TRPML1 ion channel promotes HepaRG cell differentiation under simulated microgravity conditions

Introduction

One of the biggest problems for human beings in space exploration and future space colonization is microgravity, which often leads to unusual phenomena and behaviors3. For example, human bone density and muscle mass can decrease significantly4,5. However, the research on the adverse effects of microgravity on human beings is very limited. One of the core bottlenecks is the lack of a real microgravity environment in the laboratory; thus, simulated microgravity clinostat methods were created to study how gravity change affects cell proliferation and differentiation, as well as organismal development and homeostasis, which is literally called microgravity effects simulation. The basic principle of clinostat methods is to continuously alter gravity orientation by rotating around a horizontal or biaxial axis, thereby preventing cells from perceiving a constant direction of gravity. The so-called microgravity effects simulation actually reflects the interference or nullification of the cell’s perception of gravity direction, whether these effects are equivalent to real microgravity effects and whether the underlying mechanisms are the same still need to be further investigated. Clinostat methods provide a specific way to study the gravity perception of cells. So far, various types of clinostat have been used for “microgravity effect simulation” research6,7,8,9. Thus, the RFC is a useful tool to detect the effect of simulated microgravity on cell fate and related molecular mechanisms.

The liver is a central organ for numerous physiological processes such as body energy metabolism, detoxification, and immunology6. Therefore, stem/progenitor cells in the developing liver have been thoroughly studied to explore how they can be differentiated into functional hepatocytes. Hepatic differentiation is a complex process that involves four distinct stages for stem cells (stemness maintenance (STEM), definitive endodermal lineage (DE), precursor hepatocytes (Pre-H), and hepatocyte-like cells (M-H)), each characterized by specific cellular and molecular changes7. The key markers associated with the stem stage include OCT-4 and NANOG; at the DE stage, the two DE biomarkers SOX17 and CXCR4 were sound expression; the critical markers associated with Pre-H stage are AFP and SOX9; at the M-H stage, the two hepatic biomarkers ALB and CK18 were uniformly distributed within the cells and presented throughout the entire cells7,8. Because human hepatic stem cells are relatively difficult to obtain and their growth and differentiation rates are much slower under cell culture conditions, several cell lines were alternatively used to study the differentiation process of human hepatic stem cells. Among them, HepaRG cells exhibit many of the same characteristics as primary human developing hepatocytes. It can differentiate into both well-differentiated hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs) that resemble primary human hepatocytes (PHH), and biliary epithelial cells (cells lining the bile ducts) under defined culture conditions9. Therefore, HepaRG cells have been extensively used as an in vitro model for studying drug metabolism, cell differentiation, and liver diseases10. It’s known that physical forces such as substrate stiffness and shear stress have been shown to play a critical role in stem cell differentiation. Whether hepatic stem/progenitor cell differentiation responses to gravity change is still largely unknown.

Cells can adapt to the changes caused by physical forces by activating diversity of mechanical signaling pathways, thereafter affecting the morphological appearance and biological functions of cells11. Mechanoreceptors on cell membranes are capable of detecting and transmitting mechanical signals like pressure, stretch, and vibration into biochemical signals for further processing and interpretation12, finally regulating a wide range of cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and gene expression11. Until now, hundreds of mechanical sensors have been identified, and they play an essential role in various physiological processes, such as touch sensation, balance and proprioception, cardiovascular regulation, and pain perception13. For example, mechanosensitive ion channels, such as Piezo and TRP channels, are open in response to mechanical stimuli, allowing ions to flow across the cell membrane to initiate downstream signaling cascades14; mechanical forces can promote cytoskeleton remodeling and regulate gene expression by activating the adhesion protein (focal adhesion kinase, FAK)15. Thus, understanding the properties and roles of mechanoreceptors is essential for elucidating how cells sense and adapt to their mechanical environment and developing new approaches for diagnosing and treating mechanical-related diseases.

MCOLN1/TRPML1 is one of the transient receptor potential (TRP) channel family members, primarily localized on the endosomal and lysosomal compartments of cells, and plays a crucial role in controlling membrane trafficking, lysosomal biogenesis, autophagy, etc16. It is a large protein consisting of 580 amino acids and possesses 6 transmembrane domains, an intracellular N-terminal domain, and a C-terminal domain17. The activity of TRPML1 is stimulated by PI (3,5) P2 whose synthetization depends on Vac14 and PIKfyve18. TRPML1 is a nonselective cation channel that conducts calcium ions across the lysosomal membranes to facilitate membrane trafficking between endolysosomal compartments and plasma membranes19. In addition, it also promotes the fusion and maturation of endosomes with lysosomes, enabling the degradation of internalized macromolecules and the recycling of membrane proteins20. Moreover, as a calcium-permeable channel, TRPML1 modulates various calcium signaling pathways, including those involved in cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis17,21. Gravity change may cause mechanical signal responses at different levels, what role TRPML1 will play in cell’s gravity perception is still totally unknown.

In the article, the results show that the differentiation degree of HepaRG cells could be significantly enhanced under simulated microgravity effects conditions created by using RFC. Mechanically, simulated microgravity effects increase the content of PI (3,5) P2 through remodeling the cytoskeleton, which in turn activates TRPML1 to increase the calcium flux of lysosomal, finally promoting Wnt/β-catenin pathway-dependent cell differentiation. Our results disclosed a mechanical-biological coupling regulation mechanism that how simulated microgravity effect affects hepatic differentiation, which provides scientific foundations for embryonic liver development under simulated microgravity effect conditions.

Methods

The rotating flat chamber (RFC)

The Rotating Flat Chamber (RFC) is a type of clinostat, which mainly comprises cell culture chambers rotating around the horizontal axis, a motor, and other related components. Figure 1A shows the photography of the RFC designed and built by the Institute of Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China). The internal dimension of a single chamber is 60 mm in length, 20 mm in width and 3 mm in height. The area of cell culture substrate in the chamber is approximately 12 cm2. The volume of the chamber is about 3.6 ml. The RFC was set at a rate of 10 rpm/min, the minimum and maximum rotation radii (at the centerline and the edges in the width direction of the substrate) are 10.2 mm and 14.3 mm, respectively. The range of centrifugal force is from 1.1 × 10−³ g to 1.6 × 10−³ g. The HepaRG cells were seeded in the chambers of RFC and then rotated for 3 days to differentiate. All the culture chambers were filled with William’s E medium without bubbles to avoid the impact of shear force on HepaRG cells. The images of the cells were taken on an inverted microscope.

