1). Similarly, Samples 3, 9 and 17, all determined to be normal or to harbor a balanced translocation by CNV analysis, were proven to be normal as the PCR results for derivative chromosomes were negative in each case (Fig. 3, Table 1). Interestingly, two t(11;22) samples (Samples 11 and 18) that appeared to be monosomy 22 in the CNV analysis showed PCR positivity for both der(11) and der(22) (Similar results as Fig. 3B, #8), suggesting that they were representative examples of an interchange monosomy via 3:1 segregation.

Discussion

We have here compared MDA and LBA as WGA methods for PGT-SR, with a particular focus on distinguishing between normal diploids and balanced reciprocal translocations. In CNV analysis, both of the MDA and LBA methods yielded consistent results, suggesting that these were stable approaches for conducting PGT-SR. Historically, the MDA method using φ29 DNA polymerase with random primers under isothermal conditions has been widely applied in WGA, but it has shown problems with its quantitative performance and is not generally used for CNV analysis. To overcome the limitations of the MDA, MALBAC or LBA were developed as an alternative WGA method for use in CNV analysis. In that system, synthesized DNA preferentially amplified in earlier cycles forms a loop structure that can avoid excess amplification in later cycles [9]. It is not unreasonable to expect therefore that LBA would perform better in quantitative analysis. However, our present results have indicated no problems in interpreting the results when MDA is used in CNV analysis, suggesting that advances in MDA amplification technology, such as fine tuning of reaction buffers or protocols, produced a performance for this technique that was comparable to LBA.

Both the MDA and LBA-amplified WGA products failed to detect copy number abnormalities at the proximal 22q11 region generated by unbalanced t(11;22) and t(8;22) translocations. The predicted size of the unbalanced region estimated by the breakpoint location is ~5 Mb, which may be above the threshold for detection by NGS-based CNV analysis [13]. However, this region includes many segmental duplications and low copy repeats that might hinder the quantitative analysis of the sequence reads [12]. This might potentially require careful attention in clinical practice since it could potentially lead to a misdiagnosis from PGT-SR. However, unbalanced translocations usually involve copy number abnormalities of two translocation-related chromosomes. Even when CNVs are hard to detect at the proximal 22q11 region, the size of the unbalanced region of the partner chromosome, 8q24.13-qter or 11q23-qter, is large enough to be detected by standard CNV analysis. Thus, it does not affect the sensitivity of the detection of unbalanced translocations in PGT-SR for t(11;22) and t(8;22).

It was notable that the MDA-amplified WGA DNA samples yielded a substantial amount of translocation-specific PCR products. The positive PCR findings in this regard correctly reflected the presence of each translocation derivative chromosome predicted by CNV analysis. In contrast, the LBA-amplified WGA DNA did not yield any translocation-specific PCR products. Although the LBA method is useful for detecting aneuploidy in PGT-A, and also partial aneuploidy in PGT-SR, it is generally considered unsuitable for use in PGT-M due to coverage bias and amplification product length issues [14]. The WGA product lengths from the LBA method are reported to be shorter than those obtained with the MDA method: 0.2–2.0 kb for LBA and ~10 kb for MDA [15]. Hence, the conventional MDA method is preferentially used for PGT-M since various type of pathogenic variants must be handled. LBA method has been optimized for quantitative analysis. To achieve a cost-effectiveness as a clinical use in PGT, low depth sequencing, usually ×0.01–0.1, is enough for CNV analysis of 1 Mb resolution in standard PGT-SR. However, insufficient genome coverage hinders analysis of each specific locus [11]. Further, translocation breakpoint region might be recalcitrant to amplification due to DNA secondary structure. Reduction of the sequencing cost and increase the read coverage might overcome this weakness of the LBA method. In this sense, it is not surprising that LBA WGA products did not work in the translocation-specific PCR and that MDA appears to be superior to LBA when CNV analysis and translocation-specific PCR are required for the same sample.

