Treatment modalities for patients with Persistent Spinal Pain Syndrome Type II: A systematic review and network meta-analysis

Introduction

The pooled prevalence of patients experiencing chronic pain after spinal surgery is 14.9% (95% CI from 12.38 to 17.76)1. According to the International Association for the Study of Pain, chronic pain after spinal surgery, previously denoted as Failed Back Surgery Syndrome, is localized in the back area, where the surgery took place, or projected into one or both limb as radicular pain2. A neuropathic pain component is present in about half of the patients2. The impact of chronic pain after spinal surgery on an individual’s health-related quality of life and its economic costs to society are considerable3. Direct consequences are visible in several domains among which chronic low back pain and/or leg pain, but also disturbed sleep, reduced participation, disability, high use of healthcare resources (e.g. use of opioids) and loss of employment4,5,6,7. Nevertheless, labelling all patients generically as suffering from failed previous surgery fails to incorporate the broad range of factors that may contribute to the condition and limits the understanding of this health condition8. Therefore, chronic pain after spinal surgery has recently been redefined as Persistent Spinal Pain Syndrome Type 2 (PSPS-T2) to indicate that patients experience chronic spinal pain, despite previous surgical involvement8.

Understanding what constitutes effective management strategies for PSPS-T2 patients remains challenging due to the complex underlying pathophysiology, the heterogeneity of underlying causes and symptoms9, and the need for more clinical data to support an evidence-based approach to treatment10,11. Treatment of chronic pain patients should be individualized (i.e. personalized treatment approaches) to provide long-term pain control with a reduction of costs and avoiding the less effective modalities12. Krames et al. proposed a holistic approach that accounts for multiple individual factors with the acronym S.A.F.E., in order to compare the Safety, Appropriateness, Fiscal neutrality, and Effectiveness of different treatment options13. A more recent study proposed to utilize levels of evidence for different treatment approaches during the evaluation of each individual patient to select the most effective, safe, appropriate, and fiscally neutral modality to treat patients with PSPS-T212. Moreover, the influence of individual goals and expectations, selection bias, ethical beliefs and technological innovations will inherently influence decision-making14. Despite the availability of a broad treatment arsenal, there is still an ongoing debate about efficacy, adverse events, indications and cost-effectiveness of the different treatment modalities for patients with PSPS-T215. Therefore, this systematic review and network meta-analysis will provide an overview of the current evidence for the possible therapeutic modalities for patients with PSPS-T2.

This systematic review reveals that studies towards treatment modalities for patients with PSPS-T2 mainly focus on neuromodulation (especially Spinal Cord Stimulation), and minimally invasive treatment options (predominantly epidural injections). To a lesser extent, conservative treatments (physiotherapy/cognitive training and medication) and reoperation are presented. Based on a network meta-analysis, neuromodulation, followed by conservative treatment options, seems to be the most effective treatment option to obtain pain relief. Yet, it is important to note that patients are considered for neuromodulation interventions only after conservative treatments have failed to provide satisfactory pain relief, while the most beneficial effects of conservative treatments are typically seen at earlier stages of the treatment pathway.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This systematic review was conducted according to the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses)16. The study protocol for this review was registered a priori in PROSPERO under the registration number CRD42022360160. For this systematic review, no Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained, since only data from published articles was used.

Search strategy

The search strategy was conducted using the following four databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Embase and Scopus from database inception to September 16th, 2022, with updated searches to December 18th, 2023. The research question was created according to the PICOS (Population-Intervention-Control-Outcome-Study design) framework17 to investigate the efficacy of current treatment modalities (Intervention/Control) for patients with PSPS-T2 (Population) in terms of pain (Outcome). As a study design, only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible (parallel and crossover trials). No limits were applied to this search strategy. The complete search strategy can be found in Supplementary Methods 1.

Eligibility criteria

Studies evaluating the efficacy of treatment options in patients with PSPS-T2 were eligible. Both studies with chronic pain patients (pain > 3 months18) and previous surgery at the neck (previously called Failed Neck Surgery Syndrome patients) or lower back (previously called Failed Back Surgery Syndrome patients) were included. Studies in children, participants with (sub)acute pain or studies in patients with PSPS Type I (no previous surgery) were excluded. All treatment options that are provided to patients with chronic spinal pain after previous spinal surgery could be included as the intervention. The comparators discussed in this review could include any surgical, medical, medicinal, paramedical or placebo intervention(s); regardless of therapy form, duration, frequency, intensity or setting used. Only RCTs (with parallel or crossover design), investigating the effect of several treatment methods on pain in PSPS-T2, were considered for inclusion. Any type of self-reported pain measurement tool was included. Studies reporting in languages other than English, Dutch or French were excluded. For studies with the same registration number or studies reporting results of the same study, only the primary publication was included with the longest follow-up duration within. In the case of parallel group RCTs with a crossover at a specified point where patients could switch the treatment group if preferred, only the results before the crossover were taken into account. Full eligibility criteria can be found in Table 1.