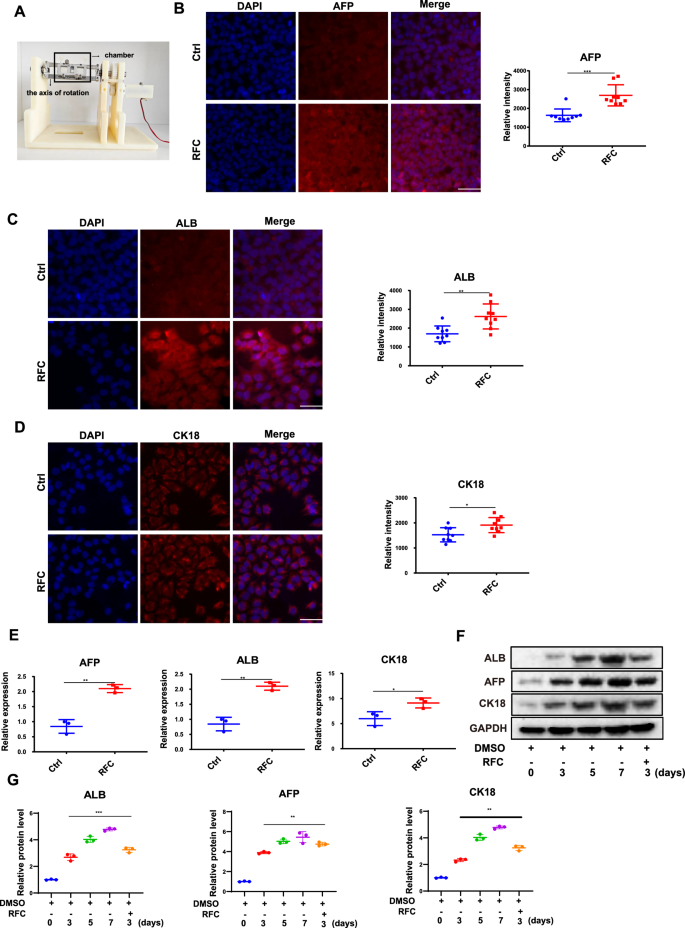

A The schematic of rotating flat chamber (RFC) device. B Immunofluorescence staining of AFP (red) and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells incubated without or with RFC (10 rpm/min) for 72 h as assessed by confocal imaging. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD (n = 9) by Student’s t-test. C Immunofluorescence staining of ALB (red) and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells incubated without or with RFC (10 rpm/min) for 72 h as assessed by confocal imaging. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD (n = 9) by Student’s t-test. D Immunofluorescence staining of CK18 (red) and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells incubated without or with RFC (10 rpm/min) for 72 h as assessed by confocal imaging. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD (n = 9) by Student’s t-test. E The RT-qPCR analysis for AFP, ALB, and CK18 mRNA levels in HepaRG cells, without or with RFC. Mean ± SD (n = 3) by Student’s t-test. F Western blot analysis and quantification (G) of the protein levels of ALB, AFP, CK18 in HepaRG cells under normal gravity conditions for 3–7 days or under cAGO conditions for 3 days. Mean ± SD (n = 3) by ANOVA.

Mechanical stretching and E₂

Mechanical stretching experiments were conducted following the protocol outlined in our previous study22,23, the custom-designed cell-stretching apparatus exhibit in the paper to induce stress in vitro22. HepaRG cells were seeded on gelatin-coated polydimethylsiloxane membranes (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), with an active area measuring 40 × 20 mm² (length × width) and a thickness of 3 mm. The HepaRG cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 10³ cells/cm² to evaluate cell morphology. After a 12–24 h culture period, the cells were subjected to uniaxial cyclic stretching (CS) at 0.1 Hz with 10% elongation, applied for 24 h. Non-stretched HepaRG cells cultured on gelatin-coated polydimethylsiloxane membranes served as the control group. The viable cells from each group were collected for protein analysis and mRNA detection.

Cell culture and hepatic cell differentiation

The HepaRG cells were purchased from Biochemistry and Cell Biology (Shanghai, China) and cultured in William’s E medium (ThermoFisher Scientific, Hamburg, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. HepaRG cells were differentiated into hepatocyte‐like cells (HLCs) by adding 2% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) into the medium.

CCK8 assay

The CCK8 assays were performed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Beyotime, Beijing, China) according to the instructions of the manufacturer24. Briefly, the HepaRG cells were cultured in a 96-well plate (104 cells/well), and DMSO or the indicated concentration (20 nM to 20 μM) of 206 compounds of mechanical receptor-sensitive inhibitors (3607-1/3607-2) (MedChemExpress, Guangdong, China) was added to each well, respectively. After incubation for 24 h, 10 μl CCK8 reagent was added into each 96-well plate and then incubated for 45 min at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The cell viability was measured at the 450 nm wavelength by microplate reader (ThermoFisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The HepaRG cells were added with the compounds for 72 h at a 10 rpm/min RPM device and then washed 3 times with PBS, digested with trypsin, and collected. Total RNA extracted by Trizol (Life Technologies, USA) was performed as previously described25. Reverse transcription (RT) was conducted to convert RNA to cDNA using an M5 HiperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Mei5bio, MF309-05) and oligo-dT primers. RT-qPCR was administered on the Light Cycler (Bio-Rad, USA) and normalized to GAPDH as control. Related primes were listed in Supplementary Table 1. The 2-ΔCycle Threshold (2-ΔCT) method was used to analyze all the results.

