Ultrafast simultaneous manipulation of multiple ferroic orders through nonlinear phonon excitation

Introduction

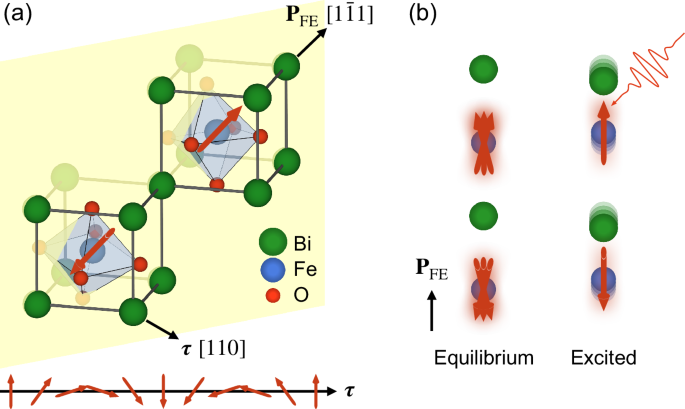

Identifying efficient pathways to control the quantum phases of matter is a key challenge for the development of new materials with functional properties. In magnetoelectric multiferroics, the coupled magnetic and ferroelectric orders enable the control of magnetization using electric fields and vice versa, promising energy-efficient switching operations for data processing. Significant research efforts have been made to develop this concept within the last decade1,2. BiFeO3, shown in Fig. 1a, is a well-known multiferroic material at room temperature, whose ferroelectric polarization can be switched by an applied electric field, which is accompanied by a reorientation of its antiferromagnetic domain3,4. While this magnetoelectric coupling is appealing for low-energy consumption spintronics5,6, the timescale of the switching process is limited by the ramp-up time of the applied electromagnetic fields, generally to nanosecond timescales.

a Rhombohedral crystal structure of BiFeO3 (space group R3c), in which the ferroelectric polarization (PFE) is along the stretched body-diagonal of the pseudocubic unit cell, identified as ([1bar{1}1]) here. The spins between nearest-neighbor iron ions are antiferromagnetically aligned (red arrows) and form a spin cycloid with a wavelength of 62 nm along the normal vector τ of the mirror plane (yellow)25,38. In a single-magnetic domain crystal, the spin cycloid breaks the three-fold rotation symmetry around PFE. b (Left) Initial state with the equilibrium ferroelectric polarization and a thermal broadening of the iron-spin orientation. (Right) The lattice distortion following the resonant excitation of a A1 phonon leads to a change in polarization and to a stabilized orientation of the iron spins.

In contrast, ultrashort laser pulses provide the possibility to generate large electric field strengths on sub-picosecond timescales. Recent experimental realizations of intense terahertz (THz) and mid-infrared (MIR) pulses with peak electric fields exceeding several megavolts per centimeter (MV cm−1) have opened up new pathways for dynamical materials engineering7,8. When the electric field component of a laser pulse is coupled resonantly to the dipole moment of an optical phonon mode, coherent lattice vibrations can be driven with amplitudes exceeding the harmonic regime, making anharmonic contributions of the interatomic potential-energy surface integral parts of the dynamics. A particular manifestation of this anharmonicitiy is nonlinear phononic rectification, a lattice analog to optical rectification, in which nonlinear coupling between phonon modes leads to a quasistatic distortion of the crystal structure9,10,11,12, creating transient crystal geometries that are not accessible in equilibrium. Examples of nonlinear phononic rectification have achieved to manipulate and induce ferroelectric13,14,15,16,17 and magnetic order18,19,20,21,22,23,24 individually. It has so far remained unexplored however, whether light can manipulate multiple ferroic order parameters simultaneously in a single domain.

Here, we coherently excite a high-frequency fully-symmetric (A1) phonon mode in BiFeO3 with intense MIR pulses and we probe the evolution of ferroelectricity and antiferromagnetism using time-resolved second-harmonic generation (SHG) at room temperature. We find that both the ferroelectric and antiferromagnetic contributions to the SHG signal are enhanced on a sub-picosecond timescale. We perform phonon dynamics simulations supported by density functional theory calculations that predict a rectification of the A1 modes arising from both three-phonon coupling and cubic anharmonicities, whose polar atomic displacements increase the magnitude of the ferroelectric contribution to the second-order nonlinear susceptibility tensor. Comparison with experimental data confirms that the total change in SHG signal contains a significant proportion of antiferromagnetic contribution. Our calculations indicate that the rectified displacements along the A1 modes lead to an enhancement of the exchange interaction between the iron spins, which we interpret as a stabilization of the antiferromagnetic state (Fig. 1(b)).