Study selection

After de-duplication in both EndNote X9 and Rayyan, two reviewers independently screened the title and abstract of all retrieved articles using the online software Rayyan. The same two reviewers independently performed the full-text screening. In case of conflicts at each stage, these were resolved in a consensus meeting with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

The following items, which were determined a priori, were extracted from each of the included studies: first author, year of publication, country, study design, sample size, patient demographics (mean age and sex), pain indication, type of interventions, pain measures, pain findings and interpretation. Data about functionality and health-related quality of life were also extracted, in case they were provided.

Considering the baseline similarities of pain intensity scores in included RCTs, post-intervention mean and standard deviation (SD) were directly extracted as outcome data from each of the articles. In case the necessary information could not be extracted adequately, the study authors were contacted by email to request it. When the median with first and third quartile or interquartile range were provided, the mean and standard deviation were calculated manually, according to formula’s provided by Wan et al. (2014)19. When SD posttreatment was not provided, the SD from baseline was taken as posttreatment value. Otherwise, the average of SD of other studies was imputed in case SD was not provided. In addition, if data were expressed only as a graph (rather than numerical data within the text), the software Engauge Digitizer 12.1 was used to extract it. For types of intervention, a classification was made into 5 distinct classes namely conservative treatment (includes physiotherapy, pharmacological therapy, rehabilitation, and intensive pain management programme), minimally invasive treatment (includes interventional techniques among which selective nerve root blocks, facet and sacroiliac joint infiltration/denervation, pulsed radiofrequency and epidural injection), neurostimulation, surgery (re-operation), and placebo/sham (when the intervention did not intend to be a pain management technique for PSPS-T2)20.

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer and checked for accuracy by another reviewer. Any discrepancies were discussed in a consensus meeting between both reviewers.

Risk of bias assessment

Since this systematic review only included RCTs, the revised Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB 2) was used to independently assess the methodological quality and risk of bias of all included studies21. This tool includes five domains: randomization process (1), deviations from intended interventions (2), missing outcome data (3), measurement of outcome (4), and selection of the reported results (5). Each study was judged as having low risk of bias, some concerns or high risk of bias for each domain separately and for overall judgement. The risk of bias assessment was independently performed by two reviewers. In case of any disagreements, they were discussed and resolved in a consensus meeting with both reviewers.

Statistics and reproducibility

A frequentist approach network meta-analysis was performed using the R package netmeta. Analyses were performed in RStudio (version 2022.07.2). As underlying assumptions, network consistency and transitivity between every indirect comparison were accepted by design. Transitivity suggests that the underlying true relative treatment effect of each comparison is the same across all, observed or not, comparisons, meaning that there are no systematic differences between the available comparisons other than the treatments being compared22. Consistency is the statistical manifestation of transitivity to the data, i.e. the statistical agreement between the direct and indirect comparisons23. Given the possibility of heterogeneity among studies, we choose the random-effects model for the meta-analysis. Standardized mean differences (SMD) with change score standardization were utilized as the summary measure to homogenize results from several pain intensity instruments. The network meta-analysis returned pairwise comparisons between all treatment modalities, rankings of the modalities using P-scores and assessed the probability that each modality is the best using rankograms with 1000 simulations24. P-scores measure the mean extent of certainty that a treatment is better than the competing treatments25.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Study selection

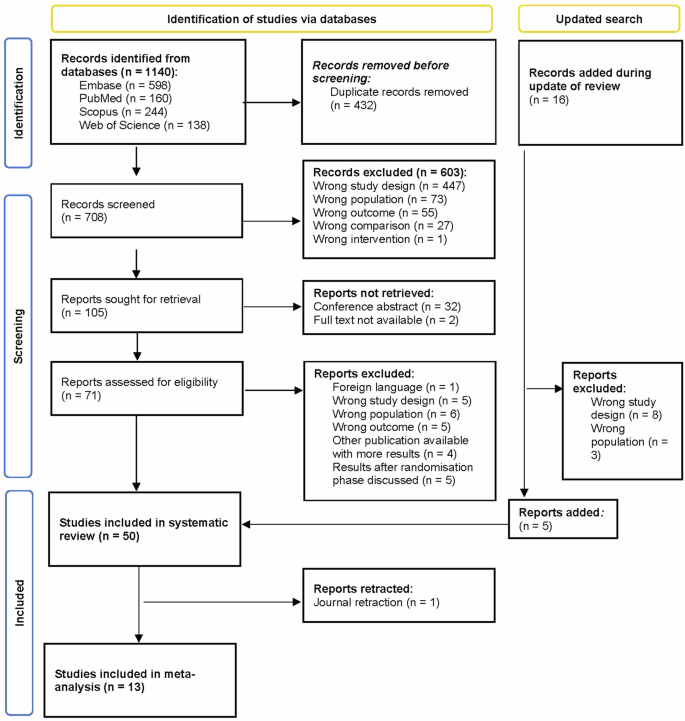

A total of 1140 articles were identified as potentially eligible through database search (Fig. 1). After removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 708 articles were screened. The percentage of agreement on title and abstract screening between both reviewers was 97.03% (21 conflicts). One hundred and five articles were eligible for full-text screening. Thirty-four articles were excluded because there was no full text available. After full-text screening (N = 71), 45 articles were included in this systematic review. The percentage of agreement on full-text screening between both reviewers was 84.76%. Reasons for exclusion based on full-text screening are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Five additional articles were included after an updated search, leading to a total of 50 articles included in the systematic review. One article was retracted from the Journal, leading to 49 articles in the systematic review. Fourteen articles could be included in the meta-analysis, whereby data from 13 studies was effectively used.