Western blotting

The Cell lysate was extracted using NETN lysis buffer (20 mM Tris- HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40 and 1% PMSF). Protein quantification was conducted using the BCA Protein Assay (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Extracts proteins were loaded into SDS-PAGE and then transferred to the PVDF membrane (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). The samples were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h, then primary antibody were incubated overnight at 4 °C; membranes were washed and then incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. The protein bands are visualized using an ECL reagent (Mei5bio, Beijing, China) and detected using an imaging system (BIO-RAD, State of California, USA). Antibodies used in this study were as follows: AFP (Proteintech, 14550-1-AP), ALB (Proteintech, 16475-1-AP), CK18 (Proteintech, 10830-1-AP), TRPML1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-398868), VAC14 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-271831), F-actin (ThermoFisher, A30107), β-cantein (Proteintech, 51067-2-AP), FAK (ABclonal, A11131), β-actin (Proteintech, 81115-1-RR), FN1 (ABclonal, A12932), FN1 (ABclonal, A12932), VIM (ABclonal, A19607), α-SMA (Proteintech, 14395-1-AP), GAPDH (Proteintech, 60004-1-Ig), and all the Primary antibodies were at 1:1000 dulution.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection and plasmids transfection

The HepaRG cells were incubated overnight to reach approximately 50–70% confluence; the siRNA (siTRPML1: sense, 5’-CGUGAUAAAGAAGUAAGCGTT-3’; anti-sense, 5’-CGCUUACUUCUUUAU-ACGTT-3’) in the antibiotic-free William’s E medium were mixed with Lipo2000 (Life Technologies, USA) in each plate according to the manufacturer’s instructions26. shRNA primes are listed in Supplementary Table 2. The experimental method is described above.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for 15 min at room temperature and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for 30 min. To minimize the nonspecific binding of antibodies, samples were incubated with 1% BSA (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for 1 h. Then, samples were incubated with the primary antibody overnight at 4 °C and washed 3 times with PBS. The secondary antibody was added to the samples at 37 °C for 1 h. The nucleus was counterstained with Hoechst, and samples were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany).

Ca2 + analyzing

The flow cytometry (FCM) and microplate reader were used to detect Ca2 + imaging according to protocol27. Briefly, a single cell suspension at 1 × 106 cells/ml was prepared in a physiologic loading buffer. And 2 μM Fluo-4 AM (BD biosciences, New York, USA) was added to the samples for 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were then isolated and prepared for analysis. Fluorescence intensity was measured at λExcitation 494 nm and λEmission 506 nm.

Atomic force microscope (AFM)

Force indentation measurements for hydrogels are performed by using an AFM (MFP-3D, Asylum Research) with a colloidal probe. The AFM is set up on an inverted microscope (IX71, Olympus) equipped with an EMCCD camera (Ixon3, Andor). The colloidal probe consists of a glass sphere of radius R (≅5 µm), which is glued on the front end of a rectangular cantilever beam (NSC35/Pt, MikroMasch) featuring a spring constant of 0.2 N/m. The AFM measurements were carried out in contact mode, and a constant loading speed v = 10 μm/s and the measured force-distance curves were recorded and fitted with Hertz model (text{F}=frac{4}{3(1-{{rm{v}}}^{2})})E({text{R}}^{0.5}{delta }^{1.5}) to calculate the Young’s modulus E28. All the force measurements were made at a temperature of ∼37 °C, which is monitored and maintained by a local temperature control inside the fluid chamber.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism. Error bars represent the SD of independent experiments or independent biological samples. The numbers of independent experiments or biological replicate samples and P-values (n.s. not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01) are provided in individual figures, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Simulated microgravity effects (cAGO) promote the differentiation of HepaRG cells towards HLCs

Previous studies have demonstrated that HepaRG cells can differentiate into HLCs with morphological characteristics of hepatic cells induced by DMSO29. To further validate the effect of DMSO treatment on HepaRG cell differentiation, flow cytometry assay was used to quantify the differentiation efficiency of HepaRG cells after 3-day DMSO exposure. As shown in Fig. S1A, B, the CK18 fluorescence intensity in DMSO-treated HepaRG cells was much higher than that in the control group. To explore the effect of microgravity on the differentiation of HepaRG cells, the RFC device was used to simulate microgravity and examined if simulated microgravity alters the differentiation degree of HepaRG cells upon DMSO induction for 3 days. As shown in Fig. 1B–D, immunofluorescence was conducted to detect the biomarkers of hepatic cell differentiation, and the results showed that the fluorescence intensity of APF, ALB, and CK18 were all markedly increased under simulated microgravity effects conditions, compared to the normal gravity group. To further determine the effect of the simulated microgravity, RT-qPCR and western blot assay were conducted to detect the expression levels of the three differentiation biomarkers. Similarly, the mRNA levels of APF, ALB, and CK18 were significantly increased in the presence of simulated microgravity (Fig. 1E, F). Flow cytometry results showed the expression level of CK18 was increased in the microgravity group compared to the normal group (Fig. S1). As shown in Fig. 1F, G, the protein expression levels of ALB, AFP and CK18 were significantly increased upon DMSO treatment in a time-dependent manner under normal conditions; meanwhile, RFC condition further increased the content of ALB, AFP, and CK18 at 3-day DMSO treatment, which almost reaches the content of 5-day DMSO treatment based on quantitative analysis. These results indicate that simulated microgravity effects promote the differentiation of HepaRG cells towards HLCs.