Results

Phonon-driven enhancement of second-harmonic generation

We study a single-crystal sample of BiFeO3, cut and polished along the pseudocubic (110) plane. The ferroelectric polarization PFE is oriented along the body diagonal, [1(bar{1})1], which is parallel to the polished surface, as illustrated in Fig. 1(a). Previous works show that the lattice, electronic, and magnetic degrees of freedom in BiFeO3 are highly sensitive to external fields25,26,27,28,29,30. The large optical nonlinearities in BiFeO331 enables optical rectification that leads to coherent THz emission, which is a sensitive probe of the ferroelectric polarization32. We observed a pronounced angular dependence of the emitted THz field amplitude that verifies that our sample is predominantly in a single domain (Supplementary Note 1).

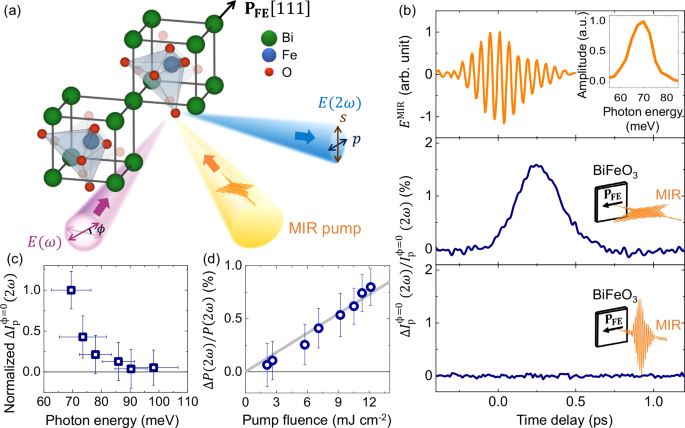

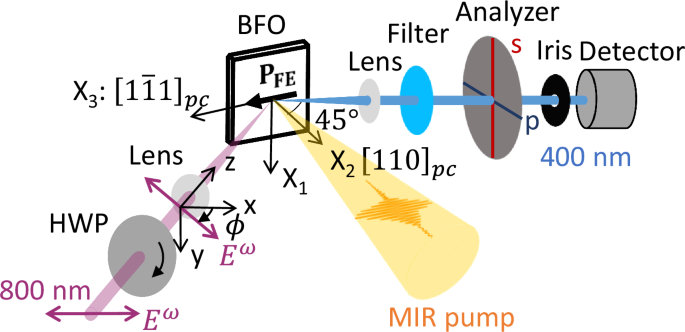

To control structural parameters critical to the ferroic properties, we used intense MIR pulses to excite the high-frequency A1 mode in BiFeO3 at 15.7 THz33. We used frequency-tunable MIR pulses with an excitation fluence of 12 mJ cm−2 to couple to the electric dipole moment of the A1 mode that is oriented along the ferroelectric polarization direction. Time-resolved SHG was used to probe the MIR-induced changes in the ferroic order parameters. The SHG intensity is proportional to the square of the light-induced nonlinear polarization, I(2ω) ∝ ∣P(2ω)∣2. The transient state is characterized by the light-induced change in SHG intensity, ΔI(2ω), with the probe polarization oriented parallel to the light scattering plane (angle ϕ = 0°) and the p-polarization detection configuration. A schematic of the pump-probe geometry is shown in Fig. 2a, indicating the atomic displacements induced by the high-frequency A1 mode that is primarily composed of oxygen-ion motion. In Fig. 2b, we show the characterization of the MIR pump pulse and the polarization dependence of ΔI(2ω). When the polarization of the MIR pulse is oriented along PFE, the SHG intensity is enhanced by 1.5%, whereas a polarization of the MIR pulse perpendicular to PFE yields no pump-induced change. When tuning the center frequency of the MIR pump pulse away from the A1 phonon frequency, the pump-induced ΔI(2ω) decays rapidly, as shown in Fig. 2c, indicating a resonant phonon-driven effect. Furthermore, the maximum transient change in polarization scales linearly with the pump fluence, shown in Fig. 2d, indicating a mechanism based on nonlinear phononic rectification and ionic Raman scattering34.