A total of 1140 articles were identified from Embase, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. After excluding 432 duplicates, 708 articles were screened on title and abstract. Of these, 105 were deemed suitable for potential inclusion, of which 71 effectively underwent screening on full text. After full-text screening, 45 articles could be included in the systematic review. Five additional articles were included after an updated search, leading to a total of 50 articles included in the systematic review. Fourteen articles could be included in the meta-analysis, whereby data of 13 articles could effectively be incorporated since these articles all contributed to 1 subnetwork. n number of studies.

Risk of bias

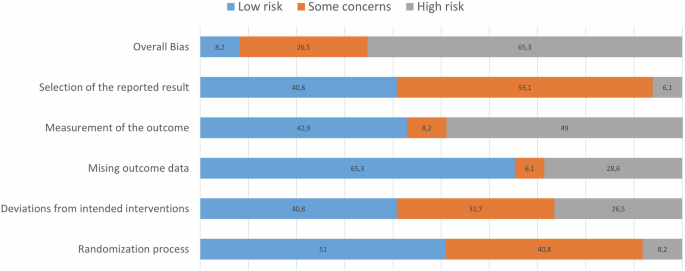

Risk of bias evaluation is presented in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2. In terms of overall bias, four studies (8.2%) revealed a low risk of bias11,26,27,28, 13 (26.5%) some concerns29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 and 32 (65.3%) revealed a high risk10,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72. The randomization process (domain 1) presented concerns mainly due to lack of describing allocation concealment until enrolment. The second domain, deviations from intended interventions, mainly posed concerns because the patients and/or investigators were not blinded. The missing outcome data (domain 3) was rated as low risk of bias for 65.3%, and caused high risk of bias for 28.6% since data was not available for (nearly) all patients. The fourth domain, measurement of outcome, was rated as high risk of bias in 49%, mainly due to lack of information about blinding of assessors and assessments that could be influenced if intervention is known. For the fifth and final domain (selection of the results reported), 53.1% was rated as some concerns most often due to the lack of a pre-specified analysis plan.

Fourty-nine articles are included in this assessment, whereby scores are presented on a percentage scale.

Study Characteristics

A complete overview of the characteristics of the included studies can be found in Supplementary Data 1. All included studies entailed patients with previous surgery in the lower back. The earliest studies included in this review were published in 1999 and the most recent studies in 2023. Pain was most frequently assessed with the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (n = 33), followed by the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) (n = 13). Other methods were the Verbal Pain Rating Scale (n = 2) and a summary VAS scale (n = 1). In terms of intervention, half of the studies (n = 25) investigated a neuromodulation technique as treatment option11,28,29,36,37,38,39,40,41,43,46,49,52,55,57,58,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71,72. Minimal invasive treatment options were also frequently evaluated (n = 16)30,31,32,33,34,35,42,45,48,50,51,53,54,59,60,61. Only two studies investigated a surgical approach10,70 and 6 studies focussed on conservative treatment options26,27,44,47,56,62. A placebo/sham was embedded in 11 studies11,27,37,38,39,52,58,64,65,66,67.

Narrative synthesis about the efficacy of treatment options for PSPS-T2

Studies discussing conservative treatment options (n = 6)

Two studies focused on physiotherapy or cognitive interventions44,47, while four studies compared different types of medication26,27,56,62. Positive effects were revealed with active treatment interventions44, preferably with the addition of cognitive behavioural tools47. Karahan et al. compared 4 different physiotherapy interventions, whereby pain relief was significantly greater in the isokinetic exercise programme and the dynamic lumbar stabilization exercise programme (programmes with feedback from a physiotherapist) compared to the home exercises programme and the control group44. An 8-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Therapy programme was also used as a treatment modality, compared with traditional care in a parallel study of Esmer et al.47. The Mindfulness group showed significant improvements in pain, pain acceptance and quality of life, and functional limitations relative to the traditional care group at 12 weeks of follow-up47.

The four remaining studies all compared different types of medication26,27,56,62 with conflicting evidence for Gabapentin, reportedly resulting in significant pain relief in two studies26,56 and one study with less convincing effects on pain27, one study with positive effects of Pregabalin26 and one study without back pain relief with Naproxen56. The study of Khosravi et al. compared Gabapentin at a starting dose of 300 mg/day and a maximum of 1800 mg/day after 6 weeks with Naproxen at a starting daily dose of 250 mg and a maximum daily dose of 1500 mg after 6 weeks56. A significant back pain decrease was found at a daily dose of 600 mg of Gabapentin, leg pain relief was reported with a daily dose of 1200 mg of Gabapentin. Patients who received Naproxen did not report back pain relief, and only temporary leg pain relief at a daily dose of 1500 mg. The study concluded that Gabapentin (with a maximum dose of 1800 mg/day) is more efficient than Naproxen at reducing both back and leg pain56. The efficacy of Gabapentin was also evaluated by Gewandter et al. who compared a 7-week extended-release Gabapentin with a 7-week placebo period in a crossover trial with 10-day washout period27. No differences were observed between both groups in terms of pain relief27. Al-Ameri et al. compared Pregabalin 75 mg twice daily with gabapentin 300 mg twice daily and observed that both groups demonstrated pain relief, however, superior pain relief was demonstrated with Pregabalin26. A study by Neumann et al. compared sublingual Buprenorphine/Naloxone with Methadone in 19 patients62. All patients demonstrated significantly improved 24-hour pain severity reportings, however, only patients receiving methadone reported significantly reduced current pain severity62.

