Universal in situ supersaturated crystallization enables 3D printable afterglow hydrogel

Introduction

The development of stretchable afterglow materials has emerged as a pivotal advancement in the field of functional materials, effectively merging the mechanical resilience of polymer with the optical properties of afterglow materials. This synergy not only expands the practical applications of afterglow materials but also holds profound implications for various fields, such as wearable electronics, advanced display technologies, and biocompatible devices1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Initially, afterglow materials were confined to rigid15,16,17 and brittle substrates18,19, primarily due to their reliance on rigid crystalline matrices to prevent non-radiative decay processes20. However, recent investigations have overcome these limitations by integrating afterglow capabilities into flexible and stretchable polymers. The polymer matrix not only facilitates certain elongation and recovery but also ensures the preservation of afterglow properties21,22,23. Despite these flourishing developments, the mechanical flexibility and fatigue resistance of polymeric afterglow materials still lag behind conventional stretchable materials, thus limiting their utility in emerging technologies that demand flexibility and durability under physical stress24,25,26,27. Therefore, it is urgent to develop a universal strategy for constructing stretchable afterglow materials with enhanced tensile capacity and elongated lifetime.

Hydrogels, formed through the crosslinking of hydrophilic polymers into 3D network structures, exhibit exceptional mechanical properties of deformability, making them an ideal matrix for developing stretchable organic afterglow materials28,29,30,31. Recently, clusterization-triggered afterglow emission has been achieved from carbonyl cluster in hydrogels due to the inhibition of non-radiative decay of nontraditional luminogens through efficient confinement of molecular motion and segment sliding32,33,34,35. However, achieving ultralong-lived afterglow emission remains a significant challenge due to the disaggregation of nontraditional luminogens induced by the large amount of water in hydrogels36,37. Interestingly, intense and ultralong afterglow emission can be enabled through crystal engineering of traditional luminogens, effectively suppressing non-radiative transitions caused by water and oxygen through effective intermolecular locking38,39,40. Therefore, we envision that the integration of traditional afterglow crystals into stretchable hydrogels could catalyze a transformative shift in the field of stretchable afterglow materials, bridging the gap between optical properties and mechanical flexibility; nonetheless, a general strategy for the introduction of afterglow crystals into the hydrogel has yet to be proposed.

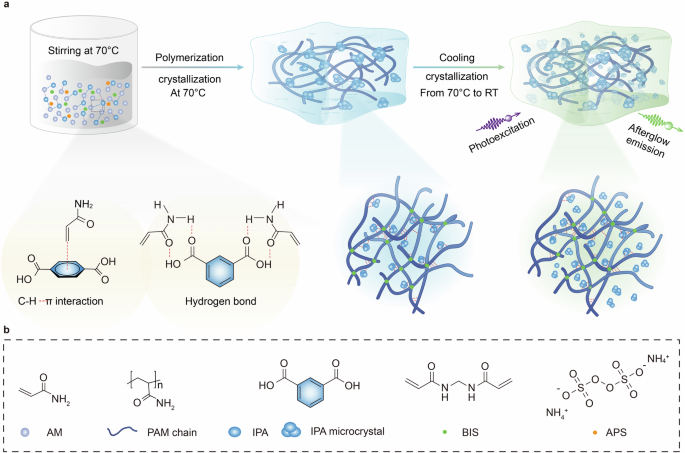

Herein, we present a novel approach utilizing supersaturated crystallization (SC)41,42,43 strategy (Fig. 1) to fabricate afterglow hydrogels. This strategy involves the formation of crystals from a metastable soluble system triggered by external stimulus. As a proof of concept, the typical afterglow crystal of isophthalic acid (IPA)44,45,46 was selected as solute and acrylamide (AM)28,47,48,49,50 monomer as the cosolute because of their strong intermolecular interactions (Fig. 1a, left) to prepare the precursor. Upon polymerization (Fig. 1a, middle) and cooling (Fig. 1a, right), SC processes could be induced from the precursor, resulting in the afterglow hydrogel. The constructed afterglow hydrogel not only exhibits green afterglow emission with extended lifetimes exceeding 600 ms from IPA crystals but also preserves mechanical flexibility, with tensile stress surpassing 398 kPa, elongation exceeding 400%, a high water contents 65.21% and durability of 100 cycles from polyacrylamide (PAM) hydrogel. This demonstrates that the SC strategy imparts the resulting afterglow hydrogel with excellent stretchability and an ultralong lifetime, outperforming the most recently reported afterglow hydrogels (Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, we demonstrate the universality of the SC strategy and establish diverse applications of afterglow hydrogels in anti-counterfeiting encryption. Furthermore, we develop a printable ink suitable for digital light processing (DLP) 3D printing technology. By optimizing printing conditions, we achieve the photo crosslinking and SC processes of the ink during 3D printing. Ultimately, we successfully fabricated a series of intricately structured products with afterglow. This work, purposefully constructing afterglow hydrogels with mechanical and optical performance, provides a promising tactic and platform for the exploration of advanced soft materials.