a We used MIR pulses with a center frequency of 16.9 THz (69 meV) to drive the high-frequency A1 phonon in BiFeO3 at normal incidence. A probe beam at 800 nm was used for SHG with a 45° incidence in reflection geometry. b (Top panel) Electric field component of the MIR pump and Fourier spectrum (inset). (Middle panel) The MIR pump induces a 1.5% transient enhancement of the SHG intensity when polarized along PFE. (Bottom panel) Rotating the MIR pump polarization by 90° results in no pump-probe signal. c Dependence of the SHG signal on the center frequency of the MIR pump pulse. The signal becomes nonzero as the frequency of the pump pulse approaches that of the high-frequency A1 mode, indicating a phonon-driven mechanism. Vertical error bars represent the standard deviation. Horizontal bars are the bandwidths of the mid-infrared pump pulses. d Linear dependence of the light-induced change in second-harmonic polarization on the pump fluence, consistent with nonlinear phononic rectification and ionic Raman scattering34. Vertical error bars represent the standard deviation.

SHG is a sensitive probe for ferroelectricity and magnetic ordering, as the symmetry of the material is reflected by the coefficients of the SHG susceptibility tensor that is given by

where E(ω) is the electric field component of the laser pulse and χ(i) and χ(c) respectively are the ferroelectric and magnetic contributions to the SHG susceptibility tensor35,36,37. The nonzero elements of the SHG tensors are determined by the point-group symmetry of the crystal. At room temperature, the crystal lattice of BiFeO3 is rhombohedral with a 3m point-group symmetry (space group R3c). In the bulk, the antiferromagnetically aligned spins exhibit an additional long-range cycloidal modulation (Fig. 1a) that can be oriented along three equivalent wave vectors, commonly denoted by (τ1, τ2, τ3). The wave vectors τi are perpendicular to PFE25,38. Our sample is predominantly in a single ferroelectric domain, as well as a single spin-cycloid domain, as discussed in Supplementary Notes 1 and 3. The uniqueness of the spin-cycloid wave vector lifts the three-fold rotation symmetry around PFE, and effectively lowers the symmetry of the system to monoclinic, described by point group m. Because the ferroelectric and magnetic properties determine the point-group symmetry, information about them is intrinsically encoded in the symmetry and magnitude of the SHG tensor components that can be probed by varying the polarization of the probe beam.