Studies with minimal invasive treatment options (e.g., selective nerve root blocks, facet and sacroiliac joint infiltration/denervation, pulsed radiofrequency and epidural injection) (n = 16)

Sixteen studies focused on minimal invasive treatment options30,31,32,33,34,35,42,45,48,50,51,53,54,59,60,61, predominantly on epidural administrations. Adding dexmedetomidine31,48 and adhesiolysis34,42,51,60 to an epidural injection seem to be beneficial in most of the studies. The beneficial effect of adding other steroids is less clear59,61. The approach to conduct a minimal invasive procedure does not seem to alter pain relief53,54, nor does repeated administration30 or extended procedures45.

Two studies evaluated the beneficial effect of adding dexmedetomidine whereby both studies revealed significant effects of this drug on pain relief31,48, quality of life31, analgesic requirement48 and disability48. Three studies explored the added value of adhesiolysis whereby a significantly better effect was revealed in the group with adhesiolysis on pain and functional status in the study of Manchikanti et al.60, on pain and total analgesic requirements in the study of Rahimzadeh34, and on long-term pain relief in the study of Yousef et al.42. Similarly, the study of Chun-jing et al. evaluated the added value of percutaneous lysis of epidural adhesions with significantly better effects on pain reduction after 1 month and 6 months compared to an injection with dexamethasone51.

Two studies evaluated three different groups with each other50,61. Devulder et al. compared nerve root sleeve injections with local anaesthetic and adhesiolysis versus local anaesthetic and steroids versus local anaesthetic and adhesiolysis and steroids50. No differences were revealed between the three groups after 1 month, 3 months or 6 months50. Meadeb et al. evaluated sacrococcygeal injections with disruption (saline) versus glucocorticoids versus disruption and glucocorticoids, whereby no difference between the groups was revealed after 120 days61. After 30 days, the VAS score significantly improved in the glucocorticoid group compared to the disruption group61. Manchikanti et al. also evaluated the added value of steroids when providing caudal epidural injections with local anaesthetic59. In both groups, pain intensity scores significantly decreased over time, without a difference between both groups over a period of one year59.

Two studies evaluated the approach to conduct a procedure whereby Akbas et al. compared percutaneous epidural adhesiolysis and neuroplasty through a caudal, S1-foraminal or L5-transforaminal approach for injection of local anaesthetic, steroids and adhesiolysis without differences between the three groups54. A caudal versus transforaminal epidural steroid injection with local anaesthetic revealed a similar result, namely no difference between both groups53. Instead of the approach, one study evaluated the duration of a procedure, namely a 1 day versus 3 days epidural adhesiolysis whereby both groups revealed a significant pain and disability improvement45. Disability was significantly better in the group who received the procedure on 1 day at the 1-month visit. Additionally, Fredman et al. evaluated the effect of repeated epidural administration of Bupivacaine compared to repeated Saline administration after receiving a local anaesthetic on day 1 in both groups30. No differences were revealed between both groups30.

Rapčan et al. compared an epiduroscopy with mechanical adhesiolysis of the epidural fibrotic attachments with an epiduroscopy with mechanical adhesiolysis and adhesiolysis with hyaluronidase and corticosteroid administration35. Both groups significantly improved in terms of pain relief and disability after 6 months. After 12 months, only the group with mechanical lysis and drug administration improved with respect to pain relief. No difference was revealed between both groups35.

Intravenous infusion with 0.9% normal saline versus lidocaine 1 mg/kg in 500 ml normal saline versus lidocaine 5 mg/kg in 500 ml normal saline over 60 min were compared in a crossover study33. Pain intensity scores among the three groups did not differed33.

One study evaluated intrathecal trialling before starting a trajectory with intrathecal drug delivery, in which intrathecal catheter infusion with a mixture of Fentanyl and Bupivacaine was compared to saline, revealing significantly higher pain reductions in the Fentanyl/Bupivacaine group32.