Screening of gravity-sensitive mechanoreceptors in HepaRG cells

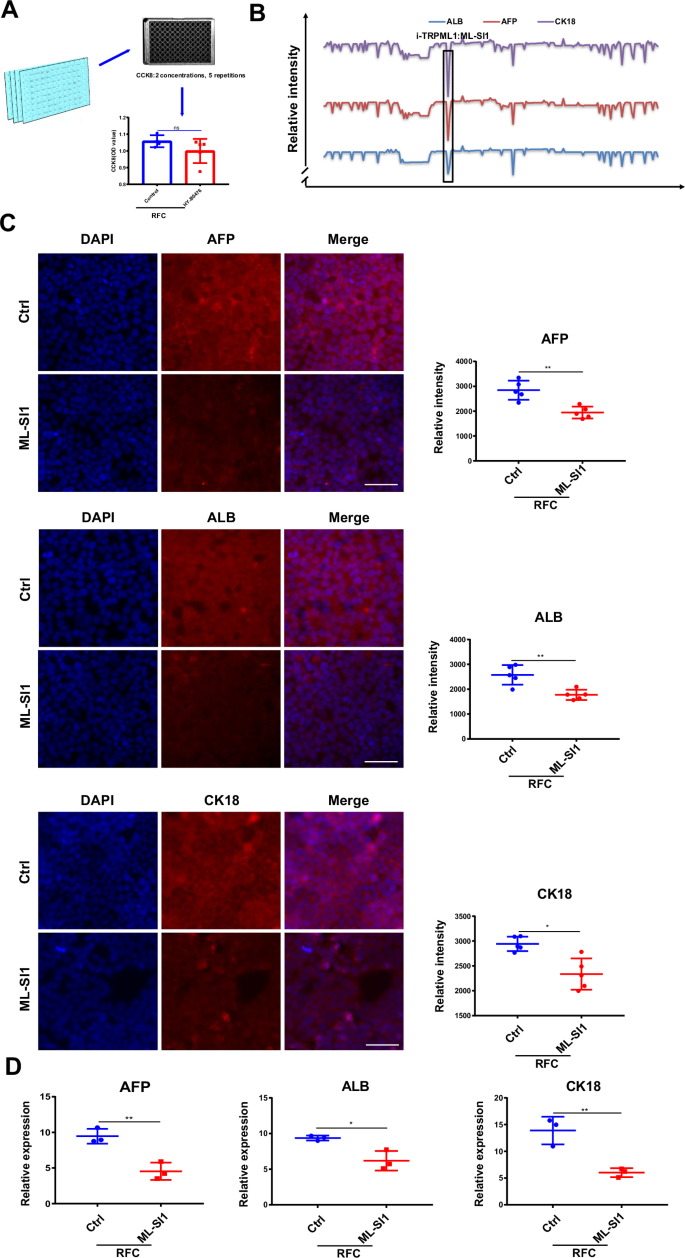

To explore the molecular mechanism of simulated microgravity-promoted HepaRG cell differentiation under RFC conditions, the mechanoreceptors compound library, which consists of 206 mechanical receptor-sensitive inhibitors, was used. CCK8 assay was conducted to define the nontoxic concentration of each mechanical receptor-sensitive inhibitor before further screening, as the experimental schematic diagram shows (Fig. 2A). To identify which mechanoreceptor plays a key role in regulating HepaRG cell differentiation, AFP, ALB, and CK18 were detected as the differentiation indexes. With high-content assays, ML-SI1, targeting TRPML1, turned out to be the most significant candidate that affected cell differentiation under RFC conditions (Fig. 2B). The results were further validated by immunofluorescence and RT-qPCR experiments (Fig. 2C, D). Combined, these results demonstrated that inhibiting TRPML1 with ML-SI1 effectively abrogated simulated microgravity-induced HepaRG cell differentiation.

A Schematic drawing of the screen for the concentrations of 206 mechanical receptor inhibitors. B Schematic drawing of the effect of 206 mechanical receptor inhibitors on cAGO-induced expression of the differentiation index, AFP, ALB, CK18. C Immunofluorescence staining of AFP, ALB, CK18 (red), and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells incubated without or with ML-SI1 (2.5 µM) for 72 h under RFC conditions. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD (n = 5) by Student’s t-test. D The RT-qPCR analysis for AFP, ALB, and CK18 mRNA levels in HepaRG cells without or with ML-SI1 (2.5 µM) under RFC conditions. Mean ± SD (n = 3) by Student’s t-test. The data are based on three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

TRPML1 is a gravity-sensitive receptor

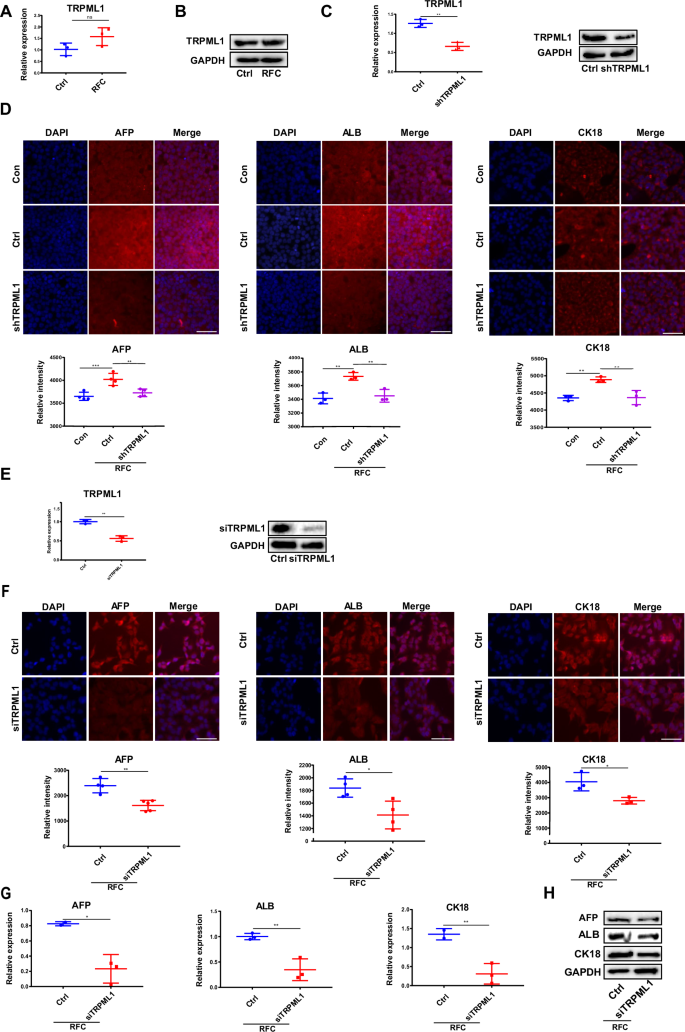

To further elaborate on the decisive role of TRPML1 in simulated microgravity-promoted HepaRG cell differentiation, RT-qPCR and western blot assays were conducted to detect the expression of TRPML1 in the presence of simulated microgravity. As shown in Fig. 3A, B, simulated microgravity had no significant effect on the mRNA and protein levels of TRPML1. In addition, when the endogenous TRPML1 was knocked down using its specific shRNA (Fig. 3C), the protein expression levels of AFP, ALB, and CK18 were also significantly decreased following the application of simulated microgravity (Fig. 3D). Moreover, similar to the results from shRNA, the protein and mRNA levels of AFP, ALB, and CK18 under simulated microgravity conditions were also markedly attenuated when the content of TRPML1 was knocked down by its siRNA (Fig. 3E–H). Collectively, these findings further demonstrated that TRPML1 plays a critical role in regulating simulated microgravity-induced hepatic differentiation. Moreover, stretch assay was used to test whether the activation and subsequent effects of TRPML1 are indeed specific to microgravity, or a general response to other stimuli. As shown in Fig. S2A, mechanical stretch could also promote the differentiation of HepaRG cells, as evidenced by the increased protein levels of AFP, ALB, and CK18. However, both knocking down TRPML1 or inhibiting its activity by ML-SI1 had no effect on stretch-induced HepaRG cell differentiation (Fig. S2A, B).