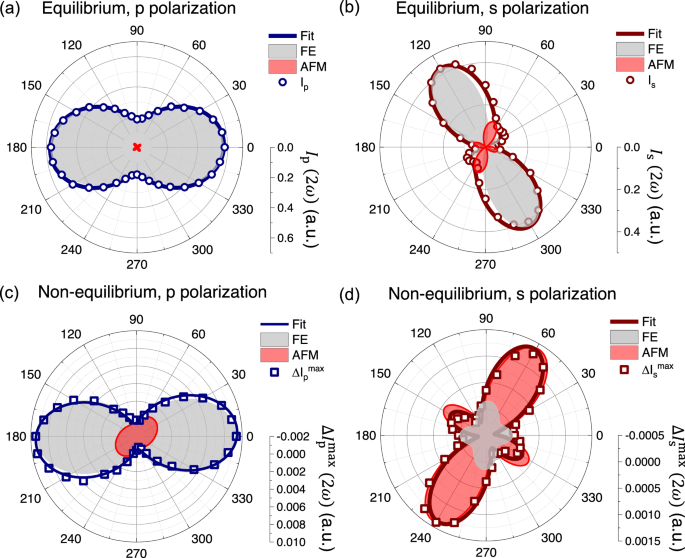

In Fig. 3a, b, we show the probe-polarization dependence of the SHG signal in equilibrium. For the p-polarization detection, the SHG polar plot has two lobes at 0° and 180°, respectively. This can be fit using nearly exclusively the χ(i) tensor components (ferroelectric contribution, grey area). For the s-polarization detection, the SHG signal has four lobes, with a clear asymmetry along the 60° and 240° directions. This asymmetry is due to the nonzero χ(c) tensor components (antiferromagnetic contribution, red area) arising from the symmetry lowering in the single spin-cycloid domain. Similar features were observed in BiFeO3 thin films, in which the orientation of the asymmetric SHG component was used to identify different antiferromagnetic domains39. In Fig. 3c, d, we show the SHG polar plots in the phonon-driven state at the maximum of the pump-probe response. For both the p– and s-polarization detections, (Delta {I}^{max }) is anisotropic and primarily positive with varying probe polarization. The maximum enhancement for both (Delta {I}_{{rm{p}}}^{max }/{I}_{{rm{p}}}) and (Delta {I}_{{rm{s}}}^{max }/{I}_{{rm{s}}}) is approximately (1.5 ± 0.4)%. Intriguingly, the dominant contributions to the pump-induced p– and s-signal changes are from different χ tensors. In the p-detection channel, the maximum enhancement in SHG intensity is along 0° and 180°, given by the ferroelectric SHG tensor (grey area in Fig. 3c). In contrast, in the s-detection channel, the maximum enhancement in SHG intensity is along 60° and 240°, dominated by the antiferromagnetic SHG tensor (red area in Fig. 3d). In order to shed light on the physical mechanisms that lead to this simultaneous enhancement of ferroelectric and antiferromagnetic SHG enhancement, we perform simulations of the nonlinear phonon dynamics that follow the coherent excitation of the high-frequency A1 mode by the MIR pulse.

Polar plots of the equilibrium SHG intensity, I, are shown for (a) p-polarization detection and (b) s-polarization detection (open circles). Polar plots of the pump-induced change of the SHG intensity, ΔI, are shown for (c) p-polarization detection and (d) s-polarization detection at the maximum of the pump-probe response (open squares). In all plots, solid lines are fits of the SHG intensities, composed of the ferroelectric contribution (grey areas) and the antiferromagnetic contribution (red areas). Both the ferroelectric and antiferromagnetic contributions show an enhancement following the resonant phonon excitation.

Simulations of nonlinear phonon dynamics

We evaluate the nonlinear vibrational response and the corresponding dynamics of the lattice polarization and the magnetic interactions in a semi-classical oscillator model, for which we compute the input parameters from first principles using density functional theory. The noncentrosymmetric point-group symmetry of BiFeO3 allows for quadratic-linear three-phonon couplings of the resonantly driven high-frequency A1 mode (calculated eigenfrequency 15.3 THz) to the three low-frequency A1 modes (calculated eigenfrequencies 8.8, 7.4, and 4.8 THz) present in the system, which we denote as ({A}_{1}^{h}) and ({A}_{1}^{l}) in the following. The coupling is described by an interaction potential of (V=c{Q}_{{A}_{1}^{h}}^{2}{Q}_{{A}_{1}^{l}}), where Q is the phonon amplitude and c the coupling coefficient, and can be utilized for nonlinear phononic rectification: when the ({A}_{1}^{h}) mode is coherently driven, it enacts a unidirectional force on the ({A}_{1}^{l}) modes. This force induces a quasistatic displacement of the atoms along the eigenvectors of the ({A}_{1}^{l}) modes that is proportional to the mean-squared amplitude of the ({A}_{1}^{h}) mode, (langle {Q}_{{A}_{1}^{l}}rangle propto langle {Q}_{{A}_{1}^{h}}^{2}rangle). Because the ({A}_{1}^{h}) mode is driven linearly by the electric field component of the pump, ({Q}_{{A}_{1}^{h}} sim E), phononic rectification is quadratic in the pump field and therefore linear in the pump fluence. Furthermore, as the high-frequeny A1 mode is driven with a large amplitude, it can experience self-rectification through cubic-order anharmonicity, described by the potential term (V=tilde{c}{Q}_{{A}_{1}^{h}}^{3}). Because all A1 modes are infrared active, the rectification induces a quasistatic electric dipole moment and therefore an electric polarization in addition to the ferroelectric polarization. Details of the evolution of the phonon amplitudes according to the oscillator model and the density functional theory calculations of the coupling coefficients are provided in the Materials and Methods and in the Supplementary Note 4.