Studies with neuromodulation (n = 25)

Only 5 studies did not include Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) in one of the treatment arms11,39,49,52,58. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation and auricular acupressure significantly decreased pain scores compared to sham/placebo applications52,58. Twelve studies focused on comparing different SCS paradigms with each other29,36,37,38,41,46,55,64,65,66,67,68, whereby more than 50% of the studies could not reveal significant differences between treatment paradigms29,36,41,55,64,66,68. Studies with a significant difference between stimulation paradigms pointed towards the efficacy of 10 kHz compared to tonic46, burst compared to tonic/placebo37, 5882 Hz stimulation compared to 1200 Hz, 3030 Hz and sham stimulation67, and high-density SCS compared to sham38. The type of material used (electrode, implantation and additional settings) did not result in significant differences in pain relief28,40,63,69. Combining several neuromodulation interventions seems to be beneficial to obtain pain relief43,72, as is providing neuromodulation techniques compared to a combination of conservative treatments and minimal invasive therapy options49,57,71.

Three studies compared high-frequency SCS (i.e. stimulation at 10 KHz) with low-frequency SCS (10–1500 Hz55, 40 Hz41 and 39.2–77.3 Hz46). Bolash et al.55 found that VAS pain decrease was significant for both groups and De Andres et al.41 reported a significant decrease in global average reduction of pain at 1 year follow-up similarly for both groups. In both studies, no significant difference between groups was found. Kapural et al. compared 10 KHz SCS with tonic SCS whereby they evaluated the number of responders, defined as ≥50% back pain reduction with no stimulation-related neurological deficit46. At 3 months, 84.5% of implanted 10 KHz patients were responders for back pain and 83.1% for leg pain, while 43.8% were back pain responders with tonic SCS and 55.5% for leg pain (significant difference between groups). The superiority of 10 KHz SCS for leg and back pain was sustained throughout 12 months46.

Other side-by-side comparisons were conducted between 30 Hz versus 1000 Hz29 and between placebo and sham SCS64. A crossover study of Breel et al.29 compared 9-day periods of SCS with 30 Hz versus 1000 Hz and reported a nonsignificant period effect. The difference in pain suppression between groups was also not statistically significant29. Hara et al. evaluated two 3-month periods of placebo SCS with two 3-month periods of burst SCS (40 Hz, 50% to 70% of paresthesia perception, 4 spikes per burst), whereby no between-group differences were revealed for pain intensity scores, nor for disability scores64.

More than two stimulation paradigms were tested in several trials36,37,65,66,67. Schu et al. compared SCS with burst, tonic (500 Hz), and placebo stimulation37. After 1 week, mean NRS score significantly decreased in the burst group compared to the other groups. Mean pain intensity scores were not significantly different between tonic and placebo stimulation. There were no differences in ODI categories between the three groups37. Tan et al. compared SCS with tonic, placebo, and intensity-modulated stimulation65. No conclusions regarding pain decrease between the groups were reported65. Sokal et al. conducted a crossover trial with 4 SCS paradigms, namely tonic SCS, 1KHz SCS, clustered tonic/burst SCS and sham SCS66. Significant reductions in pain intensity scores were revealed for the 4 stimulation paradigms66. Rigoard et al. evaluated tonic SCS versus high-frequency SCS (650-1200 Hz) versus burst SCS, each for 1 month36. No difference was revealed between the different waveforms36. Al-Kaisy et al. compared SCS with three different frequencies (1200 Hz versus 3030 Hz versus 5882 Hz), as well as sham SCS67. A significant difference in back pain was reported on the VAS for the SCS at 5882 Hz compared to the other groups. No significant difference was found between the three other groups (sham SCS, SCS with 1200 Hz at 180µs, SCS with 3030 Hz at 60µs) for back pain. For leg pain, no significant differences were found between the different groups67.

Two other studies used three stimulation paradigms with a randomization scheme for 2 of them38,68. Sweet et al. used conventional SCS, subthreshold high-density SCS (1200 Hz, 200µs pulse width) and sham SCS (stimulation at 0V), whereby the order of high-density SCS and sham SCS was different38. When receiving high-density SCS, a significant difference in pain scores compared to sham SCS was found38. Duse et al. first provided patients with a 7-day treatment with paraesthesia-based SCS, followed by a randomization between burst SCS and 1KHz SCS, after which patients crossed groups68. No significant superiority was found between groups. For both the burst group and the 1KHz group, significant pain relief on the NRS was reported68.

Four studies differed in type of materials between groups28,40,63,69. North et al. compared SCS delivered by a percutaneous electrode versus an insulated electrode (implanted with a minilaminectomy)63. At 1.9 years of follow-up, the insulated electrode resulted in a successful outcome (≥50% pain relief and patient satisfaction) in 83.3%, while the percutaneous electrode resulted in success in 41.6% of the patients. At 2.9 years of follow-up, no significant difference was found between success rates in both groups63. Rigoard et al. compared SCS with monocolumn programming versus multicolumn programming and found no significant difference between groups28. Al-Kaisy et al. compared SCS with anatomic lead placement (AP), versus paraesthesia mapping (PM)40. Both groups showed significant decrease in both back and leg pain on the VAS, but no significant difference between groups was found40. Beasley et al. compared SCS with automatic position-adaptive or manual stimulation69. The clinical outcomes on the VAS improved significantly from baseline to all follow-up time periods, regardless of using either automatic position-adaptive stimulation or manual stimulation69.