a With the aid of various interactions between isophthalic acid (IPA) solute and acrylamide (AM) cosolute, a transparent precursor containing supersaturated IPA is achieved at 70 °C; upon the polymerization of PAM hydrogel at 70 °C, the interactions between AM and IPA are destroyed, leading to the in situ microcrystal growth of IPA solute through the SC process; after the polymerization, with further decrease in temperature, the SC process continuous due to the decreased solubility at low temperatures. b Molecule structures of AM, PAM chain, IPA, BIS and APS.

Results

Material design and synthesis

SC process occurs when a soluble system, initially in a metastable state, is triggered by an external event, such as temperature and/or the introduction of an external stimulus. This causes the supersaturated solute to form crystal. This spontaneous precipitation and crystallization process continues until the system reaches equilibrium again. To prepare the afterglow hydrogel, an in situ SC strategy is introduced using the IPA as solute, which exhibits afterglow emissions, and AM as the cosolute, serving as the monomer. Briefly, a transparent precursor AM solution with supersaturated IPA is prepared because of various interactions between IPA and AM. After radical polymerization at 70 °C, the cosolute AM is converted to PAM hydrogel, facilitating the occurrence of SC of IPA due to the disparate solubilities of IPA in AM and PAM (Fig. 2a). With increased polymerization time, the IPA microcrystals within the PAM hydrogel continue to grow. Interestingly, as the temperature gradually decreases to room temperature, the SC of IPA persists due to cooling crystallization (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1) resulting in the formation of the PAM-IPA afterglow hydrogel.

a Polarized optical microscopy (POM) images illustrating the in situ SC process: polymerization crystallization (red arrow, top panel) and cooling crystallization (blue arrow, bottom panel) of PAM-IPA hydrogel (Scale bar = 25 μm). b, c Normalized steady-state photoluminescence (SSPL) and delayed PL (10 ms delay) spectra as well as lifetime decay profiles of PAM-IPA hydrogel, PAM film and IPA crystal excited by 300 nm UV light. d The comparison of lifetime and strain of PAM-IPA hydrogel among the reported pure organic stretchable afterglow hydrogel, the specific reference information can be found in Table S1. e Excitation-delayed PL (10 ms delay) mappings of PAM-IPA hydrogel. f Time-resolved emission spectra (TRES) of PAM-IPA hydrogel excited by 300 nm UV light.

Photophysical properties of afterglow hydrogel

The PAM-IPA hydrogel exhibits blue-violet luminescence upon excitation by 280 nm UV light (Supplementary Fig. 2), displaying fluorescence emission at 360 nm (Fig. 2b) with a nanosecond fluorescence lifetime (Supplementary Fig. 3). Excitingly, intense green afterglow emission persists for over 5 s in the PAM-IPA hydrogel after removal of the excitation source under ambient conditions, as confirmed by delayed photoluminescence (PL) spectra and Commission International de L’Eclairage (CIE) 1931 coordinates (Fig. 2b, c and Supplementary Fig. 4). The delayed PL spectra show a main peak around 500 nm with a lifetime of 695 ms, which is redshifted by approximately 140 nm from the fluorescence, confirming the attainment of afterglow properties in the PAM-IPA hydrogel. The ultralong lifetime of PAM-IPA hydrogel is among the best results in the reported organic stretchable afterglow hydrogels (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 1). The PAM-IPA hydrogel possesses a photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) of 2.58% (Supplementary Table 2). Additionally, the fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 3) and afterglow lifetimes (Fig. 2c) of PAM-IPA hydrogel are higher than those of the PAM film but lower than those of the IPA crystals due to the combined effects of the destruction of bulk IPA crystals and the stabilization of PAM through hydrogen interactions between IPA and PAM.