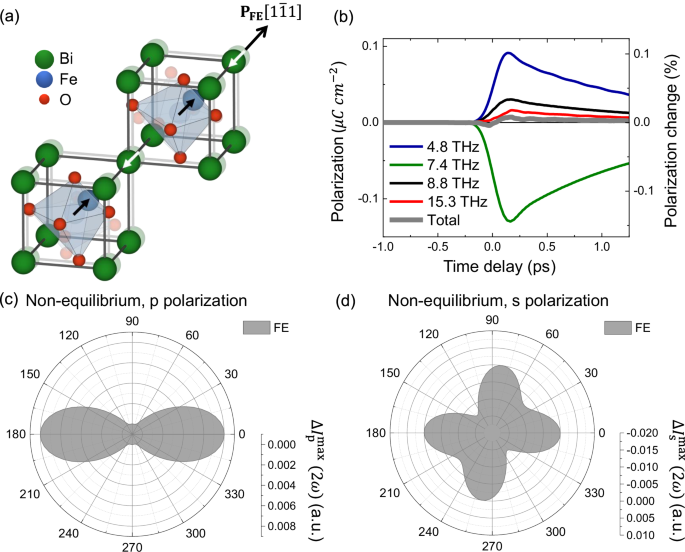

In Fig. 4a, we show the displacements of the ions for the sum of the rectified components of all four A1 modes. The cations, bismuth and iron, move in opposite directions along the [1(bar{1})1] direction. In Fig. 4b, we show the transient polarization induced by the rectified components of all four A1 modes, as well as the relative change of lattice polarization compared to the equilibrium ferroelectric polarization of 90 μC cm−2. The rectifications of the individual A1 modes induce opposing polarizations due to the opposite signs of their mode effective charges that lead to only a small net change in polarization, which can be explained by the opposite net motion of cations shown in Fig. 4a.

a Transient displacements of the ions along the rectified components of all four A1 modes. Displacements are exaggerated for clarity. Besides the change in the oxygen octahedron, the two cations, bismuth and iron, move in opposite directions along the [1(bar{1})1] direction, marked by black and white arrows. b Individual Polarization induced by the rectified components of the four A1 modes. The left axis shows the polarization values, whereas the right axis shows percentile change of the electric polarization with respect to the equilibrium value (90 μC cm−2). Calculated pump-induced changes in the SHG signal for the ferroelectric contribution are shown for p-polarization detection (c) and s-polarization detection (d) at the maximum response of the phonon amplitudes. The shape of the polar plot in p– and s-polarization reproduces the experimental data. While the computations accurately replicate the experimental magnitudes for p-polarization, there is a slight overestimation for s-polarization.

In order to predict the pump-induced change in SHG intensity, we calculate and compare the ferroelectric contribution to the SHG tensor components of both the equilibrium and transiently distorted lattice structures at the maximum of the vibrational response. In Fig. 4c, d, we show the polar plots of the change in SHG intensity, ΔI, for the p– and s-detection channels that we obtain from the modified SHG tensor components due to nonlinear phononic rectification. The calculations well reproduce the experimental features (grey areas in Fig. 3c, d), which confirms the ferroelectric contribution to the SHG enhancement of ΔIp, and supports the experimental finding that the enhancement of ΔIs along 60° and 240° must stem from the antiferromagnetic χ(c) tensor (red area in Fig. 3d).