The added value of combining different neuromodulation techniques compared to SCS alone was evaluated by 2 studies43,72. Rigoard et al. compared the additional value of peripheral nerve field stimulation with SCS compared to SCS alone43. At 1 month, the group with add-on therapy showed significantly more back pain relief and a better disability score compared to SCS alone. At 3 months, a significantly greater back pain relief was revealed. No significant difference in leg pain relief could be found at 3 months between both groups43. Van Gorp et al. evaluated the add-on value of subcutaneous stimulation to SCS and found ≥50% back pain reduction in 42.9% of the patients with the add-on therapy compared to 4.2% in patients only receiving SCS72. At 3 months of follow-up, a statistically significant higher back pain reduction was revealed in the group who also received subcutaneous stimulation compared to SCS alone72.

Other neuromodulation interventions that were explored are Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (r-TMS)52, active magnetic back corsets and magnetic foot insoles39, pulsed electromagnetic field stimulation11 and acupressure58. Bursali et al. compared r-TMS at 5 Hz for 20 min daily (10 sessions) with sham r-TMS52. Both groups displayed improvements in VAS scores (follow-up for 3 months), whereas improvement in the sham group was limited to the first month. Significant improvements were achieved in disability, depression, sleep quality, and DN4 scores in the r-TMS group compared to the sham group52. Weintraub et al. conducted a study in which patients continually wore an active magnetic back corset and a magnetic foot insole for 24 h versus a sham magnetic back corset and sham magnetic foot insole39. No significant differences were observed between both groups39. Sorrell et al. conducted a 3-arm RCT with pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) at 38-µs pulse duration, PEMF at 42-µs and a sham device and found no significant difference between the three groups in terms of low back pain decrease11. Lim & Park compared auricular acupressure through patches for 6 weeks, each week consisting of 5 days therapy and 2 days of rest versus a placebo acupressure group58. After treatment, a significant time-by-treatment interaction effect was revealed with higher pain relief in the active acupressure group for both back and leg pain, and DN4 score58.

Three studies compared neuromodulation interventions to a combination of conservative treatments and minimal invasive therapy options49,57,71. In 2007, Kumar et al. compared conventional medical management (i.e. oral medications, nerve blocks, epidural corticosteroids, physical and psychological rehabilitative therapy, and/or chiropractic care) with SCS and conventional medical management in 100 patients57. Fifty percent pain relief in the legs was obtained by 48% in the SCS group and 9% in the conventional medical management group. Compared with the medical management group, the SCS group experienced significantly improved leg and back pain relief, quality of life, and functional capacity, as well as greater treatment satisfaction57. Rigoard et al. conducted a similar study whereby optimized medical management (could include treatments ranging from non-invasive treatments such as acupuncture, psychological/behavioural therapy, and physiotherapy to invasive treatments such as spinal injections/blocks, epidural adhesiolysis, and neurotomies) was compared to optimized medical management with multicolumn SCS71. At 6 months, 13.6% of the patients were responders (≥50% back pain reduction) in the group where SCS was added compared to 4.6% in the medical management group. The SCS group also improved on pain intensity, functional disability and health-related quality of life, while the medical management group only improved in health-related quality of life71. Eldabe et al. compared optimized medical management alone versus optimized medical management combined with subcutaneous nerve stimulation49. At 9 months, 33.9% of the patients were responders (≥50% back pain reduction) in the group where subcutaneous nerve stimulation was added compared to 1.7% in the medical management group, indicating the beneficial value of adding subcutaneous nerve stimulation to the treatment of PSPS-T2 patients49.

Studies with surgery (n = 2)

North et al. compared reoperation with SCS and found that at long-term follow-up, SCS was significantly more successful than reoperation70. Hamdy et al. compared the combination of percutaneous thermal radiofrequency neurotomy of the median branch of the facet nerve, percutaneous screw and rod spinal fixation (PSRF), and interlaminar epidural injection of triamcinolone with PSRF alone and found a significant pain-relieving effect for both groups over time10. The group who received the combination of treatments demonstrated significantly lower pain scores and lower disability compared to PSRF alone10.

Network meta-analysis

Of the 50 included studies in the systematic review, 14 were eligible for the network meta-analysis since they evaluated the efficacy of treatment options that belong to a different treatment class (conservative treatment, minimally invasive treatment, neurostimulation, surgery or placebo/sham) and provided mean pain intensity scores for each treatment group10,11,37,38,39,49,52,57,58,64,65,66,67,71. Two subnetworks were detected within the dataset without closed loops (Supplementary Fig. 1). Since only one study contributed to the first subnetwork in which surgery was compared with surgery/minimal invasive treatment, this subnetwork was removed from the analysis10. Therefore, data of 13 studies was used in the meta-analysis11,37,38,39,49,52,57,58,64,65,66,67,71 with a comparison between 4 interventions: neuromodulation, conservative treatment, conservative/minimal invasive treatment and placebo/sham. Placebo/sham consisted of the following interventions: sham SCS stimulation38,65,66,67, placebo SCS stimulation37,64, sham magnetic back corset and sham foot insole for 24 h39, sham r-TMS52, sham pulsed electromagnetic field therapy11, and auricular acupressure at helix 1 ~ 5 points58. Nineteen estimates were available for the comparison between neuromodulation and placebo/sham11,37,38,39,52,58,64,65,66,67, 4 for comparison between neuromodulation and a combination of conservative and minimal invasive options57,71 and two for comparison between neuromodulation and conservative treatment options49 (Supplementary Data 2).