To ascertain the origin of the luminescence source in the PAM-IPA hydrogel, the photophysical properties of the PAM film and the IPA crystal were investigated. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6, the PAM-IPA hydrogel exhibits excitation dependent SSPL emission from PAM cluster and long-tail emission from IPA crystals. Moreover, both the PAM film and IPA crystal demonstrate afterglow emission peaks at 430 and 470 nm, as well as 380 and 500 nm, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7); these emission peaks align with those observed in the PAM-IPA hydrogel, which suggests that the afterglow emission originates from both the PAM film and IPA crystal (Fig. 2b). This assertion is further supported by absorption and excitation spectra, showing the similar excitation spectra to those of the PAM film and IPA crystals when monitoring the emission peaks at 430 and 500 nm (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9), respectively. Moreover, we observe excitation-dependent afterglow emission (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 4) due to the inherent dual luminescent sources of PAM and IPA.

To explore the impact of the excitation wavelength, temperature, cosolute and solute concentration on afterglow emission in the PAM-IPA hydrogel, we conducted a series of photophysical property measurements. The excitation-delayed PL mapping of the PAM-IPA hydrogel reveals an optimal excitation wavelength of 300 nm (Fig. 2e), indicating stable afterglow emission with increasing delayed time, repeated light excitation, and long-term storage as confirmed by time-resolved emission spectra (Fig. 2f), cycle excited delayed PL intensity spectra (Supplementary Fig. 11) and PL spectra before and after storage (Supplementary Fig. 12). Considering the cost-effectiveness of IPA and AM, good reproducibility (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 13) and long-term stability (Supplementary Fig. 12), this afterglow hydrogel shows great potential application in commercial use. Temperature-dependent delayed PL spectra of the PAM-IPA hydrogel exhibits enhanced luminescent intensities with decreased temperature due to the suppression of the non-radiative decay of triplet excitons. Notably, as the temperature decreased, the main afterglow emission peaks excited by 300 nm UV light shifted from 500 nm of IPA crystal (Supplementary Fig. 14, top) to 430 nm of PAM cluster (Supplementary Fig. 14, middle). This shift could be attributed to the transition from the free water at room temperature to the ice at freezing temperature in the PAM-IPA hydrogel, potentially suppressing the interaction between free water and PAM for the inhibition of free water-induced PAM cluster disruption, thus enabling more PAM cluster and resulting in dominant afterglow emission from PAM at low temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 15). In addition, with increasing concentrations of IPA and/or AM, the PAM-IPA hydrogel demonstrates identical afterglow emissions with improved afterglow lifetimes (Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17).

Mechanism investigation of SC

To unravel the mechanism of in situ microcrystal growth for the development of the afterglow hydrogel, a series of experiments were conducted. As depicted in Supplementary Figs. 18, 19 and Tables S3, S4, the solubility of IPA in aqueous solution is low. In contrast, the solubility is enhanced when AM is used as the cosolute; with an increase in temperature from 25 to 70 °C (Fig. 3a), the improved solubilities of IPA in AM and corresponding PAM aqueous solutions are observed. Furthermore, with a further increase in the molar concentration of AM from 4 M to 6 M, the solubility of IPA is not substantially improved, thus a 4 M AM aqueous solution is selected to prepare the afterglow hydrogel.

a Solubility of IPA in AM aqueous solutions and in corresponding PAM aqueous solutions at 70 °C and 25 °C. b FTIR spectra of AM-IPA and AM solution mixture in ethanol. c 2D NOESY spectrum of AM and IPA with molar ratio of 1:1 in dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 ranging from 5 to 9 ppm. d, e Differential scanning calorimetry thermograms curves (d) and fractions of free water and bound water (e) during the heating process from −50 to 30 °C. Heating rate, 5 °C/min. f Theoretically calculated binding energies of two adjacent molecules for AM-IPA, PAM-IPA (5 repeat units), and PAM-IPA (10 repeat units). g X-ray diffraction spectra of the IPA crystal, PAM-IPA hydrogel and PAM hydrogel. h SEM images of the PAM-IPA hydrogel (Scale bar = 20 μm). i POM images of microcrystals in the PAM-IPA hydrogel. The left shows the cross section of hydrogel (Scale bar = 200 μm). j Micro-Raman spectra of IPA crystal and PAM-IPA hydrogel. Spot a is located at the IPA microcrystal of PAM-IPA hydrogel. The light spot detection area is 2.08 μm2.