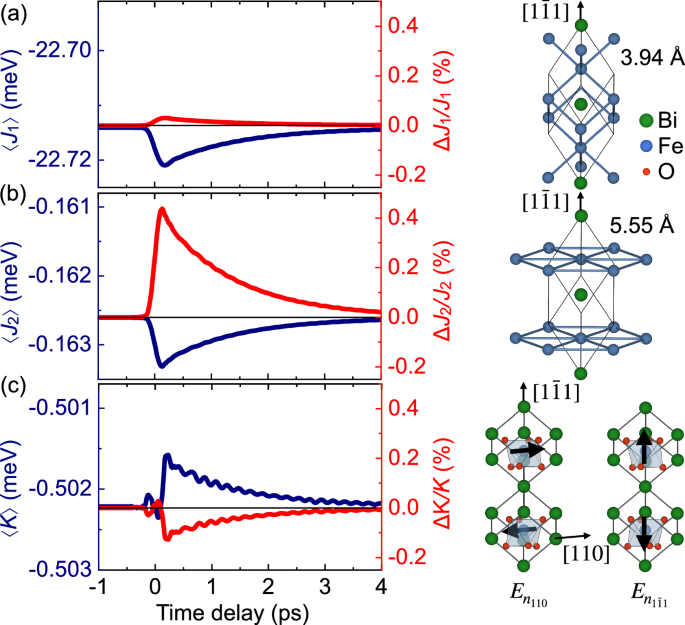

Finally, we investigate the impact of the driven structural state on the magnetic order by computing the changes in the exchange interactions and magnetocrystalline anisotropy of the iron spins that arise from the quasistatic displacements of the A1 modes. We show the time evolution of the mean values of the magnetic interactions in Fig. 5. Intriguingly, we obtain a net enhancement of the magnetic interactions in the driven state, similar to the changes in electric polarization. At the maximum rectified amplitude of the lattice (Supplementary Note 4 Fig. S4), we find that the nearest neighbor exchange (Fig. 5a) increases in magnitude by ∣ΔJ1∣ = 7 μeV or 0.03% and the next nearest neighbor exchange (Fig. 5b) increases by ∣ΔJ2∣ = 0.7 μeV or 0.4%, whereas the magnetocrystalline anisotropy (Fig. 5c) decreases by ∣ΔK∣ = 0.6 μeV or 0.1%. The net change of J1 is an order of magnitude larger than the changes of J2 and K. While the overall net changes are small, they indicate a trend towards a more robust magnetic ordering, consistent with the enhanced antiferromagnetic SHG signal that we measure. Note however that we employed a simplified model, neglecting the spin spiral in the magnetic order of BiFeO3 that requires further terms in the spin Hamiltonian, such as the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Consequently, these numbers should be used with caution and more comprehensive first-principles studies will be necessary in the future to discuss the quantitative relation between the modifications of the magnetic interactions and the antiferromagnetic SHG signal, which are beyond our current methodology.

a Time evolution of the absolute (blue) and relative (red) mean value of the nearest neighbor (NN) exchange interaction 〈J1〉. On the right, we show the bonds corresponding to J1, as well as the distance between the atoms. b Time evolution of the mean next nearest neighbor (NNN) exchange interaction 〈J2〉, with corresponding bonds and atomic distances displayed on the right. c Time evolution of the mean magnetocrystalline anisotropy (MCA) 〈K〉. On the right, we show the spin configurations along the [110] and [1(bar{1})1] directions in the crystal that were used for the computation of the MCA.

Discussion

We have demonstrated a simultaneous enhancement of ferroelectric and antiferromagnetic second-harmonic generation in BiFeO3 by resonant excitation of a high-frequency fully-symmetric phonon mode. We stress that the pump-induced SHG intensity changes are not a multi-domain effect, as the single-crystal sample studied here is predominantly in a single ferroelectric and spin-cycloid domain. The SHG signals from minor domains are negligible and do not match the experimental data, see Supplementary Note 3. We can further exclude the contribution from MIR-induced SHG, which involves the third-order susceptibility tensor, χ(3), in the form given by40,41

The χ(3) signal is spectrally filtered (see Materials and Methods) and the χ(3) process is spatially separated from the χ(2) process due to the 45° angle between the SHG probe and the MIR pump beams. In addition, the χ(3) process would result in a linear pump field dependence for ΔP(2ω), corresponding to a square-root dependence on the pump fluence. However, we observe a linear pump fluence dependence (Fig. 2d).

The enhancement of the ferroelectric contribution can be well reproduced by our calculations of the χ(i) tensor-component modulations due to the transient lattice distortion induced by nonlinear phononic rectification. Intriguingly, the lattice polarizations of the A1 phonon have opposite signs due to the counter-phase motion of the cations along the direction of ferroelectric polarization, PFE, and nearly cancel each other out. In turn, they enhance the SHG tensor components directly, therefore leading to a larger P(2ω) in comparison to the equilibrium state that our measurements pick up. While our theory captures the ferroelectric SHG features well, a direct calculation of the antiferromagnetic SHG tensor is beyond the scope of this work. Our calculations indicate however an overall trend towards enhanced exchange interactions by the rectified displacements of the A1 modes. This mechanism of magnetic-interaction control through phonons has been shown for nonpolar magnets before18,19,20,42. We expect this modification to lead to a more robust magnetic ordering and to changes of the antiferromagnetic χ(c) tensor components, consistent with our experimental findings. The fully-symmetric A1 modes by definition preserve the symmetry of the system and while they leave the relative distances between the iron ions mostly unchanged, they modify the relative distances between the iron and oxygen ions. This could further affect the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction that is responsible for the noncollinear arrangement of spins in BiFeO3. Therefore, more comprehensive first-principles studies clarifying the quantitative relation between the modifications of the magnetic interactions and the antiferromagnetic SHG signal are required in the future.