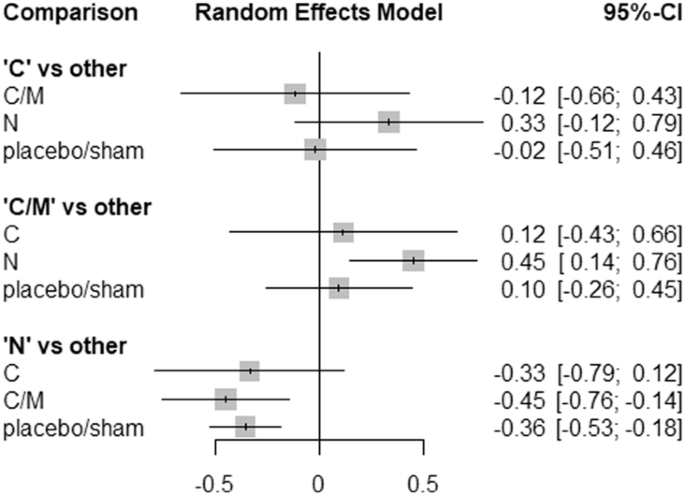

Comparisons of neuromodulation versus a combination of conservative and minimally invasive options resulted in SMD of 0.45 (95% CI from 0.14 to 0.76) for pain intensity, clearly favouring neuromodulation (z = 2.88, p = 0.004). Additionally, neuromodulation resulted in SMD of 0.36 (95% CI from 0.18 to 0.53) compared to placebo/sham (z = 4.03, p < 0.0001). Figure 3 presents the forest plot for comparison between treatment options for patients with PSPS-T2.

A random effects network meta-analysis was conducted with standardised mean differences as effect measures and 95% confidence intervals. Data from 13 articles is used in the meta-analysis. C conservative, M minimal invasive, N neuromodulation, S surgery.

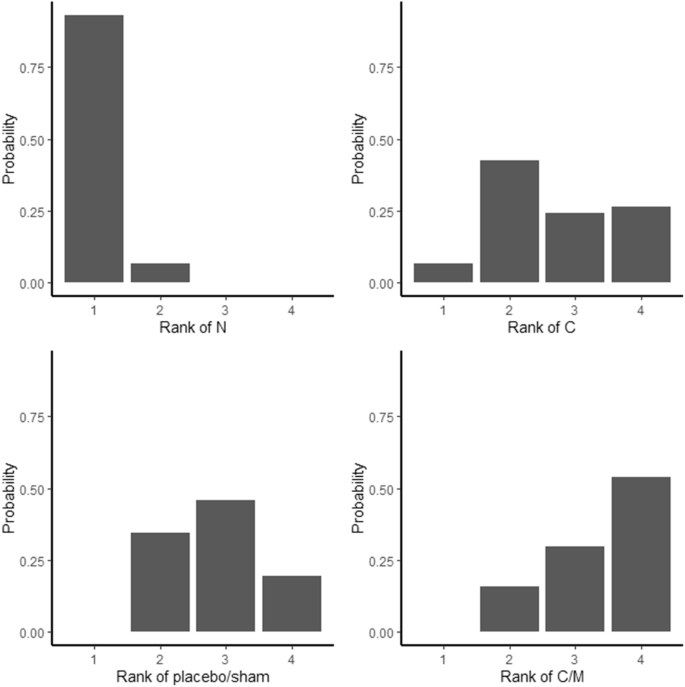

Treatment ranking resulted in P-scores of 0.975 for neuromodulation, 0.423 for conservative treatment options, 0.389 for placebo/sham and 0.212 for a combination of conservative and minimal invasive options, clearly pointing towards neuromodulation as most effective treatment (Fig. 4). This network meta-analysis demonstrated a considerable level of heterogeneity (I² = 77.5% (95% CI from 66.6% to 84.8%)). Design-specific decomposition of the Q statistic showed that the within-design heterogeneity can largely be tracked back to the comparison of conservative treatment versus neuromodulation and placebo/sham versus neuromodulation. Inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence within the network could not be estimated since none of the pairwise comparisons relied on a combination of direct and indirect evidence. Statistical tests for funnel plot asymmetry (Egger’s test p = 0.94) suggest low risk of publication bias (Supplementary Fig. 2). Meta-analyses for disability and health-related quality of life are presented in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Rankogram is based on 1000 simulations. Data from 13 articles is used in this analysis. C conservative, M minimal invasive, N neuromodulation, S surgery.

Discussion

This systematic review evaluated the different treatment options for patients with PSPS-T2, whereby 51% of the studies evaluated neuromodulation techniques, 32.7% minimal invasive treatment options, 12.2% conservative therapies and 4.1% re-operation. The network meta-analysis favoured neuromodulation above placebo/sham options. Additionally, compared to a combination of conservative and minimal invasive options, neuromodulation resulted in a significant improvement of pain intensity. Treatment ranking denoted neuromodulation as most effective for patients with PSPS-T2, followed by conservative treatment options.