To further demonstrate the critical role of AM cosolute in enhancing the solubility of IPA in aqueous solutions, the Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and 2D nuclear overhauser effect spectroscopy (2D NOESY) (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 20) spectra were carried out. Compared to the AM solution, the vibrational peaks corresponding to the carbonyl and amino groups in the AM-IPA solution show a redshift of 8 and 6 cm−1, respectively (Fig. 3b), which confirms the hydrogen interaction between AM and IPA. The correlated signals observed in the 2D NOESY spectra (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 20) suggest the existence of C − H···π interactions between protons on the phenyl group of IPA and protons on the ethylene group of AM35,51,52. These interactions empower the increased solubility of IPA in AM aqueous solution.

Notably, compared to the AM aqueous solutions, the solubility of IPA is noticeably decreased in the corresponding PAM aqueous solutions (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Figs. 21 and 22) owing to the dominant entropy effect on the solute partition according to Flory-Huggins theory53,54. Additionally, after polymerization of AM, the fraction of free water is decreased due to the interaction between PAM and water. As calculated by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, Fig. 3d, e and Supplementary Fig. 23), the fraction of free water slightly decreases from 83.44% in AM solution to 50.13% in PAM hydrogel and 53.33% in PAM-IPA hydrogel. Moreover, the theoretically calculated binding energies (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 24) gradually decrease from 33.9 kJ/mol to 17.11 kJ/mol with an increase in PAM polymerization degree from AM-IPA to PAM-IPA (5 repeat AM units) and to PAM-IPA (10 repeat AM units)35. Through the combined effect of decreased free water and reduced binding energy, the solubility of IPA indeed decreases in the hydrogel, playing a key role in achieving the SC process for in situ microcrystal growth when AM is converted to PAM hydrogel, thereby enabling the construction of PAM-IPA afterglow hydrogel. The IPA microcrystals in PAM-IPA afterglow hydrogel can be confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Fig. 3g) showing featured diffraction peaks that correspond to IPA. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis displays embedded IPA microcrystals in the 3D network structure of hydrogel (Fig. 3h) as further verified by POM images (Fig. 3i and Supplementary Fig. 25) exhibiting the typical birefringence of crystals and Raman spectra demonstrating characteristic vibration signals from IPA (Fig. 3j and Supplementary Fig. 26).