A The RT-qPCR analysis for the mRNA level of TRPML1 in HepaRG cells without or with RFC (10 rpm/min) for 72 h. Mean ± SD (n = 3) by Student’s t-test. B Western blotting analysis for the protein content of TRPML1 in HepaRG cells incubated without or with RFC. C The RT-qPCR and western blotting assays were conducted to analyze the transfection efficiency of shTRPML1. Mean ± SD (n = 3) by Student’s t-test. D Immunofluorescence staining of AFP, ALB, CK18 (red), and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells transfected without or with shTRPML1 (2.5 µM) for 72 h, under RFC conditions or not (Con: the undifferentiated group, the other groups: differentiated with DMSO). Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD (n = 5) by ANOVA. E The RT-qPCR and western blotting assays were conducted to analyze the transfection efficiency of siTRPML1. Mean ± SD (n = 3) by Student’s t-test. F Immunofluorescence staining of AFP, ALB, CK18 (red) and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells transfected without or with siTRPML1 (2.5 µM) for 72 h under RFC conditions. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD by Student’s t-test. G The RT-qPCR analysis of AFP, ALB, CK18 in HepaRG cells transfected without or with siTRPML1 (2.5 µM) for 72 h under RFC conditions. Mean ± SD by Student’s t-test. H The Western blot analysis of AFP, ALB, and CK18 in HepaRG cells transfected without or with siTRPML1 (2.5 µM) for 72 h under RFC conditions. Mean ± SD by Student’s t-test. The data are based on three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Calcium flux elevation mediates TRPML1-dependent differentiation

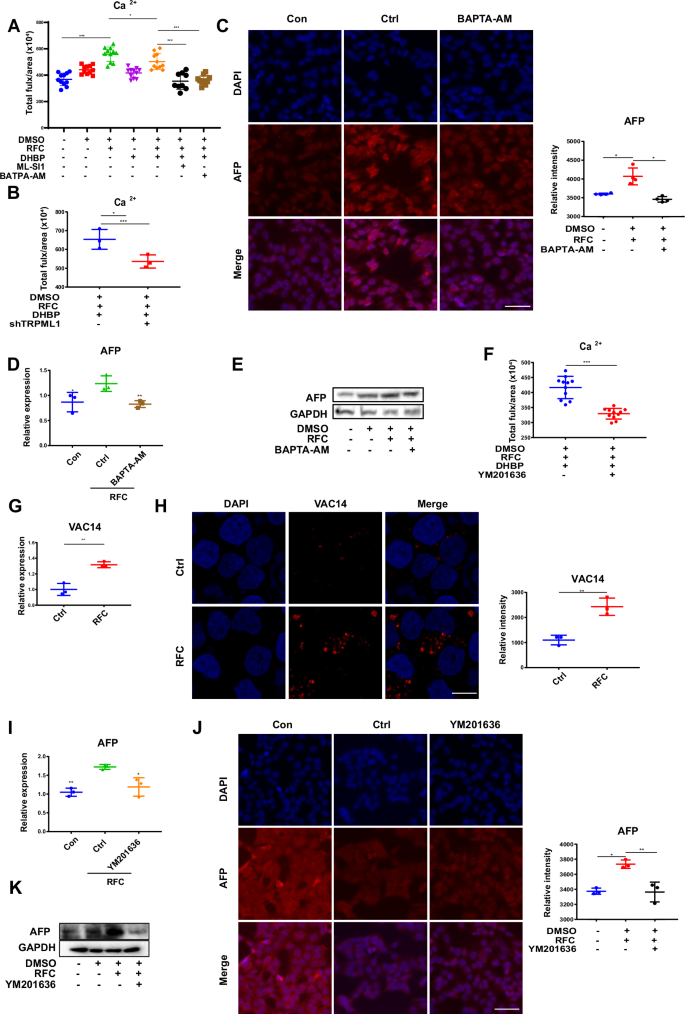

TRPML1 is a cation channel predominantly located on the lysosomal membrane that releases Ca2+ for activating calcium signaling pathways30. Thus, whether lysosomal calcium flux mediates simulated microgravity effects-triggered differentiation in HepaRG cells was detected. Dihydroxybenzophenone (DHBP), which can block calcium release from the ER but does not inhibit cell death31, was used to observe the effect of lysosomal calcium flux. As shown in Fig. 4A, RFC effectively increased lysosomal calcium flux after DMSO induction; meanwhile, similar to the specific Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM, ML-SI1 pretreatment could effectively decrease this phenomenon. In addition, knocking down TRPML1 with its shRNA obtained similar results (Fig. 4B), indicating that TRPML1 is indispensable for simulated microgravity-induced lysosomal calcium flux in HepaRG cells. To examine if calcium flux was required for simulated microgravity-triggered cell differentiation, the expression levels of the differentiation marker AFP were detected when calcium flux was blocked. As shown in Fig. 4C–E, the mRNA and protein levels of AFP in the presence of simulated microgravity were significantly reduced when cells were pretreated with BAPTA-AM, indicating that calcium flux contributes to simulated microgravity-induced differentiation in HepaRG cells. Additionally, there was no significant difference in calcium release in the cells of control group or TRPML1-depleted cells when under stretch condition (Fig. S2C).

A DMSO-differentiated cells were pretreated with DHBP (an inhibitor of endoplasmic reticulum calcium release), ML-SI1 (a TRPML1 inhibitor) or BAPTA-AM (a calcium chelator) for 6 h before under RFC conditions, thereafter the total calcium ion (Ca²⁺) flux was determined by Flow cytometry analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. B The effects of shRNA for TRPML1 on calcium flux in HepaRG cells (DMSO was used to induce differentiation) under RFC (10 rpm/min) for 72 h. Mean ± SD by Student’s t-test. C Immunofluorescence staining of AFP (red) and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells pretreated without or with BAPTA-AM (2.5 µM) under RFC or not. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD by ANOVA. D The RT-qPCR analysis for mRNA levels of AFP in HepaRG cells pretreated without or with BAPTA-AM (2.5 µM) under RFC or not. Mean ± SD by ANOVA. E The western blot analysis for protein content of AFP in HepaRG cells pretreated without or with BAPTA-AM (2.5 µM) under RFC or not. Mean ± SD by ANOVA. F The effects of YM201636 on calcium flux in HepaRG cells under RFC (10 rpm/min) for 72 h. Mean ± SD by Student’s t-test. G, H The mRNA and protein levels of VAC14 in HepaRG cells were incubated without or with RFC (10 rpm/min) for 72 h as assessed by RT-qPCR assay and immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD by ANOVA. I The RT-qPCR analysis for mRNA level of AFP in HepaRG cells pretreated without or with YM201636 (1 µM) under RFC or not. Mean ± SD by Student’s t-test. J The immunofluorescence staining of AFP in HepaRG cells pretreated without or with YM201636 (1 µM) under RFC conditions or not. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD by ANOVA. K The western blot analysis of AFP content in HepaRG cells pretreated without or with YM201636 (1 µM), under RFC or not. The data are based on three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