Finally, we briefly touch on other possible mechanisms of phonon-induced magnetization control, which could be at play in addition to the enhancement of the exchange interaction. One possibility concerns phonon-induced symmetry breaking of the orbital configuration, which has recently been shown to stabilize magnetization above the ordering temperature in a transition-metal ferromagnet43. Due to the fully-symmetric nature of the A1 modes, we can likely rule out this mechanism in our case. Another possibility concerns coherent magnon excitation through coupling to the phonons, which has in the past been described as ionic Raman scattering by magnons44,45,46. While ionic Raman scattering of the A1 modes by the magnons might be possible in BiFeO3, only circularly polarized phonons would lead to a unidirectional force on the spins47. All A1 modes involved in the dynamics are linearly polarized, and we therefore also rule out this mechanism for our case. Furthermore, the spectrum of our MIR pulse is far away from the electromagnon resonances in BiFeO348,49, which allows us to exclude a coupling to the spins through the dipole moment of the spin cycloid. With the data and calculations given thus far, we, therefore, find it most likely that the pronounced enhancement of the nearest neighbor exchange interaction leads to a stabilization of the antiferromagnetic order and to a change of the χ(c) components.

To conclude, our results show that ultrashort pulses in the THz and MIR spectral range can be used to address multiple ferroic order parameters at once, utilizing the coupling to nonlinearly driven phonon modes. We have demonstrated simultaneous ferroelectric and antiferromagnetic SHG enhancement for the case of the prototypical multiferroic material BiFeO3. Our first-principles calculations confirm that the increased ferroelectric SHG signal arises from phonon-mediated increases of the ferroelectric χ(2) tensor. They further indicate an enhancement of the nearest neighbor exchange interaction, consistent with our finding of increased antiferromagnetic SHG. We expect that this approach will be applicable generically to materials exhibiting magnetoelectric coupling. The ferroic orders in BiFeO3 form independently below the respective Curie and Néel temperatures at 1100 and 640 K and are only weakly coupled. In contrast, the ferroic orders are interdependent and emerge together in so-called type-II multiferroics, but these materials often suffer from very low multiferroic ordering temperatures50. An intriguing question to address in the future therefore concerns whether both ferroic orders can be stabilized simultaneously above the multiferroic ordering temperature through coherent phonon excitation, for example through an enhancement of the magnetoelectric coupling between the two ferroic orders. This problem can be regarded in the same broad context as the light-induced stabilization of superconductivity, ferroelectricity, and magnetism demonstrated in recent experiments15,16,43,51,52.

Materials and methods

Crystal growth

The BiFeO3 single crystal was grown using a traveling solvent technique in a Laser Floating Zone (LFZ) furnace53. Bi2O3 (99.975%, Alfa Aesar) and Fe2O3 (99.995%, Alfa Aesar) powder are mixed in molar ratio 1:1 and 4:1 for the feed rod and the traveling solvent, respectively. The feed rod material was sintered at 800 °C for 20 h with one intermediated grinding, and the solvent was sintered at 700 °C for 5 h. A 0.15 g solvent pellet was placed on top of the seed rod before starting the floating zone growth. The growth was performed in air, and the growth rate was 1 mm h−1. The as-grown crystal is oriented by a Laue X-ray camera. The ferroelectric domain structure has been characterized by optical microscope, circular interference differential contrast, and piezoresponse force microscopy imaging (Supplementary Note 3).

MIR pump-SHG probe setup

The fundamental beam for SHG is from a Ti:sapphire laser with a repetition rate of 1 kHz, energy of 30 nJ, and a duration of 40 fs. A schematic representation of the setup is shown in Fig. 6. A half-wave plate (HWP) was used to rotate the polarization of the fundamental beam. The beam was focused to 120 micron in diameter on the sample. The SHG signal was spectrally filtered by a band-pass filter (with a 400 nm center frequency and a 10 nm FWHM bandwidth), spatially filtered by an iris, and then detected by a photo-multiplier tube. The spectral and spatial filtering processes eliminate the detection of the MIR-induced SHG40,41. A Glan-Taylor prism was used to select the desired polarization of the second-harmonic signal. All optical measurements were performed at room temperature, with a 45° incidence in reflection geometry.

A half-wave plate (HWP) rotates the polarization of the 800 nm pulses. A dichroic mirror (not shown) reflects the second-harmonic generation signal and removes the residual 800 nm signal. A band-pass filter (10 nm bandwidth) removes signals from higher-order optical processes. An analyzer selects either the vertically polarized (s) or horizontally polarized (p) SHG signal.

MIR pump pulses with tunable wavelengths between 13 and 18.5 microns, and a duration of 250 fs were generated by optical parametric amplification and subsequent difference frequency generation in a GaSe crystal. The MIR pulses were focused on to the sample at normal incidence, with a diameter of 220 microns and a maximum excitation fluence of 12 mJ cm−2.