Mechanical and afterglow properties analyses

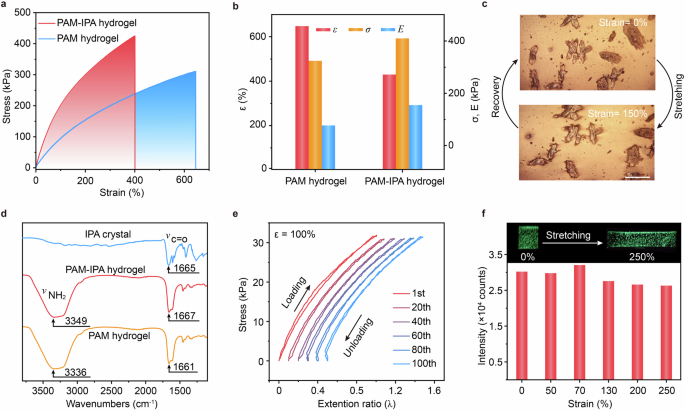

The PAM-IPA hydrogel demonstrates an increase in stress from 311 kPa to 398 kPa and Young’s modulus from 62 kPa to 142 kPa (Fig. 4a, b) compared to the undoped PAM hydrogel, indicating improved tensile strength55. Both stress and Young’s modulus continue to rise with increasing IPA concentrations in the PAM-IPA hydrogel (Supplementary Fig. 27) due to the IPA microcrystals serving as stress dissipation centers (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 28). The slightly decreased stretchability from 643% to 400% may be attributed to the introduction of IPA microcrystals disrupts the hydrogen bond network as demonstrated by the blue shift in the N − H asymmetric vibration peak and C=O vibration peak (Fig. 4d). As shown in Supplementary Figs. 17 and 27, the afterglow properties were largely enhanced when the IPA concentration increases in PAM-IPA hydrogel, but the stretchability was decreased, suggesting the trade-off between stretchability and afterglow properties. Considering both the good stretchability and ultralong lifetime, the optimized doping concentration of IPA should be 1.05 wt.%. Moreover, a lower hysteresis performance is achieved (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 13), with a reduction in the hysteresis loop from the original 3.2% to 1.9% after 100 cycles. The similar rheological properties observed between PAM-IPA and PAM hydrogels (Supplementary Fig. 29) suggest that the incorporation of a small amount of IPA has a limited influence on the formation of stable hydrogel phase. Encouragingly, the afterglow intensities show minimal change during deformation (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 30). Additionally, excellent afterglow emission can be maintained when the PAM-IPA hydrogel is stretched in water (Supplementary Fig. 31) since the swelling property of the hydrogel has limited effect on the optical properties of IPA microcrystals owing to its high water content of 65.21% (Supplementary Fig. 32). This combined investigation demonstrates that the PAM-IPA afterglow hydrogel exhibits efficient elasticity, fatigue resistance and afterglow performance under varied external stimuli, laying the foundation for its practical applications.

a, b Stress-strain curves and corresponding stress, strain and Young’s modulus of PAM-IPA hydrogel and PAM hydrogel. c POM images of the PAM-IPA hydrogel at the original and stretching states. (Scale bar = 200 μm) d FTIR spectra of IPA crystal, PAM-IPA hydrogel and PAM hydrogel. e Stretch-recovery curves of the PAM-IPA hydrogel at a strain of 100% after 100 cycles. Horizontally shifted curves represent the 1st, 20th, 40th, 60th, 80th and 100th cycles. f Afterglow intensity of PAM-IPA hydrogels at strains of 0%, 50%, 70%, 130%, 200%, and 250%. Inset (top) shows the afterglow photographs of the PAM-IPA hydrogel at a strain of 250%.

Universality of SC strategy

To demonstrate the universality of the SC strategy in the in situ microcrystal growth process for fabricating mechanically flexible afterglow hydrogels, two widely investigated afterglow crystals, terephthalic acid (TPA)46 and 1,4-benzenediboronic acid (BDA)56, were selected as solutes to construct the corresponding PAM-TPA and PAM-BDA afterglow hydrogels. These hydrogels exhibit efficient afterglow with emission peaks at 515 and 505 nm with lifetimes of 108 and 905 ms (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 33), respectively. SEM images demonstrate the embedded microcrystals in PAM-BDA hydrogel network, showing uniform B element distribution in the microcrystals (Supplementary Fig. 34). Further, the commonly used hydrogel matrices of acrylic acid (AA)57 and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)58 were chosen as cosolutes. Efficient green afterglows are observed in the obtained PAA-IPA and PVA-IPA hydrogels with lifetimes of 142 ms at 484 nm and 364 ms at 489 nm, respectively, under ambient conditions (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. 33). These results underscore the effectiveness of the SC strategy in designing afterglow hydrogels with elongated lifetime and enhanced luminescent intensity.

a, b Normalized delayed PL spectra and lifetime decay profiles of PAM-BDA hydrogel, PAM-TPA hydrogel, PAA-IPA hydrogel and PVA-IPA hydrogel. c, d Schematic preparation procedures of anti-counterfeiting label (c) and QR code (d) and corresponding photographs taken under excitation and after the removal of 280 nm UV light. e, f Schematic overview of the digital light processing (DLP) printing apparatus (e) and materials used in the DLP printing (f). g Photographs of 3D-printed models taken under daylight, excitation and after removal of a 280 nm UV light. (Scale bar = 2 cm).