PI(3,5)P2 is the best-known direct regulator for the activation of TRPML1 and is mainly synthesized by FIG4, PIKfyve, and VAC1432. Thus, the YM201636, the inhibitor of PI (3,5) P2 was added to detect whether PI(3,5)P2 is involved in simulated microgravity-induced TRPML1 activation. As shown in Fig. 4F, calcium flux was significantly reduced following the application of YM201636. In addition, the mRNA and protein expression levels of VAC14 were also upregulated in the presence of simulated microgravity (Fig. 4G, H), suggesting that PI (3,5) P2 is indeed the activator for TRPML1 under simulated microgravity conditions.

Furthermore, YM201636 pretreatment could also effectively reduce the mRNA and protein levels of AFP triggered by simulated microgravity (Fig. 4I–K). Taken together, these results demonstrated that simulated microgravity-induced differentiation was attributed to lysosomal calcium flux caused by TRPML1 activation.

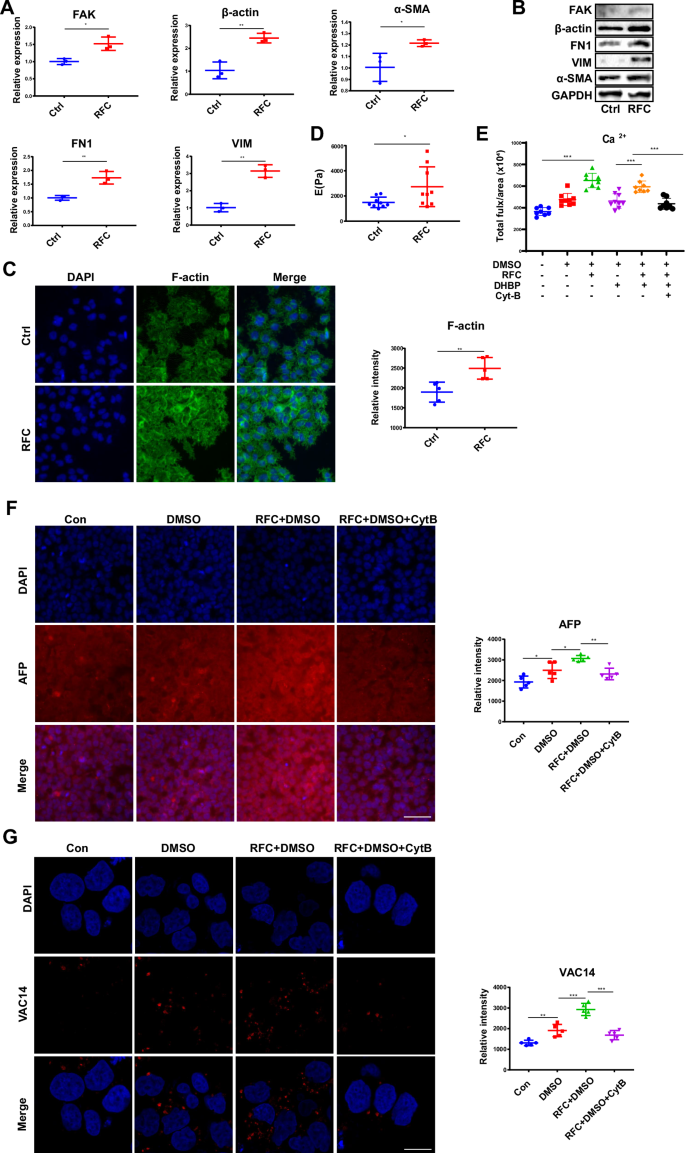

Simulated microgravity affects cell differentiation by remodeling the cytoskeleton

Given that cytoskeletal remodeling contributes a lot to the cells responding to external mechanical signals into internal responses33, thus, the role of the cytoskeleton was evaluated in the effect of simulated microgravity on HepaRG cell differentiation. As a result, the mRNA and protein expression levels of FAK, β-actin, FN1, VIM, and α-SMA were all increased under RFC treatment (Fig. 5A, B). Moreover, the fluorescence intensity of F-actin detected by immunofluorescence was also increased with simulated microgravity effects (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, AFM results showed that simulated microgravity treatment increased HepaRG cells’ stiffness (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these results indicated that simulated microgravity effects could increase the contents of cytoskeleton proteins and the stiffness of cells.

A The RT-qPCR analysis for the mRNA levels of FAK, β-actin, FN1, VIM, and α-SAM in HepaRG cells, without or with RFC. Mean ± SD (n = 3) by Student’s t-test. B The western blot analysis for the protein expression of FAK, β-actin, FN1, VIM, and α-SAM in HepaRG cells, without or with RFC. C Immunofluorescence staining of F-action (green) and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells incubated without or with RFC (10 rpm/min) for 72 h as assessed by confocal imaging. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD by Student’s t-test. D The AFM analysis for the stiffness of HepaRG cells, without or with RFC. Mean ± SD (n = 5) by Student’s t-test. E The effects of cytoskeletal remodeling on calcium flux in HepaRG cells treated without or with RFC (10 rpm/min) for 72 h. Mean ± SD by Student’s t-test. F The content of AFP in HepaRG cells incubated without or with Cyt B, under RFC conditions or not, as assessed by immunofluorescence staining (Con: the undifferentiated group, the other groups: differentiated with DMSO). Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD by ANOVA. G The content of VAC14 in HepaRG cells incubated without or with Cyt B, under RFC conditions or not, as assessed by immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar: 20 μm. Mean ± SD by ANOVA. The data are based on three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The effect of the cytoskeleton on calcium flux in the presence of simulated microgravity effects was further monitored. As shown in Fig. 5E, Cytochalasin B (Cyt B), which was used to destabilize the actin cytoskeleton by altering the polymerization kinetics of actin filaments34, could significantly disrupt simulated microgravity effects -triggered calcium flux. In addition, the protein level of AFP (detected by immunofluorescence) and the activation of TRPML1 (indicated by the upregulation of VAC14) were all markedly decreased upon pretreated with Cyt B in the presence of simulated microgravity effects (Fig. 5F, G).