In 2020, a revision of the analgesic ladder was proposed for patients with chronic non-cancer pain, in which a four-step ladder is described73. This ladder incorporates integrative therapies at each step to reduce or completely omit the use of opioids. Additionally, interventional therapies are proposed as step 3 in the ladder, before upgrading to strong opioids in case of unsatisfying pain relief with non-opioids and weak opioids73. Neuromodulation, as interventional therapy in the revised analgesic ladder, was ranked first to obtain pain relief in our network meta-analysis, potentially further opening the avenue towards earlier implementation of neuromodulation in the care pathway. In this review, two types of interventions were categorized as conservative treatment options namely physiotherapy and medication. The former pointed towards the use of physiotherapy sessions44 in combination with cognitive treatment options47, while the latter pointed towards the use of Gabapentin26,56. A recent narrative review stated that conservative treatments, consisting of pharmacologic therapy, physical therapy, and psychotherapy, should always be attempted first due to their good safety profile in patients who do not require urgent surgical intervention74. Patients with chronic pain after spinal surgery may well suffer from central sensitization (CS), characterized by altered central pain processing75,76, whereby proposed treatment options for CS are medication, pain neuroscience education, cognitive behavioural therapy and exercise therapy77,78, all completely in line with the conservative treatment options as revealed by our review. In terms of medication, a recent study evaluated electronic health records from 164,709 patients with PSPS-T2. Prevalences of prescription of neuropathic mood agents and opioids were 78.5% and 87.9%, respectively, in 202379. Remarkably, our review pointed towards the efficacy of Gabapentin, however, none of the included studies evaluated opioids.

During the last two years, the lack of robust scientific evidence for the efficacy of neuromodulation in the treatment of PSPS-T2 was extensively discussed in two Cochrane reviews80,81, resulting in a series of letters that highlighted limitations with the interpretation of findings from the Cochrane reviews82,83,84,85. The current network meta-analysis revealed the efficacy of neuromodulation compared to placebo/sham and a no significant difference between conservative treatment options and neuromodulation, a result that is in line with the comparative effectiveness study of Dhruva et al. in which no significant difference was revealed between conservative management and neuromodulation on opioid use or nonpharmacological pain interventions86. Yet, this result should be carefully interpreted since patients who are eligible for neuromodulation very often present with a different stage of PSPS-T2 after failed responses to conservative treatment options compared to those who are included in studies evaluating conservative treatment options87. The development of network meta-analyses has allowed more insights in the available evidence with the estimation of metrics for all possible comparisons in the same model, thereby simultaneously gathering direct and indirect evidence, and as such providing complementary knowledge to the existing reviews from a different perspective.

It is remarkable that there is a relative paucity of studies suitable for this network meta-analysis given the high societal and fiscal cost of PSPS-T2. The majority of studies explored treatments that could be allocated to the same class according to the classification used in the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method20. A broad variety of different techniques was found within each class, wherefore these are only described in a narrative way and no separate meta-analyses were conducted within each class, which serves as the first limitation of this work. Moreover, in the meta-analysis, a broad variety of interventions is clustered into the classes, wherefore results should be interpreted with caution. Secondly, the main analysis was primarily focused on pain relief. Pain intensity was extracted as numerical output, whereby no separate analyses were conducted for studies that reported on 30% or 50% pain relief. Meta-analyses were presented on disability and health-related quality of life, however, only a limited number of articles could be included, wherefore these analyses are only starting points for future updates. Finally, it is highly likely that patients undergoing neuromodulation or other interventional pain techniques are those who failed to benefit from conservative therapies88 thereby they likely represent a more refractory group with longer durations of pain thereby limiting the value of the comparison of these therapy groups.

Further research (both primary and comparative) of treatment options should occur as we believe that we have a baseline sampling of data but that the full picture is far from being revealed. We would commend future researchers to focus on ensuring their studies have a low risk of bias to ensure higher precision and confidence of observed results. Additionally, we strongly advocate for physician-initiated trials. This analysis would be regarded as a living document and suitable to be upgraded as subsequent trials are conducted and published in the peer reviewed literature.

This network meta-analysis revealed that neuromodulation, followed by conservative treatment approaches, seem to be the most effective treatment options to obtain pain relief in patients with PSPS-T2, based on direct and indirect pairwise comparisons from available randomised controlled trials. For neuromodulation, beneficial effects of SCS were revealed as well as the added value of a combination of multiple neuromodulation techniques. It should be noted that patients are only considered for neuromodulation interventions after failing to obtain satisfactory pain relief with conservative treatment options. In terms of SCS stimulation paradigm, there is still a lack of consensus. Conservative approaches entail physiotherapy sessions with cognitive elements as well as pharmaceutical approaches with neuropathic mood agents. The beneficial effects with conservative treatment approaches are more likely observed at earlier stages in the treatment pathway. Despite the lower treatment ranking of minimal invasive treatment options, a substantial proportion of studies (32.7%) explored the efficacy of different types of epidural infiltration with beneficial effects of adding dexmedetomidine and performing adhesiolysis during this procedure.

Responses