3D printing and anti-counterfeiting encryption

Benefiting from the mechanical robustness and persistent luminescence characteristics of hydrogels, applications in anti-counterfeiting and three-dimensional (3D) printing applications are explored59,60,61. Initially, a precursor solution of AM and a blue fluorescent (PAMCz)62 dye mixture is poured into the template (Fig. 5c, top left). After polymerization at 70 °C for about 5 min, another precursor comprising AM and IPA is introduced into the template with IAM characters (Fig. 5c, top right), which is then transferred into the oven for polymerization to prepare afterglow hydrogels with anti-counterfeiting label of IAM. Under UV excitation, only blue fluorescence is observed; however, the encrypted message IAM emerges after turning off the UV lamp (Fig. 5c, bottom). The fabricated hydrogel label demonstrates an intrinsic capacity for versatile deformation, validating its applicability on irregular surfaces. Two-dimensional quick response (QR) codes (Fig. 5d) and substantial figurative representations, including ducks and bears (Supplementary Fig. 35), with exceptional afterglow and flexibility, can be facilely fabricated through the template method.

Although significant progress has been made in the development of afterglow hydrogel materials, printing afterglow hydrogel into precisely prescribed 3D geometries remains a challenging task. Utilizing its rapid photopolymerization characteristics, various 3D objects can be facilely fabricated via advanced DLP 3D printing method (Fig. 5f). To enhance the precision of the printing process, an inhibitor was incorporated into the precursor. An assortment of alphabetical characters with exceptionally smooth edges and vertices are printed (Supplementary Fig. 36). Furthermore, the designed 3D structures featuring both stacked layers and intricate hollow elements with high structural recognition ability under and after removal of UV excitation are achieved. These afterglow properties minimize extraneous light interference, accentuating the detailed contours of the models (Fig. 5g). More strikingly, clear outlines of a human ear are achieved in both fluorescence and afterglow models. These results demonstrate the potential of afterglow hydrogels in a wide range of applications through 3D printing techniques.

Discussion

In summary, our study successfully demonstrates the fabrication of afterglow hydrogels through a universal strategy of in situ SC process, leveraging polymerization and temperature-induced solubility disparity. By integrating afterglow moieties into the hydrogel matrix, afterglow performance with a lifetime of 695 ms, alongside inherent flexibility and resilience are simultaneously achieved. Moreover, the fatigue resistance demonstrates effective afterglow and hydrogel stabilities even after undergoing 100 cycles. Furthermore, this strategy is adaptable to systems comprising different hydrogel matrices and luminescent components, enabling the design of a diverse range of hydrogels with tailored afterglow properties. The successful application in 3D printing and anti-counterfeiting further broadens the potential demonstrations of flexible afterglow hydrogels. This work not only provides a valuable design strategy for constructing the afterglow hydrogel with regulated photophysical and mechanical properties but also explores their extensive applications in areas such as biological 3D printing, antibacterial coatings and soft electronics.

Methods

Materials

All reagents and solvents were purchased from Nanjing Chemical Reagent Co. and Energy Chemical. Unless otherwise specified, these reagents and solvents were used without further purification. The purities for all purchased materials are described below: Acrylamide (99%), isophthalic acid (99%), N,N’-methylenebisacrylamide (99%), Ammonium persulfate (98%), acrylic acid (98%), poly(vinyl alcohol) (AR), terephthalic acid (99%), 1,4-phenylenebisboronic acid (98%), lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (95%), tartrazine (97%) was used after three times recrystallization.