Previous studies have shown that YAP is known to be regulated by the conformation and tension of the F-actin cytoskeleton and plays a critical role in transducing mechanics signaling35. Therefore, it is inferred that simulated microgravity effects might regulate TRPML1 activity through the YAP-VAC14 pathway. As shown in Fig. S3A, B, simulated microgravity effects promoted the translocation of YAP into the nucleus meanwhile increasing the expression levels of the CYR61 and CTGF, which are downstream targets of YAP. In addition, YAP-TEAD-IN-1 TFA, a competitive peptide inhibitor of YAP-TEAD interaction in the nuclear36, was used, to observe the role of YAP in regulating simulated microgravity-induced VAC14 expression. As shown in Fig. S3C, YAP activity inhibition significantly reduced the protein level of VAC14 under microgravity conditions compared to that under normal gravity conditions, indicating that YAP acts as a critical linkage between simulated microgravity-induced mechanics signaling and TRPML1 activation. Collectively, these results suggested that microgravity-induced cytoskeletal remodeling induced the activation of YAP-PI (3,5) P2-TRPML1 pathway, which subsequently affected calcium flux and cell differentiation when under simulated microgravity conditions.

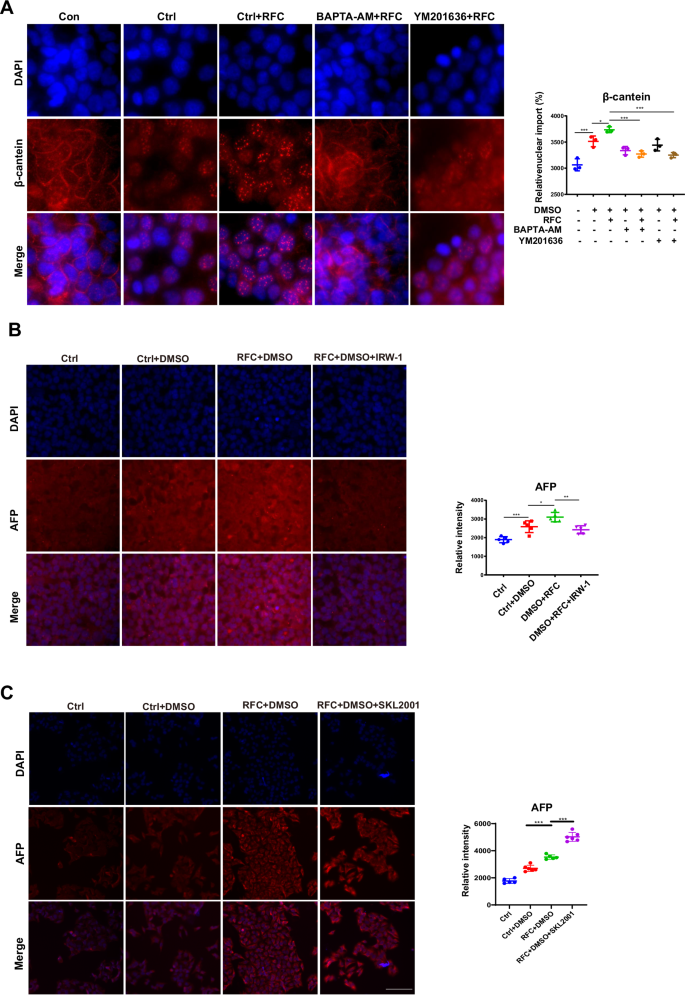

Simulated microgravity promotes cell differentiation through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

In order to elaborate on the cellular mechanism whereby HepaRG differentiation resulted from the release of calcium flux, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which was reported to be downstream of calcium signaling and plays a critical role in stem cell differentiation, was our focus37. As shown in Fig. 6A, β-catenin nuclear import was increased upon RFC treatment; meanwhile, this tendency was successfully inhibited when cells were pre-added with BAPTA-AM and YM201636, indicating that PI(3,5)P2-TRPML1-calcium flux pathway is required for β-catenin nuclear translocation in the presence of simulated microgravity effects. In addition, IWR-1, which is a tankyrase inhibitor of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, could markedly inhibit simulated microgravity-induced AFP protein expression (Fig. 6B), in addition, as reported in previous literature, SKL2001 activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by disrupting the Axin/β-catenin interaction38. Figure 6C showed that simulated microgravity effects enhanced the protein expression of AFP, which could be further enhanced by SKL2001. Taken together, β-catenin nuclear import is one critical step for promoting HepaRG differentiation under simulated microgravity effects conditions.

A The relative nuclear import of β-catenin (red) and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells pre-incubated with BAPTA-AM, and YM201636, under RFC or not, as assessed by immunofluorescence staining (Con: the undifferentiated group, the other groups: differentiated with DMSO). Scale bar: 40 μm. Mean ± SD by ANOVA. B Immunofluorescence staining of AFP (red) and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells pre-incubated with IWR-1 under RFC conditions or not, as assessed by confocal imaging. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD by ANOVA. The data are based on three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. C Immunofluorescence staining and quantification of AFP (red) and DAPI (blue) in HepaRG cells pre-incubated with or without SKL2001(an activator of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, MCE, HY-101085, 20 μM) under normal gravity or cAGO, as assessed by confocal imaging. Scale bar: 80 μm. Mean ± SD by ANOVA. The data are based on three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01.

