Uniting imagination and evidence by design to navigate climate survival in urbanizing deltas

Delta management in the Netherlands and beyond

A significant portion of the Netherlands is situated in a delta. Much of the land is prone to flooding and about one-quarter is below sea level, resulting in significant challenges with both the sea and the inland rivers that discharge into it. For centuries, thousands of smaller infrastructural works such as dikes, dams and polders were built to provide (amongst others) flood protection. From the 1920s onward, initiated after the devastating Zuiderzee flood of 1916 and the North Sea flood of 1953, this strategy of predominantly locally led, small-scale interventions was replaced by a national program encompassing large-scale delta works to shorten the coastline. The implementation of the Delta Works began promptly after the flood of 1953, with the first project launched in 1954. It took nearly three decades to complete all 13 projects comprising dams, sluices, locks, dikes, and storm surge barriers. The swift start was possible because the design and underlying research had already begun two decades earlier23. Initially, the design and plans for the Delta Works were not conceived as a final solution but rather as a spatial vision for a long-term transformation process allowing the large sea arms to silt up naturally aimed at creating a more natural delta24.

After the wake-up calls of the near-miss Rhine and Meuse floods in 1993 and 1995, the flood protection strategy of the large Dutch rivers shifted from using hard infrastructure to creating more space for rivers through the so-called Room for the River and Meuse Works programs. This approach included strategies such as depoldering, dredging new and deeper channels, and lowering the floodplain. This transition was facilitated by a professional and societal shift in the Netherlands towards “nature-based” water management that started in that same period25. The new approach emphasized working with natural processes to enhance flood protection, restore ecosystems, and improve the overall resilience of the river landscape. The designs that shaped the Room for the River Program were developed and scientifically supported by modelling and prototyping studies, which started already in the 80 s, making them ready for implementation after the near disasters of 1993 and 1995.

The recent unprecedented storms and heavy rain that impacted Western Europe in 2021 and 2023 have demonstrated the effectiveness of these programs in preventing severe coastal and river flooding in the Netherlands. For example, despite the extremely high water levels in the Meuse River near the towns of Itteren and Borgharen in 2021, which corresponded to a return period of approximately 200 years, no flooding occurred. These towns had previously experienced significant flooding in 1993 and 1995, with return periods of approximately 160 and 80 years, respectively, prior to the implementation of the Room for the River program. Notably, the peak discharge in 2021 was higher, further underscoring the program’s effectiveness26.

As concerns regarding the implications of climate change for The Netherlands grew, a new national program known as the Dutch Delta Program was launched in 2010. The program coordinates the water-related challenges of climate-proofing the Netherlands. At the core of the program are three over-arching thematic policy frameworks and coherent sets of measures, known as Delta plans for flood protection, fresh-water availability, and spatial adaptation. The program is evaluated and re-calibrated every six years. This reassessment examines both content and methodology.

The Dutch Delta Program started its operation under the implicit assumption that climate change primarily involved gradual trends that were straightforward to monitor and anticipate following an adaptive delta management approach. The impacts of climate change requiring more radical system interventions were assumed to occur in a later phase, likely after 2050. However, since the launch of this program, extreme rainfall, droughts, and heatwaves are showing that climate change manifests itself in unpredictable weather events with increasing intensity and frequency27. Moreover, the timeframe within which multiple long-term transformative strategies are still realistic options is rapidly narrowing. These observations are now urging an acceleration of the pace of implementation and a change of direction from incremental (adaptive) to transformative delta management of the program28.

The need to shift from incremental (adaptive) to transformative delta management has sparked a renewed focus of the Delta Program on imagination and design to address climate change. Building upon previous experiences both imagination and evidence through spatial visualizations by design are currently used for the scientific exploration of new perspectives on the future of the Dutch delta. The ambition is to create appealing long-term visions on what these futures might look like including the pathways to achieve them. Research institutes, national, regional and local governments, specialised consultancy and engineering bureaus, building and dredging companies, are working together to further develop these long-term solution directions. These outcomes will be used in the upcoming reassessment in 2027 of the Delta Program to review the existing policy frameworks and Delta plans27.

Similar design-driven trajectories have also been followed in recent efforts to future-proofing the Mississippi delta in the post-Hurricane Katrina ‘Dutch Dialogues’ (2008–2014) and the Hudson-Delaware delta in the New York Post-Sandy adaptation plan ‘Rebuild by Design’ supported by The Rockefeller Foundation (2013-ongoing) and the ‘Water as Leverage’ initiative for urban climate resilience of Asian cities. The resulting innovative and creative ways of disaster recovery (‘build back better’), brought hope and inspiration to the local communities and decisionmakers29. In such examples, design complemented the traditional largely science-based approaches with imaginative appeals by conceptualizing and visualizing futures. This involves navigating spatial translations and their consequences, all while reconciling societal beliefs and desires with the innovative spatial concepts being introduced30.

Design is a complex and multi-dimensional field that has numerous meanings. It refers to a process as well as to a product. We define design for urbanized deltas in two ways. First, design is a plan, scheme, or model that highlights new challenges for political and societal debate, creates narratives linking various subproblems, scales, and interests, and guides future directions that give insight in what decisions can be made31. Through imaginative visual communication, it has the power to transcend current limitations or blocked visions of the future, enabling free reasoning about alternative futures. Second, design is the activity, process, or action functioning as a knowledge brokerage instrument, bringing stakeholders together to conceive and create integrative plans for human interventions that shape complex environments through interactions with human and natural processes over time32.