Measurements

The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and 2D nuclear overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) spectra were measured on a Bruker Ultra Shield Plus 400 MHz NMR instrument using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the reference standard and methyl deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6) as solvents. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) was measured on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer with Cu Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å) radiation. Photographs were taken with a Canon EOS 80D camera. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was carried out on a Bruker alpha instrument with 35 scans and a resolution of 2 cm−1. Polarizing optical microscope (POM) images were performed on C16 camera and OLYMPUS BX43F. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was carried out on a Hitach S-4800 instrument and SEM-EDX was carried out on EX-250. Micro-Raman spectra were carried out on a Renishaw in Via (UK) Laser Microscopic Confocal Raman Spectrometer equipped with a 532 nm diode laser source. Ultraviolet/Visible (UV/Vis) absorption spectra were characterized on a Jasco V-750 spectrophotometer. Steady-state photoluminescence (SSPL) spectra, delayed PL spectra (delay time 10 ms), fluorescence/afterglow lifetime decay curves, and time-resolved emission spectra (TRES) were conducted on an Edinburgh FLS980 and FLS1000 spectrometer. For the fluorescence lifetime test, a picosecond pulsed laser (EPLED-295, wavelength: 295 nm, pulse width: 833.7 ps) was used; the absolute photoluminescence quantum efficiency (PLQY) was performed on the Edinburgh FLS980 instruments equipped with an integrating sphere, and the wavelength-dependent sensitivity of the detector has been calibrated automatically by Edinburgh instruments during PLQY measurement. Thermal gravimetric analyzer (TGA) test was taken on a STA2500 (TA Instruments) with a heating rate of 5 °C/min. Differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) analysis was performed on the NETZSCH DSC214 instrument with a heating/cooling rate of 5 °C/min. The enthalpy of freezing water and melting of ice in the sample cell followed by the peak integration of the DSC curve. For the melting enthalpy of ice in solution and hydrogel, the samples went through a heating-cooling-heating cycle to eliminate the thermal potential, data in the second heating process was used for integral calculation. Tensile measurements were performed with a stretch rate of 100 mm/min on a commercial tensile tester (CMT7504). Rheological behaviors were analyzed by a DHR-2 (TA Instruments). Strain sweeps were implemented from 0.01% to 10% at a frequency of 1 Hz. Frequency sweeps were recorded in a linear region at 25 °C in a frequency range of 0.1–100 rad/s with a strain amplitude of 0.1%. Temperature sweeps were performed in a temperature range of 20-80 °C with a heating rate of 5 °C/min.

Preparation of PAM-IPA Hydrogel

The isophthalic acid doped polyacrylamide (PAM-IPA) hydrogel with different compositions was prepared by free radical polymerization. Prescribed amounts of IPA (0-1.05 wt.% compared to the AM), AM (4 M), and methylene-bis-acrylamide (BIS) (0.2%) were dissolved in water (5 mL) to obtain a transparent precursor solution, which was kept at 70 °C for 2 h to ensure IPA totally dissolved. Then, a prescribed amount of ammonium persulfate (APS) (1 M) was dissolved in 100 μL of water and added to the precursor solution at approximately 35 °C. The mixture was immediately injected into a reaction cell consisting of a pair of glass substrates and 2 mm-thick silicon spacers, which was kept in an oven at 70 °C for 1 h and kept in ambient conditions for 12 h to complete the reaction and to produce PAM-IPA hydrogel. The isophthalic acid doped poly(acrylic acid) (PAA-IPA) hydrogel, isophthalic acid doped poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA-IPA) hydrogel, terephthalic acid (TPA) doped polyacrylamide (PAM-TPA) hydrogel and 1,4-phenylenebisboronic acid (BDA) doped polyacrylamide (PAM-BDA) hydrogel were obtained by a similar protocol.

Theoretical calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) was used to optimize ground-state (S0) structures under M062X/TZVP level. Vibrational frequency calculations were also performed to verify the minimum nature of the optimized structures. Time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) calculations were carried out to obtain the binding energies under M062X/TZVP level based on optimized S0 structures.

3D ink preparation and 3D printing

IPA (1.05 wt.%), AM (4 M), BIS (0.2%), lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (1 mg) and tartrazine (0.5 wt.%) were dissolved in water (5 mL) to obtain a transparent precursor solution, which was kept at 70 °C for 2 h to ensure IPA totally dissolved. Wherein tartrazine is an inhibitor of polymerization to guaranteed printing accuracy. Then, the mixture was transferred to the oven after printing is completed.

A top-down digital light processing printer assembled using an electric motor and a commercial projector (EFL8601P) was employed for hydrogel printing. The DLP printing system operates with a 365 nm LED light source. The printing process was performed with a 100 μm layer thickness, separation velocity of 25 mm/min, a slider velocity of 100 mm/min, the ink tank temperature of 30 °C, the building platform temperature of 25 °C and a 6 s wait time after each step. The light intensity was set at 3 mW/cm2 and the irradiation time was set as 6 s for the bottom three layers (close to the building platform) and 3.5 s for all upper layers. After printing, 3D objects were kept in an oven at 70 °C for 1 h and kept in ambient conditions for 12 h to obtain 3D printed afterglow hydrogel samples.

Responses