Discussion

Although the effect of simulated microgravity on cell differentiation is still under debate, our study showed that the differentiation of HepaRG cells could be accelerated by simulated microgravity effects created by RFC/RPM in vivo. Clinostat devices have been widely utilized in microgravity-related biological studies. For example, RPM(random positioning machine, a type of two-axis clinostat device) was used to study the simulated microgravity effects that drive cell proliferation, survival, cell death, cancer stemness, and metastasis in human MDA-MB-231 cells39; exposure to RPM altered the mineralization process and PTX3 expression in SAOS-2 cells to improve cell mineralizing competence40. The liver plays an indispensable role in maintaining overall health and well-being, encompassing metabolism, detoxification, protein synthesis, nutrient storage, immune support, and more41. HepaRG cells are a human liver cell line that can differentiate into well-differentiated hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs) and biliary epithelial cells9. The cell model was widely used in liver function and drug metabolism research, and it has high reproducibility and maintains relatively stable primary human hepatocyte characteristics during long-term culture42. Therefore, HepaRG cells were used to substitute human hepatic stem cells to observe the effect of simulated microgravity effects on cell differentiation. Studies have shown that the addition of DMSO for 3 days could upregulate PXR and PPARα to drive the differentiation of HepaRG cells toward liver-like cells43; HepaRG cells exposed to 2% DMSO for 15 days exhibit mature liver functions to test metabolism44; HepaRG cells were differentiated into hepatocyte-like forms via DMSO treatment, making them suitable for in vitro drug metabolism studies over a period of 4 weeks45. Therefore, the 3-day period of DMSO treatment was chosen, with high efficiency noted in previous studies, to induce the initiation phase of HepaRG cell differentiation into hepatocyte-like cells in the study. Because hepatic cell differentiation biomarkers such as ALB, APF, and CK18 were expressed as earlier as 3 days in HepaRG cells, thus, this time point was used to observe the pro-differentiation effect of simulated microgravity effects, meanwhile avoiding the potential damage caused by RFC for cultured cells in a longer time. It was reported that microgravity and other mechanical stimuli affect the process of cell differentiation. For example, RPM conditions led to the upregulation of genes associated with tumorigenesis during the later stages and accelerated the differentiation or maturation of adipogenic differentiation46; the expression of a robust extracellular matrix mediated by β-TCP scaffolds provides a stiffened microenvironment to accelerate the differentiation of hESC-derived neural crest stem cells and osteoprogenitor cells47; softer materials steer VPCs more rapidly towards an EC-like fate compared to stiffer materials48. All proved that simulated microgravity effects may accelerate the differentiation or maturation of liver-like cells rather than increase the proportion of positive cells. The results that HepaRG cell differentiation can be regulated by altered gravity orientation facilitate a deep understanding of cellular microgravity effects.

Our results showed that simulated microgravity effects led to TRPML1 activation and lysosomal Ca2+ release. TRPML1 is allosterically activated by conformational changes without affecting its mRNA and protein expression levels. Studies have reported that TRPML1 is a Ca2+-releasing cation channel, and its activity can be allosterically regulated by a variety of ligands, such as PI (3,5) P2 and Tisirolimus, whose regulatory pattern is also commonly observed in other ion channels49. For example, Piezo1 and Piezo2 are mechanically activated ion channels that control gating allosterically50; MscL can open its macropore in response to membrane tension51; TREKs and TRAAKs can switch between ‘down’ and ‘up’ states to control their activation52. TRPML1 releases Ca2+ and plays a critical role in mediating lysosome calcium signaling and homeostasis53. It was reported that the lysosomal Ca2+ from TRPML1 plays an essential role in osteoclast differentiation and mature osteoclast function54; in addition, under complicated and changeable environmental factors, TRPML1 could activate the induction of the transcription factor, TFEB, to mediate transcription programs and cause cell protection measures55. The experimental results and the above reports together suggest a clue that the activation of TRPML1 calcium channels may participate in the gravity-sensing mechanism in hepatocytes. However, whether simulated microgravity-induced TRPML1 activation contributes to other physiological outcomes besides differentiation is still unknown and needs further investigation.

Considering the crucial roles of TRPML1 in lysosomal functions, the Ca2+ flux from lysosomal TRPML1 was our focus. Ca2+ flux plays a vital role in cell signaling, serving as a second messenger in various cellular processes, including muscle contraction, neurotransmitter release, gene expression, and cell proliferation56,57. Ca2+ can bind to proteins, such as calmodulin, to change their conformation and then lead to a specific cellular response58,59. Many studies have identified the Wnt/β-catenin pathway as an important pathway that regulates cell development and growth60,61. Here, the results show that lysosomal Ca2+ accelerated the nuclear import of β-catenin and promoted hepatic differentiation of HepaRG cells. However, the distinct role of lysosomal Ca2+ release in regulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is unclear. It is possible that one binding protein of Ca2+ acts as the bridge to promote the nuclear translocation of β-catenin.

Studies have shown that cells responding to microgravity is a typical mechanobiological process that is highly correlated with cytoskeletal remodeling, including the changes of microtubules and actin filaments (F-actin) and the expression of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins62. The dynamic change of actin is closely related to cell differentiation and proliferation. For example, a slightly disordered and less rigid actin cytoskeleton is an essential feature for the differentiation of adipocytes from MSCs63; the interaction between actin cytoskeleton and adhesion promotes the regulation of chondrocyte differentiation64. In differentiation studies, shear stress-mediated differentiation was found to lead to increased expression of cytoskeletal intermediate filaments in mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs)65. Here, the results show that the expression levels of the cytoskeleton and ECM proteins were upregulated during cell differentiation under simulated microgravity conditions, and cytoskeleton remodeling promoted YAP nuclear translocation to regulate the expression of VAC14, which led to TRPML1 activation. The results are consistent with previous reports that the cytoskeleton can facilitate transcription factors to import into the nucleus. For example, microgravity regulates YAP/TAZ activation by disrupting these pathways through cytoskeletal remodeling or nuclear deformation, which then disrupts liver homeostasis66; mechanical stress that transports MKL1 from the nucleus to actin monomers in the binding cytoplasm appears to remove the restriction of PPARg-promoting adipocyte lineage commitment67. When cells are grown on a stiff matrix, the cell adhesion complex and actin cytoskeleton become mechanically coupled, facilitating the translocation of YAP and TAZ into the nucleus68,69. Actin cytoskeleton directly controls cell shape and causes SMYD3 nuclear accumulation70. Additionally, the cytoskeleton regulates transcription factors in MPC differentiation71. Altered cytoskeletal dynamics affect T-box transcription factors into the nucleus in NK Cell72. Lactic acid promotes cytoskeletal remodeling, causing beta-catenin to diffuse from the cell plasma membrane into the nucleus73.

Responses