Role of Design for transformative change

What can we learn from these experiences? Five crucial conditions for transformative change appear to be evident in subsequent instances within these national and international programs. These conditions are grounded in the model ‘Five Dimensions of Futures Consciousness’ by Ahvenharju, et al.33. The first condition relates to the strong beliefs of agency. Disasters or the threat of natural hazards, along with opportunities and appealing perspectives, can act as powerful catalysts and tipping points for change. The second condition relates to the time perspective: the existence of a long-term spatial vision that spans decades into the future, appeals to our imagination and is informed by the past and the present, directs and enforces the development of an alternative strategy. The third condition relates to the openness to alternatives. Imagination by design thrived in the pre-disaster era as there was sufficient time for creativity, exploration and investigation, which mutually reinforced each other in a design process. These allowed authorities and experts to leverage a more diverse range of perspectives, opening up the design-driven solution space. As a result, the formulation and implementation of these programs could commence almost immediately after the (almost) disaster occurred. The fourth condition concerns systems perception, focussing on the dominant role of natural processes in design, the holistic integration of nature-based solutions, the acknowledgment of humans as integral components of the natural ecosystem, and the dynamic interplay of these elements within the delta. Lastly, this condition focuses on the ethical and social aspects of futures thinking. Climate change exemplifies the ethical and social dimensions of futures thinking as the effects of present-day activities will profoundly impact future generations. The urgency to make use of what moves people to provoke climate action has become manifest in the Netherlands and in many other deltas. Dutch history has shown that imagination and evidence by design have the power to take professionals, policy and the general public beyond present conditions of life, spatial relations, and contexts required to initiate and direct transformative change for climate proofing the Netherlands.

Elevating imagination

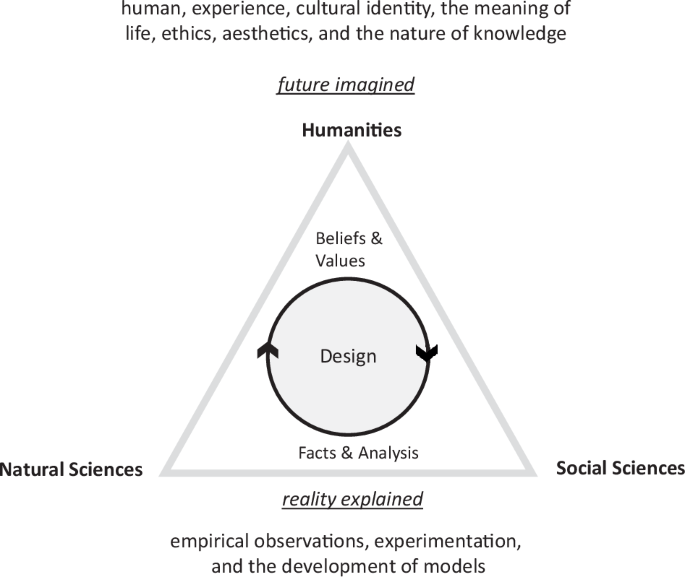

In the end, our ability to endure the challenges of the climate crisis hinges on our capacity to purposefully and consciously cultivate a profound desire for change before the next disaster strikes. We believe that only through the interaction of imagination and evidence creation we will be able to shape, analyze, and effectively communicate appealing futures that drive change. History showed us that design has the ability to inspire human society while advancing scientific theories and models and creating space for engaged professional and civic participation. We plea for a shift in attitude in climate science and delta management, one that elevates imagination by design to an equal level as modelling and analysis of natural and social subsystems of deltas. This requires interdisciplinary approaches uniting the realms of Natural Sciences, Social Sciences and the Humanities (see Fig. 1). Considering past delta system transformations in the Netherlands, we conclude that design may be the key to boundary spanning. Design should therefore be strengthened as a capacity in academics, professional practice, and society at large. In order to do so we need a Delta Program for all our sinking deltas. One that can enable positive tipping points. A program that serves as a catalyst for propositional, creative, iterative, and collaborative thinking to advance and share our understanding of the challenges of sea level rise and other climate-related issues. The Dutch Delta Program may serve as a pioneering example in this direction, having recently initiated concrete steps toward transformative delta management. By organizing hackathons and design workshops that involve a broad range of stakeholders and disciplines, the program aims to imagine, analyze, and communicate desirable and plausible long-term futures and pathways (see example in Fig. 2)28.

They emphasize empirical observation, experimentation, and the development of models. Humanities aim to explore questions about the human experience, cultural identity, the meaning of life, ethics, aesthetics, and the nature of knowledge. The humanities value subjectivity, including imagination. Design brings them together though informed imagination, evidence-based plans and scenarios, and long-term visions. As such design overcomes different viewpoints, while design future-proofs human society and culture while advancing scientific theories and models.

Spatial design of a section of the Dutch delta (Fig. 2a) developed to protect the Port City area of Rotterdam. This will be achieved by rerouting the current flood defense (dike ring 14) and creating a sponge city. The port will continue to be elevated incrementally while simultaneously transitioning to a green economy (see visual representation Fig. 2b). Design was created by Lola, Urbanisten and Royal Haskoning DHV in 2022 as part of the Redesigning Deltas Design Study22. Written permission for its use has been granted.

Responses