Our present methodology allowed us to distinguish balanced translocation from normal diploidy among four samples with putative normal findings by CNV analysis. One sample was finally determined to have a balanced translocation since both the der(11) and der(22) results were positive, and the others were determined as normal diploid since none of the PCR tests for derivative chromosomes were positive. Our data thus suggest that CNV analysis using WGA products amplified with the MDA method, combined with translocation-specific PCR, can successfully distinguish balanced translocation from normal diploidy. In addition, samples appearing to be aneuploid for translocation-related chromosomes in the CNV analysis occasionally showed positivity in both PCR tests for translocation-derivative chromosomes, suggesting that we could use these techniques also to distinguish 3:1 segregations and meiotic errors. Although resolution of the unbalanced translocation as well as accurate quantification of additional germline or somatic aneuploidy needs to be re-evaluated, MDA and translocation-specific PCR, which can distinguish balanced translocation from normal diploidy, has the potential to become standard practice in PGT-SR.

We tested the performance of WGA methods for translocation-specific PCR using recurrent constitutional t(11;22) and t(8;22) embryo samples. The rationale for this approach was that we did not need to set up translocation-specific PCR since these translocations share the same breakpoints located at the center of PATRRs among unrelated families. The breakpoints of the t(11;22) and t(8;22) were located within a few hundred base pair regions, allowing us to use same PCR system with the same primer to detect the translocation junctions. However, since the breakpoints of general reciprocal translocations distribute randomly, it is necessary to determine the translocation breakpoints individually when establishing a tailor-made translocation-specific PCR system. This necessarily requires time, money, and technical effort, and there are still challenges in generalizing the resulting data. Recent advances in long-read sequencing have enabled the detection of breakpoints for structural rearrangements and have spurred the establishment of junction-specific PCR for PGT [16, 17].

Finally, we found using these aforementioned techniques that it became possible to distinguish embryos with various balanced reciprocal translocations from those with normal diploidy using PGT-SR with translocation-specific PCR. Currently in Japan, PGT-SR is used for translocation carriers presenting with reproductive issues due to embryos with unbalanced translocations and thereby selection against embryos with unbalanced translocations or aneuploidy improve the pregnancy rate and reduce the miscarriage rate [18]. Techniques that can be used to detect balanced reciprocal translocations in euploid embryos are essentially prohibited by current Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) regulations unless a severe clinical phenotype is predicted in relation to the balanced translocation carrier [19]. In Japan at present, the potential for future reproductive problems associated with a balanced translocation are not considered sufficient to exclude an embryo from transfer. However, in couples involving a translocation carrier, the psychological burden of potentially passing on reproductive problems to their offspring can be heavy. Balanced translocation carriers face complex psychological burdens characterized by mixed emotions and significant social challenges [20]. Many carriers grapple with the implications for their relationships, particularly with their partners, fearing potential blame, misunderstanding, or rejection. Additionally, carriers experience anxiety about their children’s futures, including concerns about whether to disclose their carrier status to siblings and how to navigate uncertainties surrounding future pregnancies. Therefore, we propose that considering this distinction using the present method is potentially a solution to alleviate psychological burdens when multiple euploid embryos are available for transfer. However, the current Japanese guidelines for PGT-SR address the presence or absence of balanced translocations should not be disclosed, which poses challenges for the clinical application of our methodology in Japan [19]. There might be a concern that the reduction of number of embryos available for transfer affects pregnancy or live birth rates if the balanced translocation embryos are deselected or deprioritized. However, when multiple transferable euploid embryos are available in PGT-SR, our own common experience is that they would like to transfer a normal euploid embryo without any translocations. Our current results demonstrate the technical feasibility of doing just that using a standard PGT-SR system, although we acknowledge that there remain some ethical issues relating to the clinical application of our methodology in Japan. Further discussions on the medical, ethical, legal, and social implications are warranted to establish appropriate indications for PGT-SR in embryo transfer.

In conclusion, we demonstrate a method for distinguishing between normal diploid embryos and those harboring balanced reciprocal translocations that combines an MDA method and translocation-specific PCR. Although some challenges remain in this regard, distinguishing normal diploidy from balanced reciprocal translocations may well become standard practice the future PGT-SR testing.

Responses