Fits of the SHG signal

At room temperature, BiFeO3 crystallizes in rhombohedral symmetry with point group 3m and space group R3c. We set X3 as the ferroelectric axis and X2 as the normal to the mirror plane of the trigonal structure (Fig. 6). In a single antiferromagnetic domain, the long-range cycloidal modulation of the spin breaks the three-fold rotation symmetry around PFE, reducing the symmetry of the material to monoclinic with point group m. Details of the SHG tensors can be found in Supplementary Note 2. The fit reveals that the cycloidal spin modulation direction is along X2.

Theory of nonlinear phonon dynamics

We use a phenomenological oscillator model to evaluate the nonlinear vibrational response of the A1 modes and the corresponding lattice-polarization dynamics following the excitation by an ultrashort MIR pulse, for which we compute all parameters from first principles using density functional theory. Specifically, we solve the equations of motion

where Qi are the normal mode coordinates (amplitudes) and κi the phenomenological linewidths of the A1 modes in BiFeO3, i ∈ {A1}. V = V0 + Vint is the potential energy, consisting of an equilibrium potential, V0, and an interaction potential, Vint. We expand V0 up to fourth order in anharmonic and nonlinear coupling terms,

where Ωi is the phonon eigenfrequency, and cijk and dijkl are the anharmonic and nonlinear coupling coefficients. Because the A1 modes are fully symmetric, all permutations of modes are allowed by symmetry in the anharmonic terms. We take into account all single-mode anharmonicities (ciii, diiii), but only nonlinear couplings of the high-frequency A1(15.3 THz) mode, which is resonantly driven, to the other A1 modes of the system. See Supplementary Note 4 for the density functional theory calculations of the coupling coefficients.

The interaction potential, Vint, contains the coupling of the electric dipole moment of the infrared-active phonon A1 modes, pi, to the electric field component of the laser pulse, E(t), and can be written as

where the linear polarization of the laser pulse is assumed to be aligned along the ferroelectric polarization direction of the crystal. Qi is the phonon amplitude as evaluated in Eq. (2) and Zi is the mode effective charge given by ({Z}_{i}={sum }_{n}{Z}_{n}^{* }{q}_{n,i}/sqrt{{M}_{n}}). ({Z}_{n}^{* }) is the Born effective charge tensor, qn,i the phonon eigenvector, and Mn the ionic mass of ion n, and the index n runs over all ions in the unit cell. We model the electric field component of the laser pulse as (E(t)={E}_{0}exp [-{t}^{2}/(2{({tau }_{0}/sqrt{8ln 2})}^{2})]cos ({omega }_{0}t)) and set its parameters to the experimental values: a full width at half maximum (FWHM) duration of 250 fs, a central frequency of 16.9 THz, and a fluence of 12 mJ cm−2 (peak electric field E0 = 5.3 MV cm−1). Because ω0 is far off resonance from the three low-frequency A1 modes, only the contribution of the A1(15.3 THz) mode plays a role in Eq. (4). Finally, the time-dependent electric polarization, P(t), induced by the displacements of the ions along the coordinates of the infrared-active A1 modes, is given by

where Vc is the volume of the unit cell.

We next compute the phonon-induced modulation of the SHG tensor components. Due to the lack of inversion symmetry in the crystal, any infrared-active mode can linearly modify the components of χ(2) as

Here, ({chi }_{{rm{equilibrium}}}^{(2)}) is the equilibrium second-order susceptibility and ({partial }_{{Q}_{j}}{chi }_{j}^{(2)}) is the phonon-induced change. We compute both the equilibrium and nonequilibrium tensor components for the ferroelectric contribution, χ(i), from first principles, see Supplementary Note 4.

We finally compute the time-dependent modifications of the exchange interactions, J1 and J2, as well as the magnetocrystalline anisotropy, K, as a result of the rectified A1 mode displacements

We calculate ({J}_{1/2}^{{rm{equilibrium}}}), Kequilibrium, ({partial }_{{Q}_{j}}{J}_{1/2}), and ({partial }_{{Q}_{j}}K) from first principles, see Supplementary Note 4. The mean change in magnetic interactions over time is given by their dependence on the rectified phonon coordinate, e.g., 〈K(t)〉 ≡ K[〈Q(t)〉].

Responses